Health Education Initiatives for People Who Have Experienced Prison: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

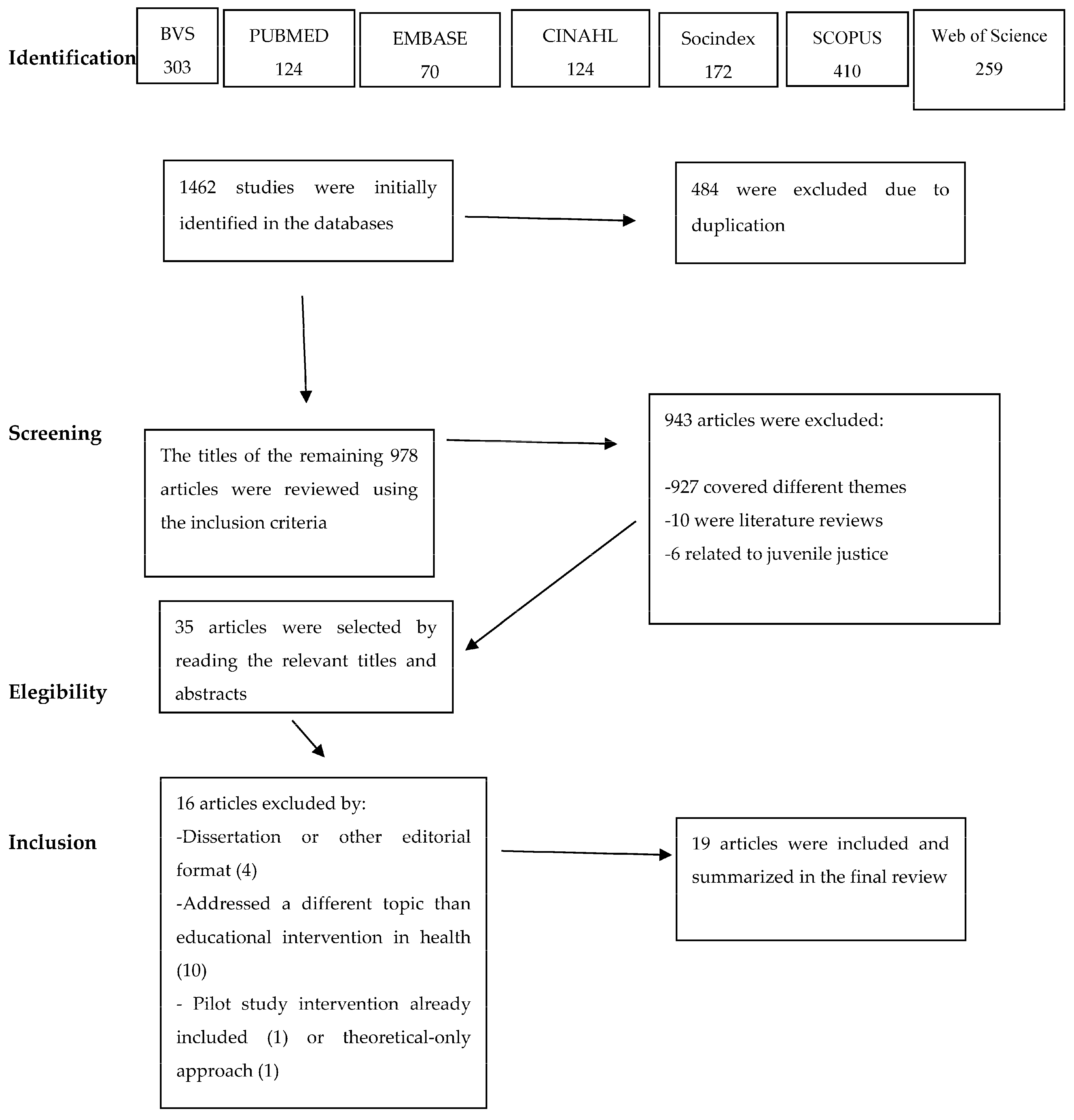

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Studies Characterization

| Authors, Year, and Place of Study | Theme and Moment of Intervention | Study Objectives | Methods | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hunt et al. (2022, EUA) [18] | Women’s health; moment of intervention: transition to the community | To develop a sustainable pre-release education program to reduce the risk of opioid overdose post-release in female inmates in a rural county jail. | Qualitative study The authors developed a re-entry program entitled Healthy Outcomes Post Release Education (HOPE), using the Roy adaptation model as a theoretical framework. | The implementation of a successful re-entry program for the vulnerable female incarcerated population has the potential to reduce the risk of opioid overdose death and negative health outcomes post-release and provide an opportunity for adapting culture and starting other supportive re-entry type programs. |

| Geana et al. (2021, EUA) [29] | Women’s health; moment of intervention: after release | Enhance health literacy through the development and testing of an intervention (mHealth). | Mixed study. A website was developed for the intervention based on four themes identified in previous research (cervical cancer, breast health, reproductive health, and STIs). | This intervention may increase the health literacy of women participating in the study and may have positive health and behavioral effects. |

| Winkelman et al. (2021, EUA) [31] | Alcohol, opioids, and other substances; moment of intervention: transition to the community and after release | To examine the acceptability, feasibility, and preliminary clinical outcomes of a smoking cessation intervention for individuals who are incarcerated. | Randomized clinical trial. Two groups: (a) Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT): received 1 h of smoking cessation counseling in jail, a supply of nicotine lozenges upon release, and up to 4 telephone counseling sessions after release; (b) brief health education (BHE): received 30 min of general health education in jail. | Initiation of counseling plus NRT during incarceration and continuing after release is feasible and acceptable to participants and may be associated with reduced cigarette use after release. Participants expressed a positive impression of the in-jail counseling or education. |

| Banta-Green et al. (2020, EUA) [32] | Alcohol, opioids, and other substances; moment of intervention: transition to the community and after release | To evaluate an opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment decision-making intervention to determine whether the intervention increased medications for opioid use (MOUD) disorder initiation post-release. | Observational retrospective cohort study. The intervention: (a) included education on OUD/MOUD; (b) explored people’s perceptions and history of use of MOUD; (c) provided a motivational-interviewing-informed approach to evaluating the pros and cons of each medication, given a person’s preferences and life circumstances; and (d) helped identify specific next steps towards initiating MOUD, if selected as the desired treatment. | Those who received the intervention were significantly more likely to start medication during the first month after release from prison but not in the following months. The short-term nature of the effect observed in this study supports efforts to determine how to support people in staying on medications for opioid use disorder as long as they wish to continue. |

| Brousseau et al. (2020, EUA) [19] | Women’s health; moment of intervention: transition to the community | To assess the efficacy of motivational interviewing as an individualized intervention to increase the initiation of contraceptive methods while incarcerated and continuation after release in female inmates. | Randomized control trial (RCT). Treatment group: women assigned to motivational interviewing. Control group: women assigned educational videos with counseling. | There was higher initiation of contraception in the motivational interviewing group compared to educational video group. After controlling for significant treatment group differences, motivational interviewing did not increase contraceptive initiation, nor did it decrease pregnancies. |

| Wiersema et al. (2019, EUA) [33] | HIV and other sexually transmitted infections Moment of intervention: transition to the community and after release | Describe the adaptation of an evidence-based intervention to influence sexual behavior. | Quantitative study. The risk reduction intervention delivered through two 1.5 h sessions. Participants completed a baseline survey before the first group session and a postintervention survey a few days after the last group session. The baseline survey contained questions to assess HIV knowledge, HIV risk, and health-promoting behaviors. | Participants showed significantly improved knowledge of HIV. 90 days after release from prison, participants reported improved “CLEAR thinking”, reduced risk behaviors, and improved health-promoting behaviors. |

| Corsino et al. (2018, Brazil) [20] | Women’s health; moment of intervention: transition to the community | To analyze the impact of educational action on HPV carried out with women in prison in Mato Grosso. | Experimental, inferential comparative study of the “before and after” type. | Carrying out the educational action contributed significantly to the information the women had about HPV. Educational actions are efficient forms of information that equip women in decision making. There is a clear need for educational interventions in prisons to promote health and prevent disease, which can reduce the vulnerability of individuals. |

| Staton et al. (2018, EUA) [34] | Women’s health; moment of intervention: transition to the community and after release | Examine the delivery of an HIV risk reduction intervention focused on prevention education (NIDA Standard) and an enhanced individualized risk reduction intervention (MI-HIV) in rural prisons to reach high-risk rural women who use drugs. Specifically, the study examines short-term outcomes 3 months after release from prison for high-risk rural women. | Quantitative study. Consultative sampling, screening, and face-to-face interview approach to recruiting hard-to-reach, out-of-treatment rural drug-using women in three Appalachian-area prisons. Analyses included descriptive statistics, multinomial logistic regression, and stepwise regression to identify significant correlates of recent and past injecting drug use compared to never injecting. | HIV education interventions can be associated with risk-reduction behaviors. Decreases in HIV risk behaviors were observed at follow-up across all conditions. Although participants in the MI-HIV group experienced reductions in outcomes compared to the NIDA Standard group, these estimates did not reach significance. Educational interventions about HIV can be associated with risk reduction behaviors. |

| Thornton et al. (2018, EUA) [21] | HIV and other sexually transmitted infections; moment of intervention: transition to the community | Evaluate the ECHO New Mexico Peer Education Project, focusing on the short-term impact of training. | Mixed study. Intensive 40 h training (delivered over five consecutive days) for incarcerated people. Ten-hour workshop, conducted for 2 to 3.5 h over 3 to 5 days. Peer educators conduct the training in its entirety, and students receive short educational presentations and are engaged in a variety of learning activities. Three-hour educational session at the prison’s central reception for all men entering the prison system. | Significant changes were observed in knowledge, attitudes, behavioral intention, and self-efficacy. Programs like this have the potential to help slow a deadly HIV epidemic by educating individuals to reduce the risk of acquisition and transmission, both in prison and upon return to their communities. |

| Williams et al. (2018, EUA) [30] | HIV and other sexually transmitted infections; moment of intervention: after release | To determine the efficacy of the cognitive-behavioral intervention in improving the sexual health of minority men after jail release. | Randomized controlled trial. Participants were assessed and tested for three sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and HIV at baseline and 3 months post-intervention and followed up for 3 more months. | The intervention group’s STD risk knowledge, partner communication about condoms, and condom application skills improved. A tailored risk reduction intervention for men with infection histories can affect sexual risk behaviors. |

| Hernandez et al. (2016, Cuba) [22] | HIV and other sexually transmitted infections; moment of intervention: transition to the community | To perform an educational intervention study in Mar Verde Penitentiary Center with the purpose of diminishing syphilis incidence. | Qualitative study. The educational work was based on a methodological manual for training prosecutors who work with their peers in prisons modified by the authors for the prevention of STIs/HIV/AIDS. The promoters carried out a set of prevention activities, such as video debates, face-to-face conversations and counseling, knowledge meetings, conferences, and get-togethers. | With the educational intervention, it was possible to reverse the epidemiological situation of syphilis, since in 7 days, 42 promoters were trained who worked with their peers and who, with support, were able to develop an educational program that, in less than 2 years, reduced the incidence of infection by 70.6%. It is recommended to promote the implementation of educational interventions in other penal institutions for their usefulness in the improvement of the health of its inmates and as an important contribution to the system of medical care in these centers. |

| Fogel et al. (2015, EUA) [35] | Women’s health; moment of intervention: transition to the community and after release | To test the efficacy of an adapted evidence-based HIV–sexually transmitted infection (STI) behavioral intervention (Providing Opportunities for Women’s Empowerment, Risk-Reduction, and Relationships, or POWER) among incarcerated women. | Randomized trial intervention participants attended 8 POWER sessions; control participants received a single standard-of-care STI prevention session. Participants were followed up at 3 and 6 months after release. The intervention efficacy was examined with mixed-effects models. | Women were followed up 3 and 6 months after release. There were decreases in HIV risk behaviors and intention to begin treatment, but the differences between the groups were not statistically significant. A multi-session HIV-STI prevention intervention adapted for and delivered to women in prison can significantly reduce sexual risk behaviors and increase protective behaviors after re-entry into the community. Prisons provide an opportunity to deliver behavioral interventions to a population at high risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV and STIs. |

| Sifunda et al. (2008, South Africa) [23] | HIV and sexually transmitted infections; moment of intervention: transition to the community | To test the effectiveness of a systematically developed health education intervention targeting soon-to-be-released prison inmates on psychosocial determinants of reducing risky sexual behaviors. | Nested experimental design. Within each of four selected prisons, there was both a control and an experimental group. The experimental groups were divided between those who were instructed by an HIV-positive peer educator and those who were instructed by an HIV-negative peer educator. The study used a pre-test, a post-test prior to release from prison, and a 3- to 6-month community follow-up test as evaluation measurements for all participating inmates. | This study was one of the few that explored the use of theoretical approaches in designing health education interventions aimed at inmates and probably the only one conducted in sub-Saharan prison conditions. Curriculum content should be simple and targeted at the desired areas of change to ensure that even people with low literacy levels are able to understand all program concepts. The results demonstrate an already established benefit of small group skill-building risk-reduction programs. The lessons learned and the issues that emerged during the adaptation of the intervention underscore the need for linguistically and socioculturally appropriate, locally designed programs that can shed some light and lead to greater understanding of these contextual differences. |

| Valle Yanes et al. (2008, Cuba) [24] | HIV and other sexually transmitted infections; moment of intervention: transition to the community | Evaluate the effectiveness of an educational intervention to raise awareness of HIV. | Quantitative study. A pre-experimental study (before–after) was carried out. Five 45 min meetings were held with each group of 25 prisoners to implement the educational program. Six weeks later, the initial instrument was applied again to verify knowledge acquisition. | Before the educational intervention, 71% of the inmates surveyed had an “unacceptable” level of knowledge, as they did not recognize the three most common ways to prevent infection. After, that number dropped to 53%. After the educational intervention, participants acquired acceptable and moderately acceptable levels of knowledge about HIV in terms of the most common ways to become infected, prevention, and vulnerability to infection. |

| Minc et al. (2007, Austrália) [25] | HIV and other sexually transmitted infections; moment of intervention: transition to the community | To deliver engaging, relevant, and clear health messages to prison inmates, ex-inmates, and families in relation to HIV, hepatitis, and sexual health. | Interventional radio program/qualitative study. A community restorative center that broadcasts a weekly half-hour radio program to prisoners and the community to provide support to prisoners, exprisoners, and their families. | The most popular programs were those that either featured a particular goal or an inmate’s, ex-inmate’s, or family’s lived experience of the prison system rather than programs specifically devoted to health. The vast majority of prisoners and stakeholders consider a radio program for prisoners to be both a relevant and useful strategy to complement existing written health promotion material and address poor literacy levels. |

| White et al. (2003, EUA) [26] | Tuberculosis; moment of intervention: transition to the community | To describe the educational process provided to inmates in jail, including developing the educational protocol, hiring, and training of staff members. To describe the application of an educational intervention in a jail setting. | Qualitative study. Development of the protocol and educational process provided to prisoners. The individual educational session lasted 10 to 15 min and was led by community health workers, who presented themselves as representatives of an external agency (the University). The materials were delivered at the end. | The project was very successful in educating inmates and motivating prisoners to continue care after release. As compared with 3% clinic visit rates before the project began, 24% to 37% of inmates receiving education through the tuberculosis prevention project completed tuberculosis clinic visits depending on intervention arm. Jails provide a rewarding opportunity to work with persons at high risk for a number of diseases. The jail setting is a safe and relatively quiet place and provides an opportunity to educate a population in great need of intervention. |

| Grinstead et al. (2001, EUA) [27] | HIV and other sexually transmitted infections; moment of intervention: transition to the community and after release | Reduce risky sexual and drug-related behavior and encourage the use of community resources following release. | Quantitative study. Eight sessions over two consecutive weeks, totaling 16 to 20 h. During the seventh and eighth sessions, service providers from participating release counties provided information and made appointments for post-release services. | HIV-positive inmates were well informed about the facts of transmission and prevention. Need for transitional case management to facilitate use of community resources, especially drug and alcohol treatment. |

| Crundall and Deacon (1997, Australia) [36] | Alcohol, opioids, and other substances; moment of intervention: transition to the community and after release | Determine the effect of an alcohol education course on alcohol consumption, drinking group, disruptive behavior, criminal activity, family relationships, how they use their time, general health, ability to cope and take responsibility. | Mixed study (quanti-qualitative). Treatment group: those who completed the course. Control group: others who had not done the course. | The prisoners attending the course showed improvements in all dimensions when compared to the control subjects. Involvement in the course influenced more than just the drinking and offending behaviors of the prisoners, with indirect gains in terms of health, personal dispositions, and relationships. |

| El-bassel et al. (1997, EUA) [28] | Women’s health; moment of intervention: transition to the community | Enhance sexual safety and reduce risky behavior. | Mixed study. Pre-intervention: focus groups with 20 women (arrested and released). Intervention: eight weekly 1.5 h sessions included simulations, minimal didactic content, and reading tasks between sessions. During the first two months after release, there were eight “boosting” sessions, the first being four days after release. | By learning about HIV rates among women prisoners, participants gained a better understanding of how HIV affects children, families, and communities. As a result of this knowledge, followed by training to achieve social support, self-efficacy can be enhanced. |

4. Discussion

4.1. Transition from Prison to the Community and Health Education Interventions

4.2. Women’s Health and Techniques for Health Education and Promotion

4.3. Focus Group Discussions, Motivational Interviews, and Health Education Interventions

4.4. Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Health Education Interventions

4.5. Lack of Educational Interventions Linked to Noncommunicable Diseases

4.6. HIV and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections

4.7. Limitations

- The results of this narrative review should be interpreted with caution due to specific study limitations of the literature included, such as the small sample size of some of the quantitative studies (n < 100).

- We did not perform a quality assessment of the studies included (using checklists such as PRISMA, AMSTAR, or SANRA) as this study is a narrative review and was not intended to be a systematic review or meta-analysis.

- The limitation of the study language was a limitation in the present study.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parikh, N.S.; Parker, R.M.; Nurss, J.R.; Baker, D.W.; Williams, M.V. Shame and health literacy: The unspoken connection. Patient Educ. Couns. 1996, 27, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, M.S.; Williams, M.V.; Parker, R.M.; Parikh, N.S.; Nowlan, A.W.; Baker, D.W. Patients’ Shame and Attitudes Toward Discussing the Results of Literacy Screening. J. Health Commun. 2007, 12, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donelle, L.; Hall, J.; Benbow, S. A case study of the health literacy of a criminalized woman. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2015, 53, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, S.; Gover, A.R.; Koons-Witt, B.; Inabnit, B. The Successful Completion of Probation and Parole Among Female Offenders. Women Crim. Justice 2005, 17, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, C.; Kurtz-Rossi, S.; McKinney, J.; Pleasant, A.; Rootman, I.; Shohet, L. The Calgary Charter on Health Literacy: Rationale and Core Principles for the Development of Health Literacy Curricula; The Centre for Literacy: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Health Promotion Glossary; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Berk, J.; Ding, A.; Rich, J. Health Effects of Incarceration. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger, I.A.; Stern, M.F.; Deyo, R.A.; Heagerty, P.J.; Cheadle, A.; Elmore, J.G.; Koepsell, T.D. Release from Prison—A High Risk of Death for Former Inmates. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeever, A.; O’Donovan, D.; Kee, F. Factors influencing compliance with Hepatitis C treatment in patients transitioning from prison to community—A summary scoping review. J. Viral Hepat. 2023, 30, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mital, S.; Wolff, J.; Carroll, J.J. The relationship between incarceration history and overdose in North America: A scoping review of the evidence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020, 213, 108088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.W.; Sears, J.M.; Fulton-Kehoe, D. Overdose and substance-related mortality after release from prison in Washington State: 2014–2019. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022, 241, 109655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, D. Pesquisas em cadeia. Rev. Direito GV 2015, 11, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Scherer, Z.A.P. Mulheres Aprisionadas: Representações Sociais de Violência [Livre-Docência]; Escola de Enfermagem de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo: Ribeirão Preto, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marlow, E.; White, M.C.; Chesla, C.A. Barriers and Facilitators: Parolees’ Perceptions of Community Health Care. J. Correct. Health Care 2010, 16, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, K.; Boutwell, A.; Brockmann, B.W.; Rich, J.D. Integrating Correctional And Community Health Care For Formerly Incarcerated People Who Are Eligible For Medicaid. Health Aff. 2014, 33, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs, J. Reviewers’ Manual Edition 2014; The Joanna The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2014; ISBN 978-1-920684-11-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, J.D.; Lord, M.; Kapu, A.N.; Buckner, E. Promoting Adaptation in Female Inmates to Reduce Risk of Opioid Overdose Post-Release Through HOPE. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2022, 35, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brousseau, E.C.; Clarke, J.G.; Dumont, D.; Stein, L.A.R.; Roberts, M.; van den Berg, J. Computer-assisted motivational interviewing for contraceptive use in women leaving prison: A randomized controlled trial. Contraception 2020, 101, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsino, P.K.D.; do Nascimento, V.F.; Lucieto, G.C.; Hattori, T.Y.; da Graça, B.C.; Espinosa, M.M.; Terças-Trettel, A.C.P. Eficácia de Ação Educativa com Reeducandas de Cadeia Pública de Mato Grosso Sobre o Vírus HPV. Saúde Pesqui. 2018, 11, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, K.; Sedillo, M.L.; Kalishman, S.; Page, K.; Arora, S. The New Mexico Peer Education Project: Filling a Critical Gap in HCV Prison Education. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2018, 29, 1544–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, Y.V.; Moya, M.H.; Poulot, M.S. Formación de reclusos como promotores de salud para la prevención del contagio de sífilis en un centro penitenciario. MediSan 2016, 20, 795–802. [Google Scholar]

- Sifunda, S.; Reddy, P.S.; Braithwaite, R.; Stephens, T.; Bhengu, S.; Ruiter, R.A.; Van Den Borne, B. The Effectiveness of a Peer-Led HIV/AIDS and STI Health Education Intervention for Prison Inmates in South Africa. Health Educ. Behav. 2008, 35, 494–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle Yanes, I.; del Río Ysla, M.; Barreto Echemendía, E. Intervención educativa sobre VIH/SIDA en población penal de la provincia de Ciego de Ávila. Mediciego 2008, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Minc, A.; Butler, T.; Gahan, G. The Jailbreak Health Project—Incorporating a unique radio programme for prisoners. Int. J. Drug Policy 2007, 18, 444–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.C.; Duong, T.M.; Cruz, E.S.; Rodas, A.; McCall, C.; Menéndez, E.; Carmody, E.R.; Tulsky, J.P. Strategies for Effective Education in a Jail Setting: The Tuberculosis Prevention Project. Health Promot. Pract. 2003, 4, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinstead, O.; Zack, B.; Faigeles, B. Reducing Postrelease Risk Behavior among HIV Seropositive Prison Inmates: The Health Promotion Program. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2001, 13, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Bassel, N.; Ivanoff, A.; Schilling, R.F.; Borne, D.; Gilbert, L. Skills Building and Social Support Enhancement to Reduce HIV Risk among Women in Jail. Crim. Justice Behav. 1997, 24, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geana, M.V.; Anderson, S.; Lipnicky, A.; Wickliffe, J.L.; Ramaswamy, M. Managing Technology, Content, and User Experience: An mHealth Intervention to Improve Women’s Health Literacy after Incarceration. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2021, 32, 106–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.P.; Myles, R.L.; Sperling, C.C.; Carey, D. An Intervention for Reducing the Sexual Risk of Men Released From Jails. J. Correct. Health Care 2018, 24, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkelman, T.N.; Ford, B.R.; Dunsiger, S.; Chrastek, M.; Cameron, S.; Strother, E.; Bock, B.C.; Busch, A.M. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Smoking Cessation Program for Individuals Released From an Urban, Pretrial Jail. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2115687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banta-Green, C.J.; Williams, J.R.; Sears, J.M.; Floyd, A.S.; Tsui, J.I.; Hoeft, T.J. Impact of a jail-based treatment decision-making intervention on post-release initiation of medications for opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2020, 207, 107799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersema, J.J.; Santella, A.J.; Dansby, A.; Jordan, A.O. Adaptation of an Evidence-Based Intervention to Reduce HIV Risk in an Underserved Population: Young Minority Men in New York City Jails. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2019, 31, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staton, M.; Strickland, J.C.; Webster, J.M.; Leukefeld, C.; Oser, C.; Pike, E. HIV Prevention in Rural Appalachian Jails: Implications for Re-entry Risk Reduction Among Women Who Use Drugs. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 4009–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogel, C.I.; Crandell, J.L.; Neevel, A.M.; Parker, S.D.; Carry, M.; White, B.L.; Fasula, A.M.; Herbst, J.H.; Gelaude, D.J. Efficacy of an Adapted HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infection Prevention Intervention for Incarcerated Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crundall, I.; Deacon, K. A Prison-Based Alcohol Use Education Program: Evaluation of a Pilot Study. Subst. Use Misuse 1997, 32, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBel, T.P.; Maruna, S. Life on the Outside: Transitioning from Prison to the Community; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, D.; Wang, X. Does in-prison physical and mental health impact recidivism? SSM Popul. Health 2020, 11, 100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, S.; Smith-Rohrberg, D.; Hanck, S.; Altice, F.L. HIV testing in correctional institutions: Evaluating existing strategies, setting new standards. AIDS Public Policy J. 2005, 20, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Udo, T. Chronic medical conditions in U.S. adults with incarceration history. Health Psychol. 2019, 38, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donelle, L.; Hall, J. An Exploration of Women Offenders’ Health Literacy. Soc. Work. Public Health 2014, 29, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bergh, B.; Gatherer, A.; Fraser, A.; Moller, L. Imprisonment and women’s health: Concerns about gender sensitivity, human rights and public health. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011, 89, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, M.L.; Wickliffe, J.; Emerson, A.; Smith, S.; Ramaswamy, M. Justice-involved women’s preferences for an internet-based Sexual Health Empowerment curriculum. Int. J. Prison Health 2019, 16, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramagiri, R.; Kannuri, N.; Lewis, M.; Murthy, G.S.; Gilbert, C. Evaluation of whether health education using video technology increases the uptake of screening for diabetic retinopathy among individuals with diabetes in a slum population in Hyderabad. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 68, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change; Guillford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Weir, B.W.; O’Brien, K.; Bard, R.S.; Casciato, C.J.; Maher, J.E.; Dent, C.W.; Dougherty, J.A.; Stark, M.J. Reducing HIV and Partner Violence Risk Among Women with Criminal Justice System Involvement: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Two Motivational Interviewing-based Interventions. AIDS Behav. 2009, 13, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pederson, S.D.; Curley, E.J.; Collins, C.J. A Systematic Review of Motivational Interviewing to Address Substance Use with Justice-Involved Adults. Subst. Use Misuse 2021, 56, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.G.; Dongier, M.; Ouimet, M.C.; Tremblay, J.; Chanut, F.; Legault, L.; Ng Ying Kin, N.M.K. Brief Motivational Interviewing for DWI Recidivists Who Abuse Alcohol and Are Not Participating in DWI Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2010, 34, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaz, V.; Moreira, D.; Souza Cruz, O. Criminal reactions to drug-using offenders: A systematic review of the effect of treatment and/or punishment on reduction of drug use and/or criminal recidivism. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, J.; Gu, X. Utilization of addiction treatment among U.S. adults with history of incarceration and substance use disorders. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2019, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binswanger, I.A.; Krueger, P.M.; Steiner, J.F. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildeman, C.; Wang, E.A. Mass incarceration, public health, and widening inequality in the USA. Lancet 2017, 389, 1464–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.A.; Redmond, N.; Dennison Himmelfarb, C.R.; Pettit, B.; Stern, M.; Chen, J.; Shero, S.; Iturriaga, E.; Sorlie, P.; Diez Roux, A.V. Cardiovascular Disease in Incarcerated Populations. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 2967–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.; Lazaris, A.; O’Moore, É.; Plugge, E.; Stürup-Toft, S. Leaving no one behind in prison: Improving the health of people in prison as a key contributor to meeting the Sustainable Development Goals 2030. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e004252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocoros, N.; Nettle, E.; Church, D.; Bourassa, L.; Sherwin, V.; Cranston, K.; Carr, R.; Fukuda, H.D.; DeMaria, A., Jr. Screening for Hepatitis C as a Prevention Enhancement (SHAPE) for HIV: An Integration Pilot Initiative in a Massachusetts County Correctional Facility. Public Health Rep. 2014, 129, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.K.; Glover, D.A.; Wyatt, G.E.; Kisler, K.; Liu, H.; Zhang, M. A sexual risk and stress reduction intervention designed for HIV-positive bisexual African American men with childhood sexual abuse histories. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1476–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasula, A.M.; Fogel, C.I.; Gelaude, D.; Carry, M.; Gaiter, J.; Parker, S. Project Power: Adapting an Evidence-Based HIV/STI Prevention Intervention for Incarcerated Women. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2013, 25, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bonato, P.d.P.Q.; Ventura, C.A.A.; Maulide Cane, R.; Craveiro, I. Health Education Initiatives for People Who Have Experienced Prison: A Narrative Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020274

Bonato PdPQ, Ventura CAA, Maulide Cane R, Craveiro I. Health Education Initiatives for People Who Have Experienced Prison: A Narrative Review. Healthcare. 2024; 12(2):274. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020274

Chicago/Turabian StyleBonato, Patrícia de Paula Queiroz, Carla Aparecida Arena Ventura, Réka Maulide Cane, and Isabel Craveiro. 2024. "Health Education Initiatives for People Who Have Experienced Prison: A Narrative Review" Healthcare 12, no. 2: 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020274

APA StyleBonato, P. d. P. Q., Ventura, C. A. A., Maulide Cane, R., & Craveiro, I. (2024). Health Education Initiatives for People Who Have Experienced Prison: A Narrative Review. Healthcare, 12(2), 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020274