1. Introduction

Since the concept of active ageing came into force internationally a decade ago, there has been a significant change of course in the education field to develop an idea to meet the current needs of the elderly. This concept implies having a broader understanding of this phase of life (old age) and promoting possibilities of growth in life to contemplate personal development, such as self-esteem challenges, as well as acquisition and consolidation of competencies such as decision-making and full participation in the social process.

This approach is arguably still being contested as a socio-demographic reality since a growing number of older people are better prepared, healthier, more active, and fully participative in society than previous generations. Therefore, today’s elderly population demands a new model of participation and social integrations to fit the new reality in the so-called active ageing framework. So, the traditional social policies aimed at this group do not work. Therefore, a new approach is needed to change the old perspective of viewing the elderly as dependents rather than active agents of their sociocultural interactions and processes (

Moreno Abellán et al. 2017). Following the World Health Organization approach, the authors claim that it is necessary to participate, contribute socially, and be independent based on each person’s abilities for good ageing.

Another powerful concept of the 21st Century that has emerged in Europe is the active ageing factor that focuses on Intergenerational Solidarity, proclaimed in 2012. Based on political declarations, intergenerational relationships are essential in improving interpersonal relationships from socio-political and educational perspectives and other social groups (

PFIZER Foundation 2015). The interaction between different generations entails multi-physical, multi-cognitive, and multiple social benefits (

Martínez de Miguel et al. 2012). Due to the social isolation of the elderly in past periods, their participation in any field in the community has been constrained. However, now under the umbrella of the paradigm of prevailing active ageing, it is necessary to provide a meeting space to encourage solidarity where the transfer of knowledge between generations is possible and where the creation of affective ties of cooperation and mutual aid can occur (

López et al. 2015).

Nowadays, much research is done on intergenerational relationships, and many studies have been carried out on an international and national scale to enhance this concept. However, there are always some stereotypical elements, so it is essential to maintain the sustainable interest of the States in this 21st Century (

Gutiérrez and Herráiz 2009). Likewise, the University of Burgos has overcome stereotypes through intergenerational activities involving social education students and the elderly in Intergenerational programmes (

Palmero 2014).

In addition, other projects in the same sense have been carried out in The United States, such as the one called “Age to Age: Bringing Generations Together of the Northland Foundation in Duluth (Generations United)”, or “Catch Healthy Habits” of the Oasis Institute in Saint Louis (

Oasis Foundation 2015, livelong adventure website). Some university degrees in nursing have also joined intergenerational programmes in Costa Rica (

Quesada and Granados 2005), and Castilla La Mancha University students of humanities participated in an intergenerational programme directed by Larrañaga

Rubio and Cubero (

2017).

Another clear example of good work is the innovative project “Education and Active Ageing”, directed by

Moreno and Pérez (

2014) at Pablo Olavide University in Seville. Social education university students characterise this teaching project, and it makes use of the instrument called “cine-forum”, whose primary goal is to know the retirement aspects. Another point to highlight is the pre test and post test, which the students do to check how the perception of certain prejudices and stereotypes, which they had of the older group, changes. According to the IGP in the university setting, the multigenerational program should also be highlighted. University students were the participants of this program, as were the children in early childhood education and older people.

As a result, it was found that some of the university students improved their perception of the elderly. Nevertheless, the children’s perceptions remained negative, although a short number of them were positive (

Glee et al. 2018).

Concerning age discrimination, the study carried out by

Babcock et al. (

2018) focuses on the implicit perception that children participating in this project have of the elderly, to promote a more positive view of ageing. Regarding collaborative learning between children and adults, the research performed by

Beynon and Lang (

2018) is part of creating real learning contexts to make a change in both generations. Creating such contexts develops other values such as friendship, personal growth, or the revaluation of the elderly for healthy ageing and avoids mere reciprocal learning. Another precise instance of an IGP encourages each generation to keep company with older people by offering a family break that allows for the implementation of intergenerational volunteering (

Hoffman et al. 2020).

Therefore, the current project will succeed if the following objective is accomplished: to promote interaction between different generations from a professional perspective (because the youth are the professionals of the future). Thus, there is a need to work with the elderly.

Hence, this project was started to link university students who study Social Work with the Aging Programs’ administrative institutions. It includes National and Regional Gerontologist Plans that focus on intergenerational relationships. The main objectives for the Elderly Plan are

- (a)

To eliminate stereotypes, prejudices and mistrust between university students and the elderly.

- (b)

To promote social participation among the elderly.

- (c)

To promote awareness and a sense of belonging to the social area through intergenerational life experience exchanges.

- (d)

Finally, to allow future social education workers to put their knowledge, abilities and skills into practice and empower them to work with the elderly.

- (e)

The

ESium Project has its base in the Faculty of Education at the University of Murcia (Campus of Espinardo). The whole project is being carried out in Murcia Region and has 25 participating social centres, mainly those who depend on IMAS and the City Council of Murcia. The project was started in 2009, and it is still go-going. All the information about the project can be found on the Internet via Facebook profile:

https://www.facebook.com/ESium-Proyect-977645052300753/.

Furthermore, current insights proving ways to establish intergenerational relationships can provide the present introduction of this work with new additional knowledge on the main questioned topic in this article. These current insights highlight IPs spotting new groups of people such as those experiencing social risks (e.g., exclusion); the elderly; and youngsters. Not only does this bring risks, it also feeds the constraints of not promoting the term “intergenerational”. For this reason, nowadays, IPs are considered essential and have somehow been enhanced. However, as per the risks pointed out, not carrying out this sort of socio-educational action may decrease possible situations in which the elderly can communicate and socially interact, which might bring about a deficit in social functions (

Martínez Heredia and Rodríguez García 2018).

On the other hand, other risks can be associated with the younger group as prejudices and stereotypes must be continuously accepted by this group from an early age. According to

Zarebski (

2019), any work on the intergenerational topic could not appropriately and objectively be dealt with without dealing with prejudices and stereotypes towards the elderly. Moreover, given the fact that other risks mentioned above are not considered, good previous work on ageing would not be feasible, so both groups could not develop a flexible identity across their lives. Finally, without proposals such as IPs, participants could hardly attain social cohesion and solidarity and individual welfare and empowerment due to being exposed to new knowledge, and physical and emotional aspects involved, in such programmes (

Morcillo Martínez 2021).

In this context, research such as that conducted by

Domínguez (

2012) has concluded that IPs are at risk due to the difficulty of carrying them out for a long period of time, that is to say, there is a current lack of sense of continuity regarding this action that persists in time. Another limitation is that IPs are still recognised as high-value socio-educational resources. Considering all of this, economic risks regarding intergenerational activity will always remain due to either the lack of institutional support by the government or the third sector. Both limitations claim a need for relevant involvement by all the involved participants to pursue the success of intergenerational relationships.

In addition, other new insights suggest the term equality among generations and the commitment to building a new vision for the future. In this way, IPs have become modern approaches concerning active ageing (

Baschiera et al. 2014). Additionally, the acknowledgement of intergenerational relationships is still being developed. This last fact was proved by

De-Juanas et al. (

2013) when they found recent ways to build an operational perspective on these kinds of relationships in the elderly groups participating in their study. In this way, more training on this topic has been claimed to keep getting updated. Moreover, social networking, a current Internet trend, has also covered the term “intergenerational relationships” in such a manner that increasing participation by different kinds of participants has been involved. Taking all of these updates into account, it can be concluded that there is an attempt to avoid possible upcoming risks such as involuntary loneliness. Accordingly, those who already took part in intergenerational action would successfully face such a state and could enhance the quality of their life.

Finally, the digital gap present in our society must be mentioned. Unless precise measures are taken, the digital gap will continue to promote the social exclusion of the elderly (

López Gil et al. 2021). In this sense, IP symbolises an innovative method that provides working opportunities to enhance digital competence in the elderly. Provided the elderly used technology, new ways of establishing different intergenerational relationships would arise, along with updated teaching and learning methodologies as a working service of the community or society. An innovative instance is digital mentorship programmes for young people to motivate and engage the elderly using 21st-century technologies, portraying active ageing.

2. Materials and Methods

Due to the methodology used, the present research has been conducted successfully. However, participatory action research has been vital as the primary method. According to

Merriam-Webster, Incorporated (2020), this method involves participation when having a part or sharing in something along with an action when an alteration is brought about. Remarkably, the proposal is based on a model of socio-educational activity that focuses on the participants’ active leading role in promoting interaction and equal generational independence to allow the elderly to live a full life without discrimination due to their age.

Furthermore, this investigation takes action by making participants protagonists of their own educational experiences, such as the work of collectives. Then, the participatory and action process has allowed the research participants to acquire knowledge, abilities and skills in a meaningful setting. Thus, the participants have been provided with relevant experience that has led them to their personal and social development.

Additionally,

Creswell (

2014) affirms that the present method used is related to mixed-method studies as qualitative and quantitative techniques have been utilised. Furthermore, because this research focused on a social issue, such methods have been crucial to finding a solution. In the same sense, this author identifies action research as practical and participative. In addition, this sort of research is characterised as flexible due to the possibility of making adjustments during the research process (

Creswell 2014).

However, it requires involvement in the situation or context of the study to gain real insight into the problem that leads to relevant data collection. Data analysis and a final report based on results were finally completed. Since this was done, the central part of this practical and participatory method occurred by taking action with an intergenerational programme. Furthermore, the investigators, who supported this, still gathered data throughout the process. Finally, the conclusions and new hypotheses discussed have been a prominent source of feedback for future action (

Hernández et al. 2014).

In the same way, a new initiative has arisen to try and find some space for social participation, to bridge the intergenerational gap between the young and old. It involves a great range of methodological strategies: round-table conferences, cinema forums, café meetings, debates, and collaboration with the elderly, during workshops in which people at university can contribute to institutional centres. Workshops are also carried out in elderly social centres, which allows them to contribute to their skills and ideas in voicing their views or sharing their life experiences. The main activities are done via forums such as seminars, monographic workshops, meetings, and exchange conferences, on topics that affect youth and the elderly.

Intergenerational round-table conference

The First Meeting for the Elderly occurred on 11 May, 2009, and it consisted of five representatives from older people’s centres and three students from the social education discipline. Some working sessions had been established before to prepare the contents later developed at the round-table conference to have representative participation for all. That first experience was widely approved by participants, and hence it marked the starting point for the development of the project today.

Cinema forum

Intergenerational cinema forum has been one of the activities carried out. In this case, young people are the ones that move to the older people’s centres to share the proposed activity. The proposals for the content have been varied: films related to intergenerational topics and specific topics on ageing and general issues.

The elderly collaboration is paramount when teaching university subjects on matters of collectivity

Social Education for the Elderly is taught during the second course (first term) and the third course (first term) of the Social Education Degree to allow students to collaborate within different contents. However, there has been a wide range of options in recent years, such as Socio-Cultural Animation and Development, also taught during the third course of the Education for Health Degree and Education through Arts Degree, trained in the fourth course. In addition, other fields are included in the Master subjects of Adult and the Master of Senior Education in Inclusion–Exclusion within the Faculty of Education, which addresses the issue of new technologies as a factor of social exclusion.

Workshops where students of Social Education can contribute to the Imas centres in the Region of Murcia with their knowledge

This activity consists of working in workshops and reaching common conclusions at the end of the conference for the older people in social centres (IMAS) and the education students at the University in Murcia.

In this case, the workshops would be designed by social education students where both the elderly and the youth can play leading roles when dealing with the philosophy of socio-cultural animation and by using qualitative strategies in group work activities. The idea is that every generational group can reflect on the topic being discussed in various ways by sharing their social and personal life-long experiences, sharing expectations, breaking barriers to stereotypes, and facing life challenges. Furthermore, many issues can be discussed and dealt with during the sessions by organising working groups through workshops. Once the workshop is finished, a conclusion will be held to agree on how meaningful or engaging the activity was to get feedback for future work forums.

In that sense, the following topics have been addressed as contents of research projects: emigration, new technologies, health, family, stereotypes, and cultural traditions, among others.

Come and meet us

Due to the high demand for bigger spaces for intergenerational interactions, a new initiative emerged in 2012, with an activity known as Come and Meet Us. The main goal of the training is to allow different collaborating centres within the project to organise an intergenerational program to prepare the youth workshops in these centres, where the youth can have leadership roles or get involved in the centre projects. For this reason, young students visit those special centres to get to know what a centre for the elderly looks like. Social exchange can deepen sociocultural values through the activities developed in these centres.

New ways of communicating

According to the European Year for Active Ageing and Intergenerational Solidarity, new ways of communicating were set up with a video workshop created in 2012. The workshop’s main aim was to create a video that included the elderly, university students, and professionals who had participated in the University Intergenerational Project during the previous four years. The organisation of such a video entailed an intergenerational experience organised by a team that comprised all three participants in the workshop. Furthermore, the shooting of the short documentary film “Heroes” in 2015 by Isabel Coixet Spain in a Day helped highlight the circumstances and situations that people face in our country.

In 2019, an innovative educational Project called “An Achieved Dream and Intergenerational Tales” was conducted. Such a project influenced older people to teach and improve handwriting skills. It was possible thanks to the social education students at the University of Murcia, who helped this group of people.

From an intergenerational perspective and through different meetings, talks and conversations, the foundation, which gives literary meaning to people’s life stories, which have a lot to tell us, was getting built. The magic created in the personal interrelation made the memories, thoughts and fables flow. What happened was so authentic and genuine that it was difficult to define it while making it. Thus, these texts try to turn the story of their life trajectory into an extraordinary tale, to which figurations, metaphors and resources for creative writing have been added.

Additionally, they comprise stories for grandchildren, children, neighbours, uncles and aunts, and male and female students. So, they also become a memories their lives and a heritage legacy for the future. The year 2021 was characterised by an online meeting in which adults and young people had the opportunity to reflect on the consequences of the pandemic caused by COVID-19 and the conditions they lived in. In the same respect, working on new technologies and their advancement is the beginning of the digital divide and involves designing educational actions while considering the fundamental skills and needs of the participating older people.

The Assessment of the Project

The key points to emphasise are an analysis of the facts and the evaluation of the process, which includes the intergeneration assessment of the participants in the project that was developed by the Faculty of Education at the University of Murcia and the social centres for Elder People of IMAS (Murcian Centre of Social Action). The method utilised in the present research is descriptive and exploratory.

This mixed approach has been supported by a Likert-type scale through the use of a questionnaire to gather data related to four main axes: reduction of stereotypes about age, the increase of intergenerational knowledge as well as professional knowledge for students, professional publicity, and personal satisfaction concerning the methodological model of participation within a university context.

Moreover, the scale included items that showed different responses to be marked by the participants, such as 1 (none), 2 (a little), 3 (considerable), 4 (quite a bit) or 5 (entirely). Thus, all four areas have been evaluated to get to know the effectiveness of the project. Additionally, techniques such as discussion groups or focus groups and an interview were utilised. In addition, they all took into account data related to personal details of the project participants through questions about age, sex, group identity (student or older person) and place of provenance (university or social centre).

According to

Bernard and Ellis (

2004), the evaluation of an IGP designates the role of the responsibility of the involved subjects in this project; volunteering; intercommunity dissemination; and comparison with other projects as guides for its implementation. At the same time, it is a tool to analyse the impact on society and confront ageing challenges, such as the fight against stereotypes, ageism, avoiding isolation and loneliness, and improving the perception of the elderly.

In a few words, the evaluation process must be an element of equal importance to the other aspects that an IGP encompasses. Thus, it is essential to analyse which parts work and which do not. When assessing, enhancement and knowledge are provided in the intergenerational field by carrying out such analysis.

Participants

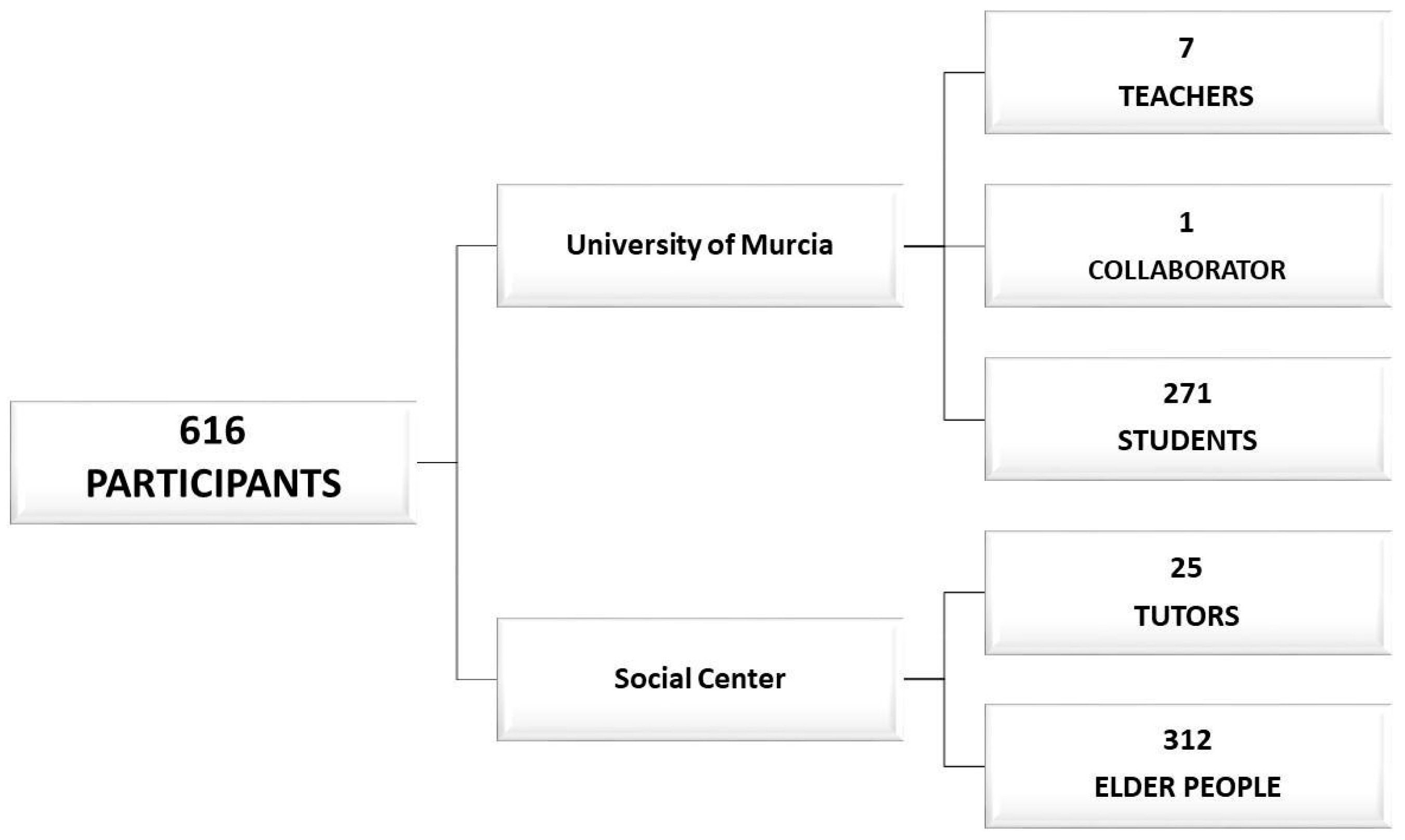

There were 583 people participants in the questionnaires. Precisely, 271 were students and 312 were older people. In addition, there were another 25 participants, particularly professionals, who were interviewed. Therefore, the total number of people who participated in this project, including teachers, was 616, as shown in

Figure 1.

The ages of the participants vary as

Table 1 shows, where the ages are grouped by frequency in such a way that the age category ranged between 19 and 88 years (M = 21, 7, SD = 2.8), and the average of the elderly was close to seventy years of age (M = 69.0, SD = 6.6).

Regarding gender participation, the most extensive participation was represented by females with 75.8% compared to 24.2% for males. *Older women participated more often than men did in educational activities. The same for the social education students, yet there was a vast difference here in terms of the number of men who participated. It should be noted that both genders were represented, and the distribution of the group of students included 104 women (90.4%) and 11 men (9.5%). In contrast, the older group was represented by 60.7% women and 39.2% men.

The evaluation of the project took into account specific qualitative results throughout the constitution of two groups of discussion: one formed by 25 elder people (men and women) who were veterans the project, and another one by students of social education (25) who had participated in some of the activities in the previous academic courses. Moreover, 25 interviews were done with critical people, the directors and technicians of the centres for elderly people of the Institute of Social Action in Murcia. Such interviews took place at the University of Murcia, and the discussion groups took place at the IMAS centres in the Region of Murcia (17).

3. Results

The first objective was: try to eliminate stereotypes, prejudices, and distrust between university students and elderly people. The breaking of stereotypes between older and younger people has been achieved (4,16).

Based on the positive results obtained, the participants are a clear example of the intergenerational project’s possibilities. Furthermore, this shows the negative stereotypes that reciprocally exist between old and young people. It also illustrates the belief that educational activities allow people to exchange opinions, modify false beliefs, and improve intergenerational knowledge.

Thus, the following results and sets of data were obtained where the sample expressed had the following opinions with maximum scores: 83% of the model believed that the experience had contributed to breaking stereotypes of each other (item 1), and 88 % stated that the incident has had allowed them to have better knowledge of the two groups (item 2). These results indicate that most participants strongly agree that the project reduces the distance between generations and is both at the belief and knowledge level. Hence, the risk aversion and risk intolerance among the elderly and the young may be reduced as a result.

Regarding the second objective—to promote the elderly’s social participation—these sorts of programmes are recognised to promote equity of social participation of older people in respect to the rest of the age groups. This objective also claims a call for attention to the necessary creation of spaces for active participation. All social institutions must play a primordial role in their development and promotion in the more open-minded society of the 21st Century.

Nowadays, the fact that the potential of the older group is huge after retirement is proved by the fact that these people are increasingly getting more well educated and gaining experience. Furthermore, the involvement of these kinds of proposals makes the perception of volunteering more inclusive. It also allows people to participate in cultural, economic, political and social life in the same way the other generations do.

Apart from that, it is found that intergenerational programs are a crucial element of the educational work done by the interviewed professionals. Besides, it would be essential to increase the number of actions based on two key aspects. On the one hand, the decrease of institutional isolation usually characterises centres for the elderly and opens the centres to the community, avoiding the intergenerational gap. On the other hand, the enrichment and the exchange of resources and valuable learning encompass intergenerational experiences.

Concerning technical aspects of the evaluation, institutional planning and coordination should be considered essential. A study on needs, realistic timing, and the impact caused on society is a challenge to face the active aging process. To be clear, older people look for new personal and group development ways to remain active. This group of people wishes to continue their education, to face isolation and loneliness, which allows for new ways to establish relationships that improve their quality of life and the social responsibility of all participating subjects.

The third objective aims

to promote the elderly’s sense of awareness and belonging to the social area where they live, especially by exchanging life experiences and common goals from generation to generation. Evaluation results show that these groups developed the different intergenerational activities of the project, as the table shows (see

Table 2). So, generally, the results were valued as positive and very satisfactory; as such, the assessments could be considered positive on both sides (4.27 out of 5 points).

As a result, the evaluation reveals the effects and achievements of the IGP in the participants, the professionals, and the community or the university setting studied. Concerning the elderly, the review also shows students’ mindset of this group of people and their social commitment. Regarding young people, it is necessary to investigate their perception of the elderly to know about certain stereotypes and improve their responsibility and social skills as future social educators, and the interaction with other generations at the community level.

Furthermore, the analysis of the community environment to face social relationships found during the program should be considered in the assessment of this project, in addition to advantages and disadvantages, proposals for improvement before the design, and coordination and implementation for upcoming programs.

These were the aspects deemed by the participants as entirely satisfactory (4.38), giving the perception that the experience has made intergenerational knowledge better.

The results are based on the last objective: to make the abilities and skills of future social education workers possible, when needed to empower them with the knowledge and provide areas where they can develop their skills and put what they learn from working with the elderly into practice. Regarding the use of spaces, structures and participatory methodologies in the field of the university institution (item 4), 94.1% of the participants considered the proposed objective to be appropriately favourable. Moreover, the participants gave a high average rating (4.67) to the option that allows social education students to get more involved with the elderly.

Regarding the professionalisation of the social educator, the experience and activities carried out by the students studying a Social Education Degree is valued in a very positive way. In fact, 96% of the participants believe that it allows students and seniors to obtain a better mutual connection and establish a professional relationship (item 3). Likewise, most of them think that the project reciprocally influences both generations, just as they value the chance that the university and social institutions have to make the meeting between seniors and the youth possible. Furthermore, there is a (4.51) participatory rate since they are technical promoters of the social bond during intergenerational activities, providing them with more excellent knowledge of the social methodology.

Finally, regarding the intergenerational project, 100% of the students consider that introducing the project as a teaching and a methodological strategy of innovation in the university context is a positive element. Yet, there are some aspects to be highlighted, and they are structured into four categories:

- (a)

More outstanding knowledge of the field (51.28%): see the changes they have endured during their life and take them into account for the future (ES12); gain first-hand knowledge about the collective... (ES8); to better know the group of older people and, in the future, to be able to dedicate myself to this (ES26); thanks to the project, we working with the collective is now possible, we know their needs and expectations, and we can think of work options (ES33).

- (b)

It allows for contrasting perspectives, and similar or different experiences (43.58%): Yes, it is an excellent method for understanding and sharing experiences, different points of view, and ordinary things. Indeed, we realise that the differences between some ages and others are neither so tremendous nor insurmountable (ES 5); this project allows one to get to know the elderly from another perspective, and it can be proven that we have more things in common than we think thanks to these shared spaces (ES50).

- (c)

It favours an intergenerational approach (38.46%): yes, because it helps to relate different generations (ES25); because it promotes knowledge and getting closer to the elderly and it reduces prejudice (ES13); yes, because students learn from the elderly and vice versa (ES27).

- (d)

It allows for the acquisition of strategies and skills to work with the collective (20.51%): new experiences and more excellent knowledge, which allow me to look for new methods and ways of working with them (ES1); it is through everything I have learned I can enrich my knowledge and also use what has been developed in future workshops, activities or intergenerational meetings (ES66); we learn new methodologies, tools and work techniques … ES10).

To a lesser extent but in a significant way, some students consider that it allows them to grow professionally (10.25%): more remarkable professionalism (ES7); it provides us with experience and enthusiasm to continue working with this group, as well as contributing to personal enrichment in addition to the professional (12, 82%): … nourishing me personally (ES8).

In general, as indicated previously, they add significant value to the introduction of the project and as a methodological strategy in the classroom. Therefore, their main demands are proposals to improve or increase activities to increase their duration with work sessions and have better organisational conditions with larger spaces and smaller workgroups to reinforce the intensity of interactions.

On the other hand, for the elderly, being able to participate in the university context is a highly valued experience that contributes to the reinforcement of their self-esteem and compensates for their unfulfilled educational expectations, in many cases since they could not access these types of studies in their youth.

Regarding technical aspects of evaluation, it is essential that adequate planning and institutional coordination be carried out, in addition to contemplating study necessities, realistic timing and highlighting the impact caused on society. That is a future challenge in the active ageing process: yes, it is to get a better approach and learn practically (P5); yes, because these activities enrich and convey many new ideas (EPF18). Moreover, most of them know intergenerational experiences: yes, through my university training and in activities in my closest environment (P3).

Another aspect marked by professionals is the importance of mutually enriching each other and making exchanges: it is necessary to share, live and create friendship ties regardless of age, sex, social condition, etc. I learn from you and you from me (P1). The largest group of responses is associated with the great relevance of the intergenerational relationship in today’s society: society’s approach is related to all ages (P6). Action for social improvement and the need to end up with stereotypes are also significant. These two last elements can be helpful to solve social problems as instruments: ending up with stereotypes related to the elderly (P25).

The last dimension provided by professionals is related to the quality and importance of the evaluation of an IGP: good planning and respecting the time required to prepare the activity (P19). Likewise, coordination is essential: clear and defined inter-institutional coordination (P4). The third factor is associated with the participants’ satisfaction and, therefore, their increase in continued editions: the specific activity in which it takes place is attractive to the participants and is original and fun (P17). Finally, other less cited factors are associated with the belief in the benefit of the program: above all, motivation (P21).

4. Discussion

This University Intergenerational Project focuses on the problem of the generation gap (between the young and the elderly) who are at risk of exclusion, loneliness, isolation due to problems, and the stress of following social rules. Additionally, it highlights the fact that social education can become a crucial point when dealing with socio-educational work with elderly people since social education promotes dynamic action in an intergenerational way. So, it is possible to set up stable and personal initiatives to improve the conditions and people’s quality of life through participation, such as the study on collaborative learning directed by

Beynon and Lang (

2018).

There is proof of relevant intergenerational contributions such as solidarity, cohesion, social reproduction, and life maintenance, from a reflective perspective (

Moreno et al. 2018). However, prejudices and stereotypes towards the elderly are still present in our society (

Escarbajal De Haro et al. 2015). This topic is a bullet point and engages a conflictive way of thinking. According to

Salvarezza (

2019), old age can be a concept that is not kept in mind consciously and changes with educational, relational, personal and sociocultural history due to its expectations. Such expectations arise during infancy and develop throughout one’s life (

Zarebski 2005).

Hence, the educational intervention in this project shows how the elderly can get more involved in educational activities so that they are provided with new opportunities to participate and socially contribute to the promotion of active ageing. The same results were obtained in a project called “Age to Age: Bringing Generations Together of the Northland Foundation in Duluth” (

Northland Foundation 2008).

Likewise, these sorts of activities have been carried out in the same way as the present research’s, and both showcase a teaching–learning process that links the elderly with the young. Thus, they correspond to the results obtained in the study conducted by

Baschiera et al. (

2014). Additionally, some values are given particular importance, such as individual and social responsibility, which relate to the previously studied research concerning overcoming stereotypes.

On the one hand, most older people participate in the project for the first time by using their own experiences based on the contents of a subject matter, whereas others may be mere viewers. On the other hand, due to this project, young people and the elderly have started to take on new roles in social and educational activities in a specific setting, for example, at universities or in social centres, as both intergenerational groups acquire knowledge and experience from each other. Another instance is the University of Burgos, which has experienced the overcoming of stereotypes and a willingness to join intergenerational activities among social education students and the participating elderly in intergenerational programmes (

Palmero 2014). Castilla La Mancha University conducted the same activities with humanities students who participated in an intergenerational programme directed by Larrañaga

Rubio and Cubero (

2017).

Additionally, the current project developed in 2009 at the University of Murcia has generated excellent results concerning the number of participants and the quality of experiences. Consequently, it has been rewarded with the European International Award of Social Innovation SIforAGE. The key to success has been age, which has allowed groups of people from a wide age range to work together. Working with the elderly and university students is essential for discussion and reflection. In this sense, the IGP called “Sharing Childhood”, suggested by

Orte et al. (

2016); the collaborative proposal by

Salmerón et al. (

2019) for the elaboration of a storytelling book spanning generations; and a research project to build intergenerational relationships, directed by

Gradaílle et al. (

2021), have achieved similar purposes to those that the present participatory action research focuses on.

Moreover, all the dynamic actions proposed in this project are promoted through fun sociocultural strategies, which pedagogically facilitate more social readiness of both participating parties. On the other hand, coordination between professionals and institutional workers from two institutions of the Region of Murcia, that is to say, the University of Murcia and the Institute of Social Action (IMAS), has been necessary to set up the project’s activities.

Additionally, the project is correctly assessed by all participants, aiming at the expansion of the project and the reinforcement and improvement of its core elements. All in all, it has become a benchmark for intergenerational action in the Region of Murcia. The project emphasises the need for social education and how fundamental it is to reinforce alternative socio-educational work with older people. Social education can overcome the gap between intergenerational groups in a very stable manner. This last fact mentioned is supported by intergenerational experiences at the University of Burgos that highlighted the figure of the social worker (

Palmero 2014).

Therefore, socio-educational work will be a big challenge in the 21st Century since it involves working with the elderly to promote active ageing and intergenerational relationships; to grant value to the figure of the social educator within the interdisciplinary teams of all the socio-educational care services; to provide classrooms for the elderly, and social service centres; and to encourage older people themselves to participate in self-acceptance workshops as an educational ‘resource’ in the different teaching centres, which coincides with other research carried out by

Calvo de Mora (

2014).

These challenges are consistent for some elderly participants of the sample in socio-educational activities, which coincides with other research carried out on this subject by

Pinazo and Kaplan (

2007),

Rodríguez et al. (

2013) and

Bagnasco et al. (

2020). Likewise, the results of the study are also related to the progressive demand for the realisation of learning courses, which is included in the paper by

Abellán and Esparza (

2009), or the work done by

Montero et al. (

2011), which shows high motivation among some elderly participants in the sample.

Finally, we must also emphasise that this research has been supported by The SIforAGE Project of the European Union, which financed its development (Project Code 25232: Active Ageing and Intergenerational Solidarity as an Example in the University Context). Furthermore, this project was awarded the “Prize for the Promotion, Participation and Inclusion of Older People” in 2019 by The Institute of Social Action in the Region of Murcia (IMAS).

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, by doing this project, we have shown that people’s open-mindedness toward others is significant. It has become one of the critical aspects of maintaining social balance. Likewise, creating an intergenerational project at the University of Murcia could help society because this project could promote social integration through intergenerational relationships by showing a more positive image of aging and adapting the educational system to social, economic and demographic changes in Spain. At the same time, this project could expand to other international contexts to promote the figure of the social educator and other work-related professions. In short, aging is an integral part of life, so we need to accept the reality within the demographic changes that our elderly population goes through.

Therefore, the current project plays a crucial role in creating new relationships and promoting intergenerational interactions. Not only does it enhance the participants’ perception of their own identity, it also provides a roadmap that shows them how they can contribute to society. For instance, young people may change their opinion about the elderly when they can become active agents by learning from their experiences. In this way, citizens should consider the prejudices and stereotypes that are very present in today’s society due to cultural socialisation, as shown in the project carried out by

Moreno and Pérez (

2014).

Furthermore, the social setting is a challenge for a society that citizens should face together, along with state institutions that do not consider social inclusion. Nonetheless, projects such as the present one may force these institutions to get involved in satisfying the needs of society so exclusion related to the elderly can be avoided (

Babcock et al. 2018).

Accordingly, governmental institutions should develop social cohesion rules to make necessary changes to face these social challenges. The intergenerational programs are an excellent example of alternative solutions that help people perceive the family; culture; and technology. Therefore, institutional recognition of a social educator is vital in facilitating intergenerational social-educational work. This can be achieved within the interdisciplinary professionals’ framework, where roles are already socially and institutionally recognised (

Martínez de Miguel et al. 2016).

In this sense, our results show that society has somehow been boosted as a community and has helped citizens develop a democratic spirit in which people at different stages are involved. Thus, we can conclude that the elderly generation is fond of knowledge for the younger generation regardless of economic factors and vice versa. Instead, the involvement of this first group has been found to be a means to maintain relationships that allow for common welfare. In this way, there is a call for social action that promotes prosocialism (

Lombardi 2018). The experiences proposed in the research project have also been found to be relevant for developing a united community.

However, gerontology must be studied to understand connections between generations, and the repercussions of running a project such as the present one should be under consideration. In addition, the analysis of results highlights a realistic and optimistic insight into aging and welfare that is in contrast with health problems that lead to a negative perception of aging (

Barranquero and Ausín 2019).

Another problem was that the elderly, when reaching the last stage of their lives, had reduced expectations of their development and progress, whether educational, emotional, spiritual, or intellectual. This may be due to the unfavourable contextual and socio-historical factors that arose within the Spanish society in the first half of the 20th Century (

Pérez and Abellán 2018). However, the participation in activities such as those carried out in the present project somehow proves that the elderly’s expectations may improve for the better.