Understanding Why All Types of Motivation Are Necessary in Advanced Anaesthesiology Training Levels and How They Influence Job Satisfaction: Translation of the Self-Determination Theory to Healthcare

Abstract

1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Outcomes

Situational Motivation Scale

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

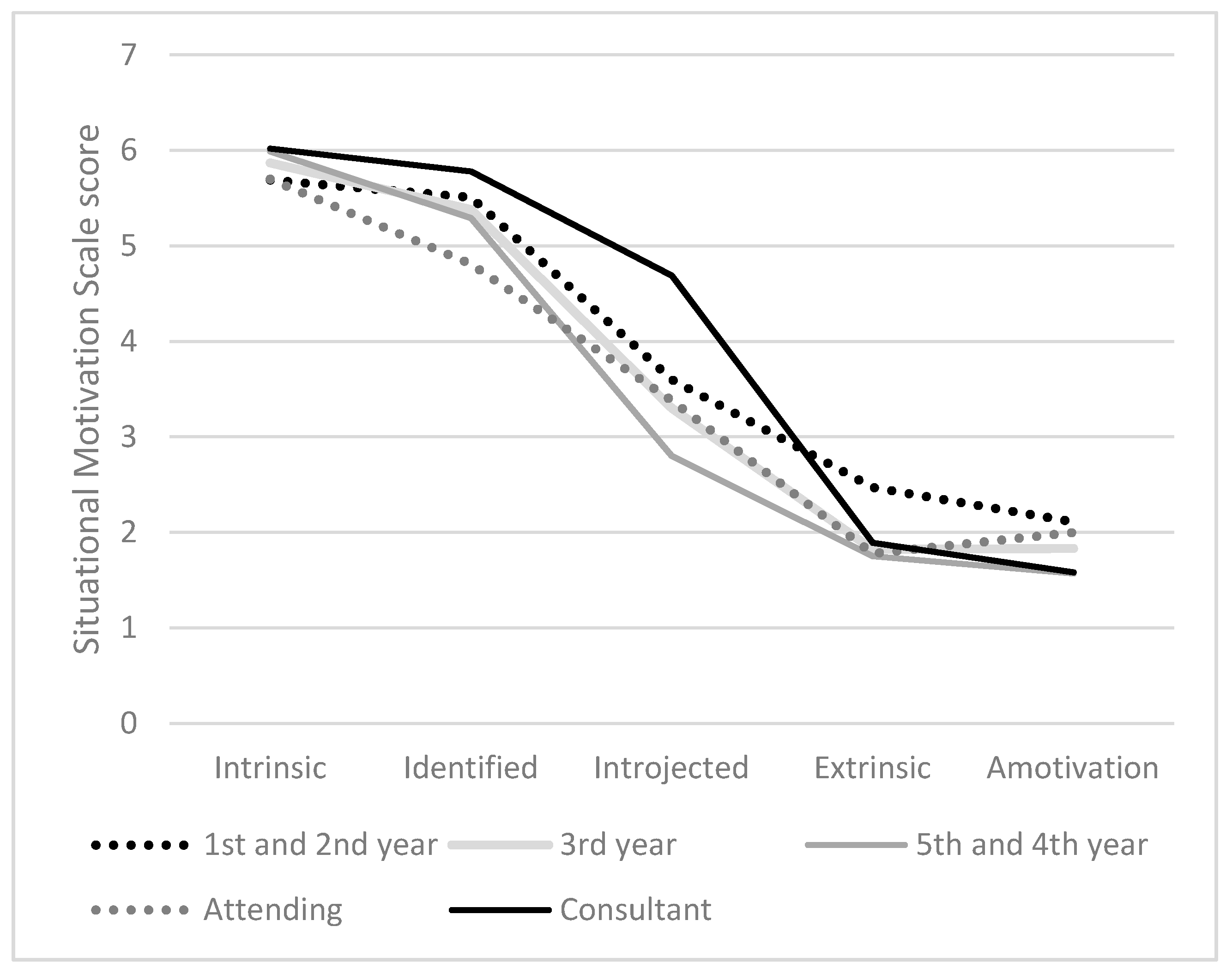

3.1. Situational Motivation

3.2. Correlation of Situational Motivation and Job Satisfaction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schlitzkus, L.L.; Schenarts, K.D.; Schenarts, P.J. Is Your Residency Program Ready for Generation Y? J. Surg. Educ. 2010, 67, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuri, R.N.D.K.; Senkubuge, F.; Hongoro, C. Determinants of Motivation among Healthcare Workers in the East African Community between 2009–2019: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2020, 8, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richer, S.F.; Blanchard, C.; Vallerand, R.J. A Motivational Model of Work Turnover. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 2089–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, A.; Fernando, S.; Bottiglieri, T. The effect of organisational factors in motivating healthcare employees: A systematic review. Br. J. Health Manag. 2018, 24, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, K.L.; Masatu, M.C. Using the Hawthorne effect to examine the gap between a doctor’s best possible practice and actual performance. J. Dev. Econ. 2010, 93, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.C.; Saizow, R.B.; Ryan, R.M. The importance of self-determination theory for medical education. Acad. Med. 1999, 74, 992–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory in health care and its relations to motivational interviewing: A few comments. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N. Motivational clusters in a sample of British physical education classes. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2002, 3, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.J.; Biddle, S.J. Young People’s Motivational Profiles in Physical Activity: A Cluster Analysis. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2001, 23, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Eghrari, H.; Patrick, B.C.; Leone, D.R. Facilitating Internalization: The Self-Determination Theory Perspective. J. Pers. 1994, 62, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koestner, R.; Losier, G.F. Distinguishing three ways of being highly motivated: A closer look at introjection, identification, and intrinsic motivation. In Handbook of Self-Determination Research; Deci, E.L., Ryan, R.M., Eds.; University of Rochester Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 101–121. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Fortier, M.S.; Guay, F. Self-determination and persistence in a real-life setting: Toward a motivational model of high school dropout. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 72, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baard, P.P. Intrinsic need satisfaction in organizations: A motivational basis of success in for-profit and not-for-profit settings. Handb. Self-Determ. Res. 2002, 2, 255–275. [Google Scholar]

- Baard, P.P.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Need Satisfaction: A Motivational Basis of Performance and Weil-Being in Two Work Settings 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 2045–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, J.; Pierce, W.D.; Banko, K.M.; Gear, A. Achievement-Based Rewards and Intrinsic Motivation: A Test of Cognitive Mediators. J. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 97, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Koestner, R.; Ryan, R.M. A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N.; Vallerand, R.J.; Lafrenière, M.-A.K.; Bureau, J.S. The mediating role of positive and negative affect in the situational motivation-performance relationship. Motiv. Emot. 2013, 37, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J. Self-determination theory applied to educational settings. Handb. Self-Determ. Res. 2002, 2, 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Connell, J.P. Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Grolnick, W.S. Origins and pawns in the classroom: Self-report and projective assessments of individual differences in children’s perceptions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 50, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M. Motivation and creativity: Effects of motivational orientation on creative writers. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 48, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Blssonnette, R. Intrinsic, Extrinsic, and Amotivational Styles as Predictors of Behavior: A Prospective Study. J. Pers. 1992, 60, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benware, C.A.; Deci, E.L. Quality of learning with an active versus passive motivational set. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1984, 21, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilardi, B.C.; Leone, D.; Kasser, T.; Ryan, R.M. Employee and Supervisor Ratings of Motivation: Main Effects and Discrepancies Associated with Job Satisfaction and Adjustment in a Factory Setting 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 23, 1789–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theorell, T.; Karasek, R.; Eneroth, P. Job strain variations in relation to plasma testosterone fluctuations in working men—a longitudinal study. J. Intern. Med. 1990, 227, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteson, M.T.; Ivancevich, J.M. Controlling Work Stress: Effective Human Resource and Management Strategies; Jossey-Bass: San Franciso, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, L.W.; Gartin, P.R.; Buerger, M.E. Hot Spots of Predatory Crime: Routine Activities and the Criminology of Place. Criminology 1989, 27, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L.; Grolnick, W.S. Autonomy, relatedness, and the self: Their relation to development and psychopathology. Ariel 1995, 128, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Fernet, C.; Guay, F.; Senécal, C. Adjusting to job demands: The role of work self-determination and job control in predicting burnout. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 65, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernet, C.; Senécal, C.; Guay, F.; Marsh, H.; Dowson, M. The Work Tasks Motivation Scale for Teachers (WTMST). J. Career Assess. 2008, 16, 256–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernet, C.; Gagné, M.; Austin, S. When does quality of relationships with coworkers predict burnout over time? The moderating role of work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 1163–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J.E.; Judge, T.A. Self-concordance at work: Toward understanding the motivational effects of transformational leaders. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 554–571. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Coggins, R.; Rosekind, M.R.; Hurd, S.; Buccino, K.R. Relationship of day versus night sleep to physician performance and mood. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1994, 24, 928–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazelle, G.; Liebschutz, J.M.; Riess, H. Physician Burnout: Coaching a Way Out. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, G.S.; Ahmad, S.; Stock, M.C.; Harter, R.L.; Almeida, M.D.; Fitzgerald, P.C.; McCarthy, R.J. High incidence of burnout in academic chairpersons of anesthesiology: Should we be taking better care of our leaders? J. Am. Soc. Anesthesiol. 2011, 114, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyman, S.A.; Michaels, D.R.; Berry, J.M.; Schildcrout, J.S.; Mercaldo, N.D.; Weinger, M.B. Risk of burnout in perioperative clinicians: A survey study and literature review. J. Am. Soc. Anesthesiol. 2011, 114, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zuo, M.; Gelb, A.W.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, X.; Yao, D.; Xia, D.; Huang, Y. Chinese anesthesiologists have high burnout and low job satisfaction: A cross-sectional survey. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1004–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job Burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, M.T.; Townend, K.; Laidlaw, T. Job satisfaction, stress and burnout in Australian specialist anaesthetists. Anaesthesia 2003, 58, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt, T. Burnout in anesthesiology: A call to action. J. Am. Soc. Anesthesiol. 2011, 114, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyssen, A.-S.; Hansez, I. Stress and burnout in anaesthesia. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2008, 21, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiron, B.; Michinov, E.; Olivier-Chiron, E.; Laffon, M.; Rusch, E. Job Satisfaction, Life Satisfaction and Burnout in French Anaesthetists. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 948–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ádám, S.; Györffy, Z.; Susánszky, É. Physician burnout in Hungary: A potential role for work—Family conflict. J. Health Psychol. 2008, 13, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, C.L.; Clarke, S.; Rowbottom, A.M. Occupational stress, job satisfaction and well-being in anaesthetists. Stress Med. 1999, 15, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindfors, P.M.; Nurmi, K.E.; Meretoja, O.A.; Luukkonen, R.A.; Viljanen, A.-M.; Leino, T.J.; Härmä, M.I. On-call stress among Finnish anaesthetists. Anaesthesia 2006, 61, 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, A.; Maia, P.; Azevedo, A.; Amaral, C.; Tavares, J. Stress and burnout among Portuguese anaesthesiologists. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2006, 23, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinke, W.; Dunkel, P.; Brähler, E.; Nübling, M.; Riedel-Heller, S.; Kaisers, U. Burnout in anesthesiology and intensive care: Is there a problem in Germany? Der Anaesthesist 2011, 60, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balch, C.M.; Shanafelt, T.S. Dynamic Tension between Success in a Surgical Career and Personal Wellness: How Can We Succeed in a Stressful Environment and a “Culture of Bravado”? Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 18, 1213–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Balch, C.M.; Bechamps, G.; Russell, T.; Dyrbye, L.; Satele, D.; Collicott, P.; Novotny, P.J.; Sloan, J.; Freischlag, J. Burnout and Medical Errors among American Surgeons. Ann. Surg. 2010, 251, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.S.; Skinner, A.C. Outcomes of Physician Job Satisfaction: A Narrative Review, Implications, and Directions for Future Research. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheurer, D.; Mckean, S.; Miller, J.; Wetterneck, T.U.S. physician satisfaction: A systematic review. J. Hosp. Med. 2009, 4, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, K.S.; Collins, S.K.; McKinnies, R.; Jensen, S. Employee satisfaction and employee retention: Catalysts to patient satisfaction. Health Care Manag. 2008, 27, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, S. Hand in hand: Patient and employee satisfaction. Trustee J. Hosp. Gov. Boards 2005, 58, 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lebbin, M. Back to basics 2. How satisfied are your employees? Making the employee/patient satisfaction connection. Trustee J. Hosp. Gov. Boards 2007, 60, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rama-Maceiras, P.; Parente, S.; Kranke, P. Job satisfaction, stress and burnout in anaesthesia: Relevant topics for anaesthesiologists and healthcare managers? Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2012, 29, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, A.; Graham, J.; Richards, M.; Gregory, W.; Cull, A. Mental health of hospital consultants: The effects of stress and satisfaction at work. Lancet 1996, 347, 724–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M.R.; Smets, E.M.; Oort, F.J.; De Haes, H.C. Stress, satisfaction and burnout among Dutch medical specialists. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2003, 168, 271–275. [Google Scholar]

- Lederer, W.; Kinzl, J.F.; Trefalt, E.; Traweger, C.; Benzer, A. Significance of working conditions on burnout in anesthetists. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2006, 50, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzl, J.F.; Knotzer, H.; Traweger, C.; Lederer, W.; Heidegger, T.; Benzer, A. Influence of working conditions on job satisfaction in anaesthetists. Br. J. Anaesth. 2005, 94, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, A.C.L.; Irwin, M.G.; Lee, P.W.H.; Lee, T.H.W.; Man, S.F. Comparison of Stress in Anaesthetic Trainees between Hong Kong and Victoria, Australia. Anaesth. Intensive Care 2008, 36, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knörzer, L.; Brünken, R.; Park, B. Facilitators or suppressors: Effects of experimentally induced emotions on multimedia learning. Learn. Instr. 2016, 44, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, F.; Vallerand, R.J.; Blanchard, C. On the Assessment of Situational Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation: The Situational Motivation Scale (SIMS). Motiv. Emot. 2000, 24, 175–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dula, D.J.; Dula, N.L.; Hamrick, C.; Wood, G. The effect of working serial night shifts on the cognitive functioning of emergency physicians. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2001, 38, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClelland, D.C. How motives, skills, and values determine what people do. Am. Psychol. 1985, 40, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Harter, S. A new self-report scale of intrinsic versus extrinsic orientation in the classroom: Motivational and informational components. Dev. Psychol. 1981, 17, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standage, M.; Gillison, F.; Treasure, D.C. Self-determination and motivation in physical education. In Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Exercise and Sport; Hagger, M.S., Chatzisarantis, N.L.D., Eds.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2007; pp. 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. Intrinsic Motivation; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J. Motivating Others: Nurturing Inner Motivational Resources; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Elliot, A.J. Not all Personal Goals are Personal: Comparing Autonomous and Controlled Reasons for Goals as Predictors of Effort and Attainment. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 24, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolnick, W.S.; Ryan, R.M. Autonomy in children’s learning: An experimental and individual difference investigation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGraw, K.O. The Detrimental Effects of Reward on Performance: A Literature Review and a Prediction Model. In The Hidden Costs of Reward: New Perspectives on the Psychology of Human Motivation London; Lepper, M., Greene, D., Eds.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1978; pp. 33–60. [Google Scholar]

- Chantal, Y.; Guay, F.; Dobreva-Martinova, T.; Vallerand, R.J. Motivation and elite performance: An exploratory investigation with Bulgarian athletes. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 1996, 27, 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Konheim-Kalkstein, Y.L.; Broek, P.V.D. The Effect of Incentives on Cognitive Processing of Text. Discourse Process. 2008, 45, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, C.M.; Diefendorff, J.M.; Kim, T.-Y.; Liu, Z.-Q. A profile approach to self-determination theory motivations at work. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 81, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J.; Davis, C.R.; Townley, J. Perfectionism and workaholism in employees: The role of work motivation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2013, 55, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beek, I.; Taris, T.W.; Schaufeli, W.B. Workaholic and work engaged employees: Dead ringers or worlds apart? J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusurkar, R.A. Autonomous motivation in medical education. Med. Teach. 2018, 41, 1083–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Zhou, M.; Lens, W.; Soenens, B. Experiences of Autonomy and Control among Chinese Learners: Vitalizing or Immobilizing? J. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 97, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyssen, A.; Hansez, I.; Baele, P.; Lamy, M.; De Keyser, V. Occupational stress and burnout in anaesthesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 2003, 90, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Pelletier, L.G.; Blais, M.R.; Briere, N.M.; Senecal, C.; Vallieres, E.F. The Academic Motivation Scale: A Measure of Intrinsic, Extrinsic, and Amotivation in Education. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1992, 52, 1003–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1st & 2nd year | 3rd year | 4th & 5th year | Attending | Consultant | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 17 | 15 | 17 | 12 | 10 |

| Situational Motivation | 1st and 2nd Year | 3rd Year | 4th and 5th Year | Attending | Consultant | ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F (df) | p | η2 | ||||||

| Intrinsic Identified Introjected Extrinsic Amotivation | 5.69 (1.23) 5.51 (1.20) 3.60 (1.28) 2.47 (1.56) 2.11 (1.32) | 5.87 (0.68) 5.38 (0.88) 3.30 (0.94) A 1.82 (0.93) 1.83 (0.84) | 5.99 (0.77) 5.29 (1.08) 2.80 (1.40) A 1.75 (0.78) 1.57 (0.72) | 5.70 (0.92) 4.81 (1.10) 3.38 (1.04) 1.78 (0.75) 2.00 (0.78) | 6.02 (0.44) 5.78 (0.71) 4.69 (0.80) A 1.89 (0.82) 1.58 (0.51) | 0.41(4) 1.31 (4) 4.11 (4) 0.26 (4) 1.01 (4) | 0.799 0.277 0.005 ** 0.264 0.407 | 0.3 0.07 0.20 0.08 0.06 |

| Motivation indices | ||||||||

| Autonomous Controlled | 5.60 (1.16) 3.03 (1.10) | 5.63 (0.72) 2.55 (0.68) | 5.63 (0.79) 2.26 (0.96) | 5.26 (0.95) 2.57 (0.63) | 5.90 (0.55) 3.29 (0.64) B | 0.71 (4) 2.89 (4) | 0.586 0.029 * | 0.04 0.15 |

| Job satisfaction | 5.64 (1.00) | 4.91 (0.79) | 5.29 (0.77) | 4.83 (1.64) | 5.78 (0.44) | 1.95 (4) | 0.112 | 0.12 |

| Situational Motivation | 2. | 3 | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.694 ** | 0.154 | −0.323 ** | −0.637 ** | −0.79 | 0.903 ** | 0.360 ** |

| 0.313 ** | 0.24 | −0.354 ** | 0.23 | 0.936 ** | 0.21 | |

| 0.239 * | 0.118 | 0.826 ** | 0.262 * | 0.28 | ||

| 0.401 * | 0.745 ** | −0.144 | −0.218 | |||

| 0.309 ** | −0.523 ** | −0.265 * | ||||

Motivation indices

| |||||||

| 0.099 | −0.110 | ||||||

| 0.299 * | ||||||

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moll-Khosrawi, P.; Zimmermann, S.; Zoellner, C.; Schulte-Uentrop, L. Understanding Why All Types of Motivation Are Necessary in Advanced Anaesthesiology Training Levels and How They Influence Job Satisfaction: Translation of the Self-Determination Theory to Healthcare. Healthcare 2021, 9, 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9030262

Moll-Khosrawi P, Zimmermann S, Zoellner C, Schulte-Uentrop L. Understanding Why All Types of Motivation Are Necessary in Advanced Anaesthesiology Training Levels and How They Influence Job Satisfaction: Translation of the Self-Determination Theory to Healthcare. Healthcare. 2021; 9(3):262. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9030262

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoll-Khosrawi, Parisa, Stefan Zimmermann, Christian Zoellner, and Leonie Schulte-Uentrop. 2021. "Understanding Why All Types of Motivation Are Necessary in Advanced Anaesthesiology Training Levels and How They Influence Job Satisfaction: Translation of the Self-Determination Theory to Healthcare" Healthcare 9, no. 3: 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9030262

APA StyleMoll-Khosrawi, P., Zimmermann, S., Zoellner, C., & Schulte-Uentrop, L. (2021). Understanding Why All Types of Motivation Are Necessary in Advanced Anaesthesiology Training Levels and How They Influence Job Satisfaction: Translation of the Self-Determination Theory to Healthcare. Healthcare, 9(3), 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9030262