Basic Activity of Daily Living Evaluation of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Do-Eat Washy Adaption Preliminary Psychometric Characteristics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials and Design

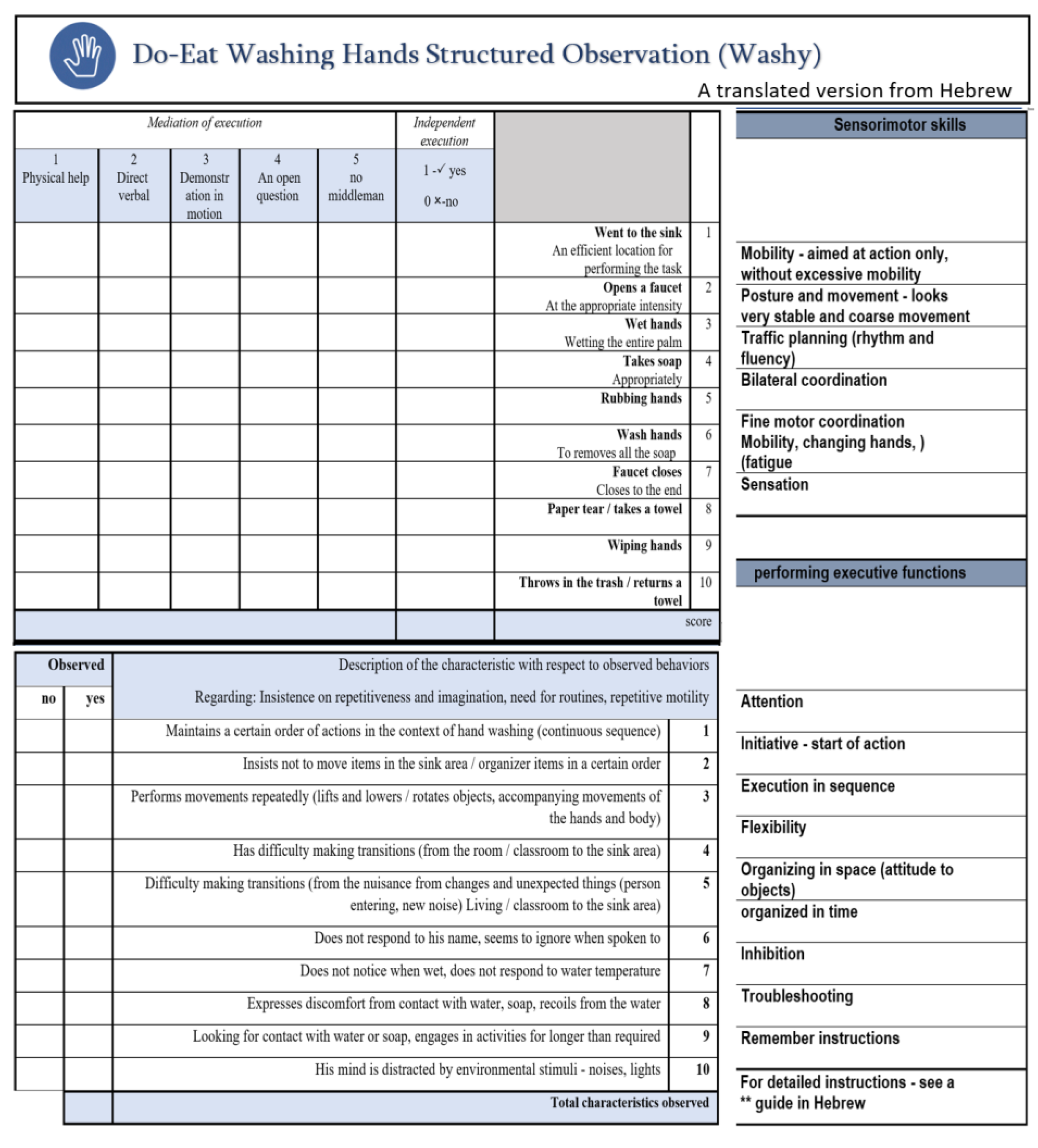

2.2.1. Do-Eat Washy

2.2.2. CARS-2

2.2.3. PICO-Q ASD

2.2.4. PEDI Self-Care Subtest

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Hypothesis A1: Washy Assessment Internal Consistency

3.2. Hypothesis A2: Washy Discriminate Validity

3.3. Hypothesis A3: Washy Convergent Validity

3.4. Hypothesis A4: Washy Concurrent Validity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington DC, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks, D.R.; Wehman, P. Transition from school to adulthood for youth with autism spectrum disorders: Review and recommendations. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2009, 24, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (3rd ed.). Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2014, 68, S1–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golos, A.; Ben-Zur, H.; Chapani, S.I. Participation in preschool activities of children with autistic spectrum disorder and comparison to typically developing children. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 127, 104252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bal, V.H.; Kim, S.H.; Cheong, D.; Lord, C. Daily living skills in individuals with autism spectrum disorder from 2 to 21 years of age. Autism 2015, 19, 774–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jasmin, E.; Couture, M.; McKinley, P.; Reid, G.; Fombonne, E.; Gisel, E. Sensorimotor and daily living skills of preschool children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2009, 39, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan, S.I.; Wieder, S. Engaging Autism: Using the Floortime Approach to Help Children Relate, Think and Communicate; Da Capo Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- LeVesser, P.; Berg, C. Participation patterns in preschool children with an autism spectrum disorder. OTJR Occup. Particip. Health 2011, 31, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, M.; Harel, B.; Fein, D.; Allen, D.; Dunn, M.; Feinstein, C.; Morris, R.; Waterhouse, L.; Rapin, I. Predictors and correlates of adaptive functioning in children with developmental disorders. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2001, 32, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertalik, J.L.; Kubina, R.M. Interventions to improve personal care skills for individuals with autism: A review of the literature. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 4, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, I.-J.; Lin, L.-Y. Relationship between the performance of self-care and visual perception among young children with autism spectrum disorder and typical developing children. Autism Res. 2021, 14, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yela-González, N.; Santamaría-Vázquez, M.; Ortiz-Huerta, J.H. Activities of daily living, playfulness and sensory processing in children with autism spectrum disorder: A Spanish study. Children 2021, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, S.; Coster, W.; Ludlow, L.; Haltiwanger, J.; Andrellos, P. Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI); New England Center Hospitals/PEDI Research Group: Boston, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cossio-Bolanos, M.; Vidal-Espinoza, R.; Alvear-Vasquez, F.; De la Torre Choque, C.; Vidal-Fernandez, N.; Sulla-Torres, J.; Monne de la Peña, R.; Gomez-Campos, R. Validation of a scale to assess activities of daily living at home in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2022, 15, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, S.S.; Cicchetti, D.V.; & Saulnier, C.A. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, 3rd ed.; Pearson: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios-Fernández, S.; Gozalo, M.; García-Gómez, A.; Romero-Ayuso, D.; Hernández-Mocholí, M.Á. A new assessment for activities of daily living in Spanish schoolchildren: A preliminary study of its psychometric properties. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, S.; Waseem, H.; Sadaf, A.; Ashiq, R.; Basit, H.; Rose, S. Daily living tasks affected by sensory and motor problems in children with autism aged 5–12 years. J. Health Med. Nurs. 2021, 92, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlinac, M.E.; Feng, M.C. Assessment of activities of daily living, self-care, and independence. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2016, 31, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fisher, A.G. Assessment of Motor and Process Skills, 5th ed.; Three Star Press: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gonthier, C.; Longuepee, L.; Bouvard, M. Sensory processing in high severity adults with autism spectrum disorder: Distinct sensory profiles and their relationships with behavioral dysfunction. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 3078–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, E.J. Perceptual learning in development: Some basic concepts. Ecol. Psychol. 2000, 12, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, R.; Roberts, J.M.; Hume, K. The Sage Handbook of Autism and Education; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Marco, E.J.; Hinkley, L.B.N.; Hill, S.S.; Nagarajan, S.S. Sensory processing in autism: A review of neurophysiologic findings. Pediatr. Re.s 2011, 69, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, A.G.; Jones, K.B. Assessment of Motor and Process Skills Volume 1: Development, Standardization, and Administration Manual, 7th ed.; Three Star Press: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, C.L.; Zhang, Y.; Whilte, M.R.; Klohr, C.L.; Constantino, J. Motor impairment in sibling pairs concordant and discordant for autism spectrum disorders. Autism 2012, 16, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, S.; Rehman, A.; Waseem, H.; Sadaf, A.; Ashiq, R.; Rose, S.; Basit, H. Effects of sensorimotor problems on the performance of activities of daily living in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Health Med. Nurs. 2020, 70, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whyatt, C.; Craig, C. Sensory-motor problems in autism. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katz, N.; Hartman-Maeir, A. Cognitive Development Across the Lifespan: Development of Cognition and Executive Functions in Children and Adolescents. In Cognition Occupation and Participation Across the Life Span: Models for Intervention in Occupational Therapy; Katz, N., Ed.; AOTA Press: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2018; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, S.J.; Bundy, A.C. Kids Can Be Kids: A Childhood Occupations Approach; FA Davis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, E.L. Evaluating the theory of executive dysfunction in autism. Dev. Rev. 2004, 24, 189–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jurado, M.B.; Rosselli, M. The elusive nature of executive functions: A review of our current understanding. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2007, 17, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panerai, S.; Tasca, D.; Ferri, R.; Genitori D’Arrigo, V.; Elia, M. Executive functions and adaptive behaviour in autism spectrum disorders with and without intellectual disability. Psychiatry J. 2014, 2014, 941809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gardiner, E.; Iarocci, G. Everyday executive function predicts adaptive and internalizing behavior among children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2018, 11, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goffer, A.; Josman, N.; Rosenblum, S. Do–Eat: Performance-Based Assessment Tool for Children. Master’s Thesis, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Josman, N.; Goffer, A.; Rosenblum, S. Development and standardization of the "Do-Eat" Activity of Daily Living Performance test for children. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2010, 64, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Josman, N. Development of the Do–Eat Tool and Performance Outcome Evaluation with Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 72, 7211500018p1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, S.; Engel-Yeger, B. Predicting participation in Children with DCD. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 2014, 1, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenblum, S.; Frisch, C.; Deutsh-Castel, T.; Josman, N. Daily functioning profile of children with attention deficit hyperactive disorder: A pilot study using an ecological assessment. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2015, 25, 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz Zetler, N.; Gal, E.; Engel Yeger, B. Predictors of daily activity performance of children with autism and its association to autism characteristics. Open J. Occup. Ther. 2023, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, I.N.B.; Palomo, S.A.M.; Vicuña, A.M.U.; Bustamante, J.A.D.; Eborde, J.M.E.; Regala, K.A.; Sanchez, A.L.G. Performance-Based Executive Function Instruments Used by Occupational Therapists for Children: A Systematic Review of Measurement Properties. Occup. Ther. Int. 2021, 2021, 6008442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy-Dayan, H.; Rosenblum, S. Participation Characteristics in Self-Care and Activities of Daily Living (ADL) among School-Aged Children with High Severity Compared to Children with High-Functioning Autism and Typical Development. Master’s Thesis, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Luchlan, F.; Elliott, J. The psychological assessment of learning potential. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 71, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schopler, E.; Van Bourgondien, M.; Wellman, J.; Love, S.R. CARS-2: Childhood Autism Rating Scale; Western Psychological Services: Torrence, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, A.; Condillac, R.A.; Freeman, N.L.; Dunn-Geier, J.; Belair, J. Multi-site study of the childhood autism rating scale (CARS) in five clinical groups of young children. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2005, 35, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Shalita, T.; Yochman, A.; Shapiro-Rihtman, T.; Vatine, J.J.; Parush, S. The Participation in Childhood Occupations Questionnaire (PICO-Q): A pilot study. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2009, 29, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, T. Adaptation of the Participation in Childhood Occupation Questionnaire (PICO-Q) for Use in Children with Autism Aged 6–10 Years. Master’s Thesis, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasi, A. Psychological Testing, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | HS (n = 17) | LS (n = 16) | Typical (n = 20) | F/P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | ||||

| Child’s age | 7.52 (0.83) | 8.14 (0.94) | 7.62 (1.26) | 1.68 |

| Mother’s education | 14.52 (2.06) | 14.81 (2.34) | 17.05 (2.01) | ** 7.84 |

| Father’s education | 14.25 (2.79) | 15.64 (3.29) | 16.15 (1.53) | 2.58 |

| Child’s gender | ||||

| Male | 12.00 (70.60) | 11.00 (68.80) | 13.00 (65.00) | |

| Female | 5.00 (29.40) | 5.00 (31.20) | 7.00 (35.00) | ns |

| Socioeconomic level | ||||

| Low | 0 | 1.00 (6.30) | 1.00 (5.00) | |

| Average | 13.00 (76.50) | 9.00 (56.20) | 15.00 (75.00) | |

| Above average | 4.00 (23.50) | 6.00 (37.50) | 4.00 (20.00) | ns |

| Religion | ||||

| Judaism | 15.00 (88.20) | 13.00 (81.30) | 20.00 (100.00) | |

| Christianity | 0 | 2.00 (12.50) | 0 | |

| Other | 2.00 (11.80) | 1.00 (6.30) | 0 | ns |

| School class | ||||

| First grade | 7.00 (41.20) | 6.00 (37.50) | 8.00 (40.00) | |

| Second grade | 7.00 (41.20) | 2.00 (12.50) | 4.00 (20.00) | |

| Third grade | 2.00 (11.80) | 8.00 (50.00) | 6.00 (30.00) | |

| Fourth grade | 1.00 (5.80) | 0 | 2.00 (10.00) | ns |

| ASD in family? | ||||

| Yes | 2.00 (11.80) | 1.00 (6.25) | 1.00 (5.00) | |

| No | 15.00 (88.20) | 15.00 (93.75) | 19.00 (95.00) | ns |

| Variable | HS-ASD (N = 17) | LS-ASD (N = 16) | Typical (N = 20) | F(2,49) | ηp² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | |||||

| Washy performance | |||||

| Total score | 33.82 (11.01) | 56.68 (4.64) | 59.80 (0.69) | *** 66.77 | 0.73 |

| Independence | 5.17 (1.87) | 9.31 (1.01) | 10.00 | *** 72.66 | 0.75 |

| Assistance | 28.64 (9.47) | 47.37 (3.98) | 49.80 (0.69) | *** 59.94 | 0.71 |

| Washy skills | |||||

| Sensorimotor | 2.82 (0.85) | 4.49 (0.43) | 4.83 (0.18) | *** 55.76 | 0.69 |

| Executive function | 3.17 (0.73) | 4.55 (0.33) | 4.86 (0.21) | *** 55.38 | 0.69 |

| No. characteristics | 1.88 (0.92) | 1.00 (0.96) | 0.05 (0.22) | *** 17.91 | 0.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Levy-Dayan, H.; Josman, N.; Rosenblum, S. Basic Activity of Daily Living Evaluation of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Do-Eat Washy Adaption Preliminary Psychometric Characteristics. Children 2023, 10, 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030514

Levy-Dayan H, Josman N, Rosenblum S. Basic Activity of Daily Living Evaluation of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Do-Eat Washy Adaption Preliminary Psychometric Characteristics. Children. 2023; 10(3):514. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030514

Chicago/Turabian StyleLevy-Dayan, Hana, Naomi Josman, and Sara Rosenblum. 2023. "Basic Activity of Daily Living Evaluation of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Do-Eat Washy Adaption Preliminary Psychometric Characteristics" Children 10, no. 3: 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030514