1. Introduction

Inadequate knowledge about nutrition and physical activity causes bad habits in young people. Teenagers are spending a lot of hours in sedentary activities, practicing a low level of physical activity [

1,

2]. Consequently, one of the most significant health problems related to the teenagers is the obesity [

3,

4,

5]. Studies identified a relationship between teenagers’ poor habits to socioeconomic factors [

6] and energy intake [

5].

Obesity is defined as a chronic, complex, and multifactorial disease that is unfavorable for health. It is characterized by an excessive increase in body fat, resulting from the imbalance of caloric expenditure and energy intake [

7]. This imbalance is favorable to the development of several metabolic complications, namely insulin resistance, which leads to hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, hypertriglyceridemia, low levels of high-density lipoprotein, and hypertension [

8]. The best way to spend calories is through physical activity, which better influences energy balance and weight control [

9].

The reduction and control of the incidence and prevalence of overweight and obesity in the child and school population is one of the goals proposed for 2020 in the National Health Plan—Review and Extension to 2020 [

10]. Thus, in Portugal, the General Directorate of Health, created the National Program for the Promotion of Healthy Eating, in which public health strategies for combating obesity are addressed and created. Since 2017, information on the levels of physical activity and physical inactivity of users of the National Health Service has been gathered [

11].

For children, adolescents and young adults aged between 5 and 19 years, the World Health Organization (WHO) defines excess weight as the Body Mass Index (BMI) for age with more than a typical deviation above the median established in child growth patterns and obesity as being higher than two standard deviations above the norm established in child growth patterns [

7]. Thus, children, adolescents, and young adults aged 13 to 19 years between the 85th and 95th percentile are overweight and above the 95th percentile are classified as obese children [

12]. In recent years, there has been an increase in obesity among children, adolescents, and young adults in many countries, and its fight has been the target of several measures in the field of public health [

13]. According to the WHO, in 2016, the number of children, adolescents, and young adults (5–19 years), where overweight or obese teenagers exceeded 340 million [

7].

As an attempt to tackle this obesity problem, the aim of this study consists in using a mobile application for the promotion of healthy physical activity and nutrition habits to teenagers. The target population needs several mechanisms to stimulate physical activity, including gamification, medical control, and personalized advices. In particular, with the gamification approach, we attempt to apply typical elements of game playing (e.g., point scoring, competition with others, rules of play) to the healthy nutrition and physical activity, to encourage engagement with the mobile application.

The scope of this project includes teenagers from two public schools of the municipalities of Fundão and Covilhã (center of Portugal), where the teenagers used a mobile application for five weeks with the different functionalities proposed at [

14]. After this time, the teenagers answered a questionnaire related to satisfaction with the use of the mobile application. This paper analyses the evolution of the physical activity and nutrition habits of the teenagers involved in the study with a mobile application.

This remainder of the article is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents the related work based on the analysis of the world’s obesity, mobile applications related to nutrition and physical activity available in the Google Play store, and studies with similar our project methodology with teenagers. The methods implemented are presented in

Section 3, showing the results of this study in

Section 4. This paper reports the discussion in

Section 5, concluding this paper with the conclusions in

Section 6.

2. Related Work

The study [

15], published in 2018, presents data collected between 2015 and 2016 in Portugal, concluding that the prevalence of obesity increases with increasing age, being less prevalent in children and higher in the elderly. There are three critical periods in life-related to the prevalence of obesity, namely at 5 years old, 15 years old, and finally, 75 years old. This study revealed that approximately 17.3% of children (aged less than 10 years old) have pre-obesity and 23.6% of adolescents, aged between 10 and 18 have pre-obesity (i.e., overweight). Also, 7.7% of children, as well as 8.7% of adolescents, were obese [

16,

17].

According to studies carried out in Europe, adolescents in Europe consume high amounts of fast food and sugary drinks, and spend less time on family meals compared to previous generations [

18]. In adolescence, healthy eating is being put aside, decreasing the consumption of fruits and vegetables, and increasing the consumption of sweets and soft drinks. They consume half the recommended amount of fruits and vegetables and less than two-thirds of the recommended amount of milk and dairy products, consuming more meat, fats and sweets than recommended [

18].

Regarding physical activity among young people in Europe, the levels are generally deficient, being even lower among young women and decreasing as they progress through adolescence [

9], sedentary behaviors dominated the daily lives of adolescents [

19], reaching 60% of the regular time of young people spent in this type of activities [

20], about nine waking hours [

18]. Around 11 and 13 years old, there is a more marked increase in this type of behavior [

21].

One of the significant problems of childhood obesity is reflected by data on the prevalence of physical activity in Portugal, collected between 2015 and 2017, which estimate that only about half of children reach WHO recommendations [

11]. Some data suggest that recommendations for physical activity are not met in three-quarters of the Portuguese population over 15 years old [

22].

A study carried out in 2017 by the WHO [

23], estimated that as the adolescents are older, the level of physical activity decreases, based on analyzing the answers to the question regarding doing “at least one hour of moderate to vigorous activity every day”, it was answered positively by 25% of children aged with 11 years old. Still, for those aged with 15 years old, the number drops to 16%. In this study, we also conclude that the older adolescents are more likely to have sedentary behaviors. Other studies support this and also suggest that even more complex patterns are present [

24]. With children aged with 11 years old, only 50% report watching two or more hours of television during the week, against 63% of those who are older [

23]. The study [

9] reports the converse, registering a decrease in obesity in individuals aged with 11, 13, and 15 years old with increasing age.

Other works address a similar problem, but about physical inactivity of adults in Sweden, such as [

25]. The design of the study is similar, and also similarly to our work, where we monitor the participants for 5 weeks, in this study, participants were monitored for 4 weeks.

Based on the research of the strategies implemented to encourage the use of this type of mobile applications by young people, we found that it is necessary to innovate regularly with different ideas, requiring an interactive design, ease of use, frequent updating of information, use of questionnaires as interaction with young people, use of gamification and promoting benefits from using the application [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

4. Results

4.1. Results of the Participation in the Study

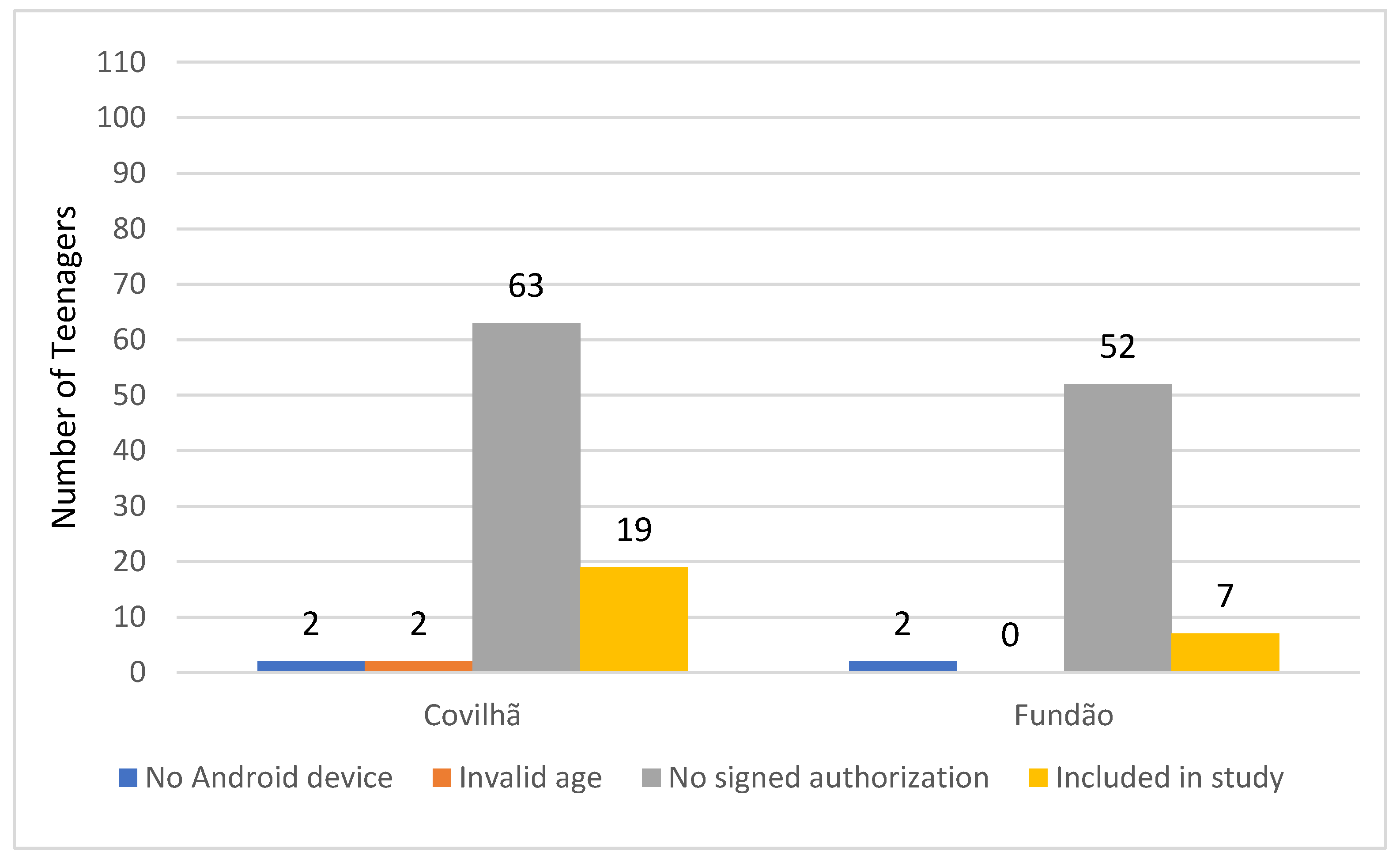

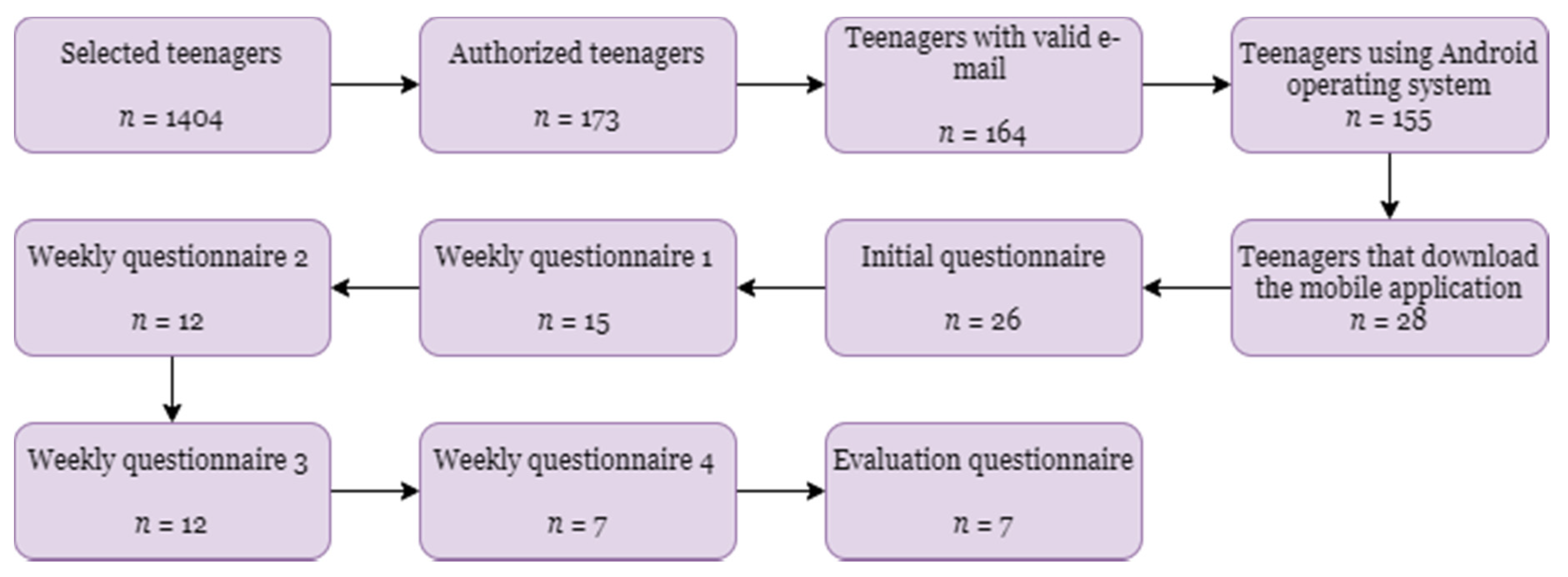

At the beginning of the study, as presented in

Figure 2, 1404 teenagers from two schools placed in Fundão and Covilhã (Portugal) municipalities were selected. Of those selected, only 173 teenagers were authorized by the parents to participate in the study. Next, only 164 teenagers provided a valid email to send the invitation for the participation in the study. Of those with valid emails, only 155 teenagers reported that they have a smartphone with Android operating system. Between them, only 28 students downloaded and installed the mobile application.

The study started on 21 February 2020, and 26 teenagers filled in the initial questionnaire. At that moment, the dispersion of the pandemic situation increased, and the teenagers could not be in physical contact with others. Thus, at the first weekly questionnaire, only 15 teenagers answered the questions. In comparison, weekly questionnaire 2 reduced the number of answers to 12 teenagers. This number maintained between the weekly questionnaire 2 and the weekly questionnaire 3. Unfortunately, the pandemic situation had a very negative impact, and the number of answers reduced to 7 teenagers in the weekly questionnaire 4 and the evaluation questionnaire.

4.2. Sample Analysis

Figure 3 presents the age and BMI distributions. The 16-years-old teenagers are the most present in the study. On the other hand, the average age of the participants is 15-years-old, given the low variability. Between the teenagers aged 13–14 years, 2 teenagers have BMI between 18.5 and 24.9, and 1 teenager has BMI below 18.5. Between the teenagers aged 15–16 years, 3 teenagers have BMI between 18.5 and 24.9, and 1 teenager has BMI between 25.0 and 29.9.

4.3. Analysis of Population Habits

This subsection describes the student’s habits in relation to physical activities, based on the data of all 26 participants in the study. This information was collected at the beginning of the study. Regarding sports, 71.4% of young people practice sport, but only 43% of young people go to the gymnasium, sports complexes, or swimming pools. Following the frequency of exercising, 42.9% of the teenagers are practicing more than three times per week, and 57.1% are practicing less or equals to 3 times per week. Next, following the analysis of the time of exercise, 14.3% of the teenagers are practicing less than 1 h per session, and the remaining 85.7% of the teenagers are practicing more than 1 h per session.

Figure 4 shows the preference for physical activity of the different teenagers, verifying that 42.9% prefers team sports.

Regarding diet, 85.7% of teenagers had no specific diet, where the remaining 14.3% were macrobiotic. Next, 57.1% of teenagers consumed one to two servings of fruit and vegetables per day, and the other 42.9% consumed between three and five servings per day.

Regarding the consumption of sweets, savory snacks, or soft drinks, 57.1% of teenagers said they consume less than three times per week, and the remaining 42.9% consume three or more times per week.

4.4. Analysis of Weekly Questionnaires

For the analysis of weekly questionnaires, each correct answer gave 1 point to the teenagers. Each questionnaire has four questions related to the tips and curiosities shared by the mobile application about nutrition and physical activity during the last week. The level of difficulty of the questions was maintained during the study.

Table 1 shows that the average number of correctly answered questions was higher in weekly questionnaire 3, and the number of correctly answered questions in the first and last questionnaires was the same.

4.5. Results of Feedback

As previously mentioned, at the end of the 5-week period, a satisfaction questionnaire was conducted. Following the results obtained with the satisfaction with the physical monitoring, the students were mainly satisfied, except for one student (14.3%).

After the five weeks of the study, the final questionnaire evaluated the physical activity level of the teenager and 4 of the students (57.1%) kept the level of physical activity on similar level as before the study, and the remaining three students (42.9%) increased it. At the same time, 85.7% of the students were satisfied with the training plan, and only one student (14.3%) was not satisfied. Regarding diet, 5 of the students (71.4%) kept their habits, and the remaining 28.6% claimed that their dietary habits improved.

In respect of the availability of tips and curiosities, 28.6% of the students kept their nutrition and physical activity habits, but the remaining 71.4% improved it. Furthermore, 57.1% considered the tips and curiosities useful. Regarding the weekly questionnaires, 71.4% found it helpful to consolidate the knowledge with tips and curiosities. Regarding the medical follow-up, 71.4% considered it important.

The use of gamification and challenges motivated 71.4% of the participants. The same number of persons that are satisfied with the mobile application said that they would use it in the future (85.7%).

4.6. Global Results of the Mobile Application

Initially, it was found that the inclusion of advertising in the project increases adherence to this type of mobile applications by young people, and the sessions held in selected schools increased the acceptance of the mobile application. Regarding the students that participated in a presentation about the project, i.e., students from Covilhã (Portugal), 23% downloaded the mobile application. Next, related to the students from Fundão (Portugal), where no presentation was made, only 11% downloaded it.

The young people are aged between 13 and 14 years old, and 15 to 16 years. Thus, 42.9% of the young people are aged between 13 and 14 years old, and 57.1% of them are aged between 15 and 16 years old.

For further analysis of the answers related to the consumption of fruit and vegetables, and sweets, savory snacks, and soft drinks,

Table 2 established different points associated with the various answers given. Consequently,

Table 3 shows the ranking of points obtained by different teenagers.

During the study we discovered the existence of teenagers with bad habits that were able to improve. We correlated the different points obtained with the improvement of the teenagers’ diet and found out that two teenagers (28.6%) with bad habits improved as presented in

Table 4. However, we cannot accept that there is a dependency between changing the diet and the points obtained (

. However, most of the teenagers kept the diet.

Table 5 shows the relation between the improvement of final physical activity level with the habits of the teenager. Three teenagers started to perform more physical exercises, and 2 of them improved their frequency. We can confirm that the improvement in the level of physical activity and the frequency of physical activity per week is independent (

As for improving the level of physical activity when compared to the relationship with the duration of each training session, it is possible to conclude that there is no relation between them ( Thus, 6 of the 7 teenagers started practicing more than 1 h of physical exercise, and the level of physical activity of all of them has improved or maintained.

In general, teenagers of different ages are satisfied with the mobile application, as presented in

Table 6. We observed that 6 out of 7 teenagers were satisfied with the mobile application, and we can conclude that their degree of satisfaction is independent of their age (

Finally, based on

Table 7, we verified that the teenagers aged between 13 and 14 were motivated by the mobile application gamification feature. Still, only 50% of the teenagers aged 15 and 16 were motivated by the mobile application gamification feature. However, it was not possible to conclude that the level of motivation depends on the age of teenagers, specialty between 13 and 16 years old (

5. Discussion

Other studies have been performed with teenagers and the use of mobile applications. Considering the different studies found in the literature,

Table 8 shows a comparison of the studies previously analyzed, verifying that three studies revealed a percentage of abandonment lower than the CoviHealth project.

The authors of [

43] verified a reported improvement of the diet. However, the study [

44] did not reveal alterations in the diet of the teenagers. In [

48], the satisfaction was moderate in comparison of the studies with similar methodology. Next, in [

45], the teenagers were satisfied. In conclusion, in [

44], the satisfaction was low. However, compared with our mobile application, most teenagers were confident with the use of mobile applications. Thus, as in the study [

46], the majority of the users of our project would continue with the use of the mobile application.

Some experts do not recommend the use of mobile devices until the age of 14 years old, other experts until the age of 16 years old [

49]. Despite that, this study involves the use of smartphones by 13-year-old adolescents. We do not disagree with these studies, but still, it is a reality that most teenagers, starting from 13 years old or even earlier, use mobile phones. We want to leverage the fact that they have smartphones and put them into good use for obtaining healthy habits.

The healthcare professional has access to all data entered by the teenagers in the mobile application, which allows for close control of the teenagers. Subsequently, data may be validated by the healthcare professional in consultation. All data relating to each teenager can only be entered by him/her or his/her doctor. The measurement of energy expenditure and the pedometer were developed with validated methods [

50,

51,

52,

53].

The study proved that the use of a mobile application simulates the teenagers to have good physical activity and nutrition habits. However, this study has some limitations that may affected the results, such as a low number of teenagers that completed in the study, and the mobile application is only focused in physical activity and nutrition. The teenagers are a special population that are usually captivated by the use of these technologies.

6. Conclusions

The mobile application named CoviHealth was mainly devoted to the education of teenagers about nutrition and physical activity using dynamic tips and curiosities, gamification, challenges, and the possibility to earn points.

The study started with 26 teenagers, but some of the involved students abandoned the study, finalizing the study with the analysis of the participation of seven students. These students are aged between 13 and 16 years old, and they answered a questionnaire about the mobile application. During the study, the students answered four weekly questionnaires about the tips and curiosities provided by the mobile application.

In general, most of the teenagers were satisfied with the mobile application’s different functionalities, including physical activity monitoring, tips and curiosities, and questionnaires. By the end of the study, the teenagers indicated that the medical control would be important, and the use of gamification and challenges promoted the use of the mobile application.

The objective of the study was the promotion of healthy nutrition and physical activity habits, and we verified that the habits of some of the teenagers improved. All the available features in the mobile application were positively rated by the teenagers, saying that they would use it in the future. Still, we verified that the design and functionalities of the mobile application need further improvements. Most notably, medical control should be added to increase the motivation of the teenagers. Nevertheless, the study verified that a mobile application could be a complement for the promotion of healthy lifestyles. Due to the pandemic situation, where the teenagers were lacking close contact with others the number of participants in the study was limited. The conclusions could be improved with the distribution of the mobile application with crowdsourcing which would bring more users and more data.

Finally, after the analysis was carried out, it can be concluded that by implementing questionnaires and the use of gamification, it is possible to attract more young people to use mobile applications to promote healthy nutrition, as well as to adopt good physical activity habits.