The Rising Burden of Diabetes-Related Blindness: A Case for Integration of Primary Eye Care into Primary Health Care in Eswatini

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

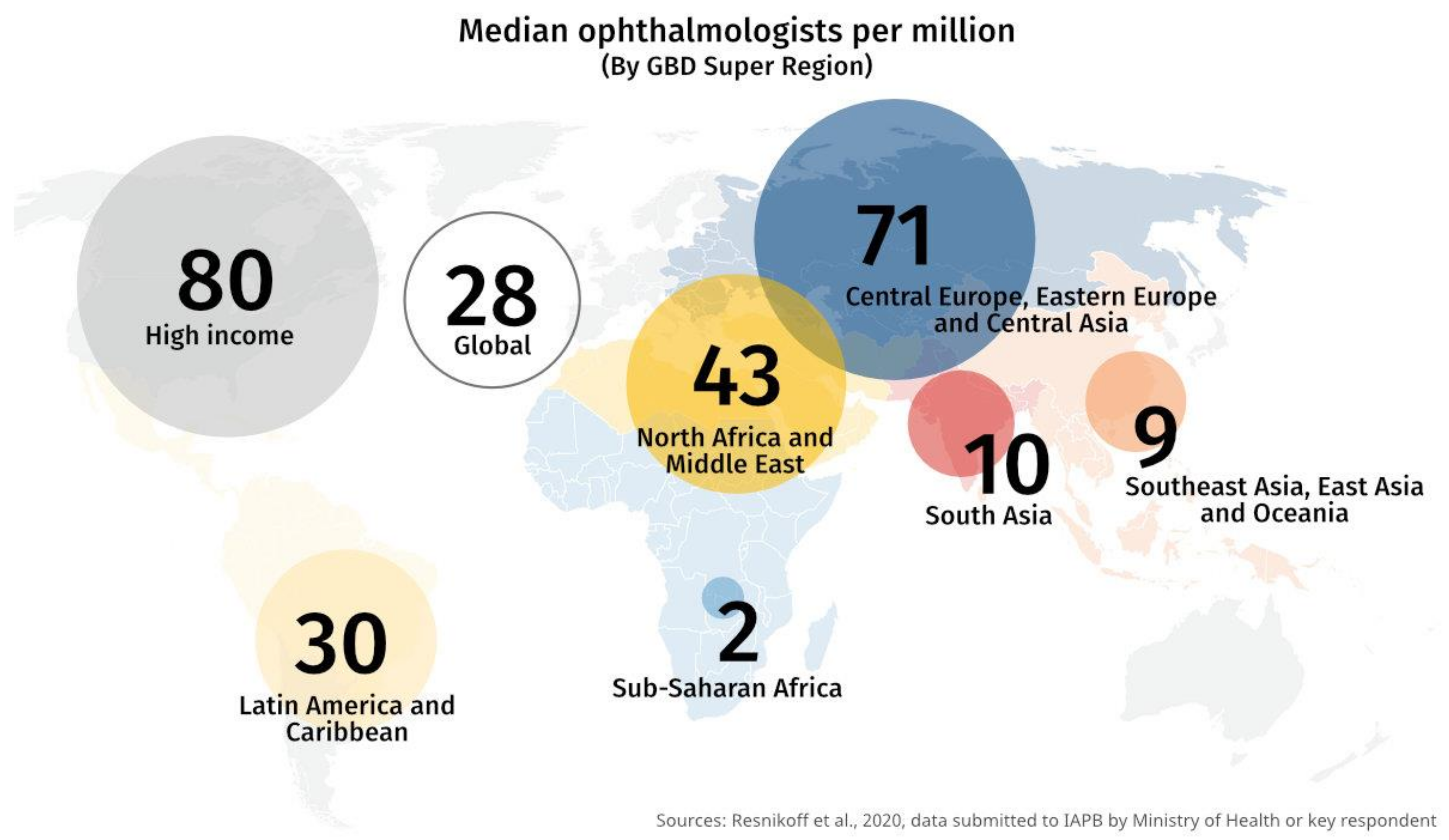

3.1. The State of Eye Health in Developing Countries

3.2. A Focus on Eye Care Services in The Kingdom of Eswatini

3.3. The Role of Primary Health Care

3.4. The Role of Primary Eye Care

3.5. Primary Eye Care in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Lack of a unanimous definition of PEC and a lack of clear guidelines on technical eye-related skills required by PHC workers. Consequently, there is disagreement on the type of equipment and consumables needed as well as the scope of training, support and supervision necessary for PEC [61].

- Lack of appropriate PEC skills and low productivity amongst PHC workers, diminished trust in the PEC services by targeted communities.

- Common causes of vision impairment, i.e., (immature) cataract, glaucoma, DR and refractive errors are often beyond the capacity of the general doctor or nurse. Equipment required by an eye specialist to diagnose these conditions is not available at PHC level [58]. The use of mobile eye care teams may assist in bridging this gap. A study in South Africa, for example, found that a technician who visited PHC facilities with a mobile camera was not only able to detect DR but also cataract cases needing surgery [62].

- Despite improved supervision, “persistent deficiencies in the diagnosis and treatment of common eye conditions” was found to be a major problem across three SSA countries (Kenya, Malawi and Tanzania) [58]. Courtright et al. stated that it is important for supervisors to have technical skills that match those required of the PHC worker. External support is also highlighted as beneficial in the provision of basic equipment and technical training [61].

3.6. Integration of Primary Health Care and Primary Eye Care Services

- Is it desirable? Will there be an added valuable output from integrating an intervention into the general health service package?

- Is integration possible? Would general health workers have the ability to perform the task appropriately and with a level of standardization? This is particularly a key question in many developing countries, where the health workforce is limited and where community and primary health care workers, in particular, are often overburdened with a range of activities targeting various interventions. This leads to poor quality of services and poor health outcomes [30].

- “Is it opportune to integrate?” In other words, does the general health service have the capacity in terms of human resource, equipment and supplies, etc. to accommodate an additional activity? In some cases, one may argue that perhaps integration may constitute a strong case for maximizing the current capacity of a general health service. The need to thoroughly interrogate and address these questions is imperative to ensure that integration is sustainable and does not lead to the further weakening of a health system.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Report on Diabetes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 978–988. ISBN 978-92-4-156525-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ogurtsova, K.; da Rocha Fernandes, J.D.; Huang, Y.; Linnenkamp, U.; Guariguata, L.; Cho, N.H.; Cavan, D.; Shaw, J.E.; Makaroff, L.E. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 128, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beran, D.; Yudkin, J.S. Diabetes care in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 2006, 368, 1689–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, I.; Yorston, D. Diabetic retinopathy: Everybody’s business. Community Eye Heal. 2011, 24, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, L. Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines: Eye Care of the Patient with Diabetes Mellitus; American Optometric Association: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, R.R.A.; Flaxman, S.R.; Braithwaite, T.; Cicinelli, M.V.; Das, A.; Jonas, J.B.; Keeffe, J.; Kempen, J.H.; Leasher, J.; Limburg, H.; et al. Magnitude, temporal trends, and projections of the global prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2017, 5, e888–e897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Report on Vision; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 214. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Global Action Plan for the Prevention of Avoidable Blindness and Visual Impairment 2014–2019; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, C.; Resnikoff, S. Getting ready to cope with non-communicable eye diseases. Community Eye Heal. 2014, 27, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet, K.; Gilbert, C.; De Savigny, D. Rethinking eye health systems to achieve universal coverage: The role of research. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 98, 1325–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchet, K.; Patel, D. Applying principles of health system strengthening to eye care. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 60, 470–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicinelli, M.V.; Marmamula, S.; Khanna, R.C. Comprehensive eye care-Issues, challenges, and way forward. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 68, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, J.; Landes, M.; Carroll, C.; Nolen, A.; Sodhi, S. A systematic review of primary care models for non-communicable disease interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Fam. Pr. 2017, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.M.S.; Purnat, T.D.; Phuong, N.T.A.; Mwingira, U.; Schacht, K.; Fröschl, G. Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) in developing countries: A symposium report. Glob. Heal. 2014, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst-Hensch, N.; Tanner, M.; Kessler, C.; Burri, C.; Künzli, N. Prevention: A cost-effective way to fight the non-communicable disease epidemic. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011, 141, w13266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non Communicable Diseases; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dunachie, S.; Chamnan, P. The double burden of diabetes and global infection in low and middle-income countries. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 113, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, P.I.; Msukwa, G.; Beare, N.A. Diabetic retinopathy in sub-Saharan Africa: Meeting the challenges of an emerging epidemic. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 1–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastakia, S.D.; Pekny, C.R.; Manyara, S.M.; Fischer, L. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa—From policy to practice to progress: Targeting the existing gaps for future care for diabetes. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obesity: Targets Ther. 2017, 10, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renzaho, A.M.N. The post-2015 development agenda for diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and future directions. Glob. Heal. Action 2015, 8, 27600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalal, S.; Beunza, J.J.; Volmink, J.; Adebamowo, C.; Bajunirwe, F.; Njelekela, M.; Mozaffarian, D.; Fawzi, W.; Willett, W.; Adami, H.-O.; et al. Non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: What we know now. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 40, 885–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yau, J.W.; Rogers, S.L.; Kawasaki, R.; Lamoureux, E.L.; Kowalski, J.W.; Bek, T.; Chen, S.-J.; Dekker, J.M.; Fletcher, A.; Grauslund, J.; et al. Global Prevalence and Major Risk Factors of Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, G.V.; Usha, R. Perspectives on primary eye care. Community Eye Heal J. 2009, 22, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- DeMaio, A.R.; Nielsen, K.K.; Tersbøl, B.P.; Kallestrup, P.; Meyrowitsch, D.W. Primary Health Care: A strategic framework for the prevention and control of chronic non-communicable disease. Glob. Heal. Action 2014, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, R.; Faal, H.B.; Etya’Ale, D.; Wiafe, B.; Mason, I.; Graham, R.; Bush, S.; Mathenge, W.; Courtright, P. Evidence for integrating eye health into primary health care in Africa: A health systems strengthening approach. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, N.S.; Steyn, K.; Dave, J.; Bradshaw, D. Chronic non-communicable diseases and HIV-AIDS on a collision course: Rele-vance for health care delivery, particularly in low-resource settings—Insights from South Africa. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 1690S–1696S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nentwich, M.M. Diabetic retinopathy-ocular complications of diabetes mellitus. World J. Diabetes 2015, 6, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboobaker, S.; Courtright, P. Barriers to Cataract Surgery in Africa: A Systematic Review. Middle East Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 23, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabin, G.; Chen, M.; Espandar, L. Cataract surgery for the developing world. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2008, 19, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, L.; Garner, P. Strategies for integrating primary health services in low- and middle-income countries at the point of delivery (Review). Cochrane database Syst. Rev. 2011, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.E.; Hall, A.B.; Kok, G.; Mallya, J.; Courtright, P. A needs assessment of people living with diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mugo, B.; Nyongo, P. National Strategic Plan for Eye Health and Blindness Prevention in Kenya; Ministry of Health—Republic of Kenya: Nairobi, Kenya, 2012.

- Pons, J.; Burn, H. Diabetic Retinopathy in the Kingdom of Swaziland. Community Eye Health 2015, 28, s18–s21. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon, P.H. The English National Screening Programme for diabetic retinopathy 2003–2016. Acta Diabetol. 2017, 54, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Available online: www.who.org. (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Gilbert, C.; Murthy, G.; Sivasubramaniam, S.; Kyari, F.; Imam, A.; Rabiu, M.; Abdull, M.; Tafida, A. Couching in Nigeria: Prevalence, Risk Factors and Visual Acuity Outcomes. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010, 17, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jolley, E.; Mafwiri, M.; Hunter, J.; Schmidt, E. Integration of eye health into primary care services in Tanzania: A qualitative investigation of experiences in two districts. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.J.; Chinanayi, F.; Gilbert, A.; Pillay, D.; Fox, S.; Jaggernath, J.; Naidoo, K.; Graham, R.; Patel, D.; Blanchet, K. Mapping human resources for eye health in 21 countries of sub-Saharan Africa: Current progress towards VISION 2020. Hum. Resour. Heal. 2014, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness. IAPB Vision Atlas; IAPB: London, UK, 2021; Available online: www.atlas.iapb.org.2021. (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Eswatini Ministry of Health. Eswatini National Eye Care Plan 2019–2022; Eswatini Ministry of Health: Mbabane, Swaziland, 2019.

- Wong, T.Y.; Sun, J.; Kawasaki, R.; Ruamviboonsuk, P.; Gupta, N.; Lansingh, V.C.; Maia, M.; Mathenge, W.; Moreker, S.; Muqit, M.M.; et al. Guidelines on Diabetic Eye Care. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1608–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Mercer, E.; Mason, I. Ophthalmic equipment survey 2010: Preliminary results. Community Eye Heal. 2010, 23, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kyari, F.; Nolan, W.; Gilbert, C. Ophthalmologists’ practice patterns and challenges in achieving optimal management for glaucoma in Nigeria: Results from a nationwide survey. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaziland Central Statistics Office. Swaziland 2017 Population and Housing Census Report; Swaziland Central Statistics Office: Mbabane, Swaziland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Smit, M.; Olney, J.; Ford, N.P.; Vitoria, M.; Gregson, S.; Vassall, A.; Hallett, T.B. The growing burden of noncommunicable disease among persons living with HIV in Zimbabwe. AIDS 2018, 32, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atun, R.; Davies, J.I.; Gale, E.A.M.; Bärnighausen, T.; Beran, D.; Kengne, A.P.; Levitt, N.; Mangugu, F.W.; Nyirenda, M.J.; Ogle, G.D.; et al. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa: From clinical care to health policy. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 622–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabkin, M.; Kruk, M.E.; El-Sadr, W.M. HIV, aging and continuity care. AIDS 2012, 26, S77–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eswatini Ministry of Health. Available online: http://www.gov.sz/index.php/ministries-departments/ministry-of-health (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Eswatini Ministry of Health. National Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs); Eswatini Ministry of Health: Mbabane, Swaziland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Alma Ata 1978: Primary Health Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Druetz, T. Integrated primary health care in low-and middle-income countries: A double challenge. BMC Med Ethic 2018, 19, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global Strategy on People-Centred and Integrated Health Services; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Masupe, T.K.; Ndayi, K.; Tsolekile, L.; Delobelle, P.; Puoane, T. Redefining diabetes and the concept of self-management from a patient’s perspective: Implications for disease risk factor management. Heal. Educ. Res. 2018, 33, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senyonjo, L.; Lindfield, R.; Mahmoud, A.; Kimani, K.; Sanda, S.; Schmidt, E. Ocular Morbidity and Health Seeking Behaviour in Kwara State, Nigeria: Implications for Delivery of Eye Care Services. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.C. Mobile eye-care teams and rural ophthalmology in southern Africa. South Afr. Med. J. 1984, 66, 531–535. [Google Scholar]

- Lilian, R.R.; Railton, J.; Schaftenaar, E.; Mabitsi, M.; Grobbelaar, C.J.; Khosa, N.S.; Maluleke, B.H.; Struthers, H.E.; McIntyre, J.A.; Peters, R.P.H. Strengthening primary eye care in South Africa: An assessment of services and prospective evaluation of a health systems support package. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalua, K.; Gichangi, M.; Barassa, E.; Eliah, E.; Lewallen, S.; Courtright, P. A randomised controlled trial to investigate effects of enhanced supervision on primary eye care services at health centres in Kenya, Malawi and Tanzania. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriamanjato, H.H.; Mathenge, W.; Kalua, K.; Courtright, P.; Lewallen, S. Task shifting in primary eye care: How sensitive and specific are common signs and symptoms to predict conditions requiring referral to specialist eye personnel? Hum. Resour. Heal. 2014, 12, S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaji, E.A.; Gilbert, C.; Ihebuzor, N.; Faal, H. Strengths, challenges and opportunities of implementing primary eye care in Nigeria. BMJ Glob. Heal. 2018, 3, e000846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtright, P.; Seneadza, A.; Mathenge, W.; Eliah, E.; Lewallen, S. Primary eye care in sub-Saharan African: Do we have the evidence needed to scale up training and service delivery? Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2010, 104, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mash, B.; Powell, D.; du Plessis, F.; van Vuuren, U.; Michalowska, M.; Levitt, N. Screening for diabetic retinopathy in primary care with a mobile fundal camera—Evaluation of a South African pilot project. South Afr. Med J. 2007, 97, 1284–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Aghaji, A.; Burchett, H.E.D.; Mathenge, W.; Faal, H.B.; Umeh, R.; Ezepue, F.; Isiyaku, S.; Kyari, F.; Wiafe, B.; Foster, A.; et al. Technical capacities needed to implement the WHO’s primary eye care package for Africa: Results of a Delphi process. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e042979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banfield, M.; Jowsey, T.; Parkinson, A.; Douglas, K.A.; Dawda, P. Experiencing integration: A qualitative pilot study of consumer and provider experiences of integrated primary health care in Australia. BMC Fam. Pr. 2017, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atun, R.; De Jongh, T.; Secci, F.; Ohiri, K.; Adeyi, O. Integration of targeted health interventions into health systems: A conceptual framework for analysis. Heal. Policy Plan. 2009, 25, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criel, B.K.G.; Van der Stuyft, P. A framework for analysing the relationship between disease control programmes and basic health care. Trop Med Int Heal. 2004, 9, A1–A4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortell, S.M.; Addicott, R.; Walsh, N.; Ham, C. The NHS five year forward view: Lessons from the United States in developing new care models. BMJ 2015, 350, h2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS. Five Year Forward View; NHS: Redditch, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, S.; Johnson, M.; Chambers, D.; Sutton, A.; Goyder, E.; Booth, A. The effects of integrated care: A systematic review of UK and international evidence. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neena, J.; Rachel, J.; Praveen, V.; Murthy, G.V.S.; for the RAAB India Study Group. Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness in India. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, G.V. Diabetic Retinopathy Situational Analysis; Indian Institute of Public Health: Hyderabad, India, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashist, P.; Malhotra, S.; Gupta, S.K.; Misra, V. Models for Primary Eye Care Services in India. Indian J. Community Med. 2015, 40, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category 1 | Category 2 | Category 3 | Category 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Models focused on making changes to organizations and systems | Models focused on improving patient care | Models addressing staffing needs and work ethic | Models focused on health financing and governance |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maseko, S.N.; van Staden, D.; Mhlongo, E.M. The Rising Burden of Diabetes-Related Blindness: A Case for Integration of Primary Eye Care into Primary Health Care in Eswatini. Healthcare 2021, 9, 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9070835

Maseko SN, van Staden D, Mhlongo EM. The Rising Burden of Diabetes-Related Blindness: A Case for Integration of Primary Eye Care into Primary Health Care in Eswatini. Healthcare. 2021; 9(7):835. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9070835

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaseko, Sharon Nobuntu, Diane van Staden, and Euphemia Mbali Mhlongo. 2021. "The Rising Burden of Diabetes-Related Blindness: A Case for Integration of Primary Eye Care into Primary Health Care in Eswatini" Healthcare 9, no. 7: 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9070835

APA StyleMaseko, S. N., van Staden, D., & Mhlongo, E. M. (2021). The Rising Burden of Diabetes-Related Blindness: A Case for Integration of Primary Eye Care into Primary Health Care in Eswatini. Healthcare, 9(7), 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9070835