Personal and Social Responsibility Model: Differences According to Educational Stage in Motivation, Basic Psychological Needs, Satisfaction, and Responsibility

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.4. Procedure

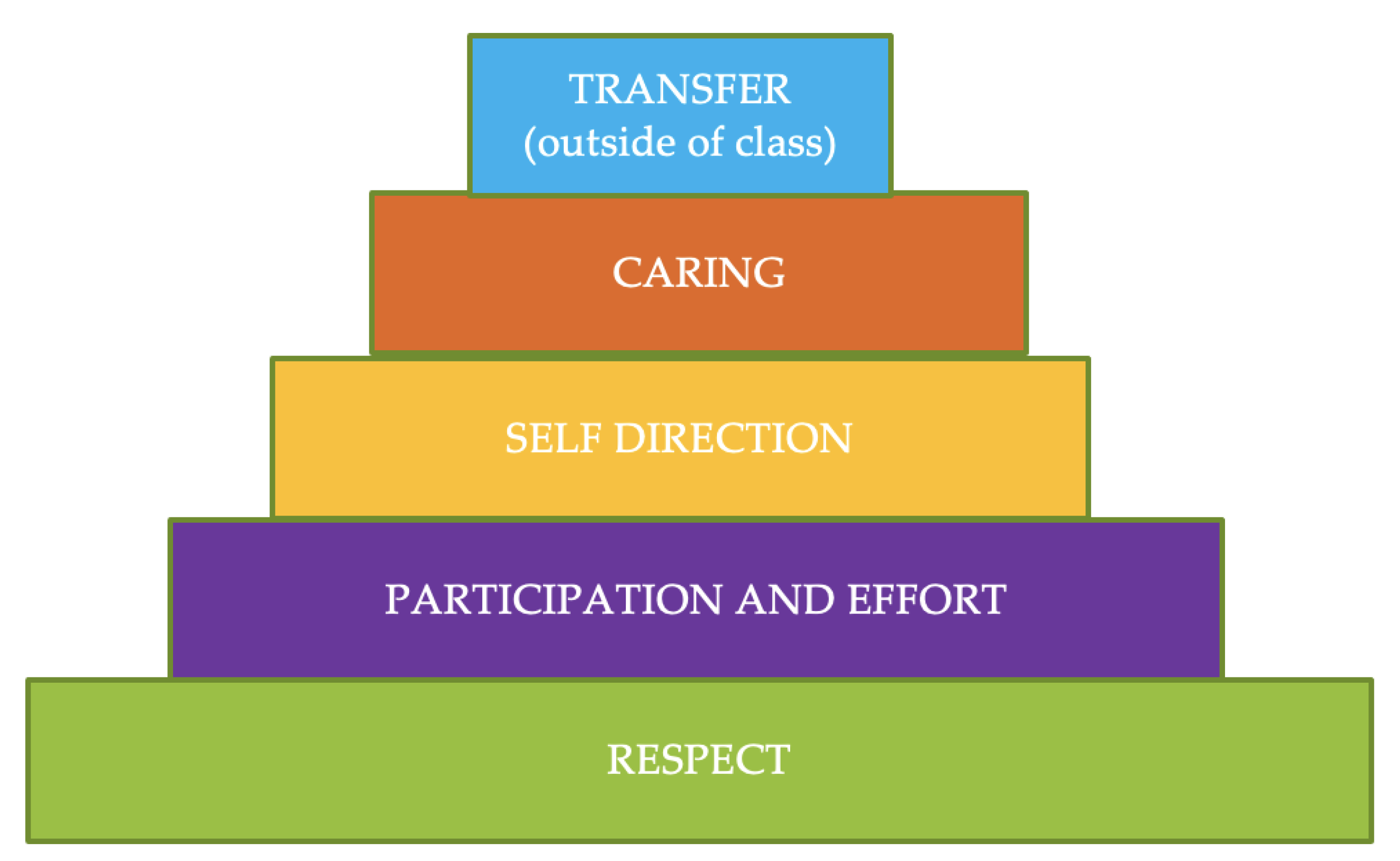

2.4.1. Personal and Social Responsibility Model

2.4.2. Implementation Fidelity

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Values and Correlations

3.2. Results of the Intervention

3.3. Differences in the Experimental Group According to the Educational Stage

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Royal Decree 157/2022, of March 1, Which Establishes the Organization and Minimum Teaching of Primary Education. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2022/03/01/157/con (accessed on 22 January 2023).

- Royal Decree 217/2022, of March 29, Which Establishes the Organization and Minimum Teaching of Compulsory Secondary Education. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2022/03/29/217/con (accessed on 22 January 2023).

- Organic Law 3/2020, of December 29, Which Modifies Organic Law 2/2006, of May 3, on Education. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2020/12/29/3 (accessed on 22 January 2023).

- Garcia-Castejon, G.; Camerino, O.; Castaner, M.; Manzano-Sanchez, D.; Jimenez-Parra, J.F.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Implementation of a hybrid educational program between the model of personal and social responsibility (TPSR) and the teaching games for understanding (TGfU) in physical education and its effects on health: An approach based on mixed methods. Children 2021, 8, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Blanco, M. Self-concept and school motivation: A bibliographic review. Infad J. 2017, 6, 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Hortigüela, D.; Pérez, A.; Calderón, A. Effect of the teaching model on the physical self-concept of students in physical education. Retos 2016, 30, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Implementation of a model-based program to promote personal and social responsibility and its effects on motivation, prosocial behaviors, violence and classroom climate in primary and secondary education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manzano-Sánchez, D. Physical education classes and responsibility: The importance of being responsible in motivational and psychosocial variables. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Parra, J.F.; Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Camerino, O.; Prat, Q.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Effects of a hybrid program of active breaks and responsibility on the behavior of primary students: A mixed methods study. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Gómez-Marmol, A.; Jiménez-Parra, J.F.; Gil Bohorquez, I.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Motivational profiles and their relationship with responsibility, school social climate and resilience in high school students. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Ocana-Salas, B.; Gómez-Marmol, A.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Relationship between school violence, sports personship and personal and social responsibility in students. Apunts 2020, 139, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Marmol, A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Valero-Valenzuela, A.; de la Cruz-Sánchez, E. Perceived violence, sociomoral attitudes and behaviors in school contexts. J. Hu. Sport. Exerc. 2018, 13, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carrasco, C.; Alarcón, R.; Trianes, M.V. Efficacy of a psychoeducational intervention based on the social climate, perceived violence and sociometrics in primary school students. Rev. Psychodidact. 2015, 29, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pedreño, N.B.; Férriz-Morel, R.; Rivas, S.; Almagro, B.; Sáenz-López, P.; Cervelló, E.; Moreno-Murcia, J.A. Sport commitment in adolescent soccer players. Motricidade 2015, 11, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chang, Y.K.; Chen, S.; Tu, K.W.; Chi, L.K. Effect of autonomy support on self-determined motivation in elementary physical education. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2016, 15, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Escartí, A.; Gutiérrez, M.; Pascual, C. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Personal and Social Responsibility Questionnaire in physical education contexts. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2011, 20, 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, O.; Kim, Y.; Kim, B. Relations of perception of responsibility to intrinsic motivation and physical activity among Korean middle school students. Percept. Mot. Skills 2012, 115, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Valero-Valenzuela, A.; Conde-Sánchez, A.; Chen, M.-Y. Applying the Personal and Social Responsibility Model-Based Program: Differences according to gender between basic psychological needs, motivation, life satisfaction and intention to be physically active. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Shen, H.; Belhaidas, M.B.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Yan, J. The relationship between physical fitness and perceived well-being, motivation, and enjoyment in chinese adolescents during physical education: A preliminary cross-sectional study. Children 2023, 10, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory in health care and its relations to motivational interviewing: A few comments. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic-dialectical perspective. In Handbook of Self-Determination Research; Deci, E.L., Ryan, R.M., Eds.; University of Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.L.; Bennie, A.; Vasconcellos, D.; Cinelli, R.; Hilland, T.; Owen, K.B.; Lonsdale, C. Self-determination theory in physical education: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 99, 103247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J. Toward a hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 29, 271–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Barrero, J.A.; Valero-Valenzuela, A.; Belando-Pedreño, N. The model of personal and social responsibility. Study variables associated with its implementation. EmásF 2017, 49, 60–77. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Murcia, J.A.; Huéscar, E.; Cervelló, E. Prediction of adolescents doing physical activity after completing secondary education. Span. J. Psychol. 2013, 15, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Chen, R. Psychological needs satisfaction, self-determined motivation, and physical activity of students in physical education: Comparison across gender and school levels. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2022, 22, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, F.; Neves, R.; Parker, M. Future pathways in implementing the teaching personal and social responsibility model in Spain and Portugal. Retos 2020, 38, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellison, D. Goals and Strategies for Teaching Physical Education; Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc.: Champaign, IL, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J.; Wright, P. Social and emotional learning policies and physical education. Strategies 2014, 27, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escartí, A.; Pascual, C.; Gutiérrez, M. Personal and Social Responsibility Through Physical Education and Sport; Grade: Barcelona, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Gómez-Marmol, A.; Valero, A.; De la Cruz, E. Implementation of a program to improve personal and social responsibility in physical education lessons. Mot. Eur. J. Hum. Mov. 2013, 30, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, C.; Kendellen, K.; Forneris, T. Moving beyond the gym exploring life skill transfer within a female physical activity based life skills program. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2016, 28, 274–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Valenzuela, A.; López, G.; Moreno-Murcia, J.A.; Manzano-Sánchez, D. From students’ personal and social responsibility to autonomy in physical education classes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Merino-Barrero, J.A.; Valero-Valenzuela, A.; Pedreño, N.B.; Fernandez-Río, J. Impact of a sustained TPSR program on students’ responsibility, motivation, sportsmanship, and intention to be physically active. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2019, 39, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escartí, A.; Llopis-Goig, R.; Wright, P. Assessing the implementation fidelity of school-based teaching personal and social responsibility program in physical education and other subject areas. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2017, 37, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Río, J.; Menéndez-Santurio, J.I. Teachers and students’ perceptions of hybrid sport education and teaching for personal and social responsibility learning unit. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2017, 36, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; García-Arjona, N. The Responsibility Model: Development of psychosocial aspects in socially disadvantaged youth through physical activity and sport. Rev. Psychol. Educ. 2011, 6, 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Valero-Valenzuela, A.; Camerino, O.; Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Prat, Q.; Castañer, M. Enhancing learner motivation and classroom social climate: A mixed methods approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menéndez-Santurio, J.I.; Fernández-Río, J. Violence, responsibility, friendship and basic psychological needs: Effects of a sports education and personal and social responsibility program. Rev. Psychodidact. 2016, 21, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Llopis-Goig, R.; Escartí, A.; Pascual, C.; Gutiérrez, M.; Marín, D. Strengths, difficulties and aspects susceptible for improvement in the application of a program of personal and social responsibility in physical education. An evaluation based on the perceptions of its implementers. Cult. Educ. 2011, 23, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ordas, R.; Well, P.; Grao-Cruces, A. Effects on aggression and social responsibility by teaching personal and social responsibility during physical education. J. Phys. Educ. Sport. 2020, 20, 1832–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.; Pan, M.; Shang, I.; Hsiao, C. The Influence of Integrating Moral Disengagement Minimization Strategies into Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility on Student Positive and Misbehaviors in Physical Education. SAGE Open 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavão, I.; Santos, F.; Wright, P.M.; Gonçalves, F. Implementing the teaching personal and social responsibility model within preschool education: Strengths, challenges and strategies. Curric. Stud. Health Phys. Educ. 2019, 10, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.H.; Huang, C.H.; Lee, I.S.; Hsu, W.T. Comparison of learning effects of merging TPSR respectively with sport education and traditional teaching model in high school physical education classes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chunoh, W.E.I.; Ronghai, S.U.; Maochou, H.S.U. Effects of TPSR integrated sport education model on football lesson students’ responsibility and exercise self-efficacy. Rev. De Cercet. Si Interv. Soc. 2020, 71, 126–136. [Google Scholar]

- Montero, I.; León, O. Classification and description of research methodologies in Psychology. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2002, 2, 503–508. [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Blais, M.R.; Brière, N.M.; Pelletier, L.G. Construction and validation of the échelle de motivation en éducation (EME). Can. J. Behav. Sci. 1989, 21, 323–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Núñez, J.L.; Martín-Albo, J.; Navarro, J.G. Validity of the Spanish version of the Échelle de Motivation in Education. Psychothema 2005, 17, 344–349. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, P.; West, S.; Finch, F. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psycho. Methods 1996, 1, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wright, P.; Rukavina, P.; Pickering, M. Measuring students’ perceptions of personal and social responsibility and the relationship to intrinsic motivation in urban physical education. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 2008, 27, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Murcia, J.A.; Gonzalez, D.; Chillon, M.; Parra, N. Adaptation to physical education of the scale of basic psychological needs in the exercise. Rev. Mex. Psych. 2008, 25, 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Murcia, J.A.; Marzo, J.C.; Martínez-Galindo, C.; Marín, L.C. Validation of psychological need satisfaction in exercise scale and the behavioral regulation in sport questionnaire to the Spanish context. RICYDE. Int. J. Sport Sci. 2012, 7, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellison, D. Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility through Physical Activity; Human Kinetics Publishers Inc.: Windsor, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Conte-Marín, L.; Gómez-López, M.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Applying the personal and social responsibility model as a school-wide project in all participants: Teachers’ views. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Escartí, A.; Gutiérrez, M.; Pascual, C.; Wright, P. Observation of the strategies used by physical education teachers to teach personal and social responsibility. Rev. De Psicol. Del Deporte 2013, 22, 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Richardson, N. Research review/teacher learning: What matters. Educ. Leadersh. 2009, 66, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Coulson, C.L.; Irwin, C.C.; Wright, P.M. Applying Hellison’s responsibility model in a youth residential treatment facility: A practical inquiry project. Ágora 2012, 14, 38–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill, M.A.; Templin, T.J.; Wright, P.M. Implementation and outcomes of a responsibility-based continuing professional development protocol in physical education. Sport Educ. Soc. 2015, 20, 398–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Eribaum Associates Publishers: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, T.C.; Laborda, J.; Álvarez, A.L. Physical education and social relations in primary education. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 2, 269–282. [Google Scholar]

- Melero-Cañas, D.; Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Navarro-Ardoy, D.; Morales-Baños, V.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. The Seneb’s Enigma: Impact of a hybrid personal and social responsibility and gamification model-based practice on motivation and healthy habits in physical education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P.; González, A.J.; de Lima, M.P.; Faleiro, J.; Preto, L. Positive development based on the Teaching of Personal and Social Responsibility: An intervention program with institutionalized youngsters. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 792224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreres-Ponsoda, F.; Escartí, A.; Jiménez-Olmedo, J.M.; Cortell-Tormo, J.M. Effects of a Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility Model intervention in competitive youth sport. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 624018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Víllora, S.; Gospel, E.; Sierra-Díaz, J.; Fernández-Río, J. Hybridizing pedagogical models: A systematic review. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2018, 25, 1056–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Sánchez, D. Differences between psychological aspects in primary education and secondary education. Motivation, basic psychological needs, responsibility, classroom climate, prosocial and antisocial behaviors and violence. Espiral 2021, 14, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-González, M. Developing Emotional Intelligence through Physical Education: A Systematic Review. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | Ran | S | k | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Knowledge_M | 5.57 | 1.17 | 1-7 | −0.949 | 0.61 | 0.760 ** | 0.759 ** | 0.584 ** | 0.605 ** | 0.343 ** | −0.205 ** | 0.583 ** | 0.520 ** | 0.504 ** | 0.594 ** | 0.489 ** | 0.677 ** | 0.655 ** |

| 2 | Accomplish_M | 4.79 | 1.32 | 1-7 | −0.469 | −0.211 | 1 | 0.654 ** | 0.513 ** | 0.573 ** | 0.248 ** | −0.239 ** | 0.633 ** | 0.461 ** | 0.484 ** | 0.567 ** | 0.462 ** | 0.680 ** | 0.647 ** |

| 3 | Experience_M | 5.55 | 1.24 | 1-7 | −0.855 | 0.176 | 1 | 0.597 ** | 0.722 ** | 0.444 ** | −0.244 ** | 0.471 ** | 0.509 ** | 0.454 ** | 0.566 ** | 0.455 ** | 0.652 ** | 0.581 ** | |

| 4 | Identified_R | 5.66 | 1.07 | 1-7 | −0.741 | 0.198 | 1 | 0.506 ** | 0.549 ** | −0.334 ** | 0.406 ** | 0.425 ** | 0.384 ** | 0.475 ** | 0.414 ** | 0.682 ** | 0.493 ** | ||

| 5 | Introjected_R | 5.49 | 1.17 | 1-7 | −0.788 | 0.126 | 1 | 0.457 ** | −0.125 * | 0.440 ** | 0.409 ** | 0.352 ** | 0.453 ** | 0.360 ** | 0.404 ** | 0.488 ** | |||

| 6 | External_R | 5.89 | 1.07 | 1-7 | −1018 | 0.589 | 1 | −0.146 ** | 0.224 ** | 0.228 ** | 0.209 ** | 0.225 ** | 0.207 ** | 0.250 ** | 0.268 ** | ||||

| 7 | Amotivation | 1.76 | 1.17 | 1-5 | 1.739 | 2.408 | 1 | −0.135 ** | −0.242 ** | −0.218 ** | −0.384 ** | −0.305 ** | −0.801 ** | −0.238 ** | |||||

| 8 | Autonomy | 3.52 | 0.8 | 1-5 | −0.237 | −0.055 | 1 | 0.560 ** | 0.463 ** | 0.544 ** | 0.429 ** | 0.455 ** | 0.835 ** | ||||||

| 9 | Competence | 3.88 | 0.65 | 1-5 | −0.29 | −0.433 | 1 | 0.504 ** | 0.554 ** | 0.513 ** | 0.485 ** | 0.816 ** | |||||||

| 10 | Relationship | 4.18 | 0.78 | 1-5 | −1.138 | 1.242 | 1 | 0.542 ** | 0.551 ** | 0.461 ** | 0.808 ** | ||||||||

| 11 | Personal_Res | 5.21 | 0.73 | 1-6 | −1.309 | 1.937 | 1 | 0.672 ** | 0.628 ** | 0.666 ** | |||||||||

| 12 | Social_Res | 5.22 | 0.64 | 1-6 | −0.897 | 0.401 | 1 | 0.513 ** | 0.605 ** | ||||||||||

| 13 | SDI | 7.06 | 3.9 | // | −0.917 | 0.351 | 1 | 0.568 ** | |||||||||||

| 14 | BPNs | 3.86 | 0.61 | 1-5 | −0.6 | 0.368 | 1 |

| Control | Experimental | Intergroup differences | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | p-Value | d-Cohen | Mean | SD | p-Value | d-Cohen | p-Value | d-Cohen | ||

| Knowledge_M | pre-test | 5.23 | 1.26 | 0.066 | −0.05 | 5.87 | 0.99 | 0.003 ** | 0.18 | 0.001 ** | 0.57 |

| post test | 5.17 | 1.28 | 6.05 | 0.97 | 0.001 ** | 0.90 | |||||

| Accomplish_M | pre-test | 4.41 | 1.32 | 0.639 | −0.02 | 5.13 | 1.23 | 0.013 ** | 0.19 | 0.001 ** | 0.56 |

| post test | 4.39 | 1.3 | 5.34 | 1.15 | 0.001 ** | 0.80 | |||||

| Experience_M | pre-test | 5.22 | 1.34 | 0.435 | −0.02 | 5.85 | 1.06 | 0.001 ** | 0.24 | 0.001 ** | 0.53 |

| post test | 5.19 | 1.38 | 6.09 | 0.97 | 0.001 ** | 0.89 | |||||

| Identified_R | pre-test | 5.49 | 1.12 | 0.220 | −0.04 | 5.81 | 1 | 0.001 ** | 0.24 | 0.003 ** | 0.30 |

| post test | 5.45 | 1.15 | 6.05 | 0.97 | 0.001 ** | 0.61 | |||||

| Introjected_R | pre-test | 5.3 | 1.23 | 0.889 | 0.04 | 5.66 | 1.08 | 0.001 ** | 0.07 | 0.004 ** | 0.31 |

| post test | 5.35 | 1.28 | 5.74 | 1.09 | 0.002 ** | 0.36 | |||||

| External_R | pre-test | 5.86 | 1.07 | 0.273 | −0.01 | 5.91 | 1.08 | 0.381 | 0.01 | 0.701 | 0.05 |

| post test | 5.85 | 1.03 | 5.92 | 1.08 | 0.330 | 0.06 | |||||

| Amotivation | pre-test | 2.05 | 1.29 | 0.418 | −0.05 | 1.5 | 0.99 | 0.007 ** | −0.24 | 0.000 ** | −0.48 |

| post test | 1.99 | 1.25 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.000 ** | −0.85 | |||||

| Autonomy | pre-test | 3.44 | 0.79 | 0.178 | 0.01 | 3.59 | 0.8 | 0.001 ** | 0.31 | 0.019 * | −0.19 |

| post test | 3.45 | 0.85 | 3.83 | 0.74 | 0.001 ** | −0.49 | |||||

| Competence | pre-test | 3.74 | 0.67 | 0.480 | −0.07 | 4.01 | 0.6 | 0.001 ** | 0.47 | 0.001 ** | 0.43 |

| post test | 3.69 | 0.77 | 4.28 | 0.55 | 0.001 ** | 1.03 | |||||

| Relationship | pre-test | 3.96 | 0.86 | 0.131 | −0.05 | 4.36 | 0.63 | 0.553 | 0.1 | 0.000 ** | 0.54 |

| post test | 3.92 | 0.84 | 4.42 | 0.61 | 0.001 ** | 0.81 | |||||

| Personal_Resp | pre-test | 5.00 | 0.81 | 0.063 | −0.04 | 5.40 | 0.6 | 0.210 | 0.24 | 0.001 ** | 0.57 |

| post test | 4.97 | 0.83 | 5.54 | 0.59 | 0.001 ** | 0.96 | |||||

| Social_Resp | pre-test | 5.04 | 0.7 | 0.692 | −0.01 | 5.39 | 0.53 | 0.001 ** | 0.20 | 0.001 ** | 0.57 |

| post test | 5.03 | 0.71 | 5.5 | 0.57 | 0.001 ** | 0.85 | |||||

| SDI | pre-test | 5.68 | 4.14 | 0.905 | 0.00 | 8.27 | 3.23 | 0.001 ** | 0.34 | 0.001 ** | 0.70 |

| post test | 5.70 | 4.11 | 9.28 | 2.78 | 0.001 ** | 1.19 | |||||

| BPNs | pre-test | 3.71 | 0.64 | 0.116 | −0.03 | 3.99 | 0.55 | 0.002 * | 0.33 | 0.001 ** | 0.47 |

| post test | 3.69 | 0.7 | 4.17 | 0.51 | 0.001 ** | 0.91 | |||||

| Elementary School | Secondary School | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | p-Value | d-Cohen | |

| Knowledge_Motivation | 5.95 | 0.87 | 5.61 | 1.28 | 0.201 | −0.31 |

| Accomplish_Motivation | 5.20 | 1.16 | 4.91 | 1.41 | 0.233 | −0.22 |

| Experience_Motivation | 5.98 | 0.97 | 5.42 | 1.23 | 0.004 ** | −0.50 |

| Identified_Regulation | 5.88 | 1.01 | 5.6 | 0.92 | 0.022 * | −0.29 |

| Introjected_Regulation | 5.75 | 1.03 | 5.36 | 1.19 | 0.037 * | −0.35 |

| External_Regulation | 5.92 | 1.09 | 5.85 | 1.05 | 0.625 | −0.07 |

| Amotivation | 1.49 | 0.96 | 1.52 | 1.09 | 0.812 | 0.03 |

| Autonomy | 3.60 | 0.79 | 3.55 | 0.86 | 0.735 | −0.06 |

| Competece | 4.07 | 0.55 | 3.81 | 0.71 | 0.014 * | −0.41 |

| Relationship | 4.44 | 0.55 | 4.12 | 0.82 | 0.019 * | −0.45 |

| Personal_Responsibility | 5.47 | 0.49 | 5.18 | 0.83 | 0.098 | −0.42 |

| Social_Responsibility | 5.44 | 0.5 | 5.23 | 0.61 | 0.031 * | −0.37 |

| SDI | 8.48 | 3.08 | 7.58 | 3.63 | 0.056 | −0.27 |

| BPNs | 4.04 | 0.5 | 3.83 | 0.67 | 0.122 | −0.35 |

| Elementary School | Secondary School | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | p-Value | d-Cohen | |

| Knowledge_Motivation | 6.08 | 0.96 | 5.98 | 1.02 | 0.659 | −0.10 |

| Accomplish_Motivation | 5.42 | 1.08 | 5.15 | 1.33 | 0.255 | −0.22 |

| Experience_Motivation | 6.19 | 0.9 | 5.78 | 1.11 | 0.014* | −0.40 |

| Identified_Regulation | 6.06 | 0.97 | 6.00 | 0.98 | 0.613 | −0.06 |

| Introjected_Regulation | 5.71 | 1.08 | 5.85 | 1.11 | 0.325 | 0.13 |

| External_Regulation | 5.82 | 1.15 | 6.26 | 0.72 | 0.021 * | 0.47 |

| Amotivation | 1.25 | 0.54 | 1.45 | 0.74 | 0.025 * | 0.31 |

| Autonomy | 3.80 | 0.71 | 3.92 | 0.85 | 0.192 | 0.15 |

| Competence | 4.28 | 0.51 | 4.26 | 0.67 | 0.721 | −0.03 |

| Relationship | 4.44 | 0.6 | 4.33 | 0.73 | 0.458 | −0.16 |

| Personal_Responsibility | 5.62 | 0.43 | 5.29 | 0.89 | 0.06 ** | −0.46 |

| Social_Responsibility | 5.55 | 0.48 | 5.33 | 0.77 | 0.137 | −0.34 |

| SDI | 9.58 | 2.55 | 8.31 | 3.28 | 0.015 * | −0.43 |

| BPNs | 4.17 | 0.47 | 4.17 | 0.62 | 0.626 | 0.00 |

| Elementary School | Secondary School | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | p-Value | d-Cohen | M | SD | p-Value | d-Cohen | ||

| Knowledge_M | pre-test | 5.92 | 0.91 | 0.008 ** | 0.06 | 5.27 | 1.27 | 0.121 | 0.06 |

| post test | 5.98 | 1.05 | 5.35 | 1.26 | |||||

| Accomplish_M | pre-test | 5.20 | 1.20 | 0.016 * | 0.13 | 4.46 | 1.32 | 0.462 | 0.04 |

| post test | 5.35 | 1.13 | 4.51 | 1.33 | |||||

| Experience_M | pre-test | 5.92 | 1.02 | 0.001 ** | 0.20 | 5.24 | 1.32 | 0.075 | 0.05 |

| post test | 6.11 | 1.00 | 5.30 | 1.34 | |||||

| Identified_R | pre-test | 5.87 | 1.00 | 0.012 * | 0.15 | 5.48 | 1.09 | 0.008 ** | 0.07 |

| post test | 6.02 | 0.97 | 5.56 | 1.16 | |||||

| Introjected_R | pre-test | 5.66 | 1.10 | 0.609 | −0.01 | 5.35 | 1.21 | 0.017 * | 0.10 |

| post test | 5.65 | 1.15 | 5.47 | 1.23 | |||||

| External_R | pre-test | 5.85 | 1.15 | 0.511 | −0.04 | 5.91 | 1.00 | 0.002 ** | 0.05 |

| post test | 5.80 | 1.16 | 5.96 | 0.95 | |||||

| Amotivation | pre-test | 1.49 | 0.96 | 0.002 ** | −0.31 | 1.98 | 1.29 | 0.914 | −0.03 |

| post test | 1.25 | 0.55 | 1.94 | 1.20 | |||||

| Autonomy | pre-test | 3.61 | 0.77 | 0.007 ** | 0.24 | 3.44 | 0.82 | 0.008 ** | 0.11 |

| post test | 3.79 | 0.75 | 3.53 | 0.85 | |||||

| Competece | pre-test | 4.06 | 0.57 | 0.001 ** | 0.36 | 3.74 | 0.68 | 0.001 ** | 0.05 |

| post test | 4.26 | 0.54 | 3.78 | 0.79 | |||||

| Relationship | pre-test | 4.43 | 0.56 | 0.851 | −0.02 | 3.96 | 0.86 | 0.145 | 0.02 |

| post test | 4.42 | 0.62 | 3.98 | 0.85 | |||||

| Personal_Resp | pre-test | 5.46 | 0.51 | 0.119 | 0.27 | 5.00 | 0.82 | 0.857 | 0.00 |

| post test | 5.59 | 0.46 | 5.00 | 0.86 | |||||

| Social_Resp | pre-test | 5.44 | 0.50 | 0.001 ** | 0.20 | 5.04 | 0.69 | 0.087 | 0.01 |

| post test | 5.54 | 0.49 | 5.05 | 0.74 | |||||

| SDI | pre-test | 8.49 | 3.05 | 0.001 ** | 0.33 | 5.87 | 4.13 | 0.001 ** | 0.05 |

| post test | 9.43 | 2.58 | 6.07 | 4.16 | |||||

| BPNs | pre-test | 4.03 | 0.50 | 0.001 ** | 0.26 | 3.71 | 0.65 | 0.114 | 0.07 |

| post test | 4.16 | 0.51 | 3.76 | 0.71 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Gómez-López, M. Personal and Social Responsibility Model: Differences According to Educational Stage in Motivation, Basic Psychological Needs, Satisfaction, and Responsibility. Children 2023, 10, 864. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10050864

Manzano-Sánchez D, Gómez-López M. Personal and Social Responsibility Model: Differences According to Educational Stage in Motivation, Basic Psychological Needs, Satisfaction, and Responsibility. Children. 2023; 10(5):864. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10050864

Chicago/Turabian StyleManzano-Sánchez, David, and Manuel Gómez-López. 2023. "Personal and Social Responsibility Model: Differences According to Educational Stage in Motivation, Basic Psychological Needs, Satisfaction, and Responsibility" Children 10, no. 5: 864. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10050864