Metallic Material Evaluation of Liquid Hydrogen Storage Tank for Marine Application Using a Tensile Cryostat for 20 K and Electrochemical Cell

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Preparation

2.1. Materials and Specimen

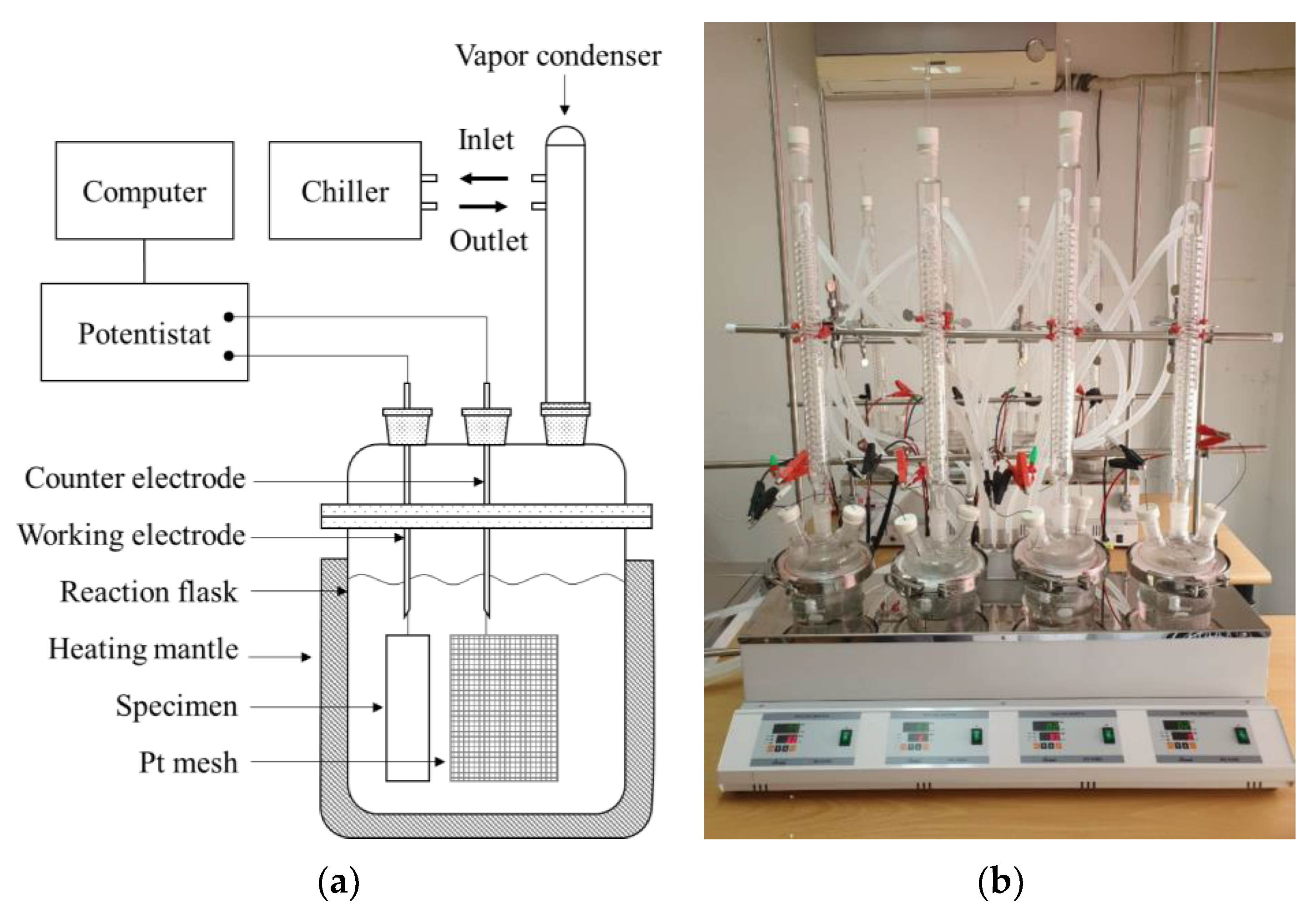

2.2. Hydrogen Charging

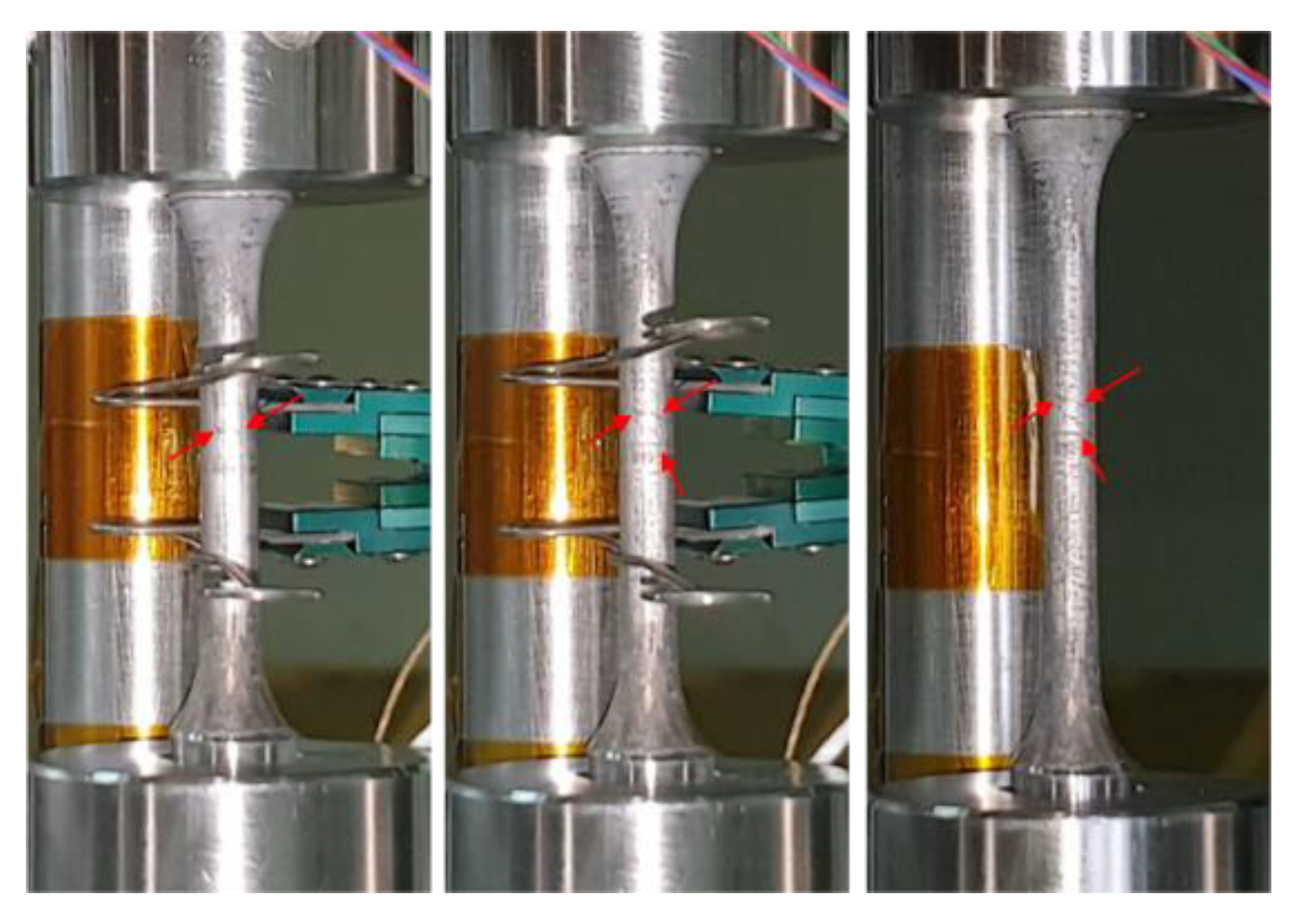

2.3. Apparatus for Cryogenic Tensile Test

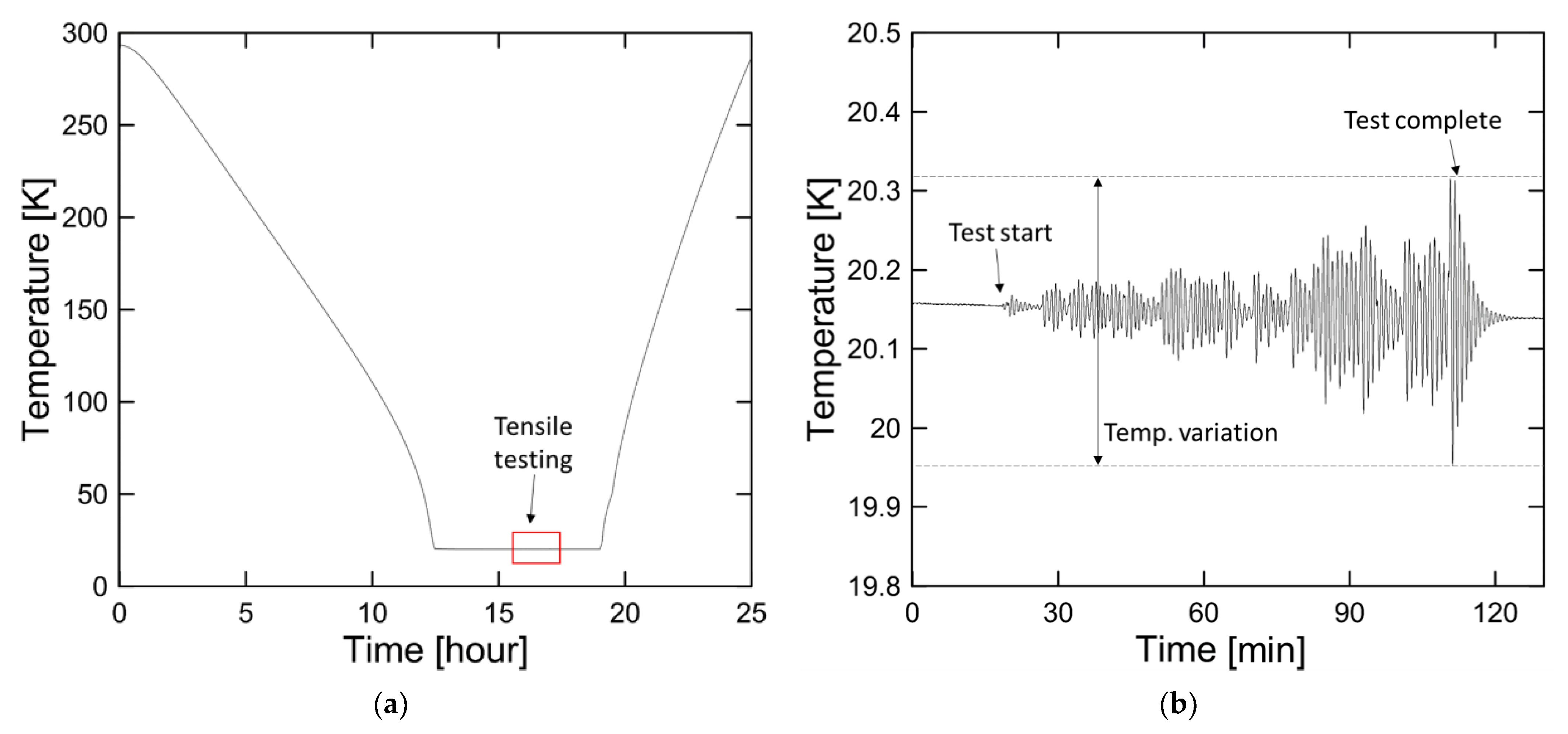

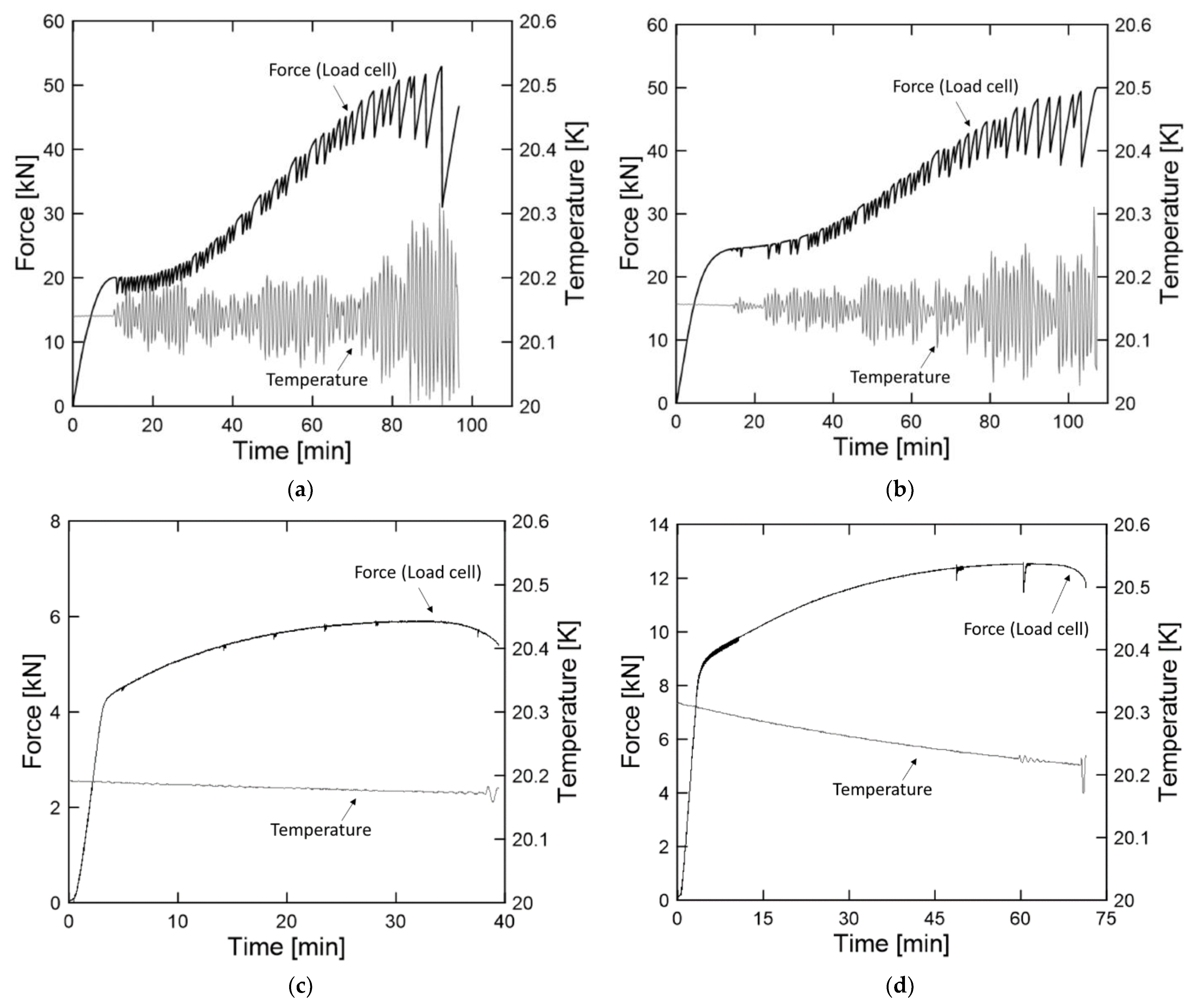

2.4. Test Procedure

3. Results and Discussion

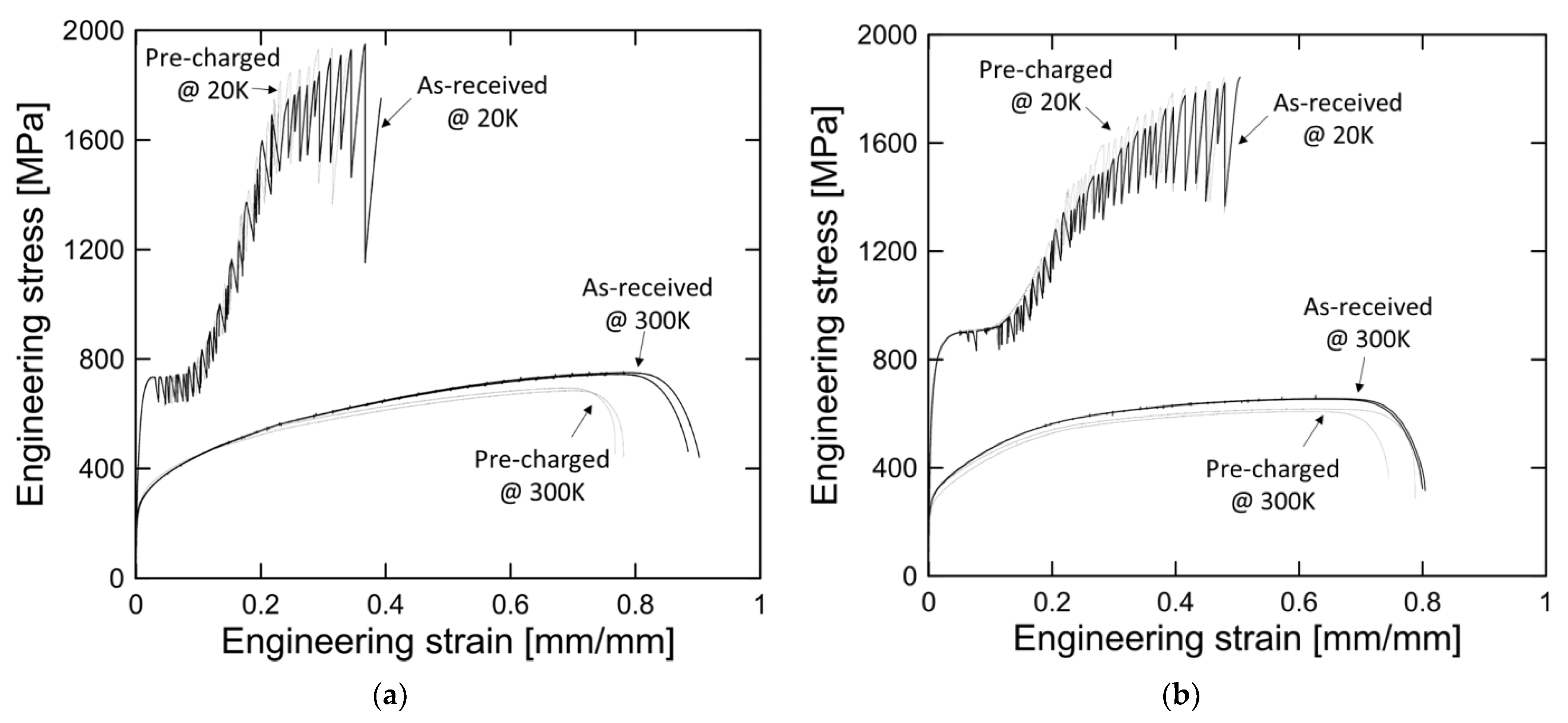

3.1. Effect of Low Temperature

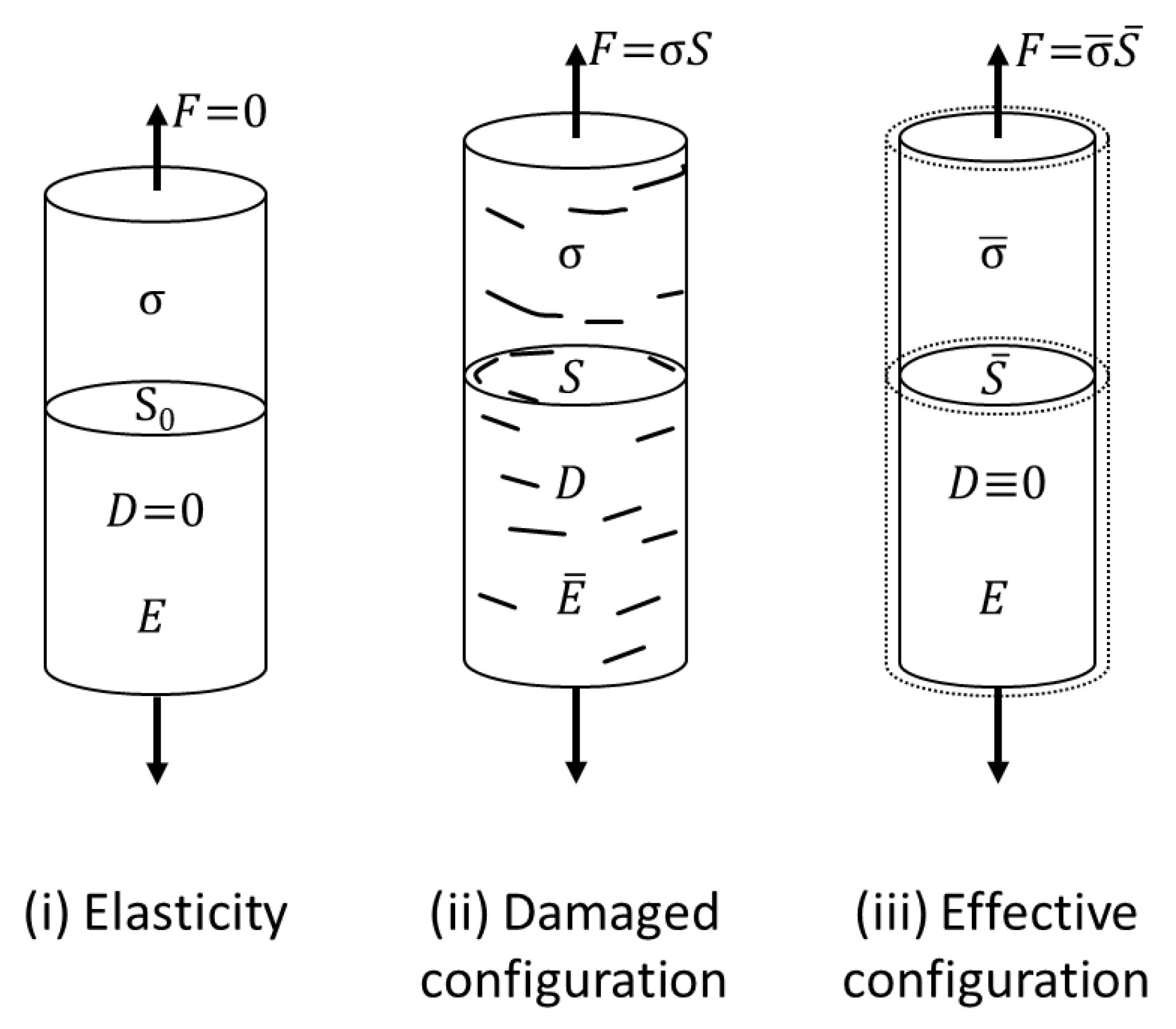

3.2. Effect of Hydrogen Embrittlement

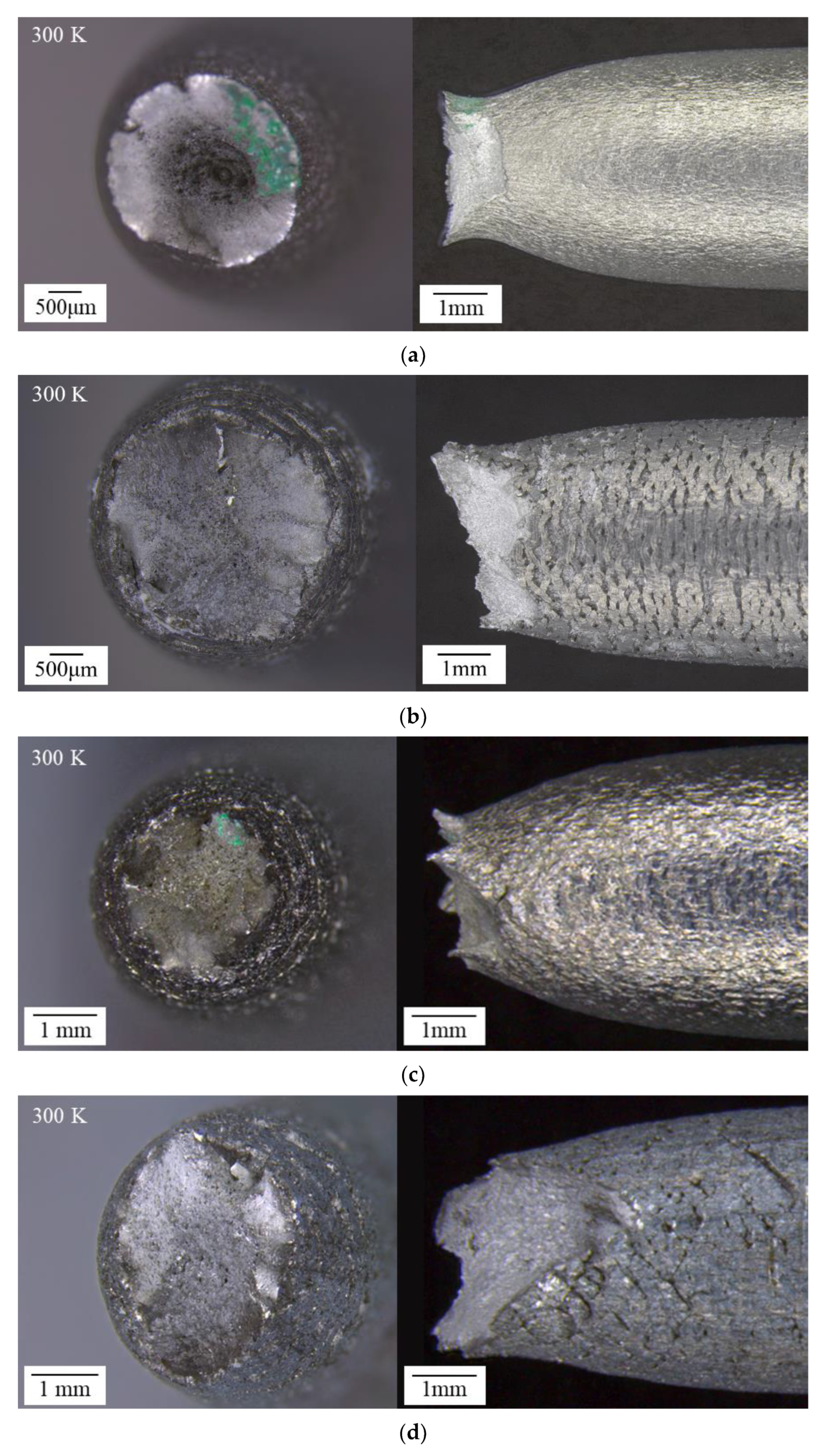

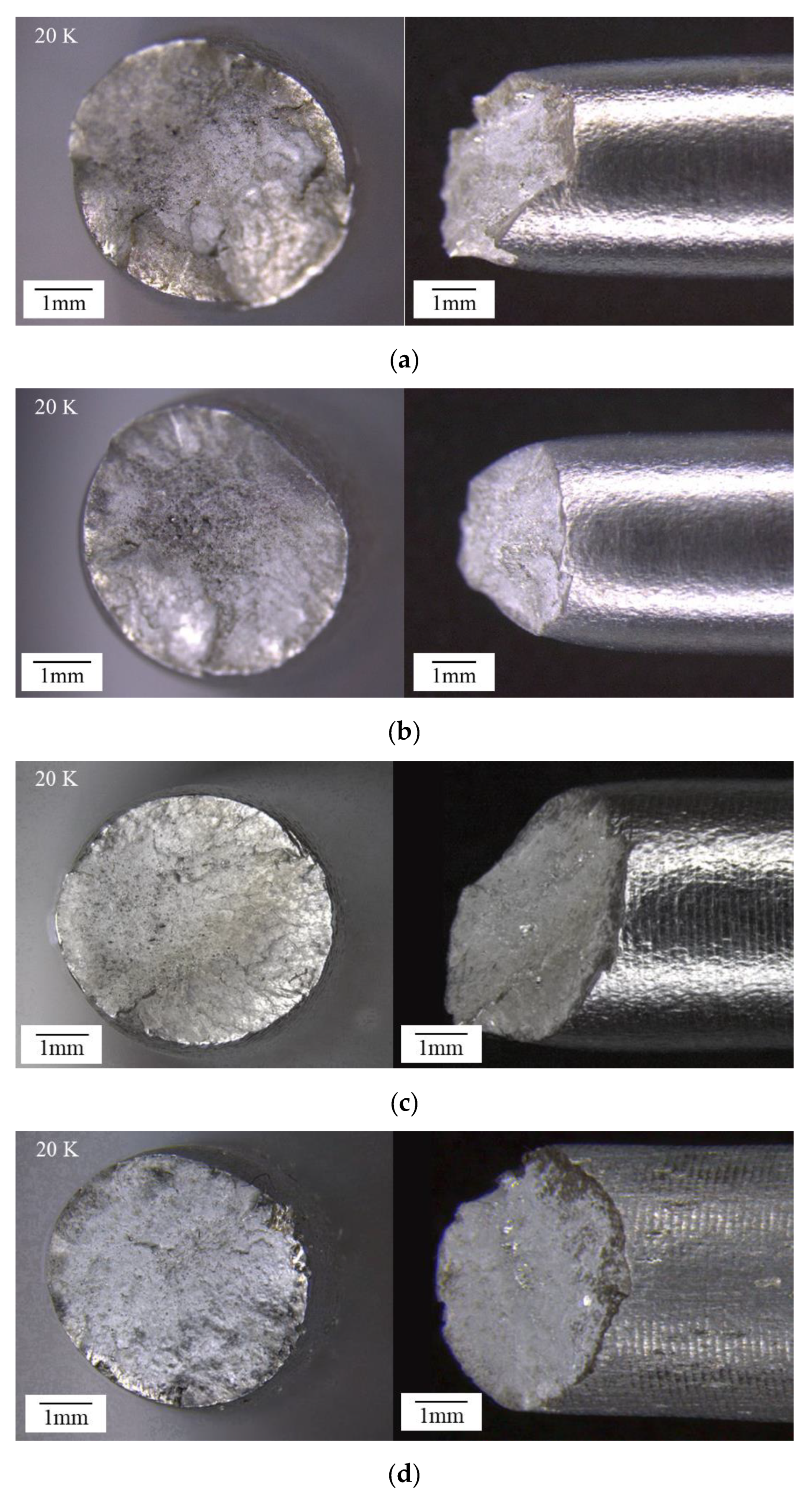

3.3. Macroscopic Analysis

4. Conclusions

- -

- Cathodic charging with high current density at high temperature (80 °C) resulted in intensive hydrogen concentration on the surface of tensile specimen owing to the low diffusion properties of 304L and 316L stainless steel. A high concentration on the surface caused hydrogen-induced cracking on the surface of the tensile specimen, which is the same as the effect of reducing the load-carrying area; it is considered to decrease tensile strength.

- -

- The tensile hydrogen-pre-charged specimen did not show any significant change in the yield strength and flow stress of the hydrogen-charged specimen up to 20% engineering strain. After 20% plastic deformation of stainless steel, hydrogen pre-charging affected strain-hardening behaviors, such as a decrease in tensile strength and elongation.

- -

- Discontinuous yielding of austenitic stainless steel was observed at 20 K. This phenomenon was accompanied by multiple onset of localized necking and temperature rise. The increase in the yield strength of the hydrogen-pre-charged specimens at 20 K is attributed to hydrogen-induced martensite formation.

- -

- The mechanical performance of the aluminum alloys improved at 20 K in terms of strength and elongation. However, serrated yielding and temperature rise were not observed for the aluminum alloys.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D’Amore-Domenech, R.; Leo, T.J.; Pollet, B.G. Bulk Power Transmission at Sea: Life Cycle Cost Comparison of Electricity and Hydrogen as Energy Vectors. Appl. Energy 2021, 288, 116625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustolin, F.; Campari, A.; Taccani, R. An Extensive Review of Liquid Hydrogen in Transportation with Focus on the Maritime Sector. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Sharp, P.; Brandon, N.; Kucernak, A. System-Level Comparison of Ammonia, Compressed and Liquid Hydrogen as Fuels for Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cell Powered Shipping. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 47, 8565–8584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atilhan, S.; Park, S.; El-Halwagi, M.M.; Atilhan, M.; Moore, M.; Nielsen, R.B. Green Hydrogen as an Alternative Fuel for the Shipping Industry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2021, 31, 100668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivard, E.; Trudeau, M.; Zaghib, K. Hydrogen Storage for Mobility: A Review. Materials 2019, 12, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M. Liquid Hydrogen: A Review on Liquefaction, Storage, Transportation, and Safety. Energies 2021, 14, 5917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berstad, D.; Gardarsdottir, S.; Roussanaly, S.; Voldsund, M.; Ishimoto, Y.; Nekså, P. Liquid Hydrogen as Prospective Energy Carrier: A Brief Review and Discussion of Underlying Assumptions Applied in Value Chain Analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 154, 111772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthelemy, H.; Weber, M.; Barbier, F. Hydrogen Storage: Recent Improvements and Industrial Perspectives. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 7254–7262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagumo, M. Fundamentals of Hydrogen Embrittlement; Springer: Singapore, 2016; ISBN 978-981-10-0160-4. [Google Scholar]

- Venezuela, J.; Gray, E.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Tapia-Bastidas, C.; Zhang, M.; Atrens, A. Equivalent Hydrogen Fugacity during Electrochemical Charging of Some Martensitic Advanced High-Strength Steels. Corros. Sci. 2017, 127, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, I.M.; Pressouyre, G.M. Role of Traps in the Microstructural Control of Hydrogen Embrittlement of Steels; Noyes Publ: Park Ridge, NJ, USA, 1985; ISBN 9780815510277. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Chu, W.Y.; Gao, K.W.; Qiao, L.J. Study of Correlation between Hydrogen-Induced Stress and Hydrogen Embrittlement. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2003, 347, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Lee, J.; Park, H.; Yoo, J.; Chung, S.; Park, J.; Kang, N. Cold Cracks in Fillet Weldments of 600 MPa Tensile Strength Low Carbon Steel and Microstructural Effects on Hydrogen Embrittlement Sensitivity and Hydrogen Diffusion. Korean J. Met. Mater. 2021, 59, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Yang, H.; Tong, L.; Wang, L. Research Progress of Cryogenic Materials for Storage and Transportation of Liquid Hydrogen. Metals 2021, 11, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamabe, J.; Matsuoka, S. Hydrogen Safety Fundamentals. In Hydrogen Energy Engineering; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2016; pp. 359–384. [Google Scholar]

- AIAA. Guide to Safety of Hydrogen and Hydrogen Systems (ANSI/AIAA G-095A-2017); American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Inc.: Reston, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Merkel, D.R.; Nickerson, E.K.; Seffens, R.J.; Simmons, K.L.; San Marchi, C.; Kagay, B.J.; Ronevich, J.A. Effect of Hydrogen on Tensile Properties of 304L Stainless Steel at Cryogenic Temperatures. In Pressure Vessels and Piping Conference; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Deimel, P.; Sattler, E. Austenitic Steels of Different Composition in Liquid and Gaseous Hydrogen. Corros. Sci. 2008, 50, 1598–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CGA H-3; Standard for Cryogenic Hydrogen Storage. Compressed Gas Association: McLean, VA, USA, 2019; pp. 1–26.

- Kim, J.; Park, H.; Jung, W.; Chang, D. Operation Scenario-Based Design Methodology for Large-Scale Storage Systems of Liquid Hydrogen Import Terminal. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 40262–40277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAN Energy Solutions Cryogenic Solutions for Onshore and Offshore Applications. Available online: https://www.man-es.com/docs/default-source/document-sync/man-cryo-eng.pdf?sfvrsn=f1030ce2_2 (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Swanger, A.M.; Notardonato, W.U.; Jumper, K.M. ASME Section VIII Recertification of a 33,000 Gallon Vacuum-Jacketed LH2 Storage Vessel for Densified Hydrogen Testing at NASA Kennedy Space Center. In Pressure Vessels and Piping Conference; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- San Marchi, C.; Michler, T.; Nibur, K.A.; Somerday, B.P. On the Physical Differences between Tensile Testing of Type 304 and 316 Austenitic Stainless Steels with Internal Hydrogen and in External Hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 9736–9745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michler, T.; Naumann, J. Hydrogen Environment Embrittlement of Austenitic Stainless Steels at Low Temperatures. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2008, 33, 2111–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michler, T.; Yukhimchuk, A.A.; Naumann, J. Hydrogen Environment Embrittlement Testing at Low Temperatures and High Pressures. Corros. Sci. 2008, 50, 3519–3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, K.; Minami, T.; Anraku, T.; Iwase, A.; Inoue, H. Effect of Hydrogen Partial Pressure on the Hydrogen Embrittlement Susceptibility of Type304 Stainless Steel in High-Pressure H2/Ar Mixed Gas. ISIJ Int. 2015, 55, 2477–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michler, T.; Elsässer, C.; Wackermann, K.; Schweizer, F. Effect of Hydrogen in Mixed Gases on the Mechanical Properties of Steels—Theoretical Background and Review of Test Results. Metals 2021, 11, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, T. Simple Mechanical Testing Method to Evaluate Influence of High Pressure Hydrogen Gas. In Pressure Vessels and Piping Conference; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ANSI/CSA CHMC 1-2014; Test Methods For Evaluating Material Compatibility in a Compressed Hydrogen Applications—Metals (R2018). CSA Group: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018.

- San Marchi, C.; Ronevich, J.A.; Sabisch, J.E.C.; Sugar, J.D.; Medlin, D.L.; Somerday, B.P. Effect of Microstructural and Environmental Variables on Ductility of Austenitic Stainless Steels. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 12338–12347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukunaga, A. Differences between Internal and External Hydrogen Effects on Slow Strain Rate Tensile Test of Iron-Based Superalloy A286. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 47, 2723–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Atrens, A.D.; Shi, Z.; Verbeken, K.; Atrens, A. Determination of the Hydrogen Fugacity during Electrolytic Charging of Steel. Corros. Sci. 2014, 87, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliezer, D. Hydrogen Assisted Cracking in Type 304L and 316L Stainless Steel. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Effect of Hydrogen on Behavior of Materials; The Metallurgical Society of AIME: Wilkes-Barre, PA, USA, 1981; pp. 565–574. [Google Scholar]

- Michler, T.; Wackermann, K.; Schweizer, F. Review and Assessment of the Effect of Hydrogen Gas Pressure on the Embrittlement of Steels in Gaseous Hydrogen Environment. Metals 2021, 11, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duportal, M.; Oudriss, A.; Feaugas, X.; Savall, C. On the Estimation of the Diffusion Coefficient and Distribution of Hydrogen in Stainless Steel. Scr. Mater. 2020, 186, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Chen, J.; Ye, D.; Xu, Z.; Ge, J.; Zhou, H. Hydrogen Concentration Distribution in 2.25Cr-1Mo-0.25V Steel under the Electrochemical Hydrogen Charging and Its Influence on the Mechanical Properties. Materials 2020, 13, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mine, Y.; Kimoto, T. Hydrogen Uptake in Austenitic Stainless Steels by Exposure to Gaseous Hydrogen and Its Effect on Tensile Deformation. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 2619–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, T. Hydrogen Environment Embrittlement Evaluation in Fatigue Properties of Stainless Steel SUS304L at Cryogenic Temperatures. In AIP Conference Proceedings; American Institute of Physics: College Park, MD, USA, 2010; pp. 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, D.; Huang, R.; Huang, C.; Liu, H.; Han, Y.; Li, L. Liquid Helium Free Mechanical Property Test System with G-M Cryocoolers. Cryogenics 2017, 85, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Fernandez, N.I.; Soares, G.C.; Smith, J.L.; Seidt, J.D.; Isakov, M.; Gilat, A.; Kuokkala, V.T.; Hokka, M. Adiabatic Heating of Austenitic Stainless Steels at Different Strain Rates. J. Dyn. Behav. Mater. 2019, 5, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, T. Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of Structural Materials at Cryogenic Temperatures and International Standardization for Those Methods. In AIP Conference Proceedings; American Institute of Physics: College Park, MD, USA, 2014; pp. 320–326. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM E1450; Standard Test Method for Tension Testing of Structural Alloys in Liquid Helium. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- Lee, J.A. Hydrogen Embrittlement (NASA/TM-2016–218602); National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Huntsville, AL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Larbalestier, D.C.; King, H.W. Austenitic Stainless Steels at Cryogenic Temperatures 1—Structural Stability and Magnetic Properties. Cryogenics 1973, 13, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobba, M.; Mishra, R.K.; Niewczas, M. Flow Stress and Work-Hardening Behaviour of Al–Mg Binary Alloys. Int. J. Plast. 2015, 65, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fan, X.; Chen, X.; Yuan, S. Forming Limit of 6061 Aluminum Alloy Tube at Cryogenic Temperatures. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 306, 117649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wu, Z.; Huang, R.; Wang, W.; Li, L. Mechanical Properties of AA5083 in Different Tempers at Low Temperatures. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 279, 12002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschamps, A.; Niewczas, M.; Bley, F.; Brechet, Y.; Embury, J.D.; Sinq, L.L.; Livet, F.; Simon, J.P. Low-Temperature Dynamic Precipitation in a Supersaturated AI-Zn-Mg Alloy and Related Strain Hardening. Philos. Mag. A 1999, 79, 2485–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, B.; Weißensteiner, I.; Kremmer, T.; Grabner, F.; Falkinger, G.; Schökel, A.; Spieckermann, F.; Schäublin, R.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Pogatscher, S. Mechanism of Low Temperature Deformation in Aluminium Alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 795, 139935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.-Y.; Niewczas, M. Plastic Deformation of Al and AA5754 between 4.2K and 295K. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 491, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obst, B.; Nyilas, A. Time-Resolved Flow Stress Behavior of Structural Materials at Low Temperatures. In Advances in Cryogenic Engineering Materials; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 331–338. [Google Scholar]

- Obst, B.; Nyilas, A. Experimental Evidence on the Dislocation Mechanism of Serrated Yielding in f.c.c. Metals and Alloys at Low Temperatures. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1991, 137, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabin, J.; Skoczen, B.; Bielski, J. Strain Localization during Discontinuous Plastic Flow at Extremely Low Temperatures. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2016, 97–98, 593–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pustovalov, V.V. Serrated Deformation of Metals and Alloys at Low Temperatures (Review). Low Temp. Phys. 2008, 34, 683–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, R.P.; Walsh, R.P. Tensile Strain Rate Effects in Liquid Helium. Adv. Cryog. Eng. 1988, 34, 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Radebaugh, R. Cryogenic Measurements. In Handbook of Measurement in Science and Engineering; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 2181–2224. [Google Scholar]

- Duthil, P. Material Properties at Low Temperature. CAS-CERN Accelerator School: Superconductivity for Accelerators. Available online: http://cds.cern.ch/record/1973682 (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Marquardt, E.D.; Le, J.P.; Radebaugh, R. Cryogenic Material Properties Database. In Cryocoolers 11; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 681–687. [Google Scholar]

- Mine, Y.; Horita, Z.; Murakami, Y. Effect of Hydrogen on Martensite Formation in Austenitic Stainless Steels in High-Pressure Torsion. Acta Mater. 2009, 57, 2993–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Y.; Okazaki, S.; Takakuwa, O.; Matsunaga, H. The Roles of Internal and External Hydrogen in the Deformation and Fracture Processes at the Fatigue Crack Tip Zone of Metastable Austenitic Stainless Steels. Scr. Mater. 2018, 157, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, S.; Abro, M.; Lee, D. Effect of Hydrogen and Strain-Induced Martensite on Mechanical Properties of AISI 304 Stainless Steel. Metals 2016, 6, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, M.; Terao, N.; Tsuzaki, K. Revisiting the Effects of Hydrogen on Deformation-Induced γ-ε Martensitic Transformation. Mater. Lett. 2019, 249, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanino, M.; Komatsu, H.; Funaki, S. Hydrogen Induced Martensitic Transformation and Twin Formation in Stainless Steels. J. Phys. Colloq. 1982, 43, C4-503–C4-508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, B.H.; Lee, S.W.; Ahn, J.K.; Lee, J.; Lim, T.W. Hydrogen Induced Cracks in Stainless Steel 304 in Hydrogen Pressure and Stress Corrosive Atmosphere. Korean J. Met. Mater. 2020, 58, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Song, Y.; Shi, Q.; Hu, S.; Zheng, J.; Xu, P.; Zhang, L. Effect of Pre-Strain on Hydrogen Embrittlement of Metastable Austenitic Stainless Steel under Different Hydrogen Conditions. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2019, 44, 26036–26048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Gong, J.; Shen, L.; Dong, W. Hydrogen Embrittlement of Catholically Hydrogen-Precharged 304L Austenitic Stainless Steel: Effect of Plastic Pre-Strain. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 13909–13918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachanov, L.M. Time of the Rupture Process under Creep Conditions. Izv. Akad. Nauk. SSR Otd. Tekh. 1958, 8, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre, J. A Continuous Damage Mechanics Model for Ductile Fracture. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. Trans. ASME 1985, 107, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gong, J.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Jiang, W. Ductility Loss of Hydrogen-Charged and Releasing 304L Steel. Front. Mech. Eng. 2013, 8, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Chemical Composition (%) | ||||||||||||

| Si | Fe | Cu | Mn | Mg | Cr | Zn | Ti | Others | Al | - | - | ||

| Al alloy | 5083-H112 | 0.108 | 0.262 | 0.026 | 0.501 | 4.372 | 0.138 | 0.032 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 94.39 | - | - |

| 6061-T6 | 0.692 | 0.456 | 0.275 | 0.069 | 1.108 | 0.187 | 0.011 | 0.03 | 0.052 | 97.12 | - | - | |

| Type | Chemical composition (%) | ||||||||||||

| C | Si | Mn | P | S | Cr | Ni | Mo | N | Co | Cu | Fe | ||

| Stainless steel | 304L | 0.025 | 0.4 | 1.64 | 0.033 | 0.002 | 18.14 | 8.07 | 0.11 | 0.073 | 0.22 | 0.22 | bal. |

| 316L | 0.019 | 0.47 | 1.25 | 0.03 | 0.002 | 16.64 | 10.1 | 2.1 | 0.07 | 0.2 | 0.26 | bal. | |

| Specimen Type | Hydrogen Content (wppm) | |

|---|---|---|

| 304L stainless steel | As-received | 3 |

| Pre-charged | 12 | |

| 316L stainless steel | As-received | 4 |

| Pre-charged | 13 | |

| Material | Temp. (K) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation(%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. | Std. | Avg. | Std. | Avg. | Std. | ||

| STS 304L | 300 | 299.0 | 2.6 | 765.3 | 11.8 | 86.2 | 3.8 |

| 20 | 682.0 | 7.1 | 1943 | 9.9 | 39.0 | 1.1 | |

| STS 316L | 300 | 313.5 | 2.1 | 660.5 | 7.8 | 80.0 | 0.3 |

| 20 | 777.0 | 18.4 | 1824 | 9.5 | 50.4 | 0.0 | |

| Al 5083-H112 | 300 | 294.0 | 2.8 | 313.5 | 2.1 | 22.6 | 0.3 |

| 20 | 353.5 | 0.7 | 470.5 | 0.7 | 26.7 | 2.3 | |

| Al 6061-T6 | 300 | 269.5 | 3.5 | 291.0 | 1.4 | 27.1 | 0.0 |

| 20 | 331.0 | 1.4 | 461.0 | 1.4 | 36.6 | 0.3 | |

| Material | H2 Charging | Testing Temp. (K) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. | Std. | Ratio (%) | Avg. | Std. | Ratio (%) | Avg. | Std. | Ratio (%) | |||

| STS 304L | AR | 300 | 299 | 2.6 | 99.7 | 765 | 11.8 | 89.1 | 86.2 | 3.8 | 89.5 |

| PC | 300 | 298 | 11.3 | 682 | 3.5 | 77.1 | 0.9 | ||||

| AR | 20 | 682 | 7.1 | 97.4 | 1943 | 9.9 | 97.4 | 39.0 | 1.1 | 89.6 | |

| PC | 20 | 664 | 26.9 | 1893 | 31.1 | 34.9 | 2.8 | ||||

| STS 316L | AR | 300 | 313 | 2.1 | 95.8 | 661 | 7.8 | 93.3 | 80.0 | 0.3 | 95.5 |

| PC | 300 | 300 | 19.8 | 616 | 8.5 | 76.4 | 3.1 | ||||

| AR | 20 | 777 | 18.4 | 98.8 | 1824 | 9.5 | 97.6 | 50.4 | 0.0 | 103 | |

| PC | 20 | 768 | 8.5 | 1780 | 68.6 | 51.9 | 2.6 | ||||

| Material | Testing Temp. (K) | Hydrogen Charging | Reduction in Area (%) | Relative RA (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. | Std. | Avg. | |||

| STS 304L | 300 | As-received | 78.3 | 0.3 | 84.8 |

| Pre-charged | 66.4 | 1.8 | |||

| 20 | As-received | 47.2 | 1.2 | 89.0 | |

| Pre-charged | 42.0 | 4.6 | |||

| STS 316L | 300 | As-received | 84.5 | 1.7 | 84.6 |

| Pre-charged | 71.4 | 0.9 | |||

| 20 | As-received | 38.6 | 0.5 | 83.8 | |

| Pre-charged | 32.4 | 2.3 | |||

| Al 5083-H112 | 300 | As-received | 53.6 | 1.7 | N.A. |

| 20 | 34.6 | 0.0 | |||

| Al 6061-T6 | 300 | As-received | 43.0 | 1.7 | N.A. |

| 20 | 23.7 | 1.3 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, M.-S.; Lee, T.; Son, Y.; Park, J.; Kim, M.; Eun, H.; Park, J.-W.; Kim, Y. Metallic Material Evaluation of Liquid Hydrogen Storage Tank for Marine Application Using a Tensile Cryostat for 20 K and Electrochemical Cell. Processes 2022, 10, 2401. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10112401

Kim M-S, Lee T, Son Y, Park J, Kim M, Eun H, Park J-W, Kim Y. Metallic Material Evaluation of Liquid Hydrogen Storage Tank for Marine Application Using a Tensile Cryostat for 20 K and Electrochemical Cell. Processes. 2022; 10(11):2401. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10112401

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Myung-Sung, Taehyun Lee, Yeonhong Son, Junesung Park, Minsung Kim, Hyeonjun Eun, Jong-Won Park, and Yongjin Kim. 2022. "Metallic Material Evaluation of Liquid Hydrogen Storage Tank for Marine Application Using a Tensile Cryostat for 20 K and Electrochemical Cell" Processes 10, no. 11: 2401. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10112401

APA StyleKim, M.-S., Lee, T., Son, Y., Park, J., Kim, M., Eun, H., Park, J.-W., & Kim, Y. (2022). Metallic Material Evaluation of Liquid Hydrogen Storage Tank for Marine Application Using a Tensile Cryostat for 20 K and Electrochemical Cell. Processes, 10(11), 2401. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10112401