Line Immunoblot Assay for Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever and Findings in Patient Sera from Australia, Ukraine and the USA

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human Sera for Assessing Clinical Specificity of TBRF Immunoblots

2.2. Rabbit Antisera for Testing Antigenic Cross-Reactivity between RFB and LDB Proteins

2.3. Human Sera for Assessing Clinical Sensitivity of TBRF Immunoblots

2.4. Sera from Patients with LD-Like Symptoms

2.4.1. Australia

2.4.2. Ukraine

2.4.3. USA

2.5. Storage, Testing Approach, and Ethical Considerations with Human Sera

2.6. PCR Detection of RFB in Blood

2.7. Preparation of Antigen Strips for IBs

2.7.1. Antigens for LD Immunoblots

2.7.2. Antigens in TBRF Immunoblots

2.8. Detection of Antibodies in Patient Sera with TBRF and LD Immunoblots

2.8.1. Controls for Immunoblots

2.8.2. Scoring of Reactivity of Patient Sera in LD and TBRF Immunoblots

2.9. TBRF Immunoblots with Rabbit Antisera for Investigating Antigenic Cross-Reactivity between LDB and RFB Proteins

2.10. Statistical Analysis

2.11. Protein Sequence Homology Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Antigenic Cross-Reactivity between the LDB and RFB proteins

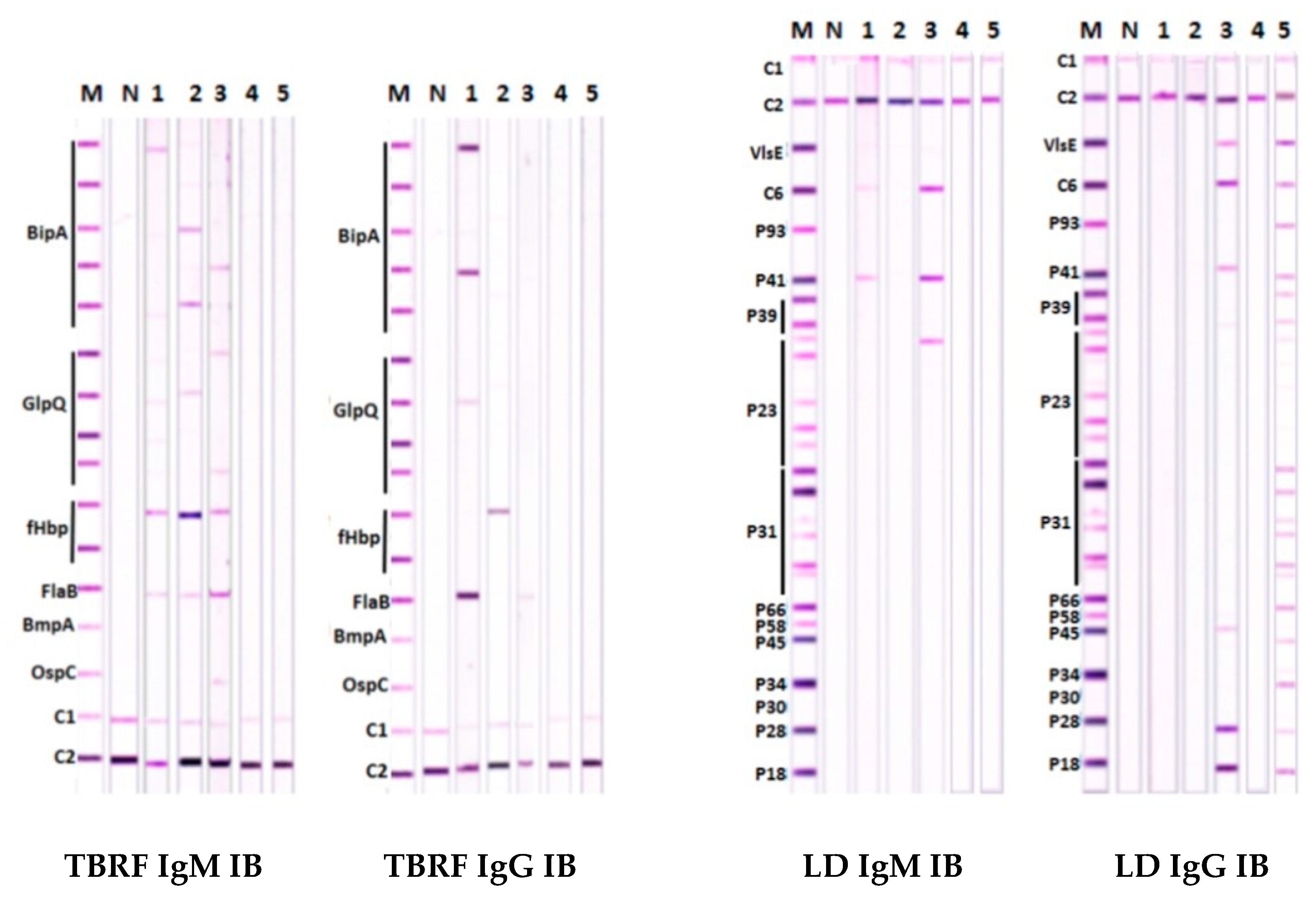

3.2. Scoring Algorithm to Optimize Specificity and Sensitivity of the TBRF IB Assay

3.2.1. Specificity of Detecting Antibodies in TBRF IBs

3.2.2. Sensitivity of Detecting Antibodies in TBRF IBs

3.2.3. Clinical Parameters of Antibody Detection in TBRF Immunoblots

3.3. Findings with TBRF and LD IB Assays in Patients with LD-Like Symptoms

4. Discussion

4.1. Specificity of TBRF IBs

4.2. Sensitivity of TBRF IBs

4.3. Identifying Infecting RFB Species from TBRF IB Findings

4.4. Implications of the Findings for the Epidemiology of TBRF and LD

4.5. TBRF and Malaria in Africa

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations

References

- Cutler, S.J.; Ruzic-Sabljic, E.; Potkonjak, A. Emerging borreliae—expanding beyond Lyme borreliosis. Mol. Cell. Probes 2017, 31, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margos, G.; Gofton, A.; Wibberg, D.; Dangel, A.; Marosevic, D.; Loh, S.-M.; Oskam, C.; Fingerle, V. The genus Borrelia reloaded. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme Disease. 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/index.html (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Stanek, G.; Wormser, G.P.; Gray, J.; Strle, F. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet 2012, 379, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotthoefer, A.M.; Frost, H.M. Ecology and epidemiology of Lyme borreliosis. Clin. Lab. Med. 2015, 35, 723–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovchenko, M.; Vancová, M.; Clark, K.; Oliver, J.H., Jr.; Grubhoffer, L.; Rudenko, N. A Divergent spirochete strain isolated from a resident of the southeastern United States was identified by multilocus sequence typing as Borrelia bissettii. Parasit Vectors. 2016, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritt, B.S.; Mead, P.S.; Johnson, D.K.H.; Neitzel, D.F.; Respicio-Kingry, L.B.; Davis, J.P.; Schiffman, E.; Sloan, L.M.; Schriefer, M.E.; Replogle, A.J.; et al. Identification of a novel pathogenic Borrelia species causing Lyme borreliosis with unusually high spirochaetaemia: A descriptive study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilske, B. Diagnosis of Lyme Borreliosis in Europe. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2003, 3, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Health. Position Statement: Lyme Disease in Australia. 2018. Available online: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/ohp-lyme-disease.htm/$File/Posit-State-Lyme-June18.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Chalada, M.J.; Stenos, J.; Bradbury, S. Is there a Lyme-like disease in Australia? Summary of the findings to date. One Health 2016, 2, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mayne, P.; Song, S.; Shao, R.; Burke, J.; Wang, Y.; Roberts, T. Evidence for Ixodes holocyclus (Acarina: Ixodidae) as a vector for human lyme Borreliosis infection in Australia. J. Insect Sci. 2014, 14, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, S. Relapsing fever—a forgotten disease revealed. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 108, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever (TBRF). 2015. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/relapsing-fever/index.html (accessed on 23 August 2018).

- Cutler, S.J. Relapsing fever Borreliae: A global review. Clin. Lab. Med. 2015, 5, 847–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Louse-Borne Relapsing Fever (LBRF). 2015. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/relapsing-fever/resources/louse.html (accessed on 23 August 2018).

- Talagrand-Reboul, E.; Boyer, P.H.; Bergström, S.; Vial, L.; Boulanger, N. Relapsing fevers: Neglected tick-borne diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingry, L.C.; Anacker, M.; Pritt, B.; Bjork, J.; Respicio-Kingry, L.; Liu, G.; Sheldon, S.; Boxrud, D.; Strain, A.; Oatman, S.; et al. Surveillance for and discovery of Borrelia species in US patients suspected of tick borne illness. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, 1864–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, J.E.; Krishnavahjala, A.; Garcia, M.N.; Bermudez, S. Tick-borne relapsing fever spirochetes in the Americas. Vet. Sci. 2016, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, M.; Lopes de Carvalho, I.; Figueiredo, M.; Amaro, F.; Boinas, F.; Cutler, S.J.; Núncio, M.S. Borrelia hispanica in Ornithodoros erraticus, Portugal. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elbir, H.; Larsson, P.; Normark, J.; Upreti, M.; Korenberg, E.; Larsson, C.; Bergström, S. Genome sequence of the Asiatic species Borrelia persica. Genome Announc. 2014, 2, e01127-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, P.J.; Fish, D.; Narasimhan, S.; Barbour, A.G. Borrelia miyamotoi infection in nature and in humans. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elbir, H.; Raoult, D.; Drancourt, M. Relapsing fever Borreliae in Africa. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013, 89, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Borrelia Miyamotoi. 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/miyamotoi.html. (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Burkot, T.R.; Mullen, G.R.; Anderson, R.; Schneider, B.S.; Happ, C.M.; Zeidner, N.S. Borrelia lonestari DNA in adult Amblyomma americanum ticks, Alabama. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2001, 7, 471–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middelveen, M.J.; Shah, J.S.; Fesler, M.C.; Stricker, R.B. Relapsing fever Borrelia in California: A pilot serological study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2018, 11, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, S. Refugee crisis and re-emergence of forgotten infections in Europe. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cameron, D.J.; Johnson, L.B.; Maloney, E.L. Evidence assessments and guideline recommendations in Lyme disease: The clinical management of known tick bites, erythema migrans rashes and persistent disease. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2014, 12, 1103–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, M.S.; Anderson, D.E., Jr.; Schwan, T.G.; Shoemaker, P.C.; Banerjee, S.N.; Kassen, B.O.; Burgdorfer, W. Tick-borne relapsing fever in the northwestern United States and southwestern Canada. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998, 26, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme Disease (Borrelia Burgdorferi) Case Definition. 2017. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/lyme-disease/case-definition/2017/ (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Stoenner, H.G. Antigenic variation of Borrelia hermsii. J. Exp. Med. 1982, 156, 1297–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbour, A.G.; Dai, Q.; Restrepo, B.I.; Stoenner, H.G.; Frank, S.A. Pathogen escape from host immunity by a genome program for antigenic variation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 18290–18295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dworkin, M.S.; Schwan, T.G.; Anderson, D.E., Jr.; Borchardt, S.M. Tick-borne relapsing fever. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 22, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telford, S.R.; Goethert, H.K.; Molloy, P.J.; Berardi, V. Blood smears have poor sensitivity for confirming Borrelia miyamotoi disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 57, e01468-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Cruz, I.; Ramos, C.C.; Taleon, P.; Ramasamy, R.; Shah, J.; Du Cruz, I. Pilot study of immunoblots with recombinant Borrelia burgdorferi antigens for laboratory diagnosis of Lyme disease. Healthcare 2018, 6, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnarelli, L.A.; Anderson, J.F.; Johnson, R.C. Cross-reactivity in serological tests for Lyme disease and other spirochetal infections. J. Infect. Dis. 1987, 156, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, P.-M.; Fehrenbach, F.-J.; Rögler, G.; Pohle, H.D.; Schönberg, A. Relapsing fever and its serological discrimination from Lyme borreliosis. Infection 1992, 20, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, P.J.; Carroll, M.; Fedorova, N.; Brancato, J.; DuMouchel, C.; Akosa, F.; Narasimhan, S.; Fikrig, E.; Lane, R.S. Human Borrelia miyamotoi infection in California: Serodiagnosis is complicated by multiple endemic Borrelia species. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwan, T.G.; Schrumpf, M.E.; Hinnebusch, B.J.; Anderson, D.E., Jr.; Konkel, M.E. GlpQ: An antigen for serological discrimination between relapsing fever and Lyme borreliosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996, 34, 2483–2492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Porcella, S.F.; Raffel, S.J.; Schrumpf, M.E.; Schriefer, M.E.; Dennis, D.T.; Schwan, T.G. Serodiagnosis of louse-borne relapsing fever with glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase (GlpQ) from Borrelia recurrentis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 3561–3571. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lopez, J.E.; Schrumpf, M.E.; Nagarajan, V.; Raffel, S.J.; McCoy, B.N.; Schwan, T.G. A novel surface antigen of relapsing fever spirochetes can discriminate between relapsing fever and Lyme Borreliosis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2010, 17, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J.E.; Wilder, H.K.; Boyle, W.; Drumheller, L.B.; Thornton, J.A.; Willeford, B.; Morgan, T.W.; Varela-Stokes, A. Sequence analysis and serological responses against Borrelia turicatae BipA, a putative species-specific antigen. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovis, K.M.; Schriefer, M.E.; Bahlani, S.; Marconi, R.T. Immunological and molecular analyses of the Borrelia hermsii factor H and factor H-like protein 1 binding protein, FhbA: Demonstration of its utility as a diagnostic marker and epidemiological tool for tick-borne relapsing fever. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 4519–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, M.; Grosskinsky, S.; Brenner, C.; Kraiczy, P.; Wallich, R. Molecular characterization of the interaction of Borrelia parkeri and Borrelia turicatae with human complement regulators. Infect. Immun. 2010, 78, 2199–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röttgerding, F.; Wagemakers, A.; Koetsveld, J.; Fingerle, V.; Kirschfink, M.; Hovius, J.W.; Zipfel, P.F.; Wallich, R.; Kraiczy, P. Immune evasion of Borrelia miyamotoi: CbiA, a novel outer surface protein exhibiting complement binding and inactivating properties. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middelveen, M.J.; Du Cruz, I.; Fesler, M.C.; Stricker, R.B.; Shah, J.S. Detection of tick-borne infection in Morgellons disease patients by serological and molecular techniques. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 11, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, B.A.; Keilp, J.G.; Corbera, K.M.; Petkova, E.; Britton, C.B.; Dwyer, E.; Slavov, I.; Cheng, J.; Dobkin, J.; Nelson, D.R.; et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of repeated IV antibiotic therapy for Lyme encephalopathy. Neurology 2008, 70, 992–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.S.; Cruz, I.D.; Ward, S.; Harris, N.S.; Ramasamy, R. Development of a sensitive PCR-dot blot assay to supplement serological tests for diagnosing Lyme disease. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 37, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shah, J.S.; Du Cruz, I.; Narciso, W.; Lo, W.; Harris, N.S. Improved sensitivity of Lyme disease Western blots prepared with a mixture of Borrelia burgdorferi strains 297 and B31. Chronic Dis. Int. 2014, 1, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Mavin, S.; Milner, R.M.; Evans, R.; Chatterton, J.M.W.; Joss, A.W.L.; Ho-Yen, D.O. The use of local isolates in Western blots improves serological diagnosis of Lyme disease in Scotland. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007, 56, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, J.S.; Liu, S. Species Specific Antigen Sequences for Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever (TBRF) and Methods of Use. U.S. Patent Application No. 15/916,717, 9 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vassarstats. Available online: http://vassarstats.net/index.html (accessed on 9 March 2019).

- National Centre for Biological Information, Bethesda, USA. Available online: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PAGE=Proteins (accessed on 5 March 2019).

- Tracy, K.E.; Baumgarth, N. Borrelia burgdorferi manipulates innate and adaptive immunity to establish persistence in rodent reservoir hosts. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde, J.A. Borrelia burgdorferi keeps moving and carries on: A review of borrelial dissemination and invasion. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapi, E.; Bastian, S.L.; Mpoy, C.M.; Scott, S.; Rattelle, A.; Pabbati, N.; Poruri, A.; Burugu, D.; Theophilus, P.A.S.; Pham, T.V.; et al. Characterization of biofilm formation by Borrelia burgdorferi in vitro. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, R. Molecular basis for immune evasion and pathogenesis in malaria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1998, 1406, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naesens, R.; Vermeiren, S.; Van Schaeren, J.; Jeurissen, A. False positive Lyme serology due to syphilis: Report of 6 cases and review of the literature. Acta Clin. Belg. 2011, 66, 58–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvikar, S.L.; Crowley, J.T.; Sulka, K.B.; Steere, A.C. Autoimmune arthritides, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or peripheral spondyloarthritis following Lyme disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 69, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, R.B.; Perng, G.C. Genetic and antigenic characterization of Borrelia coriaceae, putative agent of epizootic bovine abortion. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1989, 27, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Kalmár, Z.; Cozma, V.; Sprong, H.; Jahfari, S.; D’Amico, G.; Mărcuțan, D.I.; Ionică, A.M.; Magdaş, C.; Modrý, D.; Mihalca, A.D. Transstadial transmission of Borrelia turcica in Hyalomma aegyptium ticks. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0115520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, P.J.; Narasimhan, S.; Wormser, G.P.; Barbour, A.G.; Platonov, A.E.; Brancato, J.; Lepore, T.; Dardick, K.; Mamula, M.; Rollend, L.; et al. Borrelia miyamotoi sensu lato seroreactivity and seroprevalence in the northeastern United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Vigliotti, J.S.; Vigliotti, V.S.; Jones, W.; Shearer, D.M. Detection of Borreliae in archived sera from patients with clinically suspect Lyme disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 4284–4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molloy, P.J.; Telford, S.R.; Chowdri, H.R.; Lepore, T.J.; Gugliotta, J.L.; Weeks, K.E.; Hewins, M.E.; Goethert, H.K.; Berardi, V.P. Borrelia miyamotoi disease in the Northeastern United States: A case series. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 163, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogovskyy, A.; Batool, M.; Gillis, D.C.; Holman, P.J.; Nebogatkin, I.V.; Rogovska, Y.; Rogovskyy, M.S. Diversity of Borrelia spirochetes and other zoonotic agents in ticks from Kyiv, Ukraine. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018, 9, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordstrand, A.; Bunikis, I.; Larsson, C.; Tsogbe, K.; Schwan, T.G.; Nilsson, M.; Bergström, S. Tickborne relapsing fever diagnosis obscured by malaria, Togo. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source | Characteristic | Total No. of Sera |

|---|---|---|

| CDC reference set (n = 50) | Endemic area control | 10 |

| Fibromyalgia | 5 | |

| Mononucleosis | 5 | |

| Multiple sclerosis | 5 | |

| Non-endemic area control | 10 | |

| Periodontitis | 5 | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 5 | |

| Syphilis | 5 | |

| NYB reference set (n = 21) | RPR +ve | 8 |

| Epstein-Barr virus infection | 4 | |

| HIV-1 infection | 4 | |

| Cytomegalovirus infection | 5 | |

| CAP and NYSHD reference set for autoimmunity and allergy (n = 42) | ANA +ve | 2 |

| ANA -ve | 2 | |

| Elevated IgG | 13 | |

| Elevated IgE | 4 | |

| Normal IgE | 2 | |

| Anti-DNA antibody +ve | 2 | |

| RF +ve | 9 | |

| RF -ve | 8 | |

| Columbia University (n = 12) Lyme disease [46] | Clinical Lyme disease and positive by the CDC two-tier test for antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi ss | 12 |

| IGeneX (n = 87) | Bartonella henselae infection | 7 |

| Human granulocytic anaplasmosis | 16 | |

| Babesia microti infection | 14 | |

| Babesia duncani infection | 41 | |

| Human monocytic ehrlichiosis | 5 | |

| Healthy controls | 4 |

| Serum Group | Number of Sera | Sera Scored Positive Only IgM IBs a | Sera Scored Positive Only IgG IBs b | Sera Scored Positive Individually in Both IgM & IgG IBs c | Total Number of Sera Scored Positive in IgM and/or IgG IBs d (%) | Total Number of Sera Scored Positive for Either IgM or IgG Antibodies to Any of the Four Scoring Antigens (%) e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison A | ||||||

| First serum sample from 16 patients who provided two samples | 16 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 9 (56.3%) | 9 (56.3%) |

| First serum sample from the other 35 patients who provided only one sample | 35 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 23 (65.7%) | 27 (77.1%) |

| Total | 51 | 16 | 9 | 7 | 32 (62.7%) | 36 (70.6%) |

| Comparison B | ||||||

| Second serum sample from 16 patients who provided two samples | 16 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 12 (75.0%) | 12 (75.0%) |

| First serum sample from the other 35 patients who provided only one sample | 35 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 23 (65.7%) | 27 (77.1%) |

| Total | 51 | 17 | 9 | 9 | 35 (68.6%) | 39 (76.5%) |

| Parameter | Estimate (95% CI) with Only First Sera | Estimate (95% CI) with Second Sera Where Available |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 70.5% (56.0–82.1) | 76.5% (62.2–86.8) |

| Specificity | 99.5% (97.0–100) | 99.5% (97.0–100) |

| PPV | 97.3% (84.2–99.9) | 97.5% (85.3–99.9) |

| NPV | 93.4% (89.1–96.1) | 94.6% (90.6–97.1) |

| Serum Group | Australia | Ukraine | USA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of sera tested | 100 | 121 | 1158 |

| (i) Only TBRF IB positive | 13 | 4 | 126 |

| (ii) Only LD IB positive | 21 | 20 | 100 |

| (iii) Both LD and TBRF IB positive | 3 | 4 | 76 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shah, J.S.; Liu, S.; Du Cruz, I.; Poruri, A.; Maynard, R.; Shkilna, M.; Korda, M.; Klishch, I.; Zaporozhan, S.; Shtokailo, K.; et al. Line Immunoblot Assay for Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever and Findings in Patient Sera from Australia, Ukraine and the USA. Healthcare 2019, 7, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7040121

Shah JS, Liu S, Du Cruz I, Poruri A, Maynard R, Shkilna M, Korda M, Klishch I, Zaporozhan S, Shtokailo K, et al. Line Immunoblot Assay for Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever and Findings in Patient Sera from Australia, Ukraine and the USA. Healthcare. 2019; 7(4):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7040121

Chicago/Turabian StyleShah, Jyotsna S., Song Liu, Iris Du Cruz, Akhila Poruri, Rajan Maynard, Mariia Shkilna, Mykhaylo Korda, Ivan Klishch, Stepan Zaporozhan, Kateryna Shtokailo, and et al. 2019. "Line Immunoblot Assay for Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever and Findings in Patient Sera from Australia, Ukraine and the USA" Healthcare 7, no. 4: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7040121