Work Gains and Strains on Father Involvement: The Mediating Role of Parenting Styles

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Work–Family Conflict and Parenting

1.2. The Interplay between Work–Family Conflict, Father Involvement, and Parenting Styles

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Materials

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

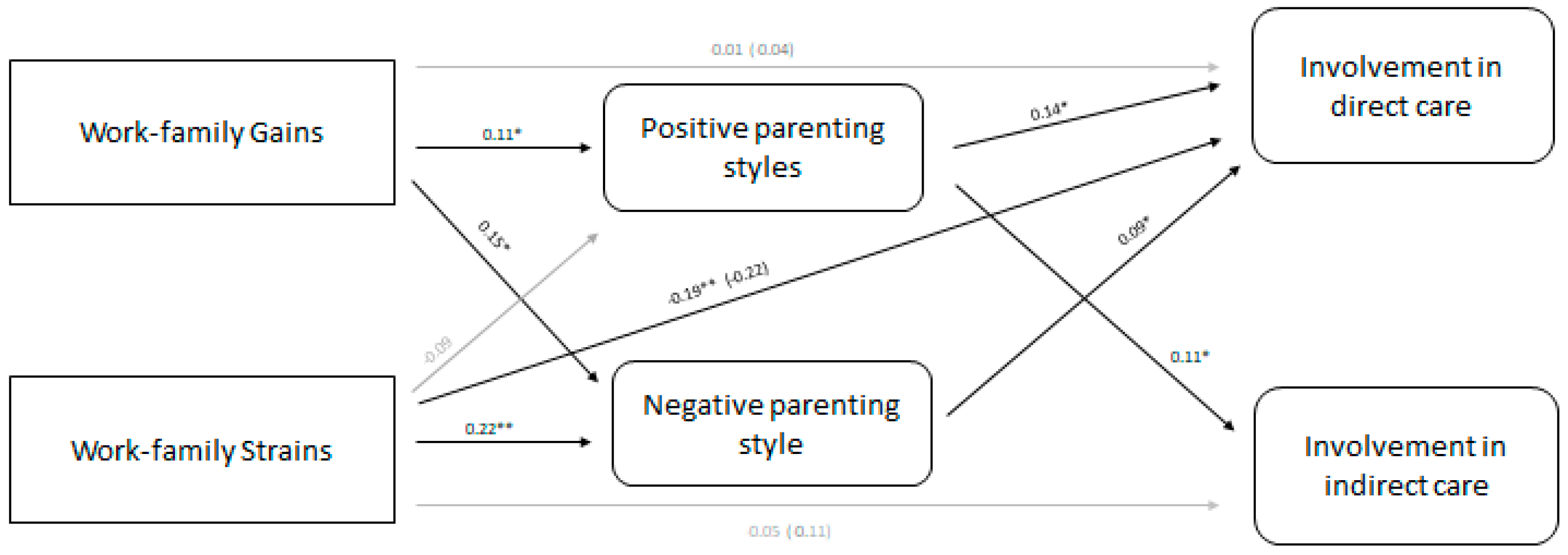

3.2. Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Labor Force Statistics by Sex and Age: Indicators [Databases]. Available online: http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=LFS_SEXAGE_I_R# (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Cabrera, N.J. Father Involvement, Father-Child Relationship, and Attachment in the Early Years. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2020, 22, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, N.J.; Volling, B.L.; Barr, R. Fathers Are Parents, Too! Widening the Lens on Parenting for Children’s Development. Child Dev. Perspect. 2018, 12, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palkovitz, R. Expanding Our Focus from Father Involvement to Father–Child Relationship Quality. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2019, 11, 576–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.A. The Work–Family Conflict: Evidence from the Recent Decade and Lines of Future Research. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2021, 42, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Family Database. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Allen, T.D.; Finkelstein, L.M. Work–Family Conflict among Members of Full-Time Dual-Earner Couples: An Examination of Family Life Stage, Gender, and Age. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bianchi, S.M.; Milkie, M.A. Work and Family Research in the First Decade of the 21st Century. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 705–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, S.; Strazdins, L.; O’Brien, L.; Sims, S. Parents’ Jobs in Australia: Work Hours Polarisation and the Consequences for Job Quality and Gender Equality. Aust. J. Labour Econ. 2011, 14, 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Parasuraman, S. The Allocation of Time to Work and Family Roles. In Gender, Work Stress, and Health; Nelson, D.L., Burke, R.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 115–128. ISBN 978-1-55798-923-9. [Google Scholar]

- Darling, N.; Steinberg, L. Parenting Style as Context: An Integrative Model. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 113, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.L.; Butler, A.B.; Grzywacz, J.G.; Linney, K.D. Do Job Demands Undermine Parenting? A Daily Analysis of Spillover and Crossover Effects. Fam. Relat. 2009, 58, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, N.L.; Barnett, R.C. Work-Family Strains and Gains among Two-Earner Couples. J. Community Psychol. 1993, 21, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giallo, R.; Treyvaud, K.; Cooklin, A.; Wade, C. Mothers’ and Fathers’ Involvement in Home Activities with Their Children: Psychosocial Factors and the Role of Parental Self-Efficacy. Early Child Dev. Care 2013, 183, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, R.C.; Hyde, J.S. Women, Men, Work, and Family: An Expansionist Theory. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frone, M.R. Work-family balance. In Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, J.M.; Matias, M.; Ferreira, T.; Lopez, F.G.; Matos, P.M. Parents’ Work-Family Experiences and Children’s Problem Behaviors: The Mediating Role of the Parent–Child Relationship. J. Fam. Psychol. 2016, 30, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cooklin, A.R.; Westrupp, E.M.; Strazdins, L.; Giallo, R.; Martin, A.; Nicholson, J.M. Fathers at Work: Work–Family Conflict, Work–Family Enrichment and Parenting in an Australian Cohort. J. Fam. Issues 2016, 37, 1611–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.X.; Volling, B.L.; Gonzalez, R. Gender Role Beliefs, Work–Family Conflict, and Father Involvement after the Birth of a Second Child. Psychol. Men Masculinity 2018, 19, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pleck, J.H. Paternal Involvement: Revised Conceptualization and Theoretical Linkages with Child Outcomes. In The Role of the Father in Child Development; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 58–93. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, S.N.; Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J.; Kotila, L.E.; Feng, X.; Kamp Dush, C.M.; Johnson, S.C. Relations Between Fathers’ and Mothers’ Infant Engagement Patterns in Dual-Earner Families and Toddler Competence. J. Fam. Issues 2014, 35, 1107–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Family Database; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2019.

- Moreira, H.; Fonseca, A.; Caiado, B.; Canavarro, M.C. Work-Family Conflict and Mindful Parenting: The Mediating Role of Parental Psychopathology Symptoms and Parenting Stress in a Sample of Portuguese Employed Parents. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cabrera, N.J.; Fitzgerald, H.E.; Bradley, R.H.; Roggman, L. The Ecology of Father-child Relationships: An Expanded Model. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2014, 6, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, M.E.; Pleck, J.H.; Charnov, E.L.; Levine, J.A. Paternal Behavior in Humans. Am. Zool. 1985, 25, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palkovitz, R.; Hull, J. Toward a Resource Theory of Fathering: Resource Theory. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2018, 10, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, N.J.; Fagan, J.; Wight, V.; Schadler, C. Influence of Mother, Father, and Child Risk on Parenting and Children’s Cognitive and Social Behaviors: Influence of Mother, Father, and Child Risk. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 1985–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ferreira, T.; Cadima, J.; Matias, M.; Vieira, J.M.; Leal, T.; Verschueren, K.; Matos, P.M. Trajectories of Parental Engagement in Early Childhood among Dual-Earner Families: Effects on Child Self-Control. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meteyer, K.; Perry-Jenkins, M. Father Involvement among Working-Class, Dual-Earner Couples. Father. J. Theory Res. Pract. Men Fathers 2010, 8, 379–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, N.; Veríssimo, M.; Monteiro, L.; Ribeiro, O.; Santos, A.J. Domains of Father Involvement, Social Competence and Problem Behavior in Preschool Children. J. Fam. Stud. 2014, 20, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, E.; Brandão, T.; Monteiro, L.; Veríssimo, M. Father Involvement during Early Childhood: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2021, 13, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleditsch, R.F.; Pedersen, D.E. Mothers’ and Fathers’ Ratings of Parental Involvement: Views of Married Dual-Earners with Preschool-Age Children. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2017, 53, 589–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, G.D.; Jewkes, R.; Esser, M.; MacNab, Y.C.; Patrick, D.M.; Buxton, J.A.; Bettinger, J.A. Exploring Low Levels of Inter-Parental Agreement Over South African Fathers’ Parenting Practices. J. Mens. Stud. 2018, 26, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monteiro, L.; Veríssimo, M.; Vaughn, B.E.; Santos, A.J.; Torres, N.; Fernandes, M. The Organization of Children’s Secure Base Behaviour in Two-Parent Portuguese Families and Father’s Participation in Child-Related Activities. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 7, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volling, B.L.; Palkovitz, R. Fathering: New Perspectives, Paradigms, and Possibilities. Psychol. Men Masc. 2021, 22, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Westman, M.; Hetty Van Emmerik, I.J. Advancements in Crossover Theory. J. Manag. Psychol. 2009, 24, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; Schwind, K.M.; Wagner, D.T.; Johnson, M.D.; DeRue, D.S.; Ilgen, D.R. When Can Employees Have a Family Life? The Effects of Daily Workload and Affect on Work-Family Conflict and Social Behaviors at Home. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1368–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, M.E.; Olson, R.E.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Story, M.; Bearinger, L.H. Correlations Between Family Meals and Psychosocial Well-Being Among Adolescents. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004, 158, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cho, E.; Allen, T.D. Relationship between Work Interference with Family and Parent–Child Interactive Behavior: Can Guilt Help? J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E.Y.H. A Mixed-Methods Study of Paternal Involvement in Hong Kong. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2016, 42, 1023–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meil, G. European Men’s Use of Parental Leave and Their Involvement in Child Care and Housework. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2013, 44, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Fatherhood and Health Outcomes in Europe: A Summary Report; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.L.; McBride, B.A.; Bost, K.K.; Shin, N. Parental Involvement, Child Temperament, and Parents’ Work Hours: Differential Relations for Mothers and Fathers. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 32, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Veríssimo, M.; Pimenta, M.; Borges, P.; Torres, N.; Martins, C. Percepções parentais acerca dos conflitos e benefícios associados com a gestão da família e do trabalho. Diáphora 2013, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Powell, G.N. When Work and Family Are Allies: A Theory of Work-Family Enrichment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.T.; Welch, G.W.; Sarver, C.M. The Relationship between Disadvantaged Fathers’ Employment Stability, Workplace Flexibility, and Involvement with Their Infant Children. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2013, 39, 380–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii-Kuntz, M. Work Environment and Japanese Fathers’ Involvement in Child Care. J. Fam. Issues 2013, 34, 250–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izci, B.; Jones, I. An Exploratory Study of Turkish Fathers’ Involvement in the Lives of Their Preschool Aged Children. Early Years 2021, 41, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kato-Wallace, J.; Barker, G.; Eads, M.; Levtov, R. Global Pathways to Men’s Caregiving: Mixed Methods Findings from the International Men and Gender Equality Survey and the Men Who Care Study. Glob. Public Health 2014, 9, 706–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D. Current Patterns of Parental Authority. Dev. Psychol. 1971, 4, 1–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.L.; Fabes, R.A. The Stability and Consequences of Young Children’s Same-Sex Peer Interactions. Dev. Psychol. 2001, 37, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paquette, D.; Bolté, C.; Turcotte, G.; Dubeau, D.; Bouchard, C. A New Typology of Fathering: Defining and Associated Variables. Infant Child Dev. 2000, 9, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Monteiro, L.; Torres, N.; Tereno, S. Implication paternelle chez des enfants d’âge préscolaire. Contributions des styles parentaux et de l’affectivité négative de l’enfant. Devenir 2021, 33, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, C.P.; Cowan, P.A. Interventions to Ease the Transition to Parenthood: Why They Are Needed and What They Can Do. Fam. Relat. 1995, 44, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, L.; Fernandes, M.; Torres, N.; Santos, C. Father’s Involvement and Parenting Styles in Portuguese Families. The Role of Education and Working Hours. Análise Psicológica 2018, 35, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, B.M.; Spinrad, T.L.; Eisenberg, N.; Greving, K.A. Parental Childrearing Attitudes as Correlates of Father Involvement During Infancy. J. Marriage Fam. 2007, 69, 962–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Braza, P.; Carreras, R.; Muñoz, J.M.; Braza, F.; Azurmendi, A.; Pascual-Sagastizábal, E.; Cardas, J.; Sánchez-Martín, J.R. Negative Maternal and Paternal Parenting Styles as Predictors of Children’s Behavioral Problems: Moderating Effects of the Child’s Sex. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin Williams, L.; Degnan, K.A.; Perez-Edgar, K.E.; Henderson, H.A.; Rubin, K.H.; Pine, D.S.; Steinberg, L.; Fox, N.A. Impact of Behavioral Inhibition and Parenting Style on Internalizing and Externalizing Problems from Early Childhood through Adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2009, 37, 1063–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Costigan, C.L.; Cox, M.J.; Cauce, A.M. Work-Parenting Linkages among Dual-Earner Couples at the Transition to Parenthood. J. Fam. Psychol. 2003, 17, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mase, J.A.; Tyokyaa, T.L. Influence of Work-Family-Conflict and Gender on Parenting Styles among Working Parents in Makurdi Metropolis. Eur. Sci. J. ESJ 2016, 12, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, S.M.; Robinson, J.P.; Milkie, M.A. Changing Rhythms of American Family Life, 1st ed.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-87154-093-5. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, C.; Martins, E.; Mateus, V.; Osório, A.; Fonseca, M. Compining work and family: Preliminar evidence. In Presentation at XIII Conferência Internacional Avaliação Psicológica: Formas e Contextos; Universidade do Minho: Braga, Portugal, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, L.; Veríssimo, M.; Pessoa e Costa, I. Parental Involvement Questionnaire: Child Care and Sociaization Related Tasks; ISPA—Instituto Universitário: Lisboa, Portugal, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pedro, M.F.; Ribeiro, M.T. Adaptação portuguesa do questionário de coparentalidade: Análise fatorial confirmatória e estudos de validade e fiabilidade. Psicol. Reflex. Crít. 2015, 28, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Computer-Assisted Research Design and Analysis; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-205-32178-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M.R. Evaluating Model Fit: A Synthesis of the Structural Equation Modelling Literature; Regent’s College: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Williams, J. Confidence Limits for the Indirect Effect: Distribution of the Product and Resampling Methods. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2004, 39, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skinner, N.; Ichii, R. Exploring a Family, Work, and Community Model of Work–Family Gains and Strains. Community Work Fam. 2015, 18, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Buehler, C. Adolescents’ Responses to Marital Conflict: The Role of Cooperative Marital Conflict. J. Fam. Psychol. 2017, 31, 910–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, H.; Cooklin, A.R.; Leach, L.S.; Westrupp, E.M.; Nicholson, J.M.; Strazdins, L. Parents’ Transitions into and out of Work-Family Conflict and Children’s Mental Health: Longitudinal Influence via Family Functioning. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 194, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywacz, G.; Marks, N.F. Reconceptualizing the Work-Family Interface: An Ecological Perspective on the Correlates of Positive and Negative Spillover between Work and Family. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenning, K.; Mabbe, E.; Soenens, B. Work–Family Conflict and Toddler Parenting: A Dynamic Approach to the Role of Parents’ Daily Work–Family Experiences in Their Day-to-Day Parenting Practices through Feelings of Parental Emotional Exhaustion. Community Work Fam. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, S.B.; Gatrell, C.J.; Cooper, C.L.; Sparrow, P. Well-balanced Families?: A Gendered Analysis of Work-life Balance Policies and Work Family Practices. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2010, 25, 534–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, M.R. Family Man in the Other America: New Opportunities, Motivations, and Supports for Paternal Caregiving. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2009, 624, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| M (SD); Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. WFS | 1.81 (0.50); 1–4 | - | - | |||||||||

| 2. WFG | 2.68 (0.56); 1–4 | −0.05 | - | |||||||||

| 3. Direct care | 2.44 (0.40); 1–3 | −0.18 ** | 0.07 | - | ||||||||

| 4. Indirect care | 2.81 (0.38); 1–4 | −0.05 | 0.09 | 0.55 ** | - | |||||||

| 5. Positive style | 3.69 (0.53); 1–5 | −0.10 * | 0.11 * | 0.13 ** | 0.09 | - | ||||||

| 6. Negative style | 2.06 (0.28); 1–3 | 0.22 ** | 0.14 * | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.27 ** | - | |||||

| 7. Father’s age (years) | 36.34; (6.15); 21–62 | −0.09 | 0.09 | −0.10 * | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.03 | - | ||||

| 8. Father’s education (years) | 10.91 (4.16); 4–19 | 0.06 | 0.13 * | 0.02 | 0.16 ** | 0.12 * | 0.03 | 0.10 * | - | |||

| 9. Working hours | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | - | |||

| 10. Child’s sex (0 = girls; 1 = boys) | - | 0.002 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.14 * | 0.07 | −0.08 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.04 | - | |

| 11. Child’s age (months) | 53.53 (12.06); 20.66–72.90 | −0.002 | 0.02 | 0.12 * | 0.08 | 0.03 | −0.11 * | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.10 * | −0.04 | - |

| Estimate | p-Value | BC 95% CI Lower/Upper | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global indirect effects | Standardized | ||

| WFG → Direct care | 0.029 | 0.007 * | 0.010/0.057 |

| WFG → Indirect care | 0.021 | 0.050 * | 0.002/0.047 |

| WFS → Direct care | 0.020 | 0.669 | −0.016/0.031 |

| WFS → Indirect care | 0.012 | 0.439 | −0.016/0.028 |

| Specific indirect effects | Unstandardized | ||

| WFG → PPS → Direct care | 0.011 | 0.028 * | 0.002/0.027 |

| WFG → PPS → Indirect care | 0.007 | 0.050 * | 0.001/0.022 |

| WFG → NPS → Direct care | 0.010 | 0.031 * | 0.002/0.023 |

| WFG → NPS → Indirect care | 0.007 | 0.107 | 0.000/0.018 |

| WFS → PPS → Direct care | −0.010 | 0.071 | −0.030/-0.001 |

| WFS → PPS → Indirect care | −0.007 | 0.088 | −0.027/0.000 |

| WFS → NPS → Direct care | 0.017 | 0.037 * | 0.003/0.035 |

| WFS → NPS → Indirect care | 0.011 | 0.140 | −0.001/0.030 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diniz, E.; Monteiro, L.; Veríssimo, M. Work Gains and Strains on Father Involvement: The Mediating Role of Parenting Styles. Children 2023, 10, 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081357

Diniz E, Monteiro L, Veríssimo M. Work Gains and Strains on Father Involvement: The Mediating Role of Parenting Styles. Children. 2023; 10(8):1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081357

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiniz, Eva, Lígia Monteiro, and Manuela Veríssimo. 2023. "Work Gains and Strains on Father Involvement: The Mediating Role of Parenting Styles" Children 10, no. 8: 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081357