Mental Health, Information and Being Connected: Qualitative Experiences of Social Media Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic from a Trans-National Sample

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Setting

2.3. Questionnaire

2.4. Survey Question

2.5. Analysis

Rigor

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

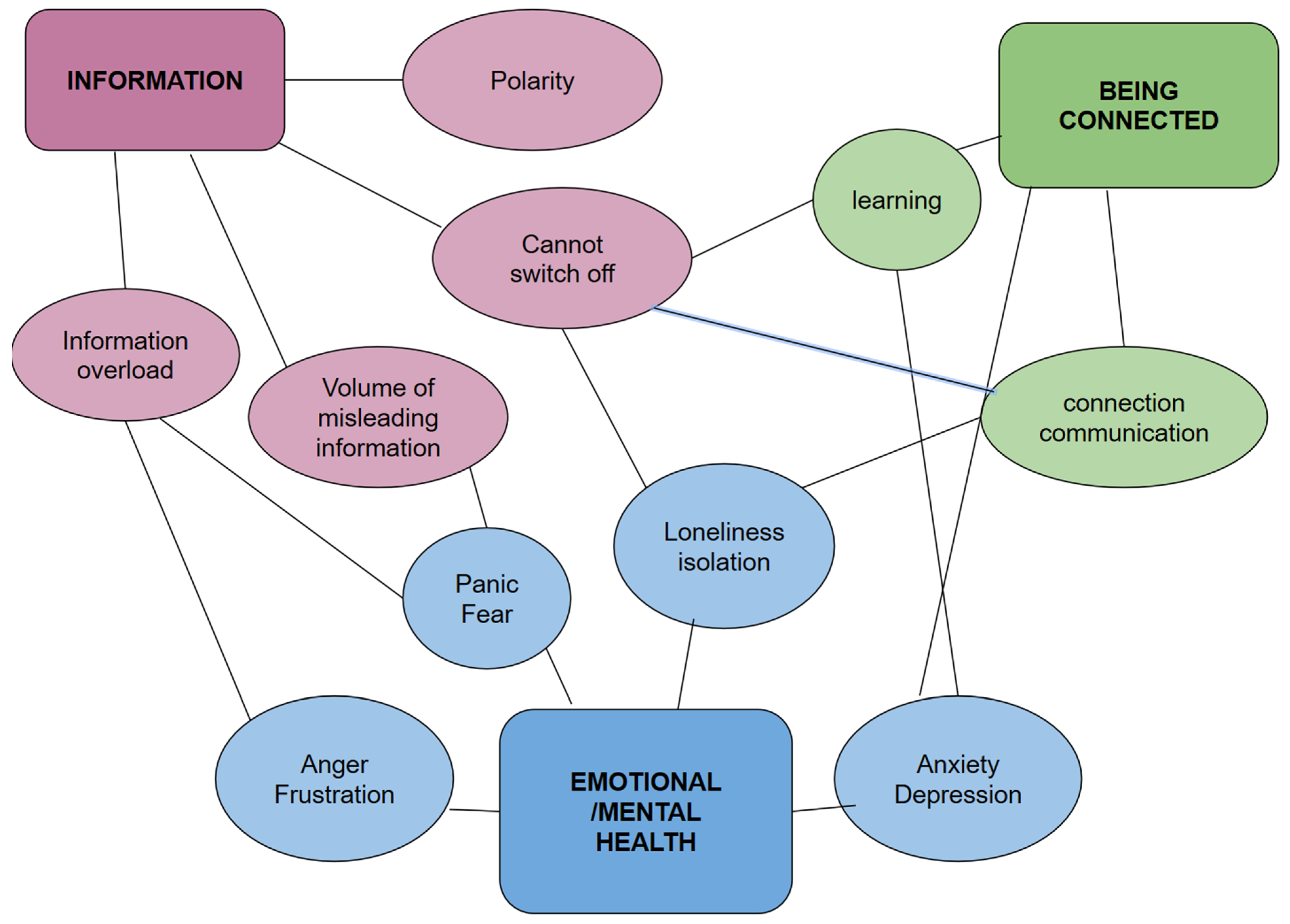

3.2. Themes Emerged

3.3. Emotional and Mental Health

3.3.1. Anxiety and/or Depression

3.3.2. Anger and/or Frustration

3.3.3. Panic and/or Fear

3.3.4. Loneliness and/or Isolation

3.4. Information

3.4.1. Information Overload

3.4.2. Volume of Misleading Information

3.4.3. Polarity

3.4.4. Cannot Switch Off

3.5. Being Connected

3.5.1. Connection/Communication

3.5.2. Learning

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Implications for Policy and Practice

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| USA | United States of America |

| SARS | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix A

| Country | Summary of Policies |

|---|---|

| USA * | 17 March to 4 April, extended to 30 April: stay at home order across states, earliest in California, Illinois, and Puerto Rico; gathering ban with most states restricted to 10 or less for all gatherings; school closures; bars, sit-down restaurants and non-essential retail closed for most states. |

| UK | 18 March: schools closed; 21 March: entertainment venues closed; 24 March: full lockdown imposed; ban on public gatherings of more than two people (excluding members of the same household); close-down of all non-essential services; directions to stay at home other than for essential reasons. |

| Australia * | 21 March: social distancing rules imposed and state governments to start closing non-essential services; 29 March: national announcement of restrictions on public gatherings of more than two people (excluding members of the same household); directions to stay at home other than for essential reasons); school closures have not been ordered but various arrangements were imposed across the states that brought the school holidays forward; 15 May: public gathering rules for some states are beginning to ease and restricted non-essential services are permitted. |

References

- Prime Minister’s Office. PM Statement on Coronavirus 12 March. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-statement-on-coronavirus-12-march (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- World Health Organization. The WHO Special Initiative for Mental Health (2019–2023): Universal Health Coverage for Mental Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Institute of Public Health. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health Specifies Advice on Social Distancing. 2020. Available online: https://www.fhi.no/nyheter/2020/fhi-presiserer-rad-om-sosial-distansering (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- Tognotti, E. Lessons from the History of Quarantine, from Plague to Influenza A. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.; Smith, E.L.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mukhtar, S. Psychological health during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic outbreak. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torales, J.; O’Higgins, M.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; Ventriglio, A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reblin, M.; Uchino, B.N. Social and emotional support and its implication for health. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2008, 21, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, B.; Li, R.; Lu, Z.; Huang, Y. Does comorbidity increase the risk of patients with COVID-19: Evidence from me-ta-analysis. Aging (Albany N. Y.) 2020, 12, 6049–6057. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, L.F.; Glass, T.; Brissette, I.; Seeman, T.E. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.J.D.; Chang, S.-H.; Yu, Y.-Y. A Support Group for Home-Quarantined College Students Exposed to SARS: Learning from Practice. J. Spéc. Group Work 2005, 30, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, G.J.; Harper, S.; Williams, P.D.; Öström, S.; Bredbere, S.; Amlôt, R.; Greenberg, N. How to support staff deploying on overseas humanitarian work: A qualitative analysis of responder views about the 2014/15 West African Ebola outbreak. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2016, 7, 30933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, G.J.; Brewin, C.R.; Greenberg, N.; Simpson, J.; Wessely, S. Psychological and behavioural reactions to the bombings in London on 7 July 2005: Cross sectional survey of a representative sample of Londoners. BMJ 2005, 331, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manuell, M.-E.; Cukor, J. Mother Nature versus human nature: Public compliance with evacuation and quarantine. Disasters 2010, 35, 417–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunder, R.; Hunter, J.; Vincent, L.; Bennett, J.; Peladeau, N.; Leszcz, M.; Sadavoy, J.; Verhaeghe, L.M.; Steinberg, R.; Mazzulli, T. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2003, 168, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar]

- Depoux, A.; Martin, S.; Karafillakis, E.; Preet, R.; Wilder-Smith, A.; Larson, H. The Pandemic of Social Media Panic Travels Faster Than the COVID-19 Outbreak. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kulshrestha, J.; Eslami, M.; Messias, J.; Zafar, M.B.; Ghosh, S.; Gummadi, K.P.; Karahalios, K. Quan-tifying search bias: Investigating sources of bias for political searches in social media. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Portland, OR, USA, 25 February–1 March 2017; pp. 417–432. [Google Scholar]

- Cinelli, M.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Galeazzi, A.; Valensise, C.M.; Brugnoli, E.; Schmidt, A.L.; Zola, P.; Zollo, F.; Scala, A. The covid-19 social media info-demic. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starnini, M.; Frasca, M.; Baronchelli, A. Emergence of metapopulations and echo chambers in mobile agents. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Merchant, R.M.; Lurie, N. Social Media and Emergency Preparedness in Response to Novel Coronavirus. JAMA 2020, 323, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thompson, R.R.; Garfin, D.R.; Holman, E.A.; Silver, R.C. Distress, worry, and functioning following a global health crisis: A national study of Americans’ responses to Ebola. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 5, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bendau, A.; Petzold, M.B.; Pyrkosch, L.; Maricic, L.M.; Betzler, F.; Rogoll, J.; Große, J.; Ströhle, A.; Plag, J. Associations between COVID-19 related media consumption and symptoms of anxiety, depression and COVID-19 related fear in the general population in Germany. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 271, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopelliti, M.; Pacilli, M.G.; Aquino, A. TV News and COVID-19: Media Influence on Healthy Behavior in Public Spaces. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.K.M.; Nickson, C.P.; Rudolph, J.W.; Lee, A.; Joynt, G.M. Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: Early experi-ence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.; Payel, B.; Ritwik, G.; Subhankar, C.; Mahua, J.D.; Subham, C.; Durjoy, L.; Carl, J.L. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geirdal, A.Ø.; Ruffolo, M.; Leung, J.; Thygesen, H.; Price, D.; Bonsaksen, T.; Schoultz, M. Mental health, quality of life, wellbeing, loneliness and use of social media in a time of social distancing during the COVID-19 outbreak. A cross-country comparative study. J. Ment. Health 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utne, I.; Småstuen, M.C.; Nyblin, U. Pain Knowledge and Attitudes Among Nurses in Cancer Care in Norway. J. Cancer Educ. 2018, 34, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiran, S.; Cherney, L.R.; Kagan, A.; Haley, K.L.; Antonucci, S.M.; Schwartz, M.; Holland, A.L.; Simmons-Mackie, N. Aphasia assessments: A survey of clinical and research settings. Aphasiology 2018, 32, 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A.S.; Stephenson, J.; Williams, A.E. A survey of people with foot problems related to rheumatoid arthritis and their educational needs. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2017, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative research. In Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science; Wiley Online Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, I.C.-H.; Tse, Z.T.H.; Cheung, C.-N.; Miu, A.S.; Fu, K.-W. Ebola and the social media. Lancet 2014, 384, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seltzer, E.K.; Jean, N.; Kramer-Golinkoff, E.; Asch, D.A.; Merchant, R. The content of social media’s shared images about Ebola: A retrospective study. Public Health 2015, 129, 1273–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Zheng, P.; Jia, Y.; Chen, H.; Mao, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Fu, H.; Dai, J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.S.; Chee, C.Y.; Ho, R.C. Mental Health Strategies to Combat the Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Beyond Paranoia and Panic. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2020, 49, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.E.; Jung, K.; Park, H.W. Social media use during Japan’s 2011 earthquake: How Twitter transforms the locus of crisis communication. Media Int. Aust. 2013, 149, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalbers, G.; McNally, R.J.; Heeren, A.; De Wit, S.; Fried, E.I. Social media and depression symptoms: A network perspective. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2019, 148, 1454–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zarocostas, J. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet 2020, 395, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, G. How to Fight an Infodemic: The Four Pillars of Infodemic Management. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e21820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, A.D.; Guillory, J.E.; Hancock, J.T. Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social net-works. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8788–8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taylor, M.; Wells, G.; Howell, G.; Raphael, B. The role of social media as psychological first aid as a support to community resilience building. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2012, 27, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Neubaum, G.; Rösner, L.; der Pütten, A.R.-V.; Krämer, N.C. Psychosocial functions of social media usage in a disaster situation: A multi-methodological approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 34, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimé, B. Emotion Elicits the Social Sharing of Emotion: Theory and Empirical Review. Emot. Rev. 2009, 1, 60–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nils, F.; Rimé, B. Beyond the myth of venting: Social sharing modes determine the benefits of emotional disclosure. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, P.; Cai, Q.; Jiang, W.; Chan, K. Engagement of Government Social Media on Facebook during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Macao. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, M.L.; Taylor, M. Building dialogic relationships through the world wide web. Public Relat. Rev. 1998, 24, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Min, C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, G.; Ma, X.; Evans, R. Unpacking the black box: How to promote citizen engagement through government social media during the COVID-19 crisis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 110, 106380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirtz, J.G.; Zimbres, T.M. A systematic analysis of research applying ‘principles of dialogic communication’to organizational websites, blogs, and social media: Implications for theory and practice. J. Public Relat. Res. 2018, 30, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghebreyesus, T.A. Safeguard research in the time of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 443. [Google Scholar]

- Ghebreyesus, T.A. Addressing mental health needs: An integral part of COVID-19 response. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 129–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Emotional/mental health | Anxiety, depression |

| Anger, frustration | |

| Panic, fear | |

| Loneliness, isolation | |

| Information | Information overload |

| Volume of misleading information | |

| Polarity | |

| Cannot switch off | |

| Being connected | Connection, communication |

| Learning |

| Total | UK | USA | Australia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1991 | n = 1013 | n = 801 | n = 177 | |

| Age group | ||||

| 18–29 | 18.5% | 16.4% | 18.4% | 30.5% |

| 30–39 | 18.5% | 18.1% | 19.2% | 17.5% |

| 40–49 | 20.7% | 24.3% | 17.2% | 15.8% |

| 50–59 | 20.8% | 22.8% | 18.7% | 18.6% |

| 60+ | 21.6% | 18.5% | 26.5% | 17.5% |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 80.9% | 85.4% | 75.9% | 77.4% |

| Male | 17.0% | 13.2% | 21.3% | 19.2% |

| Other/prefer not to say | 2.2% | 1.4% | 2.9% | 3.4% |

| Area of residence | ||||

| Rural or Farming | 7.2% | 5.7% | 10.1% | 2.3% |

| Small town | 22.2% | 16.8% | 31.1% | 13.0% |

| Medium-Sized City | 37.0% | 37.9% | 40.8% | 14.7% |

| Large City | 33.6% | 39.6% | 18.0% | 70.1% |

| Education | ||||

| High school or below | 8.7% | 7.7% | 9.5% | 10.8% |

| Technical/Associate degree | 19.2% | 23.2% | 13.1% | 24.4% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 32.4% | 34.1% | 32.7% | 21.6% |

| Master’s/Doctoral degree | 39.6% | 35.0% | 44.7% | 43.2% |

| Live with someone | ||||

| Yes | 82.0% | 83.0% | 80.2% | 84.7% |

| No | 18.0% | 17.0% | 19.8% | 15.3% |

| Currently in work | ||||

| Yes, in a Full-time job | 45.9% | 46.2% | 46.6% | 40.7% |

| Yes, in a Part-time job | 22.1% | 23.8% | 17.4% | 34.5% |

| No | 32.0% | 30.0% | 36.1% | 24.9% |

| How often have you used social media after COVID-19 pandemic started? | ||||

| Weekly or less | 1.6% | 1.7% | 1.3% | 2.3% |

| A few times a week | 3.0% | 3.8% | 1.8% | 3.4% |

| Daily | 24.5% | 26.2% | 20.6% | 32.8% |

| Several times daily | 70.9% | 68.3% | 76.4% | 61.6% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schoultz, M.; Leung, J.; Bonsaksen, T.; Ruffolo, M.; Thygesen, H.; Price, D.; Geirdal, A.Ø. Mental Health, Information and Being Connected: Qualitative Experiences of Social Media Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic from a Trans-National Sample. Healthcare 2021, 9, 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060735

Schoultz M, Leung J, Bonsaksen T, Ruffolo M, Thygesen H, Price D, Geirdal AØ. Mental Health, Information and Being Connected: Qualitative Experiences of Social Media Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic from a Trans-National Sample. Healthcare. 2021; 9(6):735. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060735

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchoultz, Mariyana, Janni Leung, Tore Bonsaksen, Mary Ruffolo, Hilde Thygesen, Daicia Price, and Amy Østertun Geirdal. 2021. "Mental Health, Information and Being Connected: Qualitative Experiences of Social Media Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic from a Trans-National Sample" Healthcare 9, no. 6: 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060735

APA StyleSchoultz, M., Leung, J., Bonsaksen, T., Ruffolo, M., Thygesen, H., Price, D., & Geirdal, A. Ø. (2021). Mental Health, Information and Being Connected: Qualitative Experiences of Social Media Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic from a Trans-National Sample. Healthcare, 9(6), 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060735