Determinants Impacting User Behavior towards Emergency Use Intentions of m-Health Services in Taiwan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. m-Health in Taiwan

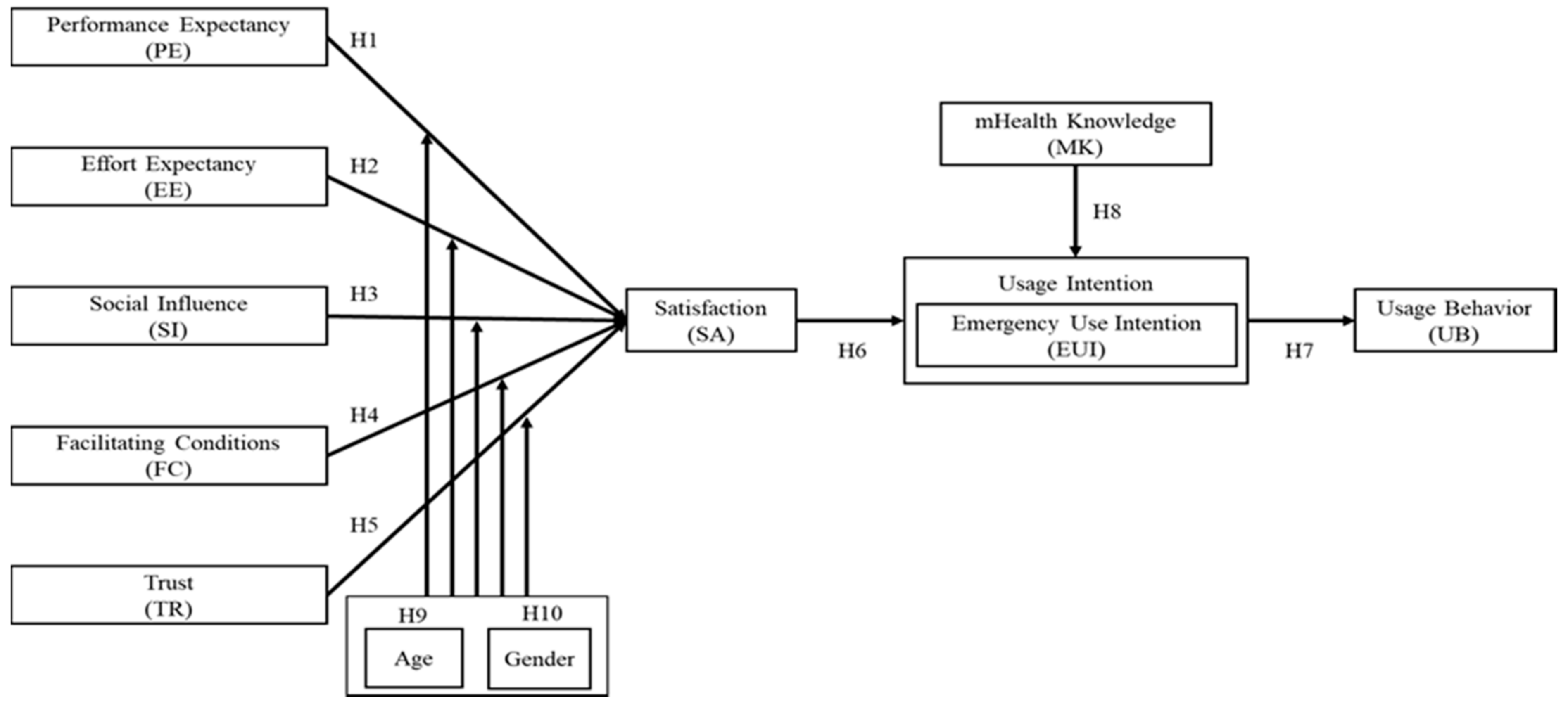

2.2. Hypotheses Development

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Survey Instrument

3.2. Sampling Design and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analytic Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Structural Model and Hypotheses Testing

4.3. Moderation Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Implications

7. Conclusions

Limitations and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

- Appointment Service

- Mask Map

- eMask

- NHI Express APP

- PharmaCloud System

- Fitness App

- Health Management App

- Monitor App

- Personal Health Record

- Emergency Wound Knowledge

| Experience | |

| Yes/No |

| Yes/No |

| Yes/No |

| Yes/No |

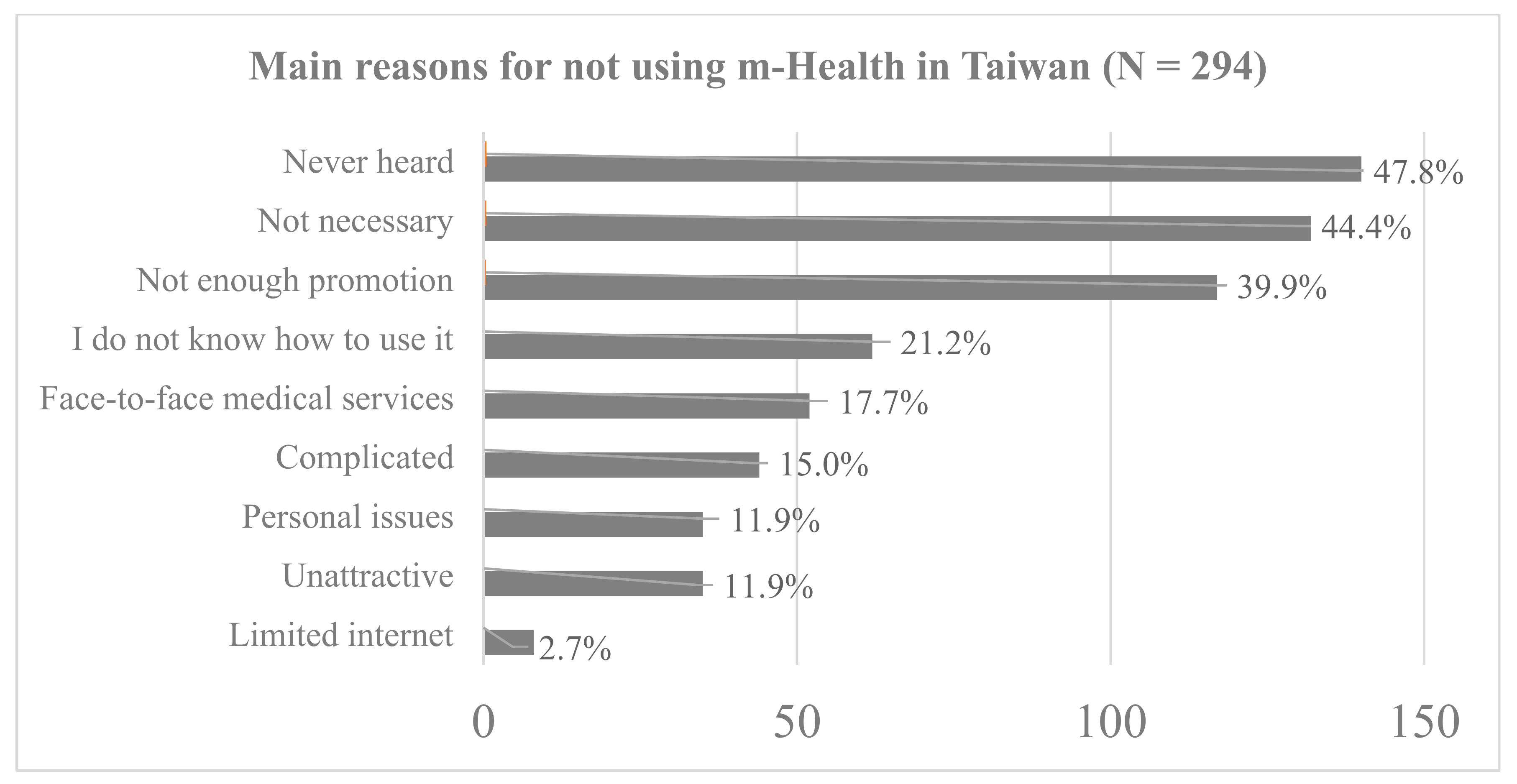

| 4-1 Which option is the reason why you have not used an "m-Health Mobile Medical" service or application? (more than one option) □Limited internet service on my phone □There is not necessary □Never heard about it □I do not know how to use it □Not enough promotion □It is too complicated □I prefer face-to-face medical services □Unattractive □Personal issues □Other reason | |

□PharmaCloud System □Fitness App □Health Management App □Monitor App □Personal Health Record □Emergency Wound Knowledge □Other | |

| |

| Performance Expectancy |

|

| Effort expectancy |

|

| Social influence |

|

| Facilitating conditions |

|

| Trust |

|

| Satisfaction |

|

| Emergency use intention |

|

| Usage behavior |

|

| m-Health Knowledge |

|

| Demographics |

| 1. Gender: 口male 口 female |

| 2. Age: 口20(include)-30 口31~40 口41~50 口51~65口more than 65 |

| 4. Education: 口Below junior high school(include) 口Senior high school (include vocational) 口University 口Above of Master |

| 5. Income: 口NT$10,000 or less 口NT$10,001~30,000 口NT$30,001~50,000口NT$50,001~70,000 口NT$70,001 or more |

| 6. In the past, have you been asked to complete home isolation or quarantine? 口yes 口no |

| 7. Where have you been quarantined in the past? 口Home口Epidemic Prevention Hotel |

| 8. During quarantine, which medical service did you prioritize for any medical requirements? 口m-Health services or apps 口Face to face service 口Emergency call 11 |

References

- Wang, C.J.; Ng, C.Y.; Brook, R.H. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: Big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing. JAMA 2020, 323, 1341–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronavirus Press Release. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Bulletin/Detail/JrlVKIn-427XAfDELEuDEg?typeid=158 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Radzi, C.W.J.B.W.M.; Jenatabadi, H.S.; Samsudin, N. mHealth Apps Assessment among Postpartum Women with Obesity and Depression. Health 2020, 8, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buntin, M.B.; Burke, M.F.; Hoaglin, M.C.; Blumenthal, D. The Benefits of Health Information Technology: A Review of The Recent Literature Shows Predominantly Positive Results. Health Aff. 2011, 30, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, T.G.; Effros, R.M.; Palar, K.; Keeler, E.B. Waste in the U.S. Health Care System: A Conceptual Framework. Milbank Q. 2008, 86, 629–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, I.-L.; Li, J.-Y.; Fu, C.-Y. The adoption of mobile healthcare by hospital’s professionals: An integrative perspective. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 51, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giansanti, D. The Role of the mHealth in the Fight against the Covid-19: Successes and Failures. Healthcare 2021, 9, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobair, K.M.; Sanzogni, L.; Sandhu, K. Expectations of telemedicine health service adoption in rural Bangladesh. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 238, 112485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijsanayotin, B.; Pannarunothai, S.; Speedie, S.M. Factors influencing health information technology adoption in Thailand’s community health centers: Applying the UTAUT model. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2009, 78, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, C.-H.; Tang, K.-Y. Examining a Model of Mobile Healthcare Technology Acceptance by the Elderly in Taiwan. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2015, 18, 292–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, W.-M.; Lee, P.K.C.; Lu, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Yu, Q. What Motivates Chinese Young Adults to Use mHealth? Healthcare 2019, 7, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, X.; Hsieh, J.J.P.-A.; Rai, A. Motivational Differences Across Post-Acceptance Information System Usage Behaviors: An Investigation in the Business Intelligence Systems Context. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 659–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, F.; Ngai, E.; Ju, X. Understanding mobile health service use: An investigation of routine and emergency use intentions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 45, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saga, V.L.; Zmud, R.W. The Nature and Determinants of IT Acceptance, Routinization, and Infusion. In Proceedings of the IFIP TC8 Working Conference on Diffusion, Transfer and Implementation of Information Technology, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 11–13 October 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram, S.; Schwarz, A.; Jones, E.; Chin, W.W. Technology use on the front line: How information technology enhances individual performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2007, 35, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G. Davis User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Digital Nation & Innovative Economic Development Program (DIGI+) 2017–2025. Available online: https://digi.ey.gov.tw/File/79CC5E9ECE14A97E (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Yang, Z.-L. Opportunities for The Transformation of ICT Industry as Driven by the Convergence of Worldwide Emerging Services: Current Status and Challenges of Digital Convergence; Market Intelligence & Consulting Institute: Taipei, Taiwan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- M-Taiwan Plan. Available online: http://dig.taichung.gov.tw/TcBBeam/people/aboutM.aspx (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- The Mask-Rationing Plan 2.0 Press Release. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov.tw/Bulletin/Detail/l93JyhKzaG5hHmhcIs5_HQ?typeid=9 (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Loo, W.; Yeow, P.H.; Chong, S. Acceptability of Multipurpose Smart National Identity Card: An Empirical Study. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2011, 14, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Zhang, X. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology: U.S. Vs. China. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2010, 13, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Ray, P.; D’Ambra, J. Continuance of mHealth services at the bottom of the pyramid: The roles of service quality and trust. Electron. Mark. 2013, 23, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding Information Systems Continuance: An Expectation-Confirmation Model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, F.; Hong Kong University of Science and Technology; Thong, J.; Venkatesh, V.; Brown, S.; Hu, P.; Tam, K. University of Arkansas; University of Arizona; University of Utah Modeling Citizen Satisfaction with Mandatory Adoption of an E-Government Technology. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2010, 11, 519–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, R.J.; Brown, R.L.; Scanlon, M.C.; Karsh, B.-T. Pharmacy workers’ perceptions and acceptance of bar-coded medication technology in a pediatric hospital. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2012, 8, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rahman, M.S.; Hanifi, S.; Khatun, F.; Iqbal, M.; Rasheed, S.; Ahmed, T.; Hoque, S.; Sharmin, T.; Khan, N.-U.Z.; Mahmood, S.S.; et al. Knowledge, attitudes and intention regarding mHealth in generation Y: Evidence from a population based cross sectional study in Chakaria, Bangladesh. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deng, L.; Turner, D.E.; Gehling, R.; Prince, B. User experience, satisfaction, and continual usage intention of IT. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2010, 19, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.-C.; Chiou, J.-S. The impact of perceived ease of use on Internet service adoption: The moderating effects of temporal distance and perceived risk. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.-H.; Chang, J.-J.; Tang, K.-Y. Exploring the influential factors in continuance usage of mobile social Apps: Satisfaction, habit, and customer value perspectives. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Giffin, K. The contribution of studies of source credibility to a theory of interpersonal trust in the communication process. Psychol. Bull. 1967, 68, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y. The privacy–personalization paradox in mHealth services acceptance of different age groups. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2016, 16, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Benbasat, I.; Pavlou, P. A Research Agenda for Trust in Online Environments. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2008, 24, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, I.O.; Pateli, A.G.; Giannakos, M.N.; Chrissikopoulos, V. Moderating effects of online shopping experience on customer satisfaction and repurchase intentions. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2014, 42, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, J.-S. The antecedents of consumers’ loyalty toward Internet Service Providers. Inf. Manag. 2004, 41, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L. Marketing Management, 15th ed.; Pearson: England, UK, 2016; p. 153. [Google Scholar]

- Au, N.; Ngai, E.W.T.; Cheng, T.C.E. Extending the Understanding of End User Information Systems Satisfaction Formation: An Equitable Needs Fulfillment Model Approach. MIS Q. 2008, 32, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, S.K.; Sharma, M. Examining the role of trust and quality dimensions in the actual usage of mobile banking services: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagger, T.S.; Sweeney, J.C.; Johnson, L.W. A hierarchical model of health service quality: Scale development and inves-tigation of an integrated model. J Serv Res 2007, 10, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Säilä, T.; Mattila, E.; Kaila, M.; Aalto, P.; Kaunonen, M. Measuring patient assessments of the quality of outpatient care: A systematic review. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2008, 14, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barutçu, S.; Barutçu, E.; Ünal Adıgüzel, D. A technology acceptance analysis for mhealth apps: The case of Turkey. BNEJSS. 2018, 4, 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.-S. Factors affecting individuals to adopt mobile banking: Empirical evidence from the UTAUT model. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2012, 13, 104–121. [Google Scholar]

- Mafé, C.R.; Blas, S.S.; Tavera-Mesías, J.F. A comparative study of mobile messaging services acceptance to participate in television programmes. J. Serv. Manag. 2010, 21, 69–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P. Assessing IT Usage: The Role of Prior Experience. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turner, M.; Kitchenham, B.; Brereton, P.; Charters, S.; Budgen, D. Does the technology acceptance model predict actual use? A systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2010, 52, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, D. Understanding Customer Role and its Importance in the Formation of Service Quality Expectations. Serv. Ind. J. 2000, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.; Rajan, P. Modeling intermediary satisfaction with mandatory adoption of e-government technologies for food distribution. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2016, 12, 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.; Mirusmonov, M.; Lee, I. An empirical examination of factors influencing the intention to use mobile payment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, X.; Lai, K.-H.; Guo, F.; Li, C. Understanding Gender Differences in m-Health Adoption: A Modified Theory of Reasoned Action Model. Telemed. e-Health 2014, 20, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.Y. Online Health Information Seeking Behavior in Hong Kong: An Exploratory Study. J. Med. Syst. 2010, 34, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, G.M.; Shin, B.; Lee, H.G. Understanding dynamics between initial trust and usage intentions of mobile banking. Inf. Syst. J. 2009, 19, 283–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, B.; Han, I. Effect of trust on customer acceptance of Internet banking. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2002, 1, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. An Empirical Examination of Initial Trust in Mobile Payment. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2014, 77, 1519–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; D’Ambra, J.; Ray, P. Development and validation of an instrument to measure user perceived service quality of mHealth. Inf. Manag. 2013, 50, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, J.-H.; Wang, Y.-M. Measuring KMS success: A respecification of the DeLone and McLean’s model. Inf. Manag. 2006, 43, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dünnebeil, S.; Sunyaev, A.; Blohm, I.; Leimeister, J.M.; Krcmar, H. Determinants of physicians’ technology acceptance for e-health in ambulatory care. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2012, 81, 746–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Awang, Z. SEM Made Simple: A Gentle Approach to Learning Structural Equation Modeling; MPWS Rich Publication: Bandar Baru Bangi, Malaysia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. Mis. Q. 1998, 22, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, N. Uses and abuses of coefficient alpha. Psychol. Assess. 1996, 8, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, P.Y.K.; Hu, P.J.-H. Information Technology Acceptance by Individual Professionals: A Model Comparison Approach. Decis. Sci. 2001, 32, 699–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, J.H. Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, W.J.; Xia, W.; Torkzadeh, G. A Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the End-User Computing Satisfaction Instrument. MIS Q. 1994, 18, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetana, J.G.; Campione-Barr, N.; Metzger, A. Adolescent Development in Interpersonal and Societal Contexts. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2006, 57, 255–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- The number of mHealth users. Available online: https://www.nhi.gov.tw/Content_List.aspx?n=6749F01C9692626F&topn=5FE8C9FEAE863B46 (accessed on 20 April 2020).

| Constructs | Items | Description | Item Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Expectancy | PE1 | I find m-Health useful in my life during the COVID-19 pandemic. | [16,22]. |

| PE2 | Using m-Health increases my chances of meeting my needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. | ||

| PE3 | Using m-Health helps me in manage my daily healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic. | ||

| PE4 | Using m-Health service increases my capability to manage my health during the COVID-19 pandemic. | ||

| Effort Expectancy | EE1 | Learning how to use m-Health is easy for me. | [16,22]. |

| EE2 | My interaction with m-Health is clear and understandable. | ||

| EE3 | I find m-Health easy to use. | ||

| Social Influence | SI1 | People who are important to me think that I should use m-Health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. | [16,22]. |

| SI2 | People who influence my behavior think that I should use m-Health during the COVID-19 pandemic. | ||

| SI3 | People in my social groups who use m-Health service are seen as more prestigious than those who do not. | ||

| Facilitating Conditions | FC1 | I have the resources necessary to use m-Health services. | [16,22]. |

| FC2 | I have the knowledge necessary to use m-Health services. | ||

| FC3 | I can get help from others when I have difficulties using m-Health services. | ||

| FC4 | m-Health instructions are useful to me when I use m-Health services. | ||

| Trust | TR1 | I trust my m-Health applications during the COVID-19 pandemic. | [52,53,54]. |

| TR2 | I find m-Health reliable in conducting health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. | ||

| TR3 | I feel that m-Health is safe for receiving reliable medical information during the COVID-19 pandemic. | ||

| TR4 | I trust m-Health’s commitment to satisfy my medical information needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. | ||

| Satisfaction | SA1 | I am satisfied with m-Health efficiency. | [55,56]. |

| SA2 | I am satisfied with m-Health service quality. | ||

| SA3 | I am satisfied with the presentation of the m-Health service’s user interface. | ||

| SA4 | I am satisfied with my overall experience using m-Health. | ||

| Emergency use intention | EUI1 | I use m-Health services when I am in urgent need of medical care during the COVID-19 pandemic. | [13,16]. |

| EUI2 | I will consider using m-Health services if I have urgent medical requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic. | ||

| EUI3 | m-Health is the first choice if I need urgent medical health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. | ||

| EUI4 | I will continue to use m-Health services if I need urgent medical care in future. | ||

| Usage Behavior | UB1 | m-Health service is a pleasant experience. | [16,22]. |

| UB2 | I really want to use m-Health services to keep my healthy during the COVID-19 pandemic. | ||

| UB3 | I spend a lot of time using m-Health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. | ||

| UB4 | I use m-Health services on regular basis during the COVID-19 pandemic. | ||

| m-Health Knowledge | MK1 | I have already used or practiced m-Health Apps to make myself familiar with the functionality. | [57]. |

| MK2 | I have already made myself familiar with different versions of m-Health. | ||

| MK3 | I know the types of m-Health Apps that are commonly used. | ||

| MK4 | I can skillfully operate commonly used m-Health Apps. |

| Demographic Characteristics | Have used m-Health (N = 371) 55.8% | Have not used m-Health (N = 294) 44.2% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 173 | 46.6 | 144 | 49.0 |

| Female | 198 | 53.4 | 150 | 51.0 |

| Age | ||||

| 20–30 years | 111 | 29.9 | 111 | 37.8 |

| 31–50 years | 175 | 47.2 | 101 | 34.4 |

| More than 51 years | 85 | 22.9 | 82 | 27.9 |

| Education | ||||

| Below senior high school | 40 | 10.8 | 55 | 18.7 |

| University | 206 | 55.5 | 175 | 59.5 |

| Above of Master | 125 | 33.7 | 64 | 21.8 |

| Profession | ||||

| Employee | 295 | 79.5 | 203 | 69.1 |

| Student | 55 | 14.8 | 60 | 20.4 |

| Home keeper | 21 | 5.7 | 31 | 10.5 |

| About COVID-19 | ||||

| (a) Home quarantine | ||||

| Yes | 11 | 3.0 | 6 | 2.0 |

| No | 360 | 97.0 | 288 | 98.0 |

| (b) Quarantine place | (N = 11) | (N = 6) | ||

| Home | 9 | 5 | ||

| Epidemic Prevention Hotel | 2 | 1 | ||

| (c) Priority medical service | (N = 11) | (N = 6) | ||

| m-Health services or Apps | 6 | 1 | ||

| Face-to-face service | 4 | 3 | ||

| Emergency call 119 | 1 | 2 | ||

| (d) Use of m-Health APP related to COVID-19 in the past three moths | (N = 665) | (N = 665) | ||

| Yes | 371 | 55.8 | ||

| No | 294 | 44.2% | ||

| Factors | Items | Mean | Factor Loadings | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Expectancy | PE1 | 4.13 | 0.689 | 0.881 | 0.651 | 0.877 |

| PE2 | 4.08 | 0.844 | ||||

| PE3 | 4.04 | 0.846 | ||||

| PE4 | 3.98 | 0.837 | ||||

| Effort Expectancy | EE1 | 4.02 | 0.823 | 0.925 | 0.806 | 0.924 |

| EE2 | 3.92 | 0.945 | ||||

| EE3 | 3.95 | 0.920 | ||||

| Social Influence | SI1 | 3.65 | 0.885 | 0.860 | 0.754 | 0.859 |

| SI2 | 3.47 | 0.851 | ||||

| Facilitating Conditions | FC2 | 3.94 | 0.731 | 0.714 | 0.455 | 0.715 |

| FC3 | 3.92 | 0.652 | ||||

| FC4 | 3.91 | 0.636 | ||||

| TR2 | 3.91 | 0.813 | ||||

| Trust | TR3 | 3.97 | 0.845 | 0.870 | 0.690 | 0.869 |

| TR4 | 3.95 | 0.833 | ||||

| Satisfaction | SA1 | 3.90 | 0.867 | 0.919 | 0.740 | 0.915 |

| SA2 | 3.91 | 0.901 | ||||

| SA3 | 3.73 | 0.785 | ||||

| SA4 | 3.91 | 0.883 | ||||

| Emergency use intention | EUI2 | 3.77 | 0.819 | 0.906 | 0.763 | 0.904 |

| EUI3 | 3.56 | 0.893 | ||||

| EUI4 | 3.72 | 0.906 | ||||

| Usage Behavior | UB1 | 3.89 | 0.849 | 0.839 | 0.635 | 0.834 |

| UB2 | 3.78 | 0.779 | ||||

| UB4 | 3.74 | 0.759 | ||||

| m-Health Knowledge | MK2 | 3.32 | 0.794 | 0.887 | 0.725 | 0.886 |

| MK3 | 3.56 | 0.880 | ||||

| MK4 | 3.54 | 0.877 | ||||

| Total | 0.865 |

| Quality-of-Fit Measure | Recommended Value | Measurement Model (CFA) | Structural Model (SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | 583.328 | 884.488 | |

| d.f | 314 | 327 | |

| χ2/d.f | <3.00 | 1.858 | 2.705 |

| p-Value | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| GFI | >0.80 | 0.901 | 0.858 |

| AGFI | >0.80 | 0.872 | 0.824 |

| CFI | >0.90 | 0.966 | 0.930 |

| RMSEA | <0.07 | 0.048 | 0.068 |

| CR | AVE | PE | EE | SI | FC | TR | SA | EU | UB | MK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | 0.881 | 0.650 | 0.806 | ||||||||

| EE | 0.925 | 0.806 | 0.507 ** | 0.897 | |||||||

| SI | 0.860 | 0.754 | 0.461 ** | 0.412 ** | 0.868 | ||||||

| FC | 0.714 | 0.455 | 0.652 ** | 0.580 ** | 0.457 ** | 0.674 | |||||

| TR | 0.877 | 0.642 | 0.652 ** | 0.580 ** | 0.457 ** | 0.635 ** | 0.801 | ||||

| SA | 0.919 | 0.740 | 0.615 ** | 0.657 ** | 0.471 ** | 0.640 ** | 0.688 ** | 0.860 | |||

| EU | 0.906 | 0.764 | 0.528 ** | 0.414 ** | 0.481 ** | 0.469 ** | 0.599 ** | 0.547 ** | 0.874 | ||

| UB | 0.839 | 0.635 | 0.598 ** | 0.536 ** | 0.551 ** | 0.587 ** | 0.660 ** | 0.731 ** | 0.701 ** | 0.797 | |

| MK | 0.887 | 0.725 | 0.447 ** | 0.564 ** | 0.467 ** | 0.582 ** | 0.525 ** | 0.655** | 0.498 ** | 0.672 ** | 0.851 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Standardized Path Coefficient | t-Statistics | Test Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | PE→SA | 0.138 * | 2.076 | Supported |

| H2 | EE→SA | 0.069 | 0.882 | Not Supported |

| H3 | SI→SA | −0.002 | −0.038 | Not Supported |

| H4 | FC→SA | 0.550 *** | 3.939 | Supported |

| H5 | TR→SA | 0.190 * | 2.004 | Supported |

| H6 | SA→EUI | 0.483 *** | 7.350 | Supported |

| H7 | EUI→UB | 0.835 *** | 14.030 | Supported |

| H8 | MK→EUI | 0.260 *** | 4.038 | Supported |

| Hypothesized Paths | (H9) Age | (H10) Gender | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–30 Years Old | 31–50 Years Old | More Than 51 | Support | Male | Female | Support | |

| (N = 111) | (N = 175) | (N = 85) | (N = 173) | (N = 198) | |||

| (a) PE→SA | 0.268 * | 0.219 * | 0.174 * | Partial | 0.146 * | 0.196 * | Partial |

| (b) EE→SA | 0.042 | 0.035 | 0.037 | Not | 0.063 | 0.072 | Not |

| (c) SI→SA | −0.010 | −0.009 | −0.009 | Not | 0.051 | 0.056 | Not |

| (d) FC→SA | 0.523 * | 0.515 * | 0.429 * | Partial | 0.595 * | 0.638 * | Partial |

| (e) TR→SA | 0.236 * | 0.204* | 0.182* | Partial | 0.109 | 0.110 | Not |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, W.-I.; Fu, H.-P.; Mendoza, N.; Liu, T.-Y. Determinants Impacting User Behavior towards Emergency Use Intentions of m-Health Services in Taiwan. Healthcare 2021, 9, 535. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9050535

Lee W-I, Fu H-P, Mendoza N, Liu T-Y. Determinants Impacting User Behavior towards Emergency Use Intentions of m-Health Services in Taiwan. Healthcare. 2021; 9(5):535. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9050535

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Wan-I, Hsin-Pin Fu, Nelio Mendoza, and Tzu-Yu Liu. 2021. "Determinants Impacting User Behavior towards Emergency Use Intentions of m-Health Services in Taiwan" Healthcare 9, no. 5: 535. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9050535

APA StyleLee, W.-I., Fu, H.-P., Mendoza, N., & Liu, T.-Y. (2021). Determinants Impacting User Behavior towards Emergency Use Intentions of m-Health Services in Taiwan. Healthcare, 9(5), 535. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9050535