Thyroid Hormones in Early Pregnancy and Birth Weight: A Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

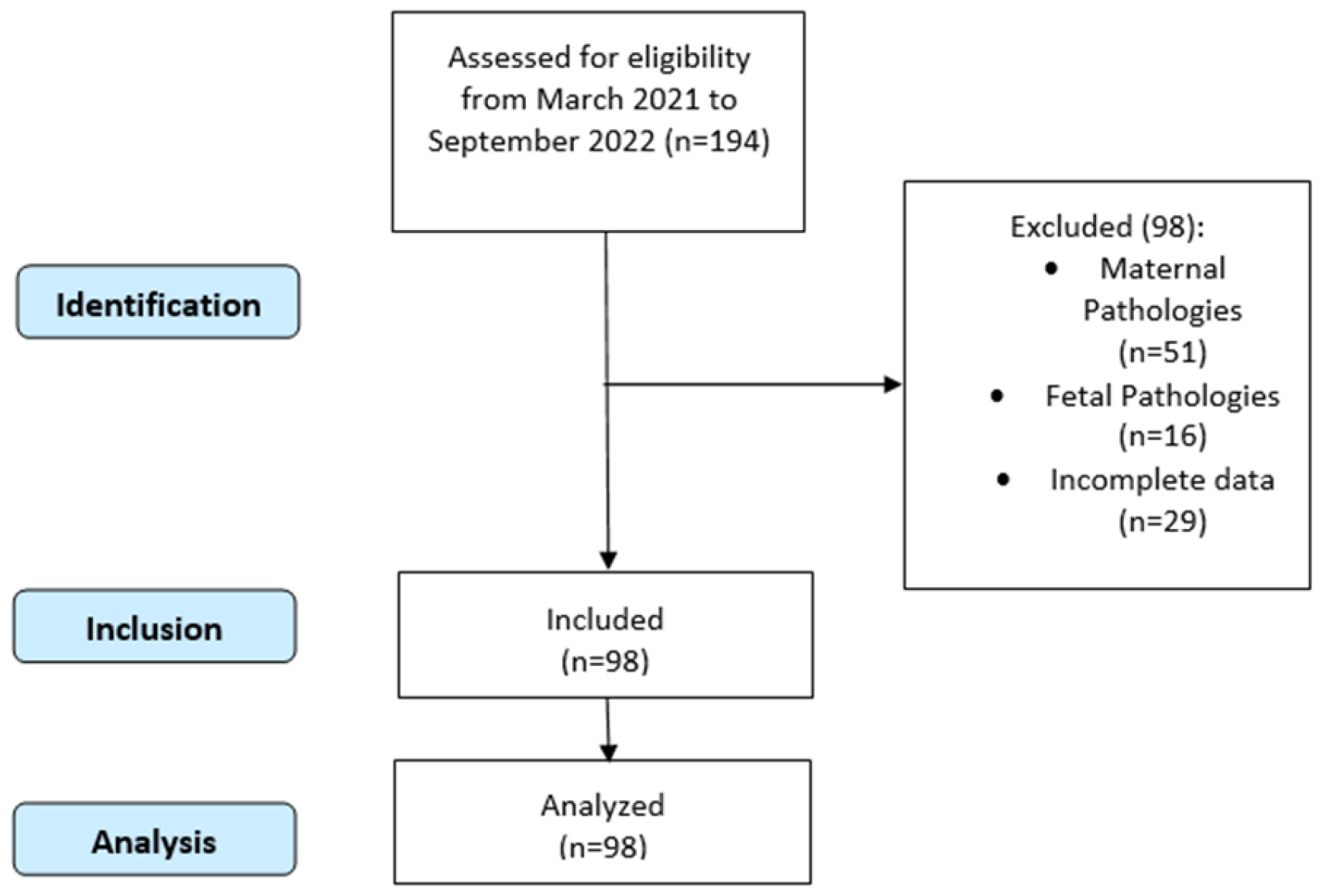

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Thyroid Function and Pregnancy

4.2. Thyroid Dysfunction and Pregnancy

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stagnaro-Green, A.; Pearce, E. Thyroid disorders in pregnancy. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J.H. Thyroid function in pregnancy. Br. Med. Bull. 2011, 97, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, D.; Jiskra, J.; Limanova, Z.; Zima, T.; Potlukova, E. Thyroid in pregnancy: From physiology to screening. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2017, 54, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemu, A.; Terefe, B.; Abebe, M.; Biadgo, B. Thyroid hormone dysfunction during pregnancy: A review. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2016, 14, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Koenig, R.J. Gene regulation by thyroid hormone. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 11, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moog, N.K.; Entringer, S.; Heim, C.; Wadhwa, P.D.; Kathmann, N.; Buss, C. Influence of maternal thyroid hormones during gestation on fetal brain development. Neuroscience 2017, 342, 68–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, J.D.; Williams, G.R. Role of thyroid hormones in skeletal development and bone maintenance. Endocr. Rev. 2016, 37, 135–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maraka, S.; Ospina, N.M.S.; O’Keeffe, D.T.; Espinosa De Ycaza, A.E.; Gionfriddo, M.R.; Erwin, P.J.; Coddington, C.C., III; Stan, M.N.; Murad, M.H.; Montori, V.M. Subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid 2016, 26, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shao, Y.Y.; Ballock, R.T. Thyroid hormone-mediated growth and differentiation of growth plate chondrocytes involves IGF-1 modulation of β-catenin signaling. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 1138–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, F.; Yang, S.; Peeters, R.P.; Korevaar, T.I.; Fan, J.; Huang, H.-F. Association between maternal thyroid hormones and birth weight at early and late pregnancy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 5853–5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantz, C.R.; Dagogo-Jack, S.; Ladenson, J.H.; Gronowski, A.M. Thyroid function during pregnancy. Clin. Chem. 1999, 45, 2250–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medici, M.; de Rijke, Y.B.; Peeters, R.P.; Visser, W.; de Muinck Keizer-Schrama, S.M.; Jaddoe, V.V.; Hofman, A.; Hooijkaas, H.; Steegers, E.A.; Tiemeier, H. Maternal early pregnancy and newborn thyroid hormone parameters: The Generation R study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stagnaro-Green, A. Maternal thyroid disease and preterm delivery. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Luo, J.; Wang, X.; Yuan, L.; Guo, L. Association of thyroid disorders with gestational diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. Endocrine 2021, 73, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okosieme, O.E.; Lazarus, J.H. Thyroid dysfunction in pregnancy: Optimizing fetal and maternal outcomes. Expert Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 5, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, S. Pitfalls in the assessment of gestational transient thyrotoxicosis. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2020, 36, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidya, B.; Anthony, S.; Bilous, M.; Shields, B.; Drury, J.; Hutchison, S.; Bilous, R. Detection of thyroid dysfunction in early pregnancy: Universal screening or targeted high-risk case finding? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Escobar, G.M.; Obregón, M.J.; del Rey, F.E. Maternal thyroid hormones early in pregnancy and fetal brain development. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 18, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitoris, G.; Veltri, F.; Kleynen, P.; Cogan, A.; Belhomme, J.; Rozenberg, S.; Pepersack, T.; Poppe, K. The impact of thyroid disorders on clinical pregnancy outcomes in a real-world study setting. Thyroid 2020, 30, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Bansal, R.; Shergill, H.K.; Garg, P. Prevalence of thyroid dysfunction in pregnancy and its association with feto-maternal outcomes: A prospective observational study from a tertiary care institute in Northern India. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2023, 19, 101201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Ye, M.; Zhou, Z.; Yuan, L.; Lash, G.E.; Zhang, G.; Li, L. Reference values and the effect of clinical parameters on thyroid hormone levels during early pregnancy. Biosci. Rep. 2021, 41, BSR20202296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, S.L.; Andersen, S.; Liew, Z.; Vestergaard, P.; Olsen, J. Maternal thyroid function in early pregnancy and neuropsychological performance of the child at 5 years of age. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, J.E.; Faix, J.E.; Hermos, R.J.; Mullaney, D.M.; Rojan, D.A.; Mitchell, M.L.; Klein, R.Z. Thyroid function in very low birth weight infants: Effects on neonatal hypothyroidism screening. J. Pediatr. 1996, 128, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, C.; Luo, M.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Guo, L.; Lu, C. Association between maternal lifestyle factors and low birth weight in preterm and term births: A case-control study. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warrington, N.M.; Beaumont, R.N.; Horikoshi, M.; Day, F.R.; Helgeland, Ø.; Laurin, C.; Bacelis, J.; Peng, S.; Hao, K.; Feenstra, B. Maternal and fetal genetic effects on birth weight and their relevance to cardio-metabolic risk factors. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Verde, M.; Riemma, G.; Torella, M.; Torre, C.; Cianci, S.; Conte, A.; Capristo, C.; Morlando, M.; Colacurci, N.; De Franciscis, P. Impact of Braxton-Hicks contractions on fetal wellbeing; a prospective analysis through computerised cardiotocography. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 42, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Verde, M.; Luciano, M.; Fordellone, M.; Brandi, C.; Carbone, M.; Di Vincenzo, M.; Lettieri, D.; Palma, M.; Marrapodi, M.M.; Scalzone, G. Is there a correlation between prepartum anaemia and an increased likelihood of developing postpartum depression? A prospective observational study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 310, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salafia, C.M.; Charles, A.K.; Maas, E.M. Placenta and fetal growth restriction. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 49, 236–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, N.; Quant, H.S.; Sammel, M.D.; Parry, S. Macrosomia has its roots in early placental development. Placenta 2014, 35, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordijn, S.; Beune, I.; Thilaganathan, B.; Papageorghiou, A.; Baschat, A.; Baker, P.; Silver, R.; Wynia, K.; Ganzevoort, W. Consensus definition of fetal growth restriction: A Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 48, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, O. Fetal macrosomia: Etiologic factors. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 43, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, M.; Johansson, S.; Villamor, E.; Cnattingius, S. Maternal overweight and obesity and risks of severe birth-asphyxia-related complications in term infants: A population-based cohort study in Sweden. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, J.P. Fetal growth and well-being. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. 2004, 31, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narain, S.; McEwan, A. Antenatal assessment of fetal well-being. Obstet. Gynaecol. Reprod. Med. 2023, 33, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Sharma, A.J.; Sappenfield, W.; Wilson, H.G.; Salihu, H.M. Association of maternal body mass index, excessive weight gain, and gestational diabetes mellitus with large-for-gestational-age births. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 123, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Verde, M.; Torella, M.; Riemma, G.; Narciso, G.; Iavarone, I.; Gliubizzi, L.; Palma, M.; Morlando, M.; Colacurci, N.; De Franciscis, P. Incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus before and after the COVID-19 lockdown: A retrospective cohort study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2022, 48, 1126–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Verde, M.; Torella, M.; Ronsini, C.; Riemma, G.; Cobellis, L.; Marrapodi, M.M.; Capristo, C.; Rapisarda, A.M.C.; Morlando, M.; De Franciscis, P. The association between fetal Doppler and uterine artery blood volume flow in term pregnancies: A pilot study. Ultraschall Med.-Eur. J. Ultrasound 2023, 45, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roland, M.C.P.; Friis, C.M.; Godang, K.; Bollerslev, J.; Haugen, G.; Henriksen, T. Maternal factors associated with fetal growth and birthweight are independent determinants of placental weight and exhibit differential effects by fetal sex. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hokken-Koelega, A.C.; van der Steen, M.; Boguszewski, M.C.; Cianfarani, S.; Dahlgren, J.; Horikawa, R.; Mericq, V.; Rapaport, R.; Alherbish, A.; Braslavsky, D. International consensus guideline on small for gestational age: Etiology and management from infancy to early adulthood. Endocr. Rev. 2023, 44, 539–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, E.A.; Peixoto, A.B.; Zamarian, A.C.P.; Júnior, J.E.; Tonni, G. Macrosomia. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017, 38, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, E.; Duval, F.; Vialard, F.; Dieudonné, M.-N. The roles of leptin and adiponectin at the fetal-maternal interface in humans. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2015, 24, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Verde, M.; De Franciscis, P.; Torre, C.; Celardo, A.; Grassini, G.; Papa, R.; Cianci, S.; Capristo, C.; Morlando, M.; Riemma, G. Accuracy of fetal biacromial diameter and derived ultrasonographic parameters to predict shoulder dystocia: A prospective observational study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadbeigi, A.; Farhadifar, F.; Zadeh, N.S.; Mohammadsalehi, N.; Rezaiee, M.; Aghaei, M. Fetal macrosomia: Risk factors, maternal, and perinatal outcome. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 2013, 3, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hillier, T.A.; Pedula, K.L.; Vesco, K.K.; Schmidt, M.M.; Mullen, J.A.; LeBlanc, E.S.; Pettitt, D.J. Excess gestational weight gain: Modifying fetal macrosomia risk associated with maternal glucose. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 112, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Beckerath, A.-K.; Kollmann, M.; Rotky-Fast, C.; Karpf, E.; Lang, U.; Klaritsch, P. Perinatal complications and long-term neurodevelopmental outcome of infants with intrauterine growth restriction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 208, 130.e1–130.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, E.; Wu, J.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Q.; Walker, M.; Mbikay, M.; Sigal, R.; Nair, R.; Wen, S. Fetal macrosomia and adolescence obesity: Results from a longitudinal cohort study. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 923–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangaratinam, S.; Rogozińska, E.; Jolly, K.; Glinkowski, S.; Roseboom, T.; Tomlinson, J.; Kunz, R.; Mol, B.; Coomarasamy, A.; Khan, K.S. Effects of interventions in pregnancy on maternal weight and obstetric outcomes: Meta-analysis of randomised evidence. BMJ 2012, 344, e2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spada, E.; Chiossi, G.; Coscia, A.; Monari, F.; Facchinetti, F. Effect of maternal age, height, BMI and ethnicity on birth weight: An Italian multicenter study. J. Perinat. Med. 2018, 46, 1016–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.; Landers, K.; Li, H.; Mortimer, R.; Richard, K. Thyroid hormones and fetal neurological development. J. Endocrinol. 2011, 209, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishioka, E.; Hirayama, S.; Ueno, T.; Matsukawa, T.; Vigeh, M.; Yokoyama, K.; Makino, S.; Takeda, S.; Miida, T. Relationship between maternal thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) elevation during pregnancy and low birth weight: A longitudinal study of apparently healthy urban Japanese women at very low risk. Early Hum. Dev. 2015, 91, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, K.; Guo, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, M.; Xie, Z.; Chen, P.; Wu, B.; Lin, N. Small for gestational age is a risk factor for thyroid dysfunction in preterm newborns. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardridge, W.M. Transport of protein-bound hormones into tissues in vivo. Endocr. Rev. 1981, 2, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, G.G.; Kester, M.H.; Peeters, R.P.; Visser, T.J. Biochemical mechanisms of thyroid hormone deiodination. Thyroid 2005, 15, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yang, X.; Yang, S.; Meng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Peeters, R.P.; Huang, H.-F.; Korevaar, T.I.; Fan, J. Association of maternal thyroid function and thyroidal response to human chorionic gonadotropin with early fetal growth. Thyroid 2019, 29, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korevaar, T.I.; Chaker, L.; Medici, M.; de Rijke, Y.B.; Jaddoe, V.W.; Steegers, E.A.; Tiemeier, H.; Visser, T.J.; Peeters, R.P. Maternal total T4 during the first half of pregnancy: Physiologic aspects and the risk of adverse outcomes in comparison with free T4. Clin. Endocrinol. 2016, 85, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Chen, Y.; Cai, W.-Q.; Liu, L.; Hu, X.-J. Effect of gestational weight gain on associations between maternal thyroid hormones and birth outcomes. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boas, M.; Forman, J.L.; Juul, A.; Feldt-Rasmussen, U.; Skakkebaek, N.E.; Hilsted, L.; Chellakooty, M.; Larsen, T.; Larsen, J.F.; Petersen, J.H. Narrow intra-individual variation of maternal thyroid function in pregnancy based on a longitudinal study on 132 women. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2009, 161, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moleti, M.; Trimarchi, F.; Vermiglio, F. Thyroid physiology in pregnancy. Endocr. Pract. 2014, 20, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, P.-Y.; Huang, K.; Hao, J.-H.; Xu, Y.-Q.; Yan, S.-Q.; Li, T.; Xu, Y.-H.; Tao, F.-B. Maternal thyroid function in the first twenty weeks of pregnancy and subsequent fetal and infant development: A prospective population-based cohort study in China. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 3234–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morreale de Escobar, G.; Obregón, M.J.; Escobar del Rey, F. Role of thyroid hormone during early brain development. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2004, 151 (Suppl. S3), U25–U37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbib, N.; Hadar, E.; Sneh-Arbib, O.; Chen, R.; Wiznitzer, A.; Gabbay-Benziv, R. First trimester thyroid stimulating hormone as an independent risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcome. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017, 30, 2174–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakosta, P.; Alegakis, D.; Georgiou, V.; Roumeliotaki, T.; Fthenou, E.; Vassilaki, M.; Boumpas, D.; Castanas, E.; Kogevinas, M.; Chatzi, L. Thyroid dysfunction and autoantibodies in early pregnancy are associated with increased risk of gestational diabetes and adverse birth outcomes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 4464–4472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneuer, F.J.; Nassar, N.; Tasevski, V.; Morris, J.M.; Roberts, C.L. Association and predictive accuracy of high TSH serum levels in first trimester and adverse pregnancy outcomes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 3115–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moleti, M.; Di Mauro, M.; Sturniolo, G.; Russo, M.; Vermiglio, F. Hyperthyroidism in the pregnant woman: Maternal and fetal aspects. J. Clin. Transl. Endocrinol. 2019, 16, 100190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krassas, G.; Poppe, K.; Glinoer, D. Thyroid function and human reproductive health. Endocr. Rev. 2010, 31, 702–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Pearce, E.N. Assessment and treatment of thyroid disorders in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandrupkar, G.G. Screening Thyroid Disorders during Pregnancy. Handb. Antenatal Care 2020, 4, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Mainali, S.; Kayastha, S.; Devkota, S.; Yadav, P.; Bharati, B.; Upadhyay, S.; Maharjan, S.; Manandhar, S.; Timilsina, L. Screening for Thyroid Disorder in First Trimester of Pregnancy: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 12, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo Lara, M.; Vilar Sanchez, A.; Canavate Solano, C.; Soto Pazos, E.; Iglesias Alvarez, M.; Gonzalez Macias, C.; Ayala Ortega, C.; Moreno Corral, L.J.; Fernandez Alba, J.J. Hypothyroidism screening during first trimester of pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayerl, S.; Müller, J.; Bauer, R.; Richert, S.; Kassmann, C.M.; Darras, V.M.; Buder, K.; Boelen, A.; Visser, T.J.; Heuer, H. Transporters MCT8 and OATP1C1 maintain murine brain thyroid hormone homeostasis. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 1987–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, B.M.; Knight, B.A.; Hill, A.; Hattersley, A.T.; Vaidya, B. Fetal thyroid hormone level at birth is associated with fetal growth. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, E934–E938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | N = 98 1 |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 33.37 (8.67) |

| Ethnicity, Italian | 65.00 (66.3%) |

| Weight, kg | 66.50 (16.00) |

| Height, cm | 162.00 (7.75) |

| Prepregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 24.98 (5.66) |

| Smoker, yes | 15.00 (15.3%) |

| Weight gain, kg | 13.00 (7.75) |

| Pregnancy duration, weeks | 39.40 (2.10) |

| TSH, mIU/L | 1.415 (1.685) |

| FT3, pmol/L | 3.9 (1.375) |

| FT4, pmol/L | 14.16 (4.07) |

| Characteristic | Beta | 95% CI 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TSH | 28.353 | −34.723, 91.428 | 0.370 |

| Age | 10.123 | −5.640, 25.885 | 0.210 |

| Ethnicity, Italian | −1.414 | −189.210, 186.382 | 0.990 |

| Prepregnancy BMI | 16.751 | −2.032, 35.533 | 0.080 |

| Smoker, yes | −170.987 | −423.018, 81.045 | 0.180 |

| Weight gain | 8.005 | −2.167, 18.178 | 0.120 |

| Pregnancy weeks | 172.027 | 116.027, 228.026 | <0.001 |

| Characteristic | Beta | 95% CI 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| FT3 | −118.901 | −222.942, −14.859 | 0.026 |

| Age | 9.807 | −5.252, 24.866 | 0.200 |

| Ethnicity, Italian | −64.931 | −245.751, 115.890 | 0.480 |

| BMI | 13.252 | −5.394, 31.898 | 0.160 |

| Smoker, yes | −72.055 | −332.014, 187.904 | 0.580 |

| Weight increase | 5.881 | −4.230, 15.993 | 0.250 |

| Pregnancy weeks | 169.890 | 115.165, 224.616 | <0.001 |

| Characteristic | Beta | 95% CI 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| FT4 | −2.388 | −29.993, 25.217 | 0.860 |

| Age | 8.791 | −6.873, 24.455 | 0.270 |

| Ethnicity, Italian | −20.089 | −206.117, 165.939 | 0.830 |

| BMI | 17.218 | −1.615, 36.051 | 0.073 |

| Smoker, yes | −168.546 | −421.704, 84.611 | 0.190 |

| Weight gain | 7.889 | −2.438, 18.217 | 0.130 |

| Pregnancy weeks | 173.149 | 116.956, 229.343 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

La Verde, M.; De Franciscis, P.; Molitierno, R.; Caniglia, F.M.; Fordellone, M.; Braca, E.; Carbone, C.; Varro, C.; Cirillo, P.; Scappaticcio, L.; et al. Thyroid Hormones in Early Pregnancy and Birth Weight: A Retrospective Study. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 542. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13030542

La Verde M, De Franciscis P, Molitierno R, Caniglia FM, Fordellone M, Braca E, Carbone C, Varro C, Cirillo P, Scappaticcio L, et al. Thyroid Hormones in Early Pregnancy and Birth Weight: A Retrospective Study. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(3):542. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13030542

Chicago/Turabian StyleLa Verde, Marco, Pasquale De Franciscis, Rossella Molitierno, Florindo Mario Caniglia, Mario Fordellone, Eleonora Braca, Carla Carbone, Claudia Varro, Paolo Cirillo, Lorenzo Scappaticcio, and et al. 2025. "Thyroid Hormones in Early Pregnancy and Birth Weight: A Retrospective Study" Biomedicines 13, no. 3: 542. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13030542

APA StyleLa Verde, M., De Franciscis, P., Molitierno, R., Caniglia, F. M., Fordellone, M., Braca, E., Carbone, C., Varro, C., Cirillo, P., Scappaticcio, L., & Bellastella, G. (2025). Thyroid Hormones in Early Pregnancy and Birth Weight: A Retrospective Study. Biomedicines, 13(3), 542. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13030542