National Culture and Corporate Rating Migrations

Abstract

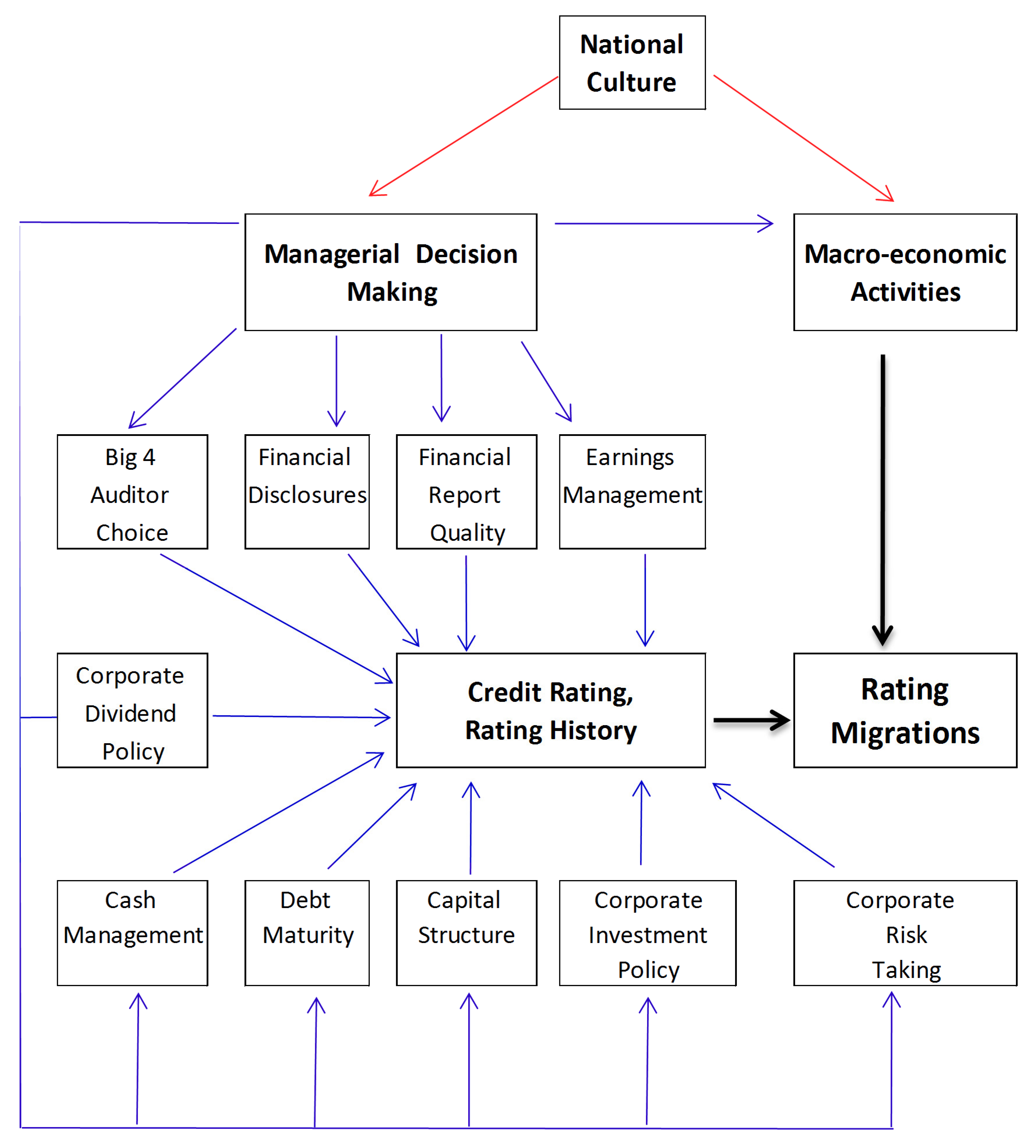

:1. Introduction

2. National Culture and Corporate Rating Migrations

2.1. Rating Data

2.2. Culture Data

2.3. Culture Dimensions

2.3.1. Power Distance Index (PDI) or Hierarchy

2.3.2. Individualism (IDV) versus Collectivism (Embeddedness)

2.3.3. Masculinity (MAS) versus Femininity

2.3.4. Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI)

2.3.5. Long-Term (LT) versus Short-Term (ST) Orientation

3. Models and Variables

3.1. Estimation Model

3.2. Variables

3.3. Samples

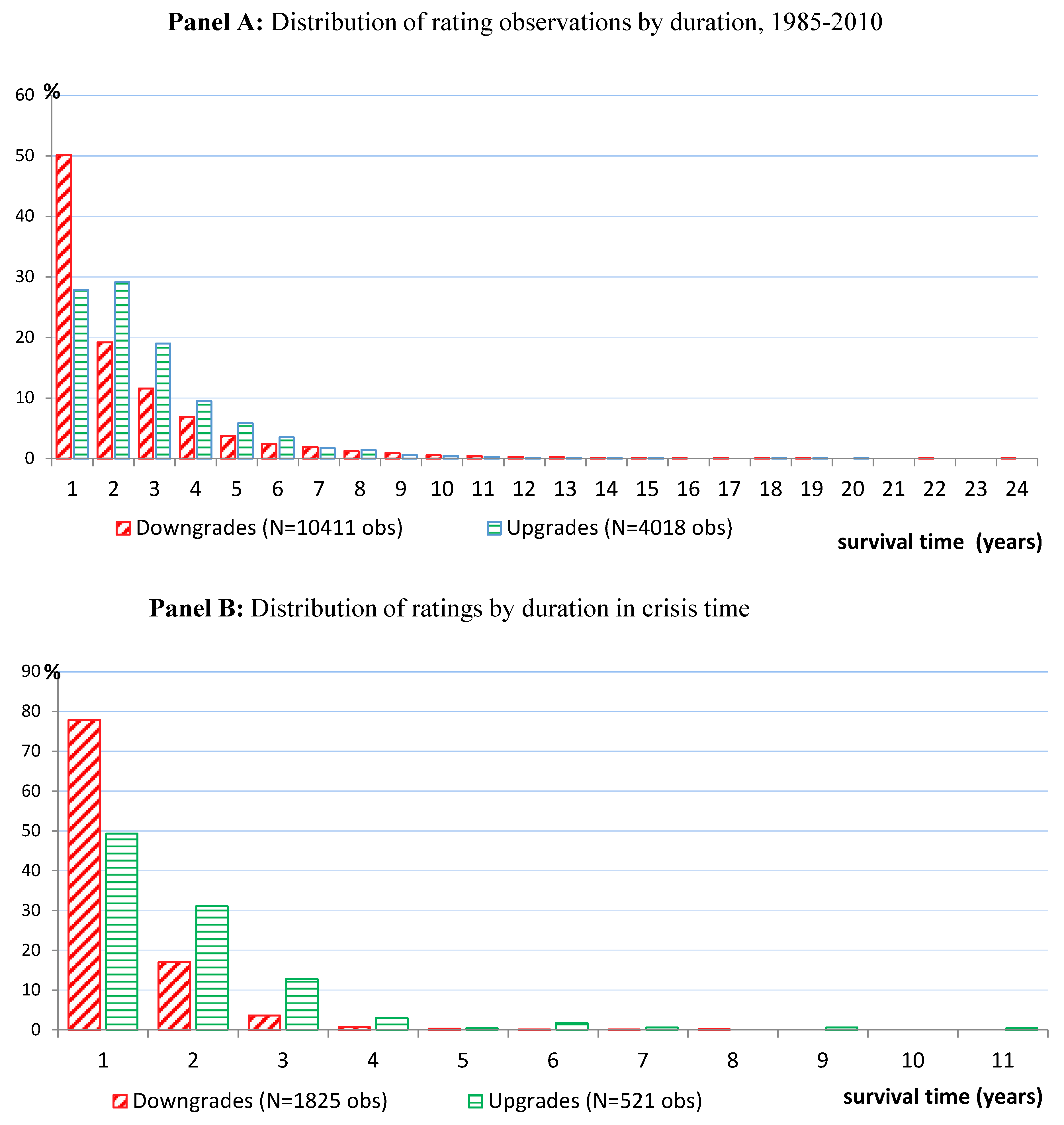

3.4. Statistics

4. Results

4.1. Models for the Whole Sample (Samples A(H) and A(H-S))

4.2. Robustness Tests

4.2.1. Models for Non-U.S. Firms (Samples B(H) and B(H-S))

4.2.2. Models for Crisis and Non-Crisis Periods (Samples C(H-1), C(H-2), C(H-3))

4.2.3. Other Robustness Tests

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A.

References

- Afego, Pyemo N. 2018. Index shocks, investor action and long-run stock performance in Japan: A case of cultural behaviouralism? Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 18: 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, Paul D. 1995. Survival Analysis Using SAS: A Practical Guide. Cary: SAS Institute Inc., ISBN 978-1-59994-884-3. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, Edward. 1998. The importance and subtlety of credit rating migration. Journal of Banking and Finance 22: 1231–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, Edward I., and Duen L. Kao. 1992. The implications of corporate bond rating drifts. Financial Analysts Journal 48: 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Christopher W., Mark Fedenia, Mark Hirschey, and Hilla Skiba. 2011. Cultural influences on home bias and international diversification by institutional investors. Journal of Banking and Finance 35: 916–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, Badar N., Changjun Zheng, and Sidra Arshad. 2016. Effects of national culture on bank risk-taking behavior. Research in International Business and Finance 27: 309–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Sung C., Kiyoung Chang, and Eun Kang. 2012. Culture, corporate governance and dividend policy: International evidence. The Journal of Financial Research 35: 289–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangia, Anil, Francis X. Diebold, André Kronimus, Christian Schagen, and Til Schuermann. 2002. Rating Migrations and the Business Cycle, with Applications to Credit Portfolio Stress Testing. Journal of Banking and Finance 26: 445–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, Brad M., and Terrance Odean. 2001. Boys will be boys: Gender, overconfidence and common stock investment. Quarterly Journal of Economics 116: 261–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, Marshall E., Donald B. Keim, and Sandeep A. Patel. 1991. Returns and volatility of low-grade bonds, 1977–1989. Journal of Finance 46: 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubakri, Narjess, Ali Mirzaei, and Anis Samet. 2017. National culture and bank performance: Evidence from the recent financial crisis. Journal of Financial Stability 29: 36–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, James P., David C. Miller, and William Schafer. 1999. Gender Differences in Risk Taking: A Meta-Analysis. Psychology Bulletin 75: 367–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carty, Lee V., and Jerome S. Fons. 1994. Measuring Changes in Corporate Credit Quality. Journal of Fixed Income 4: 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Chih-Hsiang, and Shih-Jia Lin. 2015. The effects of national culture and behavioral pitfalls on investors’ decision-making: Herding behavior in international stock markets. International Review of Economics and Finance 37: 380–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Kiyoung, and Abbas Noorbakhsh. 2009. Does national culture affect international corporate cash holdings? Journal of Multinational Financial Management 19: 323–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, Andy, Alison E. Lloyd, and Chuck C. Y. Kwok. 2002. The determination of capital structure: Is national culture a missing piece to the puzzle? Journal of International Business Studies 33: 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jeffrey R., Laurie W. Pant, and David J. Sharp. 1996. A methodological note on cross-cultural accounting ethics research. International Journal of Accounting 31: 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, David R. 1972. Regression models and life tables. Journal of Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 34: 187–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Huong, and Graham Partington. 2014. Rating migrations: The effects of rating history and time. ABACUS 50: 174–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mooij, Marieke. 2004. Consumer Behaviour and Culture: Consequence for Global Marketing and Advertising. Thousand Oaks: Sage, ISBN 9781412979900. [Google Scholar]

- De Paoli, Bianca, Glenn Hoggarth, and Victoria Saporta. 2009. Output Costs of Sovereign Crises: Some Empirical Estimates. Bank of England Working Paper No. 362. Available online: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/working-paper/2009/output-costs-of-sovereign-crises-some-emperical-estimates.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2018).

- Desender, Kurt A., Christian E. Castro, and Sergio A. Escamilla De Leon. 2011. Earnings management and cultural values. American Journal of Economics and Sociology 70: 639–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doupnik, Timothy S., and George T. Tsakumis. 2004. A critical review of tests of Gray’s theory of cultural relevance and suggestions for future research. Journal of Accounting Literature 23: 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri, Giovanni, Li-gang Liu, and Joseph E. Stiglitz. 1999. The procyclical role of rating agencies: Evidence from the East Asian crisis. Economic Notes 28: 335–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidrmuc, Jana P., and Marcus Jacob. 2010. Culture, agency costs and dividends. Journal of Comparative Economics 38: 321–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figlewski, Stephen, Halina Frydman, and Weijian Liang. 2012. Modeling the Effects of Macroeconomic Factors on Corporate Default and Credit Rating Transitions. International Review of Economics and Finance 21: 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, Ana R., and Francisco Gonzalez. 2008. Cross country determinants of bank income smoothing by managing loan-loss provisions. Journal of Banking and Finance 32: 217–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Sidney. 1988. Towards a theory of cultural influence on the development of accounting systems internationally. ABACUS 24: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Sidney J., and Hazel M. Vint. 1995. The impact of culture on accounting disclosures: Some international evidence. Asia Pacific Journal of Accounting 21: 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, Dale, Omrane Guedhami, Chuck C. Y. Kwok, Kai Li, and Liang Shao. 2015. National Culture, Corporate Governance Practices and Firm Performance. Working Paper. Available online: https://memento.epfl.ch/public/upload/files/Paper_Li.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2018).

- Guiso, Luigi, Helios Herrera, and Massimo Morelli. 2016. Cultural differences and institutional integration. Journal of International Economics 99: 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güttler, André. 2011. Lead-lag Relationships and Rating Convergence among Credit Rating Agencies. Journal of Credit Risk 7: 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güttler, André, and Mark Wahrenburg. 2007. The adjustment of credit ratings in advance of defaults. Journal of Banking and Finance 31: 751–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Sam, Tony Kang, Stephen Salter, and Yong Keun Yoo. 2010. A cross-country study on the effects of national culture on earnings management. Journal of International Business Studies 41: 123–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Paula, Robert Brooks, and Robert Faff. 2010. Variations in sovereign credit quality assessments across rating agencies. Journal of Banking and Finance 34: 1324–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, Geert. 1980. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills: Sage, ISBN 9780803913066. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, Geert. 2001. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations. Thousand Oaks: Sage, ISBN 9780803973244. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, Geert, Geert Hofstede, and Michael Minkov. 2010. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0071664189. [Google Scholar]

- Hope, Ole-Kristian. 2003. Firm-level disclosures and the relative roles of culture and legal origin. Journal of International Financial Management and Accounting 14: 218–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, Ole-Kristian, Tony Kang, Wayne Thomas, and Yong Keun Yoo. 2008. Culture and auditor choice: A test of the secrecy hypothesis. Journal of Accounting Public Policy 27: 357–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, David W., Stanley Lemeshow, and Susanne May. 2008. Applied Survival Analysis: Regression Modeling of Time-to-Event Data, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley, ISBN 978-0-471-75499-2. [Google Scholar]

- Husted, Bryan. 1999. Wealth culture and corruption. Journal of International Business Studies 3: 339–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Michael, and William Meckling. 1976. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Richard. 2004. Rating agency actions around the investment grade boundary. Journal of Fixed Income 13: 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, James, and Tomasz Lenartowicz. 1998. Culture freedom and economic growth: Do cultural values explain economic growth? Journal of World Business 33: 332–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorion, Philippe, Charles Shi, and Sanjian Zhang. 2009. Tightening Credit Standards: The Role of Accounting Quality. Review of Accounting Study 14: 123–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagaretnam, Kiridaran, Chee Yeow Lim, and Gerald Lobo. 2011. Effects of National Culture on Earnings Quality of Banks. Journal of International Business Studies 42: 853–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, Chuck C. Y., and Solomon Tadesse. 2006. National culture and financial systems. Journal of International Business Studies 37: 227–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laeven, Luc, and Fabian Valencia. 2008. Systemic Banking Crises: A New Database. IMF Working Paper WP/08/224. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2008/wp08224.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2018).

- Lando, David, and Torben M. Skodeberg. 2002. Analyzing ratings transitions and rating drift with continuous observations. Journal of Banking and Finance 26: 423–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Kwok, Rabi S. Bhagat, Nancy R. Buchan, Miriam Erez, and Cristina B. Gibson. 2005. Culture and international business: Recent advances and their implications for future research. Journal of International Business Studies 36: 357–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Zhichuan. 2016. Endogeneity in CEO power: A survey and experiment. Investment Analysts Journal 45: 149–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Kai, Dale Griffin, Heng Yue, and Longkai Zhao. 2013. How does culture influence corporate risk-taking? Journal of Corporate Finance 23: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Licht, Amir, Chanan Goldschmidt, and Shalom Schwartz. 2005. Culture, law and corporate governance. International Review of Law and Economics 25: 229–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, Gerald, Luc Paugam, Herve Stolowy, and Pierre Astolfi. 2017. The Effect of Business and Financial Market Cycles on Credit Ratings: Evidence from the Last Two Decades. ABACUS 53: 59–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manasse, Paolo, Nouriel Roubini, and Axel Schimmelpfennig. 2003. Predicting Sovereign Debt Crisis. IMF Working Paper 03/221. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/30/Predicting-Sovereign-Debt-Crises-16951 (accessed on 2 November 2018).

- Mann, Christopher, David Hamilton, Praveen Varma, and Richard Cantor. 2003. What Happens to Fallen Angels? A Statistical Review 1982–2003. Moody’s Investor Service Special Comment. Available online: https://www.moodys.com/sites/products/DefaultResearch/2002000000425343.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2018).

- Mora, Nada. 2006. Sovereign credit ratings: Guilty beyond reasonable doubt? Journal of Banking and Finance 30: 2041–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickell, Pamela, William Perraudin, and Simone Varotto. 2000. Stability of ratings transitions. Journal of Banking and Finance 24: 203–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, Douglass. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521397346. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Yihui, Stephen Siegel, and Tracy Yue Wang. 2017. Corporate Risk Culture. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 52: 2327–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, Angel A. P., and Clark Wheatley. 2017. The influence of culture on real earnings management. International Journal of Emerging Markets 12: 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers. 2008. Reward: A New Paradigm? Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/banking-capital-markets/pdf/reward.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2018).

- Ramirez, Andrés, and Solomon Tadesse. 2009. Corporate Cash Holdings, Uncertainty Avoidance and the Multinationality of Firms. International Business Review 18: 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S&P Global Ratings’ Credit Research. 2013. Default Study: Sovereign Defaults and Rating Transition Data, 2012 Update. New York: Alacra Store. [Google Scholar]

- S&P RatingsDirect. 2009. Use of CreditWatch and Outlooks. September 14. Available online: http://www.maalot.co.il/publications/MT20131212112758c.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2018).

- S&P RatingsDirect. 2013. Corporate Methodology. November 19. Available online: https://www.spratings.com/scenario-builder-portlet/pdfs/CorporateMethodology.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2018).

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 1994. Beyond Individualism-Collectivism: New Dimensions of Values. In Individualism and Collectivism: Theory, Method and Application. Edited by Uichol Kim, Harry C. Triandis, Çiğdem Kâğitçibaşi, Sang-Chin Choi and Gene Yoon. Thousand Oaks: Sage, ISBN 978-0803957633. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Liang, Chuck C. Y. Kwok, and Omrane Guedhami. 2010. National culture and dividend policy. Journal of International Business Studies 41: 1391–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Liang, Chuck C. Y. Kwo, and Ran Zhang. 2013. National culture and corporate investment. Journal of International Business Studies 44: 745–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Linghui, and Peter Koveos. 2008. A framework to update Hofstede’s cultural value indices: Economic dynamics and institutional stability. Journal of International Business Studies 39: 1045–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titman, Sheridan. 1984. The effect of capital structure on a firm’s liquidation decision. Journal of Financial Economics 13: 137–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakumis, George, Anthony Curatola, and Thomas Porcano. 2007. The relation between national cultural dimensions and tax evasion. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation 16: 131–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazza, Diane, Devi Aurora, and Ryan Schneck. 2005a. Crossover Credit: A 24-Year Study of Fallen Angel Rating Behavior. New York: Standard & Poor’s Global Fixed Income Research. [Google Scholar]

- Vazza, Diane, Edward Leung, Marya Alsati, and Mike Katz. 2005b. Credit Watch and Ratings Outlooks: Valuable Predictors of Rating Behaviour. New York: Standard & Poor’s Global Fixed Income Research. [Google Scholar]

- Vitell, Scott, Saviour Nwachukwu, and James Barnes. 1993. The effects of culture on ethical decisions making: An application of Hofstede’s typology. Journal of Business Ethics 12: 753–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, Gary R. 2001. Ethics Programs in Global Businesses: Culture’s Role in Managing Ethics. Journal of Business Ethics 30: 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Lee-Jen, Danyu Lin, and Lisa Weissfeld. 1989. Regression analysis of multivariate incomplete failure time data by modelling marginal distributions. Journal of the American Statistical Association 84: 1065–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzeski, Marilyn T. 1996. Spontaneous harmonization effects of culture and market forces on accounting disclosure practices. Accounting Horizons 10: 18–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Xiaolan, Sadok Ghoul, Omrane Guedhami, and Chuck C. Y. Kwok. 2012. National culture and corporate debt maturity. Journal of Banking and Finance 36: 468–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Pan et al. acknowledge that they do not account for social influences and shared experience inside a firm, thus not capturing a firm’s risk culture entirely. |

| 2 | Contributing to this view is the evidence that the cultural differences between Greece and Germany made Greece’s negotiations to avoid a default much more difficult (Guiso et al. 2016). |

| 3 | For example, long-term oriented countries have a higher national saving rate and a higher growth rate. Individualistic countries achieve a higher GNI per capita (Hofstede et al. 2010, pp. 38, 263–65). |

| 4 | For the evidence of downward momentum in rating migration dynamics, see Altman and Kao (1992); Carty and Fons (1994); Altman (1998); Bangia et al. (2002); Lando and Skodeberg (2002); Güttler and Wahrenburg (2007); Figlewski et al. (2012); Dang and Partington (2014) |

| 5 | S&P rating scales were changed in 1983. To calculate the annual changes of employed macro-economic variables in 1985, the values in 1984 and 1985 were needed. Thus, 1985 was chosen as the starting year of the study. |

| 6 | Tang and Koveos (2008) suggest that institutional factors, such as language, religion, climate and legal origin, are subsumed by Hofstede’s uncertainty avoidance and masculinity traits. The correlations between Hofstede’s culture scores and other measures “do not tend to become weaker over time” (Hofstede et al. 2010, p. 39). |

| 7 | Embeddedness is referred to as conservatism in some studies, such as Johnson and Lenartowicz (1998); Chui et al. (2002); Shao et al. (2010). |

| 8 | An example is the handling of the Åland Islands crisis and the Falkland Islands crisis. The Åland Islands crisis was resolved by negotiations in 1921 between feminine countries Finland and Sweden. The Åland Islands remained Finnish but the pro-Swedish islands gained substantial regional autonomy. The Falklands Islands crisis in 1982 involved Argentinean military and British expeditionary forces. The crisis between two masculine countries cost “725 Argentinean and 225 British lives and enormous financial expense.” The Falklands Islands have remained a disputed territory and required “constant British subsidies and military presence” (Hofstede et al. 2010, p. 173). |

| 9 | Contributing to this view is the remark of the President of the European Commission José Manuel Barroso at the European Parliament in May 2010 that ratings are “too cyclical, too reliant on the general market mood rather than on fundamentals...”. |

| 10 | Strong UA countries are intolerant of political ideologies, are “more likely to harbor extremist minorities within their political landscape” and have more “native terrorists” (Hofstede et al. 2010, p. 221). |

| 11 | See, for example, Altman and Kao (1992); Carty and Fons (1994); Altman (1998); Bangia et al. (2002); Lando and Skodeberg (2002); Vazza et al. (2005b); Güttler and Wahrenburg (2007); Figlewski et al. (2012); Dang and Partington (2014). |

| 12 | Most static variables are updated annually. Return of world stock market index is calculated using daily data over a 63-trading day rolling window prior to the beginning of each rating. Dummy OECD member, dummy debt crisis and dummy prior default are updated at the beginning of each rating. |

| 13 | Subtracting one from the hazard ratio (HR) gives the change in risk for a one-unit change in the independent variable. Dummy LTO’s HR of 0.748 represents a 25.2% reduction in downgrade risk for firms in a LTO country (model 1). Dummy LTO (model 1) has a stronger impact than LTO (models 2 and 3). A larger effect of dummy LTO is not unusual in hazard modelling, often because a switch from short-term to long-term orientation represents a substantial change. |

| Variable | Definition | References |

|---|---|---|

| Hofstede’s culture dimensions Hofstede (1980) conducted surveys with IBM employees in over 50 countries and used the survey responses to identify four national culture dimensions that were virtually uncorrelated. In Hofstede et al. (2010), the scores on the four dimensions were listed for 76 countries. The fifth dimension, long-term versus short-term orientation, was introduced by Michael Bond in his Chinese Value Survey conducted in 23 countries in 1987, and extended to 93 countries in 2010 by Michael Minkov (Hofstede et al. 2010) | ||

| Power distance index | Power distance index expresses the degree to which members of a society accept and expect that power and authority is distributed unequally. | Licht et al. (2005); Hope et al. (2008); Hofstede et al. (2010); Fidrmuc and Jacob (2010); Kanagaretnam et al. (2011); Zheng et al. (2012); Paredes and Wheatley (2017) |

| Individualism vs. collectivism | Individualism encourages the pursuit of personal interests, autonomy and an active determination of one’s destiny. Collectivism stresses conformity and adherence to societal norms and regulations | Chui et al. (2002); Licht et al. (2005); Tsakumis et al. (2007); Fidrmuc and Jacob (2010); Han et al. (2010); Hofstede et al. (2010); Shao et al. (2010); Kanagaretnam et al. (2011); Zheng et al. (2012); Li et al. (2013); Shao et al. (2013) |

| Masculinity vs. femininity | Masculine countries strive for a performance society and value assertiveness, material accomplishment, ambition, competition and success. Feminine countries strive for a welfare society and value cooperation, modesty, caring for the weak and quality of life | Vitell et al. (1993); Chui et al. (2002); Licht et al. (2005); Hofstede et al. (2010); Anderson et al. (2011); Kanagaretnam et al. (2011); Zheng et al. (2012) |

| Uncertainty avoidance index | The uncertainty avoidance index expresses the degree to which the members of a society feel uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity. | Licht et al. (2005); Kwok and Tadesse (2006); Ramirez and Tadesse (2009); Tsakumis et al. (2007); Hope et al. (2008); Fidrmuc and Jacob (2010); Han et al. (2010); Hofstede et al. (2010); Anderson et al. (2011); Kanagaretnam et al. (2011); Zheng et al. (2012); Li et al. (2013) |

| Long-term vs. short-term orientation | Long-term oriented cultures are oriented toward the future and value perseverance and thrift. Short-term oriented societies foster virtues related to the past and present. | Cohen et al. (1996); Hofstede et al. (2010); Anderson et al. (2011) |

| Schwartz’s culture dimensions Schwartz (1994) collected survey data from school teachers and university students in more than 60 countries. He classified national cultures into six dimensions. Two dimensions embeddedness and hierarchy are employed in this study | ||

| Embeddedness (conservatism) | Embedded cultures value social relationships, emphasize maintaining the status quo and restraining actions that may disrupt in-group solidarity and traditional order | Johnson and Lenartowicz (1998); Chui et al. (2002); Licht et al. (2005); Shao et al. (2010); Zheng et al. (2012) |

| Hierarchy | Hierarchical cultures view the unequal distribution of power, roles, and wealth as legitimate and even desirable. | Chui et al. (2002); Licht et al. (2005); Zheng et al. (2012) |

| S&P’s ratingdata: Source: Standard & Poor’s Ratings Xpress | ||

| Current rating grade | The current rating (start rating) for the rating transition being observed. | Carty and Fons (1994); Figlewski et al. (2012); Dang and Partington (2014) |

| Investment rating boundary | The dummy takes the value of one if the current rating is in the investment grade boundary (BBB−, BBB, BBB+) or zero otherwise | Carty and Fons (1994); Johnson (2004); Dang and Partington (2014) |

| Junk rating boundary | The dummy takes the value of one if the current rating is in the speculative (junk) grade boundary (BB−, BB, BB+) or zero otherwise | Carty and Fons (1994); Johnson (2004); Dang and Partington (2014) |

| Logarithm of age since first rated | Age since first rated is a time-varying variable measuring the duration since a firm was first rated. This variable is updated whenever a migration of interest occurs in the sample | Altman (1998); Figlewski et al. (2012); Dang and Partington (2014) |

| Dummy lag one downgrade | The dummy takes the value of one if the lag one rating ends with a downgrade, and zero otherwise | Carty and Fons (1994); Lando and Skodeberg (2002); Bangia et al. (2002); Figlewski et al. (2012); Dang and Partington (2014) |

| Lag one duration (years) | The duration of the rating immediately preceding the current rating | Carty and Fons (1994); Lando and Skodeberg (2002); Dang and Partington (2014) |

| Dummy prior fallen angel | This variable takes the value of one if a firm had experienced a downgrade from an investment-grade rating to a speculative-grade rating as of the start of the current rating, and zero otherwise | Mann et al. (2003); Vazza et al. (2005a); Güttler and Wahrenburg (2007); Dang and Partington (2014) |

| Dummy large downgrade | This variable takes the value of one if a firm had experienced a big downgrade of at least three rating notches as of the start of the current rating, and zero otherwise | Carty and Fons (1994); Dang and Partington (2014) |

| Dummy large upgrade | This variable takes the value of one if a firm had experienced a big upgrade of at least three rating notches as of the beginning of the current rating, and zero otherwise | Dang and Partington (2014) |

| Rating volatility | This is the average number of migrations per year over a firm’s rating history. It is calculated as the number of migrations a firm had experienced as of the beginning of the current rating divided by age since first rated. | Dang and Partington (2014) |

| S&P’s outlook Source: Standard & Poor’s Ratings Xpress S&P issues an outlook to indicate its opinion regarding the potential direction of a long-term credit rating over the intermediate term (six months–two years) (S&P RatingsDirect 2009). Outlooks can be positive (rating may be raised), negative (rating may be lowered), stable (rating unlikely to change), or developing (rating may be raised/ lowered) | ||

| Dummy negative outlook | This time-varying variable takes the value of one if a firm was assigned a negative outlook by S&P, and zero otherwise. | Vazza et al. (2005a); Hill et al. (2010) |

| Dummy positive outlook | This time-varying variable takes the value of one if a firm was assigned a positive outlook by S&P, and zero otherwise. | Vazza et al. (2005a); Hill et al. (2010) |

| Macro-economic and financial conditions Source: World Bank databases unless otherwise stated | ||

| Dummy prior default | This dummy takes the value of one if a country where a firm resides had a foreign currency-denominated debt default prior to the start of the rating under study, and zero otherwise. Source: S&P Global Ratings’ Credit Research (2013) | Mora (2006); Hill et al. (2010) |

| Dummy debt crisis | This variable takes a value of one if a rating commences during a period of sovereign debt/ banking crisis as listed in Manasse et al. (2003), Laeven and Valencia (2008), or De Paoli et al. (2009), and zero otherwise. | Ferri et al. (1999); Mora (2006) |

| Dummy OECD member | This variable takes a value of one if the country where a firm resides is a member of the OECD at the start of the current rating, and zero otherwise. | Ferri et al. (1999); Mora (2006) |

| Logarithm of GDP per capita | The logarithm of real GDP per capita | Ramirez and Tadesse (2009); Zheng et al. (2012); Figlewski et al. (2012); Shao et al. (2013); Li et al. (2013); Dang and Partington (2014) |

| Change in real GDP growth rate | The change in the real GDP growth rate over the year prior to the start of the rating. | Ferri et al. (1999); Mora (2006); Hill et al. (2010); Shao et al. (2013) |

| Change in inflation | The change in the inflation rate over the year prior to the start of the rating. | Ramirez and Tadesse (2009); Zheng et al. (2012) |

| Change in current account surplus/GDP | The change in the current account surplus or deficit divided by GDP | Ferri et al. (1999); Mora (2006); Hill et al. (2010) |

| Change in term trade | The change in terms of trade. The terms of trade effect equals capacity to imports less exports of goods and services in constant prices. Data are in constant local currency. | |

| Logarithm of ratio stock market capitalization/GDP | The logarithm of the ratio of stock market capitalization to GDP | Zheng et al. (2012); Li et al. (2013); Shao et al. (2013) |

| Return of world stock market index | The average return of the World-Datastream stock market index, which is calculated using daily data over a 63-trading day rolling window prior to the start of the rating under study. Source: Datastream | Hill et al. (2010) |

| Political rights and civil liberties Source: International Country Risk Guide database. The political risk rating comprises the scores of 12 metrics including government stability, bureaucracy quality, corruption, democratic accountability, external conflict, ethnic tensions, internal conflict, investment profile, law and order, military in politics, religion in politics, and socioeconomics conditions. | ||

| Dummy high political risk | This dummy takes a value of one if a country’s political rating score is less than or equal to 40, and zero otherwise 40 | |

| Dummy low political risk | This dummy takes a value of one if a country’s political rating score is higher than or equal to 80, and zero otherwise. | |

| Panel A: Statistics of S&P’s Numerical Rating Grades | |||

| Sample A(H): All Firms | Sample B(H): Non-US Firms | Sample C(H-1): Crisis Sample | |

| Sample size | 17,109 | 4745 | 3927 |

| Mean | 10.29 | 11.08 | 8.79 |

| Median | 10 (BB) | 11 (BB+) | 8 (B+) |

| Std dev | 4.18 | 4.22 | 3.9 |

| Min | 1 (C) | 1 (C) | 2 (CC) |

| Max | 21 (AAA) | 21 (AAA) | 20 (AA+) |

| Panel B: Statistics of Survival Time for Downgrades | |||

| Sample A(H): All Firms | Sample B(H): Non-US Firms | Sample C(H-1): Crisis Sample | |

| Number of downgrades | 10,411 | 2661 | 1825 |

| Frequency of downgrades | 60.85% | 56.08% | 46.5% |

| Mean (years) | 1.82 | 1.55 | 0.66 |

| Median (years) | 1 | 0.92 | 0.38 |

| Std dev | 2.25 | 1.78 | 0.76 |

| Min (years) | ~ 0 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Max (years) | 23.43 | 14.28 | 7.41 |

| Panel C: Statistics of Survival Time for Upgrades | |||

| Sample A(H): All Firms | Sample B(H): Non-US Firms | Sample C(H-1): Crisis Sample | |

| Number of upgrades | 4018 | 1096 | 521 |

| Frequency of upgrades | 23.48% | 23.1% | 13.3% |

| Mean (years) | 2.25 | 1.99 | 1.34 |

| Median (years) | 1.74 | 1.55 | 1.01 |

| Std dev | 1.96 | 1.63 | 1.32 |

| Min (years) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Max (years) | 19.72 | 10.3 | 10.3 |

| Panel A: Descriptive Statistics of Culture Values for Samples A(H) and A(H-S) of All Firms | |||||

| Mean | Median | Std Dev | Min | Max | |

| Hofstede (H) culture values (N = 17,109) | |||||

| Power distance index (PDI) | 42.7 | 40 | 10.43 | 11 | 104 |

| Individualism vs. collectivism (IDV) | 83.26 | 91 | 17.64 | 12 | 91 |

| Masculinity vs. femininity (MAS) | 60.15 | 62 | 10.4 | 5 | 110 |

| Uncertainty avoidance index (UAI) | 50.28 | 46 | 13.46 | 8 | 112 |

| Long-term vs. short-term orientation (LTO) | 32.91 | 26 | 15.99 | 13 | 100 |

| Schwartz (S) culture values (N = 16,966) | |||||

| Embeddedness | 3.62 | 3.67 | 0.16 | 3.03 | 4.35 |

| Hierarchy | 2.34 | 2.37 | 0.17 | 1.49 | 3.23 |

| Panel B: Descriptive Statistics of Culture Values for Sample B(H) and B(H-S) of Non-U.S. Firms | |||||

| Mean | Median | Std Dev | Min | Max | |

| Hofstede (H) culture values (N = 4745) | |||||

| Power distance index (PDI) | 49.75 | 39 | 17.98 | 11 | 104 |

| Individualism vs. collectivism (IDV) | 63.08 | 71 | 23.63 | 12 | 90 |

| Masculinity vs. femininity (MAS) | 55.32 | 56 | 18.91 | 5 | 110 |

| Uncertainty avoidance index (UAI) | 61.44 | 53 | 21.94 | 8 | 112 |

| Long-term vs. short-term orientation (LTO) | 50.93 | 51 | 21.74 | 13 | 100 |

| Schwartz (S) culture values (N = 4602) | |||||

| Embeddedness | 3.49 | 3.46 | 0.27 | 3.03 | 4.35 |

| Hierarchy | 2.25 | 2.22 | 0.32 | 1.49 | 3.23 |

| Culture Dummy Mean (Hofstede, N = 17,109) | Numeric Culture Score (Hofstede, N = 17,109) | Numeric Score (Hofstede & Schwartz, N = 16,966) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downgrade (1) | Upgrade (1) | Downgrade (2) | Upgrade (2) | Downgrade (3) | Upgrade (3) | |||||||

| Variables | Coefficient | HR | Coefficient | HR | Coefficient | HR | Coefficient | HR | Coefficient | HR | Coefficient | HR |

| Hofstede’s national culture dimensions | ||||||||||||

| Power distance index (PDI) | NA | NA | −0.01 *** | 0.99 | NA | NA | ||||||

| Individualism vs. collectivism (IDV) | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

| Masculinity vs. femininity (MAS) | NA | NA | 0.004 ** | 1.004 | 0.006 *** | 1.006 | ||||||

| Uncertainty avoidance index (UAI) | NA | NA | 0.009 *** | 1.009 | 0.004 *** | 1.004 | ||||||

| Long-term vs. short-term orientation (LTO) | NA | NA | −0.009 *** | 0.991 | -0.011 *** | 0.989 | ||||||

| Dummy large power distance index | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

| Dummy individualism | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

| Dummy masculine | 0.17907 *** | 1.196 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||

| Dummy strong uncertainty avoidance | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

| Dummy long-term orientation | −0.29086 *** | 0.748 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||

| Schwartz’s national culture dimensions | ||||||||||||

| Embeddedness | NA | NA | NA | NA | −0.274 ** | 0.76 | ||||||

| Hierarchy | NA | NA | NA | NA | −0.353 *** | 0.702 | 0.552 *** | 1.737 | ||||

| S&P’s rating data | ||||||||||||

| Current rating grade | −0.01021 *** | 0.99 | −0.10447 *** | 0.901 | −0.009 ** | 0.991 | −0.106 *** | 0.9 | −0.01 ** | 0.99 | −0.108 *** | 0.898 |

| Investment rating boundary (BBB−/BBB/BBB+) | −0.23186 *** | 0.793 | 0.16734 *** | 1.182 | −0.241 *** | 0.786 | 0.167 *** | 1.182 | −0.24 *** | 0.786 | 0.164 *** | 1.179 |

| Junk rating boundary (BB−/BB/BB+) | 0.14226 *** | 1.153 | 0.143 *** | 1.154 | 0.141 *** | 1.152 | ||||||

| Dummy negative outlook (time-varying) | 0.29138 *** | 1.338 | −1.7834 *** | 0.168 | 0.285 *** | 1.33 | −1.783 *** | 0.168 | 0.282 *** | 1.326 | −1.776 *** | 0.169 |

| Dummy positive outlook (time-varying) | −1.73029 *** | 0.177 | 1.206 *** | 3.34 | −1.721 *** | 0.179 | 1.209 *** | 3.35 | −1.713 *** | 0.18 | 1.207 *** | 3.345 |

| Logarithm of age since first rated (time-varying) | −1.57095 *** | 0.208 | −1.45531 *** | 0.233 | −1.556 *** | 0.211 | −1.439 *** | 0.237 | −1.552 *** | 0.212 | −1.434 *** | 0.238 |

| Dummy lag one downgrade | 0.66822 *** | 1.951 | 0.659 *** | 1.933 | 0.665 *** | 1.945 | ||||||

| Lag one rating duration | 0.06974 *** | 1.072 | 0.03321 *** | 1.034 | 0.07 *** | 1.072 | 0.033 *** | 1.034 | 0.07 *** | 1.072 | 0.033 *** | 1.033 |

| Dummy prior fallen angel event(s) | −0.13936 *** | 0.87 | −0.137 *** | 0.872 | −0.119 *** | 0.888 | ||||||

| Dummy large downgrade | 0.15244 *** | 1.165 | 0.28276 *** | 1.327 | 0.171 *** | 1.187 | 0.285 *** | 1.33 | 0.163 *** | 1.177 | 0.281 *** | 1.325 |

| Dummy large upgrade | 0.088 * | 1.092 | ||||||||||

| Rating volatility | −0.05591 | 0.946 | −0.13391 *** | 0.875 | −0.053 | 0.948 | −0.134 *** | 0.874 | −0.051 | 0.951 | −0.135 *** | 0.874 |

| Macro-economic and financial conditions | ||||||||||||

| Dummy prior default | −0.47471 *** | 0.622 | −0.536 *** | 0.585 | −0.442 *** | 0.643 | −0.24 * | 0.787 | ||||

| Dummy debt crisis | −0.1048 * | 0.901 | −0.112 ** | 0.894 | ||||||||

| Dummy OECD member | 0.23915 *** | 1.27 | −0.249 *** | 0.78 | 0.306 *** | 1.358 | −0.269 *** | 0.764 | 0.212 * | 1.236 | ||

| Logarithm of GDP per capita | 0.164 ** | 1.178 | ||||||||||

| Change in real GDP growth rate | −0.02713 *** | 0.973 | −0.028 *** | 0.972 | −0.028 *** | 0.973 | ||||||

| Change in inflation | −0.02144 *** | 0.979 | −0.022 *** | 0.979 | −0.022 *** | 0.978 | ||||||

| Change in current account surplus/GDP | −0.04317 *** | 0.958 | 0.07859 *** | 1.082 | −0.04 *** | 0.961 | 0.079 *** | 1.082 | −0.044 *** | 0.957 | 0.069 *** | 1.071 |

| Change in term trade | ||||||||||||

| Logarithm of ratio stock market cap/GDP | −0.09241 *** | 0.912 | 0.06 *** | 1.062 | −0.078 *** | 0.925 | 0.08 *** | 1.083 | −0.161 *** | 0.852 | ||

| Return of world stock market index | −0.58725 *** | 0.556 | −0.24199 ** | 0.785 | −0.525 *** | 0.592 | −0.228 * | 0.796 | −0.532 *** | 0.588 | −0.251 ** | 0.778 |

| Political risks | ||||||||||||

| Dummy low political risk | 0.09715 *** | 1.102 | −0.08271 ** | 0.921 | 0.067 ** | 1.069 | −0.094** | 0.911 | 0.072 *** | 1.074 | −0.066 * | 0.936 |

| Dummy high Political risk | ||||||||||||

| Events/ sample size | 60.85% | 23.48% | 60.85% | 23.48% | 60.97% | 23.44% | ||||||

| Likelihood ratio χ2 | 8319.85 *** | 5022.41 *** | 8379.83 *** | 5017.3 *** | 8350.8 *** | 4977.2 *** | ||||||

| Culture Dummy Mean (Hofstede, N = 4745) | Numeric Culture Score (Hofstede, N = 4745) | Numeric Score (Hofstede & Schwartz, N = 4602) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downgrade (1) | Upgrade (1) | Downgrade (2) | Upgrade (2) | Downgrade (3) | Upgrade (3) | |||||||

| Variables | Coefficient | HR | Coefficient | HR | Coefficient | HR | Coefficient | HR | Coefficient | HR | Coefficient | HR |

| Hofstede’s national culture dimensions | ||||||||||||

| Power distance index (PDI) | NA | NA | −0.008 *** | 0.993 | NA | NA | ||||||

| Individualism vs. collectivism (IDV) | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

| Masculinity vs. femininity (MAS) | NA | NA | 0.003 * | 1.003 | 0.004 *** | 1.004 | 0.003 * | 1.003 | ||||

| Uncertainty avoidance index (UAI) | NA | NA | 0.004 *** | 1.004 | ||||||||

| Long-term vs. short-term orientation (LTO) | NA | NA | −0.007 *** | 0.993 | −0.008 *** | 0.992 | ||||||

| Dummy large power distance index | −0.37814 *** | 0.685 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||

| Dummy individualism | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

| Dummy masculine | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

| Dummy strong uncertainty avoidance | 0.17973 *** | 1.197 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||

| Dummy long-term orientation | −0.1631 *** | 0.85 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||

| Schwartz’s national culture dimensions | ||||||||||||

| Embeddedness | NA | NA | NA | NA | −0.448 *** | 0.639 | ||||||

| Hierarchy | NA | NA | NA | NA | −0.337 *** | 0.714 | ||||||

| S&P’s rating data | ||||||||||||

| Current rating grade | −0.10145 *** | 0.904 | −0.10145 *** | 0.904 | −0.103 *** | 0.902 | −0.102 *** | 0.904 | ||||

| Investment rating boundary (BBB−/BBB/BBB+) | 0.25624 *** | 1.292 | 0.25624 *** | 1.292 | −0.292 *** | 0.747 | 0.25 *** | 1.284 | −0.263 *** | 0.769 | 0.219 *** | 1.244 |

| Junk rating boundary (BB−/BB/BB+) | 0.17256 ** | 1.188 | 0.17256 ** | 1.188 | 0.17 ** | 1.185 | 0.16 ** | 1.173 | ||||

| Dummy negative outlook (time-varying) | −1.61499 *** | 0.199 | −1.61499 *** | 0.199 | 0.354 *** | 1.425 | −1.618 *** | 0.198 | 0.341 *** | 1.406 | −1.576 *** | 0.207 |

| Dummy positive outlook (time-varying) | 1.27989 *** | 3.596 | 1.27989 *** | 3.596 | −1.787 *** | 0.167 | 1.282 *** | 3.605 | −1.767 *** | 0.171 | 1.306 *** | 3.691 |

| Logarithm of age since first rated (time-varying) | −2.77147 *** | 0.063 | −2.77147 *** | 0.063 | −2.299 *** | 0.1 | −2.765 *** | 0.063 | −2.335 *** | 0.097 | −2.742 *** | 0.064 |

| Dummy lag one downgrade | −0.13508 ** | 0.874 | −0.13508 ** | 0.874 | 0.598 *** | 1.818 | −0.133 ** | 0.876 | 0.575 *** | 1.777 | −0.13 ** | 0.878 |

| Lag one rating duration | 0.15485 *** | 1.167 | 0.167 *** | 1.181 | 0.156 *** | 1.169 | 0.184 *** | 1.202 | 0.16 *** | 1.173 | ||

| Dummy prior fallen angel event(s) | 0.22181 ** | 1.248 | 0.227 ** | 1.255 | 0.174 ** | 1.19 | 0.225 ** | 1.253 | ||||

| Dummy large downgrade | ||||||||||||

| Dummy large upgrade | −0.24784 ** | 0.78 | −0.232 * | 0.793 | −0.189 | 0.828 | ||||||

| Rating volatility | −0.07356 | 0.929 | −0.21696 ** | 0.805 | −0.075 | 0.928 | −0.215 ** | 0.807 | −0.067 | 0.936 | −0.204 ** | 0.816 |

| Macro-economic and financial conditions | ||||||||||||

| Dummy prior default | −0.45461 *** | 0.635 | −0.4 *** | 0.671 | −0.391 *** | 0.676 | ||||||

| Dummy debt crisis | 0.16082 ** | 1.174 | 0.172 *** | 1.188 | 0.171 ** | 1.186 | ||||||

| Dummy OECD member | −0.191 ** | 0.826 | ||||||||||

| Logarithm of GDP per capita | ||||||||||||

| Change in real GDP growth rate | −0.02736 *** | 0.973 | −0.03 *** | 0.971 | −0.031 *** | 0.97 | ||||||

| Change in inflation | −0.016 *** | 0.984 | −0.01629 *** | 0.984 | −0.017 *** | 0.983 | −0.016 *** | 0.984 | −0.017 *** | 0.984 | −0.017 *** | 0.983 |

| Change in current account surplus/GDP | 0.03483 *** | 1.035 | 0.035 *** | 1.036 | 0.037 *** | 1.038 | ||||||

| Change in term trade | ||||||||||||

| Logarithm of ratio stock market cap/GDP | ||||||||||||

| Return of world stock market index | −0.60958 *** | 0.544 | −0.609 *** | 0.544 | −0.683 *** | 0.505 | ||||||

| Political risks | ||||||||||||

| Dummy low political risk | ||||||||||||

| Dummy high Political risk | ||||||||||||

| Events/ sample size | 56.08% | 23.1% | 56.08% | 23.1% | 56.37% | 22.92% | ||||||

| Likelihood ratio χ2 | 2858.04 *** | 1681.21 *** | 2874 *** | 1684.7 *** | 2860 *** | 1630.5 *** | ||||||

| Crisis Sample (Hofstede, N = 3927) | Non-Crisis Sample (Hofstede, N = 13,182) | Non-Crisis Non-U.S. Sample (Hofstede, N = 3714) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downgrade | Upgrade | Downgrade | Upgrade | Downgrade | Upgrade | |||||||

| Variables | Coefficient | HR | Coefficient | HR | Coefficient | HR | Coefficient | HR | Coefficient | HR | Coefficient | HR |

| Hofstede’s national culture dimensions | ||||||||||||

| Power distance index (PDI) | −0.019 *** | 0.981 | 0.00405 ** | 1.004 | ||||||||

| Individualism vs. collectivism (IDV) | ||||||||||||

| Masculinity vs. femininity (MAS) | 0.00442 *** | 1.004 | 0.00326 * | 1.003 | ||||||||

| Uncertainty avoidance index (UAI) | 0.009 *** | 1.009 | ||||||||||

| Long-term vs. short-term orientation (LTO) | −0.005 *** | 0.995 | 0.015 *** | 1.015 | −0.0068 *** | 0.993 | −0.00473 *** | 0.995 | ||||

| S&P’s rating data | ||||||||||||

| Current rating grade | −0.055 *** | 0.947 | −0.281 *** | 0.755 | −0.09783 *** | 0.907 | −0.105 *** | 0.9 | ||||

| Investment rating boundary (BBB−/BBB/BBB+) | −0.417 *** | 0.659 | 0.445 * | 1.56 | −0.21511 *** | 0.806 | 0.18773 *** | 1.207 | −0.22824 *** | 0.796 | 0.29756 *** | 1.347 |

| Junk rating boundary (BB−/BB/BB+) | 0.472 *** | 1.603 | 0.15556 *** | 1.168 | 0.17947 ** | 1.197 | ||||||

| Dummy negative outlook (time-varying) | 0.406 *** | 1.501 | −1.512 *** | 0.22 | 0.2374 *** | 1.268 | −1.93868 *** | 0.144 | 0.26543 *** | 1.304 | −1.97581 *** | 0.139 |

| Dummy positive outlook (time-varying) | −1.668 *** | 0.189 | 1.327 *** | 3.769 | −1.72525 *** | 0.178 | 1.17788 *** | 3.247 | −1.91491 *** | 0.147 | 1.20023 *** | 3.321 |

| Logarithm of age since first rated (time-varying) | −1.048 *** | 0.351 | −0.69 *** | 0.502 | −1.73288 *** | 0.177 | −1.47874 *** | 0.228 | −3.19282 *** | 0.041 | −2.99776 *** | 0.05 |

| Dummy lag one downgrade | 0.877 *** | 2.403 | 0.61724 *** | 1.854 | 0.58564 *** | 1.796 | ||||||

| Lag one rating duration | 0.066 *** | 1.068 | 0.07298 *** | 1.076 | 0.03799 *** | 1.039 | 0.18513 *** | 1.203 | 0.17943 *** | 1.197 | ||

| Dummy prior fallen angel event(s) | −0.19549 *** | 0.822 | 0.30926 *** | 1.362 | ||||||||

| Dummy large downgrade | 0.194 *** | 1.214 | 0.17731 *** | 1.194 | 0.32772 *** | 1.388 | 0.17525 | 1.192 | ||||

| Dummy large upgrade | 0.14199 *** | 1.153 | −0.26509 ** | 0.767 | ||||||||

| Rating volatility | −0.107 | 0.899 | −0.10982 ** | 0.896 | −0.46349 *** | 0.629 | −0.19194 ** | 0.825 | ||||

| Macro-economic and financial conditions | ||||||||||||

| Dummy prior default | −0.654 *** | 0.52 | ||||||||||

| Dummy OECD member | −1.008 *** | 0.365 | 0.28907 *** | 1.335 | 0.2497 *** | 1.284 | 0.42189 *** | 1.525 | ||||

| Logarithm of GDP per capita | 0.564 *** | 1.758 | ||||||||||

| Change in real GDP growth rate | −0.055 *** | 0.946 | ||||||||||

| Change in inflation | −0.019 *** | 0.981 | −0.027 *** | 0.973 | ||||||||

| Change in current account surplus/GDP | −0.063 *** | 0.939 | 0.142 *** | 1.152 | 0.04871 *** | 1.05 | ||||||

| Change in term trade | 0.000002 *** | 1 | 0.000037 *** | 1 | 0.00003 *** | 1 | ||||||

| Logarithm of ratio stock market cap/GDP | 0.11571 *** | 1.123 | −0.10045 *** | 0.904 | ||||||||

| Return of world stock market index | −0.367 *** | 0.693 | −0.61 *** | 0.544 | −0.45234 *** | 0.636 | −0.47447 *** | 0.622 | ||||

| Political risks | ||||||||||||

| Dummy low political risk | −0.198 *** | 0.82 | 0.11886 *** | 1.126 | -0.10071 ** | 0.904 | ||||||

| Dummy high Political risk | ||||||||||||

| Events/ sample size | 46.47% | 13.3% | 65.13% | 26.53% | 56.22% | 26.17% | ||||||

| Likelihood ratio χ2 | 1825.3 *** | 697 *** | 6808.65 *** | 4414.7 *** | 2367.02 *** | 1568.68 *** | ||||||

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dang, H.D. National Culture and Corporate Rating Migrations. Risks 2018, 6, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks6040130

Dang HD. National Culture and Corporate Rating Migrations. Risks. 2018; 6(4):130. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks6040130

Chicago/Turabian StyleDang, Huong Dieu. 2018. "National Culture and Corporate Rating Migrations" Risks 6, no. 4: 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks6040130

APA StyleDang, H. D. (2018). National Culture and Corporate Rating Migrations. Risks, 6(4), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks6040130