The Childbirth Experiences of Pregnant Women Living with HIV Virus: Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

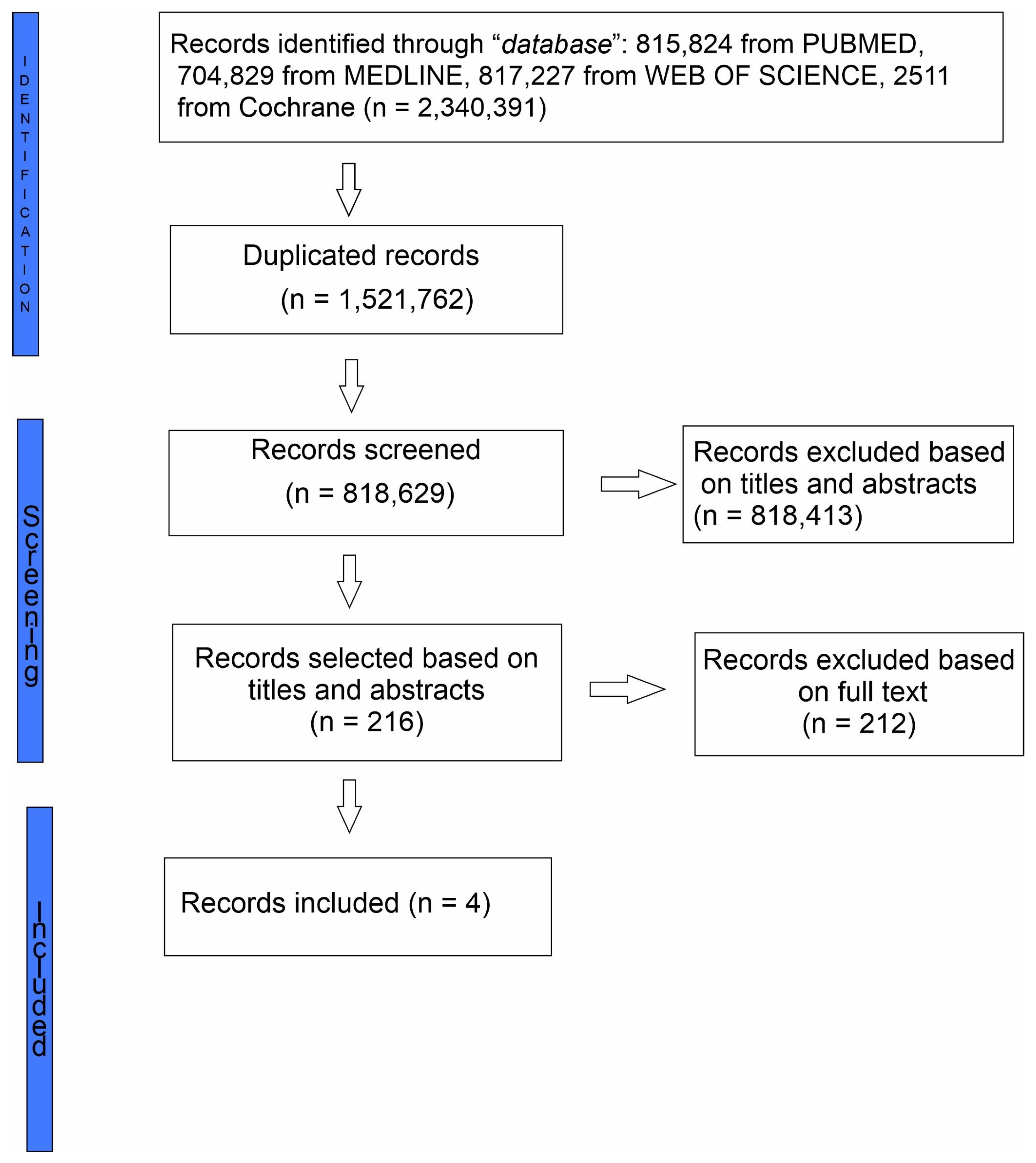

2. Methodology

- Stage 1: identify the research.

- Stage 2: identify relevant studies.

- Stage 3: study selection

- Stage 4: charting the data

- Stage 5: collating, summarising and reporting

3. Results

3.1. Analysing the Quality of Childbirth Experiences

3.2. Vulnerability

3.3. Autonomy of PWLWHIV

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Areas for Further Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nunes, A.R.; Lee, K.; O’riordan, T. The Importance of an Integrating Framework for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: The Example of Health and Well-Being. 2023. Available online: http://gh.bmj.com/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Marchant, T.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Black, R.; Grove, J.; Kyobutungi, C.; Peterson, S. Advancing measurement and monitoring of reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health and nutrition: Global and country perspectives Handling editor Seye Abimbola. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, 111–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reproductive Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health (RMNCAH)|UNICEF Uganda [Internet]. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/uganda/what-we-do/rmncah (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Greene, S.; Ion, A.; Kwaramba, G.; Smith, S.; Loutfy, M.R. “Why are you pregnant? What were you thinking?”: How women navigate experiences of HIV-related stigma in medical settings during pregnancy and birth. Soc. Work Health Care 2016, 55, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmond, A.M.; Mcnamara, J.F. The road to eliminate mother-to-child HIV transmission, O caminho para eliminação da transmissão vertical do HIV. J. Pediatr. (Versão Port.) 2015, 91, 509–511. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-arv (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Geldsetzer, P.; Yapa, H.M.N.; Vaikath, M.; Ogbuoji, O.; Fox, M.P.; Essajee, S.M.; Negussie, E.K.; Bärnighausen, T. A systematic review of interventions to improve postpartum retention of women in PMTCT and ART care. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2016, 19, 20679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNAIDS Brasil—Website institucional do Programa Conjunto das Nações Unidas sobre HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) no Brasil. [Internet]. Available online: https://unaids.org.br/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- de Nazaré Mota Trindade, L.; Nogueira, L.M.V.; Rodrigues, I.L.A.; Ferreira, A.M.R.; Corrêa, G.M.; Andrade, N.C.O. HIV infection in pregnant women and its challenges for the prenatal care. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2021, 74 (Suppl. S4), e20190784. [Google Scholar]

- Redshaw, M. Women as consumers of maternity care: Measuring “satisfaction” or “dissatisfaction”? Birth 2008, 35, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, M.G.; Ford, J.B.; Morris, J.M.; Roberts, C.L. Women’s expectations and experiences of maternity care in NSW—What women highlight as most important. Women Birth 2014, 27, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaro Blazquez, R.; Corchon, S.; Ferrer Ferrandiz, E. Validity of instruments for measuring the satisfaction of a woman and her partner with care received during labour and childbirth: Systematic review. Midwifery 2017, 55, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Lu, H. Childbirth expectations and correlates at the final stage of pregnancy in Chinese expectant parents. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2014, 1, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Batbaatar, E.; Dorjdagva, J.; Luvsannyam, A.; Amenta, P. Conceptualisation of patient satisfaction: A systematic narrative literature review. Perspect. Public Health 2015, 135, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukamurigo, J.; Berg, M.; Nyirazinyoye, L.; Bogren, M.; Dencker, A. Women’s childbirth experience emphasizing own capacity and safety: A cross-sectional Rwandan study. Women Birth 2021, 34, e146–e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, K.S. Childbirth Education for the HIV-Positive Woman. J. Perinat. Educ. 2003, 12, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cichowitz, C.; Watt, M.H.; Mmbaga, B.T. Childbirth experiences of women living with HIV: A neglected event in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission care continuum. AIDS 2018, 32, 1537–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turan, J.M.; Hatcher, A.H.; Medema-Wijnveen, J.; Onono, M.; Miller, S.; Bukusi, E.A.; Turan, B.; Cohen, C.R. The Role of HIV-Related Stigma in Utilization of Skilled Childbirth Services in Rural Kenya: A Prospective Mixed-Methods Study. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medema-Wijnveen, J.S.; Onono, M.; Bukusi, E.A.; Miller, S.; Cohen, C.R.; Turan, J.M. How Perceptions of HIV-Related Stigma Affect Decision-Making Regarding Childbirth in Rural Kenya. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susan, A.; Harris, R.; Sawyer, A.; Parfitt, Y.; Ford, E. Posttraumatic stress disorder after childbirth: Analysis of symptom presentation and sampling. J. Affect Disord. 2009, 119, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildiz, P.D.; Ayers, S.; Phillips, L. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy and after birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect Disord. 2017, 208, 634–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Pollock, D.; Khalil, H.; Alexander, L.; Mclnerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Peters, M.; Tricco, A.C. What are scoping reviews? Providing a formal definition of scoping reviews as a type of evidence synthesis. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 950–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; Mcinerney, P.; Soares, C.; Khalil, H.; Parker, D. Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews; 2015; pp. 1–24. Available online: https://reben.com.br/revista/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Scoping.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, W-65–W-94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, B.; Salanti, G.; Caldwell, D.M.; Chaimani, A.; Schmid, C.H.; Cameron, C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Straus, S.; Thorlund, K.; Jansen, J.P.; et al. The PRISMA Extension Statement for Reporting of Systematic Reviews Incorporating Network Meta-analyses of Health Care Interventions: Checklist and Explanations. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Azevedo, A.P.; Hofer, C.B. Scoping Review of Childbirth Experience in Pregnant Women Living with HIV Virus. 2023. Available online: https://osf.io/wx52k/ (accessed on 4 June 2023).

- The Scoping Review and Summary of the Evidence—JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis—JBI Global Wiki [Internet]. Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/355598371/1.+JBI+Systematic+Reviews (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Peters, M.D.; Mclnerney, P.A.; Khalil, H.; Godfrey, C.M.; Alexander, L.A.; Munn, Z. Methodological quality, guidance, and tools in scoping reviews: A scoping review protocol. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 1098–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H.; Holly, C.; Feyissa, G.; Godfrey, C.; Evans, C.; Sawchuck, D.; Sudhakar, M.; Asahngwa, C.; Stannard, D.; et al. Rapid reviews and the methodological rigor of evidence synthesis: A JBI position statement. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 944–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotto, P.C.B.; Lopez, L.C.; Piccinini, C.A.; Gonçalves, T.R. Entre a mulher e a salvação do bebê: Experiências de parto de mulheres com HIV. Interfac—Comun. Saúde Educ. 2019, 23, e180556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sando, D.; Kendall, T.; Lyatuu, G.; Ratcliffe, H.; Mcdonald, K.; Mwanyika-Sando, M.; Emil, F.; Chalamilla, C.; Langer, A. Disrespect and Abuse during Childbirth in Tanzania: Are Women Living with HIV More Vulnerable? J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 2014, 67, S228–S234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin-Hughes, M.; Proulx-Boucher, K.; Rodrigue, C.; Otis, J.; Kaida, A.; Boucoiran, I.; Greene, S.; Kennedy, L.; Webster, K.; Conway, T.; et al. Previous experiences of pregnancy and early motherhood among women living with HIV: A latent class analysis. AIDS Care 2019, 31, 1427–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psaros, C.; Remmert, J.E.; Bangsberg, D.R.; Safren, S.A.; Smit, J.A. Adherence to HIV Care after Pregnancy among Women in Sub-Saharan Africa: Falling Off the Cliff of the Treatment Cascade Compliance with Ethics Guidelines Conflict of Interest HHS Public Access. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chabbert, M.; Panagiotou, D.; Wendland, J. Predictive factors of women’s subjective perception of childbirth experience: A systematic review of the literature. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2021, 39, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, R.M.; Phiri, K.; Parent, J.; Grotts, J.; Elashoff, D.; Kawale, P.; Yeatman, S.; Currier, J.S.; Schooley, A. Factors associated with retention in Option B+ in Malawi: A case control study. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzyamba, C.; Groot, W.; Tomini, S.M.; Pavlova, M. The usefulness of traditional birth attendants to women living with HIV in resource-poor settings: The case of Mfuwe, Zambia. Trop. Med. Health 2017, 45, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, A.; Ayers, S.; Abbott, J.; Gyte, G.; Rabe, H.; Duley, L. Measures of satisfaction with care during labour and birth: A comparative review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, P.; Mackey, M.C.; Tavakoli, A.S. Factors related to childbirth satisfaction. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 46, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero, P.; Delgado-García, B.E.; Orts-Cortes, I.; Moncho, J.; Pereyra-Zamora, P.; Nolasco, A. Validation of the Spanish version of mackey childbirth satisfaction rating scale. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sociedad Española de Salud Pública y Administración Sanitaria; Barona-Vilar, C.; Carreguí-Vilar, S.; Ibáñez-Gil, N.; Margaix-Fontestad, L.; Escribà-Agüir, V. Gaceta Sanitaria; Sociedad Española de Salud Pública y Administración Sanitaria (SESPAS): Barceloa, Spain, 2012; Volume 26, pp. 236–242. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0213-91112012000300009&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Moudi, Z.; Tavousi, M. Evaluation of Mackey Childbirth Satisfaction Rating Scale in Iran: What Are the Psychometric Properties? Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2016, 5, e29952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabakian-Khasholian, T.; Bashour, H.; El-Nemer, A.; Kharouf, M.; Sheikha, S.; El Lakany, N.; Barakat, R.; Elsheikh, O.; Nameh, N.; Chahine, R.; et al. Women’s satisfaction and perception of control in childbirth in three Arab Countries. Reprod. Health Matters 2017, 25, S16–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F.; Nakamura, M.U.; Nomura, R.M.Y. Women’s satisfaction with childbirth in a public hospital in Brazil. Birth 2021, 48, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F.; Júnior, N.C.; Nakamura, M.U.; Nomura, R.M.Y. Content and Face Validity of the Mackey Childbirth Satisfaction Rating Scale Questionnaire Cross-culturally Adapted to Brazilian Portuguese. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obs./RBGO Gynecol. Obstet. 2019, 41, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, F.; Júnior, N.C.; Nakamura, M.U.; Nomura, R.M.Y. Psychometric properties of the Mackey Childbirth Satisfaction Rating Scale cross-culturally adapted to Brazilian Portuguese. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021, 34, 2173–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomas, J.; Dore, S.; Enkin, M.; Mitchell, A. The Labor and Delivery Satisfaction Index: The Development and Evaluation of a Soft Outcome Measure. Birth 1987, 14, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.F.P.; Somerset, E. Development of a multidimensional labour satisfaction questionnaire: Dimensions, validity, and internal reliability. Qual. Health Care 2001, 10, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, N.R.; Wallston, K.A.; Hamilton, N.A. Perceived control and maternal satisfaction with childbirth: A measure development study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 33, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannarini, S.; Boffo, M.; Bertucci, V.; Andrisani, A.; Ambrosini, G.; Professor, A. A Rasch-based dimension of delivery experience: Spontaneous vs. medically assisted conception. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 2404–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbins, J.; Thomson, A.M. Women’s expectations and experiences of childbirth. Midwifery 2001, 17, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, B.P.; Nobre, C.M.G.; Costa, A.R.; Nornberg, P.K.O.; Medeiros, S.P.; Gomes, G.C. Human immunodeficiency syndrome in children: Repercussions for the family. Rev. Enferm. UFPE Online 2019, 13, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.B.; da Graça Corso da Motta, M.; Bellenzani, R. Experience of pregnancy and maternity by adolescents/young people born infected with HIV. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73 (Suppl. 4), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandes, C.P.; Da Rocha, R.K.; Hausmann, A.; Appelt, J.B.; de Mattos Marques, C. Análise qualitativa dos sentimentos e conhecimentos acerca da gestação e do HIV em gestantes soropositivas e soronegativas. J. Health Biol. Sci. 2018, 7, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, K.; Lindberg, I.; Öhrling, K. Midwives’ experience of encountering women with posttraumatic stress symptoms after childbirth. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2010, 1, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clouse, K.; Motlhatlhedi, M.; Bonnet, K.; Schlundt, D.; Aronoff, D.M.; Chakkalakal, R.; Norris, S.A. “I just wish that everything is in one place”: Facilitators and barriers to continuity of care among HIV-positive, postpartum women with a non-communicable disease in South Africa HHS Public Access. AIDS Care 2018, 30 (Suppl. 2), 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taheri, M.; Takian, A.; Taghizadeh, Z.; Jafari, N.; Sarafraz, N. Creating a positive perception of childbirth experience: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prenatal and intrapartum interventions. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohren, M.A.; Berger, B.O.; Munthe-Kaas, H.; Tunçalp, Ö. Perceptions and experiences of labour companionship: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2019, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Recommendations: Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550215 (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Dickens, B. I095 the FIGO Principles and Practice of Bioethics Curriculum. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2012, 119, S183–S184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balde, M.D.; Nasiri, K.; Mehrtash, H.; Soumah, A.-M.; A Bohren, M.; Diallo, B.A.; Irinyenikan, T.A.; Maung, T.M.; Thwin, S.S.; Aderoba, A.K.; et al. Labour companionship and women’s experiences of mistreatment during childbirth: Results from a multi-country community-based survey. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 5 (Suppl. 2), e003564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munkhondya, B.M.J.; Munkhondya, T.E.; Chirwa, E.; Wang, H. Efficacy of companion-integrated childbirth preparation for childbirth fear, self-efficacy, and maternal support in primigravid women in Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreitchmann, R.; Harris, D.R.; Kakehasi, F.; Haberer, J.E.; Cahn, P.; Losso, M.; Teles, E.; Pilotto, J.H.; Hofer, C.B.; Jennifer, S. Antiretroviral Adherence During Pregnancy and Postpartum in Latin America. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2012, 26, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, S.; Tan, Y.; Lu, B.; Cheng, Y.; Nong, Y. Survey and analysis for impact factors of psychological distress in HIV-infected pregnant women who continue pregnancy. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2018, 32, 3160–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond-Smith, N.; Sudhinaraset, M.; Melo, J.; Murthy, N. The relationship between women’s experiences of mistreatment at facilities during childbirth, types of support received and person providing the support in Lucknow, India. Midwifery 2016, 40, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annborn, A.; Finnbogadóttir, H.R. Obstetric violence a qualitative interview study. Midwifery 2022, 105, 103212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Galiano, J.M.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J.; Rubio-Álvarez, A.; Ortiz-Esquinas, I.; Ballesta-Castillejos, A.; Hernández-Martínez, A. Obstetric Violence from a Midwife Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sousa Carvalho, A.; Gomes, A.; Pedroga, R.; Ribeiro, C.M.; De Assis, L.; Helvécio Kalil, J.; De Oliveira Nascimento E Silva, S.A. Violência obstétrica: A ótica sobre os princípios bioéticos e direitos das mulheres [obstetric violence: The optics on the bioethic principles and rights of women]. Braz. J. Surg. Clin. Res. BJSCR 2019, 26, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Jardim, D.M.B.; Modena, C.M. Obstetric violence in the daily routine of care and its characteristics. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2018, 26, e3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coubcil of Europe. Obstetrical and Gynaecological Violence. Available online: https://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/Xref-XML2HTML-en.asp?fileid=28236&lang=en (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Jewkes, R.; Penn-Kekana, L. Mistreatment of Women in Childbirth: Time for Action on This Important Dimension of Violence against Women. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viirman, F.; Hesselman, S.; Wikström, A.-K.; Svanberg, A.S.; Skalkidou, A.; Poromaa, I.S.; Wikman, A. Negative childbirth experience—What matters most? A register-based study of risk factors in three time periods during pregnancy. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2022, 34, 100779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chabbert, M.; Rozenberg, P.; Wendland, J. Predictors of Negative Childbirth Experiences Among French Women. JOGNN J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2021, 50, 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, B.H.; Johnston, J.M.; Vackova, D.; Hassen, S.M.; Yi, H. The role of male partner in utilization of maternal health care services in Ethiopia: A community-based couple study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emelonye, A.U.; Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K.; Pitkäaho, T.; Aregbesola, A. Midwives perceptions of partner presence in childbirth pain alleviation in Nigeria hospitals. Midwifery 2017, 48, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Declaração Universal sobre Bioética e Direitos Humanos. 2006. Available online: www.unesco.org/shs/ethics (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- da Silva, A.F.P.M.; de Almeida, B.G.R.F.; Ribeiro, E.A.; Teixeira, L.C.; de Oliveira da Silva, P.C.P.; da Silva Ribeiro, A. Obstetric violence related to the loss of autonomy of the womanin the children’s room. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e22210514814. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, J.O.; Adrián, C.; Fernández, C.; Mella, M.; Villagrán, M.; Diaz, M.; Quiroz, J. Childbirth experiences of immigrant women in Chile: Trading human rights and autonomy for dignity and good care. Midwifery 2021, 101, 103047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, B. Is the narrow concept of individual autonomy compatible with or in conflict with Evidence-based Medicine in obstetric practice?: A philosophical critique on the misapplication of the value concept “autonomy”. Woman—Psychosom. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2014, 1, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onchonga, D.; Várnagy, Á.; Keraka, M.; Wainaina, P. Midwife-led integrated pre-birth training and its impact on the fear of childbirth. A qualitative interview study. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2020, 25, 100512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroll, C.; Murphy, J.; Poston, L.; You, W.; Premkumar, A. Cultivating the ideal obstetrical patient: How physicians-in-training describe pain associated with childbirth. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 312, 115365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbutė, A.; Paulionytė, M.; Jonauskaitė, D.; Machtejevienė, E.; Nadišauskienė, R.J.; Dambrauskas, Ž.; Dobožinskas, P.; Kliučinskas, M. Perceived changes in knowledge and confidence of doctors and midwives after the completion of the Standardized Trainings in Obstetrical Emergencies. Medicina 2017, 53, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| P-population | Pregnant women living with HIV |

| C-concept | Satisfaction or experience of pregnant women at childbirth |

| C-context | Childbirth |

| No | Title/Author/Year | Country | Aim | Type of Research | Data Collection | Sample Size | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Between the Woman and saving the baby: HIV positive women’s experience of giving birth (Bellotto et al., 2019 [35]) | Brazil | To analyse the experience of childbirth of women living with HIV. | Qualitative approach and psychological analysis | Many in-depth interviews for each woman living with HIV | 6 women living with HIV | Women living with HIV expressed greater concern about ensuring the health of their newborn, preventing transmission of HIV, rather than focusing on their own childbirth experience. Only two women who had previously undergone childbirth were concerned about their own experience and autonomy during the process. |

| 2 | “Why are you pregnant? What were you thinking?: How women navigate experiences of HIV-related stigma in medical settings during pregnancy and birth. (Greene at al., 2016 [4]) | Canada | To understand and respond to women’s unique experiences and psychological challenges during pregnancy and birth. | Qualitative study | Narrative interviews | 66 pregnant women living with HIV | The narratives of women living with HIV reveal the environments where stigmatising practices arise as these women seek perinatal care and support. Additionally, these narratives shed light on the correlation between HIV-related stigma, disclosure, and their profound impact on women’s pregnancy and childbirth experiences. |

| 3 | Disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Tanzania: Are women living with HIV more vulnerable? (Sando et al., 2014 [36]) | Tanzania | To explore instances of disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Tanzania, the study aimed to compare experiences between pregnant women living with HIV and those not living with HIV. | Prospective qualitative study (interview) | Mixed-method design post-partum interviews, direct observation (208), in-depth interviews (18), health care provider self-report (50) | HIV + 147 (7%) HIV − 1807 (91%) 2% unknown HIV status | Among women living with HIV and those who are HIV negative, 12.2% and 15.0% respectively reported experiencing disrespect and abuse during childbirth (p = 0.37). No significant differences were found between the experiences of women living with HIV and HIV-negative women in various forms of disrespect and abuse, except for women living with HIV, who exhibited higher odds of reporting non-consented care (p = 0.03). |

| 4 | Previous experiences of pregnancy and early motherhood among women living with HIV: a latent class analysis. (Fortin-Hughes et al., 2019 [37]) | Canada | To analyse how previous childbirth experiences influence the current childbirth experience. | Multicentric study in Canada Cohort Study | Survey/questionary | 905 women living with HIV | The analysis revealed that the majority (70.8%) of pregnancies occurred before the HIV diagnosis. A four-class maternity experience model was identified, comprising the following categories: “overall positive experience” (40%), “positive experience with postpartum challenges” (23%), “overall mixed experience” (14%), and “overall negative experience” (23%). Furthermore, no correlations were found between the timing of HIV diagnosis (before, during, or after pregnancy) and the identified patterns of childbirth experience. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Azevedo, A.P.; de Rezende Filho, J.F.; Hofer, C.B.; Rego, F. The Childbirth Experiences of Pregnant Women Living with HIV Virus: Scoping Review. Children 2024, 11, 743. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060743

de Azevedo AP, de Rezende Filho JF, Hofer CB, Rego F. The Childbirth Experiences of Pregnant Women Living with HIV Virus: Scoping Review. Children. 2024; 11(6):743. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060743

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Azevedo, Andréa Paula, Jorge Fonte de Rezende Filho, Cristina Barroso Hofer, and Francisca Rego. 2024. "The Childbirth Experiences of Pregnant Women Living with HIV Virus: Scoping Review" Children 11, no. 6: 743. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060743

APA Stylede Azevedo, A. P., de Rezende Filho, J. F., Hofer, C. B., & Rego, F. (2024). The Childbirth Experiences of Pregnant Women Living with HIV Virus: Scoping Review. Children, 11(6), 743. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060743