Optimizing Therapies in Heart Failure: The Role of Potassium Binders

Abstract

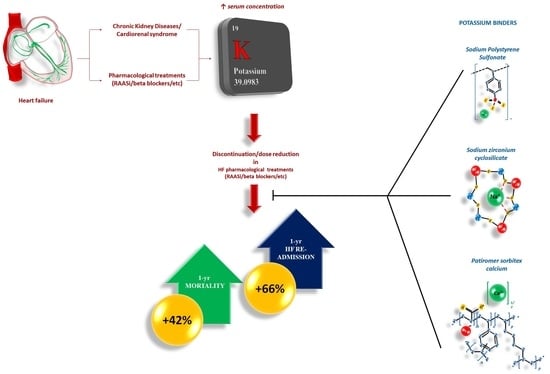

:1. Introduction

2. Search Strategies

3. Hyperkalemia in HF: Definition, Prevalence, and Prognosis

4. Treatment of Hyperkalemia: Advances in Therapies

4.1. Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate

| Study | N. of pts | Type of pts | Design | Approach | Follow-Up | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batterink et al., 2015 [33] | 138 | Serum K+ between 5.0 and 5.9 mEq/L | Retrospective observational study | 72 control group 66 treatment group (dose 15 or 30 g) | 24 h | ΔK+ 6 h: −0.44 ± 0.29 mEq/L; ΔK+ 24 h: −0.58 ± 0.39 mEq/L (p = 0.026) No difference between patients 15 and 30 g of SPS |

| Lepage et al., 2015 [34] | 33 | Outpatients with CKD and serum K+ between 5.0 and 5.9 mEq/L | RCT | Placebo or SPS 30 g orally o.d. for 7 days | 7 days | SPS ↓ K+ levels (mean difference between groups: −1.04 mEq/L; 95% CI, −1.37 to −0.71). Normokalemia in 73% of pts with SPS Trend toward ↑ electrolytic disturbances and GI side effects in SPS group. |

| Mistry et al., 2016 [35] | 118 | Patients who received SPS | Retrospective observational study | SPS 15, 30, and 60 g oral and 30 g Rectal | 12 h | ↓ K+ by 0.39, 0.69, 0.91, and 0.22 mEq/L following 15, 30, and 60 g oral doses and a 30 g rectal dose of SPS, respectively. 50% vs. 23% remained hyperkalemic in the 15 g group vs. 60 g group (p = 0.018) All patients in the rectal group remained hyperkalemic. No patient with postdose hypokalemia. |

| Sandal et al., 2012 [37] | 135 | Patients who received SPS | Retrospective observational study | 15 and 30 g o.d. | 24 h | ↓ K+: 16.7% (p < 0.001) within 24 h. No change in serum creatinine Patients with higher baseline K+ (≥5.6 mEq/L) better reduced K+ (>4%) than those with baseline K+ < 5.6 mEq/L (p = 0.32). No significant difference between 15 g and 30 g. 13 deaths, of which one due to ischemic colitis |

| Kessler et al., 2011 [36] | 122 | Patients with K+ >5.1 mEq/L. | Retrospective observational study | 15, 30, 45, and 60 g o.d. | N/A | ↓ K+:

|

| Chernin et al., 2012 [38] | 14 | CKD and heart disease on RAAS-I treatment after at least 1 episode of K+ ≥ 6.0 mEq/L | Prospective, longitudinal study | 15 g o.d. | 14.5 months | None developed colonic necrosis or life-threatening events attributed to SPS use. Mild hypokalemia in 2 patients No further episodes of hyperkalemia were recorded |

| Georgianos et al., 2017 [39] | 26 | Outpatients with stages 3–4 CKD | Retrospective observational study | 15 g o.d. | 15.4 months | ↓ K+: from 5.9 ± 0.4 to 4.8 ± 0.5 mEq/L (p < 0.001) Slight ↑ Na+: 139.5 ± 2.9 vs. 141.2 ± 2.4 mEq/L (p = 0.006). ~Ca2+ and phosphate No episode of colonic necrosis or other serious adverse events 1 patient had gastrointestinal intolerance. |

4.2. Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate (SZC)

4.3. Patiromer

| Study | N. of pts | Type of pts | Design | Approach | Follow-Up | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weir et al., 2015 [55] OPAL HK trial | 237 | CKD, on RAASi, serum K+ 5.1–6.5 mEq/L | RCT | Patiromer (initial dose 4.2 g or 8.4 g b.i.d.) for 4 weeks (initial treatment phase). Those who reached serum K+ 3.8–5.1 mEq/L randomized to continue patiromer or switch to placebo. | 12 weeks | At week 4: 76% pts reached serum K+ 3.8–5.1 mEq/L. Recurrence of hyperkalemia in the next 8 weeks (serum K+ ≥ 5.5 mEq/L) occurred in 15% pts on patiromer.Adverse effects: mild-to-moderate constipation (11% pts); hypokalemia (3% pts). |

| Bakris et al., 2015 [56] AMETHYST-DN trial | 306 | Pts type 2 DM, eGFR 15 to <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, serum K+ level > 5.0 mEq/L, RAASi | RCT | Stratified by baseline serum K+ into mild or moderate HK groups and received 1 of 3 randomized starting doses of patiromer (4.2 g b.i.d., 8.4 b.i.d., or 12.6 g b.i.d. (mild HK) or 8.4 g b.i.d., 12.6 g b.i.d., or 16.8 g b.i.d. (moderate HK)). | 52 weeks | Mild group, reduction in K+:

|

| Pitt et al., 2011 [57] PEARL HF trial | 105 | HF pts, history hyperkalaemia resulting in discontinuation of a RAASi and/or beta-adrenergic blocking agent or eGFR < 60 mL/min | RCT | 30 g o.d. RLY5016 or placebo for 4 weeks. Spironolactone, initiated at 25 mg o.d., increased to 50 mg o.d. on Day 15 if K+ was ≤5.1 mEq/L. | 4 weeks | RLY5016 significantly lowered serum K+ levels: difference between groups −0.45 mEq/L (p < 0.001) Lower incidence HK (7.3% RLY5016 vs. 24.5% placebo, p = 0.015) Higher proportion pts on spironolactone 50 mg o.d.: 91% RLY5016 vs. 74% placebo, p = 0.019. In CKD: difference in K+ between groups: −0.52 mEq/L (p = 0.031) Incidence HK: 6.7% RLY5016 vs. 38.5% placebo (p = 0.041). Adverse events: mainly mild or moderate GI. Hypokalaemia in 6% of RLY5016 pts vs. 0% of placebo pts. |

| Pitt et al., 2018 [58] AMETHYST-DN trial subanalysis | 105 | Pts type 2 DM, CKD, and HK [K+] > 5.0–5.5 mEq/L (mild) or >5.5–<6.0 mEq/L (moderate)], with or without HF, on RAASi | RCT | Stratified by baseline serum K+ into mild or moderate HK groups and received 1 of 3 randomized starting doses of patiromer (4.2 g b.i.d., 8.4 b.i.d., or 12.6 g b.i.d. (mild HK0 or 8.4 g b.i.d., 12.6 g b.i.d., or 16.8 g b.i.d. (moderate HK)). | 52 weeks | In HF patients, mean serum K+ decreased by Day 3 through Week 52. At Week 4:

|

| Zhuo et al., 2022 [61] | 3965 | New-user cohort study non-dialysis adults who initiated SZC or patiromer | Retrospective observational study | Comparing SZC vs. patiromer in HHF occurrence | 150 days | SZC group: 88 cases of HHF (incidence: 35.8 per 100 person-years) Patiromer group: 245 cases of HHF (incidence: 25.1 per 100 person-years). Rate HHF higher in SZC than patiromer initiators (HR: 1.22, 95% CI 0.95–1.56), but not statistically significant. |

| Kovesdy et al., 2019 [62] | 10126 | HD patients who had received patiromer, SPS, or laboratory evidence of hyperkalemia (NoKb cohort) | Retrospective observational study | 527 (patiromer) 852 (SPS) 8747 (NoKb) HD patients. | 141 days | Patiromer initiators had multiple prior HK (OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.8–3.7). 61% started with patiromer 8.4 g o.d. Reductions in K+: −0.5 mEq/L |

| Kovesdy et al., 2020 [63] | 288 | Veterans with HK (K+ ≥ 5.1 mEq/L) | Retrospective observational study | Patiromer initiators | 6 months | K+ reductions post-patiromer initiation: −1.0 mEq/L- At 3–6 months: K+ < 5.1 mEq/L: 71% of pts K+ < 5.5 mEq/L: 95% of pts RAASi continued in >80–90% of patiromer-treated patients. |

| Piña et al., 2020 [64] | 653 | HF and HK | Meta-analysis RCTs | Starting doses of patiromer ranged from 8.4 to 33.6 g o.d. | 4 weeks | Serum K+ decreased to <5.0 mEq/L within 1 week, nadir after 3 weeks in both HF and non-HF subgroups (4.59 mEq/L and 4.64 mEq/L, respectively). At 4 weeks: serum K+ difference from baselines: −0.79 ± 0.06 mEq/L in HF pts and −0.75 ± 0.02 mEq/L in non-HF pts. Adverse event in 31% HF pts and 37% non-HF pts: constipation (HF pts: 7%, non-HF pts: 5%) and diarrhea (HF pts: 2%, non-HF pts: 4%). |

5. Current Indication and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Savarese, G.; Lund, L.H. Global Public Health Burden of Heart Failure. Card. Fail. Rev. 2017, 3, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarese, G.; Becher, P.M.; Lund, L.H.; Seferovic, P.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Coats, A. Global Burden of Heart Failure: A Comprehensive and Updated Review of Epidemiology. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022; Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 4–131. [Google Scholar]

- Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) Study Investigators. Effects of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus: Results of the HOPE study and MICRO-HOPE substudy. Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. Lancet 2000, 355, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, S.; Pitt, B.; Davis, C.E.; Hood, W.B.; Cohn, J.N. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 325, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Desai, A.S.; Swedberg, K.; McMurray, J.J.; Granger, C.B.; Yusuf, S.; Young, J.B.; Dunlap, M.E.; Solomon, S.D.; Hainer, J.W.; Olofsson, B.; et al. CHARM Program Investigators. Incidence and predictors of hyperkalemia in patients with heart failure: An analysis of the CHARM Program. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 50, 1959–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lewis, E.J.; Hunsicker, L.G.; Clarke, W.R.; Berl, T.; Pohl, M.A.; Lewis, J.B.; Ritz, E.; Atkins, R.C.; Rohde, R.; Raz, I.; et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brenner, B.M.; Cooper, M.E.; de Zeeuw, D.; Keane, W.F.; Mitch, W.E.; Parving, H.H.; Remuzzi, G.; Snapinn, S.M.; Zhang, Z.; Shahinfar, S.; et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pitt, B.; Zannad, F.; Remme, W.J.; Cody, R.; Castaigne, A.; Perez, A.; Palensky, J.; Wittes, J.; Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zannad, F.; McMurray, J.J.; Krum, H.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Swedberg, K.; Shi, H.; Vincent, J.; Pocock, S.J.; Pitt, B.; EMPHASIS-HF Study Group. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McMurray, J.J.; Packer, M.; Desai, A.S.; Gong, J.; Lefkowitz, M.P.; Rizkala, A.R.; Rouleau, J.L.; Shi, V.C.; Solomon, S.D.; Swedberg, K.; et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 993–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, S.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Anand, I.S.; Ge, J.; Lam, C.S.P.; Maggioni, A.P.; Martinez, F.; Packer, M.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Pieske, B.; et al. Angiotensin-Neprilysin Inhibition in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1609–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Burnett, H.; Earley, A.; Voors, A.A.; Senni, M.; McMurray, J.J.; Deschaseaux, C.; Cope, S. Thirty Years of Evidence on the Efficacy of Drug Treatments for Chronic Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction: A Network Meta-Analysis. Circ. Heart Fail. 2017, 10, e003529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromp, J.; Ouwerkerk, W.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Hillege, H.L.; Richards, A.M.; van der Meer, P.; Anand, I.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Voors, A.A. A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Pharmacological Treatment of Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2022, 10, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raebel, M.A. Hyperkalemia associated with use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2012, 30, e156–e166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenlee, M.; Wingo, C.S.; McDonough, A.A.; Youn, J.H.; Kone, B.C. Narrative review: Evolving concepts in potassium homeostasis and hypokalemia. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosano, G.M.C.; Tamargo, J.; Kjeldsen, K.P.; Lainscak, M.; Agewall, S.; Anker, S.D.; Ceconi, C.; Coats, A.J.S.; Drexel, H.; Filippatos, G.; et al. Expert consensus document on the management of hyperkalaemia in patients with cardiovascular disease treated with renin angiotensin aldosterone system inhibitors: Coordinated by the Working Group on Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2018, 4, 180–188. [Google Scholar]

- Tromp, J.; van der Meer, P. Hyperkalaemia: Aetiology, epidemiology, and clinical significance. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 2019, 21, A6–A11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Betts, K.A.; Woolley, J.M.; Mu, F.; McDonald, E.; Tang, W.; Wu, E.Q. The prevalence of hyperkalemia in the United States. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2018, 34, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, F.; Betts, K.A.; Woolley, J.M.; Dua, A.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, J.; Wu, E.Q. Prevalence and economic burden of hyperkalemia in the United States Medicare population. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2020, 36, 1333–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, R.W.; Nicolaisen, S.K.; Hasvold, P.; Garcia-Sanchez, R.; Pedersen, L.; Adelborg, K.; Egfjord, M.; Egstrup, K.; Sørensen, H.T. Elevated Potassium Levels in Patients With Congestive Heart Failure: Occurrence, Risk Factors, and Clinical Outcomes: A Danish Population-Based Cohort Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e008912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Savarese, G.; Xu, H.; Trevisan, M.; Dahlström, U.; Rossignol, P.; Pitt, B.; Lund, L.H.; Carrero, J.J. Incidence, Predictors, and Outcome Associations of Dyskalemia in Heart Failure With Preserved, Mid-Range, and Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2019, 7, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez, J.; Bayés-Genís, A.; Zannad, F.; Rossignol, P.; Núñez, E.; Bodí, V.; Miñana, G.; Santas, E.; Chorro, F.J.; Mollar, A.; et al. Long-Term Potassium Monitoring and Dynamics in Heart Failure and Risk of Mortality. Circulation 2018, 137, 1320–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoss, S.; Elizur, Y.; Luria, D.; Keren, A.; Lotan, C.; Gotsman, I. Serum Potassium Levels and Outcome in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 2016, 118, 1868–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Barge-Caballero, E.; Segovia-Cubero, J.; González-Costello, J.; López-Fernández, S.; García-Pinilla, J.M.; Almenar-Bonet, L.; de Juan-Bagudá, J.; Roig-Minguell, E.; Bayés-Genís, A.; et al. Hyperkalemia in heart failure patients in Spain and its impact on guidelines and recommendations: ESC-EORP-HFA Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2020, 73, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilstrap, L.G.; Fonarow, G.C.; Desai, A.S.; Liang, L.; Matsouaka, R.; DeVore, A.D.; Smith, E.E.; Heidenreich, P.; Hernandez, A.F.; Yancy, C.W.; et al. Initiation, Continuation, or Withdrawal of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors/Angiotensin Receptor Blockers and Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e004675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lisi, F.; Parisi, G.; Gioia, M.I.; Amato, L.; Bellino, M.C.; Grande, D.; Massari, F.; Caldarola, P.; Ciccone, M.M.; Iacoviello, M. Mineralcorticoid Receptor Antagonist Withdrawal for Hyperkalemia and Mortality in Patients with Heart Failure. Cardiorenal Med. 2020, 10, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, B.F. Managing hyperkalemia caused by inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palmer, B.F.; Clegg, D.J. Physiology and pathophysiology of potassium homeostasis. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2016, 40, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamada, S.; Inaba, M. Potassium Metabolism and Management in Patients with CKD. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/011287s023lbl.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-recommends-separating-dosing-potassium-lowering-drug-sodium (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Batterink, J.; Lin, J.; Au-Yeung, S.H.; Cessford, T. Effectiveness of Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate for Short-Term Treatment of Hyperkalemia. Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2015, 68, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lepage, L.; Dufour, A.C.; Doiron, J.; Handfield, K.; Desforges, K.; Bell, R.; Vallée, M.; Savoie, M.; Perreault, S.; Laurin, L.P.; et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate for the Treatment of Mild Hyperkalemia in CKD. Clin. J. Am. SocNephrol. 2015, 10, 2136–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, M.; Shea, A.; Giguère, P.; Nguyen, M.L. Evaluation of Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate Dosing Strategies in the Inpatient Management of Hyperkalemia. Ann. Pharmacother. 2016, 50, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, C.; Ng, J.; Valdez, K.; Xie, H.; Geiger, B. The use of sodium polystyrene sulfonate in the inpatient management of hyperkalemia. J. Hosp. Med. 2011, 6, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandal, S.; Karachiwala, H.; Noviasky, J.; Wang, D.; Elliott, W.C.; Lehmann, D.F. To bind or to let loose: Effectiveness of sodium polystyrene sulfonate in decreasing serum potassium. Int. J. Nephrol. 2012, 2012, 940320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernin, G.; Gal-Oz, A.; Ben-Assa, E.; Schwartz, I.F.; Weinstein, T.; Schwartz, D.; Silverberg, D.S. Secondary prevention of hyperkalemia with sodium polystyrene sulfonate in cardiac and kidney patients on renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition therapy. Clin. Cardiol. 2012, 35, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgianos, P.I.; Liampas, I.; Kyriakou, A.; Vaios, V.; Raptis, V.; Savvidis, N.; Sioulis, A.; Liakopoulos, V.; Balaskas, E.V.; Zebekakis, P.E. Evaluation of the tolerability and efficacy of sodium polystyrene sulfonate for long-term management of hyperkalemia in patients with chronic kidney disease. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2017, 49, 2217–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holleck, J.L.; Roberts, A.E.; Marhoffer, E.A.; Grimshaw, A.A.; Gunderson, C.G. Risk of Intestinal Necrosis With Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Hosp. Med. 2021, 16, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavros, F.; Yang, A.; Leon, A.; Nuttall, M.; Rasmussen, H.S. Characterization of structure and function of ZS-9, a K+ selective ion trap. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packham, D.K.; Rasmussen, H.S.; Lavin, P.T.; El-Shahawy, M.A.; Roger, S.D.; Block, G.; Qunibi, W.; Pergola, P.; Singh, B. Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate in hyperkalemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kosiborod, M.; Rasmussen, H.S.; Lavin, P.; Qunibi, W.Y.; Spinowitz, B.; Packham, D.; Roger, S.D.; Yang, A.; Lerma, E.; Singh, B. Effect of sodium zirconium cyclosilicate on potassium lowering for 28 days among outpatients with hyperkalemia: The HARMONIZE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014, 312, 2223–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannad, F.; Hsu, B.G.; Maeda, Y.; Shin, S.K.; Vishneva, E.M.; Rensfeldt, M.; Eklund, S.; Zhao, J. Efficacy and safety of sodium zirconium cyclosilicate for hyperkalaemia: The randomized, placebo-controlled HARMONIZE-Global study. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roger, S.D.; Spinowitz, B.S.; Lerma, E.V.; Singh, B.; Packham, D.K.; Al-Shurbaji, A.; Kosiborod, M. Efficacy and Safety of Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate for Treatment of Hyperkalemia: An 11-Month Open-Label Extension of HARMONIZE. Am. J. Nephrol. 2019, 50, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roger, S.D.; Lavin, P.T.; Lerma, E.V.; McCullough, P.A.; Butler, J.; Spinowitz, B.S.; von Haehling, S.; Kosiborod, M.; Zhao, J.; Fishbane, S.; et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of sodium zirconium cyclosilicate for hyperkalaemia in patients with mild/moderate versus severe/end-stage chronic kidney disease: Comparative results from an open-label, Phase 3 study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbane, S.; Ford, M.; Fukagawa, M.; McCafferty, K.; Rastogi, A.; Spinowitz, B.; Staroselskiy, K.; Vishnevskiy, K.; Lisovskaja, V.; Al-Shurbaji, A.; et al. A Phase 3b, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate for Reducing the Incidence of Predialysis Hyperkalemia. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 30, 1723–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anker, S.D.; Kosiborod, M.; Zannad, F.; Piña, I.L.; McCullough, P.A.; Filippatos, G.; van der Meer, P.; Ponikowski, P.; Rasmussen, H.S.; Lavin, P.T.; et al. Maintenance of serum potassium with sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS-9) in heart failure patients: Results from a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 1050–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, T.; Oshima, A.; Narang, N.; Kinugawa, K. Clinical Implications of Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate Therapy in Patients with Systolic Heart Failure and Hyperkalemia. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, D.; Ster, I.C.; Kaski, J.C.; Anderson, L.; Banerjee, D. The LIFT trial: Study protocol for a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial of K+-binder Lokelma for maximisation of RAAS inhibition in CKD patients with heart failure. BMC Nephrol. 2021, 22, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05004363 (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2015/205739Orig1s000TOC.cfm (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/veltassa-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Li, L.; Harrison, S.D.; Cope, M.J.; Park, C.; Lee, L.; Salaymeh, F.; Madsen, D.; Benton, W.W.; Berman, L.; Buysse, J. Mechanism of Action and Pharmacology of Patiromer, a Nonabsorbed Cross-Linked Polymer That Lowers Serum Potassium Concentration in Patients With Hyperkalemia. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 21, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, M.R.; Bakris, G.L.; Bushinsky, D.A.; Mayo, M.R.; Garza, D.; Stasiv, Y.; Wittes, J.; Christ-Schmidt, H.; Berman, L.; Pitt, B.; et al. Patiromer in patients with kidney disease and hyperkalemia receiving RAAS inhibitors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakris, G.L.; Pitt, B.; Weir, M.R.; Freeman, M.W.; Mayo, M.R.; Garza, D.; Stasiv, Y.; Zawadzki, R.; Berman, L.; Bushinsky, D.A.; et al. Effect of Patiromer on Serum Potassium Level in Patients With Hyperkalemia and Diabetic Kidney Disease: The AMETHYST-DN Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2015, 314, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, B.; Anker, S.D.; Bushinsky, D.A.; Kitzman, D.W.; Zannad, F.; Huang, I.Z.; PEARL-HF Investigators. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of RLY5016, a polymeric potassium binder, in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with chronic heart failure (the PEARL-HF) trial. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pitt, B.; Bakris, G.L.; Weir, M.R.; Freeman, M.W.; Lainscak, M.; Mayo, M.R.; Garza, D.; Zawadzki, R.; Berman, L.; Bushinsky, D.A. Long-term effects of patiromer for hyperkalaemia treatment in patients with mild heart failure and diabetic nephropathy on angiotensin-converting enzymes/angiotensin receptor blockers: Results from AMETHYST-DN. ESC Heart Fail. 2018, 5, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, J.; Anker, S.D.; Siddiqi, T.J.; Coats, A.J.S.; Dorigotti, F.; Filippatos, G.; Friede, T.; Göhring, U.M.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Lund, L.H.; et al. Patiromer for the management of hyperkalaemia in patients receiving renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors for heart failure: Design and rationale of the DIAMOND trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piña, I.L.; Yuan, J.; Ackourey, G.; Ventura, H. Effect of patiromer on serum potassium in hyperkalemic patients with heart failure: Pooled analysis of 3 randomized trials. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 63, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, M.; Kim, S.C.; Patorno, E.; Paik, J.M. Risk of Hospitalization for Heart Failure in Patients With Hyperkalemia Treated With Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate vs. Patiromer. J. Card. Fail. 2022; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovesdy, C.P.; Rowan, C.G.; Conrad, A.; Spiegel, D.M.; Fogli, J.; Oestreicher, N.; Connaire, J.J.; Winkelmayer, W.C. Real-World Evaluation of Patiromer for the Treatment of Hyperkalemia in Hemodialysis Patients. Kidney Int. Rep. 2018, 4, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kovesdy, C.P.; Gosmanova, E.O.; Woods, S.D.; Fogli, J.J.; Rowan, C.G.; Hansen, J.L.; Sauer, B.C. Real-world management of hyperkalemia with patiromer among United States Veterans. Postgrad. Med. 2020, 132, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, R.; Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhao, N.; Cheng, F.; Long, L.; Jia, J.; Lin, S. Effects and Safety of a Novel Oral Potassium-Lowering Drug-Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate for the Treatment of Hyperkalemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2021, 35, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/lokelma-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Das, S.; Dey, J.K.; Sen, S.; Mukherjee, R. Efficacy and Safety of Patiromer in Hyperkalemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pharm. Pract. 2018, 31, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rafique, Z.; Liu, M.; Staggers, K.A.; Minard, C.G.; Peacock, W.F. Patiromer for Treatment of Hyperkalemia in the Emergency Department: A Pilot Study. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020, 27, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Palo, K.E.; Sinnett, M.J.; Goriacko, P. Assessment of Patiromer Monotherapy for Hyperkalemia in an Acute Care Setting. JAMA Netw. Open. 2022, 5, e2145236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.T.; Kataria, V.K.; Sam, T.R.; Hooper, K.; Mehta, A.N. Comparison of Patiromer to Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate in Acute Hyperkalemia. Hosp. Pharm. 2022, 57, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peacock, W.F.; Rafique, Z.; Vishnevskiy, K.; Michelson, E.; Vishneva, E.; Zvereva, T.; Nahra, R.; Li, D.; Miller, J. Emergency Potassium Normalization Treatment Including Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate: A Phase II, Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study (ENERGIZE). Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020, 27, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate | Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate | Patiromer Sorbitex Calcium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical formula | [C8H8SO3−]n | (2Na·H2O·3H4SiO4·H4ZrO6)n | [(C3H3FO2)182·(C10H10)8·(C8H14)10]n [Ca91(C3H2FO2)182·(C10H10)8·(C8H14)10]n (calcium salt) |

| Chemical structure |  |  |  |

| Molecular weight | 184.21 U | 371.5 U | 901.10 |

| Administration | Oral or rectal administration | Oral administration | Oral administration |

| Dose | Oral: 15 g to 60 g 1 to 4 times daily. Rectal: 30 to 50 g every 6 h. | Starting: 10 g t.i.d. Maintenance: 5 g o.d. (eventually increase to 10 g o.d.) In hemodialysis:

| Starting dose is 8.4 g patiromer o.d. Daily dose may be increased to 16.8 g or maximum 25.2 g o.d. |

| Absorption | None | None | None |

| Excretion | Feces | Feces | Feces |

| Onset of Action | Within 2–24 h till 4 to 6 h Exchange capacity: ~33% or 1 mEq of K+ per 1 g of resin. Variation for competition to other cations (Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+) | Within 1–6 h, normokalemia in 24–48 h | Within 4–7 h, duration about 24 h |

| Pharmacodynamics | Cation exchange resin, Na+ ions partially released from polystyrene and replaced by K+ | Non-absorbed, non-polymer inorganic powder with a micropore structure that high selectively captures K+ in exchange for H+ and Na+ in the GI tract. | Non-absorbed, cation exchange polymer that contains a calcium-sorbitol complex. It binds K+ in the lumen of the GI tract. |

| Side effects | ↑ [Na+]; ↓ [Ca2+]; ↓ [K+]; ↓ [Mg2+] GI: Anorexia, constipation, diarrhea, fecal impaction, nausea, vomiting <1%, postmarketing, and/or case reports: Bezoar formation, GI hemorrhage, GI ulcer, intestinal necrosis, intestinal perforation, ischemic colitis | ↓ K+ Edema GI: anorexia, constipation, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting | ↓ Mg2+ GI disorders: constipation, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, flatulence, nausea, vomiting |

| Study | N. of pts | Type of pts | Design | Approach | Follow-Up | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Packham et al., 2015 [42] | 754 | Patients with K+ 5.0–6.5 mEq/L | RCT | Randomly assigned to 1.25 g, 2.5 g, 5 g, or 10 g of SZC or placebo t.i.d. for the initial 48 h (initial phase). Those in the SZC group who reached K+ 3.5–4.9 mEq/L at 48 h randomly assigned (1:1) to original SZC dose or placebo o.d. on days 3 to 14 (maintenance). | 14 days | At 48 h K+ decreased:

|

| Kosiborod et al., 2014 [43] HARMONIZE trial | 258 | Outpatients with K+ ≥ 5.1 mEq/L | rct | 10 g szc t.i.d. in the initial 48-h, Those achieving k+ 3.5–5.0 mEq/L randomized to szc 5 g, 10 g, or 15 g, or placebo o.d. for 28 days | 28 days | At 48h K+ decreased from 5.6 mEq/L to 4.5 mEq/L Normokalemia in 84% in 24 h; 98% in 48 h. Days 8–29 (vs. placebo):

|

| Zannad et al., 2020 [44] HARMONIZE GLOBAL | 262 | Outpatients with K+ ≥ 5.1 mEq/L | RCT | 10 g SZC t.i.d. in the initial 48 h, Those achieving K+ 3.5–5.0 mEq/L randomized to SZC 5 g, 10 g, or placebo o.d. for 28 days | 28 days | 92.9% reached normokalemia after 48 h; mean reduction in K+: −1.28 mEq/L vs. baseline (p < 0.001). Days 8–29, mean reduction K+:

|

| Roger et al., 2019 [45] HARMONIZE extension | 123 | HARMONIZE trial pts with K+ 3.5–6.2 mEq/L | RCT | SZC 5–10 g o.d. for ≤337 days | 337 days | K+ ≤ 5.1 mEq/L in 88.3% of pts after 337 days K+ ≤ 5.5 mEq/L in 100% of pts after 337 days |

| Roger et al., 2021 [46] | 751 | Outpatients with K+ ≥ 5.1 mEq/L and Stages 4 and 5 CKD versus those with Stages 1–3 CKD. | RCT | SZC 10 g t.i.d. for 24–72 h until K+ 3.5–5.0 mmol/L then SZC 5 g o.d. for ≤12 months Patients stratified by eGFR < 30 or ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 12 months | Percentage of pts with normokalemia:

|

| Fishbane et al., 2019 [47] DIALIZE trial | 196 | ESRD in 3-times weekly hemodialysis and predialysis hyperkalemia | RCT | Randomized to placebo or SZC 5 g o.d. (titrated till 15 g in relation to serum K+ level) on non-dialysis days. | 4 weeks | 41.2% reached normokalemia. Serious adverse events in 7% pts treated with SZC Few episodes of hypokalemia. |

| Anker et al., 2015 [48] HARMONIZE substudy | 94 | HF pts from HARMONIZE, with serum K+ ≥ 5.1 mEq/L, and including those receiving RAASi. | RCT | Open-label SZC for 48 h. Those who achieved K+ 3.5–5.0 mEq/L randomized to SZC 5, 10, or 15 g or placebo o.d. for 28 days. | 28 days | Despite RAASi doses being kept constant, serum K+ levels were:

|

| Imamura et al., 2021 [49] | 24 | HF pts with LVEF < 50% and hyperkalemia | Retrospective observational study | SZC 5–15 g o.d. | 3 months | ↓ serum K+ ↑ RAASi dose No adverse events |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scicchitano, P.; Iacoviello, M.; Massari, F.; De Palo, M.; Caldarola, P.; Mannarini, A.; Passantino, A.; Ciccone, M.M.; Magnesa, M. Optimizing Therapies in Heart Failure: The Role of Potassium Binders. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1721. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10071721

Scicchitano P, Iacoviello M, Massari F, De Palo M, Caldarola P, Mannarini A, Passantino A, Ciccone MM, Magnesa M. Optimizing Therapies in Heart Failure: The Role of Potassium Binders. Biomedicines. 2022; 10(7):1721. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10071721

Chicago/Turabian StyleScicchitano, Pietro, Massimo Iacoviello, Francesco Massari, Micaela De Palo, Pasquale Caldarola, Antonia Mannarini, Andrea Passantino, Marco Matteo Ciccone, and Michele Magnesa. 2022. "Optimizing Therapies in Heart Failure: The Role of Potassium Binders" Biomedicines 10, no. 7: 1721. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10071721

APA StyleScicchitano, P., Iacoviello, M., Massari, F., De Palo, M., Caldarola, P., Mannarini, A., Passantino, A., Ciccone, M. M., & Magnesa, M. (2022). Optimizing Therapies in Heart Failure: The Role of Potassium Binders. Biomedicines, 10(7), 1721. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10071721