Abstract

Life insurers, whose contractual liabilities include providing minimum guaranteed interest rates to policyholders, are significantly affected by persistently low interest rates. Hence, this study reviews the literature on the prolonged low interest rate environment and its impact on the life insurance industry, incorporating multiple perspectives and practices in different countries. The effect of low interest rates on life insurance products depends on the sensitivity of the interest rate of each product type and the level of minimum interest rate guarantee. In addition, their impacts on the valuation of life insurance companies depend on shifts in the valuation interest rate, which is used to discount the present value of future benefits, as well as the financial and solvency issues faced by insurers. Overall, the literature suggests that insurers need both short- and long-term solutions to respond to a prolonged low interest rate environment.

1. Introduction

During the past few decades, interest rates have dropped in various markets worldwide (Del Negro et al. 2019; Hartley et al. 2016; Holsboer 2000; Reyna et al. 2022). For instance, in 2011, the long-term benchmark yield of a ten-year government bond declined for the first time to 3.92%, below the 4% technical interest rate provision required by European regulators (Kablau and Weiß 2014). Berdin and Gründl (2015) described these low interest rates as, “a threat to the stability of the life insurance industry” (p. 385). The life insurance business is susceptible to changes in long-term rates due to its contractual obligations to policyholders (Holsboer 2000).

Today, most people are covered by life insurance. Life insurers function as financial intermediaries, or “carriers.” They buy financial instruments, such as government and corporate bonds, and bundle them with life and annuity benefits to offer to customers (Love and Miller 2013). The successful operation of life insurance assumes that insurers balance consumers’ needs for security against the interest rate sensitivity of the offered products. However, the life insurance industry operates in rising and falling interest rate environments, which impact profitability.

Eling and Holder (2013a) emphasized that, “life insurance is an interest-sensitive business” (p. 354). This is because the values of both assets and liabilities of life insurers change as the interest rate changes (Berends et al. 2013). Berends et al. (2013) asserted that liability duration may be extended in a low interest rate environment, as policyholders are unlikely to surrender their policies. We anticipate that policyholders’ surrender behavior significantly impacts life insurance duration. This phenomenon accelerates the negative duration gap because the increased duration of liabilities is much longer than the duration of held assets (Antolin et al. 2011). The longer the duration of liabilities, the higher the sensitivity to interest rate changes. Therefore, low interest rates are more likely to significantly impact life insurers due to the high sensitivity of liabilities to interest rate variations.

Over the past few decades, low interest rates have become a global issue, especially when long-term bond yields drop to historical lows (Holsboer 2000). The present literature review provides new insights into the case of globally persistent low interest rates. The main objective of this study is to explore extant research insights regarding the impact of prolonged low interest rates on the life insurance business. This study addresses the following research questions:

- What has been the trend in global interest rates since 1990?

- How are life insurance products affected by a low interest rate?

- How do low interest rates change insurer valuation and solvency?

- How can financial management strategies respond to a prolonged low interest rate environment?

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 briefly reviews the study’s conceptual background and the historical financial crises caused by low interest rates. Section 3 outlines the study’s methodology. Section 4 presents the study’s results on how low interest rates impact life insurance products and valuations of life insurers, proposing short- and long-term solutions for insurers to respond to low interest rate environments. Finally, Section 5 discusses the study’s limitations, interpretations, and implications for future research.

Our study fills the gap in prior literature through two main perspectives. First, we summarize past research on the low interest rate environment in the life insurance context. We also identify causes and effects for life insurers. Our main managerial contribution is to support life insurance companies’ strategies with a course of action to deal with a low interest rate environment. Second, we address various perspectives on the prolonged low interest rate phenomena by synthesizing them into a knowledge base (Whittemore and Knafl 2005). Our extant literature focuses exclusively on either the product or valuation perspective. The present review is the first to aggregate insights from these two standpoints to collectively define challenges faced by life insurers during a protracted low interest rate environment.

2. Conceptual Background

To respond to a prolonged low interest rate environment, life insurers need to consider the interest rate’s impacts on life insurance products’ profitability, linking it to insurers’ investment and financial results. Reyna et al. (2022) mentioned two primary profit sources for life insurance companies, one being a life insurance operation that guarantees premium income minus expenses. Brown and Galitz (1982) called this source “underwriting profit” (p. 290). Another source of profit relates to investments in technical reserves. These two sources have a more noticeable impact in a low interest rate environment due to insurers’ challenges in pricing and valuation. Life insurers struggle when the available margin from the investment return over the guaranteed minimum return is insufficient to fund future life insurance obligations (Kablau and Wedow 2012).

Options such as a minimum guaranteed interest rate on the saving component and policyholder participation in the profit-sharing scheme of life insurers are often embedded in life insurance policies. These crucial guarantees require appropriate valuation and hedging to keep the insurer solvent (Schmeiser and Wagner 2015). However, minimum guaranteed interest rates are usually set below market interest rates at first launch, with an out-of-the-money option (Berends et al. 2013). This strategy emphasizes that an adequate asset and liability management (ALM) framework may mitigate interest rate risk in a prolonged low interest rate environment, supporting new product development (Focarelli 2015; Holsboer 2000; Paetzmann 2011). This ALM framework is widely adopted by life insurers as a risk management tool (Holsboer 2000) and was previously applied by the banking industry. Banks have successfully used the duration matching approach of ALM to minimize the interest rate risks (Romanyuk 2010). Borri et al. (2018) applied canonical correlation analysis to study the relationship between assets and liabilities of European life insurers during a “low-rate” period. The result of high exposure to ALM risk from less dependency between assets and liabilities supplements the usefulness of the ALM tool in both industries.

Interest rates have varied significantly over the past few decades. In the early 1990s, the United States (US) began recovering from a recession, with the long-term interest rate hitting 6%, followed by a decrease to 4.7% by the end of 1998 (Holsboer 2000). From the end of 2007 to mid-2009, the Great Recession in the US caused an economic downturn, a more than 10% decline in GDP, a 25% unemployment rate, a bursting of the housing bubble burst, a correction of the housing market, and a subprime mortgage crisis. The global financial crisis pushed interest rates close to zero to stimulate spending and investment (LePan 2019). Europe’s sovereign debt crisis followed, causing rating agencies to downgrade various Eurozone countries’ debts. From 2009 to 2010, two European insurers, Victoria Life and Delta Lloyd Groep, stopped their new business underwriting (i.e., new policy issues) due to the low interest rate environment (Paetzmann 2011).

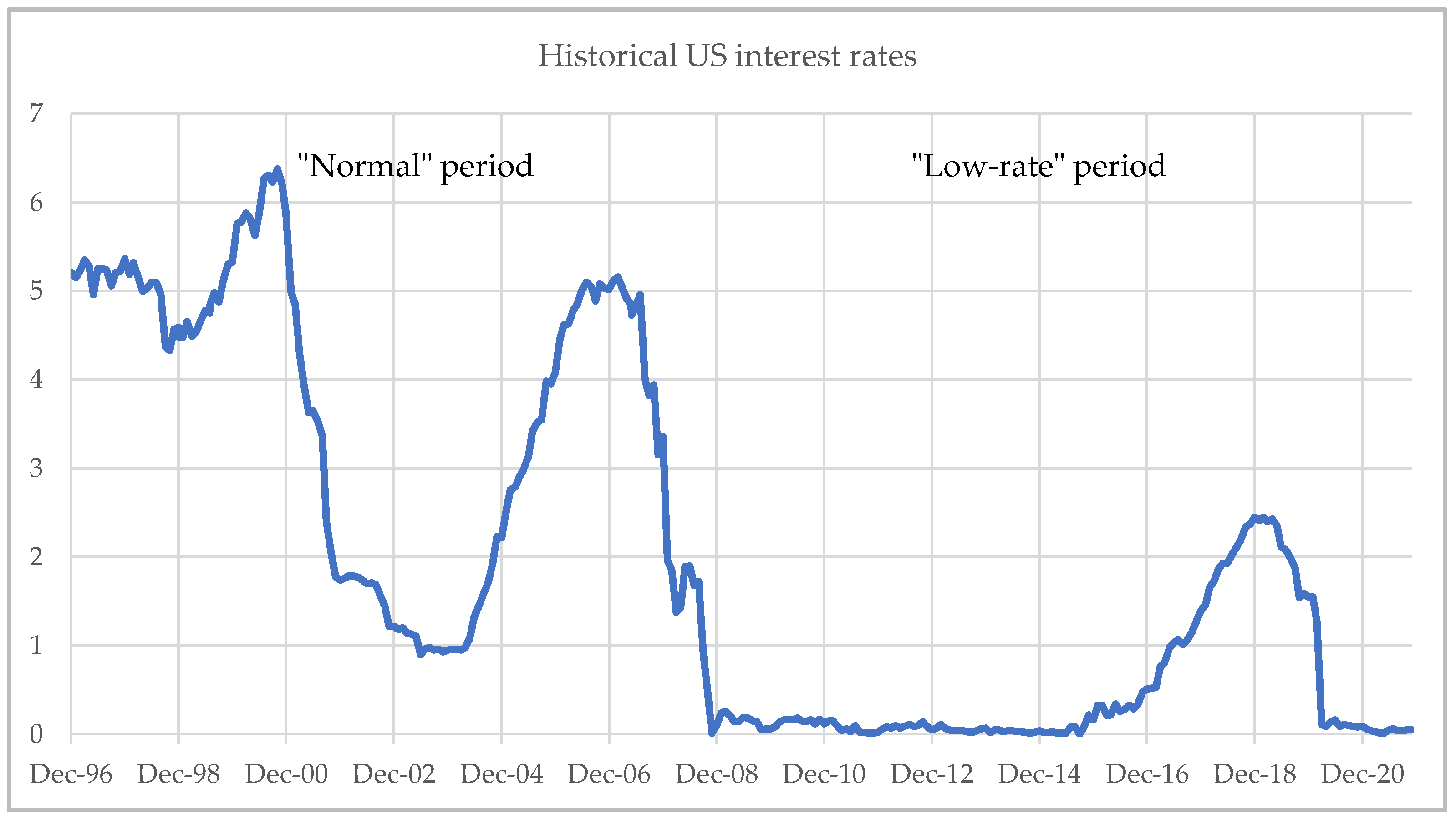

Hartley et al. (2016) classified interest rates into “normal” and “low-rate” periods (Figure 1). Between 2002 and mid-June 2007—a “normal” period—small changes in interest rates did not affect insurers’ stock prices in the US and the United Kingdom (UK). Interest rates were within their historical norm. However, after the 2007–2008 financial crisis, the long-term interest rate drastically decreased, leveled off at a historically low level, and has stayed at that low rate since then (Hartley et al. 2016). Reyna et al. (2022) emphasized that insurers must implement specific actions to recover their profit margins after a period of persistently low interest rates.

Figure 1.

Historical US Interest Rates (adapted from Trading Economics 2022).

In mid-2016, most Asian countries, including Taiwan and Hong Kong, recorded historically low zero-coupon government bond yields. By contrast, Japanese and European government bond yields became negative for almost all tenors (Nieder 2016). Between 2017 and 2018, ten years after the financial crisis, global interest rates remained low. For example, the ten-year US government bond yields fell below 3%, remained slightly above 1% in the UK, were approximately 0.40% in Germany, and were close to zero in Japan (Del Negro et al. 2019).

This decline in interest rates is a threat to insurance businesses, especially life insurance companies (Berdin and Gründl 2015; Grosen and Jørgensen 2000). Life insurers typically rely on fixed income markets, such as government and corporate bonds, to hedge their future obligation’s returns and gather sufficient funds to repay policyholders’ benefits. Several insurers use duration matching for hedging interest rate risk in periods of stability and near historical average risk, in line with US and European practices in early 2000 (Hartley et al. 2016). However, hedging interest rate risk is more complicated in a low interest rate environment, primarily due to the guaranteed interest rate and policyholder behaviors (Hartley et al. 2016). Over the past few decades, numerous life insurers have faced difficulties due to high guaranteed interest rates, despite hedging practices. Equitable Life, a British life insurer, was forced to shut down for new business following a House of Lords ruling in 2000 (Van der Heide 2020). The same year, German Mannheimer Lebensversicherung had to stop their new business underwriting due to financial distress (Schmeiser and Wagner 2015).

3. Materials and Methods

We employed a literature review methodology to gather various perspectives and information regarding different practices worldwide (Cronin and George 2020), enhancing the current knowledge regarding the impact of persistently low interest rates on the life insurance business, synthesizing the related literature, and highlighting critical areas for future research and reviews (Cronin and George 2020). Furthermore, we summarized the life insurance literature, systematizing the extant knowledge base (Whittemore and Knafl 2005). We aim to synthesize key findings from previous literature and compare insurance with lessons learned from the banking industry. Therefore, this review aims to better understand persistent low interest rates and their impact on the life insurance business.

We searched the titles, abstracts, and keywords of articles related to life insurance and low interest rate environments in the Scopus database. Only articles related to “life insurance,” “low interest (rates),” “interest rate risk,” “interest rate guarantee,” and “minimum interest rate” were included. Then, we reviewed these articles, working papers, and discussion papers and integrated them using Google Scholar and institution and online publisher websites to analyze the global interest rate trend. Only a few search results were relevant to the prolonged interest rate environment, highlighting the interest rate risk that matches the topical focus of the present review. Both quantitative and qualitative literature is included in the present review. The potential risk of bias in all included studies is alleviated by a reconciliation of conclusions between each country, as all countries should share a common paradigm regarding the same prolonged low interest rate phenomenon.

4. Results

This study adopts a qualitative approach. It reviews extant research and classifies it into three broad categories. The first literature stream addresses the impact of low interest rates on life insurance products, investigating the interest rate sensitivity of each product type and product shift strategy. The second branch in the literature examines the effects of low interest rates on life insurance companies’ valuations, addressing the shift in the valuation interest rate (VIR) and the financial and solvency impacts. Finally, the third research stream explores short- and long-term solutions for life insurers operating in low interest rate environments.

4.1. Impacts of Low Interest Rates on Life Insurance Products

Life insurance products have two prominent features. One is the protection coverage at which compensation is paid to the policyholder in the form of a lump-sum payment (sum assured) following an adverse event (i.e., death, accident, or sickness). The other is the saving component, which allows wealth accumulation for policyholders (Berends et al. 2013). In most developed countries, retirement or pension funds receive excess savings from the elderly (Reyna et al. 2022).

The interest rates on savings that life insurers guarantee to policyholders are a critical dimension (Hartley et al. 2016). Eling and Holder (2013b) classified the measures of guaranteed interest rates into two broad approaches. The first is an actuarial approach to analyzing different products’ risks and surplus appropriation schemes using an objective probability measure. Empirical studies comparing various products and surplus allocations employ this actuarial approach (Cummins et al. 2007; Grosen and Jørgensen 2000; Kling et al. 2007). The second approach emphasizes the fair price of product participation and the value of the embedded options. Both methods help assess the guaranteed interest rate of life insurance products (Eling and Holder 2013b).

Products previously priced at guaranteed high investment returns, often without any assets backing liability, may lead to a loss in the investment’s source of profit for insurance companies. A high guaranteed rate is consistent with the Association of Mexico Insurance Companies’ evidence that investment returns are the primary source of income for insurers (Reyna et al. 2022). Hence, insurers typically seek other sources of profits to compensate for policy reserves and achieve the required profit. Due to the high competition in the insurance industry, insurance products are complex and move quickly regarding the product development approach (Holsboer 2000). However, it is difficult to sell products profitably in a low interest rate environment unless a mark-up in prices or lower benefits are guaranteed from the insurance product design features. However, such a product may be less attractive to potential customers (Hartley et al. 2016).

Regulators in several jurisdictions, including the European Union and Japan, have set up a maximum allowable guaranteed interest rate, with an upper limit not exceeding 60% of the government bond’s yield (Schmeiser and Wagner 2015). In addition, the European Union directives relieve the impact of low interest rates, aligning them with the market interest rate movements. Regarding pricing strategies, regulators worldwide treat policyholders’ perspectives as critical considerations for approving life insurance products. According to Schmeiser and Wagner (2015), policyholders believe that insurers’ transaction costs, such as distribution and administration costs, are passed on to them. This concern has, in turn, induced insurers to better communicate with policyholders, reassuring them that transaction costs are acceptable.

4.1.1. Interest Rate Sensitivity of Each Product Type

Different types of businesses experience different impacts from interest rate movements. Non-life insurance (i.e., property and casualty insurance) is less sensitive to interest rate variations, as these products are short-tail liabilities (Reyna et al. 2022). Besides, non-life insurers may adjust their product prices upon renewal. An adjustable renewal premium allows non-life insurers to charge a reasonable fee in line with the interest rate environment, thus reducing interest rate risk (Berends et al. 2013). In contrast to life insurance products, these are long-term instruments in terms of coverage and premium payment. Furthermore, life insurance products usually provide a guaranteed minimum return in the form of illustrated dividends, such as whole life products in the US (Rybka 2017). Hence, differences in product features determine the level of exposure to interest rate risk. “With-profit” (or participating) endowment and whole life products are interest-rate sensitive instruments. However, they are less susceptible to interest rate changes if the guarantee is paid at maturity (rather than annually), and no market value adjustment is allowed, with assets backing liabilities, as in the case of Italian products (Focarelli 2015). On the contrary, in France, where minimum guaranteed rates are set lower than those in other European countries, profit-sharing, or a surplus appropriation scheme, plays a crucial role to meet policyholders’ expectations (Borel-Mathurin et al. 2018).

A different mixture of life, outliving, and saving elements characterizes insurance products. For example, while the outliving benefit is crucial for annuity and pension products, the saving benefit is vital for tax privileges or tax-benefit deduction purposes. These essential elements help assess insurers’ exposure to interest rate risk. The effects of the guaranteed minimum return on saving benefits and policyholders’ behavior are complex and reflect the interest rate sensitivity of life insurers. Upon interest rate changes, policyholders exercise their available options. For instance, they may surrender an annuity with a low guaranteed interest rate if the interest rate increases. By contrast, they may contribute more to that annuity product when the interest rate decreases (Hartley et al. 2016).

In the US, indexed universal life products usually provide a projected guaranteed interest rate as per the sale illustration at the moment of sale (Rybka 2017). In addition, equity-linked instruments successfully passing most investment risk onto policyholders are popular and high-growth products, with potential upside returns during stock market booms (Holsboer 2000).

Concerning pension and annuity products, German deferred annuity products provide a significant guarantee in the accumulation and annuity payout phases (Nieder 2016). With an annuity, policyholders receive protection against late death and a stream of future lifetime payments upon survival in return for earlier premium payments (Berends et al. 2013). Group pension products with an extended liability duration require more investment earnings from life insurers’ assets than individual products to adequately fund their retirement benefits, especially in a prolonged low interest rate environment (Holsboer 2000).

Grosen and Jørgensen (2000) performed a numerical analysis to disaggregate the features of traditional participating life insurance products into three baseline components. The first component is a risk-free bond representing the value of the guaranteed interest rate. The second component is the bonus (or dividend) option, and the last is the surrender option. The last two components are implicit options embedded in participating products. In the US, participating products typically combine these three components. This combined view is consistent with the approach that North American insurers view dividends as a release of an original price-benefit structure and return part of that premium in case it is no longer needed for future risks to policyholders (Bowers et al. 1997). However, only the first two components are usually present in European participating products, as the maturity bonus only applies to European life insurance companies (Grosen and Jørgensen 2000). Moreover, when an insurer’s investment return is insufficient to generate profit-sharing in participating products, they must resort to their equity capital (Kablau and Wedow 2012).

4.1.2. Product Shift Strategy

A high interest rate increases the demand for savings products, possibly resulting in a high rate of lapse or surrender of insurance policies for alternative investments. By contrast, a low interest rate hurts insurance companies’ profitability due to the low investment return on their asset backing portfolio (Eling and Holder 2013a). For life insurers, even a simple product, such as a whole life product, has an embedded saving element, such as a cash value that policyholders receive upon contract termination. This cash value usually builds up during the pre-maturity period until the contractual death or survival benefit payouts. In the absence of a pre-maturity event, the cash value grows until the maturity payment (Berends et al. 2013). Besides receiving death benefit coverage during the policy lifetime, life insurance policies allow policyholders to exercise embedded options. For instance, they may cease premium payments by using their cash value or dividends to pay for the due premium (Love and Miller 2013). Doing so, their policy remains in force. Hence, the cash value benefits policyholders, especially in the presence of declining interest rates.

Product portfolio composition is the primary consideration for determining an insurer’s shortfall risk (Bohnert et al. 2015). Product mix and its surplus appropriation scheme for participating products play a crucial role for life insurers and regulators. Focarelli (2015) showed that Italian life insurance companies mainly propose interest-sensitive products, such as participating endowment and whole life products. These single-premium products have a guaranteed maturity bonus. However, several insurers have moved their product portfolio toward the least investment return, or even no-guarantee products. In 2014, evidence regarding the new business portfolio showed that one-third of the sales volume moved toward new “dynamic hybrid” products, supporting a shift in products toward a combination of participating endowment and unit-linked features (Focarelli 2015).

Insurers focus on transferring the investment risk to policyholders, with the recent product trend moving toward variable life insurance products (Nieder 2016). For instance, German life insurers have moved from traditional savings and deferred annuity products to protection products (e.g., disability income benefits and long-term care products) and the “alternative guarantee” concept. This concept lowers the guarantee to only the return on premiums at the end of the deferred period and minimizes annuity payouts during the annuity phase (Nieder 2016).

4.2. The Impact on Valuation of Life Insurance Companies

Berends et al. (2013) applied a quantitative approach to analyze the sensitivity of life insurance companies to interest rate risk before the financial crisis (2002–2007) and during the low interest rate period of 2007 to 2012. Since the value of the insurer’s current balance sheet and future profits are represented by the insurer’s stock price, they examine an insurer’s exposure to interest rate risk by addressing the correlation between changes in interest rates and an insurer’s stock price. Before the financial crisis, the stock price of insurance companies was uncorrelated with benchmark government bond yields. However, it negatively correlated with bond yields after the crisis, when the interest rate dropped. Upon the decline in interest rates, bond prices increased. Empirical evidence from 26 publicly traded US life insurance companies has shown that large insurers (measured in terms of total assets) experienced a negative correlation between stock prices and bond yields. In addition, stock returns of large life insurers fluctuate more than those of small insurers because large life insurers have more interest-rate-sensitive life insurance products in their portfolio (Berends et al. 2013).

4.2.1. The Shift in Valuation Interest Rate

Valuation interest rate (VIR) or actuarial interest rate, namely, the technical interest rate, is “a conservative estimate of future investment earnings” (Holsboer 2000, p. 42). The technical interest rate helps in the valuation of reserves in a company’s balance sheet. Since the VIR is used as a discount rate for reserve calculation, the greater the VIR, the smaller the reserve amount (Eling and Holder 2013a). This is in line with Lidstone’s theorem, whereby the reserve to be held for a life insurance policy decreases with an increase in interest (Macdonald 2004). Regulators in various countries have set an upper limit for the VIR and named it the “maximum technical interest rate,” typically subject to an annual review for its adequacy as an implicit determiner of the minimum guaranteed interest rate for policyholders (Eling and Holder 2013a). The German regulator determines the maximum allowable interest rate for the reserve calculation and the pricing of new life insurance products in that country (Nieder 2016).

Insurers use reserves to allocate an additional interest provision and maintain policyholders’ future obligations, in line with the legally prescribed reserve methodology (Kablau and Weiß 2014). If the guaranteed interest rate exceeds the VIR at policy contract inception, insurers are typically expected to hold higher reserves than those priced in the contract. Eling and Holder (2013a) called this case an “undesirable positive initial reserve,” since the insurer must be pre-financed. However, when the guaranteed interest rate is less than the VIR, an opposite case of the negative initial reserve emerges, which is not recognized in the balance sheet, even though insurance companies consider it as a receivable (Eling and Holder 2013a).

The maximum VIR is regulated and driven by long-term government bond yields in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, where the maximum VIR entails a partially formula-based approach. In contrast, in the US, the VIR is fully formula-based and driven by corporate bond yields, without any regulator involvement (Eling and Holder 2013a). The situation is different in the UK, where the maximum VIR relies on a company-specific principle-based approach, rather than an explicit rule-based “one-size-fits-all” concept (Eling and Holder 2013a).

The German regulator has moved from relying on 60% of the past ten-year average of long-term nine- or ten-year (remaining) tenor government bond yields to the past five-year average to better reflect the current low interest rate scenario (Eling and Holder 2013a). Similarly, the Austrian regulator has set the maximum VIR at 2% since 1 April 2011. This rate is based on 60% of the ten-year average of the secondary market of Austrian government bond yields. Along these lines, Switzerland (a non-European Union country) has set the maximum VIR at 1.5% since 1 January 2012 (Eling and Holder 2013a).

In the US, the VIR follows the so-called “Commissioner’s Reserve Valuation Method” (Eling and Holder 2013a). According to the Standard Valuation Law, the maximum statutory VIR differs by product type and cohort year based on the average US investment-grade corporate bond yields. The VIR used at the policy inception date remains unchanged until the contract’s maturity date; this clause applies to the VIR of all the mentioned countries (Eling and Holder 2013a).

By contrast, the maximum VIR in the UK is determined from current and expected future earnings on insurance company-specific investment strategies, with sufficient allowance for margins in the case of an adverse deviation. The maximum VIR varies by product category. For example, the maximum VIR for traditional life insurance products (long-term) should not exceed 97.5% of the risk-adjusted return, assuming these liabilities are asset-backed (Eling and Holder 2013a).

Holsboer (2000) showed that a 2% VIR was applied for new life insurance business products in Japan and the European Union in the year 2000. This low VIR reflects the fact that the capital market interest rate was less than the products’ guaranteed interest rate at that time. Regulators worldwide have started to adjust the maximum VIR based on solvency assessments and exposure to low interest rate environments (Holsboer 2000). Eling and Holder (2013a) contributed to the research using stochastic simulation and a principle-based approach to capture company-specific risk. They emphasized that the VIR should continue to decrease in the future. Japan’s life insurers addressed this issue by moving their asset allocation toward USD-denominated bonds, particularly in the presence of negative returns on government bonds (Nieder 2016). Berends et al. (2013) contended that life insurers use derivatives, such as interest rate swaps, for hedging interest rate risk despite their limited proportions.

4.2.2. The Financial and Solvency Impacts

Love and Miller (2013) mentioned one primary source of profit for insurance companies, called “spread compression.” This spread reflects insurers’ gain from investment portfolios over and above the benefits policyholders receive for insurance policies. Even though some insurers may choose their targeted spreads to maintain profit at a manageable level, they cannot sustain those spread positions due to their products’ minimum guaranteed credit rates (Love and Miller 2013). For example, assume that the new product’s guaranteed interest rate is 2–3%, whereas the old business block (old products) has a minimum of 4%. An insurer may no longer be able to keep the targeted spread of 1.5% if investment returns only amount to 4.5%. Thus, insurers must delay an increase in the policy credit (interest rate) until they can recover the investment spread (Love and Miller 2013). As new money rates earned on insurers’ investment portfolios reflect the market interest rate environment, the life insurance policy credit (declared rate) lags behind new money rates (Love and Miller 2013).

Based on Lidstone’s theorem, the change in reserve of life insurance products and interest rate changes move in the opposite direction (Macdonald 2004). As such, low interest rates also extensively worsen the solvency position of life insurers due to an increase in reserves that insurers must hold. During 1997–2001, with the protracted low interest rate environment, seven middle-sized life insurers in Japan declared insolvency due to a drastic decline in the profitability of high guaranteed interest rates for their in-force business (Berdin and Gründl 2015). Nieder (2016) contended that a combination of negative spread, increased competition, and loss of customer confidence in those seven insurers led to insolvency. The European Union insurance regulators first developed a prescribed solvency regime called the “Solvency I (SI)” framework to address this issue. The regime required insurers to hold 4% of the premium reserve and 0.3% of the capital at risk as a solvency margin or regulatory own fund requirements (Kablau and Weiß 2014). Kablau and Weiß (2014) used coverage ratio, the ratio of eligible regulatory own funds to solvency margin, to measure the impact of low interest rates on insurers’ solvency. Results indicate that all German life insurers can manage their SI own funds requirements in the base scenario, whereas almost 40% will not be able to do so by 2023 under a severe low yield stress scenario.

Like Basel III1 in the banking industry, “Solvency II” (SII, henceforth) is a recent risk-based framework governed by insurance regulators. It applies a market-consistent approach to improve the transparency and stability of the financial system in the European Union. The SII standards set aside solvency over a one-year horizon based on a full range of risks on insurance companies’ asset and liability sides in the 99.5 percentile—a one in two hundred years loss event (Niedrig 2015). SII helps guard against insurance products with a minimum guaranteed interest rate. However, the more significant regulatory capital requirement set for this type of product makes them less likely to be promoted by life insurers (Paetzmann 2011). Holsboer (2000) contended that life insurers should set the risk-adjusted return on capital as a determinant for the minimum capital that life insurers should hold for different businesses based on their risk profiles. The riskier the business, the higher capital insurers should hold aside from high-profit investment to compensate for business risk (Holsboer 2000).

Marked-to-market, on both assets and liabilities, is a prerequisite for a market-consistent valuation of the solvency position under SII (Berdin and Gründl 2015). The discount rate reduction due to declining market bond yields increases the present value of future benefits and the market-consistent value of liabilities (Niedrig 2015). Since the liability duration is usually much longer than the duration of assets (Hartley et al. 2016), the higher this gap, the greater the reinvestment risk faced by insurers. These duration gaps lead to a potential issue in the insurer’s solvency position, as an insurance company’s asset values are lower than the market-consistent value of liabilities (Nieder 2016).

From 2009 to 2013, the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) emphasized the financial stability risk for insurance and pension companies, especially during a persistently low interest rate environment (Focarelli 2015). The EIOPA implemented a low interest rate stress test (called a “Japanese-like scenario”) in 2014 to test the sustainability of interest rate guarantees embedded in life insurance products. In addition, the EIOPA addressed the solvency capital requirement (SCR) ratio,2 interest rate exposures (measured in terms of duration or cash flow matching), and profitability (measured in terms of internal rate of return). According to Focarelli (2015), product design and segregated funds allow insurers to compute booked and realized values in Italy, assuring relatively stable and non-volatile returns. As a result, the Italian insurance industry’s SCR ratio outperforms the European average.

The International Accounting Standards specify that equity holding should be determined at market value, whereas liabilities must reflect book values. These requirements may lead to a solvency issue in a prolonged low interest rate environment (Holsboer 2000). When insurers adjust their assets’ portfolio quicker than the growth rate of liabilities to provide the high guarantee promised to policyholders, in a low interest rate environment, they increase their asset allocation to a riskier asset class. This asset reallocation makes liabilities more volatile than assets, requiring substantial capital to support businesses (Niedrig 2015). Risky investments are more vulnerable to disruption and variations in earnings. Hence, this shift toward risky investment may adversely impact insurers’ financial stability (Kablau and Weiß 2014). The riskier the high yield investments, the wider the duration gap between assets and liabilities, and the higher the volatility of asset portfolios. Berends et al. (2013) contended that life insurers might be exposed to credit risk on high-yield investments due to the potential loss of their asset values. This credit risk makes regulators worldwide (including in the US) enforce a risk-based capital (RBC) framework to help mitigate potential threats to insurance companies. Similar to the SII, the RBC framework establishes a minimum required capital that a life insurer must hold to assure solvency (Berends et al. 2013).

The required capital increases with higher risk charges. Empirical evidence from Niedrig (2015) indicates that changes in the long-term interest rate affect the insurer’s optimal risk portfolio by adding riskier asset classes in search of yields. As in the case of Germany, life insurers aim to increase the asset allocation to more illiquid investments, such as infrastructure bonds, to obtain higher yields (Nieder 2016). This investment strategy increases risk-taking to enhance investment returns and meet policyholders’ obligations (Kablau and Weiß 2014). By contrast, insurers’ asset portfolio is invested in risk-free government bonds upon a long-run upward increase in the interest rate. Hence, a narrowed duration gap leads to a decrease in the capital requirement for insurers.

Berdin and Gründl (2015) enhanced the balance sheet approach (market value) to summarize the key findings of the Deutsche Bundesbank regarding stress scenarios to quantify the impact of interest rate on life insurer solvency during a prolonged low interest rate period. The Financial Stability Review produced by the Deutsche Bundesbank (2013) showed that more than one-third of all German life insurers will not meet the regulatory capital requirements by 2023, based on a market-consistent balance sheet model. High guaranteed interest offered to policyholders is the main threat to insurers’ solvency. By contrast, Kablau and Weiß (2014) analyzed the impact of a low interest rate environment on the solvency of German life insurers using scenario analysis. Even though they consider the SI regime, all baseline, mild, and severe stress tests help visualize net investment returns for those situations, besides identifying a coverage ratio required to fulfill their own funds’ requirements.

4.3. Solution Approaches

Insurers worldwide take plausible actions to deal with a prolonged low interest rate environment. This study summarizes them into short- and long-term solutions.

4.3.1. Short-Term Solutions

US insurers have previously reduced the interest component of their dividend crediting rate as a prudent response to a low interest rate environment (Rybka 2017). Nieder (2016) emphasized the recent move toward USD-, Euro-, or AUD-denominated life insurance policies in Japan to promise a much higher guaranteed interest rate than that denominated in the local currency. However, this approach may expose policyholders to exchange rate risk.

From the product implementation perspective, insurers respond to the prolonged low interest rate environment by lowering the guaranteed interest rate on new products (Antolin et al. 2011). In addition, insurers react differently depending on the product type. For example, Love and Miller (2013) compared and contrasted potential corrective courses of action to alleviate the impact of prolonged low interest rates, which differ between in-force and new business blocks, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Impact of Each Product in a Prolonged Low Interest Rate Environment (adapted from Love and Miller 2013).

However, customers’ reactions to the insurer’s choices may vary. Therefore, insurers should help policyholders fully understand their decisions (Love and Miller 2013).

Concerning short-term financial monitoring, life insurers use ALM monitoring to assess and mitigate interest rate risk by lengthening the duration of assets (Holsboer 2000). Unlike banking institutions, they typically employ the ALM framework for long-term strategic management (Romanyuk 2010). We recognize that a potentially different approach could be caused by the varying nature of longer-term assets than liabilities for banks versus shorter-term assets than liabilities for life insurance. ALM is an investment approach based on matching asset and liability durations, helping insurers confine potential exposures to interest rate risk (Berends et al. 2013). Raising equity might also be necessary during a prolonged low interest rate environment, as it is the quickest approach to gathering sufficient equity funds (Kablau and Weiß 2014). We would emphasize that life insurers should balance meeting policyholders’ reasonable expectations and maintaining enough equity capital. This is partially supported by empirical evidence from Borel-Mathurin et al. (2018), who investigated the main drivers of the participating strategies of French life insurers. The econometric analyses showed that the average participation rate is essentially determined by the government bond rate and the insurer’s asset return. Upon decreasing interest rates, insurers should make long-term investments and lock in asset duration. This will lower the duration gap between life insurance liabilities and assets. Duration gap management helps protect life insurers’ equity capital (Paetzmann 2011). By contrast, when interest rates rise, life insurers must quickly invest in shorter-duration assets to meet policyholders’ expectations (Paetzmann 2011). Under the ALM framework, apart from the duration matching approach, we noted that several strategies and techniques are employed, depending on the life insurer’s objective. For example, cash flow matching is applied to minimize the difference between asset and liability cash flows or immunization (Redington 1952; Shiu 1987, 1988) and to maintain the surplus from asset and liability portfolios with fixed cashflows (Van der Meer and Smink 1993). Besides, the dedication approach to economically match cashflows within a boundary that sufficient cashflows could be paid out for incurred liabilities (Dahl 1993) is a quantitative solution largely adopted in practice.

4.3.2. Long-Term Solutions

The long-term view emphasizes the strategic implications of potential solutions for life insurers to respond to a prolonged low interest rate environment. Insurance companies seem reluctant to provide a high guaranteed return on their new products from a product development perspective (Holsboer 2000). Moreover, German life insurers have adopted alternative guaranteed product concepts in the form of a return of paid premiums or minimum annuity payouts, plus payout from profit-sharing or participating products. An example of an alternative product concepts is the guaranteed return of premiums for deferred annuities at the end of the deferral period (Nieder 2016).

Concerning the future product mix, Paetzmann (2011) emphasized the need for adjustments in the product mix of insurers’ portfolios to move away from guaranteed interest rate products and reduce the explicit and implicit impacts of guaranteed interest rates. Many insurers focus on selling more unit-linked products, transferring investment risk to policyholders (Holsboer 2000). Focarelli (2015), supported the role of linked-type products and proposed asset reallocation (mainly corporate and structured bonds) and new premiums to achieve sustainable minimum interest rate guarantees in a prolonged low interest rate environment.

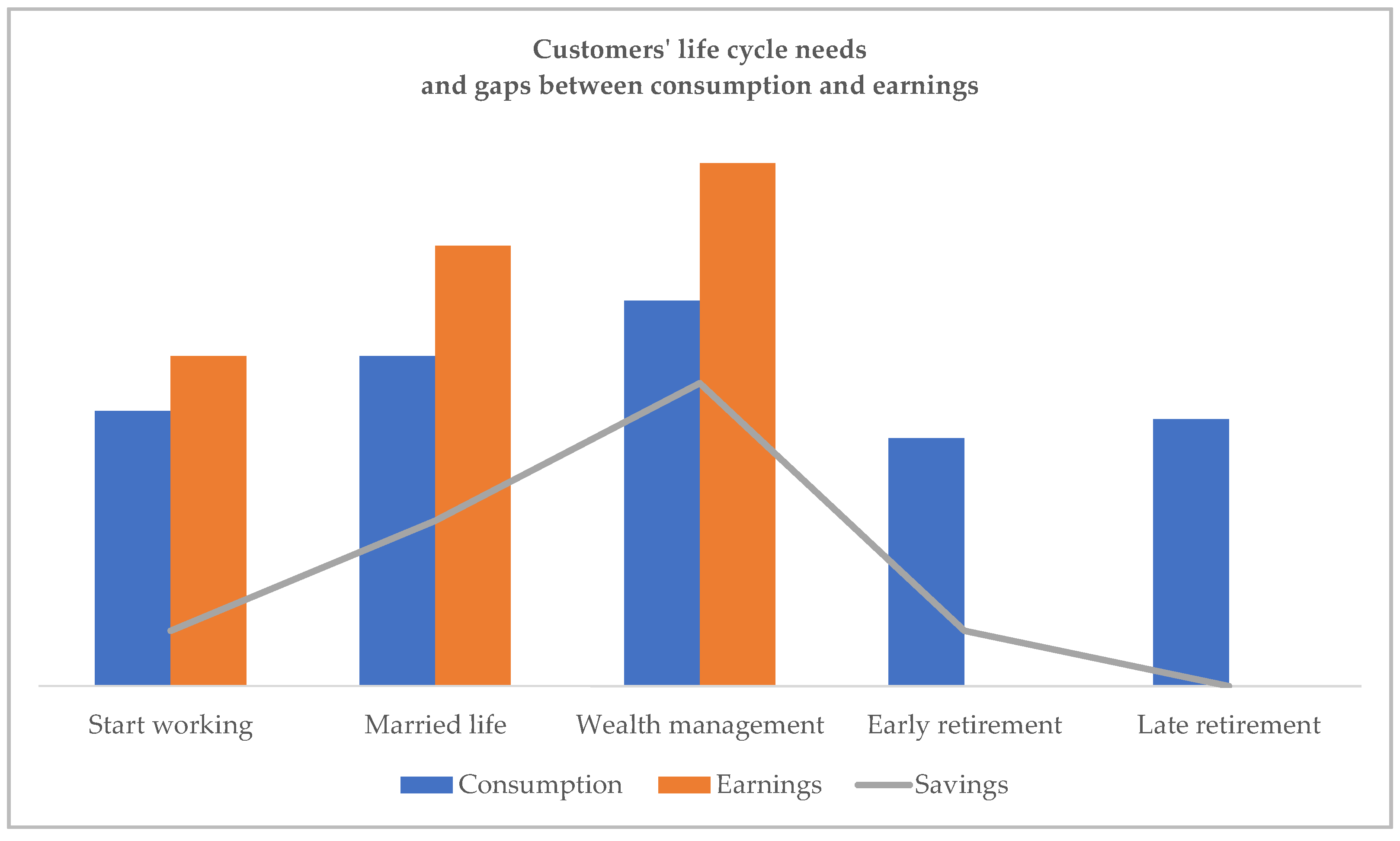

Japan and Germany moved toward selling more protection-oriented services due to their low claims. These protection-oriented products are disability income, medical insurance, cancer insurance, and long-term care products (Nieder 2016), which best suit customers’ needs in aging societies. In addition, Focarelli (2015) suggested moving toward new product features based on customers’ life cycle needs to fill the gap between consumption and earnings (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Customers’ Life Cycle Needs (adapted from Focarelli 2015).

Concerning financial impacts, Rybka (2017) recommended implementing reasonable economic assumptions for the expected credit rates, consistent with the forecast of asset portfolio earned rates. This assumption aligns the policyholder’s reasonable expectations with the market interest rate environment. In addition, insurers should implement an active monitoring policy, especially targeting the deviation of actual credit rates or dividend scales from expected rates.

Some insurers focus on increasing their response efficiency to compensate for revenue compression when their investment yields decrease (Holsboer 2000). Capital efficiency is significantly high when insurers switch their business portfolio to products with no minimum guaranteed interest rate (Wieland 2017). Holsboer (2000) highlighted that insurers are aware of the need to actively manage financial risk and assess life insurance companies’ profitability. In addition, insurers should measure market risk, which reflects the potential loss due to unfavorable market movements based on value-at-risk (VaR). The VaR indicator uses various statistics to assess price movements in financial securities (Holsboer 2000).

Bohnert et al. (2015) emphasized surplus appropriation schemes as effective tools to deal with shortfall risk in shareholder values. They substantially impact the guaranteed interest rates embedded in products offered to policyholders. Various schemes of surplus appropriation exist for determining fair dividend rates, including an increase in surplus appropriation for the remainder of the coverage period, an increase in the following benefit payout, and interest-bearing accumulation schemes. These schemes affect the dynamics of assets and liabilities for insurers (Bohnert et al. 2015). Thus, insurers should seek proper duration matching between asset and liability portfolios (Antolin et al. 2011).

5. Discussion

This literature review aimed to identify the impact of a prolonged low interest rate risk on life insurers’ pricing and valuation, proposing potential short and long-term solutions for life insurance companies. The protracted low interest rate environment requires life insurers to move their business mix toward non-interest-rate-sensitive products and lower their reliance on investment income (Focarelli 2015). Life insurers tend to transfer investment risk to policyholders (Nieder 2016). Regulators in several countries require annual reviews to establish an adequate upper limit of the VIR (Eling and Holder 2013a) and implement SII and RBC risk-based frameworks governed by global insurance regulators, requiring life insurers to hold the capital needed to guarantee solvency (Berends et al. 2013).

5.1. Limitations

This review primarily focused on the appraisal of past crises, their significant impacts, and potential solutions. Studies obtained from the Scopus database and Google Scholar focusing on the life insurance business during the recent persistent low interest rate period were examined. Thus, its findings rely on a limited number of studies and only apply to the life insurance business. Indeed, the literature base on the topic is limited, and there has also been little research regarding this topic in the past five years.

Moreover, the review solely examined key common characteristics from broad types of life insurance products available in the market worldwide. Therefore, any new initiatives or products are not considered in this review.

Finally, this research was conducted throughout a persistently low interest rate environment, which might have reached an (unforeseeable) end in the second quarter of 2022.

5.2. Interpretation and Implications of the Study’s Findings

Life insurers struggle to pay guaranteed contractual obligations in a prolonged low interest rate environment and maintain a solid financial position in terms of profitability and solvency (Berdin and Gründl 2015). Insurers may struggle to survive with a substantial existing in-force business block unless they set an optimal mix between their products’ saving and protection components. Numerical analysis (Eling and Holder 2013b) emphasizes that interest rate sensitivity increases when life insurers continually maintain an existing practice of guaranteed rate setting in their products. Further evidence was provided by research from Kablau and Weiß (2014), pointing out that German life insurers will no longer by able to manage their SI own funds requirements by 2023, given a low yield stress scenario. Hence, life insurers must take prudent actions to support their product portfolio and capital resilience.

While low market interest rates incentivize life insurers to invest in risky investments (Berdin and Gründl 2015), this scenario may also represent an opportunity to reshape their strategies and enhance their efficiency. Further analysis of the relationships among life insurance product types, the returns of the asset portfolio, and the solvency of life insurers may clarify the regulatory impact on and determinants of insurers’ financial stability.

Future research should consider Asian and emerging markets, mostly ignored by extant studies, addressing the impact of prolonged low interest rates on life insurers’ financial stability and solvency in these countries. Future interest rate trends, especially in emerging markets, are under the pressure of persistently low interest rates, partially from excess savings and a lack of investment opportunities (Reyna et al. 2022). Potential future development of alternative product designs might appeal to life insurers who seek lower interest rate risk, increased profitability, and improved capital efficiency, as mentioned by Wieland (2017). In addition, with the upcoming new international financial reporting standards, IFRS 17 (insurance contracts) and IFRS 9 (financial instruments), liabilities from insurance contracts and assets from financial instruments have become more closely connected. These standards may generate more pressure on life insurers in terms of profitability, as IFRS 9 and IFRS 17 adopt a forward-looking perspective. Last, the new reporting standards impact earnings volatility differently, depending on insurers’ balance sheet management choices and whether changes in fair values relate to profit and loss statements or other comprehensive income statements (Hogendoorn 2019).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.S. and S.Z.; methodology, W.S. and S.Z.; software, W.S. and S.Z.; validation, W.S. and S.Z.; formal analysis, W.S. and S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, W.S. and S.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.Z.; visualization, W.S. and S.Z.; supervision, S.Z.; project administration, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a publicly accessible repository.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Basel III is an international regulatory accord rolled out by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision to govern the banking sector’s ability to improve risk management and promote transparency. It sets appropriate risk-based capital as a cushion to deal with financial distress and maintain the continuity of bank operations (Bloomenthal 2020). |

| 2 | Solvency capital available based on eligible own funds (post-stress) divided by SCR (pre-stress). |

References

- Antolin, Pablo, Sebastian Schich, and Juan Yermo. 2011. The Economic Impact of Protracted Low Interest Rates on Pension Funds and Insurance Companies. OECD Journal: Financial Market Trends 1: 237–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdin, Elia, and Helmut Gründl. 2015. The Effects of a Low Interest Rate Environment on Life Insurers. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance-Issues and Practice 40: 385–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berends, Kyal, Robert McMenamin, Thanases Plestis, and Richard J. Rosen. 2013. The Sensitivity of Life Insurance Firms to Interest Rate Changes. Economic Perspectives 37: 47–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomenthal, Andrew. 2020. Basel III. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/basell-iii.asp (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Bohnert, Alexander, Nadine Gatzert, and Peter Løchte Jørgensen. 2015. On the Management of Life Insurance Company Risk by Strategic Choice of Product Mix, Investment Strategy and Surplus Appropriation Schemes. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 60: 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borel-Mathurin, Fabrice, Pierre-Emmanuel Darpeix, Quentin Guibert, and Stéphane Loisel. 2018. Main Determinants of Profit-Sharing Policy in the French Life Insurance Industry. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance-Issues and Practice 43: 420–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borri, Nicola, Rosaria Cerrone, Rosa Cocozza, and Domenico Curcio. 2018. Life Insurers’ Asset-Liability Dependency and Low-Interest Rate Environment. In Mathematical and Statistical Methods for Actuarial Sciences and Finance. Edited by Marco Corazza, María Durbán, Aurea Grané, Cira Perna and Marilena Sibillo. Cham: Springer, pp. 185–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, Newton L., Jr., Hans U. Gerber, James C. Hickman, Donald A. Jones, and Cecil J. Nesbitt. 1997. Actuarial Matehmatics. Schaumurg: The Society of Actuaries, pp. 512–15. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Z. Margaret, and Lawrence Galitz. 1982. Inflation and Interest Rates: A Research Study Using the ASIR Model. Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance. Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance 7: 290–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, Matthew A., and Elizabeth George. 2020. The Why and How of the Integrative Review. Organizational Research Methods. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. David, Kristian R. Miltersen, and Svein-Arne Persson. 2007. International Comparison of Interest Rate Guarantees in Life Insurance Contracts. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1071863 (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Dahl, Henrik. 1993. A Flexible Approach to Interest-Rate Risk Management. In Financial Optimization. Edited by Stavros A. Zenios. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 189–209. [Google Scholar]

- Del Negro, Marco, Domenico Giannone, Marc P. Giannoni, and Andrea Tambalotti. 2019. Global Trends in Interest Rates. Journal of International Economics 118: 248–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Bundesbank. 2013. Financial Stability Review 2013. Frankfurt am Main: Deutsche Bundesbank. [Google Scholar]

- Eling, Martin, and Stefan Holder. 2013a. Maximum Technical Interest Rates in Life Insurance in Europe and the United States: An Overview and Comparison. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance-Issues and Practice 38: 354–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eling, Martin, and Stefan Holder. 2013b. The Value of Interest Rate Guarantees in Participating Life Insurance Contracts: Status Quo and Alternative Product Design. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 53: 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Focarelli, Dario. 2015. ALM with Ultra-Low Interest Rates–(Life) Insurance Perspective. Available online: https://www.suerf.org/docx/l_1f0e3dad99908345f7439f8ffabdffc4_1475_suerf.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Grosen, Anders, and Peter Løchte Jørgensen. 2000. Fair Valuation of Life Insurance Liabilities: The Impact of Interest Rate Guarantees, Surrender Options, and Bonus Policies. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 26: 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, Daniel, Anna Paulson, and Richard J. Rosen. 2016. Measuring Interest Rate Risk in the Life Insurance Sector. The Economics, Regulation, and Systemic Risk of Insurance Markets, 124–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hogendoorn, Timo. 2019. An Introduction to IFRS 9 and IFRS 17. Available online: https://ifrs17explained.com/2019/08/09/an-introduction-to-ifrs-9-and-ifrs-17/ (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Holsboer, Jan H. 2000. The Impact of Low Interest Rates on Insurers. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance. Issues and Practice 25: 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kablau, Anke, and Matthias Weiß. 2014. How Is the Low Interest Rate Environment Affecting the Solvency of German Life Insurers? Available online: https://www.bundesbank.de/en/publications/reports/financial-stability-reviews/list-of-references-768388 (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Kablau, Anke, and Michael Wedow. 2012. Gauging the Impact of a Low Interest Rate Environment on German Life Insurers. Applied Economics Quarterly 58: 279–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kling, Alexander, Andreas Richter, and Jochen Ruß. 2007. The Impact of Surplus Distribution on the Risk Exposure of With Profit Life Insurance Policies Including Interest Rate Guarantees. Journal of Risk & Insurance 74: 571–89. [Google Scholar]

- LePan, Nicholas. 2019. The History of Interest Rates over 670 Years. Available online: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/the-history-of-interest-rates-over-670-years/ (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Love, Tom, and William C. Miller. 2013. Repercussions of a Sustained Low Interest Rate Environment on Life Insurance Products. Journal of Financial Service Professionals 67: 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, Angus S. 2004. Lidstone’s Theorem. In Encyclopedia of Actuarial Science. Edited by Jozef L. Teugels and Bjørn Sundt. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 978–79. [Google Scholar]

- Nieder, Dirk. 2016. The Impact of the Low Interest Rate Environment on Life Insurance Companies. Reinsurance News 87: 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Niedrig, Tobias. 2015. Optimal Asset Allocation for Interconnected Life Insurers in the Low Interest Rate Environment Under Solvency Regulation. Journal of Insurance Issues 38: 31–71. [Google Scholar]

- Paetzmann, Karsten. 2011. Discontinued German Life Insurance Portfolios: Rules-In-Use, Interest Rate Risk, and Solvency II. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance 19: 117–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redington, Frank M. 1952. Review of the Principles of Life-Office Valuations. Journal of the Institute of Actuaries 78: 286–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyna, Ana M., Hugo J. Fuentes, and José A. Núñez. 2022. Response of Mexican Life and Non-life Insurers to the Low Interest Rate Environment. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance-Issues and Practice 47: 409–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanyuk, Yulia. 2010. Asset-Liability Management: An Overview. Discussion Papers 10-10. Ottawa: Bank of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Rybka, Lawrence J. 2017. Impact of Low Interest Rates on the Insurance Industry. Estate Planning 44: 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Schmeiser, Hato, and Joël Wagner. 2015. A Proposal on how The Regulator Should Set Minimum Interest Rate Guarantees in Participating Life Insurance Contracts. Journal of Risk and Insurance 82: 659–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiu, Elias S. W. 1987. Immunization—The Matching of Assets and Liabilities. In Actuarial Science. Edited by Ian B. MacNeill and Gary J. Umphrey. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing, pp. 145–56. [Google Scholar]

- Shiu, Elias S. W. 1988. Immunization of Multiple Liabilities. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 7: 219–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trading Economics. 2022. United States Fed Funds Rate. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/united-states/interest-rate (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Van der Heide, Arjen. 2020. Making Financial Uncertainty Count: Unit-Linked Insurance, Investment and the Individualisation of Financial Risk in British Life Insurance. The British Journal of Sociology 71: 985–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Meer, Robert, and Meye Smink. 1993. Strategies and Techniques for Asset-Liability Management: An Overview. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance-Issues and Practice 18: 144–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, Robin, and Kathleen Knafl. 2005. The Integrative Review: Updated Methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 52: 546–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieland, Jochen. 2017. Runoff or Redesign? Alternative Guarantees and New Business Strategies for Participating Life Insurance. European Actuarial Journal 7: 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).