Differences in Function and Healthcare Cost of Older Adults with Dementia by Long-Term Care Service Type: A National Dataset Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

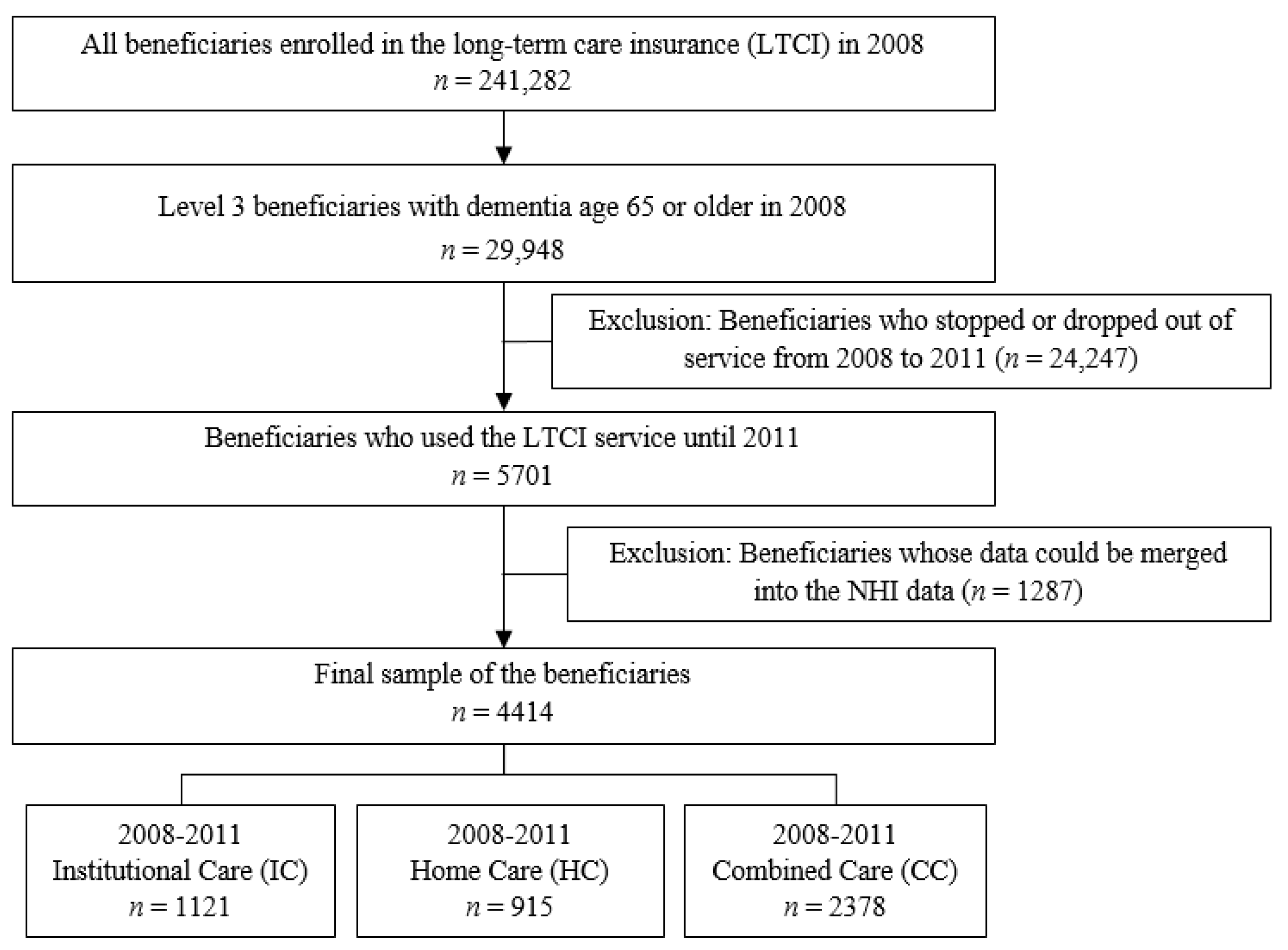

2.2. Study Sample

2.3. Study Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Deterioration, Maintenance, and Improvement of ADL and Cognitive Function

3.3. ADL, Cognitive Function, Medical Cost, and Benefit-Cost in LTCI Beneficiaries Based on Service Type and Time

3.4. Factors Influencing the 4-Year Changes in LTCI Beneficiaries

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 11 October 2020).

- Kumar, A.; Sidhu, J.; Goyal, A.; Tsao, J.W. Alzheimer Disease; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.-Y. “Dementia-friendly communities” and being dementia friendly in healthcare settings. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2017, 30, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heward, M.; Innes, A.; Cutler, C.; Hambidge, S. Dementia-friendly communities: Challenges and strategies for achieving stakeholder involvement. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 858–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.; Kang, M.; Nam, H.; Kim, Y.; Lee, O.; Kim, K. Korean Dementia Observatory 2019; Central Dementia Center: Seoul, Korea, 2020; Available online: https://www.nid.or.kr/info/dataroom_view.aspx?bid=209 (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Kim, H.; Kwon, S. A decade of public long-term care insurance in South Korea: Policy lessons for aging countries. Health Policy 2021, 125, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.W.; Yim, E.S.; Choi, H.S.; Chung, J. Day care vs home care: Effects on functional health outcomes among long-term care beneficiaries with dementia in Korea. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 34, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, T.W.; Yim, E.; Cho, E.; Chung, J. Cognitive function, behavioral problems, and physical function in long-term care insurance beneficiaries with dementia in South Korea: Comparison of home care and institutional care services. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 1467–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korean National Health Insurance Services. Long-Term Care Insurance. Available online: http://www.longtermcare.or.kr/npbs/e/e/100/htmlView?pgmId=npee201m01s&desc=Introduction (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP). Long-Term Care for Older Persons in the Republic of Korea: Development, Challenges and Recommendations: SDD SPPS Project Working Papers Series. 2015. Available online: https://www.unescap.org/resources/long-term-care-older-persons-republic-korea (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Toot, S.; Swinson, T.; Devine, M.; Challis, D.; Orrell, M. Causes of nursing home placement for older people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2017, 29, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brodaty, H.; Donkin, M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 11, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirono, N.; Tsukamoto, N.; Inoue, M.; Moriwaki, Y.; Mori, E. Predictors of long-term institutionalization in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: Role of caregiver burden. No To Shinkei 2002, 54, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prince, M.J.; Prina, M.; Guerchet, M. World Alzheimer Report 2013: Journey of Caring: An Analysis of Long-Term Care for Dementia; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, I.-O.; Park, C.Y.; Lee, Y. Role of healthcare in Korean long-term care insurance. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2012, 27, S41–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shin, J. Long-Term Care Insurance and Health Care Financing of the Korean National Health Insurance Program. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 2014, 34, 68–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sado, M.; Ninomiya, A.; Shikimoto, R.; Ikeda, B.; Baba, T.; Yoshimura, K.; Mimura, M. The estimated cost of dementia in Japan, the most aged society in the world. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e206508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalowsky, B.; Kaczynski, A.; Hoffmann, W. The economic and social burden of dementia diseases in Germany-A meta-analysis. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2019, 62, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, T.W.; Cho, E.; Yim, E.S.; Lee, H.S.; Ko, Y.K.; Kim, B.N.; Kim, S. Activities of daily living in nursing home and home care settings: A retrospective 1-year cohort study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.E. Social Support and Health-Related Quality of Life Among Elderly Individuals Living Alone in South Korea: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Nurs. Res. 2018, 26, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrayo, E.A.; Salmon, J.R.; Polivka, L.; Dunlop, B.D. Utilization across the continuum of long-term care services. Gerontologist 2002, 42, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ettema, T.P.; Dröes, R.M.; De Lange, J.; Ooms, M.E.; Mellenbergh, G.J.; Ribbe, M.W. The concept of quality of life in dementia in the different stages of the disease. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2005, 17, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Karlsson, S.; Edberg, A.-K.; Hallberg, I.R. Professional’s and older person’s assessments of functional ability, health complaints and received care and service: A descriptive study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drachman, D.A.; Swearer, J.M.; O’Donnell, B.F.; Mitchell, A.L.; Maloon, A. The Caretaker Obstreperous-Behavior Rating Assessment (COBRA) Scale. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1992, 40, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, R.L.; Chen, Q.; Finch, M.; Blewett, L.; Burns, R.; Moskowitz, M. The optimal outcomes of post-hospital care under medicare. Health Serv. Res. 2000, 35, 615–661. [Google Scholar]

- Jasiukaitienė, V.; Lukšienė, D.; Tamošiūnas, A.; Radišauskas, R.; Bobak, M. The impact of metabolic syndrome and lifestyle habits on the risk of the first event of cardiovascular disease: Results from a cohort study in lithuanian urban population. Medicina 2020, 56, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chaudhury, H.; Hung, L.; Badger, M. The role of physical environment in supporting person-centered dining in long-term care: A review of the literature. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Dement. 2013, 28, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, D.; Buckwalter, K. Taking Another Look: Thoughts on Behavioral Symptoms in Dementia and Their Measurement. Healthcare 2018, 6, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kane, R.L.; Chen, Q.; Blewett, L.A.; Sangl, J. Do rehabilitative nursing homes improve the outcomes of care? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1996, 44, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruchno, R.A.; Rose, M.S. The effect of long-term care environments on health outcomes. Gerontologist 2000, 40, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schwarzkopf, L.; Menn, P.; Leidl, R.; Graessel, E.; Holle, R. Are community-living and institutionalized dementia patients cared for differently? Evidence on service utilization and costs of care from German insurance claims data. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Liu, E. Influencing Factors of Undermet Care Needs of the Chinese Disabled Oldest Old People When Their Children Are Both Caregivers and Older People: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2020, 8, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Total | Institutional Care | Home Care | Combined Care | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 4414 | 1121 | 915 | 2378 | − | |

| Sex n (%) | Female, | 3735 (84.6) | 971 (86.6) | 733 (80.1) | 2031 (85.4) | <0.001 |

| Male | 679 (15.4) | 150 (13.4) | 182 (19.9) | 347 (14.6) | ||

| Age | mean ± SD | 79.6 ± 6.9 | 80.4 ± 7.1 | 78.9 ± 6.9 | 79.4 ± 6.7 | <0.001 |

| 65–74, n (%) | 1116 (25.3) | 251 (22.4) | 254 (27.8) | 611 (25.7) | <0.001 | |

| 75–84, n (%) | 2125 (48.1) | 524 (46.7) | 441 (48.2) | 1160 (48.8) | ||

| ≥85, n (%) | 1173 (26.6) | 346 (30.9) | 220 (24.0) | 607 (25.5) | ||

| Insurance type n (%) | Medical Aid | 1352 (30.6) | 671 (59.9) | 216 (23.6) | 465 (19.6) | <0.001 |

| NHI | 3062 (69.4) | 450 (40.1) | 699 (76.4) | 1913 (80.4) | ||

| Alone, n (%) | 427 (9.7) | 76 (6.8) | 103 (11.3) | 248 (10.4) | <0.001 | |

| Primary caregiver, n (%) | None | 154 (3.5) | 3 (0.3) | 49 (5.4) | 102 (4.3) | <0.001 |

| Spouse | 604 (13.7) | 1 (0.1) | 247 (27.0) | 356 (15.0) | ||

| Children | 1860 (42.1) | 30 (2.7) | 502 (54.9) | 1328 (55.8) | ||

| Formal | 1796 (40.7) | 1087 (97.0) | 117 (12.8) | 592 (24.9) | ||

| ADL score (mean ± SD) | 21.3 ± 3.2 | 22.1 ± 3.6 | 21.3 ± 3.1 | 20.8 ± 3.0 | <0.001 | |

| Cognitive function score (mean ± SD) | 6.6 ± 2.0 | 6.8 ± 2.0 | 6.1 ± 2.0 | 6.4 ± 1.9 | <0.001 | |

| Medical cost (USD) mean ± SD | 2452 ± 3322 | 2362 ± 2405 | 2913 ± 3351 | 2997 ± 3991 | <0.001 | |

| Benefit-cost (USD) mean ± SD | 2989 ± 2382 | 5565 ± 1234 | 2208 ± 1160 | 2076 ± 1814 | <0.001 | |

| Variable | Total | Institutional Care | Home Care | Combined Care | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADL | 2008 to 2009 | |||||

| Deteriorated | 2618 (59.3) | 686 (61.2) | 480 (52.5) | 1452 (61.1) | <0.001 | |

| Maintained | 700 (15.9) | 162 (14.5) | 166 (18.1) | 372 (15.2) | ||

| Improved | 1096 (24.8) | 273 (24.4) | 269 (29.4) | 554 (23.3) | ||

| 2008 to 2010 | ||||||

| Deteriorated | 3100 (70.2) | 835 (74.5) | 570 (62.3) | 1695 (71.3) | <0.001 | |

| Maintained | 399 (9.0) | 81 (7.2) | 91 (9.9) | 227 (9.5) | ||

| Improved | 915 (20.7) | 205 (18.3) | 254 (27.8) | 456 (19.2) | ||

| 2008 to 2011 | ||||||

| Deteriorated | 3449 (78.1) | 881 (78.6) | 650 (71.0) | 1918 (80.7) | <0.001 | |

| Maintained | 249 (5.6) | 52 (4.6) | 68 (7.4) | 129 (5.4) | ||

| Improved | 716 (16.2) | 188 (16.8) | 197 (21.5) | 331 (13.9) | ||

| Cognitive function | 2008 to 2009 | |||||

| Deteriorated | 1700 (38.5) | 399 (35.6) | 323 (35.3) | 978 (41.1) | <0.001 | |

| Maintained | 1210 (27.4) | 303 (27.0) | 260 (28.4) | 647 (27.2) | ||

| Improved | 1504 (34.1) | 419 (37.4) | 332 (36.3) | 753 (31.7) | ||

| 2008 to 2010 | ||||||

| Deteriorated | 2079 (47.1) | 486 (43.4) | 406 (44.4) | 1187 (49.9) | <0.001 | |

| Maintained | 944 (21.4) | 246 (21.9) | 200 (21.9) | 498 (20.9) | ||

| Improved | 1391 (31.5) | 389 (34.7) | 309 (33.8) | 693 (29.1) | ||

| 2008 to 2011 | ||||||

| Deteriorated | 2319 (52.5) | 510 (45.5) | 464 (50.7) | 1345 (56.6) | <0.001 | |

| Maintained | 839 (19.0) | 252 (22.5) | 173 (18.9) | 414 (17.4) | ||

| Improved | 1256 (28.5) | 359 (32.0) | 278 (30.4) | 619 (26.0) | ||

| Variable | Service Type (Mean ± SD) | F (p-Value) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional Care | Home Care | Combined Care | Service Type | Time | Time by Service Type | ||

| ADL | 2008 | 22.2 ± 3.6 | 21.4 ± 3.2 | 20.9 ± 3.0 | 78.45 (<0.001) | 1519.61 (<0.001) | 21.95 (<0.001) |

| 2009 | 24.8 ± 5.2 | 22.8 ± 4.5 | 23.3 ± 4.8 | ||||

| 2010 | 27.1 ± 5.9 | 24.0 ± 5.5 | 25.2 ± 5.7 | ||||

| 2011 | 28.6 ± 6.6 | 26.3 ± 6.7 | 27.7 ± 6.5 | ||||

| Cognitive function | 2008 | 6.8 ± 2.0 | 6.2 ± 2.1 | 6.5 ± 1.9 | 40.48) (<0.001) | 259.63 (<0.001) | 16.58 (<0.001) |

| 2009 | 6.8 ± 2.0 | 6.1 ± 2.1 | 6.7 ± 2.1 | ||||

| 2010 | 7.0 ± 2.1 | 6.4 ± 2.1 | 7.0 ± 2.0 | ||||

| 2011 | 7.2 ± 2.1 | 6.7 ± 2.2 | 7.3 ± 2.1 | ||||

| Medical cost (USD) | 2008 | 2362 ± 2405 | 2913 ± 3351 | 2997 ± 3991 | 26.78 (<0.001) | 14.77 (<0.001) | 6.43 (<0.001) |

| 2009 | 2213 ± 2397 | 2772 ± 3443 | 2759 ± 3628 | ||||

| 2010 | 2148 ± 2322 | 2852 ± 3783 | 2640 ± 3419 | ||||

| 2011 | 2478 ± 3328 | 3651 ± 5494 | 2781 ± 3989 | ||||

| Benefit-cost (USD) | 2008 | 5565 ± 1234 | 2208 ± 1160 | 2076 ± 1814 | 2125.38 (<0.001) | 11,878.17 (<0.001) | 517.41 (<0.001) |

| 2009 | 12,414 ± 2044 | 7190 ± 1943 | 8192 ± 3271 | ||||

| 2010 | 13,486 ± 1900 | 7962 ± 1883 | 11,481 ± 3161 | ||||

| 2011 | 13,302 ± 2570 | 7703 ± 2263 | 12,683 ± 2990 | ||||

| 4-Year Changes (2011–2008) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADL | Cognitive Function | Medical Cost | Benefit-Cost | ||||||

| Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | ||

| Intercept | 11.864 | <0.001 | 3.22 | <0.001 | −579.70 | 0.605 | 5052.87 | <0.001 | |

| LTC type (ref. home care) | Institutional care | 3.29 (0.21) | <0.001 | 0.49 (0.09) | <0.001 | 1269.78 (0.11) | <0.001 | 2940.39 (0.35) | <0.001 |

| Combined care | 1.87 (0.14) | <0.001 | 0.50 (0.11) | <0.001 | −648.57 (−0.06) | 0.001 | 5198.26 (0.70) | <0.001 | |

| Sex (ref. male) | Female | 0.98 (0.05) | <0.001 | 0.33 (0.05) | <0.001 | −399.68 (−0.03) | 0.069 | 182.96 (0.02) | 0.173 |

| Age | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.388 | 0.02 (0.05) | <0.001 | 28.97 (0.04) | 0.010 | −14.30 (−0.03) | 0.036 | |

| Insurance type (ref. NHI) | Medical Aid | 0.20 (0.01) | 0.583 | 0.19 (0.04) | 0.087 | −691.62 (−0.06) | 0.015 | 240.27 (0.03) | 0.165 |

| Caregiver (ref. formal caregiver) | None | 0.75 (0.02) | 0.188 | 0.13 (0.01) | 0.477 | 1794.17 (0.07) | <0.001 | 989.37 (0.05) | <0.001 |

| Spouse | 2.74 (0.14) | <0.001 | 0.39 (0.06) | 0.001 | 2887.29 (0.20) | <0.001 | 871.24 (0.08) | <0.001 | |

| Children | 1.21 (0.09) | <0.001 | 0.10 (0.02) | 0.271 | 2281.76 (0.22) | <0.001 | 683.98 (0.09) | <0.001 | |

| ADL score at baseline | −0.61 (−0.29) | <0.001 | −0.06 (−0.08) | <0.001 | −107.05 (−0.07) | <0.001 | 3.30 (0.01) | 0.659 | |

| Cognitive function score at baseline | 0.27 (0.08) | <0.001 | −0.60 (−0.52) | <0.001 | 54.17 (0.02) | 0.153 | 44.74 (0.02) | 0.054 | |

| Adj R2 | 0.112 | 0.280 | 0.041 | 0.325 | |||||

| F (P) | 51.76 (<0.001) | 156.76 (<0.001) | 18.24 (<0.001) | 194.10 (<0.001) | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, I.; Lee, K.; Yim, E.; Noh, K. Differences in Function and Healthcare Cost of Older Adults with Dementia by Long-Term Care Service Type: A National Dataset Analysis. Healthcare 2021, 9, 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9030307

Park I, Lee K, Yim E, Noh K. Differences in Function and Healthcare Cost of Older Adults with Dementia by Long-Term Care Service Type: A National Dataset Analysis. Healthcare. 2021; 9(3):307. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9030307

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Ilsu, Kyounga Lee, Eunshil Yim, and Kyunghee Noh. 2021. "Differences in Function and Healthcare Cost of Older Adults with Dementia by Long-Term Care Service Type: A National Dataset Analysis" Healthcare 9, no. 3: 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9030307