Care Pathways in Rehabilitation for Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: Distinctiveness of the Adaptation to the Italian Context

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- What are the fundamentals of a comprehensive management of children and adolescents with CP?

- Which rehabilitation approaches should be considered to improve gross motor or manual performance in children and adolescents with CP?

3. Results

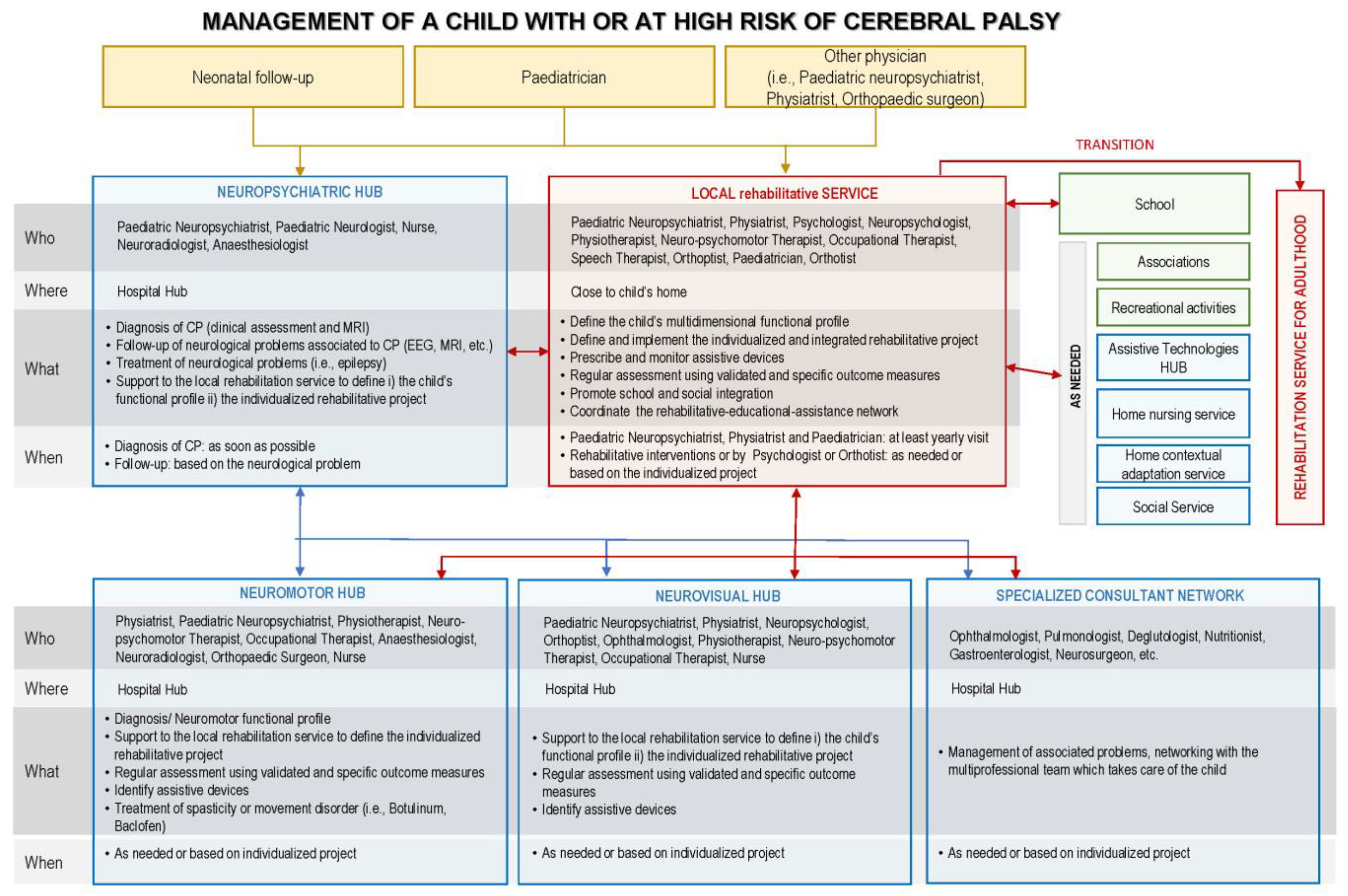

3.1. Four Strong Positive Recommendations Were Developed Regarding Comprehensive Management (Query 1):

- Offer a management program oriented to specific goals that is individually tailored and that takes into consideration the following:

- The needs and preferences of the young patient and his/her caregivers;

- The multidimensional profile of functioning of the child (physical, mental, emotional, communicative, and relational);

- Activities, as interventions and goals, that must be adequate to the age and the developmental stage;

- Functional ability scales (Gross Motor Function Classification System, GMFCS; Manual Ability Classification System, MACS; Communication Function Classification System, CFCS; Visual Function Classification System, VFCS; Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System, EDACS), with reference curves addressing prognosis for GMFCS and MACS;

- Evidence-based approaches;

- Any implication for the patient and the caregivers and individual barriers;

- Contextual barriers.

- Regularly assess the child or adolescent by means of validated specific outcome measures to set realistic goals and verify their achievement; consequently, adapt the program;

- Offer a transdisciplinary team approach, including all pediatric care professionals with expertise in CP management who may work in the same institution or as a network within the geographical area closest to the patient;

- Ensure transition to adult services with expertise regarding cerebral palsy.

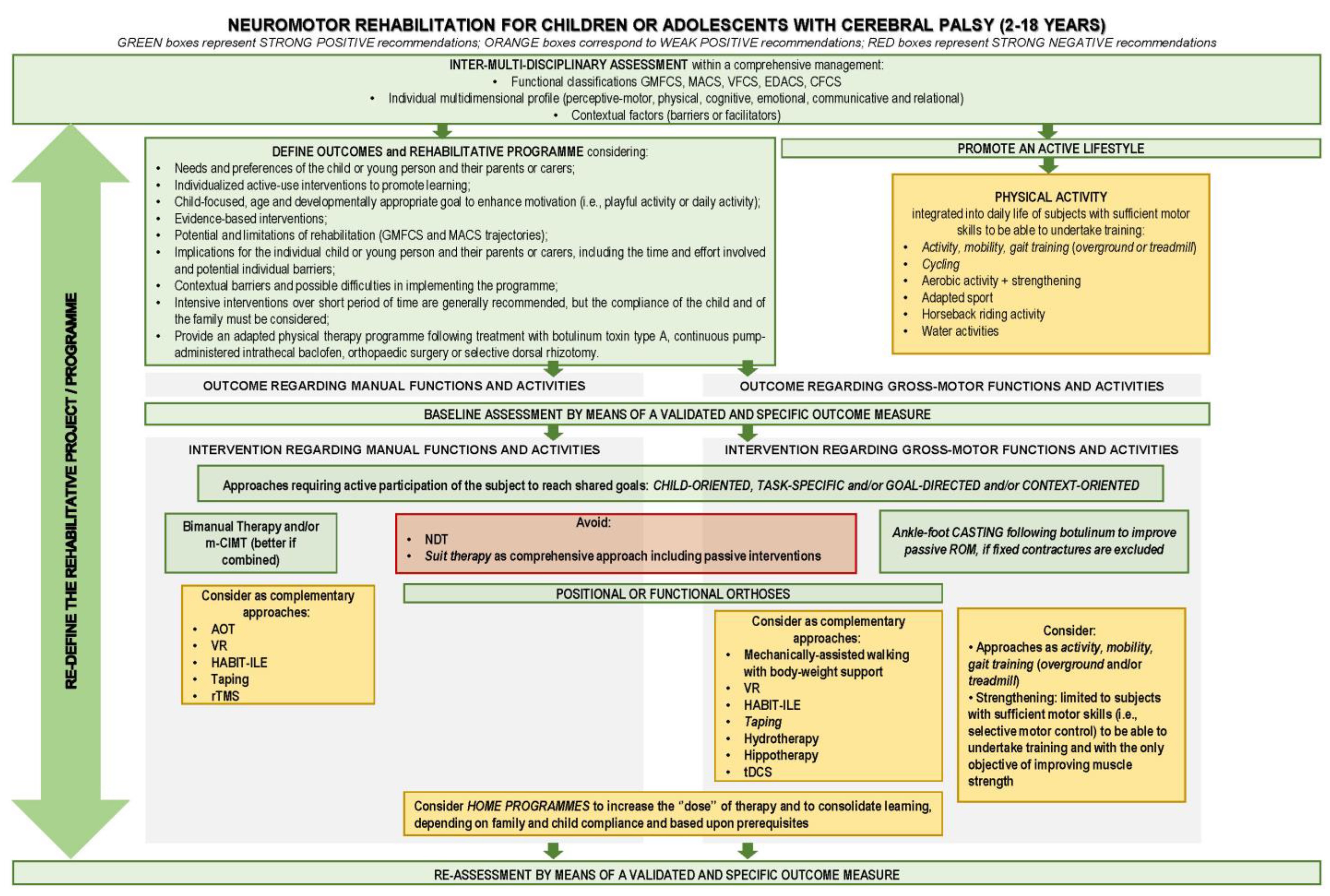

3.2. Query 2—“Motor Rehabilitation of Children and Adolescents with CP” Care Pathway

- The motor rehabilitation interventions to improve gross motor or manual skills should consider the following issues:

- -

- Individualized and active;

- -

- Child-focused, age- and developmentally appropriate goals to enhance motivation;

- -

- The child’s multidimensional profile and environmental limitations;

- -

- Implications for the patient and his/her family;

- -

- The intervention should include individually tailored adaptations of the task and/or of the context (objects and environment) to help engagement and counteract frustration;

- -

- Repetitive practice of a task or part of it should be performed based on the child’s compliance;

- -

- Intensiveness increases effectiveness, but it is subordinated to the child’s compliance.

- Consider bimanual interventions, such as performing functional tasks within enjoyable and playful activities, to improve bimanual skills in CP subjects. Bimanual interventions are intended to involve practicing a specific task or goal or parts of the task, focusing on the “activities” dimension rather than on “body and function”. Consider the need for minimum cognitive capacity as a requirement for bimanual training;

- Consider modified Constraint Induced Movement Therapy (mCIMT) combined with bimanual therapy in unilateral CP to enhance manual skills. mCIMT might be applied up to two hours a day for a period of 2–10 weeks, performing functional tasks within enjoyable and playful activities. Consider reduced compliance and possible frustration, in particular with subjects with poorer function, as a limitation to applying mCIMT;

- Consider the following factors in the selection of mCIMT or bimanual intensive interventions:

- -

- Preferences and peculiarities of the child or adolescent and his/her family features;

- -

- Expertise of the rehabilitation professionals involved;

- -

- Resources and service delivery models.

- Provide an adapted physical therapy program following treatment with botulinum toxin type A, continuous pump-administered intrathecal baclofen, orthopedic surgery, or selective dorsal rhizotomy;

- Consider task-specific, intensive, active rehabilitation to improve or recover after orthopedic surgery, as well as gross motor skills such as sitting, standing, balance, and gait. Equipment and orthoses may be used to assist in maintaining the person’s appropriate posture and movement;

- As subjects with typical development, CP subjects with sufficient motor capacity should reduce sedentary behavior and perform light-intensity activities throughout the day as fitness training (i.e., gross motor activity training, cycling, overground or treadmill walking, modified sports). Nonetheless, the benefits, in terms of gross motor function and aerobic fitness, are short-lived and recede in case of suspension of training;

- Consider upper and lower limbs:

- -

- Positional orthoses (i.e., leg or elbow orthoses, spinal braces) to maintain corrected anatomical alignment or range of motion of the joint and/or skin integrity;

- -

- Functional orthoses (i.e., ankle–foot, wrist, and thumb orthoses) to enable or improve function.

- Consider ankle–foot casting following botulinum injection with the aim of improving dorsiflexion passive range of motion.

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bax, M.C.; Flodmark, O.; Tydeman, C. Definition and classification of cerebral palsy. From syndrome toward disease. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. Suppl. 2007, 109, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe. Surveillance of cerebral palsy in Europe: A collaboration of cerebral palsy surveys and registers. Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe (SCPE). Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2000, 42, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, E.; Fazzi, E. SIMFER-SINPIA Intersociety Commission. Recommendations for the rehabilitation of children with cerebral palsy. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 52, 691–703. [Google Scholar]

- Kolaski, K. Instructions for AACPDM care pathway development 2020 edition. 2020. Available online: https://www.aacpdm.org/UserFiles/file/InstructionsforAACPDMCarePathwayDevelopment2020Edition13Oct2020KK.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- World Health Organization. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- NICE Guidelines: Managing Cerebral Palsy in under 25s. 2021. Available online: http://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/cerebral-palsy (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- NICE Guidelines: Spasticity in under 19s: Management (2012–2016). Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg145 (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Management of Cerebral Palsy in Children: A Guide For Allied Health Professionals. 2018. Available online: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/kidsfamilies/ (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Novak, I.; Morgan, C.; Fahey, M.; Finch-Edmondson, M.; Galea, C.; Hines, A.; Langdon, K.; Mc Namara, M.; Paton, M.C.; Popat, H.; et al. State of the Evidence Traffic Lights 2019: Systematic Review of Interventions for Preventing and Treating Children with Cerebral Palsy. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2020, 20, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faccioli, S.; Pagliano, E.; Ferrari, A.; Maghini, C.; Siani, M.F.; Sgherri, G.; Cappetta, G.; Borelli, G.; Farella, G.M.; Foscan, M.; et al. Evidence-based management and motor rehabilitation of cerebral palsy children and adolescents: A systematic review. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1171224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schünemann, H.J.; Wiercioch, W.; Brozek, J.; Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta, I.; Mustafa, R.A.; Manja, V.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Neumann, I.; Falavigna, M.; Alhazzani, W.; et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks for adoption, adaptation, and de novo development of trustworthy recommendations: GRADE-ADOLOPMENT. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 81, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwers, M.C.; Spithoff, K.; Kerkvliet, K.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Burgers, J.; Cluzeau, F.; Férvers, B.; Graham, I.; Grimshaw, J.; Hanna, S.; et al. Development and Validation of a Tool to Assess the Quality of Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e205535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, A.; Kelly, S.E.; Hsieh, S.C.; Skidmore, B.; Wells, G.A. Systematic reviews of clinical practice guidelines: A methodological guide. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 108, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Henry, D.A. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Barker, T.H.; Moola, S.; Tufanaru, C.; Stern, C.; McArthur, A.; Stephenson, M.; Aromataris, E. Methodological quality of case series studies: An introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2127–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.L.; Walter, S.D.; Hanna, S.E.; Palisano, R.J.; Russell, D.J.; Raina, P.; Wood, E.; Bartlett, D.J.; Galuppi, B.E. Prognosis for gross motor function in cerebral palsy: Creation of motor development curves. JAMA 2002, 288, 1357–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klevberg, G.L.; Elvrum, A.G.; Zucknick, M.; Elkjaer, S.; Østensjø, S.; Krumlinde-Sundholm, L.; Kjeken, I.; Jahnsen, R. Development of bimanual performance in young children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2018, 60, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, A.C.; Nordstrand, L.; Backheden, M.; Holmefur, M. Longitudinal development of hand use in children with unilateral spastic cerebral palsy from 18 months to 18 years. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2022, 65, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roostaei, M.; Baharlouei, H.; Azadi, H.; Fragala-Pinkham, M.A. Effects of Aquatic Intervention on Gross Motor Skills in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2017, 37, 496–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghai, S.; Ghai, I. Virtual Reality Enhances Gait in Cerebral Palsy: A Training Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackman, M.; Lannin, N.; Galea, C.; Sakzewski, L.; Miller, L.; Novak, I. What is the threshold dose of upper limb training for children with cerebral palsy to improve function? A systematic review. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2020, 67, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamdar, K.; Molinini, R.M.; Panibatla, S.T.; Chow, J.C.; Dusing, S.C. Physical therapy interventions to improve sitting ability in children with or at-risk for cerebral palsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2021, 63, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.W.; Kang, Y.N.; Tseng, S.H. Effects of Therapeutic Exercise Intensity on Cerebral Palsy Outcomes: A Systematic Review With Meta-Regression of Randomized Clinical Trials. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.P.; Ganesh, G.S. Evidence-based approach to physical therapy in cerebral palsy. Indian. J. Orthop. 2019, 53, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmari, K.; Tedla, J.S.; Sangadala, D.R.; Mukherjee, D.; Reddy, R.S.; Bairapareddy, K.C.; Kandakurti, P.K. Effectiveness of Hand-Arm Bimanual Intensive Therapy on Hand Function among Children with Unilateral Spastic Cerebral Palsy: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. Neurol. 2020, 83, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, R.G.; Yang, C.N.; Qu, Y.L.; Koduri, M.P.; Chien, C.W. Effectiveness of hand-arm bimanual intensive training on upper extremity function in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2020, 25, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoare, B.J.; Wallen, M.A.; Thorley, M.N.; Jackman, M.L.; Carey, L.M.; Imms, C. Constraint-induced movement therapy in children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 4, CD004149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckers, L.W.M.E.; Geijen, M.M.E.; Kleijnen, J.; Rameckers, E.A.; Schnackers, M.L.; Smeets, R.J.; Janssen-Potten, Y.J. Feasibility and effectiveness of home-based therapy programs for children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhaleem, N.; Taher, S.; Mahmoud, M.; Hendawy, A.; Hamed, M.; Mortada, H.; Magdy, A.; El-Din, M.R.E.; Zoukiem, I.; Elshennawy, S. Effect of action observation therapy on motor function in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials with meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2021, 35, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamer, A.; Melese, H.; Adugna, B. Effectiveness of Action Observation Training on Upper Limb Motor Function in Children with Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pediatric Health Med. Ther. 2020, 11, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsi, C.; Santos, M.M.; Moreira, R.F.C.; Dos Santos, A.N.; de Campos, A.C.; Galli, M.; Rocha, N.A.C.F. Effect of physical therapy interventions on spatiotemporal gait parameters in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 1507–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Tan, Z.; Yun, G.; Cao, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Chen, T. Effectiveness of exercise interventions for children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 53, jrm00176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino-Andrés, J.; García de Mateos-López, A.; Damiano, D.L.; Sánchez-Sierra, A. Effect of muscle strength training in children and adolescents with spastic cerebral palsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2022, 36, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bania, T.; Chiu, H.C.; Billis, E. Activity training on the ground in children with cerebral palsy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2019, 35, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, E.L.; Spencer, S.; Kentish, M.J.; Horan, S.A.; Carty, C.P.; Boyd, R.N. Efficacy of cycling interventions to improve function in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2019, 33, 1113–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ortiz, C.; Gaebler-Spira, D.J.; Mckeeman, S.N.; Mcnish, R.N.; Green, D. Dance and rehabilitation in cerebral palsy: A systematic search and review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2019, 61, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collado-Garrido, L.; Parás-Bravo, P.; Calvo-Martín, P.; Santibáñez-Margüello, M. Impact of Resistance Therapy on Motor Function in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clutterbuck, G.; Auld, M.; Johnston, L. Active exercise interventions improve gross motor function of ambulant/semi-ambulant children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 1131–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, J.M.; Cassidy, E.E.; Noorduyn, S.G.; O’Connell, N.E. Exercise interventions for cerebral palsy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD011660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elnahhas, A.M.; Elshennawy, S.; Aly, M.G. Effects of backward gait training on balance, gross motor function, and gait in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Clin. Rehabil. 2019, 33, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, P.A.; Starling, J.M.P.; Oliveira, V.C.; Gontijo, A.P.B.; Mancini, M.C. Combining balance-training interventions with other active interventions may enhance effects on postural control in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2020, 24, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardımcı-Lokmanoğlu, B.N.; Bingöl, H.; Mutlu, A. The forgotten sixth sense in cerebral palsy: Do we have enough evidence for proprioceptive treatment? Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 3581–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.C.; Ada, L.; Bania, T.A. Mechanically assisted walking training for walking, participation, and quality of life in children with cerebral palsy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 11, CD013114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.G.; Yun, C.K. Effectiveness of treadmill training on gait function in children with cerebral palsy: Meta-analysis. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2020, 16, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, T.; Strøm, V.; Simic, J.; Rike, P.O. Effectiveness of training with motion-controlled commercial video games on hand and arm function in young people with cerebral palsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 52, jrm00012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plasschaert, V.F.P.; Vriezekolk, J.E.; Aarts, P.B.M.; Geurts, A.C.H.; Van den Ende, C.H.M. Interventions to improve upper limb function for children with bilateral cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2019, 61, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathinam, C.; Mohan, V.; Peirson, J.; Skinner, J.; Nethaji, K.S.; Kuhn, I. Effectiveness of virtual reality in the treatment of hand function in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. J. Hand Ther. 2019, 32, 426–434.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoro-Cárdenas, D.; Cortés-Pérez, I.; Zagalaz-Anula, N.; Osuna-Pérez, M.C.; Obrero-Gaitán, E.; Lomas-Vega, R. Nintendo Wii Balance Board therapy for postural control in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2021, 63, 1262–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Loprinzi, P.D.; Ren, Z. The Rehabilitative Effects of Virtual Reality Games on Balance Performance among Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Wu, J. The Effect of Virtual Reality Games on the Gross Motor Skills of Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pin, T.W. Effectiveness of interactive computer play on balance and postural control for children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Gait Posture 2019, 73, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warnier, N.; Lambregts, S.; Port, I.V. Effect of Virtual Reality Therapy on Balance and Walking in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2020, 23, 502–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbanna, S.T.; Elshennawy, S.; Ayad, M.N. Noninvasive Brain Stimulation for Rehabilitation of Pediatric Motor Disorders Following Brain Injury: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 100, 1945–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, A.P.; Pagnussat, A.S.; Pereira, G.A.; Scopel, G.; Lukrafka, J.L. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation to improve gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy: A meta-analysis. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2019, 23, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanon, M.A.; Pacheco, R.L.; Latorraca, C.O.C.; Martimbianco, A.L.C.; Pachito, D.V.; Riera, R. Neurodevelopmental Treatment (Bobath) for Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review. J. Child. Neurol. 2019, 34, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guindos-Sanchez, L.; Lucena-Anton, D.; Moral-Munoz, J.A.; Salazar, A.; Carmona-Barrientos, I. The Effectiveness of Hippotherapy to Recover Gross Motor Function in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Children 2020, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadağ-Saygı, E.; Giray, E. The clinical aspects and effectiveness of suit therapies for cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Turk. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 65, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betancourt, J.P.; Eleeh, P.; Stark, S.; Jain, N.B. Impact of Ankle-Foot Orthosis on Gait Efficiency in Ambulatory Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 98, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milne, N.; Miao, M.; Beattie, E. The effects of serial casting on lower limb function for children with Cerebral Palsy: A systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güçhan, Z.; Mutlu, A. The effectiveness of taping on children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 59, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbadini, G.; Pierro, M.M.; Ferrari, A. La Riabilitazione in Età Evolutiva: Educazione ed Apprendimento di Funzioni Adattive; Bulzoni: Roma, Italy, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Fedrizzi, E.; Anderloni, A. Apprendimento e controllo motorio nel bambino con paralisi cerebrale infantile: Dai modelli teorici alla prassi terapeutica, Giorn. Neuropsich. Età Evol. 1998, 18, 112–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, A.; Cioni, G. The Spastic Forms of Cerebral Palsy; Springer: Milan, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fedrizzi, E. La Valutazione Delle Funzioni Adattive nel Bambino con Paralisi Cerebrale Infantile; Franco Angeli Editore: Milano, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Palisano, R.; Rosenbaum, P.; Walter, S.; Russell, D.; Wood, E.; Galuppi, B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1997, 39, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliasson, A.-C.; Krumlinde-Sundholm, L.; Rösblad, B.; Beckung, E.; Arner, M.; Öhrvall, A.-M.; Rosenbaum, P. The Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) for children with cerebral palsy: Scale development and evidence of validity and reliability. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2006, 48, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzolatti, G.; Fadiga, L. Grasping objects and grasping action meanings: The dual role of monkey rostroventral premotor cortex (area F5). Novartis Found. Symp. 1998, 218, 81–95; discussion 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binkofski, F.; Buccino, G. The role of the parietal cortex in sensorimotor transformations and action coding. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 151, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pellegrino, G.; Fadiga, L.; Fogassi, L.; Gallese, V.; Rizzolatti, G. Understanding motor events: A neurophysiological study. Exp. Brain Res. 1992, 91, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzolatti, G.; Cattaneo, L.; Fabbri-Destro, M.; Rozzi, S. Cortical mechanisms underlying the organization of goal-directed actions and mirror neuron-based action understanding. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 655–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonini, L.; Rotunno, C.; Arcuri, E.; Gallese, V. Mirror neurons 30 years later: Implications and applications. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2022, 26, 767–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, A. From movement to action: A new framework for cerebral palsy. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 55, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoare, B.; Greaves, S. Unimanual versus bimanual therapy in children with unilateral cerebral palsy: Same, same, but different. J. Pediatr. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 10, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerstein, R.; Hoffman, M.B.; Rand, Y.; Jensen, M.R.; Tzuriel, D.; Hoffmann, D.B. Learning to Learn: Mediated Learning Experiences and Instrumental Enrichment. Special Serv. Sch. 2010, 3, 49–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongbloed-Pereboom, M.; Janssen, A.J.; Steenbergen, B.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W. Motor learning and working memory in children born preterm: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012, 36, 1314–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krumlinde Sundholm, L. On the other hand: About successful use of two hands together. Conference proceedings from the Third International Cerebral Palsy Conference. Dev. Med. Child. Neur. 2009, 51 (Suppl. 2), 39. [Google Scholar]

- Iacoboni, M.; Woods, R.P.; Brass, M.; Bekkering, H.; Mazziotta, J.C.; Rizzolatti, G. Cortical mechanisms of human imitation. Science 1999, 286, 2526–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogassi, L.; Ferrari, P.F.; Gesierich, B.; Rozzi, S.; Chersi, F.; Rizzolatti, G. Parietal lobe: From action organization to intention understanding. Science 2005, 308, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramontano, M.; Polo, N.; Bustos, A.O.; Lisi, D.; Galeoto, G.; Farsetti, P. Changes in neurorehabilitation management during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. NeuroRehabilitation 2022, 51, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Faccioli, S.; Sassi, S.; Pagliano, E.; Maghini, C.; Perazza, S.; Siani, M.F.; Sgherri, G.; Farella, G.M.; Foscan, M.; Viganò, M.; et al. Care Pathways in Rehabilitation for Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: Distinctiveness of the Adaptation to the Italian Context. Children 2024, 11, 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11070852

Faccioli S, Sassi S, Pagliano E, Maghini C, Perazza S, Siani MF, Sgherri G, Farella GM, Foscan M, Viganò M, et al. Care Pathways in Rehabilitation for Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: Distinctiveness of the Adaptation to the Italian Context. Children. 2024; 11(7):852. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11070852

Chicago/Turabian StyleFaccioli, Silvia, Silvia Sassi, Emanuela Pagliano, Cristina Maghini, Silvia Perazza, Maria Francesca Siani, Giada Sgherri, Giuseppina Mariagrazia Farella, Maria Foscan, Marta Viganò, and et al. 2024. "Care Pathways in Rehabilitation for Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: Distinctiveness of the Adaptation to the Italian Context" Children 11, no. 7: 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11070852