Bleomycin Electrochemotherapy of Dermal Cylindroma as an Alternative Treatment in a Rare Adnexal Neoplasm: A Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

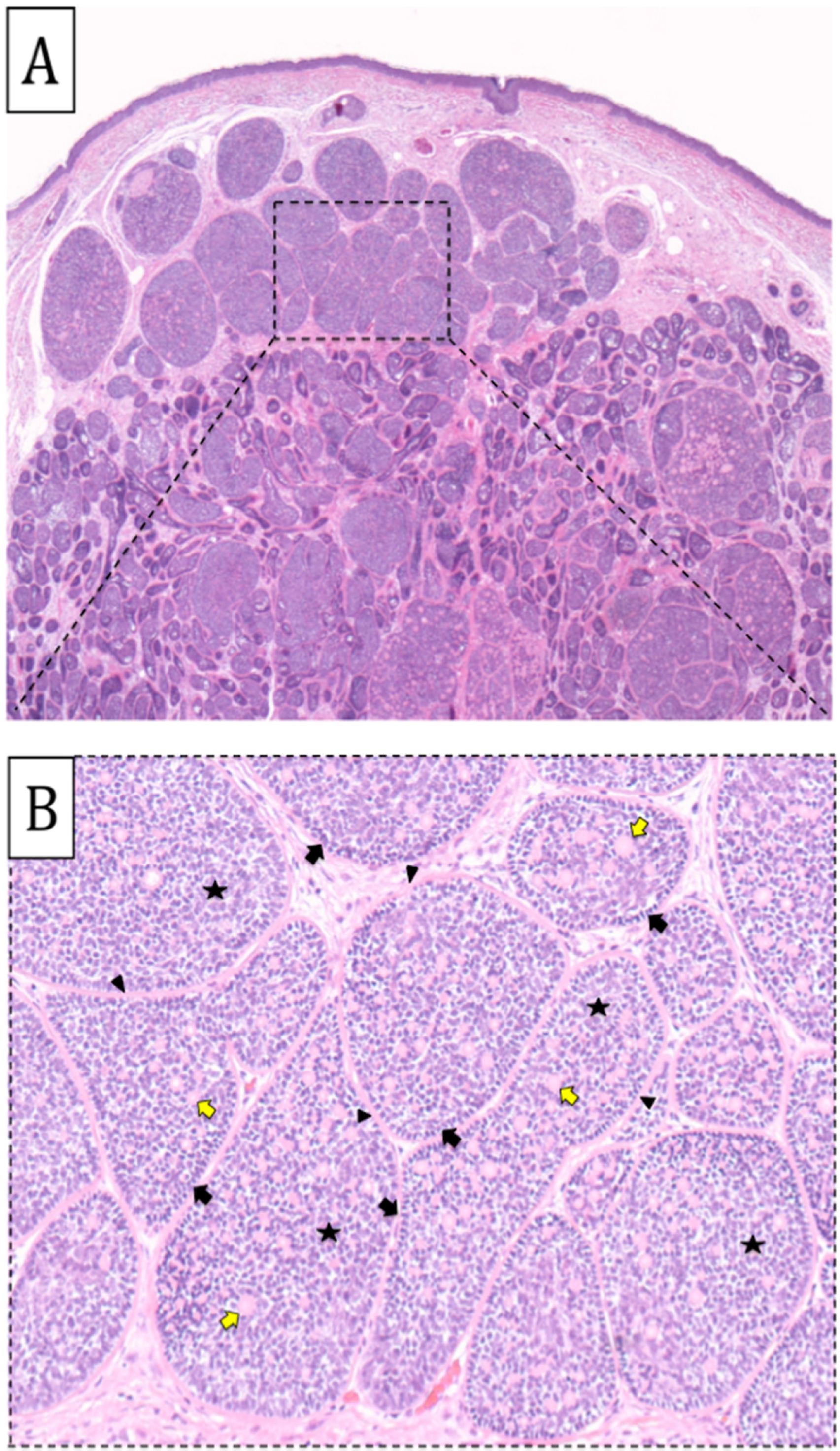

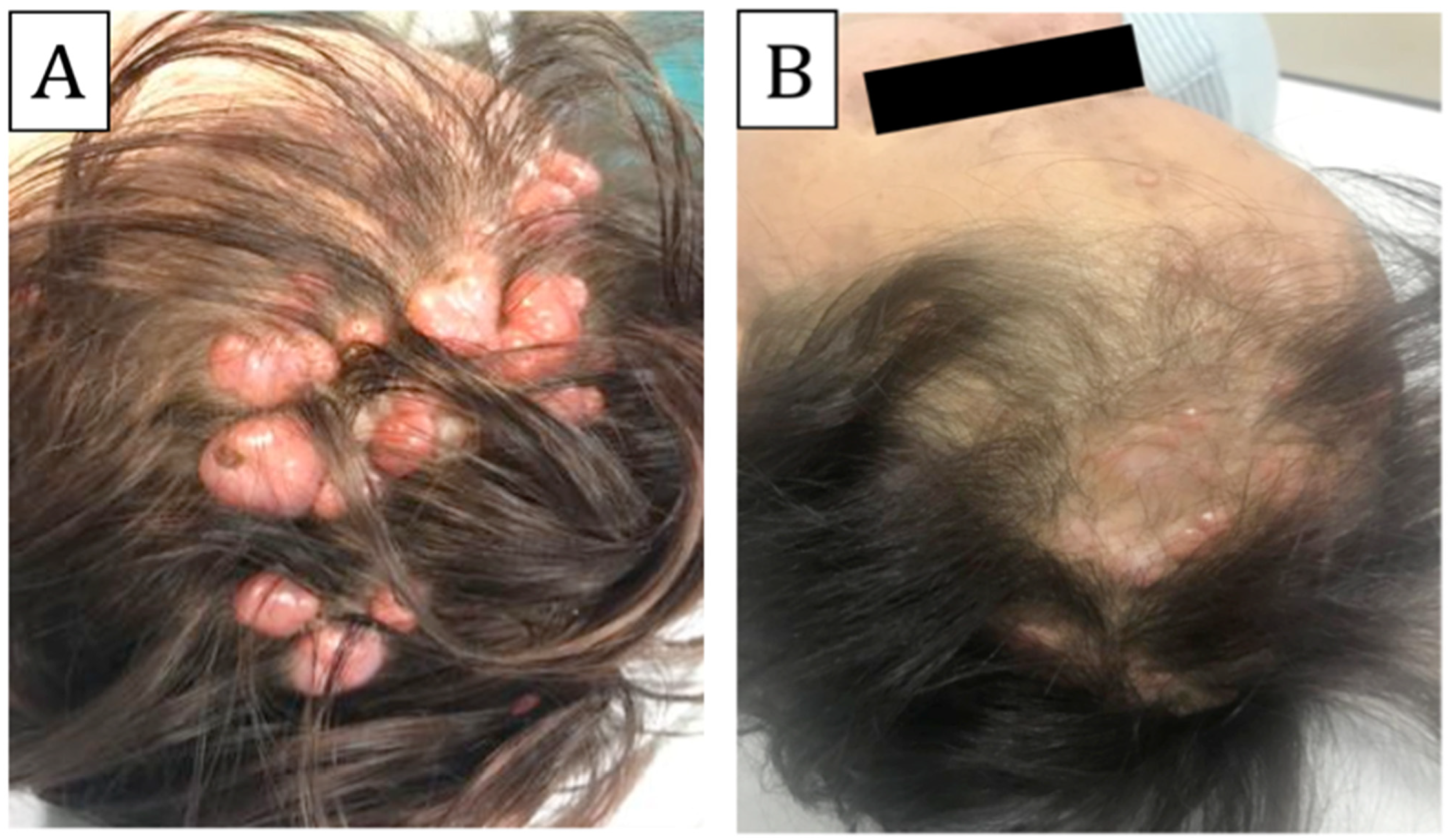

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gutiérrez, P.P.; Eggermann, T.; Höller, D.; Jugert, F.K.; Beermann, T.; Grußendorf-Conen, E.I.; Frank, J. Phenotype diversity in familial cylindromatosis: A frameshift mutation in the tumor suppressor gene CYLD underlies different tumors of skin appendages. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2002, 119, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, S.; Gill, M.; Lee, D.A.; Fisher, G.; Geronemus, R.G.; Vazquez, M.E.; Celebi, J.T. Mutations in the CYLD gene in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, familial cylindromatosis, and multiple familial trichoepithelioma: Lack of genotype-phenotype correlation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2005, 124, 919–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, N.; Ashworth, A. Inherited cylindromas: Lessons from a rare tumour. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, e460–e469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, A.; Hodgson, K.; Rajan, N. Understanding inherited cylindromas clinical implications of gene discovery. Dermatol. Clin. 2017, 35, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, N.; Trainer, A.H.; Burn, J.; Langtry, J.A. Familial cylindromatosis and brooke-spiegler syndrome: A review of current therapeutic approaches and the surgical challenges posed by two affected families. Dermatol. Surg. 2009, 35, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, U.; Fuhrmann, I.; Beyer, L.; Wiggermann, P. Electrochemotherapy as a new modality in interventional oncology: A review. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 17, 1533033818785329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, J.P.; Gerriets, V. Bleomycin; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht, S.M. Bleomycin: New perspectives on the mechanism of action. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastrup, F.A.; Vissing, M.; Gehl, J. Electrochemotherapy with intravenous bleomycin for patients with cutaneous malignancies, across tumour histology: A systematic review. Acta Oncol. 2022, 61, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, L.G.; Testori, A.; Curatolo, P.; Quaglino, P.; Mocellin, S.; Framarini, M.; Bonadies, A. Treatment efficacy with electrochemotherapy: A multi-institutional prospective observational study on 376 patients with superficial tumors. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 42, 1914–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clover AJ, P.; de Terlizzi, F.; Bertino, G.; Curatolo, P.; Odili, J.; Campana, L.G.; Gehl, J. Electrochemotherapy in the treatment of cutaneous malignancy: Outcomes and subgroup analysis from the cumulative results from the pan-European International Network for Sharing Practice in Electrochemotherapy database for 2482 lesions in 987 patients (2008–2019). Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 138, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fabrizio, T.; Cagiano, L.; De Terlizzi, F.; Grieco, M.P. Neoadjuvant treatment by ECT in cutaneous malignant neoplastic lesions. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2020, 73, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarm, T.; Cemazar, M.; Miklavcic, D.; Sersa, G. Antivascular effects of electrochemotherapy: Implications in treatment of bleeding metastases. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2010, 10, 729–746. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J.; Sersa, G.; Matthiessen, L.W.; Muir, T.; Soden, D.; Occhini, A.; Mir, L.M. Updated standard operating procedures for electrochemotherapy of cutaneous tumours and skin metastases. Acta Oncol. 2018, 57, 874–882. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas-Truyols, S.; Lloret-Ruiz, C.; Millán-Parrilla, F.; Gimeno-Carpio, E. A Simple and Effective Method for Treating Cylindromas in Brooke-Spiegler Syndrome. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017, 108, 692–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parren, L.J.; Ferdinandus, P.; van der Hulst, R.; Frank, J.; Tuinder, S. A novel therapeutic strategy for turban tumor: Scalp excision and combined reconstruction with artificial dermis and split skin graft. Int. J. Dermatol. 2014, 53, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brass, D.; Rajan, N.; Langtry, J. Enucleation of Cylindromas in Brooke-Spiegler Syndrome: A Novel Surgical Technique. Dermatol. Surg. 2014, 40, 1438–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamar, R.A.; Stengel, F.; Saadi, M.E.; Kien, M.C.; Della Giovana, P.; Cabrera, H.; Chouela, E.N. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome—Report of four families: Treatment with CO2 laser. Int. J. Dermatol. 2007, 46, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertino, G.; Sersa, G.; De Terlizzi, F.; Occhini, A.; Plaschke, C.C.; Groselj, A.; Benazzo, M. European Research on Electrochemotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer (EURECA) project: Results of the treatment of skin cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 63, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kis, E.G.; Baltás, E.; Ócsai, H.; Vass, A.; Németh, I.B.; Varga, E.; Tóth-Molnár, E. Electrochemotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced or recurrent eyelid-periocular basal cell carcinomas. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonadies, A.; Bertozzi, E.; Cristiani, R.; Govoni, F.A.; Migliano, E. Electrochemotherapy in Skin Malignancies of Head and Neck Cancer Patients: Clinical Efficacy and Aesthetic Benefits. Acta Dermato-Venereol. 2019, 99, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaglino, P.; Mortera, C.; Osella-Abate, S.; Barberis, M.; Illengo, M.; Rissone, M.; Bernengo, M.G. Electrochemotherapy with intravenous bleomycin in the local treatment of skin melanoma metastases. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2008, 15, 2215–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bonadies, A.; Iorio, A.; Silipo, V.; Cota, C.; Govoni, F.A.; Battista, M.; Pallara, T.; Migliano, E. Bleomycin Electrochemotherapy of Dermal Cylindroma as an Alternative Treatment in a Rare Adnexal Neoplasm: A Case Report and Literature Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2667. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11102667

Bonadies A, Iorio A, Silipo V, Cota C, Govoni FA, Battista M, Pallara T, Migliano E. Bleomycin Electrochemotherapy of Dermal Cylindroma as an Alternative Treatment in a Rare Adnexal Neoplasm: A Case Report and Literature Review. Biomedicines. 2023; 11(10):2667. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11102667

Chicago/Turabian StyleBonadies, Antonio, Alessandra Iorio, Vitaliano Silipo, Carlo Cota, Flavio Andrea Govoni, Michela Battista, Tiziano Pallara, and Emilia Migliano. 2023. "Bleomycin Electrochemotherapy of Dermal Cylindroma as an Alternative Treatment in a Rare Adnexal Neoplasm: A Case Report and Literature Review" Biomedicines 11, no. 10: 2667. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11102667

APA StyleBonadies, A., Iorio, A., Silipo, V., Cota, C., Govoni, F. A., Battista, M., Pallara, T., & Migliano, E. (2023). Bleomycin Electrochemotherapy of Dermal Cylindroma as an Alternative Treatment in a Rare Adnexal Neoplasm: A Case Report and Literature Review. Biomedicines, 11(10), 2667. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11102667