1. Introduction

Creative accounting is associated with information engineering and financial reporting, since it is frequently practiced to disclose financial information in a way that makes it appear better than it would have if stated honestly (

Qian et al. 2015). Accurate, relevant, and trustworthy disclosures are considered to be a way of improving the image of a business, lowering the cost of financing, and increasing the marketability of shares. It also simplifies the purchase of long-term funds, allows management to properly account for the resources entrusted to them, and works as a catalyst for the expansion and development of the capital market.

A previous study revealed four key variables of creative accounting: ethical considerations, disclosure quality, internal control, and ownership structure (

Škoda et al. 2017). Whether or not these determinants apply to financial reporting remains to be confirmed. As a result, the purpose of this research is to assess creative accounting by measuring the degree to which creative accounting is entrenched in bank financial reporting. Moreover, the causative factors that motivate banks to indulge in creative accounting are also assessed (

Yaseen et al. 2018). Prevailing accounting procedures enable a certain leeway in the application of accounting principles (

Kalbers 2009). Professional judgment is applied to define recognition standards, measuring procedures, and the accounting body’s character. When making such decisions, executives may purposefully withhold important facts or mislead accounting data in order to reflect a favorable financial condition. Profits may be stated as higher in order to increase attractiveness, or lower in order to reduce tax burden. It has been reported that accountants use their domain expertise to falsify financial information and reporting for organizations, a practice known as creative accounting (

Goel 2014).

Financial reporting focuses on providing stakeholders with the reliable, accurate, and timely financial data that they require to make decisions regarding bank operations (

Chang et al. 2019). The goal of financial reporting is to communicate financial data to users so that they can make informed and objective decisions. Nonetheless, contemporary accounting policy allows for a lot of flexibility in accounting procedures and the application of objective judgement to set measurement rules, recognition criteria, and, in some cases, the categorization of the accounting body. The ability to pick and choose which accounting components to use allows for deliberate data manipulation or concealing. Such manipulations can increase a company’s perceived desirability by making the company appear more profitable and financially stable than it actually is. Such practices can mislead users and investors by using disinformation, which is a significant hindrance to corporate growth and investment mobilization (

Campello et al. 2011;

Jedi and Nayan 2018). Indeed, financial reports provide direction to users who rely upon these reports for objective decision making (

Vladu et al. 2017).

However, there is limited evidence on how creative accounting determinants impact the quality of financial reporting. This research focuses on two main questions:

2. Methodology

As aforementioned, the present critical review of the previous studies the correlation between creative accounting determinants and financial reporting quality in the financial sector to be identified (

Ramadan 2017). Along with reviewing relevant research and discussing emerging financial sector difficulties, we also advocated the incorporation of creative accounting determinants into their working culture to find the competitive market advantages and boost productivity (

Kovalová and Michalíková 2020). In order to answer the posed research questions, an in-depth analysis of the existing studies was conducted based on the effects of creative accounting determinants on the financial reporting quality (

Al-Natsheh and Al-Okdeh 2020;

Martin et al. 2019). The identified ongoing debates related to the importance of implementing creative accounting determinants in the organisation and its effect on the financial reporting quality provided new insight and opened up avenues for further studies (

Brauweiler et al. 2019;

Iqbal et al. 2015). There is no better source of unbiased summaries and interpretations of study findings than peer-reviewed journals (selected issues based on expertise) (

Manes-Rossi et al. 2020).

Generally, the present systematic review is based on a logical and precise framework that is reproducible and can serve as standalone document (

Massaro et al. 2016). It allows for the logical mistakes and biasness that originate from subjective analyses and opinions to be minimized. Scientifically, this study is critical, since it provides a basic understanding of previous research and adds fresh information to the database, highlighting issues and potential trends (

Pedro et al. 2018). It is because of this that accounting, management, and financial studies review papers have received increased attention (

Massaro et al. 2016). The banking sector worldwide has been experimenting with a new accounting determinants format in an effort to improve their financial reporting. Motivated by the significance of the implementation of creative accounting determinants in the financial sector, as advocated in various recent studies (

Matica (Balaciu) et al. 2014;

Martin et al. 2019;

Ramadan 2017). According to the technique outlined above, this paper followed a three-step process.

As a first step, a comprehensive literature search was conducted, during which relevant publications (published in English and subject to peer review) were selected, critically evaluated, and ranked in accordance with predetermined criteria. (

Cuozzo et al. 2017;

Manes-Rossi et al. 2020). Data were gathered from several databases, including Scopus, Science Direct, Emerald and Web of Science, in the years between 2015 and 2020. In this era, only a few publications were published in the fields of social sciences, business management, finance, and accounting. To retain the high quality of peer-reviewed journal publications, the study area was further limited (through rigorous inclusion and exclusion criteria) (

Julian and James 2009). Research reports were eliminated from this assessment, since they were not included in the other cited resources. These criteria can increase the worth and quality of judgment when examining the current contributing efforts, as previously acknowledged (

Keune and Keune 2018). From multiple databases, 473 documents were retrieved. In addition, these contributions were personally examined to remove any duplication, and 332 were selected. Examples of the inclusion criteria are shown in

Table 1.

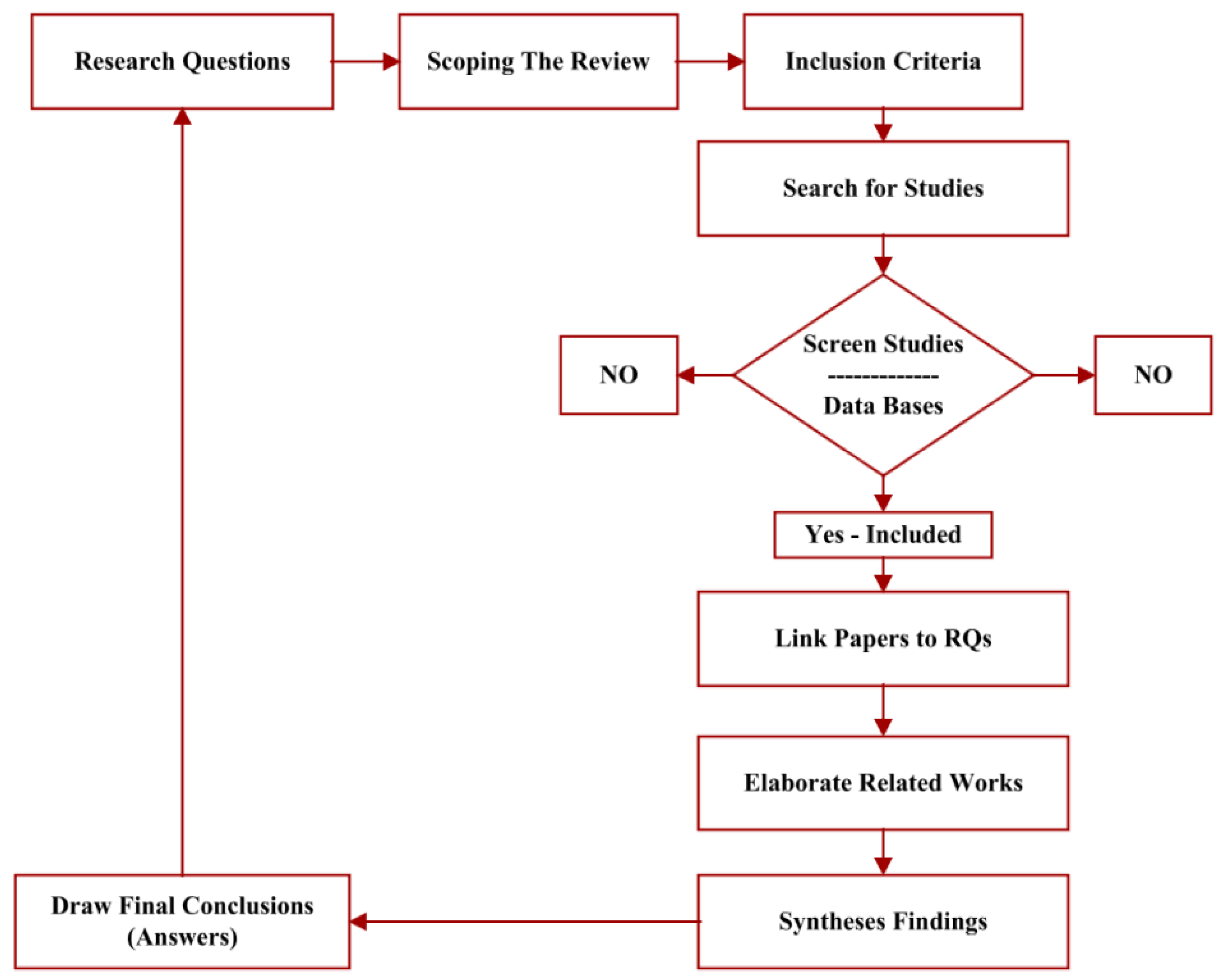

The recovered publications were then appraised for their relevance based on their titles, abstracts, and content using certain established criteria. A total of 233 articles were omitted from consideration due to their focus on a financial-sector-specific innovative accounting determinants format. The SCImago Journal Rank was also taken into account, which resulted in the rejection of another six manuscripts. The third stage was devoted to improving the sampling process. An additional 14 articles were found after a thorough review of the top financial and accounting journal publications. To weed out some of the lesser-known publications, another full-text filter was applied, resulting in 98 papers meeting all of the requirements for inclusion. To summarize, for the purposes of this work, a total of 98 publications were critically examined. Several steps of the review process are depicted in

Figure 1.

3. Creative Accounting

Widely considered the father of accounting, Luca Paciolo first introduced the concept creative accounting more than five centuries ago. Summa de Arithmetica, in 1494, was the author’s first accounting manual, in which he introduced the practices concerning creative accounting. Recently, accountants, auditors, academics, and other researchers have paid much attention to creative accounting. Such practices originated during the industrial revolution and have continued since then; however, creative accounting has significantly increased since the 1980s (

Sanusi and Izedonmi 2014). It had been shown that creative accounting comprises manipulating how revenue is recognised and expenses are accounted for (

Susmus and Demirhan 2013). Such practices lead to the company appearing better on paper than it truly is. Creative accounting does not violate the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). Along these lines, the work of (

Goel 2014) opined that the intention of creative accounting is to project more robust financials as one goal. On the other hand, these practices are also used to project a weaker financial position depending on how the management’s desires. Creative accounting is a critical challenge that has been the cause of major financial crises (

Mudel 2015).

Furthermore, (

Diana and Beattrice 2010) deemed that creative accounting was the set of actions used by managers to represent financial reports with the aim of misleading stakeholders about the company’s financial performance or influencing contractual outcomes tat are dependent on the number reported by the company. Thus, the fundamental question concerns the intent to influence contractual outcomes or mislead stakeholders. It is clear from the discussion that executives deliberately practice creative accounting to characterize their revenue, profits, assets, and other financials to suit vested interests rather than reflect the business’s precise financial position. Such activities are typically conducted in two ways—showing higher or lower profits in the present period at the expense of previous or future accounting periods. Companies’ earnings are significantly impacted by creative accounting; therefore, this subject is critical for regulators, auditors, researchers, and investors.

Moreover, creative accounting comprises the manipulation of both performance indicators and the financial position of the business. Some researchers did not reach an agreement on this view; they consider creative accounting a “deliberate intervention in the external financial reporting process” to benefit specific stakeholders (

Shah et al. 2011). The information that is disclosed does not need to be fraudulent; however, the facts are twisted in a way that can be considered a violation of the “full disclosure” requirement defined by the International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS). The manipulation of accounts is the deliberate change and falsification of financial data to meet the management’s objectives. Typically, the intention is to work as per the management’s expectation or deceive stakeholders by projecting a healthy financial position to outsiders. The manipulation categories of accounts are classified into two different groups: creative accounting (accounting legitimacy is maintained) and accounting fraud (accounting policies and principles are violated) (

Paolone and Magazzino 2014).

3.1. Motivations behind Creative Accounting

Numerous studies have assessed management’s motivation to pursue creativity in accounting (

Akpanuko and Umoren 2018). Nations with conservative accounting frameworks witness conspicuous income smoothing owing to the substantial value of their accumulated provisions. Big bath accounting is a bias that may be present where a loss-making business reports higher than actual losses in a specific year in order to offset losses for subsequent years. It was shown that if there is a substantial difference between real business performance and analyst projections during capital market transactions, creative accounting may be pursued (

Gupta and Kumar 2020). It is feasible to keep the stock price stable or inflated using creative accounting to show a reduction in apparent borrowing. Reduced borrowing projects healthier profits and reduced risk.

Consequently, a company can borrow public money by issuing shares, use the stock for acquisitions, and hinder takeover by other companies. If a company’s directors engage in ‘insider dealing’ concerning the business’s shares, it is possible that they can defer information release using creative accounting; hence, insider trading may be misused for personal gain (

Malik et al. 2011). It should be understood that fancy superficial accounting changes are unlikely to fool analysts in an efficient market. Creative accounting is easily spotted by careful analysts, who see through the income-boosting measures and flag them as potential weakness indicators. This section is split into four subsections highlighting the primary motivators to use creative accounting in financial reports.

3.1.1. Agency Problems

Agency problems are among the key motives that promote creative accounting. Bankers seek profits at the expense of the stockholders. Agency problems lead the management to obstruct and change financial reports. Unfair and unethical accounting practices are frequently used to present a false perception about the business for personal benefit. This interference from a company’s management in the disclosure of financial information negatively impacts the quality, content, validity, and reliability of these statements (

Vladu et al. 2017). It was asserted that the incessant abuse of creative accounting has caused numerous banks to collapse due to improper and low-quality financial reporting (

Arnold and De Lange 2004). The skepticism surrounding the finance and accounts of a company leads to reduced investor confidence; consequently, investors are cautious when investing in Arab or global capital markets because they perceive high risk.

The link between agency problems and the use of creative accounting was presented by the authors of (

Škoda et al. 2017), who indicated that managers are inclined to meet business targets that fetch lucrative bonuses. Some researchers indicated that reporting higher-than-actual profits is a significant driver of creative accounting by managers (

Tunji et al. 2020). Furthermore, managers are attracted to creative accounting because financial rewards such as bonuses and salaries may be much higher if such practices are used. Although researchers have not assessed the effects and incidence of agency issues on creative accounting, there is a consensus regarding the correlation between personal benefits and agency issues, prompting managers to resort to creative accounting (

Saleem 2019).

3.1.2. Executive Reward

There is a significant body of knowledge that attributes financial bonuses as a trigger for creative accounting practices. A poor business performance affects managers’ remuneration and incentives, thereby prompting them to use creative accounting to manipulate financial statements (

Škoda et al. 2017). The boundary separating organisational objectives and the manager’s objectives is narrow. Nevertheless, several researchers have asserted that financial incentives are tied to business performance and shareholder earnings; therefore, these two factors prompt accountants to resort to creative accounting.

Financial reports may be manipulated because contracts and target-based bonuses are correlated with stronger financial reports (

Alit 2017). The executives’ remuneration agreements serve national and international businesses (

Cardoso and Fajardo 2018;

Demerens et al. 2013). The researchers concluded that managers are lured by the incentives and, therefore, use creative accounting to project attractive financial indicators. The researchers further indicated that executives with financial targets are likely to resort to creative accounting processes that allow them to manipulate the numbers to best serve their targets and incentives. It was concluded that when a company exceeds its earnings targets, and the managers’ incentives are linked to these targets, it is likely that the managers defer the reporting of excess profit to offset shortfalls in lean periods in order to attain persistent bonuses.

Nevertheless, a unanimous position was not achieved on the subject of negative accruals in case the target levels for receiving bonuses were not met. This study concluded that there was no evidence to conclude that cash and other incentives were the primary objectives behind creative accounting. It was indicated that job security was another potential reason that managers would defer reporting an additional profit (

Kamau et al. 2012). This way, managers could use the excess profit during a specified period in another period with a deficit.

3.1.3. Share Ownership Scheme

A share ownership scheme is a commonly used compensation mechanism, allowing managers, executives, and senior staff to become company owners. Shares are allotted under corporate remuneration or bonus agreements. Stock ownership schemes are used to reward company executives, reduce risks associated with agency problems, and provide better value to shareholders (

Mudel 2015). Several researchers consider rewards and bonuses to be the primary aspects that influence the use of active accounting (

Makhaiel and Sherer 2018). The studies’ overall idea is that executives are lured by the higher earning potential using stock ownership. This may prompt them to use creative accounting that eventually crosses over to the unlawful side. These assertions are in agreement with the authors of (

Holderness 2015), who indicated that executives participating in-stock programs might work towards lowering share price prior to the declaration of the stock and option date, since share prices are fixed on the chosen date.

These views are in line with those of (

Malik et al. 2011), who asserted that executives typically try to control stock accrual before the options reissuing date to obtain a higher number of shares.

Alit (

2017) expressed similar views and asserted that it is typical for managers to announce negative news prior to the option date so that share prices move in their favour. Others suggest that an increase in share price could be attributed to investor confidence about the similar direction of stockholders and the management’s wealth (

Eiler et al. 2015;

Rashid 2020a). The body of knowledge concerning this aspect indicates that managers try to influence earnings to maximise personal stock ownership. It was also suggested that management is unlikely to engage in behaviour that could malign the company’s long-term interests, since future executive compensation is tied with company performance (

Lari Dashtbayaz et al. 2019). The preceding discussion and arguments have not presented a comprehensive and convincing viewpoint concerning an income reduction for personal interests in company stock.

3.1.4. Income Smoothing

The literature review leads to the idea that income smoothing is the primary objective behind creative accounting, which can facilitate a reduction in earning fluctuations. Income smoothing refers to the tweaking of income levels to provide an indicator of typical business performance so that management objectives can be met (

Saleem 2019). Income smoothing is the practice of reducing extensive variability in reported income using a benchmark; the changes are facilitated using actual transactional factors or factors that are explicitly designated to achieve the smoothing objective. If these processes are continued for extensive periods, investors and other stakeholders will likely obtain a misrepresented picture of the business. Given that decision-makers use profit as a critical factor when making essential decisions, income reliability has unparalleled significance for ascertaining potential investments’ risk and reward (

Abed et al. 2020c).

However, aspects such as the high cost of securities and low capital cost provide benefits, meaning that businesses may engage in income smoothing (

Doan et al. 2020). Income smoothing can be performed by an authorised accountant who can manipulate the company’s revenue and expenditure to facilitate income smoothing (

Baik et al. 2020) using creative accounting. It was asserted that organisations engage in income smoothing when the company’s financial performance does not meet the expectations (

Trisanti 2016). The author indicates that future revenue accruals are recognised in the present fiscal period to enhance the numbers on the financial statement. Along the same lines, organisations defer recognising profits that are over and above the projected performance; these profits can be used in future periods to indicate better performance as required.

Moreover, big bath accounting is a commonly used technique that is correlated with income smoothing (

Ghorbani et al. 2020). This phenomenon comprises organisations reporting high levels of expenses and losses in the current year; this reporting highlights increased earnings in subsequent periods. Income smoothing is performed considering a long-term perspective because it allows for organisations to project themselves as consistent and stable. Banks also rely on income smoothing. Thus, banks with a stable income on paper offer relatively constant dividends compared to banks with varying earning levels (

Remenarić et al. 2018). These stable views provide a positive view to future lenders, who perceive a low risk. Stable profits are associated with a reduced cost of capital. Banks may indulge in income smoothing to placate individuals who use financial statements for decision-making (

Hammarbäck and Karlsson 2020).

Figure 2 shows the motivations behind creative accounting.

3.2. Creative Accounting Techniques

The fundamental aim of creative accounting is to identify the gaps in accounting standards and the prevailing laws, and exploit these to improve the financial indicators. Businesses can use creative accounting to project themselves more positively; however, this is successful when performed with minimal effect and a positive application (

Atabay and Dinç 2020). Nevertheless, it is typical for organisations to cross the line and step over to the other side, where such practices become questionable. Such practices not only violate the law but also have catastrophic implications. It can be concluded with certainty that creative accounting negatively impacts financial reporting. In a majority of cases, internal management is responsible for manipulating a business financials; employees perform questionable practices at the behest of the management. Financial information is misrepresented to project financials as the management deems best (

Vladu et al. 2017).

There is scope for manipulation where the accounting standards rely on estimates. Banks may perform creative accounting using different techniques that help management fulfil their objectives. Some actions include premature revenue recognition, where future revenue is incorrectly recognised in an earlier accounting period (

Cernusca et al. 2016). Future profits that have not been realised are reported in full in the present accounting period so that profits can be optimised. Along the same lines, managers defer the recognition of business expenses in the current accounting period. Capital expenditure recognition is deferred to future accounting periods (

Idris et al. 2012). The commonly used creative accounting methods are listed below.

3.2.1. Tangible Assets

The use of subjectivity in asset depreciation is an accounting domain where a large amount of creativity is used. Professional reasoning, IAS 36, requires that balance sheets are analysed and the corresponding asset depreciation is evaluated (

Abed et al. 2020a). If management understands that the residual value is less than what is accounted for, the assets are considered impaired. In these cases, the outcomes are influenced by recording depreciation on the balance sheet (

Akpanuko and Umoren 2018). However, if management has a positive view of the outcomes, asset depreciation is neither reported nor underreported to prevent diminished assets. The lease-back value is dependent on the reported depreciation and an asset’s year of sale (

Aureli et al. 2019). Hence, it is possible to use tangible assets and their depreciation for different creative accounting processes, such as handling impairment, amortisation schedule, tangible asset valuation, expense capitalisation after asset commissioning, and handling development expenses (

Anderson et al. 2014).

3.2.2. Goodwill

Underreporting purchased assets can be used to enhance goodwill. Goodwill is the added economic value that can facilitate additional future profits. It may be used to provide greater-than-expected asset profitability; average return on investment is one such indicator (

Carlin and Finch 2011). Goodwill is a distinct accounting concept that originates from mergers and acquisitions (

Hammarbäck and Karlsson 2020). If, during acquisition, an entity pays a higher amount than the fair value of the acquisition, goodwill is the difference between the consideration paid and the fair price. Goodwill is accounted as an asset in the financial statements of the acquiring entity. Previous research indicates that goodwill has the potential to add significant value to an entity. If goodwill is capitalised on after an acquisition, it typically raises concerns in the capital market (

Linsmeier and Wheeler 2021).

Nevertheless, it has been observed that executives target mergers or acquisitions to enhance personal income; therefore, goodwill is unable to add value to an entity (

Cavero Rubio et al. 2020). The principal agency framework suggests that the management is likely to be focused on short-term results due to the presence of the agency issue between company management and its stakeholders. Information asymmetry and inconsistency in objectives lead to short-sightedness in business. If mergers and acquisitions are performed without due diligence, there is a likelihood of conflict and higher risk for businesses; consequently, shareholders are affected. It is also crucial to ascertain the effects of goodwill on cash holdings. Goodwill adds risks to a business, causing financial roadblocks for business operations. High goodwill recognition is directly correlated with business integration risk. Entities with immense goodwill face higher non-systemic risks compared to entities with relatively less goodwill. Enormous goodwill leads to banks and other lenders imposing higher credit restrictions on such entities (

Carlin and Finch 2011).

3.2.3. Depreciation

It is essential to follow a specific depreciation scheme and adhere to accounting policies that are applicable to the entity. Using depreciation as a systematic tool for representing asset value during its useful economic life can affect profits. Outcomes may be changed by adhering to different depreciation schemes. The depreciation method depends on the accounting of expenditure for the asset. Expenditure can be changed by considering different values of the useful life of an asset. Depreciation amounts in the present and future accounting periods can be changed by considering different values of a useful economic life. Subtracting residual value leads to lesser depreciation, thereby enhancing the outcomes (

Repousis 2016). Reassessment techniques concerning tangible assets offer opportunities to change the depreciation value and period, facilitating manipulation in the balance sheet. The losses accumulated due to a reduction in equity can be offset using tangible asset reassessment. This technique allows businesses to survive downturns; however, these practices can have medium- to long-term implications for the company. Higher asset assessment leads to a higher depreciation base value, which causes higher depreciation expenses in the future, thereby affecting financial performance (

Palazzi et al. 2020).

To prevent such instances, entities may offset excess depreciation using the difference created during asset reassessment. In this way, depreciation expenses specific to the asset are accounted for, considering the fixed asset’s acquisition cost (

Lazo and Billings 2012). Hence, exercising different choices concerning the useful life of assets creates different depreciation expenses that affect the outcomes differently. Asset depreciation expenses in the present and future accounting periods are affected by a review of and change in an asset’s useful economic life (

Repousis 2016). In conclusion, it is stated that a comparison between the present (operating) financial performance of different entities should be made under similar depreciation periods; the other means of comparison is to not consider depreciation, where gross operating profits can be compared.

3.2.4. Inventories

Creative accounting can be amply used on inventory since there is immense subjectivity (

Lazo and Billings 2012). A deliberate error in reporting current inventory can lead to changes in assets; it is referred to as a result of “polishing”. This indicates that the difference (positive or negative) in inventory reporting affects the present and future accounting periods’ results. If finance costs are accounted for in production costs, financial outcomes differ because expenses are already accounted (

Lucchese and Di Carlo 2020). On the contrary, if the projected outcomes are adverse, the same method is used differently; interest expenses are accounted for in production costs (

Li et al. 2017).

3.2.5. Provisions for Liabilities

Income can be changed using provisions for the current and future years. If provisions are increased, net profit reduces; similarly, a reduction in provisions adds to net profit, thereby indicating a positive result (

Remenarić et al. 2018). Changing the provisioned resources is widely used to bring about the desired income change. Profits are decreased in the years in which provisions are increased, and vice versa. Pension obligations are future liabilities, and they are easy to manipulate because businesses need to account for future expenses (

Remenarić et al. 2018).

Executes may intentionally diminish provisions by considering uncertain recoveries as favourable debt recoveries. Increasing the net realisable value can facilitate a decrease in provisions. In contrast, contingent liabilities can be used to reduce profits by projecting future uncertainties concerning debt (

Suer 2014). Depreciation and useful life are other ways in which businesses practice creative accounting. Depreciation expense can be decreased if the useful life of an asset is considered optimistic. In this case, the value of an asset can be amortised over an extended period, thereby reducing annual depreciation expense and facilitating an increase in profit (

Susmus and Demirhan 2013).

3.2.6. Construction Contracts

Construction contracts can be accounted for differently using two prevalent methods. For a fulfilled construction contract, accounting is performed at contract fulfilment. Tangible results are staggered throughout the contract fulfilment using a percentage-based technique. Switching accounting methods can affect profit and loss (

Kotlarz 2018). Some construction contract cases used for accounting include the in-progress construction of the office premises to be used by the organisation; a contract-based building under construction; fixed assets that are deemed saleable; vehicles that are deemed saleable during ongoing business operation, and other cases (

Szymański 2017).

From the perspective of a potential future investor, there is a chance that the project will be scrapped. Investors can protect themselves against unfavourable financial situations by raising capital for the construction contract; halting investments is one unfavourable financial situation. The use of appropriate funds is typically correlated with future decisions concerning the use of internal or external capital corresponding to a specific unit. The appropriate use of capital depends on the ability of, and decisions made by, the leadership; the situation should be objectively and analytically assessed to ensure that the investment that is required for completion is available (

Iatridis and Alexakis 2012).

Figure 3 displays the creative accounting techniques.

3.3. Effects of Creative Accounting

Creative accounting has been seriously considered in recent years due to numerous accounting scandals in large corporations (e.g., WorldCom and Enron). Developed and developing nations have had their banking sector affected due to accounting scandals (e.g., BCCI, Barings, Allied Irish Bank, Baninter, and Imarbank) (

Amat et al. 1999). Considering the significant effect such frauds have on the national and global economy, businesses, authorities, and governments are more watchful of creative accounting (

Iqbal et al. 2015). The accounting policy is not always comprehensive; loopholes exist and pave the way for legal creative accounting (

Gupta and Kumar 2020). Simultaneously, there is always the illegal side of creative accounting, which comprises manipulation, fraud, and misinformation. Apart from the legal provisions, the effective application of generally accepted accounting principles, private auditors’ autonomy, government supervision, ethics, and disclosure are considered to be significant professional and administrative provisions for handling creative accounting (

Suer 2014).

A few individuals or groups benefit from creative accounting, at the expense of a relatively large number of people. The negative aspects of the accounting profession, caused by relatively compromising individuals, are called creative accounting (

Sanusi and Izedonmi 2014); this comprises the introduction of complications and different ways of treating assets, liabilities, income, expenditure, and other financial aspects to influence readers to form the desired viewpoint (

Trisanti 2016). The intended use of financial reports is to present a fair and unbiased view of business operations to interested parties and allow them to make informed and objective decisions. However, the International Accounting Standards (IAS), Statement of Accounting Standards (SAS), CAMA, Banks and Other Financial Institutions Act (BOFIA), and the Iraqi authorities provide guidelines and regulations for accounting processes that often leave gaps, which are exploited by accountants.

3.4. Determinants of Creative Accounting

This section discusses the origin of earnings frameworks and the reasons for resorting to creative accounting. Subsequently, there is a discussion concerning the existing studies concerning this domain; the emphasis is on recent studies highlighting the motivations behind creative accounting in developed economies and contrasting them with non-existent issues in developing markets (

Tassadaq and Malik 2015). The legal status of creative accounting is disputed; though not entirely illegal, some aspects have ethical concerns for businesses and accountants. Creative accounting seeks to benefit a small set of individuals at the expense of others. When providing a definitive conclusion concerning the ethics of creative accounting, it is vital to consider philosophical concepts to determine the nature of actions that were not utilised in the previous literature (

Al Momamani and Obeidat 2013;

Martin et al. 2019;

Mudel 2015;

Gupta and Kumar 2020).

3.4.1. Ethical Issues

Financial reporting is significantly impacted by the many ethical issues (EI) stemming from the use of creative accounting. The agency issue and related challenges mandate the need for financial disclosure and reporting. The management and shareholders of an entity are a classic example of the principal–agent relationship (

Brass Island 2011). Vital aspects of this relationship include information asymmetry due to evasive action, conflicts of interest, concealing information, aspects of moral hazard, and adverse selection. The authors of (

Hentati-Klila et al. 2017) state that creative accounting results from conflicts of interest between different stakeholder groups; market regulations consider this a critical concern. Therefore, authorities enforce processes and provisions that seek to address such information issues, protect the public interest, and restore market confidence. Creative accounting is responsible for many global financial scandals. It is clear that organisations do not properly follow the rules and regulations (

Butala and Khan 2011).

There is extensive discussion in the literature concerning the precise definition of creative accounting and its ethical aspects. The present study assesses the challenges pertaining to creative accounting from a theoretical and empirical standpoint, with the objective of ascertaining what makes creative accounting unethical (

Akpanuko and Umoren 2018). Ethics frameworks typically attempt to mention or identify the aspects that concern individuals and society (

Tassadaq and Malik 2015). These frameworks review how humans are expected to behave in practical scenarios to ensure that all actions are considered acceptable, i.e., favourable for the individual and the others. A typical guiding rule and the crux of all ethics frameworks is that actions should be fair and attempt to do good for society, considering the fundamental duty of caring for others (

Engelseth and Kritchanchai 2018).

Hence, an action is considered correct if it is in line with moral laws, obligations, or duties (

Brass Island 2011). Human action should be just or right, as determined using ‘reason’; moreover, these actions need to be performed as duties, which provides the incentive aspect (

Tassadaq and Malik 2015). Aristoteles considers an individual’s character rather than judging every action on the basis of the ends or the fundamental principles (

De Jesus et al. 2020). They assert that individuals with virtue are capable of undertaking moral decisions. Hence, such decisions require a virtuous personality, which must be built through a ‘good upbringing and nurtured over time from childhood’. Hence, ethics is not about making morally right decisions or adhering to laws or traditions; instead, ethics comprises aspects of character that enhance human hospitality (

Rozidi et al. 2015).

3.4.2. Disclosure Quality

Disclosure quality (DQ) does not have a global, qualitative or quantitative definition. Nevertheless, researchers such as (

Nobanee and Ellili 2017) note that disclosure quality concerns the information’s relevence to numerous external parties; moreover, it should be available for audit. Disclosure quality is based on the utility of the information to interested users regarding informed decision-making (

De Luca et al. 2020). In contrast, the authors of (

Yao et al. 2020) discussed information audits to certify reliability and ensure proper accountability for decision-makers. The comprehensiveness of corporate social responsibility data regards the level to which individuals can use the provided information to understand and appreciate the social activities undertaken by business managers and understand their perspective on those actions (

Yekini and Jallow 2012).

Considering the non-existence of a unifying theoretical foundation, the existing literature approaches non-financial reporting causes using economic and socio-political theories (

Maama et al. 2020). In this context, (

Roszkowska-Menkes 2018) describes corporate social responsibility as a complex, multifaceted process that is dependent on complementary aspects; hence, it is improbable to use one theoretical construct to define this concept. Previous works concerning environmental and social disclosure have extensively used the Noe-institutional theory. The underlying presupposition is that organisations disclose information due to the pressure exerted by the institutional setup.

3.4.3. Internal Control

It is presupposed that higher internal control (IC) addresses issues related to governance and financial reporting quality. Management may address agency costs by staying vigilant at the lower level. An internal control process could be an effective regulatory system (

Brauweiler et al. 2019). High-quality financial reporting is dependent on creating a robust, effective, and high-quality internal control mechanism. Recent research indicates that poor internal control may lead to higher material errors and inaccurate financial disclosure, which is indicative of the use of creative accounting (

Richman and Richman 2012). Numerous financial scandals led to the passing of the Sarbanes Oxley act. Under this new law, public corporations were mandated to focus on comprehensive and effective internal control schemes. The passage of this Act provides an insight into the weak state of internal control that was prevalent at the time. Corporate governance comprises the organisational processes used to formulate, implement and use internal controls (

Alzeban 2020).

Several works have focused on determining the aspects and effects of weak internal control. Studies have revealed that there is a correlation between specified weaknesses, business aspects such as complexity, organisational change, investment, and profitability (

Buallay 2018). Inadequate internal control is considered a shortcoming, and several studies use such data to assess how internal control is correlated with financial reporting quality (

Wood and Small 2019). Preceding assessments indicated that inadequate internal control substantially affects financial reporting quality. Thus, higher unforeseen accruals correlate with weak internal control; the authors attribute management weakness to gaps in accounting (

Barandak and Mohammadi 2020).

Furthermore, it is established that organisations that disclose information about internal control highlight significant weaknesses regarding how the size of the audit firm influences the quality of audit reports (

Foster et al. 2013). The researchers determined that large auditing firms dedicate more time to internal control mechanisms than smaller firms. Large renowned auditing firms typically have structured internal control over financial reporting (ICFR) and, therefore, are restricted to lesser changes concerning reporting quality (

Lim et al. 2017). Firms disclosing audit and management data earn lesser gross revenue compared to firms disclosing only management reports (

Foster et al. 2013). However, the disclosure of audit reports offers a comprehensive and accurate overview of the business, for use by analysts and other interested parties.

3.4.4. Ownership Structure

The ownership aspect is mentioned in the literature in terms of ownership structure (OS). Two aspects comprise an entity’s ownership. First, the level of ownership concentration is a significant factor, as banks have a different ownership structure due to there being relatively high or less dispersion. The nature of ownership is the second factor; considering a similar degree of concentration, there might be a difference at the bank level if the government is the majority stakeholder. Along the same lines, stock-based firms with dispersed ownership and mutual firms are fundamentally different (

Mudel 2015).

The Iraqi banking sector has different ownership structures, namely, government-owned banks (GOBs), privately owned stock banks (POBs), and mutual banks (MBs). The literature makes extensive mention of the correlation between financial reporting quality and the entity’s ownership structure (

Brauweiler et al. 2019). A firm’s ownership structure significantly determined business value and provided information about its corporate governance (

Nagata and Nguyen 2017). Research concerning the association between financial reporting quality and ownership has not produced sharp results. Financial disclosure and ownership structure have a negative association (

Arthur et al. 2019). In contrast, (

Yasser et al. 2017) crunched the data for the top 200 public non-financial firms. The researchers determined that ownership concentration and financial reporting quality are directly correlated. Moreover, there are better avenues for technology transfer, capital support, and experience (

Alzoubi 2016;

Mousavi Shiri et al. 2018).

The research indicates that family businesses with controlling stakeholders have a higher probability of being run by the stakeholders themselves (as compared to considering external hiring) (

Giacosa et al. 2017). Controlling stockholders use the ownership structure to administer member entities using a minimal portion of cash flow rights (

Sahasranamam et al. 2020). Recent research provides enough evidence showing the misuse of insider information by controlling stockholders; these individuals exploit information to exercise greater control and obtain personal benefit at the expense of the minority holders.

Figure 4 presents the structure of creative accounting determinants.

4. Financial Reporting

The accounting that is conducted and maintained by a business is the foundation of financial reporting. It comprises identifying, gathering, and assessing all the business’s financial transactions (

Tri Wahyuni et al. 2020). All transactions performed by the business are processed using the prevalent accounting standards and rules (

Bhasin 2015). Accounting standards are the foundation of the accounting system, and these standards define the best practices in accounting and reporting (

Briloff 1972). If accounting information comprises inconsistent measurements, untrustworthy estimation, or fabricated transactions, the financial statements are bound to be wrong, incomplete, and misleading. There have been several reports of people being misled for extended periods by financial reports that failed to report correct, usable, and practical information about the business (

Mamo 2014).

The desirable aspects of financial reporting result from the joint efforts of accounting practitioners and conventions (

Korutaro Nkundabanyanga et al. 2013). The financial accounting standards board (FASB) and the international standards board (IASB) work together to address inconsistencies and disagreements corresponding to their respective frameworks. It is understood that this joint effort and a collective framework will provide high-quality financial reporting standards and improve reporting quality and utility (

Bini et al. 2015). Financial reporting is useful if the information presented by the reports helps in objective and informed decision-making. Financial reporting may be considered useful if it aligns with customer expectations or helps correct analyst positionings (

Qian et al. 2015).

The audit domain requires materiality; therefore, the cost associated with producing quality financial information for inclusion in reports is compared with the advantages of its inclusion in reporting (

Amin and Mohamed 2016). Relevance comprises several secondary aspects that have evolved over time. These aspects include representational authenticity, identifying and accounting transactions as-is, and indicating their true nature (

Feiler and Teece 2014). The notion of neutrality is associated with accurate and uninfluenced financial reporting, conducted without any intention of affecting the outcomes (

Rose et al. 2017). Completeness refers to the full disclosure of material information as opposed to partial representation (

Yasser et al. 2016). Financial reporting missing one or more of the abovementioned aspects is considered creative accounting (

Akenbor and Ibanichuka 2012). Along these lines, it can be asserted that accounting conventions have led practitioners to formulate accounting standards. The standards set during these conventions facilitate the identification of financial reports where businesses employ creative accounting or earning management methods (

Kardan et al. 2016).

4.1. Financial Reporting Quality

Financial reporting quality (FRQ) is considered a precise way of representing information pertaining to business processes (

Shahzad et al. 2019). It is associated with projected cash flows; the objective is to appraise company shareholders regarding their business operations. Financial reporting quality is the degree of fairness and authenticity of business information and organisation performance (

Lim et al. 2017). These definitions suggest that financial statements are considered ‘high-quality’ when they convey precise information concerning the financial performance, economic position, business operations, cash flows, and other business metrics required by shareholders and other users. Financial reporting quality is the authenticity of the information presented to the users through the financial reports (

Hadiyanto et al. 2018).

The value relevance model uses accounting indicators and stock market responses to determine the quality of financial statements (

Rashid 2020a). The market value of a business is indicated by stock price; at the same time, a business’s value is indicated by accounting figures determined using accounting processes (

Kardan et al. 2016). The model has good utility; however, its downsides include accurately predicting stock price and market value. The technique used to operationalise the qualitative aspects of the report may be referred to as the International Accounting Standard Board (IASB) qualitative framework. Thus, enhancements and fundamental characteristics are the two aspects of qualitative characteristics (

Hadiyanto et al. 2018).

Relevance and faithful representation are the two fundamental characteristics that are vital to ascertain financial reporting quality. Nevertheless, several other characteristics, such as comparability and understandability, are used to augment the fundamental characteristics needed to prepare high-quality financial statements. These statements are considered relevant and useful when they present information that allows the users to accurately assess and understand past and present events and make informed economic decisions (

Rashid 2020a). Relevance characteristics relate to those that influence the decision-making ability of the users.

The fundamental of faithful representation is to document economic activity without any manipulation. Comparability is an enhancing aspect whereby similar or alike events can be reflected using similar or identical accounting processes; different economic events should be reflected using different figures and other indicators to clearly and objectively convey the differences for their straightforward comparability and interpretability (

Rashid 2020a). Users may want to compare financial statements from different periods or statements from different companies for one or more periods; comparability is the characteristic that facilitates users to achieve this objective. Financial statements are expected to be comprehensible; a high-quality financial report is easily understandable and allows for sufficient information dissemination. Additionally, The IASB qualitative characteristics framework is used to select the aspects of financial reporting quality that are used in the present study (

Salehi et al. 2018).

Therefore, financial reporting quality is significant because high quality is associated with benefits to the an organisation’s stakeholders; low-quality financial reporting is expected to adversely affect stakeholders. Managers of public sector organisations are responsible for making economic decisions concerning the public money and assets entrusted to them by domestic and foreign investors, taxpayers, donors, and other parties that expect objective decision-making. Businesses convey financial information to their stakeholders using financial reports, which makes accurate reporting vital (

Cernusca et al. 2016). The accurate reporting of accounts and finances by government systems and disclosure processes is considered important (

Dabbicco 2015). Furthermore, reporting is the official process used by organisations to communicate financial and operational information to their stakeholders (

Yasser et al. 2016).

4.1.1. Relevance

The Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB) Framework attributes a “predictive and confirmatory role” to relevance; this indicates that information should be relevant for decision-makers and other users. Additionally, information is relevant when it helps users make economic decisions (

Akpanuko and Umoren 2018). It is asserted that the materiality and nature of information affects its relevance. Moreover, information is considered material if its misrepresentation or omission can affect the decisions of users who rely on the financial reports (

Saleem et al. 2020). The definition specified by the AASB Framework is comparable to other definitions that were suggested in the review period (

Kewo 2017). Authors have used several attributes to characterise relevance. Usefulness and materiality are two critical attributes used to define relevance from the 1960s to the 2000s. Usefulness was subsequently considered decision-usefulness, thereby integrating the concept of timeliness.

The predictive value is the most significant aspect concerning relevance because it affects decision usefulness and allows for the measurement of predictive value using three constructs. The first construct assesses the degree to which annual reports are indicative of future business scenarios. Forward-looking financial statements project the management’s vision concerning the future of the organisation. The management has access to information that helps it predict future business conditions; stockholders and other individuals are typically not aware of this information. Therefore, investors and other capital providers find such information useful if present in the annual report. The second construct concerns the degree of information disclosure concerning business risks and opportunities (

Kruglyak and Shvyreva 2018). Non-financial information complements financial information in terms of its predictive value. Information concerning business risks and opportunities is useful to understand potential future business scenarios (

Cheung et al. 2010).

The third construct assesses how the company uses the fair value concept. The existing literature typically indicates that fair value and historical cost are used to ascertain the predictive significance of financial reporting information (

Cohen and Karatzimas 2017). Researchers typically claim that fair value accounting is better than the historical cost technique because the present asset value is used rather than its purchase price (

Cheung et al. 2010). Furthermore, the IASB and FASB are presently contemplating revising the standards that facilitate the better use of fair value accounting to enhance the significance of financial reporting. Fair value is understood as a crucial technique to enhance relevance (

Kruglyak and Shvyreva 2018).

Confirmatory value complements predictive value to enhance the relevance of financial reporting. Information is considered to have a confirmatory value if its previous assessments can be used to validate or change present (or past) expectations (

Saleem et al. 2020). The data contained in the annual report inform the users about past financial events or transactions, and help to confirm or modify their expectations (

Elmashharawi and Sabour 2020). The Management, Discussion and Analysis (MD&A) portion of the annual report, along with other financial statements, may be studied to obtain information concerning the information’s confirmatory value. These sections typically comprise information with confirmatory value (

Elsiddig Ahmed 2020).

4.1.2. Faithful Representation

Faithful representation is the second fundamental qualitative aspect. Annual reports should be comprehensive, error-free, and neutral so that the information contained within is represented faithfully. Accounting standards specify that the economic processes characterised in the annual report comprise economic resources, transactions, obligations, events with financial implications, and the conditions that modify them. The direct measurement of faithful representing, conducted by evaluating only the annual report, is challenging because it is vital to obtain information concerning real-world economic phenomena to ensure a faithful representation (

Muraina and Dandago 2020).

However, (

Cernusca et al. 2016) suggest that the estimates and presuppositions concerning economic aspects that are highly indicative of the true economic situation are indicative of faithful representation. Hence, this study emphasises the elements of an annual report that increase the likelihood of faithful representation. These elements do not need to refer to IFRS or US GAAP; however, they are still an indirect means of faithful financial representation, as per particular accounting rules. The first proxy concerns the concept of ‘free of bias’. It is unfeasible for an annual report to be utterly bias-free, since the phenomena stated in such reports are typically determined under uncertain conditions. The annual report comprises several presuppositions and estimates. Even though a bias-free scenario is infeasible, there needs to be a reasonable accuracy level concerning financial reporting information to allow for meaningful decisions.

Neutrality concerns the preparer’s intent; whether they attempt to present events objectively or emphasise only the events that convey positivity and ignore the negative aspects. Another construct used to determine faithful representation is the report of an unqualified auditor. Numerous researchers have studied the effects of audits and audit reports on the economic value of the organisation (

Atabay and Dinç 2020). These authors determined that the audit report provides added value for financial reporting by facilitating assurance regarding annual reports; the users are assured to some degree that faithful representation has been adhered to. An unqualified audit report is critical to ensure reliable and faithful financial information reporting (

Bean and Irvine 2015).

Lastly, a significant aspect of faithful representation in annual reports is the corporate governance statements. Corporate governance defines the techniques that limited-liability business organisations use to control and direct the business. Numerous researchers have assessed the correlation between financial reporting quality and corporate governance, internal control, fraud, and earnings misrepresentation. They found that financial reporting quality deteriorates due to poor internal control and governance systems (

Bimo et al. 2019). It is understood that corporate-governance-specific information provides value to capital providers. Corporate-governance-specific information enhances the likelihood of faithful representation (

Tassadaq and Malik 2015).

4.1.3. Understandability

The Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB) defines understandability as a fundamental aspect concerning the information presented in financial reports. The information should be comfortable and straightforward to understand (

Habib et al. 2019). It is assumed that users possess adequate knowledge concerning economic activities and other business aspects, such as accounting. Furthermore, users are also expected to be willing to evaluate this information with diligence (

Bini et al. 2015). Previously, understandability was considered as “sufficient wording in a ‘narrative’ or ‘vertical’ form of financial statements to make themselves explanatory” (

Cheung et al. 2010). Understandability has since been associated with communication. Two fundamental developments have been emphasised: what or who was the focus specific to building understandability, and whether technical or non-technical terms should be used to report financial information.

Moreover, disclosure specific to the comments specified in the balance sheet and income statement might be useful for providing detailed information concerning earnings (

Cheung et al. 2010). Narrative forms are specifically useful for enhancing understandability. Furthermore, the use of graphics and tabular data is expected to enhance understandability, since relationships are concisely clarified (

Rashid 2020b). Additionally, if the individual preparing the annual report uses words and frames with easily comprehensible sentences, the reader will likely obtain a better understanding of the content (

Kardan et al. 2016). If it is unfeasible to work without technical terms, the inclusion of a glossary section is suggested, providing additional information to help understand complex terms (

Cheung et al. 2010).

4.1.4. Comparability

Comparability requires that matching situations are indicated using the same accounting facts and figures (

Cheung et al. 2010). In contrast, different situations are expected to have different accounting methods, so that the differences are understandable and easily interpretable. Hence, businesses operations in comparable scenarios select similar accounting techniques (

Kardan et al. 2016). Dissimilarities between the figures stated in annual reports that do not occur due to performance are expected to be removed (

Rashid 2020a). Uniformity/standardisation and consistency are two terms that became popular in the 2000s, which are used to explain comparability. Consistency requires that all periods use the same techniques or explicitly report the variations (

Carlin and Finch 2011).

It is suggested that companies emphasise consistency to achieve comparability. Consistency can be optimalized by indicating the ability to handle uncertainty and change (

Kardan et al. 2016). Businesses revise estimates, accounting procedures, and judgements in response to the latest rules, regulations, or information. For instance, it may be necessary to update estimates concerning an asset after its expected lifetime is updated. CRegarding consistency, it is vital that businesses provide information about the effects of such changes on previous results. It is crucial to obtain comparable earnings estimates in order to precisely evaluate business performance. If a business modifies its accounting policies, judgements, or estimates, it may change previous years’ earnings figures to visually assess these changes.

Moreover, since consistency requires that accounting principles are kept the same, the revised figures should be similar to the previous years’ figures. When an organisation offers a comparison of the financial results over several years, even without any change in judgements, estimates, or accounting procedures, financial information comparability is enhanced. Comparability not only considers the ongoing use of accounting procedures by one firm; it also considers the comparability of financial reports across firms. Thus, when evaluating the comparability of the annual reports of different organisations, it is crucial to emphasise the annual report structure, accounting policies, transaction description, and other developments (

Kardan et al. 2016).

In conclusion, the main intention of financial reports is to provide institutions with brief and clear data on the institution’s financial status. These reports will enable users of those reports to make decisions on the economic status of the institution (

Zheng and Chen 2017). The characteristic of qualitative reporting is considered an essential aspect when attepting fulfil the required status of financial reporting. In contrast, this criterion contributes to extending the applicability of the financial reports. The relevant criteria when high-quality financial reporting are highlighted in this section, and

Figure 5 displays the main principles of qualitative characteristics in the financial reporting matrix.

5. Discussion

This section presents a critical review and analysis of the creative accounting review studies. The literature survey listed the necessary information about these studies, as well as the strength and weaknesses of each study. Moreover, it explored the (techniques/method/approach) followed by these studies in order to define the subproblems that are not covered by these studies. Most studies were limited by the research environment of the companies, such as an emerging capital market in a specific country. Therefore, the findings reported in this study might not be generalisable to other firms in other countries with different economic and business settings (

Gupta and Kumar 2020;

Abed et al. 2020b;

Mudel 2015).

Moreover, this study did not consider the corporate culture environment and moral awareness (

Abed et al. 2022a). Reference (

Bimo et al. 2019) did not address the accounting framework’s effect on the financial reporting system. This will ultimately lead to less erosion of shareholder value in particular, and economic resources in general (

Shehadeh et al. 2022). Moreover, this study was limited by corporate enterprises in the private sector only. Another study (

Abed et al. 2022b) needed the audit committee, additional characteristics such as the number of audit meetings, the proportion of audit committee members with accounting or financial expertise, and their previous experience activities, which could be included to detect their effects on international standard practices (

Haddad 2016). However, the researchers did not recognize that other internal factors, such as ownership structure, ethical orientation and the qualification of management staff, could also influence the quality of financial statements. Moreover, no transparent approach was followed in this research (

Haddad et al. 2017).

Another study (

Goel 2014) was limited as it examined auditors’ perception of earnings management and excluded the accountants’ perspective. Archival studies in this setting are undoubtedly valuable and informative. However, there are some limitations, such as the impact of an increase in the accounting regulations loopholes and creative accounting, and the cost of techniques that define creative accounting; often, these prove to be extremely expensive (

Bhasin 2015;

Al Momamani and Obeidat 2013). Unintentional and intentional errors occur in accounting companies (

De Jesus et al. 2020), such as credit rating agencies who could not predict fraud (

Mulford and Comiskey 2012). This study concluded that comparing firms based on the presence or absence of creative accounting is likely insufficient to determine the effect; therefore, it is important to consider complementary investments in internal control (

Martin et al. 2019).

Furthermore, in Reference (

Fraij et al. 2021), the researchers did not recognise the fact that other internal factors, such as ownership structure, ethical orientation and the qualification of management staff, could also influence the quality of financial statements. Moreover, no clear approach was followed in this research (

Krishnan et al. 2020). From the limitations of the above studies, according to a review of the literature on creative accounting, the issues in measuring creative accounting and assessing its impact need immediate attention. This issue has received much attention from researchers in both the UK and the USA (

Mulford and Comiskey 2012). However, it is still seriously underaddressed in developing countries (

Iqbal et al. 2015;

Yasser et al. 2017). Moreover, attempts to develop frameworks for the measurement of creative accounting in developing countries, as opposed to the frameworks used in more developed economies, need investigation (

Yasser et al. 2017). Finally, future research should consider some factors that impact financial reporting quality, such as ethical issues, disclosure quality, internal control and ownership structure (

Martin et al. 2019). What constitutes a liability in accounting is problematic, as evidenced by inconsistent definitions across IFRS standards (

Qian et al. 2015;

Cheung et al. 2010).

6. Conclusions

Creative accounting is still a large challenge in financial accounting. This study aimed to provide a comprehensive analysis of the existing literature to offer an advantage, and face the challenges, in creative accounting and financial reporting. Thus, several criteria were followed when selecting the reviewed databases, such as the reliability and wide representativeness of a collection of references. The growing progress in this field allowed for the timeliness of this study. The review highlighted the problems and motivations concerning creative accounting practices. Thereafter, the present review identified that financial reporting was highly associated with creative accounting practices over the last decade, whereas most fraud was identified in small businesses. Accordingly, the stockholder’s and investors’ confidence in financial reporting quality dramatically decreased. Thus, the academic research context shows higher significance in investigating the contemporary situation in comparison to the previous literature, which took place after the damage had occurred. In conclusion, this paper is designed to provide a first, broad overview for academic researchers and provide a practical financial context for determining creative accounting practice and its impacts on fraud financial reporting over the period between 2015 and 2020. Further, it addressed the essential constructs on which reform in the financial sector can be based. This will also allow academic research to prepare to objectively detect and inform creative accounting practices.