Management of Foot Ulcers and Chronic Wounds with Amniotic Membrane in Comorbid Patients: A Successful Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Donor Selection and Informed Consent

2.2. Amniotic Membrane Processing

2.3. Procedure for AM Application in Wounds

2.4. Advanced Therapy Approval and Ethical Aspects

2.5. Patient Selection and Monitoring

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient’s Profile and Outcomes

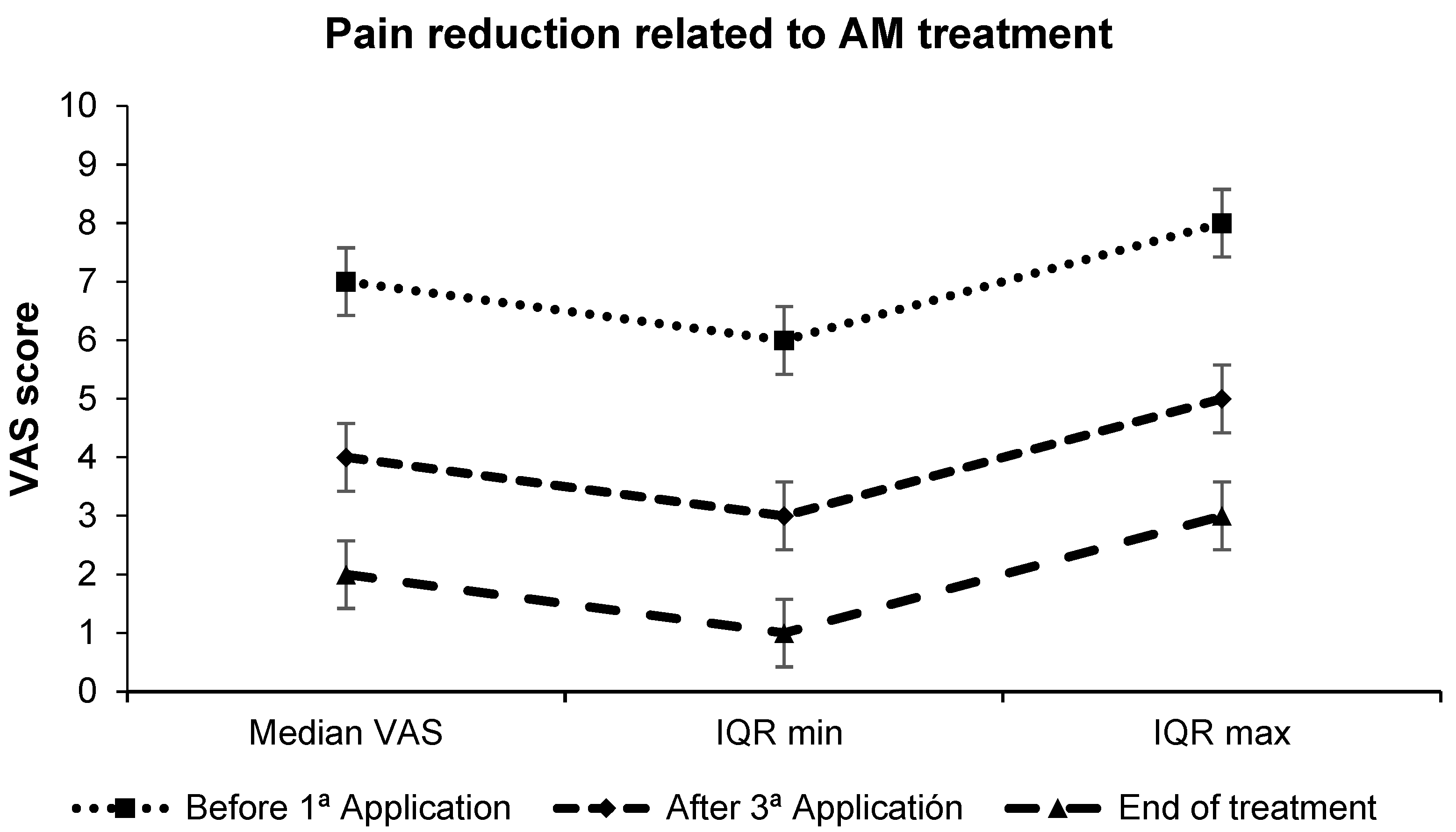

3.2. Pain Perception

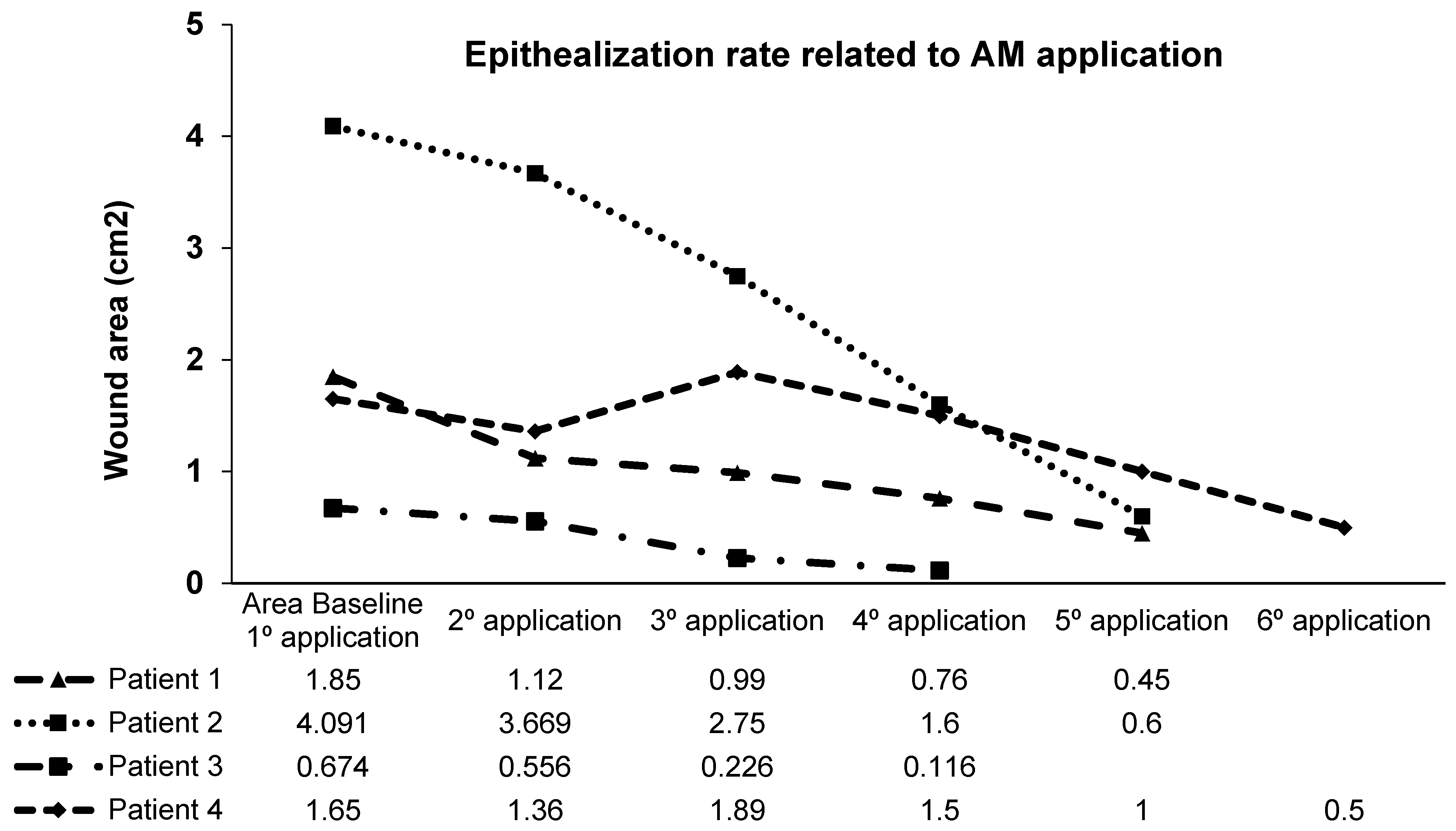

3.3. Wound Epithelialization

3.4. Microbiology

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Glossary

| IQR | Interquartile range, a measure of statistical dispersion. It is calculated as the difference between the third quartile and the first quartile. RQ = Q3 − Q1. |

| VAS | Visual analogue scale. The visual analog scale is a psychometric response scale that can be used in questionnaires. It is an instrument for measuring subjective characteristics or attitudes. It is numbered from 1 to 10, with 1 being the least pain and 10 being the maximum pain felt. |

| SOP | standard work protocol. |

| AEMPS | Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices |

| CPU | Cell production unit |

References

- Labib, A.; Winters, R. Complex Wound Management. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Augustin, M.; Conde Montero, E.; Zander, N.; Baade, K.; Herberger, K.; Debus, E.S.; Diener, H.; Neubert, T.; Blome, C. Validity and Feasibility of the Wound-QoL Questionnaire on Health-Related Quality of Life in Chronic Wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2017, 25, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herberger, K.; Rustenbach, S.J.; Haartje, O.; Blome, C.; Franzke, N.; Schäfer, I.; Radtke, M.; Augustin, M. Quality of Life and Satisfaction of Patients with Leg Ulcers—Results of a Community-Based Study. Vasa 2011, 40, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franks, P.J.; Moffatt, C.J.; Connolly, M.; Bosanquet, N.; Oldroyd, M.; Greenhalgh, R.M.; McCollum, C.N. Community Leg Ulcer Clinics: Effect on Quality of Life. Phlebology 1994, 9, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, P.J.; Moffatt, C.J.; Doherty, D.C.; Smithdale, R.; Martin, R. Longer-Term Changes in Quality of Life in Chronic Leg Ulceration. Wound Repair Regen. 2006, 14, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindholm, C.; Bjellerup, M.; Christensen, O.B.; Zederfeldt, B. Quality of Life in Chronic Leg Ulcer Patients. An Assessment According to the Nottingham Health Profile. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 1993, 73, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, T.; Stanton, B.; Provan, A.; Lew, R. Lew. A Study of the Impact of Leg Ulcers on Quality of Life: Financial, Social, and Psychologic Implications. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1994, 31, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcaraz, A.; Mrowiec, A.; Insausti, C.L.; Bernabé-García, Á.; García-Vizcaíno, E.M.; López-Martínez, M.C.; Monfort, A.; Izeta, A.; Moraleda, J.M.; Castellanos, G.; et al. Amniotic Membrane Modifies the Genetic Program Induced by TGFβ, Stimulating Keratinocyte Proliferation and Migration in Chronic Wounds. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135324, Erratum in PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parolini, O.; Alviano, F.; Bagnara, G.P.; Bilic, G.; Bühring, H.J.; Evangelista, M.; Hennerbichler, S.; Liu, B.; Magatti, M.; Mao, N.; et al. Concise Review: Isolation and Characterization of Cells from Human Term Placenta: Outcome of the First International Workshop on Placenta Derived Stem Cells. Stem Cells 2008, 26, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RuizRuiz-Cañada, C.; Bernabé-García, Á.; Liarte, S.; Rodríguez-Valiente, M.; Nicolás, F.J. Chronic Wound Healing by Amniotic Membrane: TGF-β and EGF Signaling Modulation in Re-Epithelialization. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 689328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hasegawa, T.; Mizoguchi, M.; Haruna, K.; Mizuno, Y.; Muramatsu, S.; Suga, Y.; Ogawa, H.; Ikeda, S. Amnia for Intractable Skin Ulcers with Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa: Report of Three Cases. J. Dermatol. 2007, 34, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mermet, I.; Pottier, N.; Sainthillier, J.M.; Malugani, C.; Cairey-Remonnay, S.; Maddens, S.; Riethmuller, D.; Tiberghien, P.; Humbert, P.; Aubin, F. Use of Amniotic Membrane Transplantation in the Treatment of Venous Leg Ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2007, 15, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskandarlou, M.; Azimi, M.; Rabiee, S.; Rabiee, M.A.S. The Healing Effect of Amniotic Membrane in Burn Patients. World J. Plast. Surg. 2016, 5, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Valiente, M.R.; Nicolás, F.J.; García-Hernández, A.M.; Fuente Mora, C.; Blanquer, M.; Alcaraz, P.J.; Almansa, S.; Merino, G.R.; Lucas, M.D.L.; Algueró, M.C.; et al. Cryopreserved Amniotic Membrane in the Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Case Series. J. Wound Care 2018, 27, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liarte, S.; Bernabé-García, Á.; Rodríguez-Valiente, M.; Moraleda, J.M.; Castellanos, G.; Nicolás, F.J. Amniotic Membrane Restores Chronic Wound Features to Normal in a Keratinocyte TGF-β-Chronified Cell Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Garcia de Insausti, C.L. Aislamiento y Caracterización de las celulas Madre de la Membrana Amniótica: Una nueva fuente para la terapia celular e Inmuno-Modulación. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Murcia, Murcia, Spain, 2012. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10201/27479 (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- Rasband; Wayne, S. ImageJ. U.S. National Institutes of Health, 1997–2024. Available online: https://imagej.net/ij/download.html (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Insausti, C.L.; Alcaraz, A.; García-Vizcaíno, E.M.; Mrowiec, A.; López-Martínez, M.C.; Blanquer, M.; Piñero, A.; Majado, M.J.; Moraleda, J.M.; Castellanos, G.; et al. Amniotic membrane induces epithelialization in massive posttraumatic wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2010, 18, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gindraux, F.; Hofmann, N.; Agudo-Barriuso, M.; Antica, M.; Couto, P.S.; Dubus, M.; Forostyak, S.; Girandon, L.; Gramignoli, R.; Jurga, M.; et al. Perinatal derivatives application: Identifying possibilities for clinical use. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 977590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Flores, A.I.; Pipino, C.; Jerman, U.D.; Liarte, S.; Gindraux, F.; Kreft, M.E.; Nicolas, F.J.; Pandolfi, A.; Tratnjek, L.; Giebel, B.; et al. Perinatal derivatives: How to best characterize their multimodal functions in vitro. Part C: Inflammation, angiogenesis, and wound healing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 965006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schmiedova, I.; Dembickaja, A.; Kiselakova, L.; Nowakova, B.; Slama, P. Using of Amniotic Membrane Derivatives for the Treatment of Chronic Wounds. Membranes 2021, 11, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kadkhoda, Z.; Tavakoli, A.; Chokami Rafiei, S.; Zolfaghari, F.; Akbari, S. Effect of Amniotic Membrane Dressing on Pain and Healing of Palatal Donor Site: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Organ. Transplant. Med. 2020, 11, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Horvath, V.; Svobodova, A.; Cabral, J.V.; Fiala, R.; Burkert, J.; Stadler, P.; Lindner, J.; Bednar, J.; Zemlickova, M.; Jirsova, K. Inter-placental variability is not a major factor affecting the healing efficiency of amniotic membrane when used for treating chronic non-healing wounds. Cell Tissue Bank. 2023, 24, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lacorzana, J. Amniotic Membrane, Clinical Applications and Tissue Engineering. Review of Its Ophthalmic Use. Arch. Soc. Española Oftalmol. 2020, 95, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svobodova, A.; Horvath, V.; Balogh, L.; Zemlickova, M.; Fiala, R.; Burkert, J.; Brabec, M.; Stadler, P.; Lindner, J.; Bednar, J.; et al. Outcome of Application of Cryopreserved Amniotic Membrane Grafts in the Treatment of Chronic Nonhealing Wounds of Different Origins in Polymorbid Patients: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Pathologies | Type of Wound/Location | Time of Evolution | Number of AM Applications | Time of Treatment | % Epithelialization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart disease, venous insufficiency, arterial hypertension, renal failure, peripheral arterial disease, diabetes mellitus type II (patient 1) | Right heel arterial ulcer | 6 months | 5 | 5 weeks | 100% |

| Cryoglobulinemia type I, multiple myeloma (patient 2) | Left foot, Achilles tendon | 2 months | 5 | 5 weeks | 100% |

| Calciphylaxis, severe kidney failure (patient 3) | Right knee | 12 months | 4 | 4 weeks | 100% |

| Diabetic foot, diabetes mellitus type II (patient 4) | Back of right foot | 10 months | 6 | 6 weeks | 100% |

| Fibromyalgia, lymphoproliferative autoimmune syndrome, rhizarthrosis, osteoporosis (patient 5) | Left leg, distal third of the tibia at the dorsal level | 4 years | 46 | 14 months | 40% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-Valiente, M.; García-Hernández, A.M.; Fuente-Mora, C.; Sánchez-Gálvez, J.; García-Vizcaino, E.M.; Tristante Barrenechea, E.; Castellanos Escrig, G.; Liarte Lastra, S.D.; Nicolás, F.J. Management of Foot Ulcers and Chronic Wounds with Amniotic Membrane in Comorbid Patients: A Successful Experience. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2380. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12102380

Rodríguez-Valiente M, García-Hernández AM, Fuente-Mora C, Sánchez-Gálvez J, García-Vizcaino EM, Tristante Barrenechea E, Castellanos Escrig G, Liarte Lastra SD, Nicolás FJ. Management of Foot Ulcers and Chronic Wounds with Amniotic Membrane in Comorbid Patients: A Successful Experience. Biomedicines. 2024; 12(10):2380. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12102380

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-Valiente, Mónica, Ana M. García-Hernández, Cristina Fuente-Mora, Javier Sánchez-Gálvez, Eva María García-Vizcaino, Elena Tristante Barrenechea, Gregorio Castellanos Escrig, Sergio David Liarte Lastra, and Francisco Jose Nicolás. 2024. "Management of Foot Ulcers and Chronic Wounds with Amniotic Membrane in Comorbid Patients: A Successful Experience" Biomedicines 12, no. 10: 2380. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12102380

APA StyleRodríguez-Valiente, M., García-Hernández, A. M., Fuente-Mora, C., Sánchez-Gálvez, J., García-Vizcaino, E. M., Tristante Barrenechea, E., Castellanos Escrig, G., Liarte Lastra, S. D., & Nicolás, F. J. (2024). Management of Foot Ulcers and Chronic Wounds with Amniotic Membrane in Comorbid Patients: A Successful Experience. Biomedicines, 12(10), 2380. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12102380