Global Scope of Hospital Pharmacy Practice: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

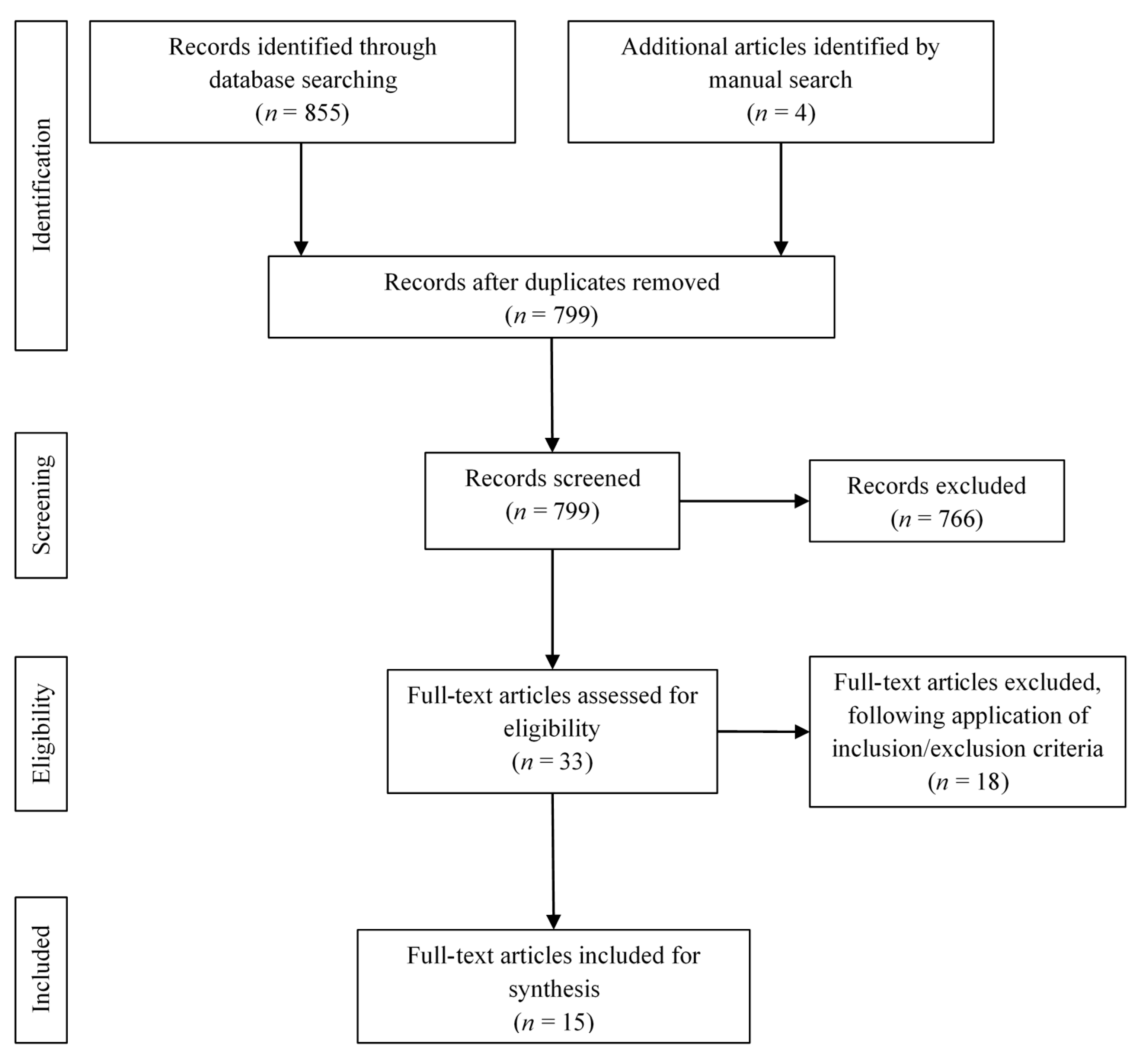

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aim

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Selection and Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Scope of Practice

3.1.1. Pharmaceutical Care Practice

3.1.2. Clinical Pharmacy Practice

3.1.3. Public Health Services

3.2. Multiple Levels of Influence

3.2.1. Individual Factors

3.2.2. Interpersonal Factors

3.2.3. Institutional Factors

3.2.4. Community Factors

3.2.5. Public Policy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holland, R.W.; Nimmo, C.M. Transitions, part 1: Beyond pharmaceutical care. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 1999, 56, 1758–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuyuki, R.T.; Schindel, T.J. Changing pharmacy practice: The leadership challenge. Can. Pharm. J./Revue Pharmaciens Canada 2008, 141, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, C. The need for pharmacy practice research. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2006, 14, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra-Mitjans, M.; Ferrand, É.; Garin, N.; Bussières, J.F. Role and impact of pharmacists in Spain: A scoping review. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2018, 40, 1430–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Clinical Pharmacy. The definition of clinical pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy 2008, 28, 816–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepler, C.D.; Strand, L.M. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm. 1990, 47, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mil, J.F.; Mcelnay, J.; De Jong-Van Den Berg, L.W.; Tromp, F.J. The challenges of defining pharmaceutical care on an international level. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 1999, 7, 202–208. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Social Determinants of Health, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 19–21 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- International Pharmaceutical Federation. The Basel statements on the future of hospital pharmacy. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2009, 66, S61–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SHPA Committee of Specialty Practice in Clinical Pharmacy. Shpa standards of practice for clinical pharmacy. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2005, 35, 122–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontini, R. The european summit on hospital pharmacy. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2014, 21, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pawłowska, I.; Pawłowski, L.; Kocić, I.; Krzyżaniak, N. Clinical and conventional pharmacy services in Polish hospitals: A national survey. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2016, 38, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campbell, G.; Auyeung, V.; McRobbie, D. Clinical pharmacy services in a London hospital, have they changed? Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2013, 35, 688–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyżaniak, N.; Pawłowska, I.; Bajorek, B. The role of the clinical pharmacist in the nicu: A cross-sectional survey of Australian and Polish pharmacy practice. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. Sci. Pract. 2018, 25, E7–E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Baldini Soares, C.; Khalil, H.; Parker, D. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. In Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2017; Available online: https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/ (accessed on 19 October 2019).

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V.; Hayfield, N. Thematic analysis. In Apa Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Langebrake, C.; Ihbe-Heffinger, A.; Leichenberg, K.; Kaden, S.; Kunkel, M.; Lueb, M.; Hilgarth, H.; Hohmann, C. Nationwide evaluation of day-to-day clinical pharmacists’ interventions in German hospitals. Pharmacotherapy 2015, 35, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Hajj, M.S.; Al-saeed, H.S.; Khaja, M. Qatar pharmacists’ understanding, attitudes, practice and perceived barriers related to providing pharmaceutical care. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2016, 38, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoue, M.G.; Al-Taweel, D. Role of the pharmacist in parenteral nutrition therapy: Challenges and opportunities to implement pharmaceutical care in Kuwait. Pharm. Pract. 2016, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lemay, J.; Waheedi, M.; Al-Taweel, D.; Bayoud, T.; Moreau, P. Clinical pharmacy in Kuwait: Services provided, perceptions and barriers. Saudi Pharm. J. 2018, 26, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, H.T.; Nguyen, H.T.; Pham, V.T.; Ba, H.L.; Dong, P.T.; Cao, T.T.; Nguyen, H.T.; Brien, J.A. Hospital clinical pharmacy services in Vietnam. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2018, 40, 1144–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messerli, M.; Maes, K.A.; Hersberger, K.E.; Lampert, M.L. Mapping clinical pharmacy practice in Swiss hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. Sci. Pract. 2016, 23, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owenby, R.K.; Brown, J.N.; Kemp, D.W. Evaluation of pharmacy services in emergency departments of veterans affairs medical centers. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2015, 72, S110–S114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holle, L.M.; Harris, C.S.; Chan, A.; Fahrenbruch, R.J.; Labdi, B.A.; Mohs, J.E.; Norris, L.B.; Perkins, J.; Vela, C.M. Pharmacists’ roles in oncology pharmacy services: Results of a global survey. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2017, 23, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penm, J.; Chaar, B.; Moles, R. Hospital pharmacy services in the Pacific Island Countries. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2015, 21, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penm, J.; Chaar, B.; Moles, R. Clinical pharmacy services that influence prescribing in the Western Pacific region based on the Fip Basel Statements. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2015, 37, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Tameemi, N.K.; Sarriff, A. Knowledge, attitude and practice of pharmacists on medication therapy management: A survey in hospital Pulau Pinang, Penang, Malaysia. J. Pharm. Health Care Sci. 2019, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, D.M.; Strand, M.; Undem, T.; Anderson, G.; Clarens, A.; Liu, X. Assessment of pharmacists’ delivery of public health services in rural and urban areas in Iowa and North Dakota. Pharm. Pract. 2016, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Strand, M.A.; Scott, D.M.; Undem, T.; Anderson, G.; Clarens, A.; Liu, X. Pharmacist contributions to the ten essential services of public health in three national association of boards of pharmacy regions. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2017, 57, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimer, B.K.; Glanz, K. Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice; US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fathelrahman, A.; Ibrahim, M.; Wertheimer, A. Pharmacy Practice in Developing Countries: Achievements and Challenges; Academic Press: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Benchmarking and Hospital Pharmacy: Pharmacy Focus. Available online: http://www.apha.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Pharmacy-Focus.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Wiedenmayer, K.; Summers, R.S.; Mackie, C.A.; Gous, A.G.; Everard, M.; Tromp, D.; World Health Organization. Developing Pharmacy Practice: A Focus on Patient Care: Handbook; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc, J.M.; Dasta, J.F. Scope of international hospital pharmacy practice. Ann. Pharm. 2005, 39, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Equity. Available online: https://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/equity/en/ (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Leotsakos, A.; Zheng, H.; Croteau, R.; Loeb, J.M.; Sherman, H.; Hoffman, C.; Morganstein, L.; O’Leary, D.; Bruneau, C.; Lee, P.; et al. Standardization in patient safety: The Who High 5s Project. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2014, 26, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Author, Year | Country | Design and Objective | Sample (n) | Methodology | Core Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Hajj et al., 2016 [18] | Qatar | Quantitative Describe the practice of PC and explore the challenges to its implementation and evaluate pharmacists’ level of understanding of PC and their attitudes towards the practice. | Pharmacists (274) | Cross-sectional survey. | The majority of the pharmacists had an accurate understanding of the aim and their role in PC. However, less than half knew the role of the patient in PC. Not much time was spent on PC activities. The main challenges reported included a lack of accessibility to patient medical information, staff, and time. | Low response rate, non-respondent bias, social desirability bias. |

| Krzyzaniak et al., 2018 [14] | Australia, Poland | Quantitative Describe and compare the pharmacy services performed in NICUs in Australia versus Poland. | Pharmacists (52) | Cross-sectional online survey. | A higher percentage of clinical services were offered in Australia compared to Poland, including drug recommendations, drug therapy problems interventions, and patient medication chart review. | The sample may not be representative of both countries. |

| Katoue & Al-Taweel, 2016 [19] | Kuwait | Qualitative Explore the therapeutic role of pharmacists in PN, their information sources, their thoughts on NSTs, challenges to PC practice, and opinions on its enhancement. | TPN pharmacists (7) | Semi-structured interviews. | Pharmacists were mainly involved with technical tasks with minimal patient care. Despite preferring to work within NSTs, no hospital had any functioning teams. The reported challenges included a lack of reliable information sources, lack of SOPs, staff, and time limitations, as well as poor communication. | Small sample size, social desirability bias. |

| Pawłowska et al., 2016 [12] | Poland | Quantitative Explore the implementation of both clinical and traditional pharmacy practice in Polish general hospitals. | Head pharmacists (166) | Cross-sectional survey | Most participants were involved in drug procurement and circulation, compounding, monitoring ADR, and drug management services. Only 7% were involved with patients and 4% did ward rounds. The main challenge reported was the lack of precise hospital pharmacy practice legal regulations. | Potential misinterpretation of the survey questions. |

| Lemay et al., 2018 [20] | Kuwait | Quantitative Document existing CPSs, identify challenges to their implementation, and evaluate pharmacists’ perceptions on the future CPSs across public hospitals. | Pharmacists (166), Physicians (284) | Cross-sectional survey. | More than 50% of the pharmacists provided CPSs mainly related to providing education and drug information. The majority were not sure about the future extension of the breadth of their services. A total of 97% of physicians were positive about the clinical role of the pharmacist. Major reported challenges included a lack of policy, time, and clinical skills. | Limited to governmental hospitals. |

| Trinh et al., 2018 [21] | Vietnam | Mixed methods Explore the CPSs as well as the facilitators and challenges in implementing them in Hanoi hospitals. | Quantitative: Head/deputy head pharmacists (39)Qualitative: Pharmacists (20) | Cross-sectional online survey and in-depth interviews. | The majority of the CPSs were nonpatient-specific, including providing drug information, ADR reporting, and monitoring of drug usage. Reported barriers included a dearth of workforce and competent clinical pharmacists. | Small sample for the interviews; the study involved one province only. |

| Messerli et al., 2016 [22] | Switzerland | Quantitative To map the provision of CPSs and to discuss their development process. | Pharmacists (47) | Cross-sectional survey. | The majority of the hospitals offered CPS. A total of 73% involved weekly multidisciplinary ward rounds and 9.1% performed medication reconciliation daily. | Services reported based on local needs. |

| Owenby et al., 2015 [23] | United States | Quantitative Determine the prevalence and the types of pharmacy services and the attitude towards future pharmacy services in Veteran Affairs Emergency Departments. | Pharmacists (33) | Cross-sectional online survey. | The core pharmacy services implemented included medication reconciliation, educating/counseling patients, recommending pharmacotherapy, educating healthcare professionals, precepting activities, reporting ADR, and maintaining compliance with the formulary. | Low response rate of 21.6% and possible selection bias. |

| Holle et al., 2017 [24] | United States | Quantitative Identify pharmacy services in the field of oral chemotherapy programs, MTM, and CPAs. | ACCP and Hematology/Oncology PRN Pharmacists (81) | Cross-sectional survey. | A total of 35% of the respondents provided MTM services, with a small proportion performing quality assurance evaluations. The core CPA activities included medication adjustment, requisition, interpretation, and monitoring lab evaluations, development of therapeutic plans, and patient education. | Low response rate of 10%, restricted to the members of the ACCP and the Hematology/Oncology PRN. |

| J. Penm et al., 2015 [25] | Pacific Island countries | Quantitative Explore hospital pharmacy services as well as hospital pharmacists’ effect on medication prescriptions and quality use of medicines. | Head pharmacists (55) | Cross-sectional online survey. | More than half of the hospitals had CPSs with an average of two pharmacists onboard. The majority had a formulary, as well as a Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee. Participants also believed they had a good relationship with other HCP and good communication skills as well as took professional responsibility for the prescribed medications. | Low response rate and missing data. |

| Jonathan Penm et al., 2015 [26] | Western Pacific region | Quantitative Explore the implementation of CPSs that influence prescribing and the facilitators and challenges of their practice. | Head pharmacists (726) | Cross-sectional online survey | A total of 90.6% of the hospitals reported providing CPSs, with an average of 28% pharmacists performing regular medical rounds. A total of 30% of the inpatients receive medication reconciliation and discharge counselling. Facilitating factors include government sustenance, physician, and patient prospects. | Selection bias, non-response bias, low response rate of 29%, item non-response. |

| Langebrake et al., 2015 [17] | Germany | Quantitative Describe and evaluate the extent of pharmacists’ interventions in the ADKA-DokuPIK database. | Pharmacist interventions (27610) | Retrospective descriptive analysis. | The rate of implementation of the PIs was 85.5%. It mainly involved dose change, drug change, and drug suspension. | No successive documentation of all pharmacists’ interventions. |

| Al-Tameemi & Sarriff, 2019 [27] | Malaysia | Quantitative Assess the KAP of pharmacists at Hospital Pulau, Pinang on MTM services, identify the barriers towards the future provision of such services. | Pharmacists (93) | Cross-sectional survey. | Most of the respondents had a high level of knowledge of MTM. All agreed it could enhance the quality of health care and the majority were keen on providing such services. The potential barriers included lack of training (88.2%), budget (51.6%), and time (46.2%). | Small study only one hospital involved. |

| Scott et al., 2016 [28] | United States | Quantitative Assess the frequency of public health and essential services delivery and barriers to their expansion among rural and urban Iowa and North Dakota pharmacists. | Pharmacists (602) | Cross-sectional online survey. | Pharmacists in rural areas reported a higher frequency of delivery of public and essential services including MTM, immunizations, tobacco counselling, drug disposal programs, evaluation of pharmacy service provision, partnership with the community on health problems, and assessment of community health risks. | Low response rate; a small study involving two states. |

| Strand et al., 2017 [29] | United States, Canada | Quantitative Determine and compare pharmacists’ views of their involvement in the 10 essential public health services in Iowa, North Dakota, and Manitoba. | Pharmacists (649) | Cross-sectional online survey. | The main practised services included the enforcement of health and safety protection laws and regulations, public counselling on health issues, and participation in training. | Recall bias, non-response bias, low response rate. |

| Main Themes | Specific Aspects | Sources | Sample Quotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scope of practice | Pharmaceutical care | [14,18,19] | “We only receive the TPN orders and compound the TPN bags. We don’t see the patients” [15]. “Nursing staff have become reliant on medication guidelines and are hesitant to work outside of these guidelines without pharmacy involvement” [11]. |

| Clinical pharmacy | [12,17,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] | “Clinical pharmacists only pool the needs of clinical wards then submit it to PTC. [They] are not involved in process to add or remove medicines in the hospital formulary” [21]. “Collaboration is only associated with the preparation of drugs for the ward, formulations for individual patients such as powders, feeding bags or antibiotics… contact with doctors is very limited. The most common contact is with the NUM” [11]. “The common tasks of clinical pharmacists in clinical wards are checking the indications and contraindications, evaluating the drug choice, dosage…discussing the intervention with doctors” [21]. | |

| Public health | [21,28,29] | “Clinical pharmacists receive ADR reports which was reported directly from clinical wards or [clinical pharmacists] check ADR logbooks in clinical wards during weekly hospital investigations. Next [clinical pharmacists] enquire about missed information and write the report, then send to the National Drug Information and ADR Monitoring Centre” [21]. | |

| Multiple levels of influence | Individual factors | [12,14,18,19,20,21,25,27,28,30] | “I would like to provide pharmaceutical care but simply I do not know where or how to start, and I am not comfortable with taking risks associated with assuming responsibility for the treatment outcomes of patient” [17]. “Our background knowledge regarding TPN from our undergraduate study is limited and the type of work we are involved in is critical. We need more training” [15]. |

| Interpersonal factors | [18,19,22,25] | “The physicians believe that PN therapy is their own responsibility. They take over all the decisions related to TPN [15].” “Great multidisciplinary team-work. The NICU pharmacist is an integral part of the team. Effective rapport and communication between medical staff, nursing staff and pharmacist. Regular consultation for pharmacist input during medical rounds, and throughoutthe day” [11]. “Doctors haven’t been familiar with clinical pharmacists’ interventions yet. HCPs at clinical wards are still afraid [of pharmacists] because for a long time ago, pharmacists used to come to clinical wards to check the medication boxes. So [we] really want to change the attitude of other HCPs” [21]. | |

| Institutional factors | [12,18,19,20,21,22,24,26,27,28,29] | “I think the absence of this team is due to organizational issues, e.g., lack of guidelines to develop NSTs at hospitals. In addition, there may be insufficient staff to establish NST” [15]. | |

| Community factors | [21,26,28] | “Clinical case discussions are regular; sometimes take place in grand rounds at our hospital. Identified medication errors are more likely accepted by physicians when the director and head of the administration department were there…” [21]. | |

| Public policy | [19,20,26] | “Unfortunately, we don’t have any continuing medical education (CME) activities related to TPN in Kuwait” [15]. “We don’t have a standard reference for our work. Each hospital has its own TPN protocol which is different from one hospital to another. This can create communication problems among the hospitals” [15]. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmed Abousheishaa, A.; Hatim Sulaiman, A.; Zaman Huri, H.; Zaini, S.; Adha Othman, N.; bin Aladdin, Z.; Chong Guan, N. Global Scope of Hospital Pharmacy Practice: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2020, 8, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020143

Ahmed Abousheishaa A, Hatim Sulaiman A, Zaman Huri H, Zaini S, Adha Othman N, bin Aladdin Z, Chong Guan N. Global Scope of Hospital Pharmacy Practice: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2020; 8(2):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020143

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmed Abousheishaa, Aya, Ahmad Hatim Sulaiman, Hasniza Zaman Huri, Syahrir Zaini, Nurul Adha Othman, Zulhilmi bin Aladdin, and Ng Chong Guan. 2020. "Global Scope of Hospital Pharmacy Practice: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 8, no. 2: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020143

APA StyleAhmed Abousheishaa, A., Hatim Sulaiman, A., Zaman Huri, H., Zaini, S., Adha Othman, N., bin Aladdin, Z., & Chong Guan, N. (2020). Global Scope of Hospital Pharmacy Practice: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 8(2), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020143