Impact of Workplace Bullying on Quiet Quitting in Nurses: The Mediating Effect of Coping Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Measures

2.3. Ethical Issues

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Job Characteristics

3.2. Study Scales

3.3. Correlation Analysis

3.4. Regression Analysis

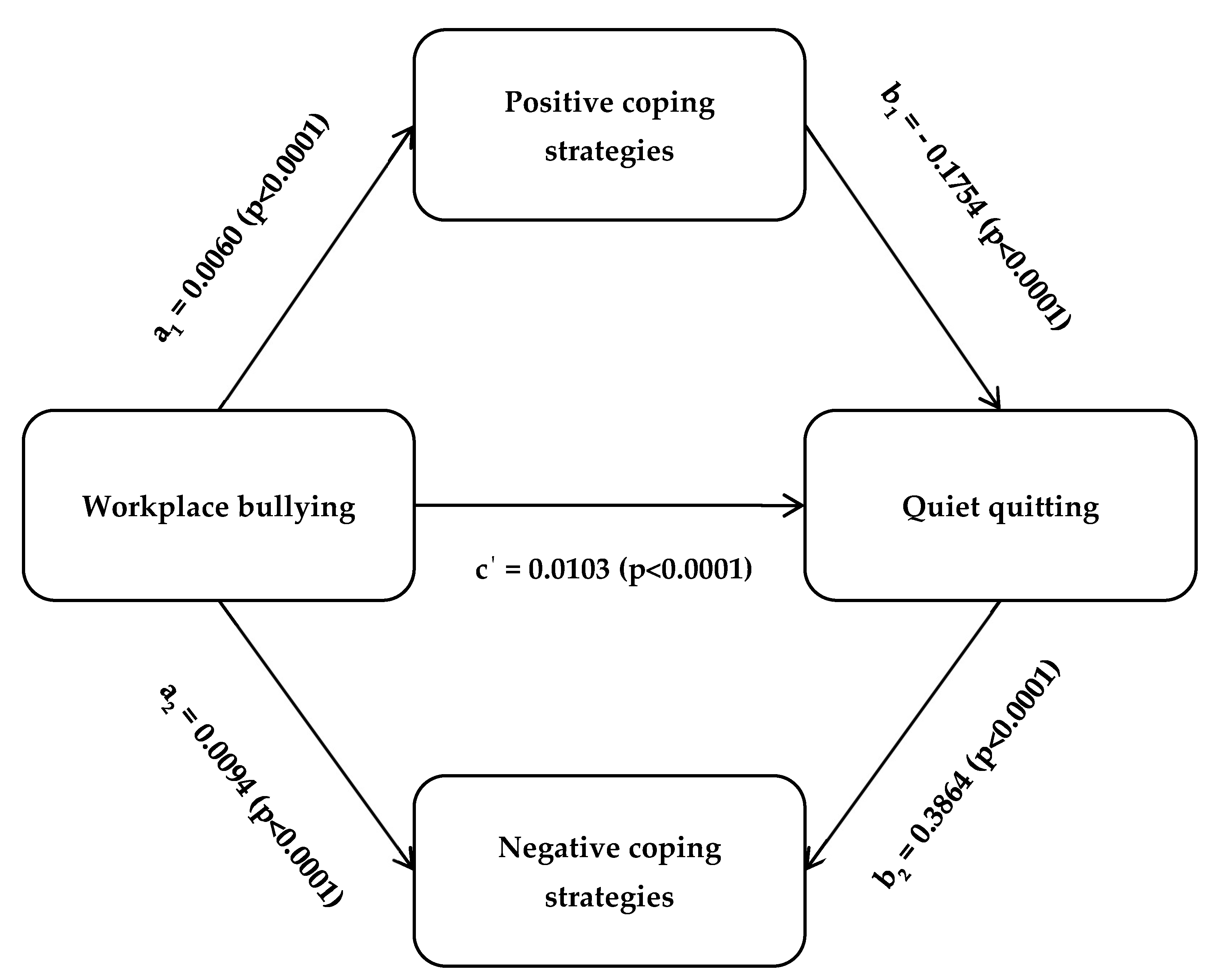

3.5. Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Einarsen, S. Harassment and Bullying at Work: A Review of the Scandinavian Approach. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2000, 5, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purpora, C.; Cooper, A.; Sharifi, C.; Lieggi, M. Workplace Bullying and Risk of Burnout in Nurses: A Systematic Review Protocol. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2019, 17, 2532–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Einarsen, S.V. What We Know, What We Do Not Know, and What We Should and Could Have Known about Workplace Bullying: An Overview of the Literature and Agenda for Future Research. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018, 42, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahm, G.B.; Rystedt, I.; Wilde-Larsson, B.; Nordström, G.; Strandmark, K.M. Workplace Bullying among Healthcare Professionals in Sweden: A Descriptive Study. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2019, 33, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awai, N.S.; Ganasegeran, K.; Manaf, M.R.A. Prevalence of Workplace Bullying and Its Associated Factors among Workers in a Malaysian Public University Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Study. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bambi, S.; Foà, C.; De Felippis, C.; Lucchini, A.; Guazzini, A.; Rasero, L. Workplace Incivility, Lateral Violence and Bullying among Nurses. A Review about Their Prevalence and Related Factors. Acta Bio Med. Atenei Parm. 2018, 89, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin, L.; Sak-Dankosky, N.; Czarkowska-Pączek, B. Bullying in Nursing Evaluated by the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 1320–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorey, S.; Wong, P.Z.E. A Qualitative Systematic Review on Nurses’ Experiences of Workplace Bullying and Implications for Nursing Practice. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 4306–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatuna, I.; Jönsson, S.; Muhonen, T. Workplace Bullying in the Nursing Profession: A Cross-Cultural Scoping Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 111, 103628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, H.S.; Hosier, S.; Zhang, H. Prevalence, Antecedents, and Consequences of Workplace Bullying among Nurses—A Summary of Reviews. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusiewicz, C.V.; Shirey, M.R.; Patrician, P.A. Workplace Bullying and Newly Licensed Registered Nurses: An Evolutionary Concept Analysis. Workplace Health Saf. 2019, 67, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanis, P.; Moisoglou, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Mastrogianni, M. Association between Workplace Bullying, Job Stress, and Professional Quality of Life in Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.H.; Benham-Hutchins, M. The Influence of Bullying on Nursing Practice Errors: A Systematic Review. AORN J. 2020, 111, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnetz, J.E.; Neufcourt, L.; Sudan, S.; Arnetz, B.B.; Maiti, T.; Viens, F. Nurse-Reported Bullying and Documented Adverse Patient Events: An Exploratory Study in a US Hospital. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2020, 35, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogh, A.; Baernholdt, M.; Clausen, T. Impact of Workplace Bullying on Missed Nursing Care and Quality of Care in the Eldercare Sector. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2018, 91, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Muharraq, E.H.; Baker, O.G.; Alallah, S.M. The Prevalence and The Relationship of Workplace Bullying and Nurses Turnover Intentions: A Cross Sectional Study. SAGE Open Nurs. 2022, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnetz, J.E.; Sudan, S.; Fitzpatrick, L.; Cotten, S.R.; Jodoin, C.; Chang, C.H.; Arnetz, B.B. Organizational Determinants of Bullying and Work Disengagement among Hospital Nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 1229–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, D.; Tharp-Barrie, K.; Kay Rayens, M. Experience of Nursing Leaders with Workplace Bullying and How to Best Cope. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.Y.; Ahn, H.Y. Nurses’ Workplace Bullying Experiences, Responses, and Ways of Coping. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- João, A.L.; Portelada, A. Coping with Workplace Bullying: Strategies Employed by Nurses in the Healthcare Setting. Nurs. Forum 2023, 2023, 8447804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyett, A. Quiet Quitting. Soc. Work. 2022, 68, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuzelo, P.R. Discouraging Quiet Quitting: Potential Strategies for Nurses. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2023, 37, 174–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, J. Quiet Quitting Is a New Name for an Old Method of Industrial Action. Conversat. 2022. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363415148_Quiet_quitting_is_a_new_name_for_an_old_method_of_industrial_action (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Harter, J. Is Quiet Quitting Real? Available online: https://www.gallup.com/workplace/398306/quiet-quitting-real.aspx (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Galanis, P.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Moisoglou, I.; Gallos, P.; Kaitelidou, D. The Quiet Quitting Scale: Development and Initial Validation. AIMS Public Health 2023, 10, 828–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanis, P.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Katsoulas, T.; Moisoglou, I.; Gallos, P.; Kaitelidou, D. Nurses Quietly Quit Their Job More Often than Other Healthcare Workers: An Alarming Issue for Healthcare Services. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38193567/ (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Galanis, P.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Katsoulas, T.; Moisoglou, I.; Gallos, P.; Kaitelidou, D. The Influence of Job Burnout on Quiet Quitting among Nurses: The Mediating Effect of Job Satisfaction. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372094983_The_influence_of_job_burnout_on_quiet_quitting_among_nurses_the_mediating_effect_of_job_satisfaction (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Galanis, P.; Moisoglou, I.; Malliarou, M.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Kaitelidou, D. Quiet Quitting among Nurses Increases Their Turnover Intention: Evidence from Greece in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Healthcare 2024, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanis, P.; Moisoglou, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Kaitelidou, D. Moral Resilience Reduces Levels of Quiet Quitting, Job Burnout, and Turnover Intention among Nurses: Evidence in the Post COVID-19 Era. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, K.J. Assessing Coping Strategies: A Theoretically Based Approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.F.; Kuo, C.C.; Chien, T.W.; Wang, Y.R. A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Coping Strategies on Reducing Nurse Burnout. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2016, 31, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Barmawi, M.A.; Subih, M.; Salameh, O.; Sayyah Yousef Sayyah, N.; Shoqirat, N.; Abdel-Azeez Eid Abu Jebbeh, R. Coping Strategies as Moderating Factors to Compassion Fatigue among Critical Care Nurses. Brain Behav. 2019, 9, e01264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.S.H.; Tzeng, W.C.; Chiang, H.H. Impact of Coping Strategies on Nurses’ Well-Being and Practice. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2019, 51, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, K.Q.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Abdul-Manan, H.H.; Mohd-Salleh, Z.A.H.; Abdul-Mumin, K.H.; Rahman, H.A. Strategies Used to Cope with Stress by Emergency and Critical Care Nurses. Br. J. Nurs. 2019, 28, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Notelaers, G. Measuring Exposure to Bullying and Harassment at Work: Validity, Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised. Work Stress 2009, 23, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoulakis, C.; Galanakis, M.; Bakoula-Tzoumaka, C.; Darvyri, P.; Chroussos, G.; Darvyri, C. Validation of the Negative Acts Questionnaire (NAQ) in a Sample of Greek Teachers. Psychology 2015, 6, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Galanis, P.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Moisoglou, I.; Gallos, P.; Kaitelidou, D. Quiet Quitting among Employees: A Proposed Cut-off Score for the “Quiet Quitting” Scale. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/371843640_Quiet_quitting_among_employees_a_proposed_cut-off_score_for_the_Quiet_Quitting_Scale (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Carver, C.S. You Want to Measure Coping but Your Protocol’s Too Long: Consider the Brief COPE. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapsou, M.; Panayiotou, G.; Kokkinos, C.M.; Demetriou, A.G. Dimensionality of Coping: An Empirical Contribution to the Construct Validation of the Brief-COPE with a Greek-Speaking Sample. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solberg, M.A.; Gridley, M.K.; Peters, R.M. The Factor Structure of the Brief Cope: A Systematic Review. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 44, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hult, T.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 9781462534661. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen Hsiao, S.T.; Ma, S.C.; Guo, S.L.; Kao, C.C.; Tsai, J.C.; Chung, M.H.; Huang, H.C. The Role of Workplace Bullying in the Relationship between Occupational Burnout and Turnover Intentions of Clinical Nurses. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2022, 68, 151483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bambi, S.; Guazzini, A.; Piredda, M.; Lucchini, A.; De Marinis, M.G.; Rasero, L. Negative Interactions among Nurses: An Explorative Study on Lateral Violence and Bullying in Nursing Work Settings. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, S.R.; Kabir, H.; Mazumder, S.; Akter, N.; Chowdhury, M.R.; Hossain, A. Workplace Violence, Bullying, Burnout, Job Satisfaction and Their Correlation with Depression among Bangladeshi Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Survey during the COVID-19 Pandemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenger, J.; Folkman, J. Quiet Quitting Is about Bad Bosses, Not Bad Employees. Available online: https://hbr.org/2022/08/quiet-quitting-is-about-bad-bosses-not-bad-employees (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Fontes, K.B.; Alarcão, A.C.J.; Santana, R.G.; Pelloso, S.M.; de Barros Carvalho, M.D. Relationship between Leadership, Bullying in the Workplace and Turnover Intention among Nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olender, L. The Relationship between and Factors Influencing Staff Nurses’ Perceptions of Nurse Manager Caring and Exposure to Workplace Bullying in Multiple Healthcare Settings. J. Nurs. Adm. 2017, 47, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, K.C.; Oh, K.M.; Kitsantas, P.; Zhao, X. Workplace Bullying among Nurses and Organizational Response: An Online Cross-Sectional Study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, N.; Jeong, S.; Smith, T. Negative Workplace Behavior and Coping Strategies among Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2021, 23, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acquadro Maran, D.; Giacomini, G.; Scacchi, A.; Bigarella, R.; Magnavita, N.; Gianino, M.M. Consequences and Coping Strategies of Nurses and Registered Nurses Perceiving to Work in an Environment Characterized by Workplace Bullying. Dialogues Health 2024, 4, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castronovo, M.A.; Pullizzi, A.; Evans, S.K. Nurse Bullying: A Review And A Proposed Solution. Nurs. Outlook 2016, 64, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.P.; Westbrook, R.A.; Challagalla, G. Good Cope, Bad Cope: Adaptive and Maladaptive Coping Strategies Following a Critical Negative Work Event. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healy, C.M.; McKay, M.F. Nursing Stress: The Effects of Coping Strategies and Job Satisfaction in a Sample of Australian Nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 31, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, R.; Li, J.; Cheng, N.; Liu, X.; Tan, Y. The Mediating Role of Coping Styles between Nurses’ Workplace Bullying and Professional Quality of Life. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisoglou, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Malliarou, M.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Gallos, P.; Galanis, P. Social Support and Resilience Are Protective Factors against COVID-19 Pandemic Burnout and Job Burnout among Nurses in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Healthcare 2024, 12, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Luo, H.; Ma, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, X.; Huang, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; He, J.; Song, Y. Association between Workplace Bullying and Nurses’ Professional Quality of Life: The Mediating Role of Resilience. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 1549–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.H.; Wang, H.H.; Ma, S.C. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy in the Relationship between Workplace Bullying, Mental Health and an Intention to Leave among Nurses in Taiwan. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2019, 32, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Males | 82 | 12.3 |

| Females | 583 | 87.7 |

| Age (years) a | 38.9 | 10.1 |

| Understaffed department | ||

| No | 132 | 19.8 |

| Yes | 533 | 80.2 |

| Clinical experience (years) a | 14.1 | 10.2 |

| Shift work | ||

| No | 170 | 25.6 |

| Yes | 495 | 74.4 |

| Scale | Mean | Standard Deviation | Median | Minimum Value | Maximum Value | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Acts Questionnaire—Revised | 51.3 | 20.6 | 46.0 | 22 | 108 | 86 |

| Quiet Quitting Scale | 2.5 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Brief COPE | ||||||

| Positive coping strategies | 2.6 | 0.5 | 2.6 | 1 | 4 | 3 |

| Negative coping strategies | 2.0 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 1 | 4 | 3 |

| Variables | Quiet Quitting | Positive Coping Strategies | Negative Coping Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace bullying | 0.453 *** | 0.244 *** | 0.423 *** |

| Quiet quitting | 0.060 | 0.395 *** |

| Independent Variables | Coefficient Beta | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males vs. females | 0.156 | 0.041 to 0.271 | 0.008 |

| Age | −0.001 | −0.005 to 0.003 | 0.511 |

| Understaffed department (yes vs. no) | 0.033 | −0.064 to 0.130 | 0.508 |

| Shift work (yes vs. no) | 0.076 | −0.014 to 0.165 | 0.096 |

| Workplace bullying | 0.010 | 0.008 to 0.012 | <0.001 |

| Positive coping strategies | −0.169 | −0.251 to −0.087 | <0.001 |

| Negative coping strategies | 0.382 | 0.285 to 0.479 | <0.001 |

| Outcome | Mediation Analysis Paths | Regression Coefficient | SE | 95% Bias-Corrected CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | |||||

| Quiet quitting | Total effect | 0.0128 | 0.0010 | 0.0109 | 0.0147 | <0.0001 |

| Direct effect | 0.0103 | 0.0010 | 0.0082 | 0.0122 | <0.0001 | |

| Indirect effect of positive coping strategies | −0.0011 | 0.0003 | −0.0017 | −0.0005 | <0.0001 | |

| Indirect effect of negative coping strategies | 0.0036 | 0.0006 | 0.0084 | 0.0049 | <0.0001 | |

| Workplace bullying → Positive coping strategies | 0.0060 | 0.0090 | 0.0042 | 0.0078 | <0.0001 | |

| Positive coping strategies → Quiet quitting | −0.1754 | 0.0418 | −0.2574 | −0.0933 | <0.0001 | |

| Workplace bullying → Negative coping strategies | 0.0094 | 0.0008 | 0.0079 | 0.0110 | <0.0001 | |

| Negative coping strategies → Quiet quitting | 0.3864 | 0.0496 | 0.2891 | 0.4837 | <0.0001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galanis, P.; Moisoglou, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Malliarou, M.; Vraka, I.; Gallos, P.; Kalogeropoulou, M.; Papathanasiou, I.V. Impact of Workplace Bullying on Quiet Quitting in Nurses: The Mediating Effect of Coping Strategies. Healthcare 2024, 12, 797. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12070797

Galanis P, Moisoglou I, Katsiroumpa A, Malliarou M, Vraka I, Gallos P, Kalogeropoulou M, Papathanasiou IV. Impact of Workplace Bullying on Quiet Quitting in Nurses: The Mediating Effect of Coping Strategies. Healthcare. 2024; 12(7):797. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12070797

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalanis, Petros, Ioannis Moisoglou, Aglaia Katsiroumpa, Maria Malliarou, Irene Vraka, Parisis Gallos, Maria Kalogeropoulou, and Ioanna V. Papathanasiou. 2024. "Impact of Workplace Bullying on Quiet Quitting in Nurses: The Mediating Effect of Coping Strategies" Healthcare 12, no. 7: 797. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12070797

APA StyleGalanis, P., Moisoglou, I., Katsiroumpa, A., Malliarou, M., Vraka, I., Gallos, P., Kalogeropoulou, M., & Papathanasiou, I. V. (2024). Impact of Workplace Bullying on Quiet Quitting in Nurses: The Mediating Effect of Coping Strategies. Healthcare, 12(7), 797. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12070797