The Psychosocial Effect of Parental Cancer: Qualitative Interviews with Patients’ Dependent Children

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

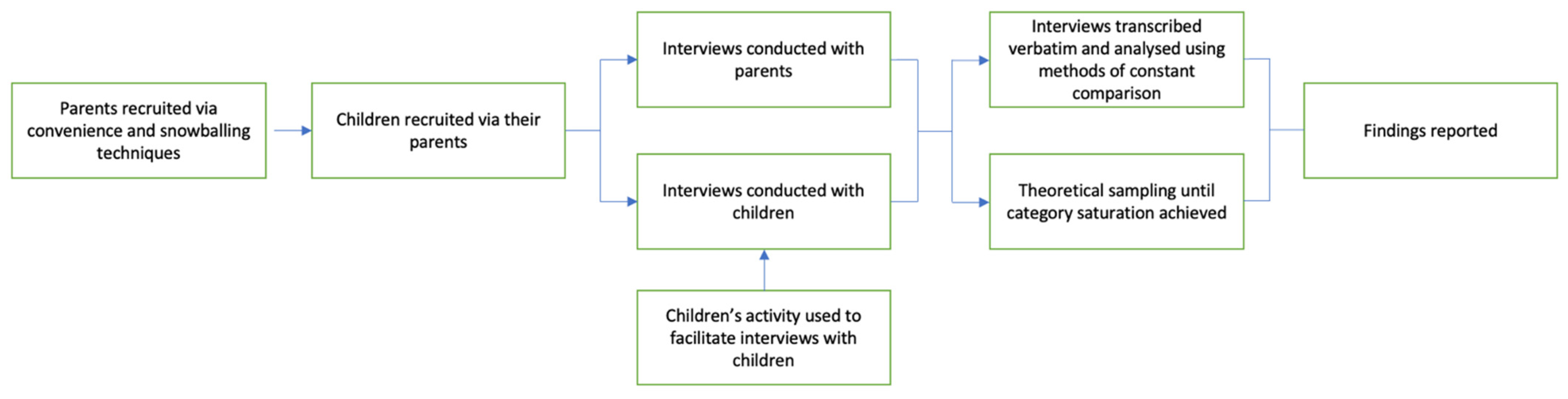

2.1. Design

2.2. Participant Recruitment

Participants

2.3. Interviews

Children’s Activity

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Findings

3.1. Feeling Worried and Distressed

Participant: “In my ‘worries’ I usually write about mummy’s cancer and in the ‘feelings’ I usually write worried, happy, angry and frustrated”.

Interviewer: “Is that how you generally feel?”

Participant: “Yep”.

Interviewer: “You feel worried and frustrated a lot of time?”

Participant: “Yes”.

Interviewer: “When do you feel happy?”

Participant: “When mummy’s okay and she’s doing stuff”(Batari; female: 8.5 years)

“I worry about the dogs dying. I worry about mum dying. I worry about all of my family, really”(Kayla, female: 10 years).

“I just want to go home every day... Because I want to stay with my mummy to make her feel better”.(Arianna; female: 6.5 years).

Interviewer: “How did you deal with that worry?”

Participant: “I don’t think I really dealt with that worry. It sought of just lingered around”.(Lucas; male: 12 years).

3.2. Comprehending Their Parent’s Cancer Diagnosis

“I don’t know about it [cancer]... I just know that cancer is a bit dangerous… Because people that have cancer may die...I don’t really know much about what sort of cancer she had or how she got saved. I just know that she had cancer and she was lucky enough to get saved”.(Indigo; female: 8 years).

Interviewer: “Can you tell me what you know about mum’s cancer?”

Participant: “Brain cancer, kills people”(notably, the parent did not have a brain cancer diagnosis).

Interviewer: “Did someone you know have brain cancer?”.

Participant: “It’s granddad. He died”.(Arianna; female: 6.5 years).

“No. I know that it’s not life-threatening and that it’s dying slowly. It’s minimizing. So, that’s all I want to know”.(Darius; male: 13 years).

Talking about Their Parent’s Cancer Diagnosis

Interviewer: “Do you know anything else about mum’s cancer?”.

Participant: “No”.

Interviewer: “Do you know if she’s getting any medication for it?”.

Participant: “No”.

Interviewer: “Are they giving her anything to make her feel better?”.

Participant: “Yeah. Medicine”.(Arianna, female: 6.5 years).

Participant: “When I look back it, I wished I’d asked more questions… I’d feel a sense of closure if I did ask…”.

Interviewer: “Do you know what you would ask?”.

Participant: “I’m generally unsure of it, I just feel the need to know something”.

Interviewer: “Is it something you can ask mum about?”.

Participant: “It might be, but I’m unsure of how to do this”.(Lucas, male: 12 years).

3.3. Being Disconnected from Their Supports

Participant: “I spent more time with her before she got sick. She’s having another operation to take the bag away and then we’re going to have more time to be with her again”.

Interviewer: “Are you looking forward to that?”.

Participant: “I’ve been waiting for it for 1000 years”(Arianna, female: 6.5 years).

“When she got cancer, she couldn’t do it [cooking] so she just gives us like baked beans or spaghetti”.(Darius, male: 13 years).

“Mummy can’t drive that much so we can’t really go down to (Location A) and (Location B) that much. So, I don’t get to see my family because most of them live in (Location A)”.(Batari, female: 8.5 years).

“I miss my friends because most of them, they are not at home and we’re not going to school”.(Arianna, female: 6.5 years).

“Well, now I can’t exactly go out on walks with the dog because Dad used to come with me and now, he can’t drive me to dancing. I used to do dancing, tap, acro and I started jazz”.(Sarah, female: 11 years).

Participant: “The one that made me happy really, really, really happy was my grandpa and my favourite auntie”.

Interviewer: “In [home country]?”

Participant: “Yep”.

Interviewer: “So, you spent a lot of time with them, did you?”

Participant: “Yep”.(Indigo; female: 8 years).

Interviewer: “When you found out that daddy was sick, and your family moved away, how did you feel then?”

Participant: “Worried... “That’s when Mr. Worry Monster came. Until I made some friends”.(Farrah; female: 7 years).

3.4. Needing Someone to Talk to

“I would ask my Mum, or I could ask my dad. I would ask either one of them or maybe someone who was in the house. If I was with my grandma and granddad, I would ask them as well. I’m comfortable with asking anyone that is older than me, not my friends because they probably wouldn’t know as much as I would”(Sarah; female: 11 years).

Participant: “They all repeated the same thing, ‘if there’s anything you want to tell us, you can tell us…’. I genuinely don’t think that works…this doesn’t always fill the gap”.

Interviewer: “What’s the gap?”.

Participant: “The gap is a feeling of emptiness, teachers saying you can get something off your chest is a feeling that it’s not enough, there’s a void between you and them that doesn’t make it feel like you can talk to them”(Lucas; male: 12 years).

“The therapist only goes for 10 min—she asks questions. I don’t really get a chance to ask”.(Batari; female: 8.5 years).

“I would talk to my friends, but I can’t ask them questions because I don’t think they would understand them”.(Sarah; female: 11 years).

“Sometimes yes, because they would be more likely to understand than some of my friends who have no family problems with that. Although they do try to help me, my actual friends, and they try to understand as much as possible, but sometimes you just can’t understand”(Sarah; female: 11 years).

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Clinical Significance

5. Conclusions

- Cancer patients’ children experience heightened levels of worry and distress at the time of diagnosis, and this continues to affect some children’s psychosocial wellbeing past their parents’ remission and/or bereavement.

- Children feel disconnected from their available support networks, including parents who are often unavailable or pre-occupied, extended family and friends who are difficult to access and perceived unlikely to understand, and health professionals who they do not consider for psychosocial and emotional support.

- Children need help with comprehending their parents’ cancer diagnosis and their associated complex thoughts and emotions, which impacts their capacity to effectively communicate with parents and other adults.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia. Cancer Series no. 119. Cat. No. CAN 123; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Werner-Lin, A.; Biank, N.M. Along the cancer continuum: Integrating therapeutic support and bereavement groups for children and teens of terminally ill cancer patients. J. Fam. Soc. Work 2009, 12, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syse, A.; Aas, G.B.; Loge, J.H. Children and young adults with parents with cancer: A population-based study. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 4, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weaver, K.E.; Rowland, J.H.; Alfano, C.M.; McNeelBa, T.S.M. Parental cancer and the family. Cancer 2010, 116, 4395–4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martini, A.; Morris, J.N.; Jackson, H.M.; Ohan, J.L. The impact of parental cancer on preadolescent children (0–11 years) in Western Australia: A longitudinal population study. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchbinder, M.; Longhofer, J.; McCue, K. Family routines and rituals when a parent has cancer. Fam. Syst. Health. 2009, 27, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Baker, F.; Spillers, R.L.; Wellisch, D.K. Psychological adjustment of cancer caregivers with multiple roles. Psycho-Oncol. 2006, 15, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northouse, L.L.; Mood, D.W.; Montie, J.E.; Sandler, H.M.; Forman, J.D.; Hussain, M.; Pienta, K.; Smith, D.; Sanda, M.G.; Kershaw, T. Living with prostate cancer: Patients’ and spouses’ psychosocial status and quality of life. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 4171–4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, C.; McCaughan, E. Family life when a parent is diagnosed with cancer: Impact of a psychosocial intervention for young children. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2013, 22, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dencker, A.; Rix, B.A.; Bøge, P.; Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, T. A qualitative study of doctors’ and nurses’ barriers to communicating with seriously ill patients about their dependent children. Psycho-Oncol. 2017, 26, 2162–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shands, M.E.; Lewis, F.M. Parents with advanced cancer: Worries about their children’s unspoken concerns. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2020, 38, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizinga, G.A.; Visser, A.; Zelders-Steyn, Y.E.; Teule, J.A.; Reijneveld, S.; Roodbol, P.F. Psychological impact of having a parent with cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, S239–S246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Morris, J.N.; Zajac, I.; Turnbull, D.; Preen, D.; Patterson, P.; Martini, A. A longitudinal investigation of Western Australian families impacted by parental cancer with adolescent and young adult offspring. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health. 2019, 43, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ohan, J.L.; Jackson, H.M.; Bay, S.; Morris, J.N.; Martini, A. How psychosocial interventions meet the needs of children of parents with cancer: A review and critical evaluation. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2020, 29, e13237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, F.; Lewis, F.M. The adolescent’s experience when a parent has advanced cancer: A qualitative inquiry. Palliat. Med. 2015, 29, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huizinga, G.A.; Visser, A.; Van Der Graaf, W.T.A.; Hoekstra, H.J.; Gazendam-Donofrio, S.M.; Hoekstra-Weebers, J.E.H.M. Stress response symptoms in adolescents during the first year after a parent’s cancer diagnosis. Support. Care Cancer 2010, 18, 1421–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jeppesen, E.; Bjelland, I.; Fosså, S.D.; Loge, J.H.; Dahl, A.A. Health-related quality of life in teenagers with a parent with cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 22, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, J.; Turnbull, D.; Preen, D.; Zajac, I.; Martini, A. The psychological, social, and behavioural impact of a parent’s cancer on adolescent and young adult offspring aged 10–24 at time of diagnosis: A systematic review. J. Adolesc. 2018, 65, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, F.; Ferrari, F.; Pravettoni, G. When a parent has cancer: How does it impact on children’s psychosocial functioning? A systematic review. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2018, 27, e12895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, A.; McDonald, F.; Patterson, P.; Dobinson, K.; Allison, K. How does parental cancer affect adolescent and young adult offspring? A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 77, 54–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, S.; Wakefield, C.; Antill, G.; Burns, M.; Patterson, P. Supporting children facing a parent’s cancer diagnosis: A systematic review of children’s psychosocial needs and existing interventions. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2017, 26, e12432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylund-Grenklo, T.; Fürst, C.J.; Nyberg, T.; Steineck, G.; Kreicbergs, U. Unresolved grief and its consequences. A nationwide follow-up of teenage loss of a parent to cancer 6–9 years earlier. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 3095–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoppelbein, L.A.; Greening, L.; Elkin, T.D. Risk of posttraumatic stress symptoms: A comparison of child survivors of pediatric cancer and parental bereavement. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2006, 31, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visser, A.; Huizinga, G.A.; Hoekstra, H.J.; Van Der Graaf, W.T.; Gazendam-Donofrio, S.M.; Hoekstra-Weebers, J.E. Emotional and behavioral problems in children of parents recently diagnosed with cancer: A longitudinal study. Acta Oncol. 2007, 46, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Phillips, F.; Prezio, E.A. Wonders & Worries: Evaluation of a child centered psychosocial intervention for families who have a parent/primary caregiver with cancer. Psycho-Oncol 2016, 26, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.; O’Connor, M.; Halkett, G.K.B. Supporting parents with cancer: Practical factors which challenge nurturing care; (to be submitted); Curtin University: Perth, Western Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pholsena, T.N. Advanced Parental Cancer and Adolescents: A Pilot Study of Parent-Reported Concerns; University of Washington: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Detmar, S.B.; Aaronson, N.K.; Wever, L.D.V.; Muller, M.; Schornagel, J.H. How are you feeling? Who wants to know? Patients’ and Oncologists’ preferences for discussing health-related quality-of-life issues. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 3295–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.; O’Connor, M.; Halkett, G.K.B. The perceived effect of parental cancer on children still living at home: According to oncology health professionals. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2020, 29, e13321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.; O’Connor, M.; Rees, C.; Halkett, G. A systematic review of the current interventions available to support children living with parental cancer. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1812–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, F.M.; Casey, S.M.; Brandt, P.A.; Shands, M.E.; Zahlis, E.H. The Enhancing Connections Program: Pilot study of a cognitive-behavioral intervention for mothers and children affected by breast cancer. Psycho-Oncol 2006, 15, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, F.M.; Brandt, P.A.; Cochrane, B.B.; Griffith, K.A.; Grant, M.; Haase, J.E.; Houldin, A.D.; Post-White, J.; Zahlis, E.H.; Shands, M.E. The Enhancing Connections Program: A six-state randomized clinical trial of a cancer parenting program. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 83, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, K.L. Use your words: Healing communication with children and teens in healthcare settings. Pediatr. Nurs. 2016, 42, 204–205. [Google Scholar]

- Zandt, F. Creative Ways to Help Children Manage Big Feelings: A Therapist’s Guide to Working with Preschool and Primary Children; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A.L. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart-Tufescu, A.; Huynh, E.; Chase, R.; Mignone, J. The Life Story Board: A task-oriented research tool to explore children’s perspectives of well-being. Child Indic. Res. 2019, 12, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akesson, B.; D’Amico, M.; Denov, M.; Khan, F.; Linds, W.; Mitchell, C. ‘Stepping back’ as researchers: Addressing ethics in arts-based approaches to working with working with war-affected children in school and community settings. Educ. Res. Soc. 2014, 3, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Liebman, M.S. Draw and tell: Drawings within the context of child sexual abuse investigations. Arts Psychother. 1999, 26, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M.M. Meta-analysis of studies assessing the efficacy of projective techniques in discriminating child sexual abuse. Child Abus. Negl. 1998, 22, 1151–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Park, S. A Sociocultural Approach to Children’s Perceptions of Death and Loss. Omega 2017, 76, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landreth, G.L. Play Therapy: The Art of the Relationship, 3rd ed.; Taylor and Francis: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (Updated 2018). In The National Health and Medical Research Council, the Australian Research Council and Universities Australia; National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, Australia, 2007.

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis; London: SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L.; Strutzel, E. The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Nurs. Res. 1968, 17, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mays, N.; Pope, C. Qualitative Research in Health Care, 3rd ed.; Blackwell Pub: Malden, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gaab, E.M.; Owens, G.R.; MacLeod, R.D. Caregivers’ estimations of their children’s perceptions of death as a biological concept. Death Stud. 2013, 37, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauel, K.; Simon, A.; Krause-Hebecker, N.; Czimbalmos, A.; Bottomley, A.; Flechtner, H. When a parent has cancer: Challenges to patients, their families and health providers. Expert Rev. Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2012, 12, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner-Lin, A.; Merrill, S.L.; Brandt, A.C. Talking with children about adult-onset hereditary cancer risk: A developmental approach for parents. J. Genet. Couns. 2018, 27, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiss, D.A.; Brewerton, T.D. Adverse childhood experiences and adult obesity: A systematic review of plausible mechanisms and meta-Analysis of cross-sectional studies. Physiol. Behav. 2020, 223, 112964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauken, M.A.; Senneseth, M.; Dyregrov, A.; Dyregrov, K. Anxiety and the quality of life of children living with parental cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2018, 41, E19–E27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugge, K.E.; Helseth, S.; Darbyshire, P. Children’s experiences of participation in a family support program when their parent has incurable cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2008, 31, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christ, G.H.; Siegel, K.; Freund, B.; Langosch, D.; Hendersen, S.; Sperber, D.; Weinstein, L. Impact of parental terminal cancer on latency-age children. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1993, 63, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahlis, E.H. The child’s worries about the mother’s breast cancer: Sources of distress in school-age children. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2001, 28, 1019. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, F.M.; Loggers, E.T.; Phillips, F.; Palacios, R.; Tercyak, K.P.; Griffith, K.A.; Shands, M.E.; Zahlis, E.H.; Alzawad, Z.; Almulla, H.A. Enhancing Connections-Palliative Care: A quasi-experimental pilot feasibility study of a cancer parenting program. J. Palliat. Med. 2019, 23, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krattenmacher, T.; Kühne, F.; Ernst, J.; Bergelt, C.; Romer, G.; Möller, B. Parental cancer: Factors associated with children’s psychosocial adjustment–a systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2012, 72, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemelä, M.; Paananen, R.; Hakko, H.; Merikukka, M.; Gissler, M.; Räsänen, S. The prevalence of children affected by parental cancer and their use of specialized psychiatric services: The 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort study. Int. J. Cancer Res. 2012, 131, 2117–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shallcross, A.J.; Visvanathan, P.D.; McCauley, R.; Clay, A.; Van Dernoot, P.R. The effects of the CLIMB® program on psychobehavioral functioning and emotion regulation in children with a parent or caregiver with cancer: A pilot study. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2016, 34, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, A.R.; Sugerman, D.; Zelov, R. On Belay: Providing connection, support, and empowerment to children who have a parent with cancer. J. Exp. Educ. 2013, 36, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dencker, A.; Murray, S.A.; Mason, B.; Rix, B.A.; Bøge, P.; Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, T. Disrupted biographies and balancing identities: A qualitative study of cancer patients’ communication with healthcare professionals about dependent children. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e12991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landreth, G.L. Therapeutic limit setting in the play therapy relationship. J. Exp. Educ. 2002, 33, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, L.; Dolan, P. The voice of the child in social work assessments: Age-appropriate communication with children. Br. J. Soc. Work 2016, 46, 1191–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth, & New South Wales Commission for Children and Young People (2009). Involving children and young people in research [electronic resource]: A compendium of papers and reflections from a think tank co-hosted by the Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth and the NSW Commission for Children and Young People on 11 November 2008; ARACY and the NSW Commission for Children and Young People: Australia, 2009; ISBN 9781921352485. [Google Scholar]

- Beale, E.A.; Sivesind, D.; Bruera, E. Parents dying of cancer and their children. Palliat. Support. Care 2004, 2, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.; Ristovski-Slijepcevic, S. Metastatic cancer and mothering: Being a mother in the face of a contracted future. Med Anthr. 2011, 30, 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugge, E.K.; Helseth, S.; Darbyshire, P. Parents’ experiences of a Family Support Program when a parent has incurable cancer. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 3480–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.M.; Check, D.K.; Song, M.-K.; Reeder-Hayes, E.K.; Hanson, L.C.; Yopp, J.M.; Rosenstein, D.L.; Mayer, D.K. Parenting while living with advanced cancer: A qualitative study. Palliat. Med. 2016, 31, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Children | Number of Participants | n = 12 |

| Age | Range Mean age (SD) | 5–17 years 9.46 (±3.43) years |

| Gender | Female Male | 58% or n = 7 42% or n = 5 |

| Cultural background | Australian | 75% or n = 9 |

| Indonesian | 17% or n = 2 | |

| Malaysian | 8% or n = 1 | |

| Parent with cancer | Mother | 50% or n = 6 * |

| Father | 50% or n = 6* | |

| Parent’s primary cancer diagnosis ** | Bowel cancer | 2 |

| Brain | 1 | |

| Breast | 1 | |

| Burkitt’s lymphoma | 1 | |

| Lymphoma | 1 | |

| Melanoma | 1 | |

| Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma B cell | 1 | |

| Lung | 1 | |

| Oral | 1 | |

| Stage **(at time of interview) | II | 3 |

| III | 1 | |

| IV | 3 | |

| Not reported/remission/deceased | 3 |

| Number | Question | Prompts |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Can you tell me about your family? | Such as who is in your family? Do you have any pets? |

| 2 | What are the fun things your family enjoy doing together? | Have any of these things changed lately? |

| 3 | Is there anything that you worry about? | |

| 4 | I was hoping you could tell me a little bit about your [mum/dad]. Has [mum/dad] been sick lately? | |

| 5 | What do you call [mum’s/dad’s] sick/sickness? | |

| 6 | Tell me what you know about [mum’s/dad’s] sickness? | |

| 7 | If you have a question about [mum’s/dad’s] sickness, who do you ask or what do you do? | |

| 8 | Is mum and dad OK talking to you about [mum/dad] not being well? | [If yes] Tell me some of the things you talk about with mum and dad? [If no] Would you like to be able to talk to mum and dad about this more? |

| 9 | Are there more things you want to know about [mum’s/dad’s] sickness? | [If yes] Tell me what sort of things? |

| What are some things you do to help you feel better about [mum/dad] not being well? | ||

| Has life been different since [mum/dad] found out [he/she] was not well? | [If yes] Tell me how it has been different? | |

| Are things still the same with your friends, or have they changed? | [If they have changed] Tell me how they have changed? | |

| Are things still the same at school, or have they changed? | [If they have changed] Tell me how they have changed? | |

| Is there someone at school you prefer to talk to about [mum/dad] not being well? | [If yes] Tell me who this person is? | |

| What makes you feel the happiest lately? | [Prompt] Activities? Things? Items? People? | |

| And, what makes you feel unhappy or sad lately? | [Prompt] Activities? Things? Items? People? | |

| If I asked you to do a special activity with mum or dad, and it could be any kind of activity, what would that special activity be? | ||

| If you had a friend that found out their mum or dad was not well in a similar way to your [mum/dad], what would you do to help that friend? | ||

| If you had 3 wishes, what would those wishes be? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alexander, E.S.; O’Connor, M.; Halkett, G.K.B. The Psychosocial Effect of Parental Cancer: Qualitative Interviews with Patients’ Dependent Children. Children 2023, 10, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10010171

Alexander ES, O’Connor M, Halkett GKB. The Psychosocial Effect of Parental Cancer: Qualitative Interviews with Patients’ Dependent Children. Children. 2023; 10(1):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10010171

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlexander, Elise S., Moira O’Connor, and Georgia K. B. Halkett. 2023. "The Psychosocial Effect of Parental Cancer: Qualitative Interviews with Patients’ Dependent Children" Children 10, no. 1: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10010171

APA StyleAlexander, E. S., O’Connor, M., & Halkett, G. K. B. (2023). The Psychosocial Effect of Parental Cancer: Qualitative Interviews with Patients’ Dependent Children. Children, 10(1), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10010171