Sports Practice, Body Image Perception, and Factors Involved in Sporting Activity in Italian Schoolchildren

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design, Procedure, and Study Participants

2.2. Instruments and Variables

2.2.1. Anthropometry

2.2.2. Demography, and Sports Practice

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

| Variables | Total Sample (N = 214) | Boys (N = 119) | Girls (N = 95) | p-Value | Effect Size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric and BI perception indices | ||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.00 ± 3.45 | 18.10 ± 3.27 | 17.88 ± 3.69 | 0.5377 * | 0.002 | |||

| Feel figure | 3.69 ± 1.33 | 3.93 ± 1.27 | 3.38 ± 1.34 | 0.0013 § | 0.219 | |||

| Ideal figure | 3.24 ± 1.25 | 3.58 ± 1.28 | 2.82 ± 1.08 | <0.0001 § | 0.310 | |||

| FID | 0.44 ± 1.33 | 0.35 ± 1.48 | 0.56 ± 1.12 | 0.1493 § | 0.098 | |||

| FAI | −0.34 ± 0.59 | −0.31 ± 0.56 | −0.38 ± 0.62 | 0.3360 § | 0.066 | |||

| Weight status | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||||

| UW | 18 (8.4) | 6 (5.0) | 12 (12.6) | 0.0546 & | 0.165 | |||

| NW | 131 (61.2) | 80 (67.2) | 51 (53.7) | |||||

| OW/O | 65 (30.4) | 33 (27.7) | 32 (33.7) | |||||

| Sports practice | ||||||||

| Yes (N(%)) | 188 (87.9) | 101 (84.9) | 87 (91.6) | 0.1358 & | 0.102 | |||

| Amount (hours/week) | 3.19 ± 2.52 | 3.01 ± 2.11 | 3.41 ± 2.95 | 0.2637 * | 0.006 | |||

| Sports practice (years) | 2.93 ± 2.29 | 2.79 ± 2.21 | 3.11 ± 2.37 | 0.2744 * | 0.006 | |||

| Playing Sports: expectancies of rewards and facilitators | Agree N (%) | Disagree N (%) | Agree N (%) | Disagree N (%) | Agree N (%) | Disagree N (%) | ||

| Makes fun | 208 (97.2) | 6 (2.8) | 116 (97.5) | 3 (2.5) | 92 (96.8) | 3 (3.2) | 0.7792 & | 0.005 |

| Makes health better | 213 (99.5) | 1 (0.5) | 118 (99.2) | 1 (0.8) | 95 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.8726 & | 0.021 |

| Makes thin | 194 (90.7) | 20 (9.3) | 104 (87.4) | 15 (12.6) | 90 (94.7) | 5 (5.3) | 0.0668 & | 0.230 |

| Makes stronger | 209 (97.7) | 5 (2.3) | 117 (98.3) | 2 (1.7) | 92 (96.8) | 3 (3.2) | 0.4772 & | 0.049 |

| Finds support from my parents | 198 (92.5) | 16 (7.5) | 110 (92.4) | 9 (7.6) | 88 (92.6) | 7 (7.4) | 0.9571 & | 0.003 |

| Finds support from my teachers | 172 (72.4) | 42 (27.6) | 95 (69.7) | 24 (20.2) | 77 (75.8) | 18 (18.9) | 0.8232 & | 0.003 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Logan, K.; Cuff, S. Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Organized Sports for Children, Preadolescents, and Adolescents. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20190997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UK Chief Medical Officers’ Physical Activity Guidelines. 2019. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/832868/uk-chief-medical-officers-physical-activity-guidelines.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Zaccagni, L.; Rinaldo, N.; Gualdi-Russo, E. Anthropometric Indicators of Body Image Dissatisfaction and Perception Inconsistency in Young Rhythmic Gymnastics. Asian J. Sports Med. 2019, 10, e87871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, C.; Fitzpatrick, P. Child and adolescent patterns of commuting to school. Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 36, 102404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley Davelaar, C.M. Body Image and its Role in Physical Activity: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2021, 13, e13379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: A pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiium, N.; Säfvenbom, R. Participation in Organized Sports and Self-Organized Physical Activity: Associations with Developmental Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malm, C.; Jakobsson, J.; Isaksson, A. Physical Activity and Sports-Real Health Benefits: A Review with Insight into the Public Health of Sweden. Sports 2019, 7, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Ahmed, K.R.; Hidajat, T.; Edwards, E.J. Examining the Association between Sports Participation and Mental Health of Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 17078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Säfvenbom, R.; Wheaton, B.; Agans, J.P. ‘How can you enjoy sports if you are under control by others?’Self-organized lifestyle sports and youth development. Sport Soc. 2018, 21, 1990–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.E.; Reis, R.S.; Sallis, J.F.; Wells, J.C.; Loos, R.J.; Martin, B.W. Correlates of physical activity: Why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet 2012, 380, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.; Mendonça, G.; Benedetti, T.R.B.; Borges, L.J.; Streit, I.A.; Christofoletti, M.; Silva-Júnior, F.L.E.; Papini, C.B.; Binotto, M.A. Barriers and facilitators of domain-specific physical activity: A systematic review of reviews. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franke, C.M.; Krug, M.M. Perception on facilitators and benefits of participation in body practice groups. Rev. Bras. Cineantropom Desempenho Hum. 2020, 22, e60330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.; Costa, J.; Sarmento, H.; Marques, A.; Farias, C.; Onofre, M.; Valeiro, M.G. Adolescents’ Perspectives on the Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity: An Updated Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, J.; Levin, K.A.; Inchley, J. Socio-environmental influences on physical activity among young people: A qualitative study. Health Educ. Res. 2013, 28, 954–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plenty, S.; Mood, C. Money, peers and parents: Social and economic aspects of inequality in youth wellbeing. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1294–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, D.M.; Murphy, M.; Carlin, A.; Coppinger, T.; Donnelly, A.; Dowd, K.P.; Keating, T.; Murphy, N.; Murtagh, E.; O’Brien, W.; et al. Results From Ireland North and South’s 2016 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. J. Phys. Act. Health 2016, 13 (Suppl. S2), S183–S188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tebar, W.R.; Gil, F.C.S.; Werneck, A.O.; Delfino, L.D.; Santos Silva, D.A.; Christofaro, D.G.D. Sports Participation from Childhood to Adolescence is Associated with Lower Body Dissatisfaction in Boys-A Sex-Specific Analysis. Matern. Child. Health J. 2021, 25, 1465–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerset, S.; Hoare, D.J. Barriers to voluntary participation in sport for children: A systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, J.; Temple, V. A systematic review of dropout from organized sport among children and youth. Eur. Physical. Educ. Rev. 2015, 21, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministero della Pubblica Istruzione. Indicazioni Nazionali per il Curricolo della Scuola Dell’infanzia e del Primo Ciclo D’istruzione. 2012. Available online: https://www.miur.gov.it/documents/20182/51310/DM+254_2012.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Cereda, F. Physical activity and sport in school education: Between the person and the needs for health. Form. Insegn. 2016, 14 (Suppl. S2), 345–356. Available online: https://ojs.pensamultimedia.it/index.php/siref/article/view/2006 (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità, EpiCentro—L’epidemiologia per la Sanità Pubblica. Aspetti Epidemiologici in Italia. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/attivita_fisica/epidemiologia-italia (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità, EpiCentro—L’epidemiologia per la Sanità. Okkio Alla Salute: Indagine Nazionale 2019: I Dati Nazionali. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/okkioallasalute/indagine-2019-dati (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Poulsen, A.A.; Desha, L.; Ziviani, J.; Griffiths, L.; Heaslop, A.; Khan, A.; Leong, G.M. Fundamental movement skills and self-concept of children who are overweight. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2011, 6, e464–e471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richman, E.L.; Shaffer, D.R. If you let me play sports: How might sport participation influence the self-esteem of adolescent females? Psychol. Women Q. 2000, 24, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan, S. Body Image: Understanding Body Dissatisfaction in Men, Women and Children, 3rd ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016; p. 201. [Google Scholar]

- Divecha, C.A.; Simon, M.A.; Asaad, A.A.; Tayyab, H. Body Image Perceptions and Body Image Dissatisfaction among Medical Students in Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2022, 22, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, S.; Murray, S.B.; Bentley, C.; Gratwick-Sarll, K.; Harrison, C.; Mond, J.M. Sex ifferences in quality of life impairment associated with body dissatisfaction in adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollerhed, A.C.; Fransson, J.; Skoog, J.; Garmy, P. Physical Activity Levels, Perceived Body Appearance, and Body Functioning in Relation to Perceived Wellbeing Among Adolescents. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 830913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollerhed, A.-C.; Lilja, E.; Heldt Holmgren, E.; Garmy, P. Subjective health, physical activity, body image and school wellbeing among adolescents in South of Sweden. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunde, C.; Reinholdsson, T.; Skoog, T. Unexcused absence from physical education in elementary school. On the role of autonomous motivation and body image factors. Body Image 2023, 45, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualdi-Russo, E.; Rinaldo, N.; Zaccagni, L. Physical Activity and Body Image Perception in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Bustos, J.G.; Infantes-Paniagua, Á.; Cuevas, R.; Contreras, O.R. Effect of Physical Activity on Self-Concept: Theoretical Model on the Mediation of Body Image and Physical Self-Concept in Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonstroem, R.J.; Morgan, W.P. Exercise and self-esteem: Rationale and model. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1989, 21, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordstar, J.J.; van der Net, J.; Jak, S.; Helders, P.J.; Jongmans, M.J. Global self-esteem, perceived athletic competence, and physical activity in children: A longitudinal cohort study. Psychol. Sport. Exerc. 2016, 22, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Xu, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Lou, X.; Liang, J.; Tao, F. Body image as risk factor for emotional and behavioral problems among Chinese adolescents. BMC Public. Health 2018, 18, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, S.A.; Wertheim, E.H.; Paxton, S.J. Preferences for being muscular and thin in 6-year-old boys. Body Image 2018, 26, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualdi-Russo, E.; Rinaldo, N.; Masotti, S.; Bramanti, B.; Zaccagni, L. Sex Differences in Body Image Perception and Ideals: Analysis of Possible Determinants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras, O.R.; Fernández-Bustos, J.G.; García, L.M.; Palou, P.; Ponseti, J. Relationship in adolescents between physical self-concept and participating in sport. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2010, 19, 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Damiano, S.R.; McLean, S.A.; Nguyen, L.; Yager, Z.; Paxton, S.J. Do we cause harm? Understanding the impact of research with young children about their body image. Body Image 2020, 34, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, C.P.; Telford, R.M.; Telford, R.D.; Olive, L.S. Sport, physical activity and physical education experiences: Associations with functional body image in children. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 45, 101572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTAT (Istituto Nazionale di Statistica). Il Benessere Equo e Sostenibile Dei Territori. Veneto. 2023. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2023/10/sintesi_veneto-BesT.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Città di Monselice. La Dinamica Comunale e Territoriale Degli Insediamenti Produttivi e del Lavoro a Monselice. 2018. Available online: https://www.comune.monselice.padova.it/c028055/po/mostra_news.php?id=1677&area=H (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Lohman, T.G.; Roche, A.F.; Martorell, R. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual; Human Kinetics Books: Champaign, IL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gualdi Russo, E. Metodi Antropometrici: Generalità e principali caratteri antropometrici. In Manuale di Antropologia. Evoluzione e Biodiversità Umana; Sineo, L., Moggi Cecchi, J., Eds.; UTET: Torino, Italy, 2022; pp. 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, T.J.; Bellizzi, M.C.; Flegal, K.M.; Dietz, W.H. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: International survey. BMJ 2000, 320, 1240–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, T.J.; Flegal, K.M.; Nicholls, D.; Jackson, A.A. Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents: International survey. BMJ 2007, 335, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendo-Lázaro, S.; Polo-del-Río, M.I.; Amado-Alonso, D.; Iglesias-Gallego, D.; León-del-Barco, B. Self-Concept in Childhood: The Role of Body Image and Sport Practice. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.E. Body figure perceptions and preferences among preadolescent children. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1991, 10, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertheim, E.H.; Paxton, S.J.; Tilgner, L. Test-retest reliability and construct validity of Contour Drawing Rating Scale scores in a sample of early adolescent girls. Body Image 2004, 1, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitzmann, J.; Warschburger, P. Psychometric Properties of Figure Rating Scales in Children: The Impact of Figure Ordering. J. Pers. Assess. 2020, 102, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualdi-Russo, E.; Manzon, V.S.; Masotti, S.; Toselli, S.; Albertini, A.; Celenza, F.; Zaccagni, L. Weight status and perception of body image in children: The effect of maternal immigrant status. Nutr. J. 2012, 11, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mciza, Z.; Goedecke, J.H.; Steyn, N.P.; Charlton, K.; Puoane, T.; Meltzer, S.; Levitt, N.S.; Lambert, E.V. Development and validation of instruments measuring body image and body weight dissatisfaction in South African mothers and their daughters. Public. Health Nutr. 2005, 8, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaccagni, L.; Masotti, S.; Donati, R.; Mazzoni, G.; Gualdi-Russo, E. Body image and weight perceptions in relation to actual measurements by means of a new index and level of physical activity in Italian university students. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualdi-Russo, E.; Albertini, A.; Argnani, L.; Celenza, F.; Nicolucci, M.; Toselli, S. Weight status and body image perception in Italian children. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2008, 21, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualdi-Russo, E.; Rinaldo, N. Antropometria e percezione dell’immagine corporea. In Manuale di Antropologia. Evoluzione e Biodiversità Umana; Sineo, L., Moggi Cecchi, J., Eds.; UTET: Torino, Italy, 2022; pp. 485–493. [Google Scholar]

- Amo-Setién, F.J.; Leal-Costa, C.; Abajas-Bustillo, R.; González-Lamuño, D.; Redondo-Figuero, C. Factors associated with grip strength among adolescents: An observational study. J. Hand Ther. 2020, 33, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, D.A.; Buchanan, G.M.; Sadehgi-Azar, L.; Peplau, L.A.; Haselton, M.G.; Berezovskaya, A.; Lipinski, R.E. Desiring the muscular ideal: Men’s body satisfaction in the United States, Ukraine, and Ghana. Psychol. Men. Masc. 2007, 8, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.A.; Lalonde, C.E.; Bain, J.L. Body Image Perceptions: Do Gender Differences Exist? Psi. Chi. J. Undergrad. Res. 2010, 15, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaemsiri, S.; Slining, M.M.; Agarwal, S.K. Perceived weight status, overweight diagnosis, and weight control among US adults: The NHANES 2003–2008 Study. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchôa, F.N.M.; Uchôa, N.M.; Daniele, T.M.D.C.; Lustosa, R.P.; Garrido, N.D.; Deana, N.F.; Aranha, Á.C.M.; Alves, N. Influence of the Mass Media and Body Dissatisfaction on the Risk in Adolescents of Developing Eating Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuong, A.T.; Jarman, H.K.; Doley, J.R.; McLean, S.A. Social Media Use and Body Dissatisfaction in Adolescents: The Moderating Role of Thin- and Muscular-Ideal Internalisation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servizio Sanitario Regionale dell’Emilia-Romagna. L’esercizio Fisico Come Strumento di Prevenzione e Trattamento delle Malattie Croniche: L’esperienza dell’ Emilia-Romagna Nella Prescrizione dell’ Attività Fisica. Centro Stampa Giunta—Regione Emilia-Romagna, Bologna, Marzo. 2014. Available online: https://salute.regione.emilia-romagna.it/normativa-e-documentazione/rapporti/contributi/Contributi%2078%20attivita%20fisica%20e%20malattie%20croniche.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Kantanista, A.; Osinski, W.; Borowiec, J.; Tomczak, M.; Krol-Zielinska, M. Body image, BMI, and physical activity in girls and boys aged 14-16 years. Body Image 2015, 15, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldo, N.; Zaccagni, L.; Gualdi-Russo, E. Soccer training programme improved the body composition of pre-adolescent boys and increased their satisfaction with their body image. Acta Paediatr. 2016, 105, e492–e495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedentop, D. Sport Education: Quality PE through Positive Sport Experiences; Human Kinetics Publishers: Champaign, IL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tendinha, R.; Alves, M.D.; Freitas, T.; Appleton, G.; Gonçalves, L.; Ihle, A.; Gouveia, É.R.; Marques, A. Impact of Sports Education Model in Physical Education on Students’ Motivation: A Systematic Review. Children 2021, 8, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maïano, C.; Morin, A.J.; Lanfranchi, M.C.; Therme, P. Body-related sport and exercise motives and disturbed eating attitudes and behaviours in adolescents. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2015, 23, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rullestad, A.; Meland, E.; Mildestvedt, T. Factors Predicting Physical Activity and Sports Participation in Adolescence. J. Environ. Public. Health. 2021, 2021, 9105953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, A.P.; Oudejans, R.R.D.; Bakker, F.C. Dieting and body image in aesthetic sports: A comparison of Dutch female gymnasts and non-aesthetic sport participants. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2007, 8, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, R.; Alarcão, M.; Narciso, I. Aesthetic sports as high-risk contexts for eating disorders–young elite dancers and gymnasts perspectives. Span. J. Psychol. 2012, 15, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrom, S.; Kull, I.; Nilsson, S.; Bergstrom, A. Web-based self-reported height, weight, and body mass index among Swedish adolescents: A validation study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

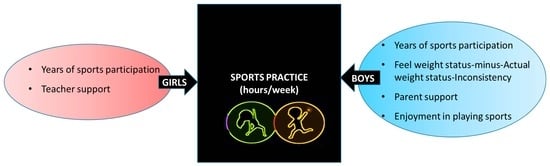

| Predictor | VIF | β | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sports participation (years) | 1.0486 | 0.6076 | 8.6148 | <0.0001 |

| FAI | 1.0109 | 0.1453 | 2.098 | 0.0381 |

| Playing sports finds support from my parents (agree) | 1.2060 | 0.1537 | 2.0317 | 0.0445 |

| Playing sports makes fun (agree) | 1.1715 | 0.1589 | 2.1306 | 0.0353 |

| R2 | 0.4591 | |||

| R2 adjusted | 0.4401 | |||

| p | <0.0001 |

| Predictor | VIF | β | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sports participation (years) | 1.0949 | 0.6082 | 6.8542 | <0.0001 |

| Playing sports finds support from my teachers (agree) | 1.0949 | 0.2010 | 2.2647 | 0.0259 |

| R2 | 0.3384 | |||

| R2 adjusted | 0.3240 | |||

| p | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zaccagni, L.; Rosa, L.; Toselli, S.; Gualdi-Russo, E. Sports Practice, Body Image Perception, and Factors Involved in Sporting Activity in Italian Schoolchildren. Children 2023, 10, 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121850

Zaccagni L, Rosa L, Toselli S, Gualdi-Russo E. Sports Practice, Body Image Perception, and Factors Involved in Sporting Activity in Italian Schoolchildren. Children. 2023; 10(12):1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121850

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaccagni, Luciana, Luca Rosa, Stefania Toselli, and Emanuela Gualdi-Russo. 2023. "Sports Practice, Body Image Perception, and Factors Involved in Sporting Activity in Italian Schoolchildren" Children 10, no. 12: 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121850

APA StyleZaccagni, L., Rosa, L., Toselli, S., & Gualdi-Russo, E. (2023). Sports Practice, Body Image Perception, and Factors Involved in Sporting Activity in Italian Schoolchildren. Children, 10(12), 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121850