Quality and Safety in Healthcare for Medical Students: Challenges and the Road Ahead

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Course Content

2.2. Participants and Procedures

2.3. Ethical Approval

2.4. Instruments

2.4.1. To Evaluate Perceptions and Attitudes of Students

2.4.2. To Evaluate Students’ Knowledge Concerning the Course and to Get Insights into the Regional Environment Perception of Students

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Suggestions for Further Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, J.; Salisbury, H. Attitudes and Perceptions of NonClinical Health Care Students Towards Interprofessional Learning. Health Interprof. Pract. Educ. 2019, 3, eP1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiott, D.B.; Phillips, S.; Amella, E. Adolescent Risk Screening Instruments for Primary Care: An Integrative Review Utilizing the Donabedian Framework. Compr. Child Adolesc. Nurs. 2018, 41, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tully, V.; Murphy, D.; Fioratou, E.; Chaudhuri, A.; Shaw, J.; Davey, P. Learning from errors: Assessing final year medical students’ reflection on safety improvement, five year cohort study. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, G.; Cracknell, A.; Forrest, K.; Sandars, J. Twelve tips for implementing a patient safety curriculum in an undergraduate programme in medicine. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Feijter, J.M.; de Grave, W.S.; Hopmans, E.M.; Koopmans, R.P.; Scherpbier, A.J. Reflective learning in a patient safety course for final-year medical students. Med. Teach. 2012, 34, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, H.; Park, S.J.; Kim, T. Patient safety education to change medical students’ attitudes and sense of responsibility. Med. Teach. 2015, 37, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, M.; Woodward, H.; Van Staalduinen, S.; Lemer, C.; Greaves, F.; Noble, D.; Ellis, B.; Donaldson, L.; Barraclough, B.; Expert Group convened by the World Alliance of Patient Safety. The WHO patient safety curriculum guide for medical schools. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2010, 19, 542–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Madigosky, W.S.; Headrick, L.A.; Nelson, K.; Cox, K.R.; Anderson, T. Changing and sustaining medical students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes about patient safety and medical fallibility. Acad. Med. 2006, 81, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabilou, B.; Feizi, A.; Seyedin, H. Patient Safety in Medical Education: Students’ Perceptions, Knowledge and Attitudes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, K.P.; Goyal, S.; Ramachandran, V.; Kohn, J.R.; Go, J.A.; Wiley, Z.; Moturu, A.; Namireddy, M.K.; Kumar, A.; Jacobs, R.C.; et al. Efficacy of quality improvement and patient safety workshops for students: A pilot study. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Byrne, L. Medical students and COVID-19: The need for pandemic preparedness. J. Med. Ethics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mexico, G.D. Seguridad del Paciente: Prioridad del Sector Salud. Secretaría de Salud, Gobierno de México. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/salud/articulos/conoce-las-acciones-esenciales-para-la-seguridad-del-paciente?idiom=es (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Stokes, D.C. Senior Medical Students in the COVID-19 Response: An Opportunity to Be Proactive. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020, 27, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barajas-Ochoa, A.; Andrade-Romo, J.S.; Ramos-Santillan, V.O. Challenges for medical education in Mexico in the time of COVID-19. Gac Med. Mex 2020, 156, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, S. Medical Student Education in the Time of COVID-19. JAMA 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon-Cortes, J.L.; Leal Fernandez, G.; Sanchez-Perez, H.J. Health reform in Mexico: Governance and potential outcomes. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez-Bolaños, R.; Cartujano-Barrera, F.; Cartujano, B.; Flores, Y.N.; Cupertino, A.P.; Gallegos-Carrillo, K. The Urgent Need to Address Violence Against Health Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Med. Care 2020, 58, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuters. Mexico Has World’s Most Health Worker Deaths from Pandemic, Amnesty International Says. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-mexico-amnesty-idUSKBN25U35G (accessed on 23 November 2020).

- Ortega, J.; Cometto, M.C.; Zarate Grajales, R.A.; Malvarez, S.; Cassiani, S.; Falconi, C.; Friedeberg, D.; Peragallo-Montano, N. Distance learning and patient safety: Report and evaluation of an online patient safety course. Rev. Panam Salud Publica 2020, 44, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamui-Sutton, A.; Pérez-Castro, A.; Vázquez Verónica Durán-Pérez, D.; García-Téllez, S.E.; Fernández-Cantón, S.B.; Lezana-Fernández, M.A.; Carrasco-Roja, J.A. Patient’s safety culture perception by resident physicians in Mexico. Revista CONAMED 2015, 20, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19: Mexico Must Prevent the Collapse of Its Health System. Available online: https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/english/covid-19-mexico-must-prevent-collapse-its-health-system (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Martinez-Martinez, O.A.; Rodriguez-Brito, A. Vulnerability in health and social capital: A qualitative analysis by levels of marginalization in Mexico. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Question | Most Plausible Answer (Percentage) | Other Answers (Percentage) |

|---|---|---|

| According to the dimensions of the quality of the IOM, which would be awarded the first place in importance at this moment (pandemic) to avoid the collapse of the health system? | Efficiency (39.1%) | Safety (0.45%), effectiveness (32.2), timeliness, (6.1%), patient-centered (21.7%), and equitable (0.45%). |

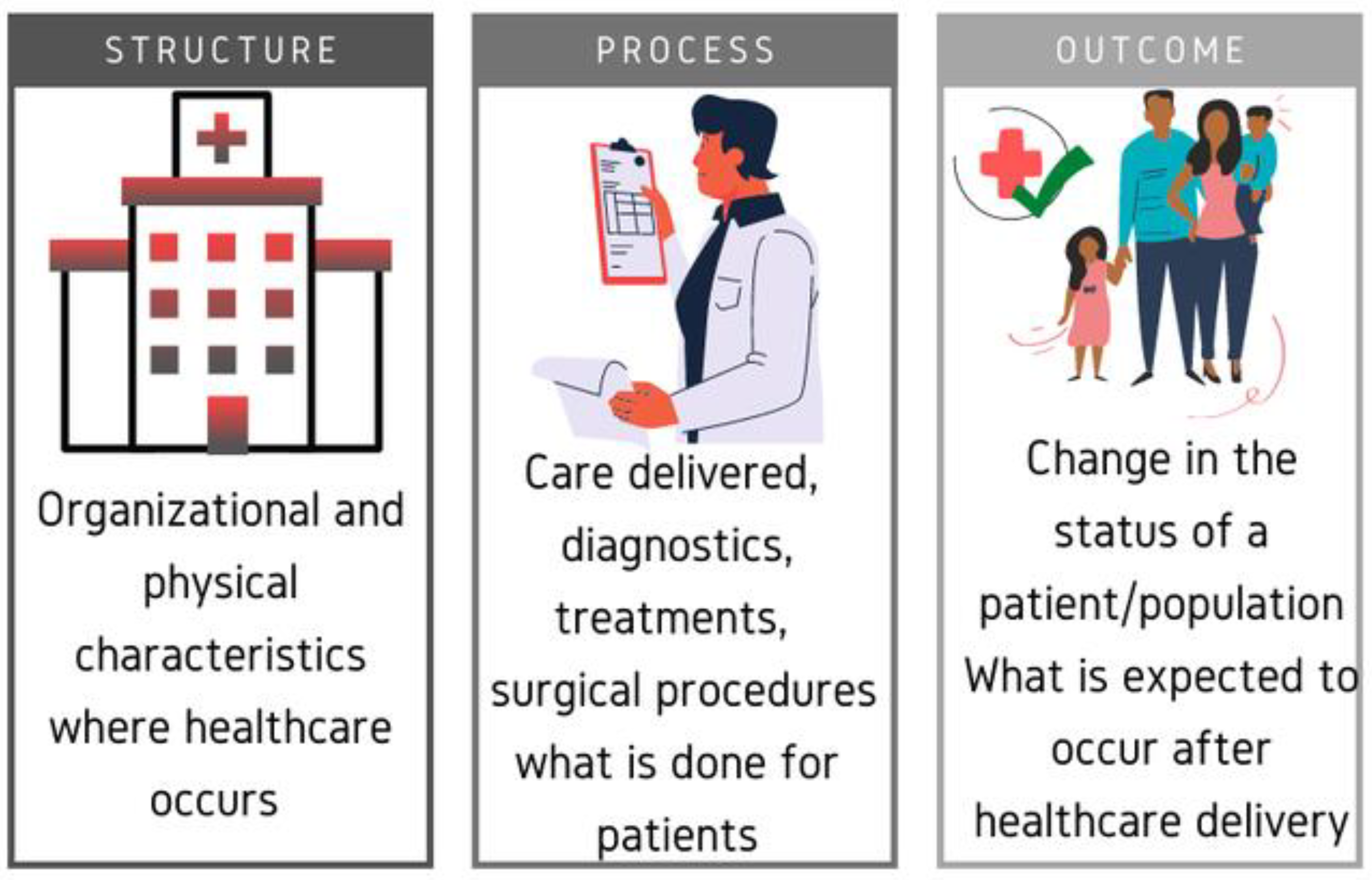

| According to the Avedis Donabedian model of quality, the lack of mechanical ventilators to fulfill the needs of the current pandemic corresponds to… | Infrastructure-equipment (95.5%) | Process-environment (2.6%) Process-management (0.9%) |

| In which of the elements of the Avedis Donabedian quality model do you think Mexico is worst? | Structure (53.9%) | Process 27.8% Results 18.3% |

| In which of the elements of the Avedis Donabedian quality model do you think Mexico is best? | Process (47%) | Structure (26%) Results (27%) |

| If a patient enters the emergency room for acute abdominal pain and derived from the current health contingency, acquires COVID-19 infection in the hospital and dies of respiratory complications, what type of event would be? | Sentinel (72.2%) | Adverse event (25.2%) Near miss (2.6%) |

| Teaching Items of Patient Safety Education and Skills | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sentence | Students | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | p-Value |

| Physicians should routinely spend part of their professional time working to improve patient care | Female | 29 | 1 | 3 | 40 | 0 | 0.84 |

| Male | 19 | 0 | 2 | 20 | 0 | ||

| Patient safety’ is an important topic | Female | 8 | 65 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.38 |

| Male | 6 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Physicians should routinely report medical errors | Female | 31 | 1 | 2 | 39 | 0 | 0.11 |

| Male | 14 | 2 | 1 | 24 | 0 | ||

| Learning how to improve patient safety is an appropriate use of time in medical school | Female | 32 | 3 | 3 | 34 | 1 | 0.60 |

| Male | 25 | 1 | 3 | 12 | 0 | ||

| Would like to receive further teaching on patient safety | Female | 34 | 32 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0.22 |

| Male | 12 | 25 | 3 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Supporting and advising a peer who must decide how to respond to an error | Female | 37 | 6 | 20 | 9 | 1 | 0.45 |

| Male | 22 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 0 | ||

| Analyzing a case to find the cause of an error | Female | 37 | 6 | 20 | 10 | 0 | 0.46 |

| Male | 20 | 1 | 11 | 9 | 0 | ||

| Disclosing an error to a faculty member | Female | 36 | 1 | 3 | 33 | 0 | 0.84 |

| Male | 23 | 0 | 2 | 16 | 0 | ||

| Causes of Errors | |||||||

| Sentence | Group | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | p-Value |

| Making errors in medicine is inevitable. | Female | 31 | 35 | 26 | 34 | 5 | 0.04 |

| Male | 28 | 24 | 9 | 13 | 8 | ||

| There is a gap between what is known as “best care” and what is being provided on a day-to-day basis | Female | 37 | 65 | 12 | 16 | 1 | 0.49 |

| Male | 26 | 40 | 9 | 5 | 2 | ||

| Competent health practitioners do not make medical errors that lead to patient harm | Female | 6 | 22 | 26 | 68 | 9 | 0.43 |

| Male | 6 | 14 | 15 | 36 | 11 | ||

| Most errors are due to things that health practitioners cannot do anything about | Female | 1 | 7 | 30 | 73 | 20 | 0.37 |

| Male | 2 | 8 | 23 | 37 | 12 | ||

| Error Management | |||||||

| Sentence | Students | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | p-Value |

| Only physicians can determine the causes of a medical error | Female | 9 | 23 | 28 | 57 | 14 | 0.57 |

| Male | 8 | 18 | 13 | 31 | 12 | ||

| If there is no harm to a patient, there is no need to address an error | Female | 2 | 13 | 14 | 61 | 41 | 0.72 |

| Male | 2 | 7 | 5 | 44 | 24 | ||

| Reporting systems do little to reduce future errors | Female | 12 | 24 | 28 | 51 | 16 | 0.10 |

| Male | 2 | 22 | 12 | 31 | 15 | ||

| After an error occurs, an effective strategy is to work harder and to be more careful | Female | 80 | 46 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0.22 |

| Male | 45 | 30 | 1 | 5 | 1 | ||

| health practitioners should not tolerate uncertainty in patient care | Female | 9 | 51 | 30 | 35 | 6 | 0.21 |

| Male | 12 | 25 | 14 | 25 | 6 | ||

| The culture of medicine makes it easy for providers to deal constructively with errors | Female | 22 | 67 | 19 | 19 | 4 | 0.51 |

| Male | 20 | 34 | 10 | 15 | 3 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Hernández, L.B.; Díaz, B.G.; Zamora González, E.O.; Montes-Hernández, K.I.; Tlali Díaz, S.S.; Toledo-Lozano, C.G.; Bustamante-Montes, L.P.; Vázquez Cárdenas, N.A. Quality and Safety in Healthcare for Medical Students: Challenges and the Road Ahead. Healthcare 2020, 8, 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040540

López-Hernández LB, Díaz BG, Zamora González EO, Montes-Hernández KI, Tlali Díaz SS, Toledo-Lozano CG, Bustamante-Montes LP, Vázquez Cárdenas NA. Quality and Safety in Healthcare for Medical Students: Challenges and the Road Ahead. Healthcare. 2020; 8(4):540. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040540

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Hernández, Luz Berenice, Benjamín Gómez Díaz, Edgar Oswaldo Zamora González, Karen Itzel Montes-Hernández, Stephanie Simone Tlali Díaz, Christian Gabriel Toledo-Lozano, Lilia Patricia Bustamante-Montes, and Norma Alejandra Vázquez Cárdenas. 2020. "Quality and Safety in Healthcare for Medical Students: Challenges and the Road Ahead" Healthcare 8, no. 4: 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040540

APA StyleLópez-Hernández, L. B., Díaz, B. G., Zamora González, E. O., Montes-Hernández, K. I., Tlali Díaz, S. S., Toledo-Lozano, C. G., Bustamante-Montes, L. P., & Vázquez Cárdenas, N. A. (2020). Quality and Safety in Healthcare for Medical Students: Challenges and the Road Ahead. Healthcare, 8(4), 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040540