Towards a Dynamic Optimisation of Comminution Circuit Under Geological Uncertainties

Abstract

:1. Introduction

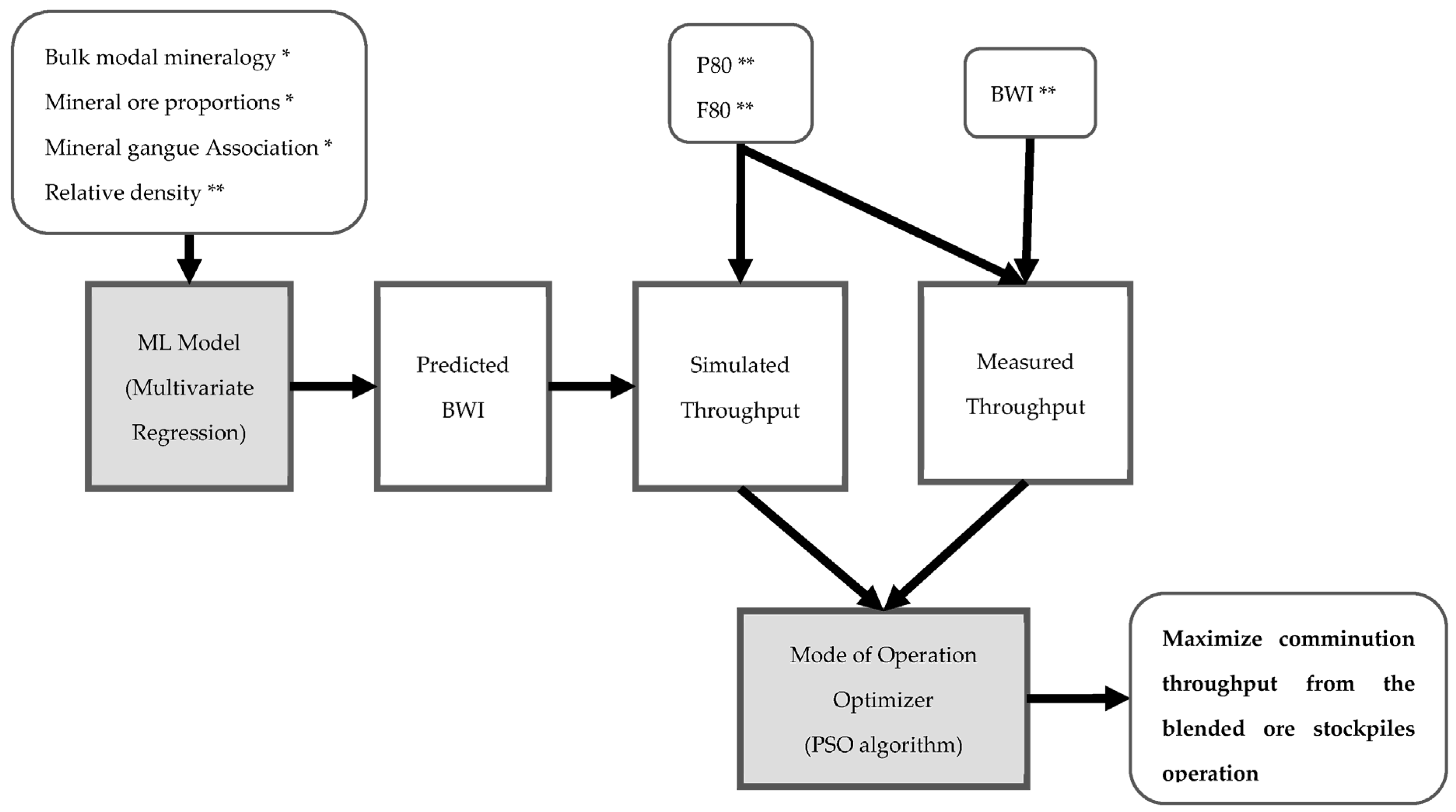

- Identify the key geometallurgical attributes that influence comminution performance in complex PGE ore deposits.

- Develop predictive model for comminution performance based on ore variability.

- Implement a dynamic optimisation algorithm for tactical blending of low-grade and high-grade ore stockpiles.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Complex Orebodies and the PGM Platreef Ore Deposit

2.2. Comminution and Bond Work Index

2.3. Plant Configurations and Operational Challenges

2.4. Machine Learning (ML) in Comminution Performance Prediction

2.5. Optimisation in Stockpile Operational Tactics

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Geometallurgical Data Inputs

3.1.1. Mineralogical Dataset

- Sample preparation: the sample surface was polished to a smooth finish to ensure good electron imaging and accurate X-ray analysis, followed by coating with a thin conductive layer to prevent charging under the electron beam during analysis.

- Instrument setup: measurement parameters were defined, and energy thresholds were set.

- Data acquisition: automatic scanning, mineral identification and mapping were used.

- Data processing and analysis: quantitative analysis of the mineral composition, including modal mineralogy (percentage of different minerals), particle and grain size distribution, mineral associations, liberation characteristics, and textural information, was performed.

3.1.2. Metallurgical Dataset

3.2. Machine Learning Model

3.3. Optimisation of Operational Tactics

| Parameters | Deposits | Mode A | Mode B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | Contingency | Regular | Contingency | ||

| HG FPX (Ore 1) in feed (%) | w1D | w1A | w1ACont | w1B | w1BCont |

| LG P-FPX (Ore 2) in feed (%) | w2D | w2A | w2ACont | w2B | w2BCont |

| Throughput (t/h) | Max rD | rA | rACont | rB | rBCont |

- w1D and w2D are the deposit weight fractions of Ore 1 and Ore 2;

- rA and rB are the feed rates of Mode A and B;

- w1A, w2A, w1B and w2B are the blended feed weight fractions of ores 1 and 2 in Mode A and B, respectively;

- rACont and rBCont are the blended feed rate for the Mode A and B Contingencies;

- w1ACont, w2ACont, w1BCont and w2BCont are the weight fractions of Ore 1 and Ore 2 fed into the Mode A and B Contingencies, respectively.

4. Results

4.1. Key Geometallurgical Attributes Influencing Comminution Performance

4.1.1. Mineralogical Attributes

4.1.2. Metallurgical Attributes

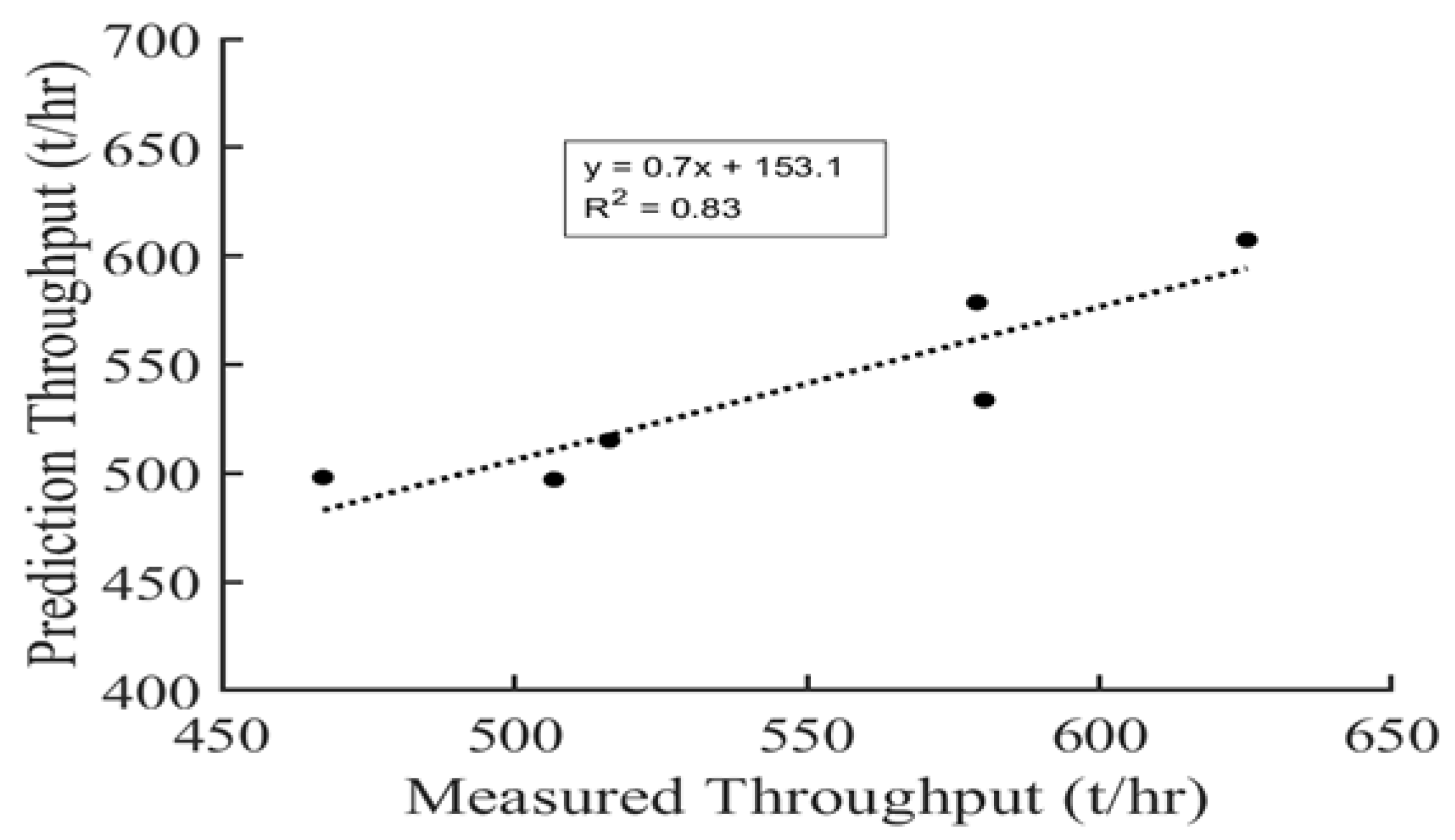

4.2. A Predictive Model for Comminution Performance

| = = Coefficients | = IronOxides*RD |

| = Chlorite | = Silicates*RD |

| = IronOxides | = Chlorite2 |

| = Silicates | = IronOxides2 |

| = RD | = Silicates2 |

| = Chlorite*Silicates | = RD2 |

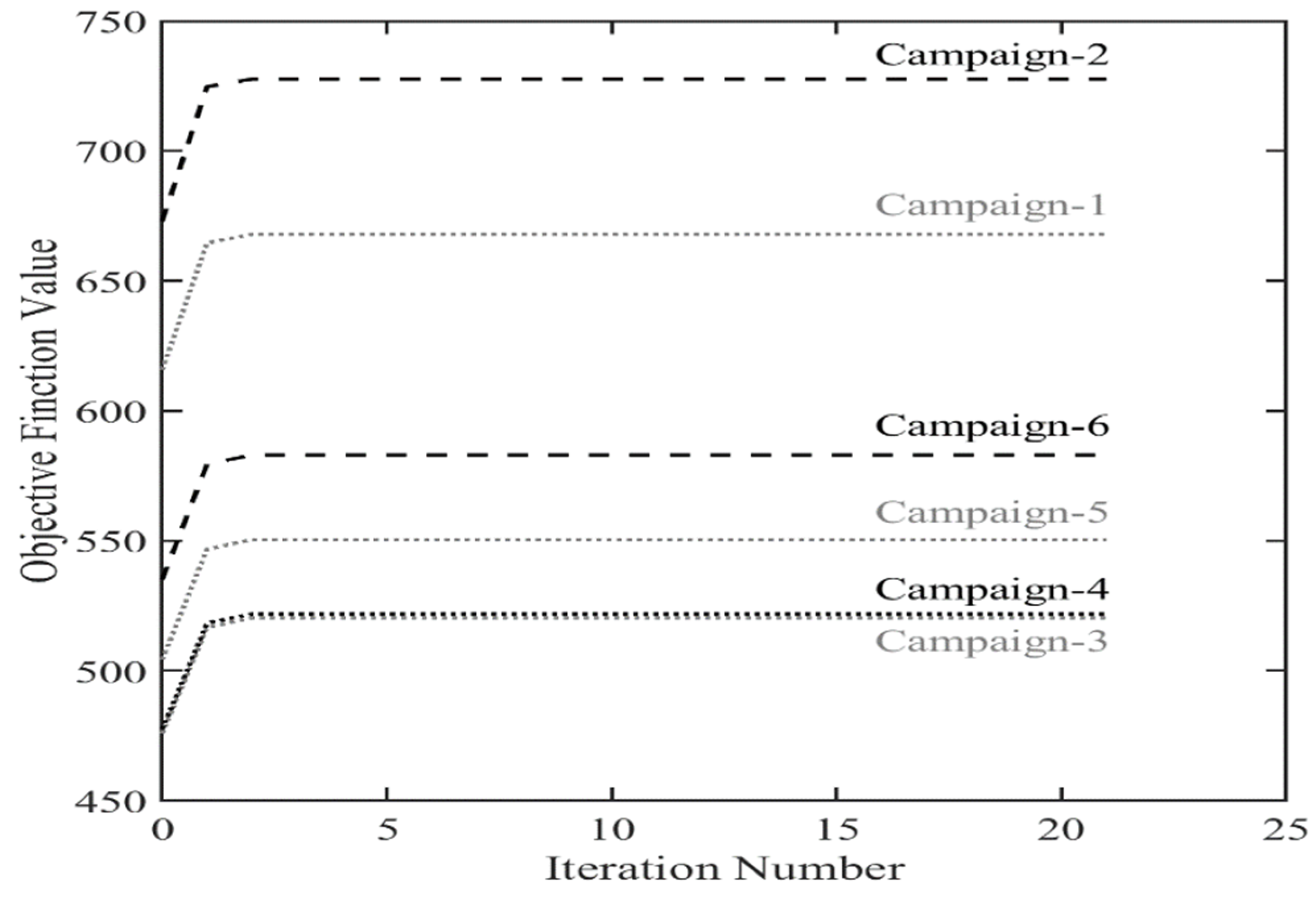

4.3. A Dynamic Optimization Algorithm for Tactical Blending

5. Discussion

5.1. Identification of Key Geometallurgical Attributes Influencing Comminution Performance

5.2. Development of a Predictive Model for Comminution Performance

5.3. Implementation of a Dynamic Optimisation Algorithm for Tactical Blending

6. Conclusions

- The dominance of pyroxene in the FPX and P-FPX samples with lesser amounts of feldspar, other silicates, serpentine and olivine in varying amounts suggests that a multi-objective optimisation-based methodology and statistical modelling can be utilised to address these variations, making it possible to achieve superior performance at Platreef deposit.

- The BMSs in the FPX and P-FPX rock types, dominated by pyrrhotite across all the rock types, with lesser proportions of pentlandite and chalcopyrite with notable variation, highlights that a combination of selective grinding and flotation processes would be the best comminution technique.

- The BMSs in the FPX sample were found to be free from other minerals with a balance associated with main silicates, suggesting that the most suitable comminution technique involves the application of HVP for the selective treatment of mineralised particles. On the other hand, the BMS in the P-FPX sample was found to be free from different minerals, with the balance associated mainly with Chlorite and silicates. This also confirms that a multi-objective approach can be utilised as an optimisation approach when processing such ore.

- Comminution variability tests confirm that the plant feed can be characterised as hard to very hard and thus not suitable for SAG milling. This suggests a processing method that minimises shear forces and fines reduction to prevent unnecessary particle size reduction and energy consumption, as well as control strategies with continuous adjustment and optimisation of crushing parameters.

- The abrasion index and the crusher work index confirm that the ore can be classified as having a medium abrasion tendency, suggesting that employing a vertical roller mill with a horizontal grinding table and the integration of the accelerometer measurements of the mill shell into the control system to optimise the milling process further would be ideal.

- The study demonstrates that a multi-objective technique can be implemented by defining operational tactics between Mode A and Mode B to adapt to variations in mineralogical composition.

- Enhancing the predictive accuracy of the throughput model by incorporating more diverse lithologies and rock types to manage mineralogical variations more effectively.

- Exploring the application of advanced simulation models for ore stockpile management to optimise profit in mining activities, considering the principles of geometallurgy for quantitative forecasts regarding metallurgical efficiency.

- Investigating the economic benefits of employing vertical roller mills with horizontal grinding tables for medium abrasion ores could lead to significant reductions in energy consumption and equipment wear, aligning with the need for efficient ore processing strategies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Mineral | Rock Type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPX1 | FPX2 | FPX3 | FPX4 | |

| BMS | 0.77 | 4.01 | 3.66 | 3.23 |

| Feldspar | 11.74 | 23.34 | 37.96 | 11.22 |

| Clinopyroxene | 13.5 | 17.73 | 16.53 | 23.5 |

| Orthopyroxene | 66.39 | 39.82 | 31.02 | 42.9 |

| Olivine | 0.48 | 1.57 | 0.22 | 0.39 |

| Serpentine | 0.02 | 0.96 | 0.36 | 1.6 |

| Chlorite | 2.13 | 1.14 | 1.14 | 4.99 |

| Other silicates | 4.13 | 9.21 | 8.03 | 9.76 |

| Chromite | 0.18 | 1.02 | 0.3 | 1.5 |

| Fe-Oxides | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.39 | 0.39 |

| Carbonates | 0.13 | 0.7 | 0.37 | 0.49 |

| Other * | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Total | 99.97 | 100 | 99.98 | 99.97 |

| Mineral | Rock Type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-FPX1 | P-FPX2 | P-FPX3 | P-FPX4 | |

| BMS | 2.94 | 0.89 | 1.93 | 2.6 |

| Feldspar | 17.61 | 10.28 | 10.03 | 9.66 |

| Clinopyroxene | 11.75 | 17.38 | 17.2 | 19.15 |

| Orthopyroxene | 33.85 | 21.38 | 17.36 | 34.58 |

| Olivine | 10.13 | 9.19 | 4.41 | 2.94 |

| Serpentine | 7.34 | 13.96 | 19.15 | 4.23 |

| Chlorite | 4.62 | 7.62 | 8.78 | 9.51 |

| Other silicates | 5.62 | 5.81 | 9.8 | 12.5 |

| Chromite | 2.81 | 8.07 | 6.53 | 1.28 |

| Fe-Oxides | 2.28 | 3.4 | 4.44 | 1.78 |

| Carbonates | 0.7 | 1.26 | 0.35 | 1.69 |

| Other * | 0.35 | 0.77 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Mineral | Rock Type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPX1 | FPX2 | FPX3 | FPX4 | |

| Pentlandite | 20.24 | 25.37 | 18.23 | 26.22 |

| Millerite | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Chalcopyrite | 18.67 | 16.09 | 10.34 | 17.44 |

| Pyrrhotite | 60.32 | 57.48 | 69.98 | 54.88 |

| Pyrite | 0 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 1.19 |

| Other sulphides | 0.77 | 0.99 | 1.32 | 0.25 |

| Total | 100.01 | 99.99 | 100.01 | 100 |

| Mineral | Rock Type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-FPX1 | P-FPX2 | P-FPX3 | P-FPX4 | |

| Pentlandite | 24.85 | 35.71 | 20.47 | 32.25 |

| Millerite | <0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| Chalcopyrite | 17.97 | 17.29 | 19.51 | 18.12 |

| Pyrrhotite | 56.74 | 45.14 | 59.84 | 49.16 |

| Pyrite | 0.08 | 1.23 | <0.01 | 0.11 |

| Other sulphides * | 0.36 | 0.62 | 0.17 | 0.37 |

| Total | 100 | 100.01 | 100 | 100.01 |

| Mineral | Rock Type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPX1 | FPX2 | FPX3 | FPX4 | |

| Other sulphides | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.1 | 0.04 |

| Silicates | 12.38 | 8.13 | 7.52 | 7.92 |

| Chlorite | 0.88 | 0.63 | 0.56 | 2.27 |

| Mica | 0.09 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.28 |

| Chromite | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Fe-Oxides | 0.1 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.21 |

| Dolomite | 0.04 | 0.51 | 0.11 | 0.2 |

| Other * | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Free Surface | 86.3 | 89.68 | 91.04 | 88.93 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Mineral | Rock Type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-FPX1 | P-FPX2 | P-FPX3 | P-FPX4 | |

| Other sulphides | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Silicates | 2.59 | 4.25 | 3.38 | 3.32 |

| Chlorite | 3.37 | 6.28 | 6.48 | 1.18 |

| Mica | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.22 |

| Chromite | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0 |

| Fe-Oxides | 0.63 | 1.39 | 1.02 | 0.25 |

| Dolomite | 0.58 | 0.98 | 0.26 | 0.25 |

| Other | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| Free Surface | 92.35 | 86.62 | 88.43 | 94.74 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

References

- Nwaila, G.T.; Ghorbani, Y.; Becker, M.; Frimmel, H.E.; Petersen, J.; Zhang, S. Geometallurgical Approach for Implications of Ore Blending on Cyanide Leaching and Adsorption Behavior of Witwatersrand Gold Ores, South Africa. Nat. Resour. Res. 2020, 29, 1007–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rötzer, N.; Schmidt, M. Decreasing Metal Ore Grades—Is the Fear of Resource Depletion Justified? Resources 2018, 7, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooren, J.; Abo Atia, T. Combined microwave assisted roasting and leaching to recover platinum group metals from spent automotive catalysts. Miner. Eng. 2020, 146, 106153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philander, C.; Rozendaal, A. A process mineralogy approach to geometallurgical model refinement for the Namakwa Sands heavy minerals operations, west coast of South Africa. Miner. Eng. 2014, 65, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, A.; Shirazy, A.; Nazerian, H.; Khakmardan, S. Geochemical and Behavioral Modeling of Phosphorus and Sulfur as Deleterious Elements of Iron Ore to Be Used in Geometallurgical Studies, Sheytoor Iron Ore, Iran. Open J. Geol. 2021, 11, 596–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, S.A.B.; Silva, E.M.S.; Silva, A.C. Geometallurgical modeling and reconciliation with production data in a fhosphate mine. Concilium 2024, 24, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, F.C. Crushing & grinding calculations—Part I. Br. Chem. Eng. 1961, 6, 378–385. [Google Scholar]

- McClung, C.R.; Viljoen, F. Mineralogical Assessment of the Metamorphosed Broken Hill Sulfide Deposit, South Africa: Implications for Processing Complex Orebodies. In Proceedings of the 10th International Congress for Applied Mineralogy (ICAM); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnaird, J.A.; McDonald, I. Preface: An introduction to mineralisation in the northern limb of the Bushveld Complex. Trans. Inst. Min. Metall. Sect. B Appl. Earth Sci. 2005, 114, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawthorn, R.G.; Merkle, R.K.W.; Viljoen, M.J. Platinum-group element deposits in the Bushveld Complex, South Africa. In The Geology, Geochemistry, Mineralogy and Mineral Beneficiation of Platinum-Group Elements; Cabri, L.J., Ed.; Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2002; Volume 54, pp. 389–429. [Google Scholar]

- Cawthorn, R.G.; Lee, C.A.; Schouwstra, R.P.; Mellowship, P. Relationship between PGE and PGM in the bushveld complex. Can. Miner. 2002, 40, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, D.; Kinnaird, J.A. Complex Multistage Genesis for the Ni–Cu–PGE Mineralisation in the Southern Region of the Platreef, Bushveld Complex, South Africa. Appl. Earth Sci. 2005, 114, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, I.; Holwell, D.A. Geology of the Northern Bushveld Complex and the Setting and Genesis of the Platreef Ni-Cu-PGE Deposit. Magmatic Ni-Cu and PGE Deposits. Rev. Econ. Geol. 2011, 17, 297–327. [Google Scholar]

- Rule, C.; Schouwstra, R.P. Process Mineralogy Delivering Significant Value at Anglo Platinum Concentrator Operations. In Proceedings of the 10th International Congress for Applied Mineralogy (ICAM); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwanga, A.; Rosenkranz, J.; Lamberg, P. Testing of Ore Comminution Behavior in the Geometallurgical Context—A Review. Minerals 2015, 5, 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwanga, A.; Lamberg, P.; Rosenkranz, J. Comminution test method using small drill core samples. Miner. Eng. 2015, 72, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, L.; Mainza, A.N.; Becker, M.; Wiese, J.G. Using mineralogical and particle shape analysis to investigate enhanced mineral liberation through phase boundary fracture. Powder Technol. 2016, 1, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, M.A.W. Mineralogical control of minerals processing circuit design. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2004, 104, 307–309. [Google Scholar]

- Napier-Munn, T. Is progress in energy-efficient comminution doomed? Miner. Eng. 2015, 73, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouwstra, R.; De Vaux, D.; Muzondo, T.; Prins, C. A geometallurgical approach at Anglo American’s Mogalakwena operation. In Proceedings of the Second AusIMM International Conference, Brisbane, Australia, 30 September–2 October 2013; pp. 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Compan, G.; Pizarro, E.; Videla, A. Geometallurgical model of a copper sulphide mine for long-term planning. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2015, 115, 549–556. [Google Scholar]

- Lusambo, M.; Mulenga, F.K. Empirical model of recovery response of copper sulphide circuit at Kansanshi Mine. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Met. 2018, 118, 1179–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, J.T.; Auret, L. Machine learning applications in minerals processing: A review. Miner. Eng. 2019, 132, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraga, C.; Astudillo, C.A.; Estay, R.; Maranek, A. Enhancing Comminution Process Modeling in Mineral Processing: A Conjoint Analysis Approach for Implementing Neural Networks with Limited Data. Mining 2024, 4, 966–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.H.C.; Alves, V.K.; Souza, E.S. Machine learning for particle size prediction in iron ore grinding process. Peer Rev. 2024, 6, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera Ruiz, M.A.; Vega Gonzales, J.A.; Bailon Villalba, F.J. Multivariable predictive models for the estimation of power consumption (kW) of a Semi-autogenous mill applying Machine Learning algorithms [Modelos predictivos multivariables para la estimación de consumo de potencia (kW) de un molino Semi—Autógeno aplicando algoritmos de Machine Learning]. J. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 8, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loudari, C.; Cherkaoui, M.; Bennani, R.; El Harraki, I.; Fares, O.; El Adnani, M.; Abdelwahed, E.H.; Benzakour, I.; Bourzeix, F.; Baina, K. Predicting Grinding Mill Power Consumption in Mining: A Comparative Study. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th IEEE Congress on Information Science and Technology (CiSt), Essaouira, Morocco, 16–22 December 2023; pp. 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Both, C.; Dimitrakopoulos, R. Applied Machine Learning for Geometallurgical Throughput Prediction—A Case Study Using Production Data at the Tropicana Gold Mining Complex. Minerals 2021, 11, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, G.; Zhou, J.; Song, T.; Yang, J.; Li, K. Hierarchical Intelligent Control Method for Mineral Particle Size Based on Machine Learning. Minerals 2023, 13, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghipulile, T.; Moongo, T.; Dzinomwa, G.; Maweja, K.; Mapani, B.; Kurasha, J.; Amwaama, M. Effect of mineralogy on grindability—A case study of copper ores. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Met. 2023, 123, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarra, A.; Marambio, H.; Oyarzún, A.; Parra, R.; Mucciardi, F. Minerals and Metallurgical Processing. Syst. Dyn. DES Copp. Smelters 2017, 34, 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Navarra, A.; Menzies, A.; Jordens, A.; Waters, K. Strategic evaluation of concentror operational modes under geological uncertainty. Int. J. Min. Process 2017, 164, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarra, A.; Alvarez, M.; Rojas, K.; Menzies, A.; Pax, R.; Waters, K. Concentrator operational modes in response to geological variation. Miner. Eng. 2019, 134, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadani, K.; Asbjörnsson, G.; Bepswa, P.; Mainza, A.; Andrew, E.; Philipo, J.; Zulu, N.; Anyimadu, A.; Hulthén, E.; Evertsson, M. Simulation-Driven Development for Coarse Comminution Process—A Case Study of Geita Gold Mine, Tanzania Using Plantsmith Process Simulator. Proc. Des. Soc. 2021, 1, 2681–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou, S.C.; Dao, T.-M. Association rules mining approach to mineral processing control. Eng. Lett. 2010, 18, 156. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the IEEE ICNN’95—International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995; pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Niemann-Delius, C. Application of Particle Swarm Optimization to the Open Pit Mine Scheduling Problem. In Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium Continuous Surface Mining—Aachen 2014; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Luo, D.; Guo, K. Evaluation of mineral resources carrying capacity based on the particle swarm optimization clustering algorithm. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Met. 2020, 120, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Bo, L.; Yue, Y.; Wang, Y. Economic Optimal Allocation of Mine Water Based on Two-Stage Adaptive Genetic Algorithm and Particle Swarm Optimization. Sensors 2022, 22, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essa, K.S.; Elhussein, M. Interpretation of Magnetic Data Through Particle Swarm Optimization: Mineral Exploration Cases Studies. Nat. Resour. Res. 2020, 29, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essa, K.S.; Munschy, M. Gravity data interpretation using the particle swarm optimisation method with application to mineral exploration. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 128, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Ai, H.; Alvandi, A.; Lyu, C.; Wei, X.; Qin, Z.; Tu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Nie, T. Hunger Games Search for the elucidation of gravity anomalies with application to geothermal energy investigations and volcanic activity studies. Open Geosci. 2024, 16, 20220641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Luo, R.; Chen, Y.; Ge, X. Prediction model of asphalt pavement functional and structural performance using PSO-BPNN algorithm. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 407, 133534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Xu, Q.; Li, X. Research on performance prediction of asphalt pavement based on PSO-SVR model. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Machine Learning and Computer Application, Hangzhou, China, 27–29 October 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 850–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masasire, A.; Rwere, F.; Dzomba, P.; Mupa, M. A new preconcentration technique for the determination of PGMs and gold by fire assay and ICP-OES. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2022, 122, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarra, A.; Grammatikopoulos, T.; Waters, K. Incorporation of geometallurgical modelling into long-term production planning. Miner. Eng. 2018, 120, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Órdenes, J.; Toro, N.; Quelopana, A.; Navarra, A. Data-Driven Dynamic Simulations of Gold Extraction Which Incorporate Head Grade Distribution Statistics. Metals 2022, 12, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelSole, T.; Tippett, M. Principal Component Analysis. In Statistical Methods for Climate Scientists; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Q.; Li, B.B.; Lin, J.; Xie, B.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, Y.Q.; Zhu, K.G. Noise removal based on reconstruction of filtered principal components. Acta Geophys. Sin. 2015, 58, 2803–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pysmennyi, S.; Fedko, M.; Chukharev, S.; Rysbekov, K.; Kyelgyenbai, K.; Anastasov, D. Technology for mining of complex-structured bodies of stable and unstable ores. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 970, 12040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analysis for Research of Modern Bottom Sediments. Visnyk Taras Shevchenko Natl. Univ. Kyiv Geol. 2021, 93, 24–31. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Chen, J.; Fang, X.; Kuang, J.; Yu, W.; Ai, G. Pyrrhotite Mineral Processing Method Using Low-Alkali Process of Flotation Followed by Magnetic Separation. AU2020336795B2, 2 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ghedin, S.C.D.; Pedroso, G.J.; Neto, J.C.B.; Preve, N.B.; Gondoreck, G.G.; Ely, F.; Angioletto, E.; Ourique, F.; Ribeiro, L.F.B.; Frizon, T.E.A. Processing of pyrite derived from coal mining waste by density separation technique using lithium heteropolytungstate (LST). Matéria 2022, 27, e20220169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W. Selective Breakage of Mineralised Particles by High Voltage Pulse. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guldris, L.L.; Bengtsson, M. Selective Comminution Applied to Mineral Processing of a Tantalum Ore: A Technical, Economic Analysis. Minerals 2022, 12, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lvov, V.V.; Chitalov, L.S.; Lagov, P.B. Ore Hardness Properties Evaluation Based on Industrial Comminution Circuits Surveys. Eurasian Min. 2022, 38, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-García, E.; Bouchard, J.; Poulin, É. Integrating online mineral liberation data into process control and optimisation systems for grinding–separation plants. J. Process Control 2021, 105, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obasi, E.; Gundu, D.T.; Ashwe, A.; Akindele, M. Determination of Work Index of Enyigba Lead Ore, Ebonyi State, South-East Nigeria. Stud. Eng. Technol. 2015, 2, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzydlo, M.; Pawelczyk, M. Vibration measurements for copper ore milling and classification process optimization. Vibroeng. Procedia 2015, 6, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lotter, N.O.; Baum, W.; Reeves, S.; Arrué, C.; Bradshaw, D.J. The business vaalue of best practice process mineralogy. Miner. Eng. 2018, 116, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lithology | Rock Types | Bore Hole # | From (Metres) | To (Metres) | Difference Interval (Metres) | Rock Type Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPX | FPX1 | ZF101 | 1.212 | 1.219 | 7 | Feldspathic pyroxenite |

| FPX2 | ZF110 | 1.104 | 1.118 | 14 | ||

| FPX3 | ZF110 | 1.138 | 1.146 | 8 | ||

| FPX4 | ZF113 | 1.097 | 1.106 | 9 | ||

| P-FPX | P-FPX1 | ZF002 | 1.071 | 1.085 | 14 | Pegmatoidal feldspathic pyroxenite |

| P-FPX2 | ZF002 | 1.085 | 1.091 | 6 | ||

| P-FPX3 | ZF005 | 1.042 | 1.052 | 10 | ||

| P-FPX4 | ZF006 | 1.042 | 1.062 | 20 |

| Lithologies | Rock Types | Relative Density | BWI | Grind Size Achieved |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (g/cm) | (kWh/t) | (P80) | ||

| Feldspathic pyroxenite | FPX1 | 3.19 | 19.4 | 89 |

| FPX2 | 3.13 | 18.4 | 95 | |

| FPX3 | 3.17 | 21.3 | 78 | |

| FPX4 | 3.18 | 23.5 | 77 | |

| Pegmatoidal feldspathic pyroxenite | P-FPX1 | 3.21 | 23.36 | 77 |

| P-FPX2 | 3.32 | 25.14 | 87 | |

| P-FPX3 | 2.83 | 22.33 | 74 | |

| P-FPX4 | 2.89 | 23.15 | 78 |

| Campaigns | Lithology | Mineralogy Attributes (%) | BWI (kwt/h) | P80 (μm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorite | IronOxides | Silicates * | RD | ||||

| 1 | PFPX—Ore 1 in feed | 4.62 | 2.28 | 2.59 | 3.21 | 23.36 | 77 |

| FPX—Ore 2 in feed | 2.13 | 0.5 | 12.38 | 3.19 | 19.4 | 89 | |

| 2 | PFPX—Ore 1 in feed | 7.62 | 3.4 | 4.25 | 3.32 | 25.14 | 87 |

| FPX—Ore 2 in feed | 1.14 | 0.5 | 8.13 | 3.13 | 18.4 | 95 | |

| 3 | PFPX—Ore 1 in feed | 8.78 | 4.44 | 3.38 | 2.83 | 22.33 | 74 |

| FPX—Ore 2 in feed | 1.14 | 0.39 | 7.52 | 3.17 | 21.3 | 78 | |

| 4 | PFPX—Ore 1 in feed | 9.51 | 1.78 | 3.32 | 2.89 | 23.15 | 78 |

| FPX—Ore 2 in feed | 4.99 | 0.39 | 7.92 | 3.18 | 23.5 | 77 | |

| 5 | PFPX—Ore 1 in feed | 6.7 | 3.36 | 2.96 | 3.05 | 23.3 | 77 |

| FPX—Ore 2 in feed | 3.6 | 0.45 | 8.03 | 3.18 | 21.5 | 83 | |

| 6 | PFPX—Ore 1 in feed | 8.2 | 2.84 | 3.35 | 3.05 | 23.3 | 78 |

| FPX—Ore 2 in feed | 2.13 | 0.5 | 12.38 | 3.19 | 19.4 | 89 | |

| Chlorite | IronOxides | Silicates | BWI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorite | 1.00 | 0.74 | −0.74 | 0.71 |

| IronOxides | 0.74 | 1.00 | −0.88 | 0.51 |

| Silicates | −0.74 | −0.88 | 1.00 | −0.59 |

| BWI | 0.71 | 0.51 | −0.59 | 1.00 |

| Coefficient | Variable | Regressed Constant | SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C0 | (Intercept) | −0.089 | 0.036 | 0.014 |

| C1 | Chlorite | 0.781 | 0.030 | 3.729 |

| C2 | IronOxides | −0.798 | 0.065 | 3.205 |

| C3 | Silicates | −0.720 | 0.057 | 2.523 |

| C4 | RD | 0.591 | 0.040 | 6.253 |

| C5 | Chlorite*Silicates | 0.636 | 0.065 | 4.937 |

| C6 | IronOxides*RD | 0.048 | 0.022 | 0.028 |

| C7 | Silicates*RD | 0.154 | 0.045 | 0.000 |

| C8 | Chlorite2 | 0.120 | 0.041 | 0.003 |

| C9 | IronOxides2 | 0.207 | 0.025 | 9.376 |

| C10 | Silicates2 | 0.110 | 0.028 | 8.251 |

| C11 | RD2 | 0.076 | 0.012 | 6.412 |

| Model Statistics | Value |

|---|---|

| Root Mean Squared Error | 0.44 |

| R2 | 0.80 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.79 |

| RMS Error | 0.441 |

| F-statistic | 243 |

| p-Value | 2.29 * |

| Production Campaigns | Parameters | Mode A | Mode B | Deposit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | Contingency | Regular | Contingency | |||

| 1 | Throughput (t/h) | 503.00 | 386.00 | 444 | ||

| Low-grade PGM (PFPX) % | 46.13 | 10.00 | 51.78 | 90.00 | 25 | |

| High-grade PGM (FPX) % | 53.87 | 90.00 | 48.22 | 10.00 | 75 | |

| 2 | Throughput (t/h) | 535.00 | 362.73 | 449 | ||

| Low-grade PGM (PFPX) % | 47.98 | 10.00 | 55.57 | 90.00 | 25 | |

| High-grade PGM (FPX) % | 52.02 | 90.00 | 44.43 | 10.00 | 75 | |

| 3 | Throughput (t/h) | 487.00 | 431.00 | 459 | ||

| Low-grade PGM (PFPX) % | 48.80 | 10.00 | 50.91 | 90.00 | 25 | |

| High-grade PGM (FPX) % | 51.20 | 90.00 | 49.09 | 10.00 | 75 | |

| 4 | Throughput (t/h) | 497.00 | 434.00 | 466 | ||

| Low-grade PGM (PFPX) % | 47.92 | 10.00 | 50.01 | 90.00 | 25 | |

| High-grade PGM (FPX) % | 52.08 | 90.00 | 49.99 | 10.00 | 75 | |

| 5 | Throughput (t/h) | 502.00 | 423.00 | 462 | ||

| Low-grade PGM (PFPX) % | 47.17 | 10.00 | 50.01 | 90.00 | 25 | |

| High-grade PGM (FPX) % | 52.83 | 90.00 | 49.99 | 10.00 | 75 | |

| 6 | Throughput (t/h) | 511.00 | 414.00 | 463 | ||

| Low-grade PGM (PFPX) % | 46.54 | 10.00 | 50.18 | 90.00 | 25 | |

| High-grade PGM (FPX) % | 53.46 | 90.00 | 49.82 | 10.00 | 75 | |

| Existing Processing Model | Improved Processing Model |

|---|---|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kabemba, A.M.; Mutombo, K.; Waters, K.E. Towards a Dynamic Optimisation of Comminution Circuit Under Geological Uncertainties. Processes 2025, 13, 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13020443

Kabemba AM, Mutombo K, Waters KE. Towards a Dynamic Optimisation of Comminution Circuit Under Geological Uncertainties. Processes. 2025; 13(2):443. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13020443

Chicago/Turabian StyleKabemba, Alain M., Kalenda Mutombo, and Kristian E. Waters. 2025. "Towards a Dynamic Optimisation of Comminution Circuit Under Geological Uncertainties" Processes 13, no. 2: 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13020443

APA StyleKabemba, A. M., Mutombo, K., & Waters, K. E. (2025). Towards a Dynamic Optimisation of Comminution Circuit Under Geological Uncertainties. Processes, 13(2), 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13020443