Facilitators and Barriers Surrounding the Role of Administration in Employee Job Satisfaction in Long-Term Care Facilities: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction and Background

1.1. Introduction

1.1.1. Rapid Growth of 65+ Population

1.1.2. Residential and Care Needs

1.1.3. Burden on Society and Economics

1.2. Background

1.2.1. Job Satisfaction, Associate Engagement, and Organizational Outcomes

1.2.2. Gap of Research in the Long-Term Care Environment

1.2.3. Cost of Associate Disengagement

1.2.4. Societal and Public Health Crises—Multiplier of Importance of Healthcare Associate Satisfaction

1.3. Significance and Purpose

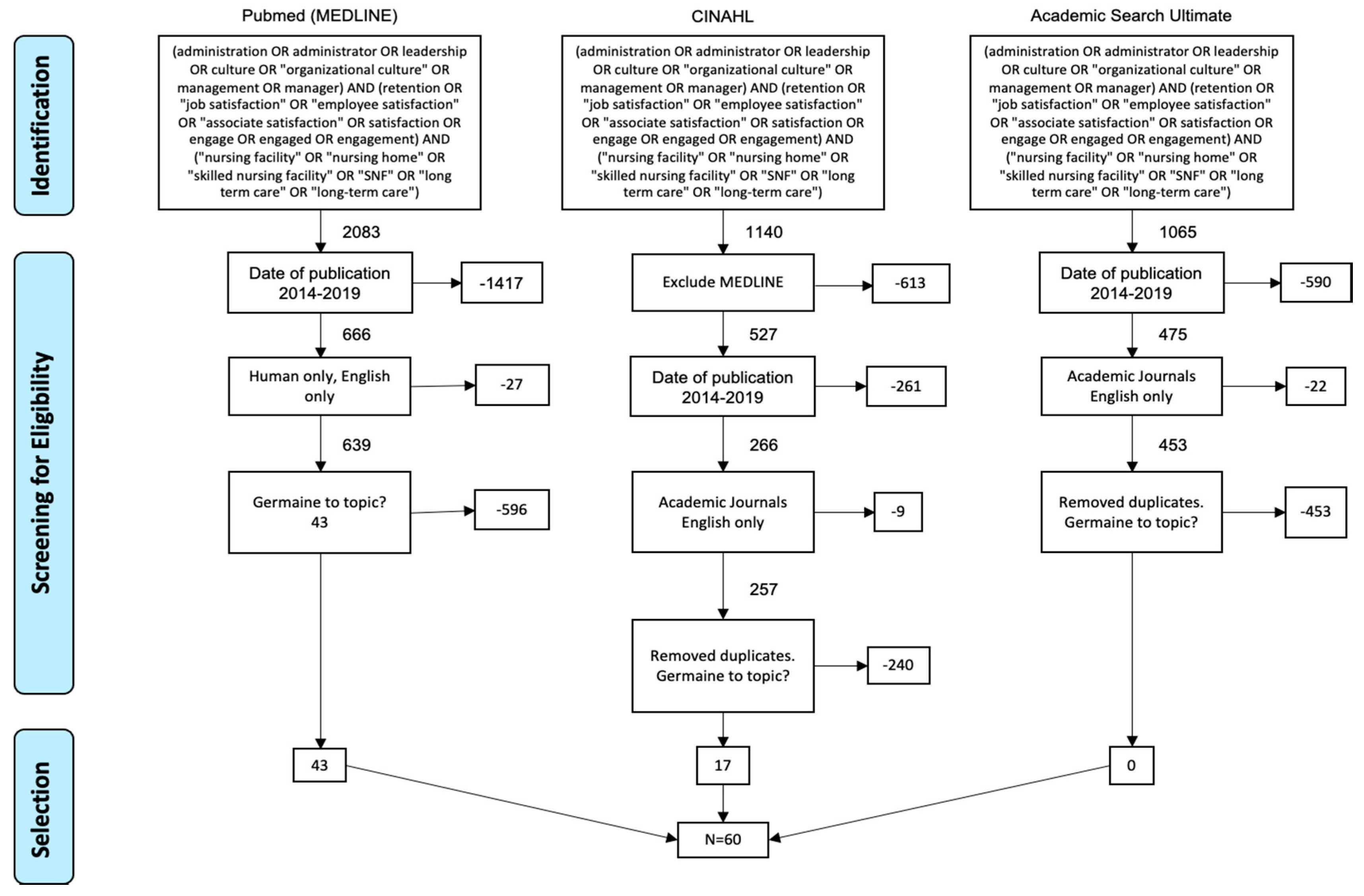

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Most Impactful Themes

4.2. Most Impactful Categories of Themes

4.2.1. Organizational Leadership

4.2.2. Staff Characteristics

4.2.3. Environmental Attributes

4.3. Implications for Future Success in Long-Term Care and in Times of Crisis and Rapid Change

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author Last Name/Year | Objective | Sample/Settings | Study Design and Comparison/Analytical Tool | Key Findings | F/B 1 | Theme |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aloisio/2019 [22] | To identify individual and organizational predictors of job satisfaction of managers in long-term care (LTC) facilities. | 168 managers from 76 LTC homes in three Canadian provinces. | Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Subscale was used to measure job satisfaction. Represented secondary analysis of data from Phase 2 of the Translating Research in Elder Care Programme. | This study identified one individual job satisfaction predictor, high efficacy, and three organizational job satisfaction predictors, social capital, leadership, and adequate orientation. | F | Positive Organizational Values |

| Perreira/2019 [76] | Explore similarities and differences in the work psychology of health service workers employed in LTC and home and community care settings. | 276 LTC employees and 184 home health service employees. | A survey was used to collect data. Path analyses and descriptive statistics were conducted. | This study found that a positive work environment promotes job satisfaction. | F | Enjoyment of Relationships with Patients |

| A low perception of support and tension between facilities and healthcare service workers were found to be barriers to job satisfaction. | B | High Coworker Conflicts | ||||

| Malagon-Aguilera/2019 [23] | To analyze the sense of coherence among RNs 2 and its relationship with health and work engagement. | 109 Nurses working in an LTC setting. | In a cross-sectional study, 109 registered nurses working in an LTC setting responded to a self-administered questionnaire. Multiple linear regression models were used to analyze social support, work-related family conflicts, sense of coherence, self-reported health status, and work engagement variables. | This study found that implementing a program to implement a sense of coherence (SOC) among nurses can contribute to work engagement. A high SOC was associated with adequate socioeconomic level and social support system. Managers providing social support and assigning meaningful tasks contributed to job satisfaction. | F | Positive Organizational Values, Social Support Mechanisms, and Supportive Leadership and Management |

| Escrig-Pinol/2019 [24] | To gain a more refined comprehension of the different dimensions of the charge nurse role as a central figure in the LTCFs 3 analyzed. | 10 RN charge nurses from five LTCFs in Ontario, Canada. | Data were collected via semi-structured interviews. A combination of conventional and direct qualitative content analyses was used. | This study found the charge nurses supervisory skills to directly impact team dynamics and relationships. Professional coaching for charge nurses in LTCFs was found to enhance work–life balance. Recognition for responsibilities increases LTC charge nurse job satisfaction. | F | Supportive Leadership and Management and Positive Organizational Values |

| Undefined charge nurse roles and lack of training were barriers to job satisfaction. | B | Lack of Access to Management, Perception of Focus on Business Aspects Interfering with Care, Lack of Leadership Training, and Lack of Training with Medically complex patients | ||||

| Rajamohan/2019 [75] | To understand the relationship between staff and job satisfaction, stress, turnover, and staff outcomes in PCC NH 4 settings. | Electronic research databases between 2000 and 2015. | Review electronic research databases published between 2000 and 2015. Cohen-Mansfield’s comprehensive occupational stress model was used to analyze the relationship between job satisfaction, stress, turnover, and staff outcomes in PCC NH settings. | This study identified providing patient centered care and integrating the patient centered care philosophy into the mission and vision of the organization to facilitate job satisfaction. | F | Patient-Centered Philosophy |

| Failure to understand patient-centered care philosophy and failure of leadership to support employees in daily activities were barriers to job satisfaction. | B | Lack of Training with Medically Complex Patients, and Perception of Focus on Business Aspects Interfering with Care | ||||

| Jirkovská/2019 [81] | To verify the Effort–Reward Imbalance (ERI) model, which serves as a concept to map workplace stress on professional caregivers. | 265 Czech professionals in 12 facilities providing health and social care services for the elderly. | The verification of the ERI model along with well-being was conducted on the sample. | This article suggests that a barrier of job satisfaction is the challenge of transforming from a traditional care culture to a patient-centered care culture. | B | Business Aspects Interfering with Care |

| Kim/2019 [34] | To examine the efforts of social support, job autonomy, and job satisfaction on burnout among LTC workers | 170 workers across 23 agencies which administrate LTCF in Hawaii. | A convenience sampling method was used to select participants from 23 agencies which administrate LTCF. The Maslach Burnout Inventory was used to measure burnout level. Job satisfaction was measured using the current job satisfaction scale by Kobiyama. Social support was measured using a tool by Poulin and Walter. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were used to describe the sample and to evaluate possible correlations. A multiple regression analysis was performed to study the effects of major independent variables on burnout controlling for sociodemographic variables. | This study found that a supportive work environment, social support, and a sense of belonging and support from management was key. | F | Social Support Mechanisms, Social Support Mechanisms, and Supportive Leadership and Management |

| Lower social support, lower job autonomy, lower administrative support, and a sense of isolation were barriers to job satisfaction. | B | High Coworker Conflicts and Condescending Management Style | ||||

| Kusmaul/2019 [60] | Identify factors nursing homes can adjust to improve culture for CNAs 5 and residents. | 106 CNAs employed in 3 LTCF. | A secondary analysis of data gathered from a multi-component paper survey of CNAs employed in LTC. Used results from the Nursing Home survey on Patient Safety Culture and primary shift, type of unit, and years as a CNA to identify modifiable characteristics that would explain variability in the patient safety culture perceptions. | CNAs perception of organizational culture change contributed to job satisfaction. | F | Capable Motivated Employees |

| Rao/2019 [37] | Identify the conditions in which the impact of hospital nurse staffing, nurse education, and work environment are associated with patient outcomes. | 1,262,120 general, orthopedic, and vascular surgery patients, and a random sample of 39,038 hospital staff nurses across 665 hospitals in four large states. | 30-day inpatient mortality and failure-to-rescue were the measured outcomes. | Higher professional support and support from colleagues were found to be facilitators to job satisfaction. | F | Career/Professional Development and Supportive Leadership and Management |

| Desveaux/2019 [52] | To qualitatively determine whether, how, and why an academic detailing intervention could improve evidence uptake, and to identify changes that occurred to advise outcomes for quantitative evaluation. | 11 clinical and administrative leaders, 10 physicians, 6 direct care providers, and 2 pharmacists across 13 nursing homes. | A qualitative evaluation of 29 interviews with nursing home staff, which were analyzed using the framework method. | A flexible approach, active knowledge dissemination, and in-person engagement are key components required to drive change. | F | Capable and Motivated Employees |

| Hartmann/2018 [73] | To improve resident engagement. | Six Veterans Health Administration nursing homes. | A mixed-methods study. The intervention was implemented by using evidence-based tactics for implementing quality improvement and combining CLC-based staff facilitation with researcher-led facilitation. Intervention success was assessed via structured observations and resident and staff surveys collected pre- and post-intervention. | The study found that staff job satisfaction was related to positive meaningful engagements with residents and professional development opportunities. | F | Patient-Centered Philosophy and Career/Professional Development |

| Huang/2018 [53] | To examine how the presence of owner-managers relates to the workforce outcomes of retentions and wages in Nursing Homes. | For-profit nursing homes in Ohio. | A multiple regression analysis compared workforce outcomes in facilities operated by owner-managers and salaried managers. | This study found that administrative tenure, managerial ownership, supportive environments, managerial involvement in day-to-day operations, non-profit ownership, and feeling empowered leads to greater job satisfaction. | F | Non-Profit Ownership, Capable and Motivated Employees, Non-profit Ownership, and Positive Organizational Values |

| Whitney/2018 [26] | To further the understanding of the work psychology of health support workers in LTC setting | Ontario, Canada Health service workers working in LTC | A path analysis of data collected from a survey given to the participants. | Health service workers’ (HSW) work outcomes are directly related to work attitudes, work engagement, and organizational commitment. These in turn are related to how HSWs perception of supervisory support. | F | Supportive Leadership |

| Wagner/2018 [51] | Identify the care provider’s perceptions of spirit at work. | Licensed and unlicensed care providers working in continuing care environments. | Descriptive, mixed-methods study; 18 Likert scale survey questions were further informed by two open-ended questions. | This study suggests that employees with a stronger passion and sense of trust had an increased job satisfaction. | F | Capable and Motivated Employees and Positive Organizational Values |

| Management’s inability to resolve problems was a barrier to job satisfaction. | B | Condescending Management Style | ||||

| Keisu/2018 [36] | Estimate the potential associations between employee-perceived transformational leadership style of their managers, and employees’ ratings of effort and reward within geriatric care work. | RNs, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, and assistant nurses across 9 elderly care facilities in Sweden. | Questionnaires were distributed to participants during an on-site visit. The focus was on balance at work, rather than imbalance. | This study suggests that motivating, inspirational, coaching, and intellectually stimulating managers are facilitators of job satisfaction. | F | Supportive Leadership and Management |

| Bernstein/2018 [35] | To identify ways to minimize turnover by keeping staff happy in LTC. | N/A | N/A | This study found employee enthusiasm, transparent workplaces, motivating managers, recognition from management, and sense of ownership to increase job satisfaction. | F | Capable and Motivated Employees, Supportive Leadership and Management and Career/Professional Development |

| Barriers to job satisfaction included staff feeling like they are not treated fairly, standards not being met, watching the clock, and tension among employees. | B | Condescending Management Style, Negative Perceptions about Coaching Style of Leadership and High Coworker Conflicts | ||||

| Saito/2018 [25] | Examine work engagement and burnout among nurses in long-term care hospitals in Japan and their relation to nurses’ and organizational values, and congruence of the values. | Nurses in LTC hospitals. | A cross-sectional survey of nurses in long-term care hospital and regression analyses was conducted. | This study found that selfless managers, nurses’ perception of value in their work, nurses’ perception of support, and professional development opportunities contributed to job satisfaction. | F | Supportive Leadership and Management, Enjoyment of Relationships with Patients, Social Support Mechanisms and Career/Professional Development |

| Nurses lacking knowledge and preparation, physical burdens, and managers not offering the appropriate support are contributors to burnout and lower engagement. | B | High Job Demands | ||||

| Backman/2018 [29] | To explore the relationship between the leadership of managers, job strain, and social support as perceived by direct care staff in nursing homes. | 3605 nursing home staff members. | A cross-sectional design was used. Participants completed surveys including questions concerning staff characteristics, reliable measures of nursing home managers’ leadership, job strain and social support. Statistical analyses of correlations and regression analysis were also conducted. | The positive leadership of nursing home managers was associated with a lower level of job strain and a higher level of social support among direct care staff. | F | Supportive Leadership and Management, Social Support Mechanisms and Positive Organizational Values |

| A barrier to job satisfaction was managers not taking responsibility in supporting and developing strategies to create a healthy working environment. | B | Lack of Leadership Training | ||||

| Cummings/2018 [31] | To test a model of nursing home staff perceptions of the work context, managers’ use of coaching conversations, and use of research. | 33 nursing home managers across seven Canadian nursing homes. | Participants attended a 2-day coaching development workshop. Data were collected via survey. A structural equation modeling was used to test the theoretical model of contextual characteristics of staff use of research, job satisfaction, and burnout as outcome variables and causal variables, managers’ characteristics, and coaching behaviors as mediating variables. | This study found that emotionally intelligent leadership practices, and management’s desire to support staff, were related to job satisfaction. | F | Supportive Leadership and Management and Positive Organizational Values |

| Coaching conversations and receiving feedback were found to be associated with decreased job satisfaction. | B | Negative Perceptions about Coaching Style of Leadership | ||||

| Backhaus/2018 [69] | To understand how nursing homes employ baccalaureate-educated RNs and how the contributions of the RNs to staff and residents in their organizations are viewed. | A combination of board, management, and staff in six nursing home organizations in the Netherlands | A qualitative study was conducted, consisting of 26 individual and group interviews at the board, management, and staff-level in six nursing home organizations in the Netherlands. | Organizations hired baccalaureate-educated RNs to serve as an informal leader for direct care teams. Baccalaureate-educated RN’s roles were unable to be expressed by organizations who did not employ them. Difficulties the RNs experienced during role implementation depended on role clarity, the term used to identify them, support received, transparency from direct care teams, and the RN’s own behavior. The perceived contribution of baccalaureate-educated RNs differed between organizations. | F | Adequate Job Resources |

| Bethell/2018 [44] | Examine the relationship between supervisory support and intent to turn over amid personal support workers in LTC homes and identifying whether the association is influenced by job satisfaction and the possible effect of happiness. | 5645 personal support workers in 398 LTC homes in Ontario Canada | Cross-sectional survey data from the sample was obtained and analyzed through a series of multilevel regression models. | Supervisory support on intent to turn over is mediated by job satisfaction. | F | Supportive Leadership and Management |

| Yepes-Baldó/2018 [62] | Examine the effects of job crafting activities of elder care and nursing home employees on their perceived well-being and quality of care. | 530 elderly care and nursing home employees in Spain and Sweden | Questionnaires on the Job Crafting, the General Health, and the Quality of Care were administered to participants. Correlations and hierarchical regression analyses were also performed. | A positive relationship was found between job crafting and well-being. | F | Positive Organizational Values |

| Myers/2018 [49] | To understand how LNFAs 6 thrive and keep up role performance in stressful SNF environments. | 18 LNFAs with an average of 24 years of experience. | A quantitative and qualitative analysis of interviews with participants were conducted by the research team. | This study suggests that high quality skills and safety training, exceptional health benefits, and professional development opportunities increase job satisfaction among CNAs. | F | Initial Orientation and Training, Adequate Job Resources, and Career/Professional Development |

| Barriers to job satisfaction included lack of recognition for accomplishments, heavy workloads, and lower pay. | B | Condescending Management Style, High Job Demands and Poor Compensation and Benefits | ||||

| Berridge/2018 [55] | Examine whether staff empowerment practices common to nursing home culture change are associated with CNA retention | 2034 nursing home administrators | Ordered logistic regression was used and data from 2034 nursing home administrators from a national nursing home survey was analyzed. | A high staff empowerment practice score and greater CNA empowerment opportunities were positively associated with greater retention. | F | Capable and Motivated Employees, Adequate Resources to Do the Job and Non-Profit Ownership |

| Matthews/2017 [27] | To examine the quality of manager–subordinate relationships using Leader-Member Exchange Theory (LMX) as a predictor to turnover among low-wage earners in the LTC environment. | Participants were from a large vertically integrated southeastern LTC organization. | A cross-sectional method was used to gather survey data over two periods. At time one, LMX, demographic information and job satisfaction was measured. At time two, turnover was measured. | This study suggests teamwork, support systems, versatility of foreigners, adequate work time, and working for larger organizations are associated with a higher job satisfaction. | F | Capable and Motivated Employees, Social Support Mechanisms and Adequate Job Resources |

| Poor resource management and an unclear base pay amount are barriers to job satisfaction. | B | High Job Demand sand Poor Benefits and Compensation | ||||

| Doran/2017 [30] | Examine the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and organizational factors that predicted job satisfaction for LTC employees | Long-term care employees. | A forced linear regression model was used, while controlling for age and job title, higher physical activity levels, fewer symptoms of depression, stress, and/or anxiety, less back pain, stronger social support, and reports of low work demands were assessed. | The study found that the main factor associated with job satisfaction was mood, followed by interventions to increase employees’ coping mechanisms and receiving affirmation from management. | F | Capable and Motivated Employees, Social Support Mechanisms and Supportive Leadership and Management |

| Barriers to job satisfaction included short lunch breaks and minimal access to nutritious meals. | B | Lack of Self-Care | ||||

| Pung/2017 [68] | To examine elements of job satisfaction, their demands of immigration score, explore any relationship between job satisfaction and demands of immigration, and determine the predictors of job satisfaction among international nursing staff working in LTC. | International nursing staff group, including those who are non-Singaporean, worked a minimum of one year, and nursing staff who provided direct patient care. | A cross-sectional design was used, and participants were chosen using a convenience-sampling technique. | This study found a positive workplace climate, comprehensive orientation programs, and having the proper resources to succeed were indicators of job satisfaction. | F | Initial Orientation and Training, Social Support Mechanisms, and Adequate Job Resources |

| A barrier of job satisfaction is the lack of understanding on the migration demands of nurses and job satisfaction. | B | Prohibitive Environmental Characteristics | ||||

| Harding/2017 [43] | To determine why staff in care settings are unhappy and understand the benefits of a happier staff. | Long-term care settings and employees in the United Kingdom. | Observations from field experts were included in the study. | This author/expert found that staff development opportunities, supportive managers, and recognition from management increased job satisfaction. | F | Career/Professional Development and Supportive Leadership and Management |

| A barrier to job satisfaction was the feeling of the inability to complete tasks in each time frame. | B | High Job Demands and Stress | ||||

| Boscart/2017 [74] | Changing the impact of nursing assistants’ education in seniors’ care by implementing the Living Classroom (LC) approach. | A Canadian college and nursing home group. | A collaborative approach to integrated learning was conducted where nursing assistant students, college faculty, NH teams, residents, and families engage learning together. This approach placed the student in the nursing home where knowledge, team dynamics, behaviors, relationships, and inter-professional practices are modeled. | Nursing assistant students were highly satisfied with the LC and intention to seek employment in nursing homes have increased. Nursing home teams, residents, and families exhibited positive attitudes towards educating students via LC. | F | Initial Orientation and Training |

| Chamberlain/2017 [54] | Examine organizational context, care aide characteristics, and frequency of dementia-related resident responsive behaviors associated with burnout. | 1194 care aides from 30 urban nursing homes in Canada. | A mixed-effects regression analysis was used to assess care aide characteristics, dementia-related responsive behaviors, unit and facility characteristics, and organizational context predictors of care aide burnout. Burnout was measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory form. | Unit culture and environmental resources were predictors of professional efficacy, which was associated with increased care aide job satisfaction. | F | Positive Organizational Values, Capable, and Motivated Employees and Adequate Job Resources |

| Predictors of emotional exhaustion included English as a second language, medium facility size, organizational slack-staff, organizational slack-space, personal health, and dementia-related behaviors. | B | Prohibitive Environmental Characteristics, Lack of Self-Care | ||||

| Elliott/2017 [38] | To examine an expanded demand-control-support model that included justice perceptions to determine its impact on multiple types of psychological and organizational well-being outcomes. | 173 aged care nurses. | A self-report survey was used to collect and analyze data using hierarchical multiple regression. | This study found job control, high quality training, exceptional health benefits, and professional development opportunities increase job satisfaction. | F | Adequate Job Resources, Adequate Job Resources, Initial Orientation and Training, Adequate Job Resources and Career/Professional Development |

| Barriers to job satisfaction included staffing shortages, lack of respect and recognition, low pay, and heavy workload. | B | High Job Demands, Condescending Management Style, High Job Demands and Poor Compensation and Benefits | ||||

| Adams/2017 [45] | To analyze staff perceptions of skills required and to identify discrepancies in job satisfaction, motivation, and characteristics of staff working in traditional nursing home environments and patient-centered small-scale environments. | A secondary data analysis was conducted from a previous, larger study testing the effects of small-scale living (Verbeek et al., 2009); 138 staff members were included. | A questionnaire was used to gather data on the job satisfaction, motivation, and job characteristics of nursing staff working in small-scale and traditional care environments. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze data, and multilinear regression analysis was used to test the differences between job satisfaction, motivation, and job characteristics. | In small-scale nursing homes, job satisfaction and job motivation were significantly higher compared to those in traditional nursing homes. Job autonomy and social support were also higher, while job demands were lower in small-scale nursing homes. Social support was the most notable predictor of job motivation and job satisfaction in both types of nursing home. Employee patience and motivation was a factor when determining cases where there was an intention to switch care environments. | F | Adequate Job Resources, Social Support Mechanisms, Capable and Motivated Employees and Supportive Leadership and Management |

| Tong/2017 [46] | To examine the frequency of mobbing in nursing homes and its relationships with care workers’ health status, job satisfaction, and intention to leave, and to examine the work environment as a contributing factor to mobbing. | 162 nursing homes in Switzerland with 20 or more beds, including 5311 care workers. | A cross-sectional, multi-center sub-study of the Swiss Nursing Homes Human Resource Project (SHURP). Generalized estimation equations were used to assess the relationships between mobbing and care workers’ job satisfaction, health status, desire to leave, and association of work environment factors with mobbing. | This study found that supportive leadership and open communication contributed to job satisfaction. | F | Supportive Leadership and Management |

| Employees affected by mobbing felt leadership was not supportive, felt isolated, and experienced a higher workload, which lead to job dissatisfaction. | B | High Job Demands, High Coworker Conflicts and Condescending Management Style | ||||

| Chamberlain/2016 [32] | To determine the organizational and individual variables associated with job satisfaction in care aides. | 1224 care aides from 30 LTCF homes in three Western Canadian provinces. | Participants reported job satisfaction and perception of the work environment via survey. A hierarchical, mixed-effects ordered logistic regression was used to demonstrate the odds of care aide job satisfaction for individual, care unit and facility factors. | This study found the following factors in the organizational contexts to be associated with higher care aide job satisfaction: leadership, culture, social capital, organizational slack-staff, organizational slack-space, and organizational slack-time. | F | Capable and Motivated Employees, Positive Organizational Values and Adequate Job Resources |

| The barriers to job satisfaction were emotional exhaustion and working in Alzheimer’s units. | B | Patient Complexity, Prohibitive Environmental Characteristics and Lack of Self-Care | ||||

| Schwendimann/2016 [47] | Describe job satisfaction among care workers and to examine its associations with work environment factors, work stressors, and health issues in Swiss nursing homes. | 162 Swiss nursing homes including 4145 care workers. | Care worker-reported job satisfaction was measured with a single item. Explanatory variables were assessed with established scales. Factors related to job satisfaction were examined using Generalized Estimating Equation models. | This study found work environmental factors, clear leadership, adequate resources and staffing, supportive leadership, and teamwork to contribute to job satisfaction. | F | Adequate Job Resources, Supportive Leadership and Management and Social Support Mechanisms |

| Job satisfaction decreased when workplace conflict increased, during emotional exhaustion, and when access to managing decreased. | B | High Coworker Conflicts, Lack of Self Care and Lack of Access to Management | ||||

| Wendsche/2016 [77] | To investigate how two types of care settings and types of ownership of geriatric care services influenced RNs intention to change professions. | 304 RNs working in 78 different care units in Germany. | A cross-sectional study was conducted collecting questionnaire data from RNs working in 78 care units. | This study found higher job demands, working in for-profit environments, and lack of job control to decrease job satisfaction. | B | High Job Demands, Non-Profit Ownership and Condensing Management Style |

| Roen/2016 [28] | To examine the association between patient-centered care and organizational, staff and unit characteristics in nursing homes | 175 nursing home staff in Norway | A survey was distributed including measures of patient-centered care and questions concerning staff characteristics and work-related psychosocial elements. Association with patient-centered care was analyzed using multilevel linear regression analyses. | High levels of patient-centered care, a patient-centered care work environment, and supportive leadership were associated with greater job satisfaction. | F | Patient-Centered Philosophy and Supportive Leadership and Management |

| A barrier to job satisfaction was lack of managerial leadership. | B | Lack of Leadership Training | ||||

| Gray/2016 [48] | Identify themes to potentially help CNAs make meaning out of their chosen career; thus, potentially explaining increases in job satisfaction among this group. | CNAs at three LTCFs. | Focus groups were conducted with CNAs in the three LTCFs. | This study found strong teamwork, perception of good work, making positive impacts on patients’ lives, positive relationships with residents, professional development opportunities, and recognition by leadership to result in high job satisfaction. | F | Positive Organizational Values, Patient-Centered Philosophy, Enjoyment of Relationships with Patients, Supportive Leadership and Management and Career/Professional Development |

| Lack of teamwork resulted in lower job satisfaction. | B | Lack of Peer Support | ||||

| der Zijpp/2016 [66] | To describe the interaction between managerial leaders and internal facilitators (clinical leaders acting as facilitators) and how this enabled or hindered the facilitation process of implementing urinary incontinence guideline recommendations in a local context in settings that provide LTC to elderly individuals. | 105 managers and 22 internal facilitators across four European countries. | Semi-structured interviews were conducted to collect a realist evaluation process. An interpretive data analysis unpacks interactions between managerial leaders and internal facilitators. | This study suggests that building relationships, encouragement from management, and a sense of being valued promote job satisfaction. | F | Social Support Mechanisms |

| A lack of commitment from management was a barrier to job satisfaction. | B | Condescending Management Style | ||||

| Kim/2016 [64] | Analyze the relationship between organizational structure (centralization, formalization, and span of control) and HR practices (training, horizontal communication, and vertical communication) on DCW’s job satisfaction and turnover intent. | 58 LTCFs across five states. | A latent class analysis was used to group 58 LTCF characteristics into three combination sets: “organic”: mechanistic”, and “minimalist”. The relationship of each group on direct care worker’s job satisfaction and turnover intent was tested with multivariate regression. | This study found that high levels of job training, increased communication, and higher retention lead to job satisfaction. | F | Initial Orientation and Training and Positive Organizational Values |

| A lack of training and communication can serve as a barrier to job satisfaction. | B | Lack of Training with Medically Complex Patients | ||||

| Kirkham/2016 [40] | Gain an understanding of participants’ lived experiences related to work environment quality and its link with retention; use the knowledge gained to develop a definition of work environment quality from a nursing faculty perspective; and generate grassroots recommendations that can serve as a motive for organizational change. | LPNs 7, BSNs 8, and professional nurses with a degree from a university in British Columbia. | A participatory action research method called photovoice was utilized. | This study found a stimulating physical work environment and collaborative leadership to improve job satisfaction. | F | Enjoyment of Relationships with Patients and Supportive Leadership and Management |

| A barrier to job satisfaction is an inadequate amount of time to fulfil required duties. | B | High Job Demands | ||||

| Ginsburg/2016 [56] | Validate three key work attitude measures to better understand health care aids work experiences: work engagement, psychological empowerment, and organizational citizenship behavior. | 306 health care aides working in LTC and home and community care. | Data were collected from health care aides working in LTC and home and community care using work engagement, psychological empowerment, and organizational citizenship behavior surveys. Psychometric evaluation consisted of confirmatory factor analysis. Predictive validity and internal consistency reliability were examined. | This study found work engagement, positive work attitudes, and incentive systems to predict job satisfaction. | F | Capable and Motivated Employees |

| Jenull/2015 [59] | Identify sharp patters of work stress among nurses. | 844 nurses. | Latent profile analyses were used to determine distinct patterns of work stress. Sociodemographic variables such as nurses’ living conditions and reactions to workload were considered to predict the participants’ profile membership. | Community connectedness and higher quality of life were positively associated with job satisfaction. | F | Capable and Motivated Employees |

| Working in a distressing, inpatient environment, high work demands, language barriers, understaffed, and feeling unable to provide patient centered care were barriers to job satisfaction. | B | Patient Morbidity, Language Barriers and Lack of Self Care | ||||

| Zwijsen/2015 [58] | Determine the effects of a care program for the challenging behavior of nursing home residents with dementia on burnout, job satisfaction, and job demand of care staff. | 17 Dutch dementia special care units. | Burnout, job satisfaction, and job demands were measured before the implementation, in the middle of the program, and after every unit implemented in the care program. The Dutch version of Maslach burnout inventory was used to measure burnout. Job satisfaction and demands were measured using subscales of the Leiden Quality of Work Questionnaire. Effects were determined using mixed model analyses. | Notable positive effects of using the grip on challenging behavior care programs were found on job satisfaction, without an increase placed on job demands. | F | Initial Orientation and Training and Capable and Motivated Employees |

| Thompson/2015 [80] | To consider the influence of multiple-source care funding issues on nursing-home nurses’ job satisfaction. | 13 nurses from seven nursing homes in North-East England. | Hermeneutic phenomenology was used in this study. Participants were interviewed in a sequence of five interviews, and the data were analyzed using a literary analysis method. | This study found that tension between funding and care, the feeling of “selling beds,” multiple-source care funding, and difficulty coping with self-funding residents was a barrier to nurses’ job satisfaction in the LTC setting. | B | Business Aspects Interfering with Care |

| Binney/2015 [50] | Explore the perceptions of work engagement among RNs working in LTC. | Eight RNs in an LTCF in the United States. | Eight RNs in a LTCF in the United States served as subjects in the study. | Dedicated and committed nurses increase job satisfaction. | F | Capable and Motivated Employees |

| High patient morality rates, increased workloads, and stress were barriers to job satisfaction. | B | Patient Morbidity | ||||

| Tsukamoto/2015 [61] | Investigate the associations between emotional labor, general health, and job satisfaction among long-term care workers. | 132 established, private day care centers in Tokyo | Cross-sectional study utilizing a mail survey. The outcome variables included two health-related variables and four job satisfaction variables: physical and psychological health, satisfaction with wages, interpersonal relationships, work environment, and job satisfaction. Utilized multiple regression analyses to identify significant factors. Directors from 36 facilities agreed to participate. | Findings indicated that the emotional labor of long-term care workers has a negative and positive influence on health and workplace satisfaction and suggests that care quality and stable employment among long-term care workers might affect their emotional labor. | F | Positive Organizational Values |

| Knecht/2015 [39] | Examine the attributes of LTC LPNs’ job satisfaction and dissatisfaction. | 4–12 LPNs in six LTCFs in Philadelphia. | A qualitative, 90 min focus group study was conducted at each LTCF. Four to twelve LPNs in each of the six focus groups participated in a focus group session. Herzberg’s motivation/hygiene theory (1959) provided the basis for the framework for the study. The focus group methodology allowed for the utilization of the collective power of individual and group discussion, resulting in ample data. Data analysis began after the first focus group session was complete. Utilization of member checks, expert verification, and maintenance of an audit trail contributed to trustworthiness. | This study found that work recognition and feeling valued by residents’ families increased job satisfaction | F | Supportive Leadership and Management and Relationships with Patients |

| Barriers to job satisfaction included poor pay and poor performance not being properly reprimanded by management. | B | Negative Perceptions about Coaching Style of Leadership and Poor Compensation and Benefits | ||||

| Smikle/2015 [57] | To investigate why LTC employees choose to stay and explore retention strategies for LTC. | 39 LTC employees with 10–34-year tenure rating. | Participants participated in a single, individual review. Stories relating to why employees chose to stay were gathered. | Facilitators to job satisfaction in this study included involvement in the organization, supportive and compassionate leadership, sense of connectedness, and professional development opportunities. | F | Capable and Motivated Employees, Positive Organizational Values and Career/Professional Development |

| Wallin/2015 [65] | Investigate job strain and stress of conscience among nurse assistants working in residential care and explore associations with personal and work-related aspects and health complaints. | 225 nursing assistants. | Questionnaires to measure job strain, stress of conscience, personal and work-related aspects of health complaints were completed by 225 nursing assistants. Multiple linear regression analyses were performed to compare high and low levels of job strain and stress of conscience. | Organizational and environmental support were positively associated with job satisfaction. | F | Social Support Mechanisms |

| Lack of education, poor leadership, heavy workload, and lack of opportunities to discuss difficult situations were found to be barriers to job satisfaction. | B | Lack of Training with Medically Complex Patients and High Job Demands | ||||

| Butler/2014 [71] | Explore determinants of longer job tenure for home care aides. | 261 home care aides. | Mixed-method study. Home care aides were followed for 18 months and completed two mail surveys and one phone interview. | The study found higher wages to be a predicter of job satisfaction. | F | Adequate Job Resources |

| Lack of available hours, poor compensation, poor communication, and difficulty building relationships with employing agency contributed to a decrease in job satisfaction. | B | High Job Demands and Condescending Management Style | ||||

| Zhang/2014 [33] | Identify the relationships among LTC employees’ working conditions, mental health, and desire to leave. | 1589 employees from 18 for-profit nursing homes | This is a quantitative study. Data were collected via self-administered questionnaires from 1589 for-profit nursing homes. The number of beneficial job features was constructed via a working condition index. | This study found that healthy working environments, strong interpersonal relationships, coworker support, and supervisor support contributed to job satisfaction. | F | Positive Organizational Values and Supportive Leadership and Management |

| Poor mental health was a barrier to job satisfaction. | B | Lack of Self-Care | ||||

| Wendsche/2014 [63] | Identify direct and indirect links between geriatric care setting, rest break organization, and registered nurses’ turnover assessed for one year. | 80 nursing units within 51 geriatric care services employing 597 RNs in Germany. | Multimethod cross-sectional study was used to assess nursing unites within geriatric care. | This study found collective rest breaks and working in non-profit facilities to contribute to job satisfaction. | F | Positive Organizational Values, Non-Profit Ownership |

| Willemse/2014 [70] | Highlight the consequences of small-scale care on staff’s perceived job characteristics. | 136 Dutch dementia care nursing homes with 1327 residents and 1147 staff. | Multilevel regression analyses were used to study the relationship between two indicators of small-scale care and staff’s job characteristics. | Nurses being assigned less residents/patients had a positive effect on job satisfaction in this study. | F | Adequate Job Resources |

| McGilton/2014 [72] | Understand factors that influence nurses’ intentions to continue employment at their current job. | 41 LTC nurses in seven nursing homes in Ontario, Canada. | Focus groups were conducted at the seven nursing homes through focus groups, and the discussions within the group were transcribed verbatim. Themes for the groups were developed via directed content analysis. | This study found the development of meaningful relationships with residents and professional development opportunities to promote job satisfaction. | F | Relationships with Patients and Career/Professional Development |

| Regulations on role flexibility, underfunded systems, and lack of management support were barriers to job satisfaction. | B | High Job Demand sand Negative Perceptions about Coaching Style of Leadership | ||||

| Meyer/2014 [78] | To follow rural CNAs in the US one year after training to identify retention and turnover in the LTC setting, using CAN’s perceptions of the LTC work experience. | 123 CNAs from the United States. | A longitudinal survey design was used to track CNAs completing training for one year. | The first 6 months of employment most impacted retention; 53.7% CNAs were retained after one year; and the CNAs leaving cited pay as being the number one reason for leaving. | B | High Job Demands and Poor Comp and Benefits |

| Heavy workloads were found to be a barrier to job satisfaction | Prohibitive Environmental Characteristics | |||||

| McGilton/2014 [42] | Describe the organizational, unregulated nurse and resident outcomes associated with effective supervisory performance of regulated nurses in LTC homes. | Regulated nurses working in LTC homes. | Six databases were utilized to gather articles between 2000 and 2015. Twenty-four articles were selected, and an integrative interview was performed. | Nurse supervisor performance left employees feeling empowered, increasing job satisfaction. | F | Supportive Leadership and Management |

| Poor supervision over nurses was a barrier to job satisfaction. | B | Condescending Management Style | ||||

| Chu/2014 [41] | Describe the relationship between nursing staff turnover in LTC homes and organizational factors (i.e., leadership practices and behaviors, supervisory support, burnout, job satisfaction and work environment satisfaction). | LTCF administrators. | A stress process model was used. Surveys were distributed to LTC administrators to measure organizational factors and to regulated nurses to measure sources of stress and workplace support; 324 surveys were used in a linear regression analysis to examine factors related to high turnover rates. | This study identified greater support from management, empowering work environments, and employee assistance programs as contributors to job satisfaction. | F | Supportive Leadership and Management and Social Support Mechanisms |

| Lack of supervisory support, poor leadership, administration turnover, and poor work environments were barriers to job satisfaction. | B | Condescending Management Style by Supervisor or Senior Leaders and Lack of Access to Management | ||||

| Kuo/2014 [67] | Explore the mediating effects of job satisfaction on work stress and turnover intention among LTC nurses. | LTC nurses in Taiwan. | The study used a cross-sectional survey and a correlation design. Multistage linear regression was utilized to test the mediation model. | Low stress levels among LTC employees lead to a higher job satisfaction. | F | Social Support Mechanisms |

| Barriers to job satisfaction include high stress levels, unfair working hours, and lack of supportive leadership. | B | High Job Demands | ||||

| Jungyoon/2014 [79] | To examine the relationship between organizational structure and HR practices on job satisfaction and turnover intent. | 50 LTC facilities across five states. | A latent class analysis was used to group facility characteristics into three sets of combinations. A multivariate regression was used to test the relationship between groups on job satisfaction and turnover intent. | This study found low levels of job training and communication to be barriers to job satisfaction. | B | Lack of Training with Medically Complex Patients |

References

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Ageing 2019 Highlights; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mather, M.; Jacobsen, L.A.; Pollard, K.M. Aging in the United States. Popul. Bull. 2015, 70, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mather, M.; Scommegna, P.; Kilduff, L. Fact Sheet: Aging in the United States. Available online: https://www.prb.org/aging-unitedstates-fact-sheet/# (accessed on 22 September 2020).

- McPhillips, D. Aging in America, in 5 Charts. U.S. News World Reports, 30 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health. Long-Term Care Providers and Services Users in the United States, 2015–2016; National Center for Health: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2019.

- Abraham, S. Job Satisfaction as an Antecedent to Employee Engagement. SIES J. Manag. 2012, 8, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kaldenberg, D.; Regrut, B. Do satisfied patients depend on satisfied employees? Or, do satisfied employees depend on satisfied patients? QRC Advis. 1999, 15, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ganey, P. Achieving Excellence: The Convergence of Safety, Quality, Experience and Caregiver Engagement; Press Ganey: South Bend, IN, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ganey, P. A Strategic Blueprint for Transformational Change; Press Ganey: South Bend, IN, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ganey, P. Accelerating Transformation: Translating Strategy into Action; Press Ganey: South Bend, IN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Syptak, M.; Marsland, D.; Ulmer, D. Job satisfaction: Putting theory into practice. Fam. Pract. Manag. 1999, 6, 26. [Google Scholar]

- O’hara, M.A.; Burke, D.; Ditomassi, M.; Lopez, R.P. Assessment of Millennial Nurses’ Job Satisfaction and Professional Practice Environment. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2019, 49, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middaugh, D.J. Don’t feed the bears! Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 45, 101–102. [Google Scholar]

- Dans, M.; Lundmark, V. The effects of positive practice environments. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 50, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, E. What Is the Price of Disengaged Healthcare Workers? Available online: https://electronichealthreporter.com/what-is-the-price-of-disengaged-healthcare-workers/ (accessed on 22 September 2020).

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Civil Money Penalty Reinvestment Program; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Baltiomore, MD, USA, 2018.

- Dewey, C.; Hingle, S.; Goelz, E.; Linzer, M. Supporting Clinicians during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 172, 752–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, S.X.; Liu, J.; Jahanshahi, A.A.; Nawaser, K.; Yousefi, A.; Li, J.; Sun, S. At the height of the storm: Healthcare staff’s health conditions and job satisfaction and their associated predictors during the epidemic peak of COVID-19. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 144–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar]

- Mileski, M.; Henriksen, A.; Farzi, J.; Adeleke, I.; Chan, R.; Kruse, C. Writing a Systematic Review for Publication in a Health-Related Degree Program. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2019, 8, e15490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera, A.J.; Garrett, J.M. Understanding interobserver agreement: The kappa statistic. Fam. Med. 2005, 37, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aloisio, L.D.; Baumbusch, J.; Estabrooks, C.A.; Boström, A.-M.; Chamberlain, S.; Cummings, G.G.; Thompson, G.; Squires, J.E. Factors affecting job satisfaction in long-term care unit managers, directors of care and facility administrators: A secondary analysis. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 1764–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malagón-Aguilera, M.C.; Suñer-Soler, R.; Bonmatí-Tomas, A.; Bosch-Farré, C.; Gelabert-Vilella, S.; Juvinyà-Canal, D. Relationship between sense of coherence, health and work engagement among nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escrig-Pinol, A.; Hempinstall, M.; McGilton, K.S. Unpacking the multiple dimensions and levels of responsibility of the charge nurse role in long-term care facilities. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2019, 14, e12259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Igarashi, A.; Noguchi-Watanabe, M.; Takai, Y.; Yamamoto-Mitani, N. Work values and their association with burnout/work engagement among nurses in long-term care hospitals. J. Nurs. Manag. 2018, 26, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berta, W.; Laporte, A.; Perreira, T.; Ginsburg, L.; Dass, A.R.; Deber, R.B.; Baumann, A.; Cranley, L.A.; Bourgeault, I.L.; Lum, J.; et al. Relationships between work outcomes, work attitudes and work environments of health support workers in Ontario long-term care and home and community care settings. Hum. Resour. Health 2018, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, M.; Carsten, M.K.; Ayers, D.J.; Menachemi, N. Determinants of turnover among low wage earners in long term care: The role of manager-employee relationships. Geriatr. Nurs. 2018, 39, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røen, I.; Kirkevold, O.; Testad, I.; Selbæk, G.; Engedal, K.; Bergh, S. Person-centered care in Norwegian nursing homes and its relation to organizational factors and staff characteristics: A cross-sectional survey. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2017, 30, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Backman, A.; Sjögren, K.; Lövheim, H.; Edvardsson, D. Job strain in nursing homes-Exploring the impact of leadership. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 1552–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, K.; Resnick, B.; Swanberg, J. Factors Influencing Job Satisfaction among Long-Term Care Staff. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 59, 1109–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, G.G.; Hewko, S.J.; Wang, M.; A Wong, C.; Laschinger, H.K.S.; Estabrooks, C.A. Impact of Managers’ Coaching Conversations on Staff Knowledge Use and Performance in Long-Term Care Settings. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2017, 15, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberlain, S.A.; Hoben, M.; Squires, J.E.; Estabrooks, C.A. Individual and organizational predictors of health care aide job satisfaction in long term care. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Punnett, L.; Gore, R. The CPH-NEW Research Team Relationships among Employees’ Working Conditions, Mental Health, and Intention to Leave in Nursing Homes. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2012, 33, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Liu, L.; Ishikawa, H.; Park, S.-H. Relationships between social support, job autonomy, job satisfaction, and burnout among care workers in long-term care facilities in Hawaii. Educ. Gerontol. 2019, 45, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, A. Minimise turnover by keeping staff happy. Nurs. Resid. Care 2018, 20, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keisu, B.-I.; Öhman, A.; Enberg, B. Employee effort—reward balance and first-level manager transformational leadership within elderly care. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2017, 32, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.D.; Evans, L.K.; Mueller, C.A.; Lake, E.T. Professional networks and support for nursing home directors of nursing. Res. Nurs. Health 2019, 42, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, K.-E.J.; Rodwell, J.; Martín, A.J. Aged care nurses’ job control influence satisfaction and mental health. J. Nurs. Manag. 2017, 25, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knecht, P. Demystifying Job Satisfaction in Long-Term Care: The Voices of Licensed Practical Nurses. Ph.D. Thesis, The Pensylvania State University, State College, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham, A. Enhancing Nurse Faculty Retention through Quality Work Environments: A Photovoice Project. Nurs. Econ. 2016, 34, 289–295. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, C.H.; Wodchis, W.P.; McGilton, K.S. Turnover of regulated nurses in long-term care facilities. J. Nurs. Manag. 2013, 22, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGilton, K.S.; Chu, C.H.; Shaw, A.C.; Wong, R.; Ploeg, J. Outcomes related to effective nurse supervision in long-term care homes: An integrative review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 1007–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, C. Job satisfaction as an alternative approach to staff development. J. Dementia Care 2017, 25, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Bethell, J.; Chu, C.H.; Wodchis, W.P.; Walker, K.; Stewart, S.C.; McGilton, K.S. Supportive Supervision and Staff Intent to Turn Over in Long-Term Care Homes. Gerontology 2017, 58, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.; Verbeek, H.; Zwakhalen, S.M.G. The Impact of Organizational Innovations in Nursing Homes on Staff Perceptions: A Secondary Data Analysis. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2017, 49, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.; Schwendimann, R.; Zúñiga, F. Mobbing among care workers in nursing homes: A cross-sectional secondary analysis of the Swiss Nursing Homes Human Resources Project. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 66, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwendimann, R.; Dhaini, S.; Ausserhofer, D.; Engberg, S.; Zúñiga, F. Factors associated with high job satisfaction among care workers in Swiss nursing homes—A cross sectional survey study. BMC Nurs. 2016, 15, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gray, M.; Shadden, B.; Henry, J.; Di Brezzo, R.; Ferguson, A.; Fort, I. Meaning making in long-term care: What do certified nursing assistants think? Nurs. Inq. 2016, 23, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, D.; Rogers, R.; Lecrone, H.H.; Kelley, K.; Scott, J.H. Work Life Stress and Career Resilience of Licensed Nursing Facility Administrators. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2016, 37, 435–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binney, I. Registered Nurses’ Perceptions of Work Engagement and Turnover Intentions in a Long-Term Care Facility: A Case Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Northcentral University, Scottsdale, AR, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, J.I.; Brooks, D.; Urban, A.-M. Health Care Providers’ Spirit at Work Within a Restructured Workplace. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2016, 40, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desveaux, L.; Halko, R.; Marani, H.; Feldman, S.; Ivers, N.M. Importance of Team Functioning as a Target of Quality Improvement Initiatives in Nursing Homes. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2019, 39, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.S.; Bowblis, J.R. Workforce Retention and Wages in Nursing Homes: An Analysis of Managerial Ownership. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2018, 902–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberlain, S.A.; Gruneir, A.; Hoben, M.; Squires, J.E.; Cummings, G.G.; Estabrooks, C.A. Influence of organizational context on nursing home staff burnout: A cross-sectional survey of care aides in Western Canada. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2017, 71, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berridge, C.; Tyler, D.A.; Miller, S.C. Staff Empowerment Practices and CNA Retention: Findings from a Nationally Representative Nursing Home Culture Change Survey. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2016, 37, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ginsburg, L.; Berta, W.; Baumbusch, J.; Dass, A.R.; Laporte, A.; Reid, R.C.; Squires, J.; Taylor, D. Measuring Work Engagement, Psychological Empowerment, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior Among Health Care Aides. Gerontology 2016, 56, e1–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smikle, J.L. Why They Stay: Retention Strategies for Long Term Care. The Reasons That Staff Stay on Have Everything to Do with the Company’s Commitment to Them as Individuals. Provider 2015, 41, 39, 40, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Zwijsen, S.; Gerritsen, D.; Eefsting, J.; Smalbrugge, M.; Hertogh, C.; Pot, A.M. Coming to grips with challenging behaviour: A cluster randomised controlled trial on the effects of a new care programme for challenging behaviour on burnout, job satisfaction and job demands of care staff on dementia special care units. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jenull, B.; Wiedermann, W. The Different Facets of Work Stress. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2013, 34, 823–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmaul, N.; Sahoo, S. Hypothesis Testing of CNA Perceptions of Organizational Culture in Long Term Care. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2019, 62, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, E.; Abe, T.; Ono, M. Inverse roles of emotional labour on health and job satisfaction among long-term care workers in Japan. Psychol. Health Med. 2014, 20, 814–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepes-Baldó, M.; Romeo, M.; Westerberg, K.; Nordin, M. Job Crafting, Employee Well-being, and Quality of Care. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2016, 40, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wendsche, J.; Hacker, W.; Wegge, J.; Schrod, N.; Roitzsch, K.; Tomaschek, A.; Kliegel, M. Rest break organization in geriatric care and turnover: A multimethod cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 1246–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Cho, E.J. Quercetin and quercetin-3-β-d-glucoside improve cognitive and memory function in Alzheimer’s disease mouse. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2016, 59, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, A.O.; Jakobsson, U.; Edberg, A.-K. Job strain and stress of conscience among nurse assistants working in residential care. J. Nurs. Manag. 2013, 23, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Zijpp, T.J.; Niessen, T.; Eldh, A.C.; A Hawkes, C.; McMullan, C.; Mockford, C.; Wallin, L.; McCormack, B.; Rycroft-Malone, J.; Seers, K.; et al. A Bridge over Turbulent Waters: Illustrating the Interaction between Managerial Leaders and Facilitators When Implementing Research Evidence. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2016, 13, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, H.-T.; Lin, K.-C.; Li, I.-C. The mediating effects of job satisfaction on turnover intention for long-term care nurses in Taiwan. J. Nurs. Manag. 2013, 22, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pung, L.-X.; Shorey, S.; Goh, Y.S. Job satisfaction, demands of immigration among international nursing staff working in the long-term care setting: A cross-sectional study. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2017, 36, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, R.; Verbeek, H.; Van Rossum, E.; Capezuti, E.A.; Hamers, J.P. Baccalaureate-educated Registered Nurses in nursing homes: Experiences and opinions of administrators and nursing staff. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 74, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemse, B.; Depla, M.; Smit, D.; Pot, A.M. The relationship between small-scale nursing home care for people with dementia and staff’s perceived job characteristics. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, S.S.; Brennan-Ing, M.; Wardamasky, S.; Ashley, A. Determinants of Longer Job Tenure Among Home Care Aides: What Makes Some Stay on the Job While Others Leave? J. Appl. Gerontol. 2014, 33, 164–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGilton, K.S.; Boscart, V.M.; Brown, M.; Bowers, B.J. Making tradeoffs between the reasons to leave and reasons to stay employed in long-term care homes: Perspectives of licensed nursing staff. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, C.W.; Mills, W.L.; Pimentel, C.B.; A Palmer, J.; Allen, R.S.; Zhao, S.; Wewiorski, N.J.; Sullivan, J.L.; Dillon, K.; Clark, V.; et al. Impact of Intervention to Improve Nursing Home Resident–Staff Interactions and Engagement. Gerontology 2018, 58, e291–e301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boscart, V.M.; D’Avernas, J.; Brown, P.; Raasok, M. Changing the Impact of Nursing Assistants’ Education in Seniors’ Care: The Living Classroom in Long-Term Care. Can. Geriatr. J. 2017, 20, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rajamohan, S.; Porock, D.; Chang, Y.-P. Understanding the Relationship between Staff and Job Satisfaction, Stress, Turnover, and Staff Outcomes in the Person-Centered Care Nursing Home Arena. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2019, 51, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perreira, T.A.; Berta, W.; Laporte, A.; Ginsburg, L.; Deber, R.B.; Elliott, G.; Lum, J. Shining a Light: Examining Similarities and Differences in the Work Psychology of Health Support Workers Employed in Long-Term Care and Home and Community Care Settings. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2017, 38, 1595–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendsche, J.; Hacker, W.; Wegge, J.; Rudolf, M. High job demands and low job control increase nurses’ professional leaving intentions: The role of care setting and profit orientation. Res. Nurs. Health 2016, 39, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D.; Raffle, H.; Ware, L.J. The first year: Employment patterns and job perceptions of nursing assistants in a rural setting. J. Nurs. Manag. 2012, 22, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Wehbi, N.K.; DelliFraine, J.L.; Brannon, D. The joint relationship between organizational design factors and HR practice factors on direct care workers’ job satisfaction and turnover intent. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2014, 39, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.; Cook, G.; Duschinsky, R. ‘I feel like a salesperson’: The effect of multiple-source care funding on the experiences and views of nursing home nurses in England. Nurs. Inq. 2014, 22, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirkovská, B.; Janečková, H. Workplace stress and employees’ well-being: Evidence from long-term care in the Czech Republic. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 27, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bortolotti, T.; Boscari, S.; Danese, P.; Suni, H.A.M.; Rich, N.; Romano, P. The social benefits of kaizen initiatives in healthcare: An empirical study. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 554–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Facilitators | Occurrences by Article Reference Number | Total Occurrences (n = 162) | Percent of Occurrences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supportive Leadership | [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48] | 51 | 31.48% |

| Capable and Motivated Employees | [22,26,30,32,35,45,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60] | 25 | 15.43% |

| Positive Organizational Values | [22,23,24,29,31,32,33,48,51,53,54,57,60,61,62,63,64] | 20 | 12.35% |

| Social Support Mechanisms | [22,23,25,29,30,34,41,45,47,65,66,67,68] | 15 | 9.26% |

| Adequate Job Resources | [32,38,45,47,54,55,69,70,71] | 11 | 6.79% |

| Career/Professional Development | [25,35,37,38,43,48,57,72,73] | 10 | 6.17% |

| Initial Orientation and Training | [22,38,58,64,68,74] | 9 | 5.56% |

| Patient-Centered Philosophy | [22,28,48,73,75] | 9 | 5.56% |

| Enjoyment of Relationships with Patients | [25,39,40,48,72,76] | 7 | 4.32% |

| Non-Profit Ownership | [53,55,63] | 4 | 2.47% |

| Organizational Systems and Processes | [22] | 1 | 0.62% |

| Barriers | Occurrences by Article Reference Number | Total Occurrences (n = 98) | Percent of Occurrences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Condescending Management Style | [27,34,35,38,41,42,46,51,66,71,77] | 15 | 15.31% |

| High Job Demands | [25,38,40,43,46,65,67,71,72,77,78] | 13 | 13.27% |

| Lack of Self-Care | [30,32,33,46,47,54,59] | 9 | 9.18% |

| Lack of Training with Medically Complex Patients | [22,24,25,65,75,79] | 8 | 8.16% |

| Prohibitive Environmental Characteristics | [22,32,54,68,78] | 8 | 8.16% |

| Lack of Leadership Training | [22,24,27,28,29,31] | 7 | 7.14% |

| Business Aspects Interfering with Care | [24,80,81] | 7 | 7.14% |

| High Coworker Conflicts | [34,35,46,47,76] | 6 | 6.12% |

| Negative Perceptions about Coaching Style of Leadership | [31,35,39,72] | 5 | 5.10% |

| Stress | [27,30,43,67] | 5 | 5.10% |

| Lack of Access to Management | [22,35,41,47] | 4 | 4.08% |

| Poor Compensation and Benefits | [38,39,78] | 3 | 3.06% |

| Lack of Peer Support | [22,48] | 2 | 2.04% |

| Patient Morbidity | [50,59] | 2 | 2.04% |

| Limited Communication Opportunities | [22] | 1 | 1.02% |

| Language Barriers | [59] | 1 | 1.02% |

| Non-Profit Ownership | [77] | 1 | 1.02% |

| Patient Complexity | [32] | 1 | 1.02% |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, K.; Mileski, M.; Fohn, J.; Frye, L.; Brooks, L. Facilitators and Barriers Surrounding the Role of Administration in Employee Job Satisfaction in Long-Term Care Facilities: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2020, 8, 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040360

Lee K, Mileski M, Fohn J, Frye L, Brooks L. Facilitators and Barriers Surrounding the Role of Administration in Employee Job Satisfaction in Long-Term Care Facilities: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2020; 8(4):360. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040360

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Kimberly, Michael Mileski, Joanna Fohn, Leah Frye, and Lisa Brooks. 2020. "Facilitators and Barriers Surrounding the Role of Administration in Employee Job Satisfaction in Long-Term Care Facilities: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 8, no. 4: 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040360

APA StyleLee, K., Mileski, M., Fohn, J., Frye, L., & Brooks, L. (2020). Facilitators and Barriers Surrounding the Role of Administration in Employee Job Satisfaction in Long-Term Care Facilities: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 8(4), 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040360