Identifying the Black Country’s Top Mental Health Research Priorities Using a Collaborative Workshop Approach: Community Connexions

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Aim

3. Objectives

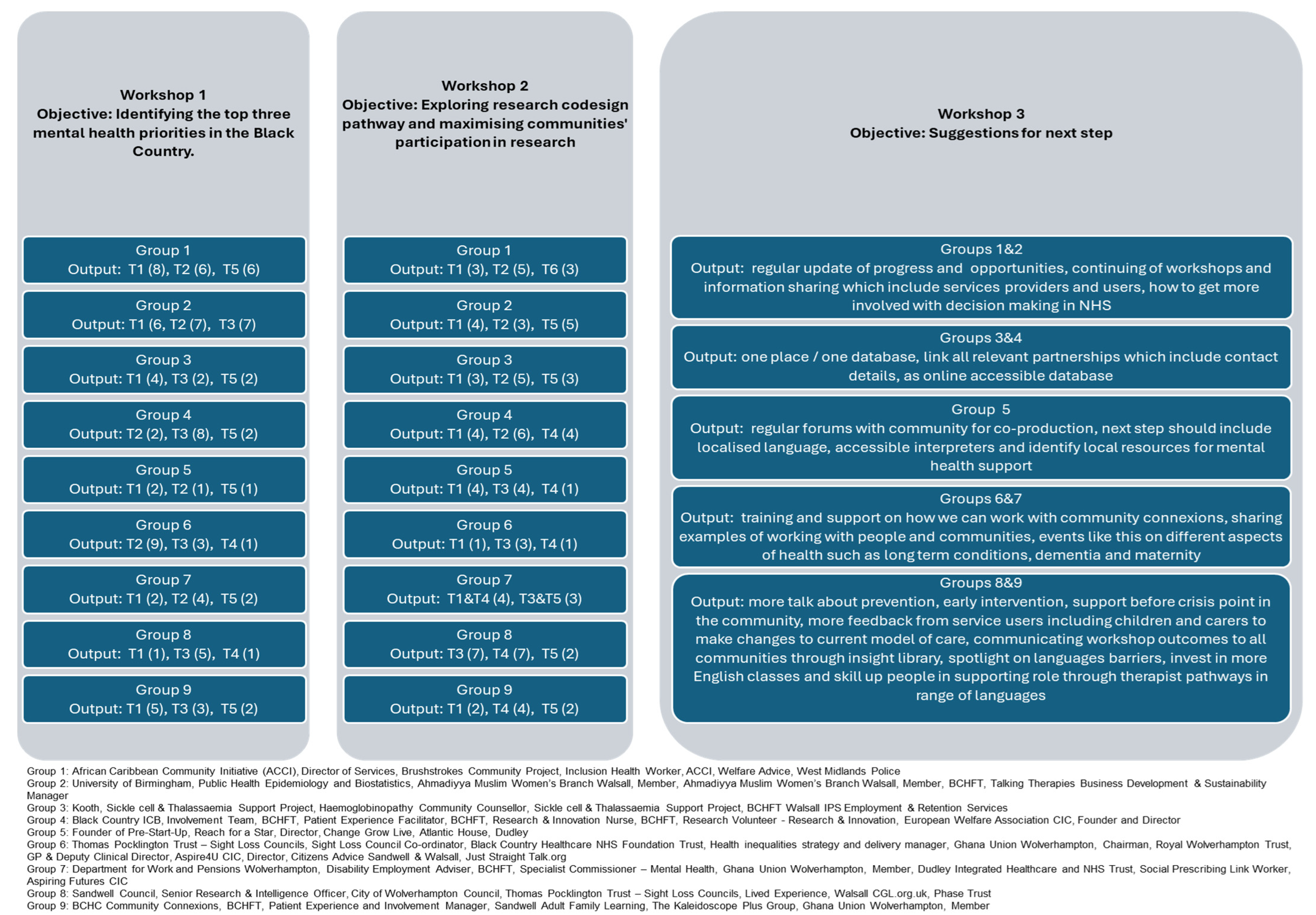

- Identifying the Black Country’s top 3 mental health priorities (WS-1);

- Utilising research to explore solutions for the identified issues (WS-2);

- Identifying the next step approach (WS-3).

4. Setting

5. Methods

6. Participants

7. Data Collection Tools, Instruments and Procedures

8. Workshops

| SQ1: What mental health challenges do you or people around you face on a regular basis? SQ2: In your opinion, what are the top 3 priorities for improving mental health support in our local communities? SQ3: What resources or support do you feel are lacking for addressing mental health needs? SQ4: How accessible are mental health services for individuals in underserved populations? Qualitative methods enabled the capturing of a wide range of experiences. |

| SQ1: What specific challenges do underserved populations face when they need to access mental health support? SQ2: What resources are currently available, and how can we make them more accessible and visible to those who need them most? SQ3: How can we collaborate with local organisations and community leaders to raise awareness and reduce stigma surrounding mental health? SQ4: What innovative approaches or strategies can we implement to ensure long-term sustainability and effectiveness in addressing these mental health priorities? |

9. Results

10. Discussion

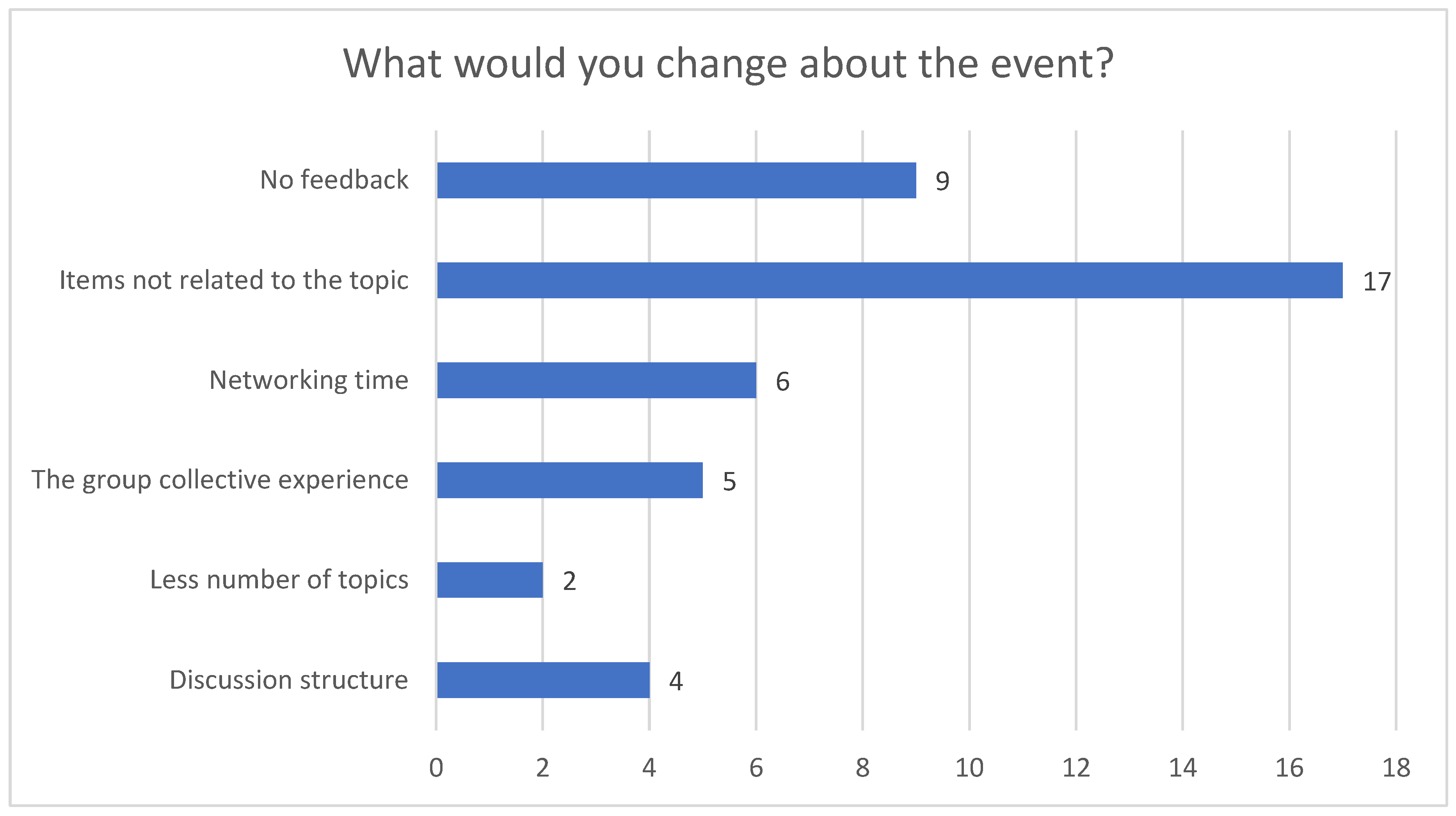

11. Limitations

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chitham, E. The Black Country; Amberley Publishing: Stroud, UK, 2009; p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.M. Industrial Enlightenment Science, Technology and Culture in BIRMINGHAM and the West Midlands 1760–1820, 1st ed.; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Anon. Homepage Black Country: Black Country Healthcare, NHS Foundation Trust. 2024. Available online: https://www.blackcountryhealthcare.nhs.uk/ (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Anon. NHS Black Country Joint Forward Plan 2023-2028 Updated April 2024 Black Country: Black Country Integrated Care Board. 2024. Available online: https://blackcountry.icb.nhs.uk/documents-resources/key-documents/navigate/17156/2859#ccm-block-document-library-17156 (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Blake, W.J.; Johnson, M.L.; Grant, J.E. Blake’s Poetry and Designs, Norton Critical Edition; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Economic Intelligence Unit. Black Country & West Birmingham Socio-Economic Profile July 2020 Black Country: Black Country Consortium, Economic Intelligence Unit. Available online: https://www.strategyunitwm.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/2020-10/BCWB%20Socioeconomic%20Profile%20July%202020%20-%20Final.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Vertovec, S. Talking around super-diversity. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2019, 42, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhugra, D.; Wijesuriya, R.; Gnanapragasam, S.; Persaud, A. Black and minority mental health in the UK: Challenges and solutions. Forensic Sci. Int. Mind Law 2020, 1, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memon, A.; Taylor, K.; Mohebati, L.M.; Sundin, J.; Cooper, M.; Scanlon, T.; de Visser, R. Perceived barriers to accessing mental health services among black and minority ethnic (BME) communities: A qualitative study in Southeast England. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahad, A.A.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, M.; Junquera, P. Understanding and Addressing Mental Health Stigma Across Cultures for Improving Psychiatric Care: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e39549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomeer, M.B.; Moody, M.D.; Yahirun, J. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Mental Health and Mental Health Care During The COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2023, 10, 961–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrissey, H.; Benoit, C.; Ball, P.A.; Galbraith, N.; Lim, J.; Burt, C.; Wandroo, F. Exploring The Attitude Of The UK Diverse Ethnic Communities Towards COVID-19 Public Health Announcements. Eur. J. Biomed. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 13, 303–324. [Google Scholar]

- Koodun, S.; Dudhia, R.; Abifarin, B.; Greenhalgh, N. Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health care. Pharm. J. 2021, 307, 810–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anon. Community Connexions Birmingham: Birmingham Community Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust. 2024. Available online: https://www.bhamcommunity.nhs.uk/community-connexions/ (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Anon. Best Care: Healthy Communities, We are Birmingham Community Healthcare Birmingham: Birmingham Community Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust. 2024. Available online: https://www.bhamcommunity.nhs.uk/ (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Anon. Community Mental Health Transformation Black Country: Black Country Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust. 2024. Available online: https://www.blackcountryhealthcare.nhs.uk/about-us/community-mental-health-transformation (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Santana de Lima, E.; Preece, C.; Potter, K.; Goddard, E.; Edbrooke-Childs, J.; Hobbs, T.; Fonagy, P. A community-based approach to identifying and prioritising young people’s mental health needs in their local communities. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2023, 9, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, P.F.C.; Williamson, S.; Alderwick, H. Integrated Care Systems: What do They Look Like? The Health Foundation: London, UK, 2022; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Anon. Mental Health, Learning Disabilities and Autism Black Country: NHS Black Country Integrated Care Board. 2022. Available online: https://blackcountry.icb.nhs.uk/about-us/our-priorities/our-5-year-joint-forward-plan/mental-health-learning-disabilities-and-autism (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Vygotsky, L. Interaction between Learning and Development. Read. Dev. Child. 1978, 23, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.S.; Vella, S.; Challies, E.; de Vente, J.; Frewer, L.; Hohenwallner-Ries, D.; Huber, T.; Neumann, R.K.; Oughton, E.A.; Sidoli del Ceno, J.; et al. A theory of participation: What makes stakeholder and public engagement in environmental management work? Restor. Ecol. 2018, 26 (Suppl. S1), S7–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Gould, R.K.; Wojcik, D.; Wyman Roth, N.; Biggar, M. Community listening sessions: An approach for facilitating collective reflection on environmental learning and behavior in everyday life. Ecosyst. People 2022, 18, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniot, C.; Ackom-Mensah, H.; Burt, C.; Zakia, F.; Siddiqi, U. Community Connexions Engagement Handbook. Engaging with Underserved Communities Birmingham: Birmingham Community Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust. 2023. Available online: https://www.aston.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2024-01/community-connexions-engagement-handbook.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Formby, E. Why You Should Think Twice Before You Talk about ‘the LGBT Community’ Melbourne Australia: The Conversation. 2017. Available online: https://theconversation.com/why-you-should-think-twice-before-you-talk-about-the-lgbt-community-81711 (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- NHS Enlgand. Allocations: NHS England. 2023. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/allocations/ (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Rocks, S.F.; Kissa, Z.; Boccarini, G. Health Care Funding: The Health Foundation. Available online: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/health-care-funding (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Ahmed, M.; Morrissey, H.; Ball, P.A. A Critical Review and Local Audit of the Prevalence of Mental Ill-Health in Heart Failure Patients. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 12, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, N.; Wara, B.; Morrissey, H.; Ball, P. Impact of Mental Ill Health on Medication Adherence Behaviour in Patients Diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes. Arch. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 12, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.; Chelminski, I.; Young, D.; Dalrymple, K. A clinically useful anxiety outcome scale. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 71, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, M.; Chelminski, I.; McGlinchey, J.B.; Posternak, M.A. A clinically useful depression outcome scale. Compr. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langley, C.A.; Bush, J. The Aston Medication Adherence Study: Mapping the adherence patterns of an inner-city population. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2014, 36, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, N.; Karlsen, S.; Sashidharan, S.P.; Cohen, R.; Chew-Graham, C.A.; Malpass, A. Understanding ethnic inequalities in mental healthcare in the UK: A meta-ethnography. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1004139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winsper, C.; Bhattacharya, R.; Bhui, K.; Currie, G.; Edge, D.; Ellard, D.R.; Franklin, D.; Gill, P.S.; Gilbert, S.; Miller, R.; et al. Improving mental healthcare access and experience for people from minority ethnic groups: An England-wide multisite experience-based codesign (EBCD) study. BMJ Ment. Health 2023, 26, e300709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, S. London: The King’s Fund. 2019. Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/blogs/race-inequalities-nhs-workforce (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Neville, S.; Wrapson, W.; Savila, F.; Napier, S.; Paterson, J.; Dewes, O.; Soon, H.N.W.; Tautolo, E.-S. Barriers to older Pacific peoples’ participation in the health-care system in Aotearoa New Zealand. J. Prim. Health Care 2022, 14, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Codes Number | Codes Name | Frequencies | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Code 12 | Ineligibility to access healthcare | 17 | 1.98 |

| Code 4 | Few face-to-face appointments | 22 | 2.56 |

| Code 1 | Few practices | 34 | 3.96 |

| Code 3 | Large number of patients | 37 | 4.31 |

| Code 11 | Poor self-care, self-worth or self-care capacity | 44 | 5.12 |

| Code 7 | Poor patient experience | 48 | 5.59 |

| Code 5 | Shift from on-site family GP-led care to generic GP care, generic allied health care, online appointments or self-care | 66 | 7.68 |

| Code 2 | Limited appropriately trained workforce | 82 | 9.55 |

| Code 6 | Change in patient expectations | 109 | 12.69 |

| Code 10 | Poor communication between patients and healthcare professionals | 116 | 13.50 |

| Code 8 | Complex healthcare needs | 134 | 15.60 |

| Code 9 | Disparity due to language, culture, beliefs, age, gender and socioeconomic status | 150 | 17.46 |

| Themes | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workshop 1 | n = 116 | ||

| 1 | Barriers to appropriate healthcare | 29 | 25% |

| 2 | Inappropriate prioritisation of accessible funded healthcare needs | 25 | 22% |

| 3 | Limited resources for training, health promotion, preventative care and support networks | 36 | 31% |

| 4 | New health services model | 7 | 6% |

| 5 | Poor access to needed care | 19 | 16% |

| Workshop 2 | n = 117 | ||

| 1 | Research on barriers and enablers to access the needed care | 24 | 20.5% |

| 2 | Research on the appropriate prioritisation of accessible funded healthcare need | 17 | 14.5% |

| 3 | Research on the needed resources for training, health promotion, preventative care and support networks | 26 | 22% |

| 4 | Research on a new health services model | 28 | 24% |

| 5 | Research for patient benefit, not researchers, healthcare professionals or government | 22 | 19% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morrissey, H.; Benoit, C.; Ball, P.A.; Ackom-Mensah, H. Identifying the Black Country’s Top Mental Health Research Priorities Using a Collaborative Workshop Approach: Community Connexions. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2506. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242506

Morrissey H, Benoit C, Ball PA, Ackom-Mensah H. Identifying the Black Country’s Top Mental Health Research Priorities Using a Collaborative Workshop Approach: Community Connexions. Healthcare. 2024; 12(24):2506. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242506

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorrissey, Hana, Celine Benoit, Patrick Anthony Ball, and Hannah Ackom-Mensah. 2024. "Identifying the Black Country’s Top Mental Health Research Priorities Using a Collaborative Workshop Approach: Community Connexions" Healthcare 12, no. 24: 2506. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242506

APA StyleMorrissey, H., Benoit, C., Ball, P. A., & Ackom-Mensah, H. (2024). Identifying the Black Country’s Top Mental Health Research Priorities Using a Collaborative Workshop Approach: Community Connexions. Healthcare, 12(24), 2506. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242506