Retirees face significant financial risk and competing financial objectives.

Pfau (

2014) summarizes them as lifestyle, longevity, legacy, and liquidity. In retirement, individuals need steady income to fund their day-to-day expenses (lifestyle), they face the risk of outliving their retirement savings (longevity), they may wish to leave a bequest to heirs (legacy), and they must have reserves for healthcare costs or other unforeseen expenses (liquidity). They must construct and manage their portfolios to address both their need for secure lifetime income and wealth accumulation.

In the United States, employer-sponsored retirement plans fall broadly into two categories: Defined Benefit (DB) and Defined Contribution (DC). For both types of plans, employers and employees make contributions to fund future benefits. In a DB plan, the employee’s retirement benefit is calculated on the basis of factors such as age, length of service, final average salary, etc. The retirement benefits may be paid as a life annuity; thus, they offer retirees the prospect of a secure lifetime income. The employer manages the investment fund and assumes all investment and longevity risks. In a DC plan, the participants choose among a set of investment options according to their time horizon and risk tolerance. They contribute to their retirement account and, upon retirement, they must manage their nest egg to fund their retirement. Because of the upside potential of equities markets, DC plans offer the potential for significant wealth accumulation. However, the plan participant bears all of the investment and longevity risk and thus might have insufficient income in retirement or might outlive their savings.

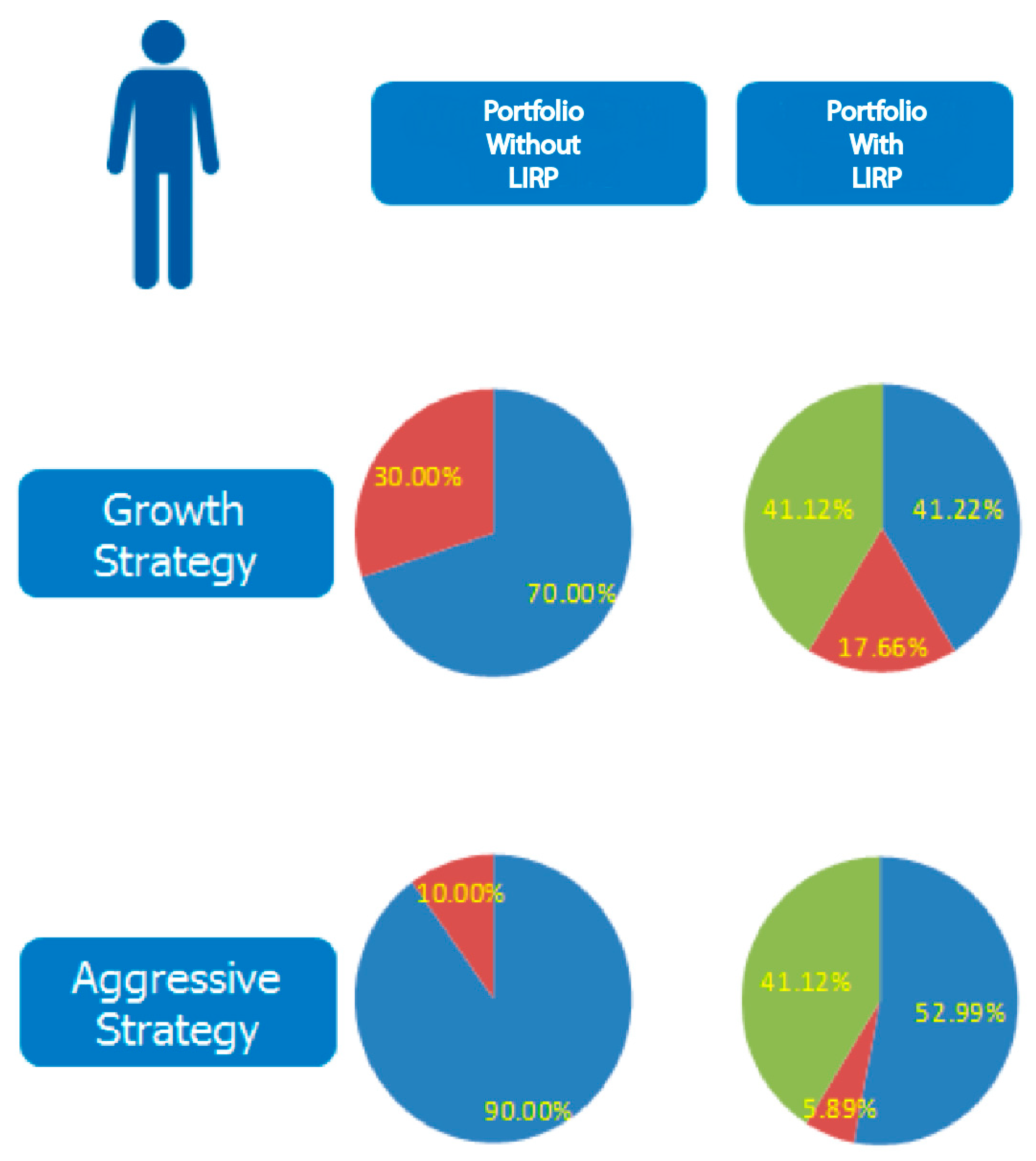

In this paper, we examine the potential of life insurance to meet both income and bequest needs in retirement. In particular, we examine the effectiveness of Life Insurance Retirement Plans (LIRPs) in a retirement portfolio.

LIRPs and Other Retirement Savings Vehicles

In the United States, there are several different mechanisms through which investors can save for retirement while enjoying certain tax advantages. In this section, we will briefly discuss some of these vehicles, including 401(k) and related plans, Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), and Roth IRAs, and we will contrast them with LIRPs.

A 401(k) plan is a tax-qualified, employer-sponsored DC plan as defined in subsection 401(k) of the United States Internal Revenue Code. Employees contribute a portion of their paycheck to their 401(k) plan. Often, employers provide a proportional match of the employee’s contribution. Often, employees can choose how to invest their retirement funds from among a menu of investment options offered by the employer. The contributions and investment earnings are tax-deferred; investors do not incur income tax liability until they begin withdrawing funds in retirement, presumably when they are in a lower tax bracket. Nonprofit and governmental employers may offer 403(b) and 457(b) plans, respectively, which share many of the features of 401(k) plans.

An IRA is a self-directed, not an employer-sponsored, retirement savings plan. Contributions to an IRA are tax-deductible, and the investment earnings are tax-deferred. As with a 401(k) plan, individuals only pay taxes when they withdraw the funds at retirement. A Roth IRA is also a self-directed retirement savings plan. Unlike traditional IRAs, contributions are taxable as income; however, the investment earnings and withdrawals are tax-free—not tax-deferred—subject to certain conditions.

The 401(k) plans, IRAs, and Roth IRAs are subject to various income and contribution limits and early withdrawal penalties. A concise overview of traditional and Roth IRAs is given in

Spors (

2018). We refer the reader to

McGill et al. (

2010) and

Allen et al. (

2014) for more detailed information.

Under a LIRP, investors contribute premiums to fund a cash value life insurance policy. Generally speaking, the strategy is to overfund the policy, that is, to pay a large amount of premium for a low face-amount policy. Careful planning is important. If the policy is too overfunded, it will be classified as a Modified Endowment Contract, or MEC, instead of as life insurance for the purposes of taxation. Policyholders can meet their income needs via withdrawals and policy loans. Contributions are not tax-deductible; however, the cash value accumulation is tax-deferred, and withdrawals are tax-free. Moreover, beneficiaries receive a tax-free death benefit upon the death of the policyholder. Thus, a properly structured LIRP (one that is not classified as a MEC) offers tax-deferred cash value accumulation, tax-free withdrawals, and a tax-free death benefit to beneficiaries. In other words, LIRPs share many of the tax advantages of a Roth IRA. More significantly, the limits on income, contributions, and withdrawals are considerably less restrictive than for Roth IRAs (again, subject to MEC limits).

Opinions are mixed about the effectiveness of LIRPs.

Ikokwu (

2013) enthusiastically recommends LIRPs, describing them as a “turbo charged Roth IRA without the limitations.”

McKnight (

2012) points out that if a LIRP is properly structured, the cost can be lower than the annual expenses in a typical 401(k). Moreover, LIRPs can insulate investors from rising tax rates, and some insurance companies allow policyholders to access death benefit proceeds to pay for long-term care.

Bloink and Byrnes (

2011) are more skeptical. They point out that if investors are not savvy, the policy could become classified as a MEC, which would eliminate the tax advantages on policy loans. Moreover, if the policy lapses with outstanding loans, the amount of the loan is taxable. In addition, they point to surrender fees, the cost of insurance, and other charges. They conclude LIRPs offer the greatest benefit and fewer drawbacks for high-net-worth investors who have already maximized other tax-advantaged retirement savings plans.

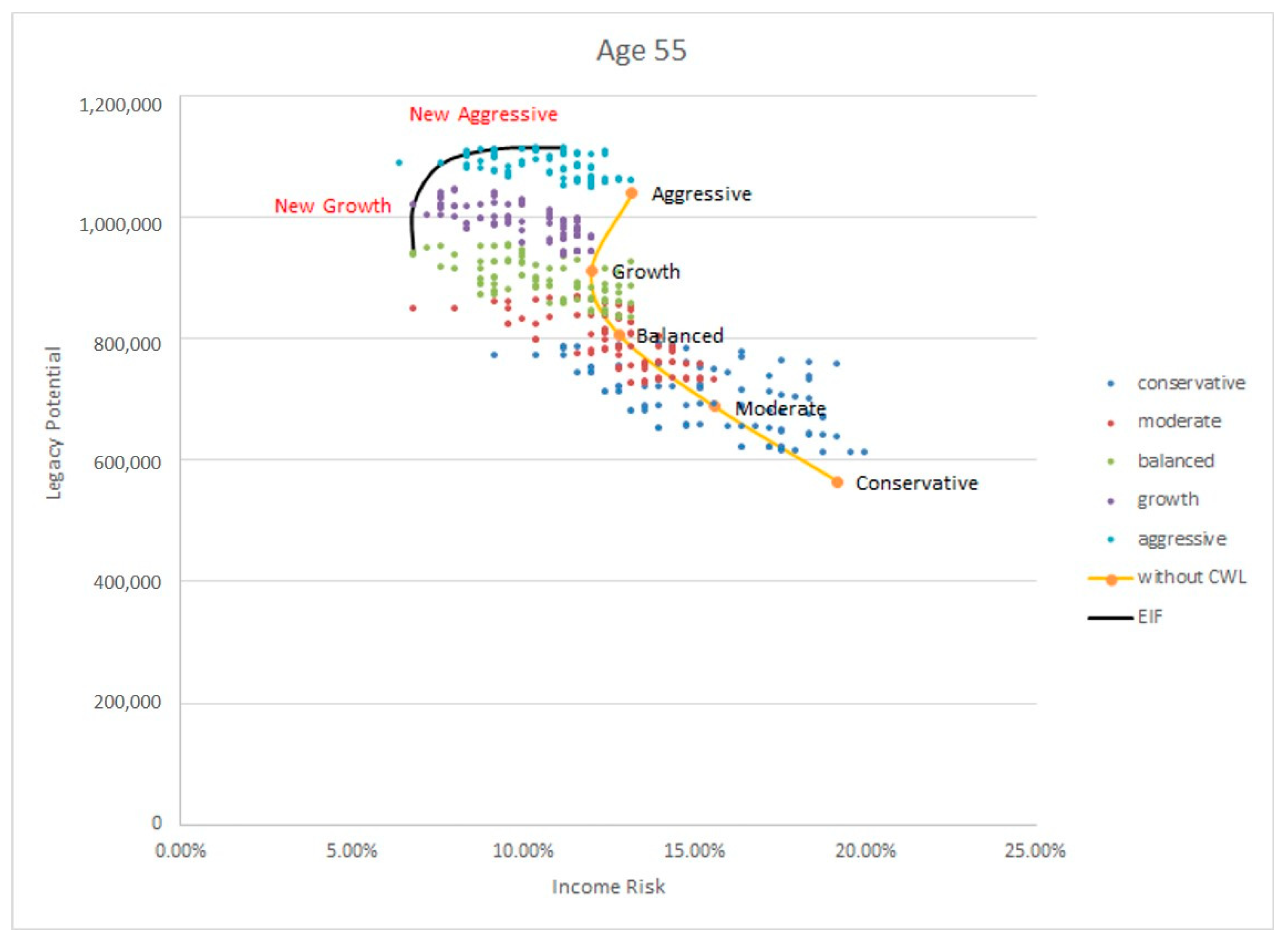

In this paper, we contrast retirement portfolios that include a LIRP with those that include only investment products with no life insurance. In other words, we contrast strategies that include, say, a mutual fund only with those that include both a mutual fund and a LIRP. We consider different issue ages, face amounts, and withdrawal patterns. We simulate market scenarios and, using the Efficient Income Frontier (EIF) of

Milevsky (

2008) and

Pfau (

2013), we demonstrate that portfolios that include LIRPs yield higher legacy potential and smaller income risk than those that exclude it. Thus, we conclude that the inclusion of a LIRP can improve financial outcomes in retirement.