Novel Insight into How Nurses Working at PH Specialist Clinics in Sweden Perceive Their Work

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Study Setting and Population

2.3. Data Collection

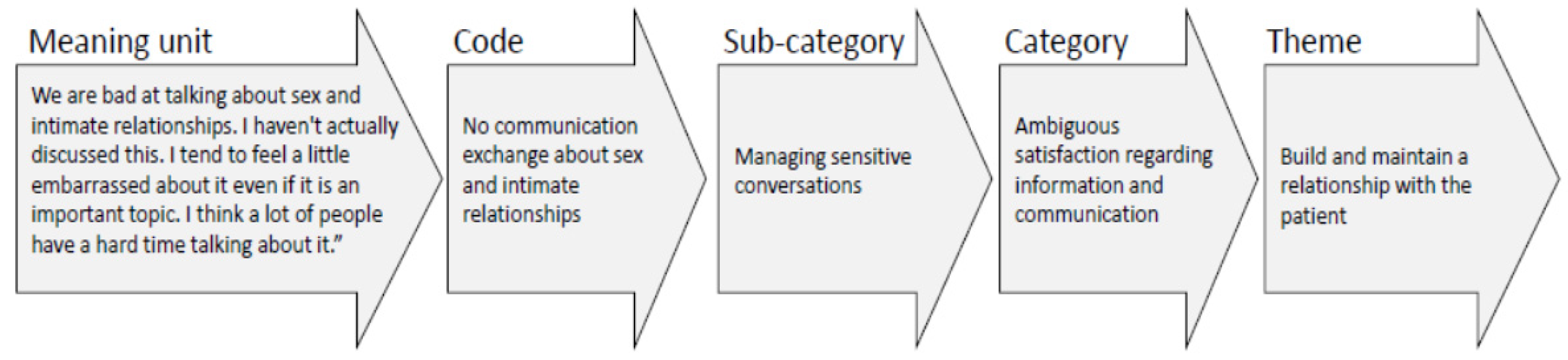

2.4. Data Analysis

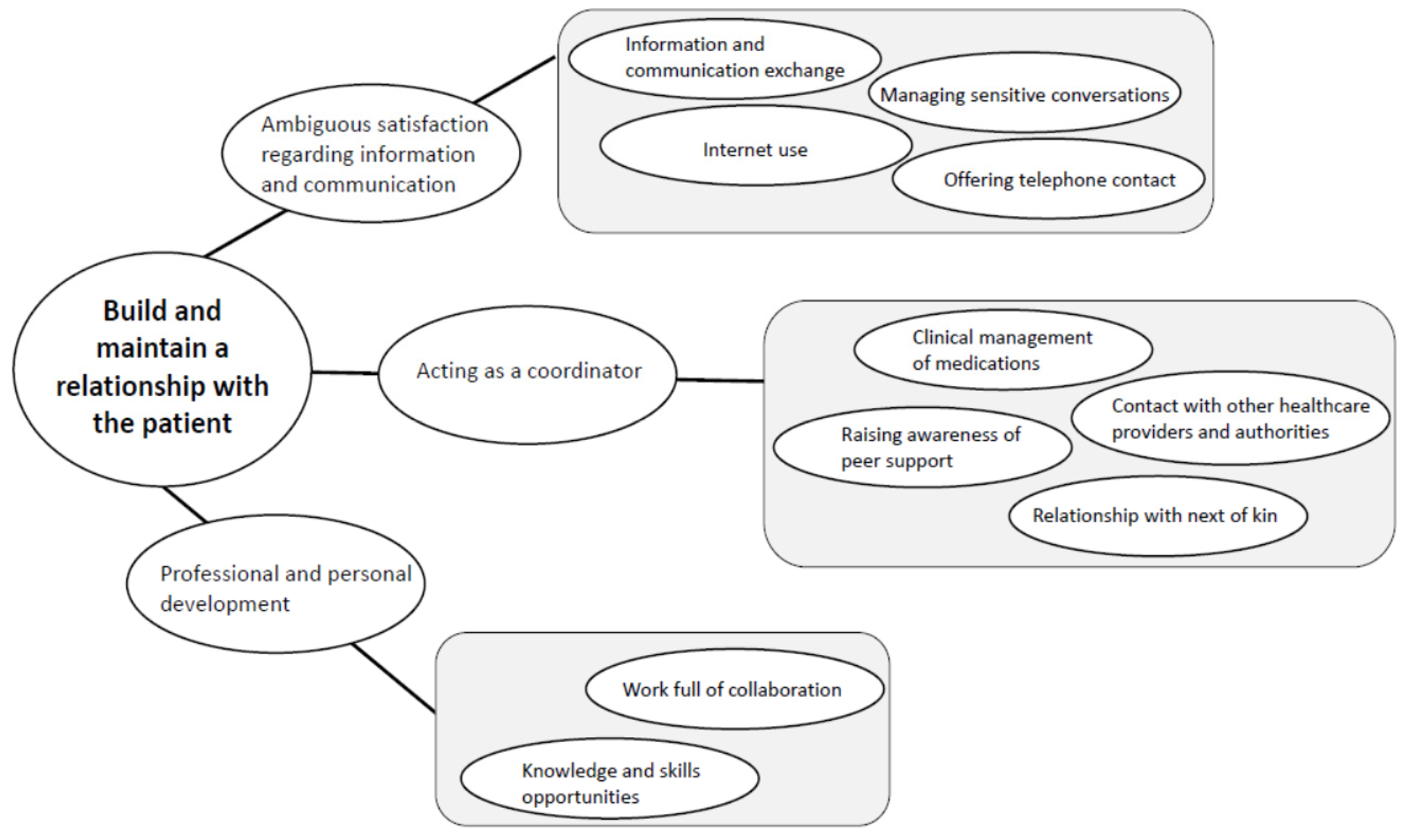

3. Findings

3.1. Ambiguous Satisfaction Regarding Information and Communication

3.1.1. Information and Communication Exchange

“For every patient, I find that you have to tailor the information a little and get a sense of what they can take in.”(12)

3.1.2. Managing Sensitive Conversations

“We are bad at talking about sex and intimate relationships. I haven’t actually discussed this. I tend to feel a little embarrassed about it even if it is an important topic. I think a lot of people have a hard time talking about it.”(6)

3.1.3. Internet Use

“Patients can misinterpret numbers and figures on death statistics… and some patients have been truly devastated to read this information, so it is really beneficial that they can come to us and get the right information”(7)

3.1.4. Offering Telephone Contact

“I try to make follow-up calls with patients frequently but still, over the phone isn’t always the best way, sometimes you just need to sit down and talk face-to-face...”(12)

3.2. Acting As a Coordinator

3.2.1. Clinical Management of Medications

“We tend to be a little mean and tell the patient that we will be happy if they get side effects...it kind of gives the impression that the medicine is working, to make the patients understand that it is nothing to be afraid of.”(7)

3.2.2. Contact with Other Healthcare Providers and Authorities

“It is quite a lot of work required from us and the medical team behind the PH patients in talking to physicians, making clarifications, writing new medical certificates, and explaining everything more clearly once more. So, yes, it’s an unnecessary energy thief for us and unnecessary worry and strain for this patient group.”(1)

3.2.3. Relationship with Next of Kin

“We really try to see the relatives as a resource… it is good to share, but in order for a family member to be able to understand things properly, they need to have knowledge of what this is all about and the goals we have in terms of treatment of the illness.”(1)

3.2.4. Raising Awareness of Peer Support

“When it’s been a while, we usually advise our patients to talk to another patient in their own age… We know a lot about the disease, but we haven’t had it ourselves. A fellow patient can explain that in a good, and better way.”(2)

3.3. Professional and Personal Development

3.3.1. Work Full of Collaborations

“We have a PH team meeting, where the physicians can raise issues if they are hesitant about how to proceed and discuss treatment options. There are cases that are difficult and where you have back-and-forth discussions. It is very educational, and the physicians appreciate getting feedback... it is simply a very good learning opportunity”(13)

3.3.2. Knowledge and Skills Opportunities

“…the Swedish Association for Pulmonary Hypertension network meeting for the nurses is very important... but I would like more possibilities for education, PH is truly a serious and complex disease.”(10)

4. Discussion

Methodological Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- SPAHR—The Swedish PAH Registry. 2018. Available online: http://www.ucr.uu.se/spahr/ (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Yorke, J.; Armstrong, I.; Bundock, S. Impact of living with pulmonary hypertension: A qualitative exploration. Nurs. Health Sci. 2014, 16, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivarsson, B.; Ekmehag, B.; Sjöberg, T. Information Experiences and Needs in Patients with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension or Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension. Nurs. Res. Pr. 2014, 2014, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivarsson, B.; Ekmehag, B.; Sjöberg, T. Support Experienced by Patients Living with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension. Hear. Lung Circ. 2016, 25, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitbon, O.; Gomberg-Maitland, M.; Granton, J.; Lewis, M.I.; Mathai, S.C.; Rainisio, M.; Stockbridge, N.L.; Wilkins, M.R.; Zamanian, R.T.; Rubin, L.J. Clinical trial design and new therapies for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1801908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGoon, M.D.; Ferrari, P.; Armstrong, I.; Denis, M.; Howard, L.S.; Lowe, G.; Mehta, S.; Murakami, N.; Wong, B.A. The importance of patient perspectives in pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1801919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillevin, L.; Armstrong, I.; Aldrighetti, R.; Howard, L.S.; Ryftenius, H.; Fischer, A.; Lombardi, S.; Studer, S.; Ferrari, P. Understanding the impact of pulmonary arterial hypertension on patient’s and carer’s lives. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2013, 22, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galiè, N.; Humbert, M.; Vachiéry, J.-L.; Gibbs, S.; Lang, I.M.; Kamiński, K.A.; Simonneau, G.; Peacock, A.; Noordegraaf, A.V.; Beghetti, M.; et al. ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Hear. J. 2015, 37, 67–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivarsson, I.B.A.; Ryftenius, H.; Landenfelt-Gestre, L.-L.; Kjellström, B. EXPRESS: Outpatient specialist clinics for pulmonary arterial hypertension and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension in the Nordic countries. Pulm. Circ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivarsson, B.; Sjöberg, T.; Hesselstrand, R.; Rådegran, G.; Kjellström, B. Everyday life experiences of spouses of patients who suffer from pulmonary arterial hypertension or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. ERJ Open Res. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gin-Sing, W. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: A multidisciplinary approach to care. Nurs. Stand. 2010, 24, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S. Pulmonary Hypertension Patient Navigation: Avoiding the Perfect Storm. Adv. Pulm. Hypertens. 2016, 15, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noël, P.H.; Frueh, B.C.; Larme, A.C.; Pugh, J.A. Collaborative care needs and preferences of primary care patients with multimorbidity. Health Expect. 2005, 8, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohsfield, R.; Archer-Chicko, C.; Housten, T.; Nolley, S.H. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Emergency Complications and Evaluation. Adv. Emerg. Nurs. J. 2018, 40, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- la Pelle, N. Simplifying Qualitative Data Analysis Using General Purpose Software Tools. Field Methods 2004, 16, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, S.C.; Clark, R.A.; Dierckx, R.; Prieto-Merino, D.; Cleland, J.G. Structured telephone support or non-invasive telemonitoring for patients with heart failure. BMJ Heart 2017, 103, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matura, L.A.; McDonough, A.; Aglietti, L.M.; Herzog, J.L.; Gallant, K.A. A Virtual Community. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2012, 22, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graarup, J.; Ferrari, P.; Howard, L.S. Patient engagement and self-management in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2016, 25, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, W.G.; Kools, S.; Lyndon, A. Dancing Around Death. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 23, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronenwett, L.; Sherwood, G.; Barnsteiner, J.; Disch, J.; Johnson, J.; Mitchell, P.; Sullivan, D.T.; Warren, J. Quality, and safety education for nurses. Nurs. Outlook 2007, 55, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, V.V.; Shah, S.J.; Souza, R.; Humbert, M. Management of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 1976–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grady, D.; Weiss, M.; Hernandez-Sanchez, J.; Pepke-Zaba, J. Medication and patient factors associated with adherence to pulmonary hypertension targeted therapies. Pulm. Circ. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivarsson, B.; Hesselstrand, R.; Rådegran, G.; Kjellström, B. Adherence and medication belief in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: A nationwide population-based cohort survey. Clin. Respir. J. 2018, 12, 2029–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, S.; Xie, W.; Wan, J.; Kuang, T.; Yang, Y.; Huang, H.; Wang, C. The impact and financial burden of pulmonary arterial hypertension on patients and caregivers. Medicine 2017, 96, e6783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Board of Health and Welfare. Available online: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik-och-data/statistik/statistikamnen/halso-och-sjukvardspersonal (accessed on 12 June 2020).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ivarsson, B.; Kjellström, B. Novel Insight into How Nurses Working at PH Specialist Clinics in Sweden Perceive Their Work. Healthcare 2020, 8, 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020180

Ivarsson B, Kjellström B. Novel Insight into How Nurses Working at PH Specialist Clinics in Sweden Perceive Their Work. Healthcare. 2020; 8(2):180. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020180

Chicago/Turabian StyleIvarsson, Bodil, and Barbro Kjellström. 2020. "Novel Insight into How Nurses Working at PH Specialist Clinics in Sweden Perceive Their Work" Healthcare 8, no. 2: 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020180

APA StyleIvarsson, B., & Kjellström, B. (2020). Novel Insight into How Nurses Working at PH Specialist Clinics in Sweden Perceive Their Work. Healthcare, 8(2), 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020180