Pediatricians’ Compliance to the Clinical Management Guidelines for Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Infants and Young Children in Pakistan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population and Sample Size Calculation

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- pediatricians or physicians working in pediatric settings of the hospital, including neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)/neonatal care, pediatric intensive care (PIC), pulmonology, emergency medicine, infectious diseases, outpatient clinics, general pediatrics, and the private pediatric clinics and

- if they agreed to participate in the study. When potential respondents were approached, they were briefed about the objectives of the study and the time required to complete the survey. They were informed that no incentives will be presented to them for their contribution and that participation is voluntary.

2.4. Study Instrument

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Respondents’ Preferences for Antibiotic Treatment in a CAP Child

3.3. Respondents’ Practice for the Duration of CAP Hospitalization and IV Antibiotic Use

3.4. Respondents’ Perceived Indications for CAP Hospitalization, Antibiotic Therapy, and ICU Admission

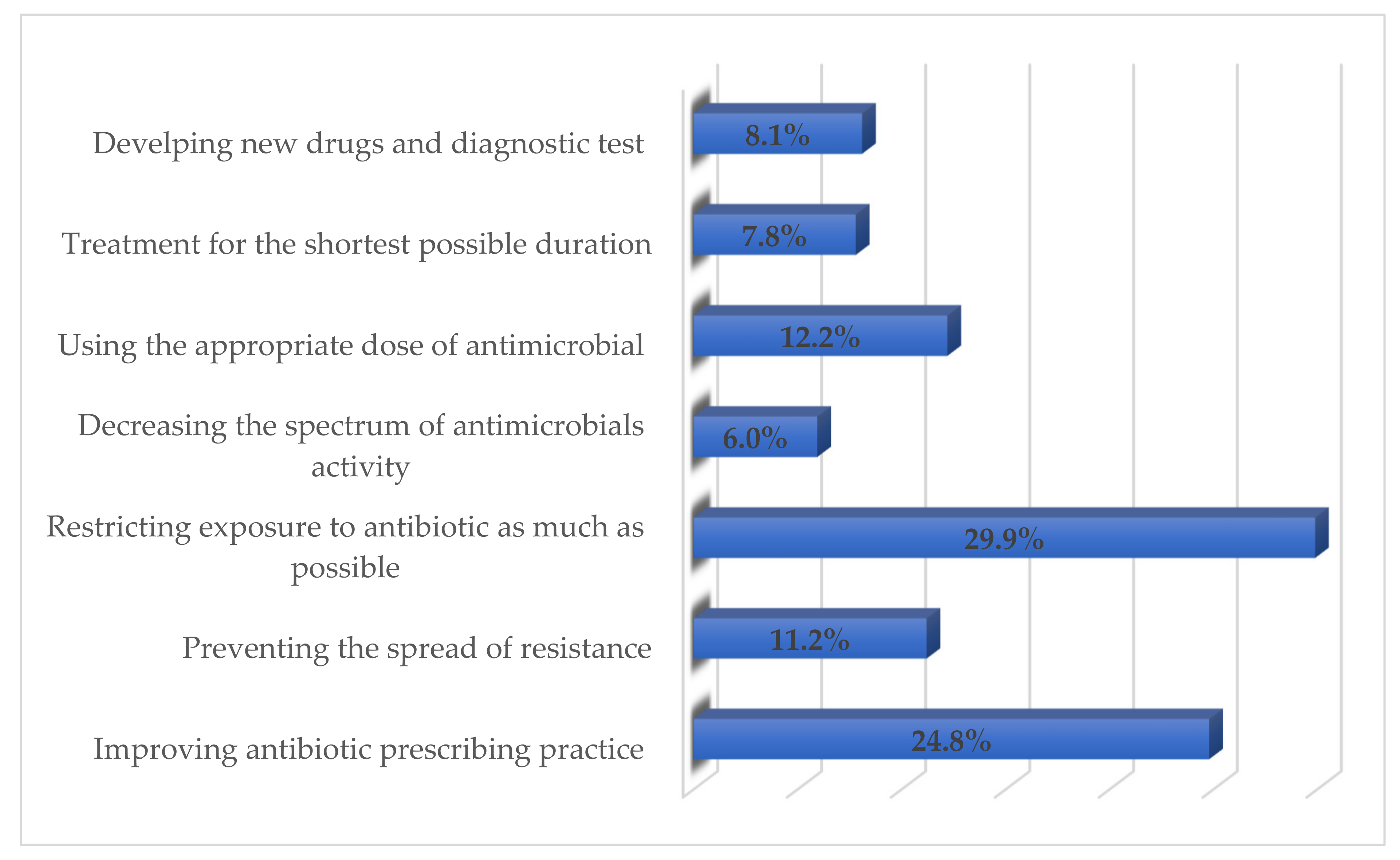

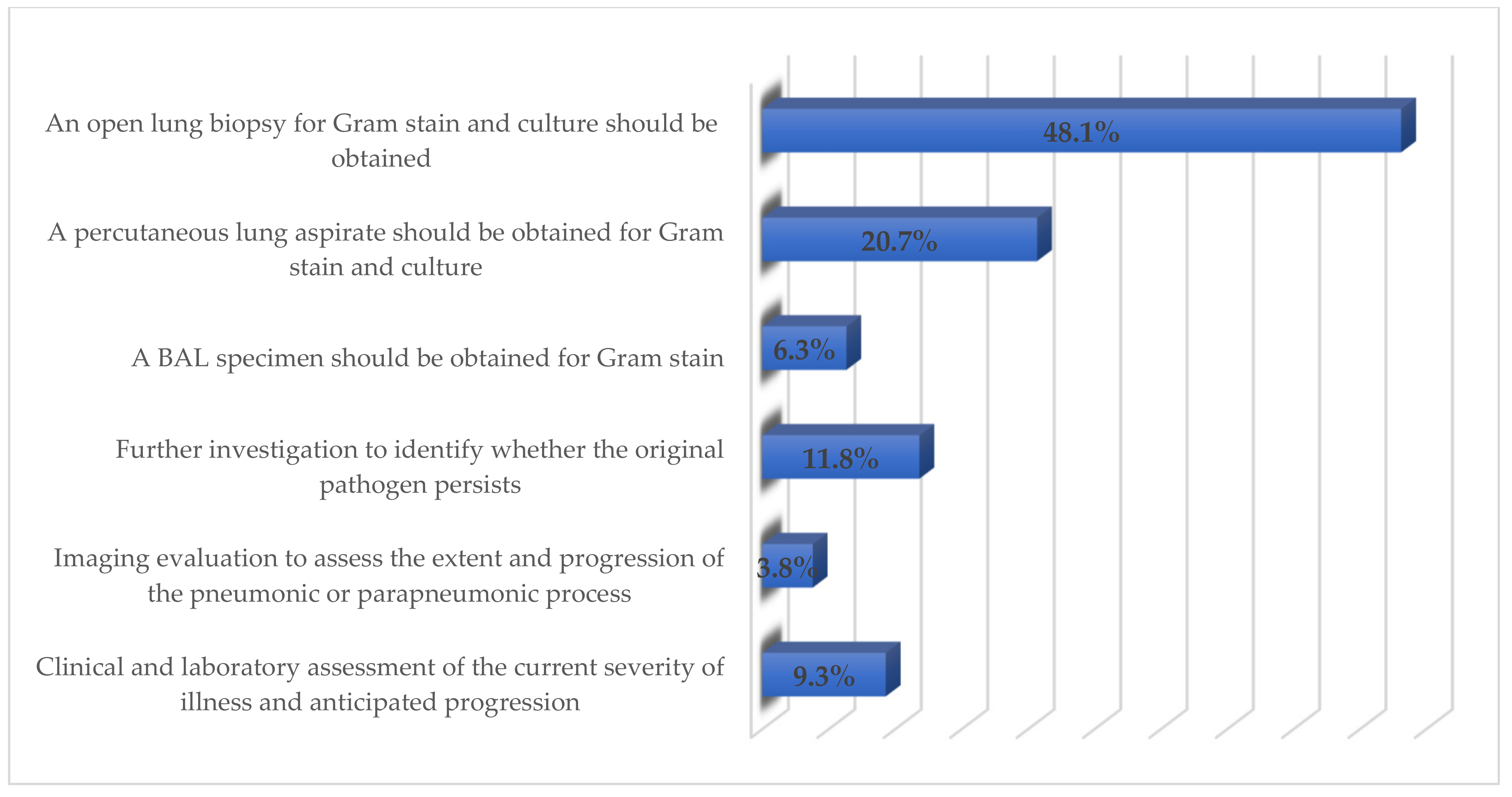

3.5. Respondents’ Perceived ways of Reducing Antimicrobials Resistance through Appropriate Management

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ngocho, J.S.; de Jonge, M.I.; Minja, L.; Olomi, G.A.; Mahande, M.J.; Msuya, S.E.; Mmbaga, B.T. Modifiable risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in children under 5 years of age in resource-poor settings: A case-control study. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2019, 24, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; Principi, N. Defining the aetiology of paediatric community-acquired pneumonia: An unsolved problem. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2019, 13, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.U.; Akhtar, R.J. Community Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) in Children in Developing countries—A Review. North. Int. Med. Coll. J. 2019, 11, 406–410. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, J.A.; Wiemken, T.L.; Peyrani, P.; Arnold, F.W.; Kelley, R.; Mattingly, W.A.; Nakamatsu, R.; Pena, S.; Guinn, B.E.; Furmanek, S.P.; et al. Adults hospitalized with pneumonia in the United States: Incidence, epidemiology, and mortality. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 65, 1806–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, S.; Rizvi, N.; Bhura, S.; Warraich, U.A. Management of community acquired pneumonia by Family Physicians. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 33, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, J.S.; Byington, C.L.; Shah, S.S.; Alverson, B.; Carter, E.R.; Harrison, C.; Kaplan, S.L.; Mace, S.E.; McCracken, G.H.; Moore, M.R., Jr.; et al. The management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: Clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, e25–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cillóniz, C.; Dominedò, C.; Torres, A. Multidrug resistant gram-negative bacteria in community-acquired pneumonia. Crit. Care. 2019, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omair, A. Sample size estimation and sampling techniques for selecting a representative sample. J. Health Special 2014, 2, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.T.; Tran, H.T.; Truong, H.T.; Nguyen, V.T.; Graham, S.M.; Marais, B.J. Paediatric use of antibiotics in children with community acquired pneumonia: A survey from Da Nang, Vietnam. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2019, 55, 1329–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishman, N. America SfHEo, America IDSo. Policy statement on antimicrobial stewardship by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA), the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA), and the pediatric infectious diseases society (PIDS). Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2012, 33, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, S.; Nesar, S.; Rahim, N.; Iffat, W.; Ahmed, H.F.; Rizvi, M. Utilization and impact of electronic and print media on the patients’ health status: Physicians’ perspectives. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2017, 9, 266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.I.; Johnson, T.P.; VanGeest, J.B. Enhancing surveys of health care professionals: A meta-analysis of techniques to improve response. Eval. Health Prof. 2013, 36, 382–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brtnikova, M.; Crane, L.A.; Allison, M.A.; Hurley, L.P.; Beaty, B.L.; Kempe, A. A method for achieving high response rates in national surveys of US primary care physicians. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdács, M.; Albericio, F. Antibiotic Resistance: From the Bench to Patients. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, J.S.; Ross, R.K.; Bryan, M.; Localio, A.R.; Szymczak, J.E.; Wasserman, R.; Barkman, D.; Odeniyi, F.; Conaboy, K.; Bell, L.; et al. Association of broad-vs narrow-spectrum antibiotics with treatment failure, adverse events, and quality of life in children with acute respiratory tract infections. JAMA 2017, 318, 2325–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queen, M.A.; Myers, A.L.; Hall, M.; Shah, S.S.; Williams, D.J.; Auger, K.A. Comparative effectiveness of empiric antibiotics for community-acquired pneumonia. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e23–e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.T.; Tran, H.T.; Tran, T.S.; Fitzgerald, D.A.; Graham, S.M.; Marais, B.J. Predictors of unlikely bacterial pneumonia and adverse pneumonia outcome in children admitted to a hospital in central Vietnam. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 70, 1733–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yogo, N.; Shihadeh, K.; Young, H.; Calcaterra, S.; Knepper, B.C.; Burman, W.J. Intervention to reduce broad-spectrum antibiotics and treatment durations prescribed at the time of hospital discharge: A novel stewardship approach. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2017, 38, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdács, M.; Szabó, A. Physicians’ opinions towards antibiotic use and resistance in the Southeastern Region of Hungary. Orvosi Hetilap 2020, 161, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, C.-C.; Shen, C.-F.; Chen, S.-J.; Chen, H.-M.; Wang, Y.-C.; Chang, W.-S.; Chang, Y.-T.; Chen, W.-Y.; Huang, C.-Y.; Kuo, C.-C.; et al. Recommendations and guidelines for the treatment of pneumonia in Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2019, 52, 172–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, S.; Fuchs, A.; Bielicki, J.; Van Den Anker, J.; Sharland, M. Antibiotic use for community-acquired pneumonia in neonates and children: WHO evidence review. Paediatr. Int. Child Health 2018, 38 (Suppl. S1), S66–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson-Hahn, E.E.; Mickan, S.; Onakpoya, I.; Roberts, N.; Kronman, M.; Butler, C.C. Short-course versus long-course oral antibiotic treatment for infections treated in outpatient settings: A review of systematic reviews. Fam. Pract. 2017, 34, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginsburg, A.-S.; Mvalo, T.; Nkwopara, E.; McCollum, E.D.; Phiri, M.; Schmicker, R.; Hwang, J.; Nadamala, C.B.; Phiri, A.; Lufesi, N.; et al. Amoxicillin for 3 or 5 days for chest-indrawing pneumonia in Malawian children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, F.M.; Reyburn, R.; Chan, J.; Tuivaga, E.; Lim, R.; Lai, J.; Van, H.M.T.; Choummanivong, M.; Sychareun, V.; Khanh, D.K.T.; et al. Impact of the change in WHO’s severe pneumonia case definition on hospitalized pneumonia epidemiology: Case studies from six countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 2019, 97, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addo-Yobo, E.; Anh, D.D.; El-Sayed, H.F.; Fox, L.M.; Fox, M.P.; MacLeod, W.; Saha, S.; Tuan, T.A.; Thea, D.M.; Qazi, S.; et al. Outpatient treatment of children with severe pneumonia with oral amoxicillin in four countries: The MASS study. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2011, 16, 995–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pernica, J.M.; Harman, S.; Kam, A.J.; Carciumaru, R.; Vanniyasingam, T.; Crawford, T.; Dalgleish, D.; Khan, S.; Slinger, R.S.; Fulford, M.; et al. Short-course antimicrobial therapy for pediatric community-acquired pneumonia: The SAFER randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, F.; Wang, B.; Liu, L.; Hou, W. Overprescribing in China, driven by financial incentives, results in very high use of antibiotics, injections, and corticosteroids. Health Aff. 2012, 31, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.W.; Lee, T.-L. Global Governance of Anti-Microbial Resistance: A legal and Regulatory Toolkit. Ethics and Drug Resistance: Collective Responsibility for Global Public Health; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2020; pp. 401–420. [Google Scholar]

- Om, C.; Vlieghe, E.; McLaughlin, J.C.; Daily, F.; McLaws, M.-L. Antibiotic prescribing practices: A national survey of Cambodian physicians. Am. J. Infect. Control 2016, 44, 1144–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox-Lewis, S.; Pol, S.; Miliya, T.; Day, N.P.; Turner, P.; Turner, C. Utilization of a clinical microbiology service at a Cambodian paediatric hospital and its impact on appropriate antimicrobial prescribing. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillekeratne, L.G.; Bodinayake, C.K.; Nagahawatte, A.; Vidanagama, D.; Devasiri, V.; Arachchi, W.K.; Kurukulasooriya, R.; Silva, A.D.D.; Østbye, T.; Reller, M.E.; et al. Use of rapid influenza testing to reduce antibiotic prescriptions among outpatients with influenza-like illness in southern Sri Lanka. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015, 93, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, N.T.; Ta, N.T.; Tran, N.T.; Than, H.M.; Vu, B.T.; Hoang, L.B.; Doorn, H.R.; Vu, D.T.; Cals, J.W.; Chandna, A.; et al. Point-of-care C-reactive protein testing to reduce inappropriate use of antibiotics for non-severe acute respiratory infections in Vietnamese primary health care: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e633–e641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernet, G.; Mary, C.; Altmann, D.M.; Doumbo, O.; Morpeth, S.; Bhutta, Z.A. Surveillance for antimicrobial drug resistance in under-resourced countries. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Frequency (n; %) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 101 (42.6) |

| Female | 136 (57.3) | |

| Age | <30 years | 163 (68.7) |

| 30–39 years | 69 (29.1) | |

| 40–49 years | 5 (2.1) | |

| Type of Working Hospital | Private | 86 (36.2) |

| Public sector | 151 (63.7) | |

| Experience | <1 year | 62 (26.1) |

| 1–5 years | 123 (51.8) | |

| 5–10 years | 47 (19.8) | |

| 10–15 years | 4 (1.6) | |

| >15 years | 1 (0.4) | |

| Use antibiotics extensively in clinical practice | Yes | 225 (94.9) |

| No | 12 (5.0) | |

| Preferable route of antibiotic administration | Oral | 180 (75.9) |

| Intravenous (IV) | 45 (18.9) | |

| Intramuscular (IM) | 12 (5.0) | |

| Would you manage a child with a presumed viral LRT infection with antibiotics? | Yes | 77 (32.4) |

| No | 160 (67.5) | |

| Do you know the adverse effects associated with the use of antibiotics in children? | Yes | 231 (97.4) |

| No | 5 (2.1) | |

| Scenario | Antibiotic Choice | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Priority, n (%) | Second Priority, n (%) | Third Priority, n (%) | Other Priorities, n (%) | |

| Non-Severe Pneumonia | ||||

| Outpatient | Amoxicillin | Amoxicillin clavulanate | Macrolide | |

| 122 (51.5) | 81 (34.2) | 25 (10.5) | 9 (3.7) | |

| Inpatient | Non-Severe Pneumonia | |||

| Without previous use of antibiotic | Amoxicillin | Amoxicillin clavulanate | Macrolide | |

| 100 (42.2) | 93 (39.2) | 33 (13.9) | 11 (4.6) | |

| With previous use of antibiotic | Macrolide | Cephalosporin 2nd generation | Amoxicillin clavulanate | |

| 95 (40.0) | 90 (37.9) | 44(18.5) | 8 (3.3) | |

| Severe Pneumonia | ||||

| Without previous use of antibiotic | Cephalosporin (3rd generation) | Ampicillin or penicillin G | Gentamycin | |

| 155 (65.4) | 62 (26.1) | 11 (4.6) | 9 (3.7) | |

| With previous use of antibiotic | Cephalosporin (3rd generation) | Ampicillin or penicillin G | Gentamycin | |

| 184 (77.6) | 26 (11.0) | 15 (6.3) | 12 (5.0) | |

| Length of Hospitalization and Intravenous Use of Antibiotic | No. of Days | Frequency (n; %) |

|---|---|---|

| Duration of hospital stay in non-severe pneumonia | <3 days | 66 (27.8) |

| 3–5 days | 143 (60.5) | |

| 6–7 days | 21 (8.8) | |

| 8–10 days | 7 (2.9) | |

| Duration of hospital stay in severe pneumonia | <5 days | 14 (5.9) |

| 6–7 days | 115 (48.5) | |

| 8–10 days | 73 (30.8) | |

| 11–14 days | 35 (14.6) | |

| IV antibiotics to a child with severe pneumonia | <3 days | 1 (0.4) |

| 3–5 days | 82 (34.5) | |

| 6–7 days | 128 (54.0) | |

| 8–10 days | 26 (10.9) |

| Decision | Strength of Influencing Factor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | Third | ||

| Antibiotic prescribing behavior | National guidelines | Local Expert opinion | Best available drug | Other factors |

| 180 (75.9) | 29 (12.2) | 21 (8.9) | 7 (2.9) | |

| Hospital discharge | Clinical Assessment | Complete IV Antibiotic course | Parental request | Other factors |

| 197 (83.1) | 19 (8.0) | 9 (3.8) | 12 (5.0) | |

| Statement | Strongly Agree/Agree n (%) | Neutral n (%) | Disagree/Strongly Disagree n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child or Infant with CAP who Must Be Hospitalized | |||

| A child with moderate to severe CAP must be hospitalized for better clinical care | 235 (99.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.8) |

| Children of age <6 months with suspected bacterial CAP are likely to get better therapeutic care by hospitalization | 214 (90.2) | 20 (8.4) | 3 (1.2) |

| Children with suspected CAP caused by an increased virulence pathogen, for instance, community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) | 204 (86.0) | 19 (8.0) | 9 (3.7) |

| Children who lack vigilant observation at home or incapable of following the recommended therapy | 192 (81.0) | 27 (11.3) | 13 (5.4) |

| Anti-Infective Treatment | |||

| Antibiotic is not compulsory for a preschool-aged CAP child, as commonly, the infection is caused by virus. | 172 (72.6) | 31 (13.1) | 34 (14.3) |

| Amoxicillin must be used as the first choice for immunized infants and toddlers who were previously healthy and have minor to moderate bacterial CAP. | 210 (88.6) | 17 (7.1) | 9 (3.7) |

| Amoxicillin provides suitable coverage for Streptococcus pneumoniae. | 185 (78.0) | 29 (12.2) | 23 (9.7) |

| Macrolide antibiotics must be given for the management of a child with CAP caused by atypical pathogens in an outpatient setting. | 185 (78.0) | 38 (16.0) | 13 (5.4) |

| Influenza antiviral treatment should be directed as prompt as possible to a child with moderate to severe CAP due to the influenza virus. | 179 (75.5) | 44 (18.5) | 14 (5.9) |

| Ampicillin or penicillin G should be given to the appropriately immunized child admitted in hospital with CAP due to S. pneumoniae. | 168 (70.8) | 40 (16.8) | 29 (12.2) |

| Empiric treatment with a third-generation parenteral cephalosporin should be given for hospitalized infant or child who is not completely vaccinated, or for an infant or child with a life-threatening condition | 186 (78.4) | 43 (18.1) | 8 (3.3) |

| Macrolide along with a β-lactam antibiotic must be given to the hospitalized child for whom Chlamydophila pneumoniae and Mycoplsma pneumoniae are major concerns. | 166 (70.1) | 51 (21.5) | 15 (6.3) |

| Vancomycin or clindamycin should be provided along with β-lactam treatment if the infection is due to Staphylococcus aureus. | 190 (80.1) | 36 (15.1) | 11 (4.6) |

| A child on appropriate therapy must reveal indications of improvement within 48–72 h. | 182 (76.7) | 33 (13.9) | 22 (9.2) |

| A child whose illness worsens after admission or who did not show any progress within 48–72 h needs additional examination. | 206 (86.9) | 28 (11.8) | 3 (1.2) |

| Outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy should be given only to those children who do need nursing attention in an acute care setting; however, their ongoing parenteral treatment is necessary. | 178 (75.1) | 37 (15.6) | 17 (7.1) |

| Switching to oral therapy whenever possible is preferential to parenteral outpatient treatment. | 183 (77.2) | 41 (17.2) | 13 (5.4) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shakeel, S.; Iffat, W.; Qamar, A.; Ghuman, F.; Yamin, R.; Ahmad, N.; Ishaq, S.M.; Gajdács, M.; Patel, I.; Jamshed, S. Pediatricians’ Compliance to the Clinical Management Guidelines for Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Infants and Young Children in Pakistan. Healthcare 2021, 9, 701. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060701

Shakeel S, Iffat W, Qamar A, Ghuman F, Yamin R, Ahmad N, Ishaq SM, Gajdács M, Patel I, Jamshed S. Pediatricians’ Compliance to the Clinical Management Guidelines for Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Infants and Young Children in Pakistan. Healthcare. 2021; 9(6):701. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060701

Chicago/Turabian StyleShakeel, Sadia, Wajiha Iffat, Ambreen Qamar, Faiza Ghuman, Rabia Yamin, Nausheen Ahmad, Saqib Muhammad Ishaq, Márió Gajdács, Isha Patel, and Shazia Jamshed. 2021. "Pediatricians’ Compliance to the Clinical Management Guidelines for Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Infants and Young Children in Pakistan" Healthcare 9, no. 6: 701. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060701

APA StyleShakeel, S., Iffat, W., Qamar, A., Ghuman, F., Yamin, R., Ahmad, N., Ishaq, S. M., Gajdács, M., Patel, I., & Jamshed, S. (2021). Pediatricians’ Compliance to the Clinical Management Guidelines for Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Infants and Young Children in Pakistan. Healthcare, 9(6), 701. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060701