Ceruloplasmin, Catalase and Creatinine Concentrations Are Independently Associated with All-Cause Mortality in Patients with Advanced Heart Failure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

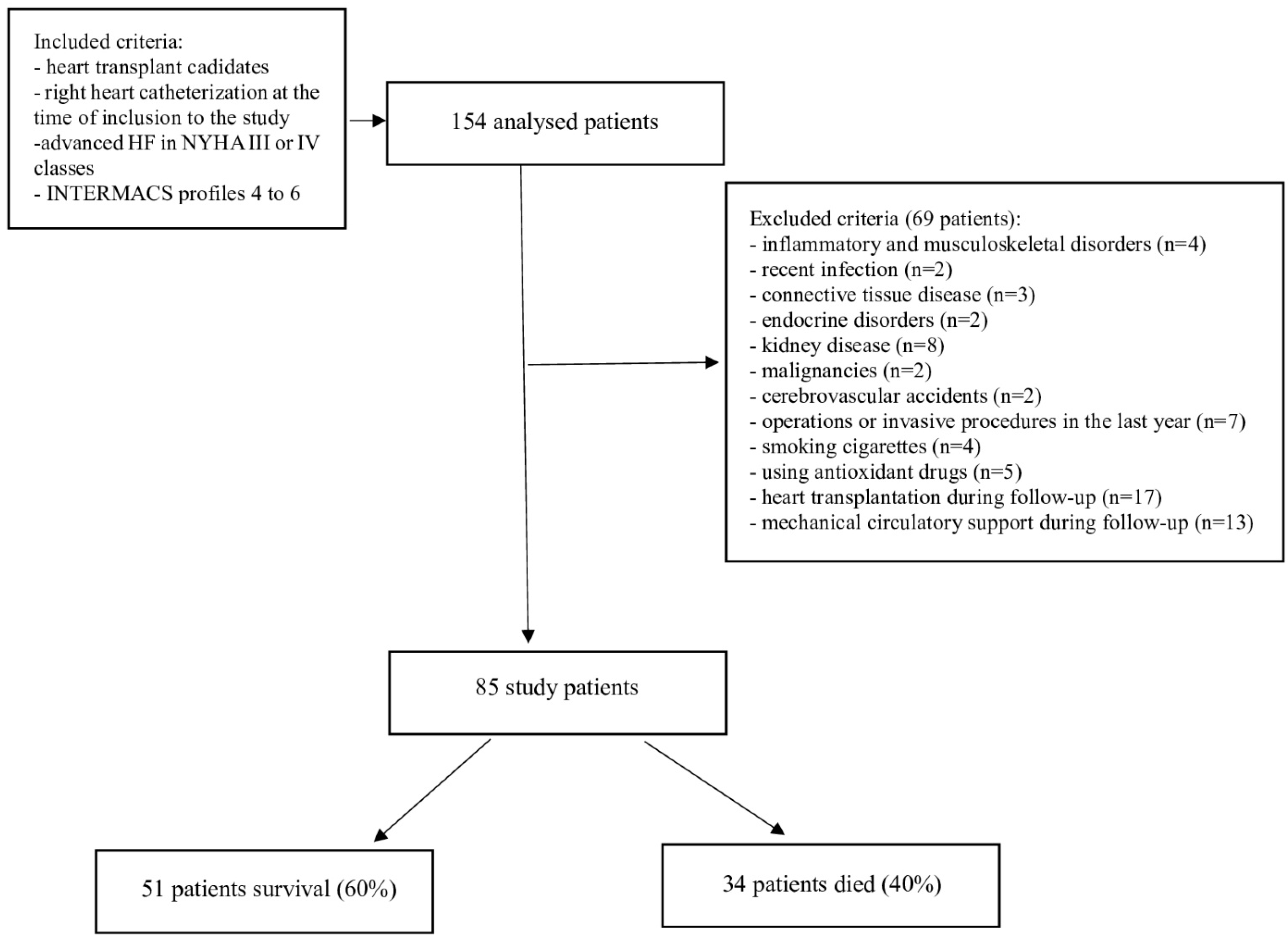

2.1. Study Population and Data Collection

2.2. Laboratory Measurements of Peripheral Blood

2.3. Laboratory Measurements of Coronary Sinus Blood Samples

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dröge, W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 47–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhalla, N.S.; Temsah, R.M.; Netticadan, T. Role of oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. J. Hypertens. 2000, 18, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotiadis, V.N.; Duchen, M.R.; Osellame, L.D. Mitochondrial quality control and communications with the nucleus are important in maintaining mitochondrial function and cell health. Biochim. Biophys Acta 2013, 1840, 1254–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera-Alberni, M.; Canto, C. Mitochondrial stress management: A dynamic journey. Cell Stress 2018, 2, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birben, E.; Sahiner, U.M.; Sackesen, C.; Erzurum, S.; Kalayci, O. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World Allergy Organ J. 2012, 5, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczurek, W.; Szyguła-Jurkiewicz, B. Oxidative stress and inflammatory markers—The future of heart failure diagnostics? Kardiochir. Torakochirurgia. Pol. 2015, 12, 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Xia, S.; Kalionis, B.; Wan, W.; Sun, T. The Role of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Cardiovascular Aging. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 615312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Pol, A.; van Gilst, W.H.; Voors, A.A.; van der Meer, P. Treating oxidative stress in heart failure: Past, present and future. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczurek-Wasilewicz, W.; Szyguła-Jurkiewicz, B.; Skrzypek, M.; Romuk, E.; Gąsior, M. Fetuin-A and sodium concentrations are independently associated with all-cause mortality in patients awaiting heart transplantation. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2021, 131, 16081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richterich, R. Clinical Chemistry: Theory and Practice; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Paglia, D.E.; Valentine, W.N. Studies on the quantitative and qualitative characterization of erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1967, 70, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habig, W.H.; Jakoby, W.B. Assays for differentiation of glutathione S-transferases. Methods Enzymol. 1981, 77, 398–405. [Google Scholar]

- Ōyanagui, Y. Reevaluation of assay methods and establishment of kit for superoxide dismutase activity. Anal. Biochem. 1984, 142, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984, 105, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa, H.; Ohishi, N.; Yagi, K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal. Biochem. 1979, 95, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Södergren, E.; Nourooz-Zadeh, J.; Berglund, L.; Vessby, B. Re-evaluation of the ferrous oxidation in xylenol orange assay for the measurement of plasma lipid hydroperoxides. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 1998, 37, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richterich, R.; Gautier, E.; Stillhart, H.; Rossi, E. The heterogeneity of caeruloplasmin nd the enzymatic defect in Wilson’s disease. Helv. Paediatr. Acta 1960, 15, 424–436. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, P.L.; Mazumder, B.; Ehrenwald, E.; Mukhopadhyay, C.K. Ceruloplasmin and cardiovascular disease. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 28, 1735–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, N.; Maher, J.; Masters, J.; Angelini, G.D.; Jeremy, J.Y. Does oxidative stress change ceruloplasmin from a protective to a vasculopathic factor? Atherosclerosis 2006, 187, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar-Poloczek, E.; Romuk, E.; Rozentryt, P.; Duda, S.; Gąsior, M.; Wojciechowska, C. Ceruloplasmin as Redox Marker Related to Heart Failure Severity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krsek-Staples, J.A.; Webster, R.O. Ceruloplasmin inhibits carbonyl formation in endogenous cell proteins. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1993, 14, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadu, R.T.; Dodge, R.; Nambi, V.; Virani, S.S.; Hoogeveen, R.C.; Smith, N.L.; Chen, F.; Pankow, J.S.; Guild, C.; Tang, W.W.; et al. Ceruloplasmin and heart failure in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Circ. Heart Fail. 2013, 6, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orena, S.J.; Goode, C.A.; Linder, M.C. Binding and uptake of copper from ceruloplasmin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1986, 139, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateeseu, M.; Chahine, R.; Roger, S.; Atanasiu, R. Protection of myocardical tissue against deleterious effects of oxygen free radicals by ceruloplasmin. Arzneim. Forsch/Drug Res. 1995, 45, 476–480. [Google Scholar]

- Chamine, R.; Mateescu, M.A.; Roger, S.; Yamaguchi, N.; de Champlain, J.; Nadeau, R. Protective effects of ceruloplasmin against electrolysis-induced oxygen free radicals in rat heart. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1991, 69, 1459–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderius, M.; Mostad, E.; Wendroth, K.; Prohaska, J.R. Levels of plasma ceruloplasmin protein are markedly lower following dietary copper deficiency in rodents. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010, 151, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderius, M.A.; Prohaska, J.R. Differential impact of copper deficiency in rats on blood cuproproteins. Nutr. Res. 2009, 29, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsherif, L.; Ortines, R.V.; Saari, J.T.; Kang, Y.J. Congestive Heart Failure in Copper-Deficient Mice. Exp. Biol. Med. 2003, 228, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, M.; Gagné, J.; Mateescu, M.-A.; Paquin, J. The effects of nitric oxide-oxidase and putative glutathione-peroxidase activities of ceruloplasmin on the viability of cardiomyocytes exposed to hydrogen peroxide. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 2019–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.W.; Wu, Y.; Hartiala, J.; Fan, Y.; Stewart, A.F.; Roberts, R.; McPherson, R.; Fox, P.L.; Allayee, H.; Hazen, S.L.; et al. Clinical and genetic association of serum ceruloplasmin with cardiovascular risk. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapryal, N.; Mukhopadhyay, C.; Das, D.; Fox, P.L. Mukhopadhyay CK. Reactive oxygen species regulate ceruloplasmin by a novel mRNA decay mechanism involving its 3′-untranslated region: Implications in neurodegenerative diseases. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 3, 1873–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, I.M.; Kaplan, H.B.; Edelson, H.S.; Weissmann, G. Ceruloplasmin. A scavenger of superoxide anion radicals. J. Biol. Chem. 1979, 10, 4040–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugrin, J.; Rosenblatt-Velin, N.; Parapanov, R.; Liaudet, L. The role of oxidative stress during inflammatory processes. Biol. Chem. 2013, 395, 203–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, Y.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide radical inhibits catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 5751–5754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szyller, J.; Antoniak, R.; Wadowska, K.; Bil-Lula, I.; Hrymniak, B.; Banasiak, W.; Jagielski, D. Redox imbalance in patients with heart failure and ICD/CRT-D intervention. Can it be an underappreciated and overlooked arrhythmogenic factor? A first preliminary clinical study. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1289587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, T.; Tsutsui, H.; Kinugawa, S.; Suematsu, N.; Hayashidani, S.; Ichikawa, K.; Utsumi, H.; Machida, Y.; Egashira, K.; Takeshita, A. Direct evidence for increased hydroxyl radicals originating from superoxide in the failing myocardium. Circ. Res. 2000, 86, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Lennon-Edwards, S.; Lancel, S.; Biolo, A.; Siwik, D.A.; Pimentel, D.R.; Dorn, G.W.; Kang, Y.J.; Colucci, W.S. Cardiac-specific overexpression of catalase identifies hydrogen peroxide-dependent and -independent phases of myocardial remodeling and prevents the progression to overt heart failure in G(alpha)q-overexpressing transgenic mice. Circ. Heart Fail. 2010, 2, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwik, D.A.; Pagano, P.J.; Colucci, W.S. Oxidative stress regulates collagen synthesis and matrix metalloproteinase activity in cardiac fibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Phisiol. 2001, 280, C53–C60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwik, D.A.; Chang, D.L.; Colucci, W.S. Interleukin-1beta and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha Decrease Collagen Synthesis and Increase Matrix Metalloproteinase Activity in Cardiac Fibroblasts In Vitro. Circ. Res. 2000, 86, 1259–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäumer, A.T.; Flesch, M.; Wang, X.; Shen, Q.; Feuerstein, G.Z.; Böhm, M. Antioxidative enzymes in human hearts with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2000, 1, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giamouzis, G.; Butler, J.; Triposkiadis, F. Renal function in advanced heart failure. Congest. Heart Fail. 2011, 17, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damman, K.; Navis, G.; Smilde, T.D.; Voors, A.A.; van der Bij, W.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Hillege, H.L. Decreased cardiac output, venous congestion and the association with renal impairment in patients with cardiac dysfunction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2007, 9, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nohria, A.; Hasselblad, V.; Stebbins, A.; Pauly, D.F.; Fonarow, G.C.; Shah, M.; Yancy, C.W.; Califf, R.M.; Stevenson, L.W.; Hill, J.A. Cardiorenal interactions: Insights from the ESCAPE trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 51, 1268–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, E.A. Congestive Renal Failure: The Pathophysiology and Treatment of Renal Venous Hypertension. J. Card. Fail. 2012, 18, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picano, E.; Morales, M.A.; del Ry, S.; Sicari, R. Innate inflammation in myocardial perfusion and its implication for heart failure. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1207, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fildes, J.E.; Shaw, S.M.; Yonan, N.; Williams, S.G. The immune system and chronic heart failure: Is the heart in control? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 12, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpeinen, A.K.; Vanninen, E.; Magga, J.; Tuomainen, P.; Kuusisto, J.; Sipola, P.; Punnonen, K.; Vuolteenaho, O.; Peuhkurinen, K. Cardiac sympathetic activity is associated with inflammation and neurohumoral activation in patients with idiopathic dilated cardio-myopathy. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2009, 6, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottone, S.; Lorito, M.C.; Riccobene, R.; Nardi, E.; Mulè, G.; Buscemi, S.; Geraci, C.; Guarneri, M.; Arsena, R.; Cerasola, G. Oxidative stress, inflammation and cardiovascular disease in chronic renal failure. J. Nephrol. 2008, 21, 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Chiong, J.R.; Cheung, R.J. Loop diuretic therapy in heart failure: The need for solid evidence on a fluid issue. Clin. Cardiol. 2010, 6, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFadyen, R.J.; Ng Kam Chuen, M.J.; Davis, R.C. Loop diuretic therapy in left ventricular systolic dysfunction: Has familiarity bred contempt for a critical but potentially nephrotoxic cardiorenal therapy? Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2010, 7, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, D.H. Diuretic therapy and resistance in congestive heart failure. Cardiology 2001, 96, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triposkiadis, F.; Karayannis, G.; Giamouzis, G.; Skoularigis, J.; Louridas, G.; Butler, J. The sympathetic nervous system in heart failure: Physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical implications. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 19, 1747–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loon, N.R.; Wilcox, C.S.; Unwin, R.J. Mechanism of impaired natriuretic response to furosemide during prolonged therapy. Kidney Int. 1989, 4, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeshari, K.; Ahlstrom, N.G.; Capraro, F.E.; Wilcox, C.S. A volume-independent component to postdiuretic sodium retention in humans. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1993, 3, 1878–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Whole Population N = 85 # | Survival N = 51 | Nonsurvival N = 34 | p * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline data | ||||

| Age, years | 58.00 (50.0–62.0) | 58.00 (53.5–61.5) | 57.5 (47.2–63.4) | 0.7779 |

| Male, n (%) | 77 (90.6) | 45 (88.2) | 32 (94.1) | 0.3629 |

| Ischemic etiology of HF, n (%) | 52 (61.2) | 34 (66.7) | 18 (52.9) | 0.2137 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.6 (24.1–30.4) | 28.1 (24.1–30.1) | 28.9 (25.9–30.1) | 0.377 |

| INTERMACS profiles | ||||

| Profile 4 | 15 (17.6) | 7 (13.7) | 8 (23.5) | 0.298 |

| Profile 5 | 32 (37.6) | 18 (35.3) | 14 (41.2) | |

| Profile 6 | 38 (44.7) | 26 (51) | 12 (35.3) | |

| Inotropic support during follow-up, n (%) | 10 (11.8) | 6 (11.8) | 4 (11.8) | 1.000 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 50 (58.8) | 33 (64.7) | 17 (50.0) | 0.1771 |

| Type 2 diabetes, n (%) | 41 (48.2) | 22 (43.1) | 19 (55.9) | 0.2493 |

| Persistent AF, n (%) | 38 (44.7) | 22 (43.1) | 16 (47.1) | 0.7217 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 62 (72.9) | 38 (74.5) | 24 (70.6) | 0.6901 |

| Laboratory parameters from peripheral blood samples | ||||

| WBC, ×109/L | 6.6 (5.4–8.4) | 6.7 (5.5–8.3) | 6.9 (6.1–7.7) | 0.9001 |

| Hemoglobin, mmol/L | 8.5 (0.92) | 8.5 (0.94) | 8.4 (1.2) | 0.9311 |

| Creatinine, µmol/L | 116.0 (95.0–138.0) | 101.0 (90.1–124.2) | 134.1 (111.0–159.0) | <0.0001 * |

| Platelets, ×109/L | 182.00 (48.1) | 190.1 (48.1) | 168.9 (46.75) | 0.0603 |

| Total bilirubin, µmol/L | 21.4 (14.7–35.5) | 20.7 (14.0–35.5) | 23.3 (17.00–34.00) | 0.5317 |

| Uric acid, µmol/L | 477.9 (149.9) | 473.8 (145.5) | 484.1 (158.3) | 0.7702 |

| Urea, µmol/L | 9.2 (6.6–13.2) | 7.90 (5.4–11.9) | 11.7 (8.5–17.1) | 0.0068 * |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 139.0 (136.0–141.0) | 139.0 (138.0–142.0) | 136.0 (135.0–139.0) | 0.0003 * |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | 382.0 (301.0–482.0) | 343.0 (282.0–450.0) | 407.0 (375.0–494.0) | 0.0005 * |

| AST, U/L | 27.0 (22.2–35.2) | 27.0 (23.0–37.0) | 27.0 (22.0–34.0) | 0.2964 |

| ALT, U/L | 25.0 (17.0–36.0) | 26.0 (22.00–40.00) | 21.1 (16.0–26.0) | 0.0129 * |

| Cholesterol, mmol/L | 3.7 (3.4–4.4) | 4.2 (3.1–4.7) | 3.3 (2.2–4.3) | 0.4115 |

| hs-CRP, mg/L | 2.7 (1.6–6.1) | 1.8 (1.3–4.9) | 4.6 (2.7–8.1) | 0.0067 * |

| ESR, mm/h | 13.3 (6.8) | 9.3 (3.6) | 19.4 (5.7) | <0.0001 * |

| HBA1c, % | 6.1 (0.8) | 5.8 (0.8) | 6.2 (0.8) | 0.1651 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 3788.0 (2017.0–5799.0) | 3131.0 (1687.0–6473.0) | 4307.0 (3352.0–5670.0) | 0.0729 |

| Oxidative/antioxidative parameters from coronary sinus samples | ||||

| CAT kIU/g Hb | 453.4 (363.0–597.3) | 58.1 (466.8–684.3) | 345.5 (313.7–392.2) | <0.0001 * |

| SOD NU/mL | 20.1 (17.3–23.5) | 21.9 (3.9) | 19.7 (3.4) | 0.0075 * |

| MnSOD NU/mL | 13.2 (10.1–17.7) | 15.7 (12.1–20.5) | 11.9 (8.7–16.6) | 0.0051 * |

| CuZnSOD, NU/mL | 6.2 (4.8–8.2) | 7.0 (4.8–8.3) | 5.7 (4.7–7.6) | 0.2078 |

| LPH μmol/L | 1.3 (0.8–1.9) | 0.8 (0.6–1.6) | 1.9 (1.6–2.4) | <0.0001 * |

| GR, IU/g Hb | 10.2 (9.0–10.8) | 10.3 (10.0–11.3) | 10.0 (8.5–10.5) | 0.0437 * |

| GPX, IU/g Hb | 51.4 (37.8–63.9) | 59.9 (20.3) | 41.1 (12.7) | <0.0001 * |

| GST, IU/g Hb | 0.36 (0.29–0.42) | 0.36 (0.28–0.41) | 0.37 (0.30–0.43) | 0.4746 |

| CER, mg/dL | 40.2 (35.8–47.7) | 46.7 (42.8–49.8) | 35.6 (32.2–38.0) | <0.0001 * |

| MDA, μmol/L | 3.7 (1.1) | 3.0 (0.5) | 4.6 (0.84) | <0.0001 * |

| Hemodynamic parameters | ||||

| mPAP, mmHg | 27.5 (8.9) | 27.6 (9.7) | 27.3 (7.9) | 0.8565 |

| CI, L/min/m2 | 1.8 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.2) | 0.6113 |

| TPG, mmHg | 8.0 (7.0–11.0) | 8.0 (7.0–10.0) | 8.0 (7.0–11.0) | 0.8854 |

| PVR, Wood units | 2.1 (1.9–2.5) | 2.1 (1.9–2.4) | 2.2 (1.8–2.6) | 0.5435 |

| Spirometry | ||||

| FEV1, % | 77.9 (13.4) | 76.9 (14.6) | 79.4 (11.5) | 0.4169 |

| FVC, % | 83.0 (74.0–92.0) | 83.0 (74.0–88.0) | 85.5 (75.0–94.0) | 0.1875 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 97.0 (93.0–102.0) | 98.0 (94.0–103.0) | 97.0 (92.0–101.0) | 0.6739 |

| Echocardiographic parameters | ||||

| LA, mm | 54.6 (7.8) | 52.8 (8.4) | 57.5 (5.9) | 0.0032 * |

| RVEDd, mm | 32.00 (30.0–35.0) | 32.0 (29.0–35.0) | 33.0 (30.0–35.0) | 0.3608 |

| LVEDd, mm | 75.1 (9.8) | 73.2 (9.8) | 77.8 (9.3) | 0.0326 * |

| LVEF, % | 16.00 (15.0–18.0) | 16.0 (15.0–18.0) | 16.0 (15.0–18.0) | 0.7297 |

| Cardiac medications | ||||

| B-blockers, n (%) | 85 (100) | 51 (100) | 34 (100) | 1.000 |

| Metoprolol succinate dose, mg/day | 100.00 (100.00–150.00) | 100.00 (100.00–150.00) | 100.00 (100.00–150.00) | 0.9915 |

| Bisoprolol dose, mg/day | 7.50 (5.00–10.00) | 7.50 (5.00–10.00) | 6.25 (5.00–10.00) | 0.5959 |

| Carvedilol dose, mg/day | 50.00 (25.00–50.00) | 37.50 (25.00–50.00) | 50.00 (25.00–50.00) | 1.000 |

| ACEI/ARB, n (%) | 83 (97.6) | 50 (98.0) | 33 (97.1) | 0.7702 |

| Perindopril dose, mg/day | 5.00 (5.00–7.50) | 5.00 (5.00–7.50) | 5.00 (5.00–7.50) | 1.000 |

| Ramipril dose, mg/day | 5.00 (5.00–7.50) | 5.00 (5.00–7.50) | 5.00 (5.00–7.50) | 0.8499 |

| Valsartan dose, mg/day | 160.00 (80.00–320.00) | 160.00 (120.00–240.00) | 160.00 (80.00–320.00) | 1.000 |

| Loop diuretics, n (%) | 82 (96.5) | 48 (94.1) | 34 (100) | 0.1499 |

| Furosemide dose, mg/day ^ | 120.00 (80.00–160.00) | 120.0 (80.0–160.0) | 120.0 (80.0–160.0) | 0.889 |

| MRA, n (%) | 85 (100) | 51 (100) | 34 (100) | 1.000 |

| Spironolactone dose, mg/day | 50.00 (25.00–50.00) | 50.0 (25.0–50.0) | 50.0 (25.0–50.0) | 0.7672 |

| Epleronone dose, mg/day | 50.00 (25.00–50.00) | 50.0 (25.0–50.0) | 50.0 (25.0–50.0) | 0.3497 |

| Digoxin, n (%) | 33 (38.8) | 20 (39.2) | 13 (38.2) | 0.9276 |

| Digoxin dose, μg/day | 0.25 (0.10–0.25) | 0.18 (0.10–0.25) | 0.25 (0.10–0.25) | 0.8494 |

| Ivabradine, n (%) | 17 (20) | 14 (27.5) | 3 (8.8) | 0.0354 * |

| Ivabradine dose, mg/day | 10.00 (10.00–15.00) | 10.00 (10.00–15.00) | 10.00 (10.00–15.00) | 1.000 |

| Statins, n (%) | 70 (82.4) | 42 (82.4) | 28 (82.4) | 1.000 |

| Acetylsalicylic acid, n (%) | 31 (36.5) | 19 (37.3) | 12 (35.3) | 0.8540 |

| Vitamin K antagonists, n (%) | 52 (61.2) | 33 (64.7) | 19 (55.9) | 0.4135 |

| ICD/CRT-D, n (%) | 85 (100) | 51 (100) | 34 (100) | 1.000 |

| Other | ||||

| VO2 max, mL/kg/min | 10. 60 (9.70–11.60) | 11.20 (10.20–12.00) | 10.20 (9.00–11.40) | 0.0094 * |

| Parameter | Univariable Regression | Multivariable Regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| CER (−) * | 1.439 (1.230–1.684) | <0.0001 | 1.342 (1.019–1.770) | 0.0363 |

| LPH (+) * | 7.525 (3.011–18.808) | <0.0001 | ||

| CAT (−) * | 1.038 (1.019–1.057) | <0.0001 | 1.053 (1.014–1.093) | 0.0076 |

| GPX (−) * | 1.066 (1.031–1.101) | 0.0001 | ||

| SOD (−) * | 1.178 (1.039–1.336) | 0.0104 | ||

| Fibrinogen (+) # | 1.008(1.003–1.012) | 0.0013 | ||

| Urea (+) # | 1.121 (1.028–1.223) | 0.0097 | ||

| Sodium (−) # | 1.340 (1.142–1.575) | 0.0004 | ||

| ESR (+) # | 1.667 (1.343–2.070) | 0.0261 | ||

| Creatinine (+) # | 1.037 (1.018–1.057) | 0.0001 | 1.071 (1.002–1.144) | 0.0422 |

| VO2 max (−) # | 1.391 (1.071–1.805) | 0.0134 | ||

| AUC [±95 CI] | Cutoff | Sensitivity [±95 CI] | Specificity [±95 CI] | PPV [±95 CI] | NPV [±95 CI] | Accuracy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CER | 0.9296 [0.8738–0.9855] | ≤39.4 | 0.94 [ 0.80–0.99] | 0.86 [0.74–0.94] | 0.82 [0.66–0.92] | 0.96 [0.85–0.99] | 0.89 [0.80–0.95] |

| CAT | 0.9666 [0.9360–0.9971] | ≤426.4 | 0.91 [0.76–0.98] | 0.90 [0.79–0.97] | 0.86 [0.70–0.95] | 0.94 [0.83–0.99] | 0.90 [0.82–0.96] |

| Creatinine | 0.7682 [0.6607–0.8756] | ≥105 | 0.85 [0.69–0.95] | 0.59 [0.44–0.72] | 0.58 [0.43–0.72] | 0.86 [0.70–0.95] | 0.69 [0.58–0.79] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smyła-Gruca, W.; Szczurek-Wasilewicz, W.; Skrzypek, M.; Karmański, A.; Romuk, E.; Jurkiewicz, M.; Gąsior, M.; Szyguła-Jurkiewicz, B. Ceruloplasmin, Catalase and Creatinine Concentrations Are Independently Associated with All-Cause Mortality in Patients with Advanced Heart Failure. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 662. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12030662

Smyła-Gruca W, Szczurek-Wasilewicz W, Skrzypek M, Karmański A, Romuk E, Jurkiewicz M, Gąsior M, Szyguła-Jurkiewicz B. Ceruloplasmin, Catalase and Creatinine Concentrations Are Independently Associated with All-Cause Mortality in Patients with Advanced Heart Failure. Biomedicines. 2024; 12(3):662. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12030662

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmyła-Gruca, Wiktoria, Wioletta Szczurek-Wasilewicz, Michał Skrzypek, Andrzej Karmański, Ewa Romuk, Michał Jurkiewicz, Mariusz Gąsior, and Bożena Szyguła-Jurkiewicz. 2024. "Ceruloplasmin, Catalase and Creatinine Concentrations Are Independently Associated with All-Cause Mortality in Patients with Advanced Heart Failure" Biomedicines 12, no. 3: 662. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12030662

APA StyleSmyła-Gruca, W., Szczurek-Wasilewicz, W., Skrzypek, M., Karmański, A., Romuk, E., Jurkiewicz, M., Gąsior, M., & Szyguła-Jurkiewicz, B. (2024). Ceruloplasmin, Catalase and Creatinine Concentrations Are Independently Associated with All-Cause Mortality in Patients with Advanced Heart Failure. Biomedicines, 12(3), 662. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12030662