1. Introduction

With the global objective of achieving Net Zero Emissions by 2050, the semiconductor industry plays a crucial role in addressing climate change. As a leading semiconductor manufacturing company in Singapore, our focus on reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions aligns with the industry’s commitment to sustainable practices. In line with the Scientific Basis-Based Targets (SBTi), many semiconductor fabs in Singapore have set annual carbon emission reduction targets of 3–4% [

1]. To meet these targets, various strategies have been implemented, including the accelerated installation of local scrubbers, the promotion of energy-saving equipment and measures, and the adoption of green electricity equipment. Singapore, as a nation, is actively working towards reducing GHG emissions and has set baseline targets for carbon reduction. In this context, the semiconductor industry in Singapore aims to achieve an emission rate of less than 25,000 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (t/CO

2e) by 2023 [

2], as per the baseline established by the National Environment Agency. To achieve this goal, advanced control technology is being implemented across different phases of semiconductor manufacturing [

2,

3]. The methodology employed for reducing GHG emissions draws inspiration from the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) published methods AM0078 and AM0111 by the Environmental Protection Administration. These methods incorporate the latest abatement and management systems, providing a comprehensive approach to GHG reduction. Additionally, a systematic verification method has been developed to assess the effectiveness of these reduction measures [

4,

5].

The primary objective of this mini-review is to present the implementation principles of optimal control technology for reducing GHG emissions in the semiconductor industry. By leveraging established reduction methods and guidance from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), this review aims to address the lack of clear guidelines for reducing fluorinated compounds (FCs), N

2O, and NF

3 greenhouse gases in the semiconductor industry. Specifically, this review focuses on the installation of efficient exhaust gas destruction equipment for the removal of FCs and N

2O from critical processes such as Etching, ThinFilm (including chemical/physical vapor deposition), and Diffusion [

6,

7]. By analyzing current best practices and considering the unique requirements of the semiconductor industry, this review aims to provide actionable insights and recommendations for the reduction of GHG emissions. The remainder of this mini-review is structured as follows:

Section 2 provides a comprehensive literature review, highlighting the current state of knowledge on GHG reduction in the semiconductor industry.

Section 3 outlines the methodology used in developing the implementation principles for optimal control technology.

Section 4 presents the proposed principles and discusses their applicability to the semiconductor industry in Singapore. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes the key findings, implications, and recommendations for future research and practice. By undertaking this mini-review, we aim to contribute to the advancement of sustainable practices within the semiconductor industry, specifically focusing on the reduction of GHG emissions. Through collaboration and the adoption of innovative solutions, the industry can play a pivotal role in mitigating climate change and ensuring a greener future.

2. Greenhouse Gas Reduction Strategies in the Semiconductor Industry

The semiconductor industry plays a vital role in technological advancements and innovation, but it is also recognized as one of the major contributors to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [

8]. As the urgency to address climate change grows, there is a pressing need to identify and implement effective strategies for reducing GHG emissions in semiconductor manufacturing processes [

9]. This comprehensive literature review aims to provide an overview of the current knowledge and best practices related to GHG reduction in the semiconductor industry, with a specific focus on Singapore [

10]. The current literature review on GHG reduction in the semiconductor industry provides a comprehensive overview of the state of knowledge and best practices in this field. The novelty of this study lies in its specific focus on the semiconductor industry in Singapore, which allows for a detailed examination of the strategies and initiatives implemented in a specific context.

The review also identifies greenhouse gas substitution as a key strategy for reducing net fluorine-gas emissions in the semiconductor industry. The novelty here lies in the evaluation of alternative gases that not only have lower global warming potential (GWP) but also meet the performance and operational requirements of semiconductor manufacturing processes. This assessment considers potential safety and health impacts on fab operations, employee protection, and external environmental impacts.

2.1. Greenhouse Gas Substitution-Phase 1

To further reduce net fluorine-gas emissions in the semiconductor industry, one approach is to replace gases with high global warming potential (GWP) with alternatives that have lower GWP or no GWP. This substitution strategy aims to use gases more efficiently in the plasma process [

11]. The gases of particular concern in this context are CF

4, C

2F

6, C

3F

8, c-C

4F

8, CHF

3, CH

2F

2, CH

3F, NF

3, and SF

6. These gases have significant GWP values and contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. CF

4 is commonly used in both Etching and ThinFilm processes, while CHF

3, CH

2F

2, and C

2F

6 are also used in various semiconductor manufacturing processes [

12,

13].

When considering alternative chemicals for substitution, it is essential to evaluate their potential safety and health impacts on fab operations, employee protection, and external environmental impacts [

8]. The objective is to identify replacement gases that not only offer lower GWP but also maintain the desired performance and operational requirements of the semiconductor manufacturing processes.

Table 1 summarizes the GWP values, by-products, and noteworthy remarks for the relevant gas categories. These values are based on the Carbon Pricing Act 2018 (CPA 2018) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2019 assessment [

1,

2]. It is important to note that CF

4, C

2F

6, and CHF

3 are frequently mentioned due to their significant GWP and their presence as by-products in various semiconductor processes [

14].

Through the Greenhouse Gas Substitution-Phase 1, semiconductor manufacturers can make informed decisions regarding the replacement of high GWP gases with alternatives that have a lower environmental impact. This phase requires careful consideration of the gases’ performance, safety implications, and overall reduction potential in greenhouse gas emissions [

8,

15].

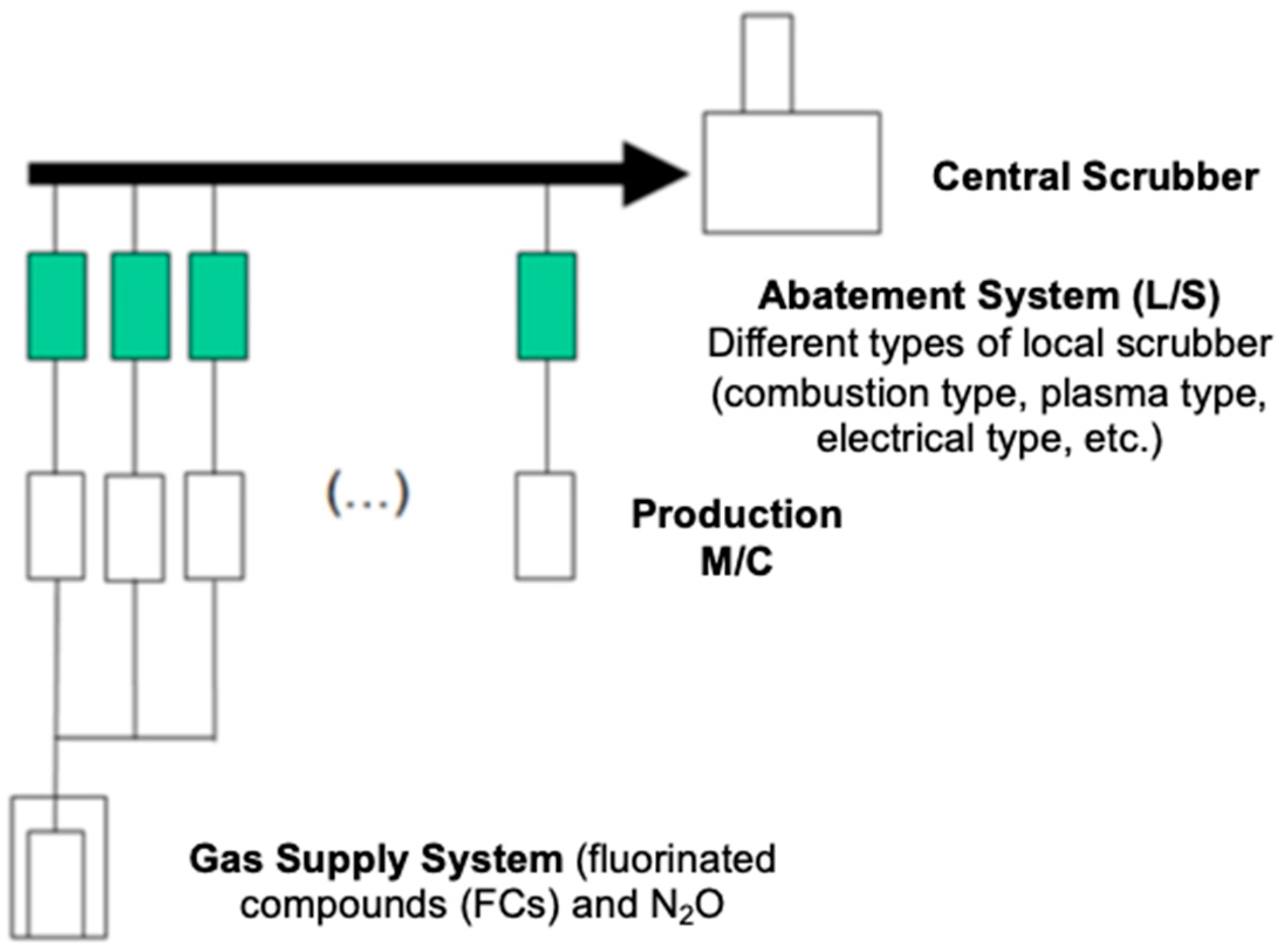

2.2. Advanced Abatement Methodology-Phase 2

The semiconductor industry has developed and commercialized various advanced abatement technologies to reduce fluorine-gas emissions effectively. The focus has been on implementing abatement systems (

Figure 1) near the emission source to prevent further contamination and dilution of the gases [

9,

10].

This approach involves connecting each emission stream to a local scrubber, enabling accurate calculations of FC emissions [

9,

10]. The connection method between the production system and the abatement system is crucial for achieving precise emission measurements. Venting equipment and process conditions, such as the temperature, fluorinated greenhouse gas inlet concentration, flow rate, pump purge rate, and total inlet flow composition, significantly impact the performance of the venting system [

11,

12].

The

Table 2 provides an overview of different advanced abatement methods commonly used in the semiconductor industry. These methods focus on the removal of fluorinated compounds (FCs) and N

2O greenhouse gases from various semiconductor manufacturing processes, including Etching, ThinFilm deposition, and Diffusion processes [

16]. The combustion-based abatement system involves the installation of efficient combustion-based systems that effectively remove FCs and N

2O. Similarly, the electric-based abatement system utilizes electric-based technologies for emission reduction. Plasma-based abatement systems leverage plasma technology to remove FCs and N

2O. Additionally, other methods, such as UV-based systems, may be employed for FC and N

2O abatement. The primary objective of these abatement methods is to reduce the emissions of specific greenhouse gases, including CF

4, C

2F

6, C

3F

8, c-C

4F

8, CHF

3, CH

2F

2, CH

3F, NF

3, and SF

6. By employing these advanced abatement methods, semiconductor manufacturers can effectively mitigate the environmental impact of their operations and contribute to global efforts in reducing GHG emissions.

2.3. Process Optimization-Phase 2 and 3

Process optimization plays a critical role in reducing greenhouse gas consumption and minimizing fluorinated greenhouse gas emissions in semiconductor manufacturing. By modifying process variables such as chamber pressure, temperature, plasma power, cleaning gas flow rate, gas flow time, and gas ratio, it is possible to decrease carbon emissions [

6]. Process improvement techniques, including endpoint inspection systems utilizing mass spectrometry, infrared spectroscopy, optical emission spectroscopy, and radio frequency impedance monitoring, provide valuable data for optimizing processes [

7]. These techniques have been extensively used for cleaning chemical vapor deposition (CVD) chambers, and they can also be applied to Etching and other fluorinated greenhouse gas plasma operations.

2.4. Remote Plasma Cleaning System-Phase 4

Remote plasma cleaning technology has emerged as an alternative to in situ CVD chamber cleaning. In this approach, a plasma generation unit is installed at the front of the CVD chamber, facilitating the cleaning process [

6]. The plasma unit initiates the reaction of NF

3, generating fluorine radicals and ions that chemically react with the deposited material in the processing chamber (

Figure 2) [

13]. The by-products of this reaction, such as SiF4, are then carried away in gaseous form. Remote plasma cleaning systems can be retrofitted into existing processing tools to replace the original chemistry used for fluorine gas cleaning [

14]. Continuous evaluation and sharing of new technologies within the semiconductor industry are essential for further improvement [

15]. It is crucial to follow reliable measurement protocols when measuring emissions or assessing the effectiveness of new technologies [

16].

2.5. Basis of Preparation and Monitoring Plan-Endorsed by ISO14064 and NEA

The basis of preparation (BoP) and monitoring plan (MP) for GHG reduction initiatives in the semiconductor industry are rooted in the “IPCC 2019 Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, Volume 3, Chapter 6” (IPCC GL) and the Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) Global Warming Potential (GWP) values. Estimation methods based on these guidelines provide a framework for calculating emissions, aligning with the objectives and requirements set forth by environmental agencies such as the National Environment Agency (NEA) [

7,

17]. Adherence to the ISO 14064 standard ensures that GHG reduction efforts in the semiconductor industry comply with internationally recognized protocols [

16].

To conclude, this comprehensive literature review has highlighted the current state of knowledge and best practices for GHG reduction in the semiconductor industry. Through greenhouse gas substitution, advanced abatement methodologies, process optimization, and the use of remote plasma cleaning systems, significant progress has been made in reducing emissions of fluorinated compounds and N

2O gases. The basis of preparation and monitoring plans endorsed by ISO 14064 and NEA provide a standardized approach for measuring and managing emissions [

18]. Further research and development efforts are essential to continue advancing GHG reduction strategies in the semiconductor industry, ultimately contributing to global sustainability goals. Moreover, this literature review also contributes to the existing knowledge by providing insights into the specific strategies and initiatives implemented in the semiconductor industry in Singapore. The novelty of the study lies in its focus on greenhouse gas substitution, advanced abatement methodologies, process optimization, remote plasma cleaning systems, and adherence to standardized monitoring protocols.

3. Methodology for Developing Implementation Principles of Optimal Control Technology

3.1. Overview of the Control Technology Methodology

3.1.1. Old Control Technology

Early PFC abatement systems were not effective in destroying CF

4 because of its strong C-F molecular bonds. Burn boxes operating at temperatures of 800 degrees Celsius were only up to 27% effective in destroying PFCs. Many times, the destruction of CHF

3, C

2F

6, and C

3F

8 generated CF

4 from the decomposition of the original gases [

7]. The semiconductor manufacturing emission factors include fluorinated compounds (FCs) that are not destroyed by the emission reduction system; CO

2 generated as a by-product of the reduction of F-GHGs; CO

2 from the combustion of fossil fuels in the emission reduction system; and CO

2 from electricity use during the operation of the emission reduction system. In the monitoring procedure, the gas concentration at the inlet and outlet of the abatement system will be monitored continuously using two FTIR devices, and the gas velocity at the inlet and outlet of the abatement system will be monitored continuously as well [

8,

10,

13].

The monitoring methodology specifies that the mass of each F-GHG entering and leaving the abatement unit, as well as the inlet and outlet flow rates, should be calculated separately and continuously. The relevant parameters required for the calculation of baseline and project emissions shall be monitored continuously [

14]. All measurements shall be carried out using equipment calibrated according to the relevant industry standards.] In addition to following the QA/QC procedures for measuring gas concentrations as described in the baseline chapter and the QA/QC procedures for measuring flows in the US EPA methodology, the project developer should ensure that maintenance and repair procedures follow, at a minimum, the manufacturer’s recommendations or the requirements specified in this methodology throughout the monitoring period. A record of the maintenance requirements for the monitoring and abatement equipment should be submitted to the verifier [

16].

3.1.2. New Reduction Method

The new methodology is not only applicable to the Etching process, the ThinFilm process, which includes chemical/physical vapor deposition, and Diffusion processes but also to the semiconductor process where FCs and N

2O and NF

3 greenhouse gases are emitted directly into the atmosphere and can also be implied such reduction program. Still, post-production plants should have a history of fluorinated and N

2O greenhouse gas use and utilization rates for three consecutive years prior to the start of the project year; post-production new plants should have a history of fluorinated and N

2O greenhouse gas use and utilization rates for two consecutive years prior to the start of the project year of the installation of the proper abatement system [

14,

15,

16]. The maximum processing capacity of the abatement must be greater than the historical data on the flow of FCs, N

2O, and NF

3 greenhouse gases into the abatement (including all other by-products and diluted gases). The reduction project should also assess that the lifespan of the abatement system is greater than the project period, and existing equipment that fails due to its age can no longer be used in the case of this method; the removal of equipment has been a previous project in reduction measures and can no longer apply for this method [

19].

Fluorinated compounds and the N

2O greenhouse gas usage rate must be the amount of gas used (tons of CO

2e) and wafer production area (m

2) for the installation of exhaust gas destruction treatment equipment, and the wafer size is defined according to the financial annual report of wafer move, including 5”, 6”, 8”, 12”, 18” wafers, etc. The various types of GHGs are requested to follow the global warming potential (GWP) gases announced by US EPA [

20].

The comparative table (

Table 3) highlights the key differences between the old control technology and the new reduction method. The old control technology was found to have limited effectiveness in destroying CF

4, a greenhouse gas with strong molecular bonds. The abatement systems operating at high temperatures were only up to 27% effective in destroying fluorinated compounds (FCs). Additionally, the monitoring in the old control technology relied on the gas concentration and velocity measurements at the inlet and outlet of the abatement system. In contrast, the new reduction method is applicable to various processes and direct emissions of FCs, N

2O, and NF

3. It takes into account the complete emission stream through the implementation of a SCADA system, enabling the monitoring of the total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The new reduction method also emphasizes the need for a high destruction removal efficiency (DRE) of the abatement system, with a requirement of over 90% for most types of treatment equipment. Furthermore, the calculation of gas usage rates in the new reduction method considers the amount of gas used and the wafer production area, taking into account different wafer sizes. This approach provides a more comprehensive and accurate assessment of GHG emissions. Additionally, the new reduction method requires the abatement system’s lifespan to be greater than the project period, ensuring long-term effectiveness and sustainability.

It is important to note that the new reduction method complies with international guidelines such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) mandatory reporting rules. This ensures that the methodology aligns with industry standards and best practices for GHG emissions reduction.

3.2. Important Features of the New Reduction Methods

This method is applicable to the integrated circuit (IC) manufacturing industry. Other targets including semiconductor materials (including chemicals), photomasks, design (including Computer-Aided Design (CAD) software), manufacturing processes, packaging, testing, and equipment may not be applicable to this method. The effectiveness of the damage removal rate of the installed abatement system, which is normally the local scrubber connected to the manufacturing modules, must be considered and referred to the IPCC and US EPA Mandatory Reporting Rule [

21]. Moreover, the destruction removal efficiency (DRE) of the treatment equipment should be greater than 90% (combustion, electric, or plasma type). The DRE of the N

2O treatment equipment should be greater than 60%, and the used local scrubbers purchased by external companies should be tested upon completion of installation [

22].

The new methodology is such that a facility SCADA system would be connected to the emission stream where the total amount of GHG would be monitored. The pressure transducer is installed for the whole production and abatement process to clean the emission stream for cleaning chemical vapor deposition module tool chambers. The local scrubbers are used to treat the GHG so that less will be emitted into the atmosphere. The process can be seen in

Figure 3.

3.3. Integration of International Standards and Guidelines

To ensure the development of robust and reliable implementation principles, international standards and guidelines were integrated into the methodology. The principles were aligned with the recommendations of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the guidelines outlined in the 2019 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories [

23].

Additionally, the principles were developed in accordance with the ISO 14064 standard, which provides guidance on the quantification, monitoring, and reporting of GHG emissions. This integration ensures that the implementation principles are in line with internationally recognized standards and facilitate accurate measurement and reporting of GHG reductions.

3.4. Stakeholder Engagement

The development of the implementation principles involved active engagement with key stakeholders in the semiconductor industry, including semiconductor manufacturers, equipment suppliers, industry associations, and regulatory bodies. Consultations, workshops, and expert interviews were conducted to gather insights, feedback, and recommendations from these stakeholders. Stakeholder engagement played a vital role in understanding the practical challenges and opportunities associated with implementing optimal control technology. It also helped in identifying potential barriers to adoption and exploring strategies for overcoming them.

3.5. Development of Implementation Principles

Based on the information gathered through the methodology described above, the implementation principles for optimal control technology were developed. These principles provide guidance on the selection, installation, operation, and monitoring of control technologies to achieve significant reductions in GHG emissions in the semiconductor industry.

The implementation principles address various aspects, including technology selection criteria, performance indicators, monitoring protocols, and best practices for ongoing maintenance and improvement [

24]. They aim to provide a holistic framework that semiconductor manufacturers can follow to effectively implement optimal control technology and drive sustainable GHG reduction in their operations. By employing this comprehensive methodology, the implementation principles for optimal control technology in the semiconductor industry have been developed. These principles serve as a valuable resource for semiconductor manufacturers seeking to enhance their sustainability efforts and contribute to global climate change mitigation.

4. Proposed Principles and Applicability in the Singapore Semiconductor Industry

In this chapter, we further enhance the understanding of the proposed principles for greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction in the semiconductor industry, with a focus on their applicability to the context of Singapore. We also consider important factors related to monitoring, calculation methodology, and implementation considerations for new reduction methods. By incorporating these additional aspects, we aim to provide a comprehensive framework for sustainable semiconductor manufacturing in Singapore.

4.1. Proposed Principles for GHG Reduction

The previously discussed principles for GHG reduction remain relevant, but we now emphasize the implementation of best control technologies for fluorine-gas, PFCs, and HFCs reduction in semiconductor fabs. These technologies have proven effective in reducing emissions and align with the goals set by the World Semiconductor Council (WSC) and the TSIA Semiconductor Fluorine Gas Emission Reduction BAT Implementation Principles. To achieve the desired reduction targets, it is crucial to establish a standard emission rate (NER) and set specific reduction goals. For instance, the WSC expects a 30% reduction in NER, equivalent to a standard emission rate of 0.22 kgCO2e/cm2 by 2020, based on the 2010 total baseline. Furthermore, the TSIA aligns with the WSC resolution and ensures the implementation of reduction techniques in emission reporting and new plants, including those outside the WSC region.

Additionally, the calculation approach for estimating emissions and by-products should follow the “IPCC 2019 Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, Volume 3: Industrial Processes and Product Use: Chapter 6 Electronics Industry Emission, Tier 2c” formula. This formula takes into account parameters such as the number of fluorinated compounds used, emission factors, destruction rates, creation of by-products, and their corresponding global warming potentials.

4.2. Monitoring Plans and Calculation Approach

To facilitate effective monitoring and reporting, a Monitoring Plan (MP) must be prepared and maintained by corporations exceeding the total GHG emission threshold. The MP should include details on the facility’s GHG emission sources and streams, emission quantification methods, quality management procedures, and uncertainty assessment. The NEA’s guidelines and the MP Template provide guidance on the key elements to document in the MP, including site details, metering and analysis, emission streams, summary tables, and quality management frameworks [

24].

The calculation approach should consider the specific parameters outlined in the Tier 2c formula, as detailed in

Table 4. This includes recording data on gas and chemical consumption sourced from facility SCADA systems and wafer move data from modules CIM systems. By accurately measuring and calculating emissions, semiconductor manufacturers can gain insights into their performance and progress towards GHG reduction goals.

4.3. Implementation Considerations for New Reduction Methods

The implementation of new reduction methods requires careful consideration of several factors. For post-production new plants, historical data on fluorinated and N2O usage and utilization rates for two consecutive years should be available before initiating the project. The abatement system’s processing power must exceed past data on the passage of fluorinated compounds and N2O, including by-products and diluted gases. It is essential to ensure that the lifespan of the abatement system exceeds the project duration, and that existing equipment is in good working condition or replaced if necessary. Additionally, equipment that has been previously used in reduction measures should be removed to avoid redundancy and inefficiencies.

4.4. Applicability to the Singapore Semiconductor Industry

The proposed principles for GHG reduction and the considerations outlined above are highly applicable to the semiconductor industry in Singapore. Singapore’s commitment to environmental sustainability, as reflected in the Sustainable Singapore Blueprint and the Green Plan 2030, aligns with these principles. The advanced infrastructure, strong regulatory frameworks, and collaboration between industry stakeholders create a conducive environment for the implementation of optimal control technologies and the adoption of sustainable practices. By embracing these principles and implementing effective reduction methods, the semiconductor industry in Singapore can lead the way in sustainable semiconductor manufacturing, contributing to national and global environmental goals while maintaining competitiveness in the global market [

25].

4.5. Other Consideration Factors for the Implementation of New Reduction Methods

Prior to the start of the project year for the installation of an effective abatement system, post-production new plants shall have a history of fluorinated and N

2O usage and utilization rates for two consecutive years. The abatement’s maximum processing power must exceed past data on the passage of FCs and N

2O into the abatement (including all other by-products and diluted gases). The reduction project must also determine whether the lifespan of the abatement system is longer than the project, whether existing equipment has failed or grown too old to be used, and remove equipment if it has been in a previous reduction measures project [

19].

4.6. Example of Installing Emission Control Technology with High Destruction Efficiency for C2F6

An exemplary case of installing emission control technology with exceptional destruction efficiency for C2F6 can be illustrated using the following data:

FCg,used (Amount of C2F6 used) = 1000 kg.

Dg for abatement control (combustion/electric heating scrubber) = 0.9.

Dg for abatement control (wet scrubber) = 0.

GWP (Global Warming Potential) for C2F6 = 9200.

Applying the emission calculation equation Eg = FCg,used × {(1 − Cg) × [1 − (Ag × Dg)] × GWPg}, we can assess the remarkable impact of implementing emission control technology. With the installation of highly efficient abatement control technology, the total emission of C2F6 is calculated to be 2,539,200 kg CO2e. This impressive achievement signifies a substantial reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, highlighting the effectiveness of the implemented control measures.

In stark contrast, in the absence of abatement control technology, the total emission of C2F6 amounts to a staggering 5,520,000 kg CO2e. This stark contrast emphasizes the significance of installing emission control technology with high destruction efficiency to mitigate environmental impact and significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. By successfully implementing such effective emission control measures, we not only demonstrate a commitment to environmental sustainability but also contribute significantly to the preservation of our planet. The substantial reduction achieved in C2F6 emissions showcases the positive outcomes that can be achieved when advanced control technologies are applied.

This exemplary case serves as a testament to the remarkable potential for environmental conservation through the adoption of cutting-edge emission control technology. By embracing such initiatives, we pave the way for a greener future and inspire others to follow suit in reducing their environmental footprint.

5. Summary of Key Findings, Implications, and Recommendations for Future Research and Practice

5.1. Summary of Key Findings

This study on semiconductor sustainability manufacturing has yielded several key findings that provide insights into the current state and potential pathways for achieving sustainability goals in the industry [

3]. The following are the major findings:

Importance of Optimal Control Technologies: The implementation of optimal control technologies for greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction, particularly targeting fluorine-gas, PFCs, and HFCs, is crucial in achieving significant emission reductions. These technologies have demonstrated their effectiveness in reducing emissions and aligning with industry association goals and regulatory requirements.

Calculation Approach and Monitoring Plans: The adoption of an accurate and standardized calculation approach, such as the IPCC guidelines, ensures consistent and reliable estimation of emissions and by-products. Furthermore, the development and implementation of robust monitoring plans provide a systematic framework for data collection, analysis, and reporting, enabling better tracking of sustainability performance [

5].

Applicability to the Singapore Semiconductor Industry: The proposed principles and methodologies discussed in this study are highly applicable to the semiconductor industry in Singapore. The country’s supportive infrastructure, regulatory frameworks, and commitment to sustainability create a conducive environment for implementing these principles and achieving sustainable manufacturing practices.

5.2. Implications

The findings of this study have several implications for the semiconductor industry and its stakeholders:

Regulatory Compliance: Semiconductor companies in Singapore should prioritize compliance with relevant environmental regulations and standards. By adopting the proposed principles and methodologies, they can demonstrate their commitment to sustainability and align with national and global sustainability initiatives.

Collaboration and Knowledge Sharing: Collaboration within the industry, both within Singapore and globally, is essential for sharing best practices, exchanging knowledge, and driving continuous improvement. Active participation in industry associations, forums, and working groups can foster collaboration and advance sustainable manufacturing practices.

Continuous Improvement and Innovation: The semiconductor industry should strive for continuous improvement and innovation in GHG reduction technologies and practices. This includes exploring emerging technologies, investing in research and development, and promoting a culture of sustainability within organizations.

5.3. Recommendations for Future Research and Practice

Building upon the findings and implications of this study, the following recommendations are put forth for future research and practice:

Longitudinal Studies: Conduct longitudinal studies to monitor the long-term impact of optimal control technologies and sustainable practices on GHG emissions in the semiconductor industry. These studies can provide insights into the effectiveness of the implemented measures and identify areas for further improvement.

Technological Advancements: Encourage research and development efforts focused on developing more efficient and environmentally friendly semiconductor manufacturing processes. This includes exploring alternative materials, optimizing resource utilization, and integrating clean energy sources within fabs.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): Conduct comprehensive life cycle assessments of semiconductor products to evaluate their environmental impact across the entire product life cycle. This holistic approach will facilitate informed decision-making and support the development of sustainable products and processes.

Stakeholder Engagement: Engage stakeholders, including employees, customers, suppliers, and the local community, in sustainability initiatives. Foster transparency, communication, and collaboration to build a shared understanding of sustainability goals and leverage collective efforts for sustainable manufacturing [

25].

Policy Development: Collaborate with policymakers to develop supportive policies and incentives that encourage sustainable manufacturing practices in the semiconductor industry. Policy frameworks should consider the unique challenges and opportunities faced by the industry and provide a conducive environment for sustainable growth.

5.4. Future Trends and Development of the Semiconductor Industry

The semiconductor industry is witnessing a surge in demand due to the increasing popularity of consumer electronics products and the emergence of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, and the Internet of Things. This growth is driven by factors such as rising household incomes, population growth, digitization, and urbanization [

26]. However, the industry may struggle to meet the surging demand sustainably [

27].

To achieve the target of net-zero emissions by 2050, semiconductor manufacturing companies must explore greener alternatives and prioritize the use of renewable energy sources. Embracing sustainable practices and investing in cleaner technologies will be essential to meet the future demands of the industry while minimizing environmental impact. Collaborative efforts between industry players, policymakers, and research institutions can drive the development and adoption of sustainable solutions in the semiconductor sector.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study on semiconductor sustainability manufacturing has provided significant insights into the current state and potential pathways for achieving sustainability goals in the industry. The key findings emphasize the importance of optimal control technologies, calculation methodologies, and monitoring plans for greenhouse gas reduction in semiconductor manufacturing processes. By implementing these findings, the industry can align with industry association goals and regulatory requirements, and contribute to national and global sustainability initiatives. The implications of this study are far-reaching. Semiconductor companies in Singapore should prioritize regulatory compliance and demonstrate their commitment to sustainability. Collaboration and knowledge sharing within the industry, both locally and globally, are crucial for driving continuous improvement and advancing sustainable manufacturing practices. Moreover, fostering a culture of continuous improvement and innovation is vital for the industry to stay at the forefront of GHG reduction technologies and practices.

Based on the findings and implications, several recommendations for future research and practice are proposed. Longitudinal studies can monitor the long-term impact of optimal control technologies and sustainable practices, providing insights into effectiveness and areas for improvement. Research and development efforts should focus on technological advancements, exploring alternative materials, optimizing resource utilization, and integrating clean energy sources. Conducting comprehensive life cycle assessments will support informed decision-making and the development of sustainable products and processes. Stakeholder engagement and policy development are also essential to leverage collective efforts and create a conducive environment for sustainable growth.

Looking ahead, the semiconductor industry faces the challenge of meeting growing demand sustainably while striving for net-zero emissions by 2050. To achieve this, companies must explore greener alternatives and prioritize the use of renewable energy sources. Embracing sustainable practices and investing in cleaner technologies will be crucial in minimizing environmental impact. Collaboration among industry players, policymakers, and research institutions will play a pivotal role in driving the development and adoption of sustainable solutions in the semiconductor sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.H. and S.Z.; methodology, Y.L.; validation, Y.L., S.Z. and H.H.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, H.H.; resources, Y.L. and Y.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, S.Z., H.Y., Y.Q. and H.H.; visualization, S.Z. and H.Y.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Enerstay Sustainability Pte Ltd. (Singapore) Grant Call (Call 1/2022) _GHG (Project ID VS1-001), Singapore.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no Competing Financial or Non-Financial Interests.

References

- Lee, C.H.; Chang, C.C. Carbon tax in Taiwan: A review and assessment. Energy Policy 2018, 117, 474–485. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, B.; Chiang, J.H. Carbon pricing in Taiwan: Current status and future directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 512–519. [Google Scholar]

- National Climate Change Secretariat. Singapore’s Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement. 2019. Available online: https://www.climateaction.gov.sg/docs/default-source/default-document-library/ndc-report-2019.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Tan, S.Y.; Tan, E.K. Carbon pricing in Singapore: A review and assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 910–921. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.C.; Lin, B. Carbon pricing and its impact on the semiconductor industry in Taiwan. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120301. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.K.; Tan, S.Y. Carbon pricing and its impact on the semiconductor industry in Singapore. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 275, 124868. [Google Scholar]

- Tietenberg, T.H. Reflections—Carbon Pricing in Practice. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2013, 7, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, G.E. Designing a carbon tax to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2009, 3, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, L. The Role of Multiple Pollutants and Pollution Intensities in the Policy Reform of Taxes and Standards. B.E. J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2019, 19, 20180186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambec, S.; Cohen, M.A.; Elgie, S.; Lanoie, P. The Porter Hypothesis at 20: Can Environmental Regulation Enhance Innovation and Competitiveness? Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2013, 7, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Taiwan’s Plan to Implement Carbon Tax from 2023 to Reduce Emissions. Taipei Times. 2019. Available online: https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2019/06/12/2003716583 (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Chu, J. Singapore’s Carbon Tax: What It Means for Businesses. Deloitte Insights. 2019. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/sg/en/insights/industry/energy-and-resources/singapore-carbon-tax-business-implications.html (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Lee, J. Singapore’s Carbon Tax: An Overview. Baker McKenzie. 2019. Available online: https://www.bakermckenzie.com/en/insight/publications/2019/01/singapore-carbon-tax-overview (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources. Singapore’s Carbon Pricing Journey. Available online: https://www.mewr.gov.sg/docs/default-source/default-document-library/carbon-pricing-journey.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- National Development Council. Taiwan’s Carbon Pricing Policy. 2019. Available online: https://www.ndc.gov.tw/En/News/Detail/8781 (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- International Energy Agency. Carbon Pricing. 2018. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/carbon-pricing (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Carbon Pricing in Practice. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/environment/indicators-modelling-outlooks/carbon-pricing-in-practice.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Carbon Tax Center. How Carbon Pricing Works. Available online: https://www.carbontax.org/how-carbon-pricing-works/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- World Bank. Carbon Pricing. 2018. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/climatechange/brief/carbon-pricing (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- International Semiconductor Industry Association. Semiconductor Industry Statistics. 2019. Available online: https://www.semiconductors.org/resources/semiconductor-industry-statistics/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Li, S.-N.; Shih, H.-Y.; Wang, K.-S.; Hsieh, K.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Chou, J. Preventive Maintenance Measures for Contamination Control. Solid-State Technol. 2005, 48, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.-N.; Lin, C.-N.; Shih, H.-Y.; Cheng, J.-H.; Hsu, J.-N.; Wang, K.-S. Default values appear to be overestimating F-GHG emissions from fabs. Solid-State Technol. 2004, 47, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.-N.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Shih, H.-Y.; Hong, J.L. Using an Extractive Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectrometer for Improving Cleanroom Air Quality in a Semiconductor Manufacturing Plant. Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. J. 2003, 64, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, B.K.; Park, J.; Seok, H. Carbon-emission and waste reduction of a manufacturing-remanufacturing system using green technology and autonomated inspection. RAIRO-Oper. Res. 2022, 56, 2801–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, B.K.; Yilmaz, I.; Seok, H. A Sustainable Supply Chain Integrated with Autonomated Inspection, Flexible Eco-Production, and Smart Transportation. Processes 2022, 10, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.L.; Tan, K.T.; Li, Y.Z. Implementation Principles of Optimal Control Technology for the Reduction of Greenhouse Gases in Semiconductor Industry. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 394, 01031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.X.; Li, Y.Z. Research on Improving Energy Storage Density and Efficiency of Dielectric Ceramic Ferroelectric Materials Based on BaTiO3 Doping with Multiple Elements. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).