Multistakeholder Participation in Disaster Management—The Case of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Synthesis of Literature Review

2.1. Multi-Stakeholder Participation

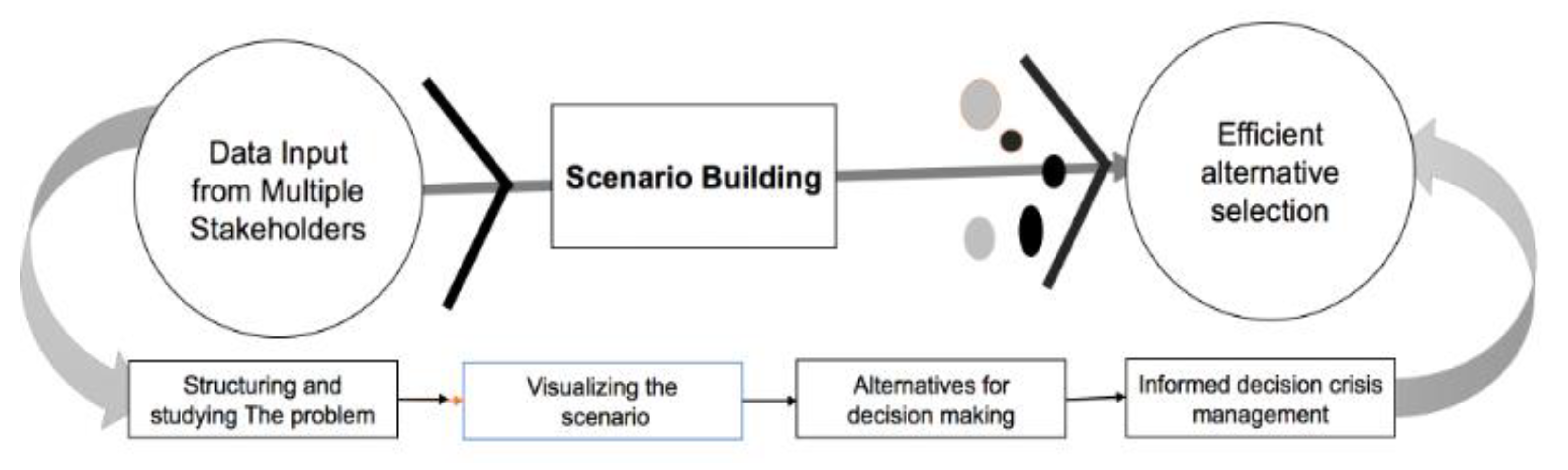

2.2. Interlinking of Multi-Stakeholder Spatial Decision Support System (MS-SDSS)

3. Methodology

Review of Global Methodological Procedures

4. Scientific Review Results

4.1. Taxonomy of COVID-19

4.2. Emerging Trends in Multi-Stakeholder Participation

4.3. Enhancing Nationwide Preparedness and Responses

5. Policy Announcement from Selected Countries for COVID-19

Strategies Followed to Combat COVID-19

6. Discussion

Importance and Implications of Public Policies

7. Suggestions for Effective Interventions

Scope for Future Research

8. Limitations

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. If the world fails to protect the economy, COVID-19 will damage health not just now but also in the future. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 640–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Anyfantaki, S.; Balfoussia, H.; Dimitropoulou, D.; Gibson, H.; Papageorgiou, D.; Petroulakis, F.; Theofilakou, A.; Vasardani, M. COVID-19 and other pandemics: A literature review for economists. Econ. Bull. 2020, 51, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jordà, Ò.; Singh, S.R.; Taylor, A.M. Longer-Run Economic Consequences of Pandemics; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eweje, G.; Sajjad, A.; Nath, S.D.; Kobayashi, K. Multi-stakeholder partnerships: A catalyst to achieve sustainable development goals. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P. Studying COVID-19 in Light of Critical Approaches to Risk and Uncertainty: Research Pathways, Conceptual Tools, and Some Magic from Mary Douglas; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ramkissoon, H. COVID-19 place confinement, pro-social, pro-environmental behaviors, and residents’ wellbeing: A new conceptual framework. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franch-Pardo, I.; Napoletano, B.M.; Rosete-Verges, F.; Billa, L. Spatial analysis and GIS in the study of COVID-19. A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 140033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, L. After Covid-19: Urban design as spatial medicine. Urban Des. Int. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Su, F.; Pei, T.; Zhang, A.; Du, Y.; Luo, B.; Cao, Z.; Wang, J.; Yuan, W.; Zhu, Y.; et al. COVID-19: Challenges to GIS with Big Data. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourghasemi, H.R.; Pouyan, S.; Heidari, B.; Farajzadeh, Z.; Fallah Shamsi, S.R.; Babaei, S.; Khosravi, R.; Etemadi, M.; Ghanbarian, G.; Farhadi, A.; et al. Spatial modeling, risk mapping, change detection, and outbreak trend analysis of coronavirus (COVID-19) in Iran (days between 19 February and 14 June 2020). Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 98, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biekart, K.; Fowler, A. Ownership dynamics in local multi-stakeholder initiatives. Third World Q. 2018, 39, 1692–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kain, J.-H. Multistakeholder Participation. In Encyclopedia of Geography; Warf, B., Ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 1957–1959. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, A.; Clarke, A.; Huang, L. Multi-stakeholder partnerships for sustainability: Designing decision-making processes for partnership capacity. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 160, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkle, F.M.; Bradt, D.A.; Ryan, B.J. Global public health database support to population-based management of pandemics and global public health crises, part I: The concept. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2020, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorram-Manesh, A.; Carlström, E.; Hertelendy, A.J.; Goniewicz, K.; Casady, C.B.; Burkle, F.M. Does the prosperity of a country play a role in COVID-19 outcomes? Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodela, R.; Bregt, A.K.; Ligtenberg, A.; Pérez-Soba, M.; Verweij, P. The social side of spatial decision support systems: Investigating knowledge integration and learning. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 76, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrat-Capdevila, A.; Valdes, J.B.; Gupta, H.V. Decision support systems in water resources planning and management: Stakeholder participation and the sustainable path to science-based decision making. Effic. Decis. Support Syst.-Pract. Chall. Curr. Future 2011, 3, 423–440. [Google Scholar]

- Hettinga, S.; Nijkamp, P.; Scholten, H. A multi-stakeholder decision support system for local neighbourhood energy planning. Energy Policy 2018, 116, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämäläinen, R.; Kettunen, E.; Marttunen, M.; Ehtamo, H. Evaluating a framework for multi-stakeholder decision support in water resources management. Group Decis. Negot. 2001, 10, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantamaneni, K.; Sudha Rani, N.; Rice, L.; Sur, K.; Thayaparan, M.; Kulatunga, U.; Rege, R.; Yenneti, K.; Campos, L.C. A systematic review of coastal vulnerability assessment studies along Andhra Pradesh, India: A critical evaluation of data gathering, risk levels and mitigation strategies. Water 2019, 11, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, F.; Zhu, G.; Ma, C.; Wang, L. Prediction of the COVID-19 spread in African countries and implications for prevention and controls: A case study in South Africa, Egypt, Algeria, Nigeria, Senegal and Kenya. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 729, 138959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayeh, A.; Chami, R. Lifelines in danger. Financ. Dev. 2020, 57, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nicola, M.; Alsafi, Z.; Sohrabi, C.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, M.; Agha, R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 78, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. COVID-19 and Human Development: Assessing the Crisis, Envisioning the Recovery; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Abedi, V.; Olulana, O.; Avula, V.; Chaudhary, D.; Khan, A.; Shahjouei, S.; Li, J.; Zand, R. Racial, economic, and health inequality and COVID-19 infection in the United States. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Cooper, L.A. COVID-19 and health equity—A new kind of “herd immunity”. JAMA 2020, 323, 2478–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunath, N.; Tan, T. The impact of social stratification on morbidity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2020, 40, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldekop, J.A.; Horner, R.; Hulme, D.; Adhikari, R.; Agarwal, B.; Alford, M.; Bakewell, O.; Banks, N.; Barrientos, S.; Bastia, T.; et al. COVID-19 and the case for global development. World Dev. 2020, 134, 105044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Søreide, K.; Hallet, J.; Matthews, J.B.; Schnitzbauer, A.A.; Line, P.D.; Lai, P.B.S.; Otero, J.; Callegaro, D.; Warner, S.G.; Baxter, N.N.; et al. Immediate and long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on delivery of surgical services. Br. J. Surg. 2020, 107, 1250–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, R. Migrant Labour, Informal Economy, and Logistics Sector in a Covid-19 World. In Borders of An Epidemic COVID-19 and Migrant Workers; Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group: Kolkata, India, 2020; pp. 31–41. Available online: https://www.im4change.org/upload/files/Essays%20COVID-19.pdf#page=41 (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- Coibion, O.; Gorodnichenko, Y.; Weber, M. Labor Markets during the Covid-19 Crisis: A Preliminary View; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, T.A.N. Covid-19 Causes of Delays on Construction Projects in Kuwait. IJERGS 2020, 8, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pietromonaco, P.R.; Overall, N.C. Applying relationship science to evaluate how the COVID-19 pandemic may impact couples’ relationships. Am. Psychol. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.T.; Nguyen, D.N.; Beydoun, A.S.; Le, X.T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Pham, Q.T.; Ta, N.T.K.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Nguyen, A.N.; Hoang, M.T. Demand for health information on COVID-19 among Vietnamese. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasnim, S.; Hossain, M.M.; Mazumder, H. Impact of rumors and misinformation on COVID-19 in social media. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2020, 53, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WEF. Challenges and Opportunities in the Post-COVID-19 world. World Economic Forum. May 2020, p. 54. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Challenges_and_Opportunities_Post_COVID_19.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Timmis, K.; Brüssow, H. The COVID-19 pandemic: Some lessons learned about crisis preparedness and management, and the need for international benchmarking to reduce deficits. Environ. Microbiol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, S.; Hasan, K.; Carras, M.C.; Labrique, A. Global Preparedness Against COVID-19: We Must Leverage the Power of Digital Health. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e18980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Global Health Risk Framework: Resilient and Sustainable Health Systems to Respond to Global Infectious Disease Outbreaks; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Ng, C.; Brook, R. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: Big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing. JAMA 2020, 323, 1341–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-Y.; Li, S.-Y.; Yang, C.-H. Initial rapid and proactive response for the COVID-19 outbreak—Taiwan’s experience. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2020, 119, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, I.Y.F. Fighting COVID-19 through government initiatives and collaborative governance: The Taiwan experience. Public Adm. Rev. 2020, 80, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Braund, W.E.; Auerbach, J.; Chou, J.-H.; Teng, J.-H.; Tu, P.; Mullen, J. Policy decisions and use of information technology to fight coronavirus disease, Taiwan. Emerging Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summers, J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Lin, H.-H.; Barnard, L.T.; Kvalsvig, A.; Wilson, N.; Baker, M.G. Potential lessons from the Taiwan and New Zealand health responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Reg. Health Western Pac. 2020, 4, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, K. A Lesson Learned from the Outbreak of COVID-19 in Korea. Indian J. Microbiol. 2020, 60, 396–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.; Heo, K.; Seo, Y. COVID-19 in South Korea: Lessons for developing countries. World Dev. 2020, 135, 105057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J. Lessons from South Korea’s Covid-19 policy response. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 50, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Hwang, C.; Moon, M.J. Policy learning and crisis policy-making: Quadruple-loop learning and COVID-19 responses in South Korea. Policy Soc. 2020, 39, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; An, J.A.-R.; Min, P.-k.; Bitton, A.; Gawande, A.A. How South Korea responded to the COVID-19 outbreak in Daegu. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Choi, G.J.; Ko, H. Information technology–based tracing strategy in response to COVID-19 in South Korea—privacy controversies. JAMA 2020, 323, 2129–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, C. The challenges and opportunities of a global health crisis: The management and business implications of COVID-19 from an Asian perspective. Asian Bus. Manag. 2020, 19, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.L.; Cui, M.; Qian, J. Information resource orchestration during the COVID-19 pandemic: A study of community lockdowns in China. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 54, 102143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuguyo, O.; Kengne, A.P.; Dandara, C. Singapore COVID-19 pandemic response as a successful model framework for low-resource health care settings in Africa? Omics A J. Integr. Biol. 2020, 24, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J. Policy capacity and Singapore’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Policy Soc. 2020, 39, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Zhang, X.; Wu, L.; Zhu, H.; Chen, B. Why do countries respond differently to COVID-19? A comparative study of Sweden, China, France, and Japan. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 50, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zodpey, S.; Negandhi, H.; Dua, A.; Vasudevan, A.; Raja, M. Our fight against the rapidly evolving COVID-19 pandemic: A review of India’s actions and proposed way forward. Indian J. Community Med. 2020, 45, 117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Balogun, J.A. Lessons from the USA Delayed Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Commentary. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2020, 24, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carter, D.P.; May, P.J. Making sense of the US COVID-19 pandemic response: A policy regime perspective. Adm. Theory Prax. 2020, 42, 265–277. [Google Scholar]

- Haffajee, R.L.; Mello, M.M. Thinking globally, acting locally—The US response to COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.U.M.; Safri, S.N.A.; Thevadas, R.; Noordin, N.K.; Abd Rahman, A.; Sekawi, Z.; Ideris, A.; Sultan, M.T.H. COVID-19 Outbreak in Malaysia: Actions Taken by the Malaysian Government. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 97, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, J.M.; Ismail, W.F.N.m.W.; Mohamad, I.; Ab Razak, A.; Harun, A.; Musa, K.I.; Lee, Y.Y. A critical appraisal of COVID-19 in Malaysia and beyond. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 27, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elengoe, A. COVID-19 outbreak in Malaysia. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2020, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, F. The Malaysian Response to COVID-19: Building Preparedness for ‘Surge Capacity’, Testing Efficiency and Containment. 2020. Available online: https://www.europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com/article/125084/the-malaysian-response-to-covid-19-building-preparedness-for-surge-capacity-testing-efficiency-and-containment/ (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Changotra, R.; Rajput, H.; Rajput, P.; Gautam, S.; Arora, A.S. Largest democracy in the world crippled by COVID-19: Current perspective and experience from India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chetterje, P. Gaps in India’s preparedness for COVID-19 control. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, J. A critique of the Indian government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 2020, 47, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulla, P. Covid-19: India imposes lockdown for 21 days and cases rise. BMJ 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Capano, G.; Howlett, M.; Jarvis, D.S.; Ramesh, M.; Goyal, N. Mobilizing policy (in) capacity to fight COVID-19: Understanding variations in state responses. Policy Soc. 2020, 39, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, G.P.; Sadun, R.; Zanini, M. Lessons from Italy’s Response to Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=57971 (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Ruiu, M.L. Mismanagement of Covid-19: Lessons learned from Italy. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 1007–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armocida, B.; Formenti, B.; Ussai, S.; Palestra, F.; Missoni, E. The Italian health system and the COVID-19 challenge. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 5, e253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, C.; Antonini, M.; Genie, M.G.; Cotugno, G.; Lanteri, A.; Melia, A.; Paolucci, F. The COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: Policy and technology impact on health and non-health outcomes. Health Policy Technol. 2020, 9, 454–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterlini, M. On the front lines of coronavirus: The Italian response to covid-19. BMJ 2020, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakir, C. The Turkish state’s responses to existential COVID-19 crisis. Policy Soc. 2020, 39, 424–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyanak, O. Faith, politics and the COVID-19 pandemic: The Turkish Response. Med. Anthropol. 2020, 1745482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zahariadis, N.; Petridou, E.; Oztig, L.I. Claiming credit and avoiding blame: Political accountability in Greek and Turkish responses to the COVID-19 crisis. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2020, 6, 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Desson, Z.; Weller, E.; McMeekin, P.; Ammi, M. An analysis of the policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in France, Belgium, and Canada. Health Policy Technol. 2020, 9, 430–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detsky, A.S.; Bogoch, I.I. COVID-19 in Canada: Experience and response. JAMA 2020, 324, 743–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaivanov, A.; Lu, S.E.; Shigeoka, H.; Chen, C.; Pamplona, S. Face Masks, Public Policies and Slowing the Spread of COVID-19: Evidence from Canada. MedRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, M.; Fadaak, R.; Davies, J.; Blaak, J.; Forest, P.; Green, L.; Conly, J. Integrating the social sciences into the COVID-19 response in Alberta, Canada. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounie, D.; Camara, Y.; Galbraith, J.W. Consumers’ Mobility, Expenditure and Online-Offline Substitution Response to COVID-19: Evidence from French Transaction Data. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3588373 (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Barro, K.; Malone, A.; Mokede, A.; Chevance, C. Management of the COVID-19 epidemic by public health establishments–Analysis by the Fédération Hospitalière de France. J. Visc. Surg. 2020, 157, S19–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, L.; Pullano, G.; Sabbatini, C.E.; Boëlle, P.-Y.; Colizza, V. Impact of lockdown on COVID-19 epidemic in Île-de-France and possible exit strategies. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullano, G.; Valdano, E.; Scarpa, N.; Rubrichi, S.; Colizza, V. Population mobility reductions during COVID-19 epidemic in France under lockdown. MedRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWit, A.; Shaw, R.; Djalante, R. An integrated approach to sustainable development, National Resilience, and COVID-19 responses: The case of Japan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, A.; Grubaugh, N.D. Why does Japan have so few cases of COVID-19? EMBO Mol. Med. 2020, 12, e12481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tashiro, A.; Shaw, R. COVID-19 pandemic response in Japan: What is behind the initial flattening of the curve? Sustainability 2020, 12, 5250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabe, T.; Tsubouchi, K.; Fujiwara, N.; Wada, T.; Sekimoto, Y.; Ukkusuri, S.V. Non-compulsory measures sufficiently reduced human mobility in Japan during the COVID-19 epidemic. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.09423. [Google Scholar]

- Pacces, A.M.; Weimer, M. From Diversity to Coordination: A European Approach to COVID-19. Eur. J. Risk Regul. 2020, 11, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dahlberg, M.; Edin, P.-A.; Grönqvist, E.; Lyhagen, J.; Östh, J.; Siretskiy, A.; Toger, M. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on population mobility under mild policies: Causal evidence from Sweden. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.09087. [Google Scholar]

- Kavaliunas, A.; Ocaya, P.; Mumper, J.; Lindfeldt, I.; Kyhlstedt, M. Swedish policy analysis for Covid-19. Health Policy Tech. 2020, 9, 598–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petridou, E. Politics and administration in times of crisis: Explaining the Swedish response to the COVID-19 crisis. Eur. Policy Anal. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeriani, G.; Sarajlic Vukovic, I.; Lindegaard, T.; Felizia, R.; Mollica, R.; Andersson, G. Addressing Healthcare Gaps in Sweden during the COVID-19 Outbreak: On Community Outreach and Empowering Ethnic Minority Groups in a Digitalized Context. Healthcare 2020, 8, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, N. Covid-19: Why Germany’s case fatality rate seems so low. BMJ 2020, 369, m1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Armbruster, S.; Klotzbü, V. Lost in Lockdown? Covid-19, Social Distancing, and Mental Health in Germany; Discussion Series No. 2020-04; Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg: Freiburg i. Br, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/218885 (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Buthe, T.; Messerschmidt, L.; Cheng, C. Policy responses to the coronavirus in Germany. In The World Before and After COVID-19: Intellectual Reflections on Politics, Diplomacy and International Relations; Gardini, G.L., Ed.; European Institute of International Relations: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Desson, Z.; Lambertz, L.; Peters, J.W.; Falkenbach, M.; Kauer, L. Europe’s Covid-19 outliers: German, Austrian and Swiss policy responses during the early stages of the 2020 pandemic. Health Policy Tech. 2020, 9, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narlikar, A. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Germany’s response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Daring. Available online: https://www.orfonline.org/research/the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly-germanys-response-to-the-covid-19-pandemic-66487 (accessed on 30 March 2020).

- Naumann, E.; Möhring, K.; Reifenscheid, M.; Wenz, A.; Rettig, T.; Lehrer, R.; Krieger, U.; Juhl, S.; Friedel, S.; Fikel, M. COVID-19 policies in Germany and their social, political, and psychological consequences. Eur. Policy Anal. 2020, 6, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.G.; Kvalsvig, A.; Verrall, A.J.; Wellington, N. New Zealand’s COVID-19 elimination strategy. Med. J. Aust. 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.G.; Kvalsvig, A.; Verrall, A.J.; Telfar-Barnard, L.; Wilson, N. New Zealand’s elimination strategy for the COVID-19 pandemic and what is required to make it work. N. Z. Med. J. 2020, 133, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M.G.; Wilson, N.; Anglemyer, A. Successful elimination of Covid-19 transmission in New Zealand. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, S. New zealand eliminates covid-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferies, S.; French, N.; Gilkison, C.; Graham, G.; Hope, V.; Marshall, J.; McElnay, C.; McNeill, A.; Muellner, P.; Paine, S. COVID-19 in New Zealand and the impact of the national response: A descriptive epidemiological study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e612–e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, C.R.; Sah, P.; Moghadas, S.M.; Pandey, A.; Shoukat, A.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Meyers, L.A.; Singer, B.H.; Galvani, A.P. Impact of international travel and border control measures on the global spread of the novel 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 7504–7509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Now, India bans entry of Indians from EU, Turkey and UK. The Economic Times. 18 March 2020. Available online: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/government-prohibits-entry-of-passengers-from-eu-turkey-uk-from-march-18/articleshow/74657194.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Zangrillo, A.; Beretta, L.; Silvani, P.; Colombo, S.; Scandroglio, A.M.; Dell’Acqua, A.; Fominskiy, E.; Landoni, G.; Monti, G.; Azzolini, M.L. Fast reshaping of intensive care unit facilities in a large metropolitan hospital in Milan, Italy: Facing the COVID-19 pandemic emergency. Crit. Care Resusc. 2020, 22, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, N.; Cheng, K.-W.; Qamar, N.; Huang, K.-C.; Johnson, J.A. Weathering COVID-19 storm: Successful control measures of five Asian countries. Am. J. Infect. Control 2020, 48, 851–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åslund, A. Responses to the COVID-19 crisis in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2020, 61, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopman, J.; Allegranzi, B.; Mehtar, S. Managing COVID-19 in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JAMA 2020, 323, 1549–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peto, J.; Alwan, N.A.; Godfrey, K.M.; Burgess, R.A.; Hunter, D.J.; Riboli, E.; Romer, P.; Buchan, I.; Colbourn, T.; Costelloe, C. Universal weekly testing as the UK COVID-19 lockdown exit strategy. Lancet 2020, 395, 1420–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, K.O.; Lai, F.; Wei, V.W.I.; Tsoi, M.T.F.; Wong, S.Y.S.; Tang, J. Comparing the impact of various interventions to control the spread of COVID-19 in twelve countries. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 106, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djalante, R.; Lassa, J.; Setiamarga, D.; Mahfud, C.; Sudjatma, A.; Indrawan, M.; Haryanto, B.; Sinapoy, M.S.; Rafliana, I.; Djalante, S. Review and analysis of current responses to COVID-19 in Indonesia: Period of January to March 2020. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanezi, F.; Aljahdali, A.; Alyousef, S.; Alrashed, H.; Alshaikh, W.; Mushcab, H.; Alanzi, T. Implications of Public Understanding of COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia for Fostering Effective Communication Through Awareness Framework. Front. Public Health 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzigbede, K.; Gehl, S.B.; Willoughby, K. Disaster resiliency of US local governments: Insights to strengthen local response and recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, A.F.; BaniMustafa, A.A.; Alessa, Y.M.; Almutairi, S.B.; Almaleh, Y. Public trust and compliance with the precautionary measures against COVID-19 employed by authorities in Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, K.; Khajanchi, S.; Nieto, J.J. Modeling and forecasting the COVID-19 pandemic in India. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 139, 110049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, N.-C.; Chi, H.; Tai, Y.-L.; Peng, C.-C.; Tseng, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-C.; Tan, B.F.; Lin, C.-Y. Impact of Wearing Masks, Hand Hygiene, and Social Distancing on Influenza, Enterovirus, and All-Cause Pneumonia During the Coronavirus Pandemic: Retrospective National Epidemiological Surveillance Study. J. Med. Internet. Res. 2020, 22, e21257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancet, T. India under COVID-19 lockdown. Lancet 2020, 395, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, K.-M.; Ho, L.K.-K.; Wong, N.W.; Chiu, A. Fighting COVID-19 in Hong Kong: The effects of community and social mobilization. World Dev. 2020, 134, 105055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartley, K.; Jarvis, D.S. Policymaking in a low-trust state: Legitimacy, state capacity, and responses to COVID-19 in Hong Kong. Policy Soc. 2020, 39, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.L. COVID-19 and Global Governance. J. Manag. Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, D.; Casady, C.B. A Coronavirus (COVID-19) Triage Framework for (Sub) national Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Programs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Policy Responses to COVID19. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19 (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Katz, J.; Lu, D.; Sanger-Katz, M. USA: Excess death data compared to confirmed COVID-19 fatalities. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/01/14/us/covid-19-death-toll.html (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Leonardo, L.; Xavier, R. The End of Social Confinement and COVID-19 Re-Emergence Risk. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 746–755. [Google Scholar]

- Tackling Coronavirus (COVID 19) Contributing to a Global Effort. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/ (accessed on 16 July 2020).

- Tabish, S. COVID-19 Pandemic: The crisis and the longer-term perspectives. J. Cardiol. Curr. Res. 2020, 13, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Development Outlook 2020: Achieving SDGs in the Wake of COVID-19: Scenarios for Policymakers. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/sustainable-development-outlook-2020-achieving-sdgs-in-the-wake-of-covid-19-scenarios-for-policymakers/ (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- World Bank Group Launches First Operations for COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Emergency Health Support, Strengthening Developing Country Responses. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/04/02/world-bank-group-launches-first-operations-for-covid-19-coronavirus-emergency-health-support-strengthening-developing-country-responses (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Haghani, M.; Bliemer, M.C.; Goerlandt, F.; Li, J. The scientific literature on Coronaviruses, COVID-19 and its associated safety-related research dimensions: A scientometric analysis and scoping review. Saf. Sci. 2020, 129, 104806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maor, M. The political calculus of bad governance: Governance choices in response to the first wave of COVID-19 in Israel. In Proceedings of the ECPR General Conference Online, Colchester, UK, 24–28 August 2020; pp. 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bouey, J. Strengthening China’s Public Health Response System: From SARS to COVID-19. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 939–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermann, C. Epistemic ignorance, poverty and the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Bioeth. Rev. 2020, 12, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onder, G.; Rezza, G.; Brusaferro, S. Case-Fatality Rate and Characteristics of Patients Dying in Relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA 2020, 323, 1775–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marahatta, S.B.; Paudel, S.; Aryal, N. COVID-19 Pandemic: What can Nepal do to Curb the Potential Public Health Disaster? J. Karnali Acad. Health Sci. 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.; Walker, J. The Promise and Challenge of Home Health Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. Fam. Physician 2020, 102, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bielicki, J.A.; Duval, X.; Gobat, N.; Goossens, H.; Koopmans, M.; Tacconelli, E.; van der Werf, S. Monitoring approaches for health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, e261–e267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, V.; Restrepo, A.M.H.; Preziosi, M.-P.; Swaminathan, S. Data sharing for novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Bull. World Health Organ. 2020, 98, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, W.; Trump, B.; Love, P.; Linkov, I. Bouncing forward: A resilience approach to dealing with COVID-19 and future systemic shocks. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2020, 40, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paganini, N.A.K.; Buthelezi, N.; Harris, D.; Lemke, S.; Luis, A.; Koppelin, J.; Karriem, A.; Ncube, F.; Nervi Aguirre, E.; Ramba, T.; et al. Growing and Eating Food during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Farmers’ Perspectives on Local Food System Resilience to Shocks in Southern Africa and Indonesia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentilini, U.; Almenfi, M.; Orton, I.; Dale, P. Social Protection and Jobs Responses to COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33635 (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Xu, B.; Gutierrez, B.; Mekaru, S.; Sewalk, K.; Goodwin, L.; Loskill, A.; Cohn, E.L.; Hswen, Y.; Hill, S.C.; Cobo, M.M. Epidemiological data from the COVID-19 outbreak, real-time case information. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.R.; Apu, E.H.; Shahabuddin, S.; Shams, A.B.; Kabir, R. Overview of digital health surveillance system during COVID-19 pandemic: Public health issues and misapprehensions. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.13633. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, S.E.; Wenham, C. Why the COVID-19 response needs International Relations. Int. Aff. 2020, 96, 1227–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.-Q.; Yang, L.; Zhou, P.-X.; Li, H.-B.; Liu, F.; Zhao, R.-S. Recommendations and guidance for providing pharmaceutical care services during COVID-19 pandemic: A China perspective. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1819–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelyn, C.D.V.; Viljoen, I.M.; Dhai, A.; PEPPER, M.; Naidu, C. Resource allocation during COVID-19: A focus on vulnerable populations. S. Afr. J. Bioeth. Law 2020, 13, 83. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Q.; Schwarz, S.; Schwarz, G. Responding to COVID-19: Community volunteerism and coproduction in China. World Dev. 2020, 137, 105128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanica, A.; Fossat, Y. COVID-19 has inspired global healthcare innovation. Can. J. Public Health 2020, 111, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Kupferschmidt, K. Countries Test Tactics in ‘War’ against COVID-19; American Association for the Advancement of Science: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Siddique, R.; Ali, A.; Xue, M.; Nabi, G. Novel coronavirus, poor quarantine, and the risk of pandemic. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 104, 449–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, D.; Casady, C.B. Encouraging and Procuring Healthcare Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) Through Unsolicited Proposals during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic; ResearchGate: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Meinzen-Dick, R. Collective action and “social distancing” in COVID-19 responses. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 649–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanto, D.; Akrim, A. Covid-19 Pandemic: A Social Welfare Perspective. Soc. Sci. Humanit. J. 2020, 4, 1915–1924. [Google Scholar]

- Megahed, N.A.; Ghoneim, E.M. Antivirus-built environment: Lessons learned from Covid-19 pandemic. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 61, 102350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanarosa, P.B.; Bauchner, H. COVID-19—looking beyond tomorrow for health care and society. JAMA 2020, 323, 1907–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinwehr, U. Facing COVID-19, World Health Organization in crisis mode. DW News, 18 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Laxminarayan, R.; Reif, J.; Malani, A. Incentives for reporting disease outbreaks. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huttner, B.; Catho, G.; Pano-Pardo, J.R.; Pulcini, C.; Schouten, J. COVID-19: Don’t neglect antimicrobial stewardship principles! Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 808–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kost, G.J. Geospatial spread of antimicrobial resistance, bacterial and fungal threats to COVID-19 survival, and point-of-care solutions. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthiessen, L.; Colli, W.; Delfraissy, J.-F.; Hwang, E.-S.; Mphahlele, J.; Ouellette, M. Coordinating funding in public health emergencies. Lancet 2016, 387, 2197–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygren-Krug, H. The Right(s) Road to Universal Health Coverage. Health Hum Rights 2019, 21, 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization; OECD; International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Delivering Quality Health Services: A Global Imperative for Universal Health Coverage; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Universal Health Coverage: Moving Together to Build a Healthier World. Available online: https://www.un.org/pga/73/event/universal-health-coverage/ (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Baum, M.; Ognyanova, K.; Lazer, D.; Della Volpe, J.; Perlis, R.H.; Druckman, J.; Santillana, M. The state of the nation: A 50-state covid-19 survey report# 3 vote by mail. OSFPREPRINTS 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, W. We Can’t Let Coronavirus Tear Us Apart. Available online: https://www.hollandsentinel.com/opinion/20200313/wendy-sherman-we-cant-let-coronavirus-tear-us-apart (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- How the Public Sector and Civil Society Can Respond to the Coronavirus Pandemic. Available online: https://www.hks.harvard.edu/faculty-research/policy-topics/health/how-public-sector-and-civil-society-can-respond-coronavirus (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Lele, U.; Bansal, S.; Meenakshi, J. Health and Nutrition of India’s Labour Force and COVID-19 Challenges. Econ. Political Weekly 2020, 55, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, R.; Smith, R. Rituals of global health: Negotiating the world health assembly. Glob. Public Health 2019, 14, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wahid, M.A.K.; Nurhaeni, I.D.A.; Suharto, D.G. The Synergy among Stakeholders in Management of Village-Owned Enterprises (BUM Desa); 1st Borobudur International Symposium on Humanities, Economics and Social Sciences (BIS-HESS 2019); Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uusikylä, P.; Tommila, P.; Uusikylä, I. Disaster Management as a Complex System: Building Resilience with New Systemic Tools of Analysis. In Society as an Interaction Space; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 161–190. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan, K.M.W.; Shi, S.Y.; Nabbijohn, A.N.; MacMullin, L.N.; VanderLaan, D.P.; Wong, W.I. Children’s appraisals of gender nonconformity: Developmental pattern and intervention. Child Dev. 2020, 91, e780–e798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; Akhter, S.; Zizi, F.; Jean-Louis, G.; Ramasubramanian, C.; Edward Freeman, R.; Narasimhan, M. Project Stakeholder Management in the Clinical Research Environment: How to Do it Right. Front. Psychiatry 2015, 6, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rice, L.; Sara, R. Updating the determinants of health model in the Information Age. Health Promot. Int. 2018, 34, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oliver, N.; Lepri, B.; Sterly, H.; Lambiotte, R.; Deletaille, S.; De Nadai, M.; Letouzé, E.; Salah, A.A.; Benjamins, R.; Cattuto, C.; et al. Mobile phone data for informing public health actions across the COVID-19 pandemic life cycle. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc0764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, C.; Pearlman, C.V.; Tulika Singh, L.M.; Stevens, B.K. Multi-stakeholder partnerships: Breaking down barriers to effective cancer-control planning and implementation in low-and middle-income countries. Sci. Dipl. 2016, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, A.A.; Shaw, G.P. Academic Leadership in a Time of Crisis: The Coronavirus and COVID-19. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2020, 14, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country/Territory | Method/Approach | Crisis Management | Partners/Stakeholders | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taiwan | Networking, proactive testing, border control, transparency | Frequent health check-ups, public education, relief to business, use of information technology | Multi-layer governance, private organisations, insurance companies, citizens | [40,41,42,43,44] |

| South Korea | Timely emergency response, the nationwide framework of networks among stakeholders | Shared interest, priority-based emergency response, rapid response, effective anti-COVID-19 measures, rapid testing, effective isolation strategy, scaling up resources, use of information technology | Govt, community, CSOs (Civil Society Organisation) | [45,46,47,48,49,50] |

| China, Singapore | The collaboration of Science including Social Sciences | Large scale coordination, institutional timely response, community resilience, national level response, effective contact tracing | Govt, industry, banks and financial institutions | [51,52,53,54,55] |

| USA | Networking | Outbreak management, control, ineffective response to the COVID-19 | Multi-layer Govts, private, CSOs | [56,57,58,59] |

| Malaysia | Movement control order | Produce PPE (personal, protective equipment), fundraising, collaboration with healthcare service providers, inducting additional Labs, effective testing and contact tracing, effective communication and daily briefings | Govt, CSOs, community | [60,61,62,63] |

| India | Lockdown | Emergency management, interstate transmission control, laboratory network, ineffective practice of physical distancing, closure of educational institutes | Multi-layer Govts, private, CSOs | [56,64,65,66,67] |

| Italy | Pandemic management, lockdown | Institutional arrangements, undermining the virus, triple “Ts” (testing, tracing and treatment) | Govt, CSOs | [68,69,70,71,72,73] |

| Turkey | Lockdown, proactive policy style | Rapid and strong response, extensive use of institutional resources, factual information campaigns | Presidential system of government, community, religious authorities | [74,75,76] |

| Canada | Social distancing, travel restrictions, integration of social sciences | Well-functioning federalism, long term care, rapid testing and tracing, face mask mandates | Multilayer government | [77,78,79,80] |

| France | Nationwide lockdown | Closure of non-essential public places and services, internal and international travel restrictions, cancellation of public events, all covid-19 system—care categorization and anticipation strategy | Govt, health department | [55,81,82,83,84] |

| Japan | Emergency (sub-national and local) | Effective implementation of self-discipline, avoiding “Three Cs” (closed spaces with insufficient ventilation, crowded conditions with people, and conversations at a short distance), no lockdown, recommendations regarding closure of schools and work places, public information campaigns | Govt, community | [40,55,85,86,87,88] |

| Sweden | Pandemic management—long term plan | Temporary ban on nonessential travel, recommendations on social distancing and working online, voluntary self-protection, non-closure of gyms, schools, restaurants and shops | Govt, voluntary organizations, community | [55,89,90,91,92,93] |

| Germany | Social lockdown & Economic lockdown | Nation–wide social distancing and contact restrictions, personal care business centres were closed (hair dresses, tattoos, massage centres, etc.), different states followed different styles of lockdown e.g., strict lockdown—stay at home order and/or lenient lockdown—not to leave the house without a reason, closure of churches, recommendation on wearing of face masks, good medical preparedness, developed a reliable testing system, stock of testing kits, early testing and tracing | Govt (National & Federal state), public and private hospitals, medical professionals, virologists, public health experts, laboratories, community, self-discipline, citizens | [94,95,96,97,98,99] |

| New Zealand | Lockdown | Lockdown measures, closure of schools, non-essential workplaces, travel restrictions, restrictions on social gathering, social distancing, border control, rapid and science-based risk assessment, rapid testing and contact tracing, community transmission control measures, promotion of hand washing hygiene, medical preparedness, arranged more ICU & ventilator facilities, safeguarding healthcare professionals | Govt, public and private hospitals, medical professionals, virologists, public health experts, laboratories, community, self-discipline, citizens | [100,101,102,103,104] |

| International travel restrictions [105,106] |

| Improving health facilities [107] |

| Strict quarantine measures [108,109,110] |

| Tracking and testing [47,108,111,112,113] |

| Built new hospitals for the treatment COVID-19 [110] |

| Building up advisory systems and Creating public awareness [47,114] |

| Stoppage of Non-essential businesses [108,112] |

| Strengthening Government services [115,116] |

| Restriction on mass gathering [108,112,116] |

| School and university closure [108,109,112,116] |

| Curfew [109,112,117] |

| Health data management/ epidemiological data base [47,108,114] |

| State of emergency [108] |

| Internal travel restriction [112] |

| Lockdown policy [111,112,117,118,119] |

| Decentralised communication [47] |

| community to be proactive, sharing of responsibility [120,121] |

| Stakeholders and clinical manifestation of COVID-19 [45,122] |

| Lessons Learned from the Experience of Different Countries |

|---|

| 1. Strengthen crisis management and response strategies [133] |

| 2. Recognize your cognitive biases [134] |

| 3. Avoid partial solutions [69] |

| 4. Learning is critical [48] |

| 5. Extensive testing of symptomatic and asymptomatic cases early on [135] |

| 6. Proactive tracking of potential positives [136] |

| 7. A strong emphasis on home diagnosis and care [137] |

| 8. Specific efforts to monitor and protect health care and other essential workers [138] |

| 9. Collecting and disseminating data is important [139] |

| 10. The resilience of affected/infected individuals [140] |

| 11. Awareness of the plight of farmers, labours [141] |

| 12. Social protection measures [142] |

| 13. A robust collection of health data, and epidemiological database (for health policies) [143] |

| 14. To ensure public health surveillance [144] |

| 15. Recognition of the role of international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) [145] |

| 16. Timely provision of medical supplies and hygiene kit [146] |

| 17. Provision of social support and care to the appropriate communities and vulnerable populations [147] |

| 18. Coordination of funding activities and volunteers [148] |

| 19. R&D in life-saving medical innovations [149] |

| 20. Test, Test and Test again [150] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Panneer, S.; Kantamaneni, K.; Pushparaj, R.R.B.; Shekhar, S.; Bhat, L.; Rice, L. Multistakeholder Participation in Disaster Management—The Case of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2021, 9, 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9020203

Panneer S, Kantamaneni K, Pushparaj RRB, Shekhar S, Bhat L, Rice L. Multistakeholder Participation in Disaster Management—The Case of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare. 2021; 9(2):203. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9020203

Chicago/Turabian StylePanneer, Sigamani, Komali Kantamaneni, Robert Ramesh Babu Pushparaj, Sulochana Shekhar, Lekha Bhat, and Louis Rice. 2021. "Multistakeholder Participation in Disaster Management—The Case of the COVID-19 Pandemic" Healthcare 9, no. 2: 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9020203