Aloe vera as Promising Material for Water Treatment: A Review

Abstract

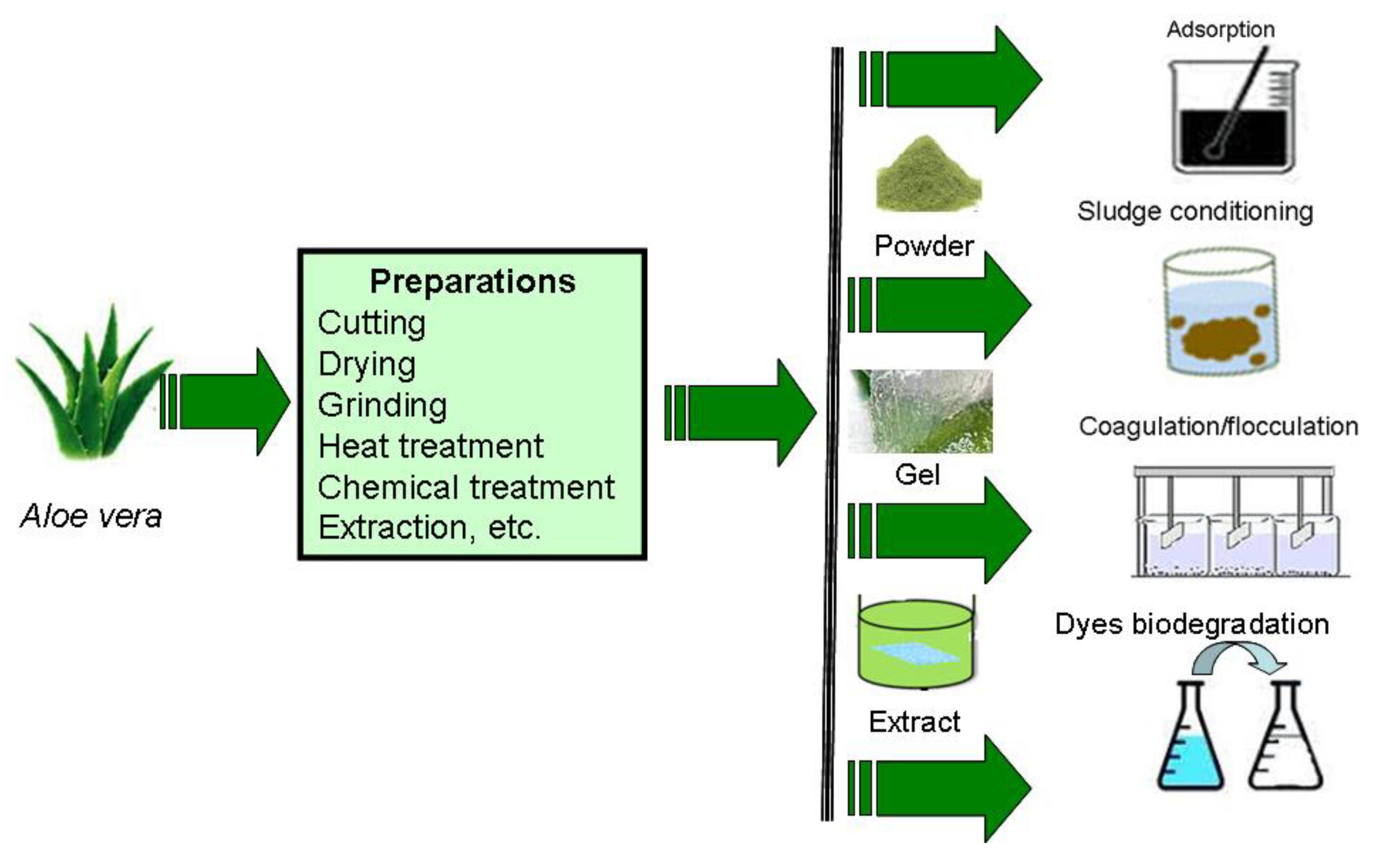

:1. Introduction

2. Aloe vera as Coagulant/Flocculant for Wastewater Treatment

3. Aloe Vera as Biosorbent for Pollutant Removal

4. Aloe vera Gel as Flocculant for Wastewater Sludge Treatment

5. Aloe vera for Textile Dyes Biodegradation

6. Factors Making Aloe vera a Promising Material for Water Treatment

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jonathan, M.; Srinivasalu, S.; Thangadurai, N.; Ayyamperumal, T.; Armstrong-Altrin, J.; Ram-Mohan, V. Contamination of Uppanar River and coastal waters off Cuddalore, Southeast coast of India. Environ. Geol. 2008, 53, 1391–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govil, P.; Sorlie, J.; Murthy, N.; Sujatha, D.; Reddy, G.; Rudolph-Lund, K.; Krishna, A.; Mohan, K.R. Soil contamination of heavy metals in the Katedan industrial development area, Hyderabad, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2008, 140, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raju, N.J.; Ram, P.; Dey, S. Groundwater quality in the lower Varuna river basin, Varanasi district, Uttar Pradesh. J. Geol. Soc. India 2009, 73, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, T.A.; Lo, W.; Chan, G.; Sillanpää, M.E. Biological processes for treatment of landfill leachate. J. Environ. Monit. 2010, 12, 2032–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesaro, A.; Naddeo, V.; Belgiorno, V. Wastewater treatment by combination of advanced oxidation processes and conventional biological systems. J. Bioremediat. Biodegrad. 2013, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Amuda, O.; Alade, A. Coagulation/flocculation process in the treatment of abattoir wastewater. Desalination 2006, 196, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gohary, F.; Tawfik, A.; Mahmoud, U. Comparative study between chemical coagulation/precipitation (C/P) versus coagulation/dissolved air flotation (C/DAF) for pre-treatment of personal care products (PCPs) wastewater. Desalination 2010, 252, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, B.; Chavez, A.; Leyva, A.; Tchobanoglous, G. Sand and synthetic medium filtration of advanced primary treatment effluent from Mexico City. Water Res. 2000, 34, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crini, G.; Lichtfouse, E. Advantages and disadvantages of techniques used for wastewater treatment. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, B.; Loss, R.D.; Shields, D.; Pawlik, T.; Hochreiter, R.; Zydney, A.L.; Kumar, M. Polyacrylamide degradation and its implications in environmental systems. NPJ Clean Water 2018, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, D.P.; Lentz, R.D.; Cahn, M.D.; Ogle, R.S.; Rothert, A.K.; Lydy, M.J. Toxicity of anionic polyacrylamide formulations when used for erosion control in agriculture. J. Environ. Qual. 2009, 38, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crini, G.; Badot, P.-M. Application of chitosan, a natural aminopolysaccharide, for dye removal from aqueous solutions by adsorption processes using batch studies: A review of recent literature. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2008, 33, 399–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, V.R.; Vairagade, V.S.; Kedar, A.P. Activated carbon as adsorbent in advance treatement of wastewater. IOSR J. Mech. Civ. Eng. 2017, 14, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Regeneration of exhausted activated carbon by electrochemical method. Chem. Eng. J. 2002, 85, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadhraoui, M.; Sellami, M.; Zarai, Z.; Saleh, K.; Ben Rebah, F.; Leduc, R. Cacus juice preparation as bioflocculant: Proerties, characteristics and application. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2019, 18, 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Amari, A.; Alalwan, B.; Eldirderi, M.M.; Mnif, W.; Ben Rebah, F. Cactus material-based adsorbents for the removal of heavy metals and dyes: A review. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 7, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Rebah, F.; Siddeeg, S. Cactus an eco-friendly material for wastewater treatment: A review. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2017, 8, 1770–1782. [Google Scholar]

- He, W.; Xie, Z.; Lu, W.; Huang, M.; Ma, J. Comparative analysis on floc growth behaviors during ballasted flocculation by using aluminum sulphate (AS) and polyaluminum chloride (PACl) as coagulants. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 213, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, N.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, D.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q. Coagulation behavior of polyaluminum chloride: Effects of pH and coagulant dosage. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2015, 23, 1041–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edzwald, J.K.; Haarhoff, J. Seawater pretreatment for reverse osmosis: Chemistry, contaminants, and coagulation. Water Res. 2011, 45, 5428–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyn, C.N.; Osmonda, C.; Edwardson, J.A.; Barker, D.J.P.; Harris, E.C.; Lacey, R.F. Geographical Relation Between Alzheimer’s Disease and Aluminum in Drinking Water. Lancet 1989, 333, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkurunziza, T.; Nduwayezu, J.B.; Banadda, E.N.; Nhapi, I. The effect of turbidity levels and Moringa oleifera concentration on the effectiveness of coagulation in water treatment. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 59, 1551–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, V.; Munavalli, G. Turbidity removal by conventional and ballasted coagulation with natural coagulants. Appl. Water Sci. 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daza, R.; Barajas Solano, A.F.; Epalza Contreras, J.M. Evaluation of the efficiency of bio-polymers derived from desertic plants as flocculation agents. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2016, 49, 361–366. [Google Scholar]

- Adugna, A.T.; Gebresilasie, N.M. Aloe steudneri gel as natural flocculant for textile wastewater treatment. Water Pract. Technol. 2018, 13, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwini Prabhakar, S.; Ojha, N.; Das, N. Application of Aloe vera mucilage as bioflocculant for the treatment of textile wastewater: Process optimization. Water Sci. Technol. 2020, 82, 2446–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.E.; Hanafiah, M.M.; Halim, A.A.; Mahmud, M.H. Primary treatment of dye wastewater using Aloe vera-aided aluminium and magnesium hybrid coagulants. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 30, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bazrafshan, E.; Mohammadi, L.; Mostafapour, F.K. Survey efficiency of coagulation process with polyaluminum chloride using aloe vera as coagulant aid for arsenic removal from aqueous solutions. Wulfenia J. 2013, 20, 323–341. [Google Scholar]

- Ezeamaku, U.; Chike-Onyegbula, C.; Eze, I.; Iheaturu, N.; Dunu, S.; Osueke, W.; Onuchukwu, S. Removal of Copper Ions from Waste Water by Coagulation by Using Magnesium Chloride and Aloe Vera Leaves. Futo J. Ser. 2019, 5, 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav, M.V.; Mahajan, Y.S. Assessment of feasibility of natural coagulants in turbidity removal and modeling of coagulation process. Desalin. Water Treat. 2014, 52, 5812–5821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, H.S.; Shinde, S.A.; Raut, G.A.; Nawale, N.P.; Hakke, A.; Deosarkar, M. Use of Aloe-vera gel as natural coagulant in treatment of drinking water. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Res. Eng. Trends 2020, 5, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Jinna, A.; Anu, M.; Krishnan, N.; Sanal, V.; Das, L. Comparative study of efficiency of local plants in water treatment. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2019, 6, 4046–4052. [Google Scholar]

- Pallar, B.M.; Abram, P.H.; Ningsih, P. Analysis of Hard Water Coagulation in Water Sources of Kawatuna using Aloe Vera Plant. J. Akad. Kim. 2020, 9, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irma, N.Y.A.E.; Philippe, S.; Abdoukarim, A.; Alassane, Y.A.K.; Pascal, A.C.; Daouda, M.; Dominique, S.K.C. Evaluation of Aloe vera leaf gel as a Natural Flocculant: Phytochemical Screening and Turbidity removal Trials of water by Coagulation flocculation. Res. J. Recent Sci. 2016, 5, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Saratha Priya, S.; Kumar, M.K.S. Physio Chemical Treatment On Municipal Waste Water In Tuticorin Region Using Natural Coagulants. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2018, 6, 3221–5687. [Google Scholar]

- Da Luz, T.G.; Sales, V.; da Rocha, R.D.C. Evaluation of technology potential of Aloe arborescens biopolymer in galvanic effluent treatment. Water Sci. Technol. 2018, 2017, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abirami, P.; Devi, N.; Sharmila, S. Flocculant effect of Aloe vera L. in removing pollutants from raw and treated dye industry effluent. Asian J. Environ. Sci. 2010, 5, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zin, N.S.B.M.; Kamaruzaman, W.N.B.; Lee, C.S. Study the effectiveness of biocoagulant between Aloe vera (L.). Burm. F and Okra mucilage in coagulation and flocculation Treatment. In e-Prosiding Seminar ENVIROPOLY 2016; Oleh, D., Penerbit, P., Eds.; Politeknik Sultan Idris Shah: Selangor, Malaisie, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Muruganandam, L.; Saravana Kumar, M.P.; Jena, A.; Gulla, S.; Godhwani, B. Treatment of waste water by coagulation and flocculation using biomaterials. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 263, 032006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amruta, G.; Munavalli, G. Use of aloe vera as coagulant aid in turbidity removal. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2017, 10, 4362–4365. [Google Scholar]

- Sellami, M.; Khadraoui, M.; Zarat, Z.; Jdidi, N.; Ben Rebah, F. Cactus juice as flocculant in the coagulation-flocculation process for industrial wastewater treatment: Comparative study with polyacrylamide. Water Sci. Technol. 2014, 70(7), 1175–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Crini, G.; Badot, P.-M. Sorption Processes and Pollution: Conventional and Non-Conventional Sorbents for Pollutant Removal from Wastewaters; Presses University Franche-Comté: Besançon, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Douven, S.; Paez, C.A.; Gommes, C.J. The range of validity of sorption kinetic models. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 448, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malkoc, E.; Nuhoglu, Y. Determination of kinetic and equilibrium parameters of the batch adsorption of Cr (VI) onto waste acorn of Quercus ithaburensis. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2007, 46, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthäus, B.; Özcan, M.M. Habitat effects on yield, fatty acid composition and tocopherol contents of prickly pear (Opuntia ficus-indica L.) seed oils. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 131, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tichaona, N.; Maria, M.N.; Emaculate, M.; Fidelis, C.; Upenyu, G.; Benias, N. Isotherm Study of the Biosorption of Cu (II) from Aqueous Solution by Vigna Subterranea (L.) Verdc Hull. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2013, 2, 119–206. [Google Scholar]

- Mahfoudhi, N.; Boufi, S. Nanocellulose as a novel nanostructured adsorbent for environmental remediation: A review. Cellulose 2017, 24, 1171–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyzas, G.Z.; Kostoglou, M. Green adsorbents for wastewaters: A critical review. Materials 2014, 7, 333–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Kaur, H.; Sharma, M.; Sahore, V. A review on applicability of naturally available adsorbents for the removal of hazardous dyes from aqueous waste. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011, 183, 151–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi, Z.; Aghaie, H.; Fazaeli, R. Application of response surface methodology for optimization of cadmium removal by Aloe Vera/carboxylated carbon nanotubes nanocomposite-based low-cost adsorbent. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 065015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, A. Biosorption of Ni (II) ions from aqueous solution using modified Aloe barbadensis Miller leaf powder. Water Sci. Eng. 2019, 12, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapashi, E.; Kapnisti, M.; Dafnomili, A.; Noli, F. Aloe Vera as an effective biosorbent for the removal of thorium and barium from aqueous solutions. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2019, 321, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, V.; Srivastava, S.; Dwivedi, A. Aloe vera Burm. F. A potential botanical tool for bioremediation of arsenic. Sch. J. Agric. Vet. Sci. 2016, 3, 480–482. [Google Scholar]

- Prajapati, A.K.; Das, S.; Mondal, M.K. Exhaustive studies on toxic Cr (VI) removal mechanism from aqueous solution using activated carbon of Aloe vera waste leaves. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 307, 112956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, R.; Lata, S.; Singhal, S. Removal of heavy metal from wastewater by the use of modified aloe vera leaf powder. Int. J. Basic Appl. Chem. Sci. 2015, 5, 6–17. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.; Sharma, S.; Jain, A.; Mandal, M.; Pandey, P.K. Removal of copper ion from synthetic wastewater using Aloe vera as an adsorbent. Eur. J. Adv. Eng. Technol. 2017, 4, 249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Vélez, E.; Campillo, G.; Morales, G.; Hincapié, C.; Osorio, J.; Arnache, O. Silver nanoparticles obtained by aqueous or ethanolic aloe Vera extracts: An assessment of the antibacterial activity and mercury removal capability. J. Nanomater. 2018, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Namavari, S.; Moeinpour, F. Use of Aloe Vera Shell Ash Supported Ni 0.5 Zn 0.5 Fe2O4 Magnetic Nanoparticles for Removal of Pb (Ii) from Aqueous Solutions. Environ. Health Eng. Manag. J. 2016, 3, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sruthi, R.; Shabari, M. Removal of lead from textile effluent using Citrus aurantium peel adsorbent and Aloe barbadensis gel adsorbent. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 5, 3881–3885. [Google Scholar]

- Primo, J.d.O.; Bittencourt, C.; Acosta, S.; Sierra-Castillo, A.; Colomer, J.-F.; Jaerger, S.; Teixeira, V.C.; Anaissi, F.J. Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles by Ecofriendly Routes: Adsorbent for Copper Removal From Wastewater. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 571790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noli, F.; Kapashi, E.; Kapnisti, M. Biosorption of uranium and cadmium using sorbents based on Aloe vera wastes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 102985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigzadeh, P.; Moeinpour, F. Fast and efficient removal of silver (I) from aqueous solutions using aloe vera shell ash supported Ni0. 5Zn0. 5Fe2O4 magnetic nanoparticles. Trans. Nonferr. Met. Soc. China 2016, 26, 2238–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuthahir, K.S.; Pragathiswaran, C.; Govindhan, P.; Abbubakkar, B.M.; Sridevi, V. Adsorption of Malachite Green dye onto activated carbon obtained from the natural plant stem. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Chem. 2017, 7, 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, G.; Sas, S.; Wadhwa, S.; Mathur, A.; McLaughlin, J.; Roy, S.S. Aloe vera assisted facile green synthesis of reduced graphene oxide for electrochemical and dye removal applications. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 26680–26688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanafiah, M.A.K.M.; Jamaludin, S.Z.M.; Khalid, K.; Ibrahim, S. Methylene blue adsorption on Aloe vera rind powder: Kinetics, Isotherm and Mechanisms. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2018, 17, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Malakootian, M.; Jafari Mansoorian, H.; Alizadeh, M.; Baghbanian, A. Phenol Removal from Aqueous Solution by Adsorption Process: Study of The Nanoparticles Performance Prepared from Alo vera and Mesquite (Prosopis) Leaves. Sci. Iran. 2017, 24, 3041–3052. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoodi, Z.; Aghaie, H.; Fazaeli, R. Adsorption Study of Reactive Violet 8 and Congo Red Dyes onto Aloe Vera Micropowder Impregnated with Cu Atoms as a Natural Modified Sorbent and Related Kinetics and Thermodynamics. Phys. Chem. Res. 2019, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar]

- Batool, M.; Qureshi, M.Z.; Hashmi, F.; Mehboob, N.; Shah, A.S. Congo red azo dye removal and study of its kinetics by aloe vera mediated copper oxide nanoparticles. Indones. J. Chem. 2011, 19, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Azazy, M.; Dimassi, S.N.; El-Shafie, A.S.; Issa, A.A. Bio-waste Aloe vera leaves as an efficient adsorbent for titan yellow from wastewater: Structuring of a novel adsorbent using Plackett-Burman factorial design. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khaniabadi, Y.O.; Heydari, R.; Nourmoradi, H.; Basiri, H.; Basiri, H. Low-cost sorbent for the removal of aniline and methyl orange from liquid-phase: Aloe vera leaves wastes. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 68, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakootian, M.; Mansoorian, H.J.; Yari, A.R. Removal of reactive dyes from aqueous solutions by a non-conventional and low cost agricultural waste: Adsorption on ash of Aloe Vera plant. Iran. J. Health Saf. Environ. 2014, 1, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Teng, T.T.; Alkarkhi, A.F.; Rafatullah, M.; Low, L.W. Chemical modification of imperata cylindrica leaf powder for heavy metal ion adsorption. WaterAir Soil Pollut. 2013, 224, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argun, M.E.; Dursun, S.; Ozdemir, C.; Karatas, M. Heavy metal adsorption by modified oak sawdust: Thermodynamics and kinetics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 141, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakirullah, M.; Ahmad, I.; Shah, S. Sorption studies of nickel ions onto sawdust of Dalbergia sissoo. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2006, 53, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Çekim, M.; Yildiz, S.; Dere, T. Biosorption of copper from synthetic waters by using tobacco leaf: Equilibrium, inetic and thermodynamic tests. J. Environ. Eng. Landsc. Manag. 2015, 23, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.P.; King, P.; Prasad, V. Equilibrium and kinetic studies for the biosorption system of copper (II) ion from aqueous solution using Tectona grandis Lf leaves powder. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 137, 1211–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makeswari, M.; Santhi, T. Use of Ricinus communis leaves as a low-cost adsorbent for removal of Cu (II) ions from aqueous solution. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2014, 40, 1157–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheraghi, E.; Ameri, E.; Moheb, A. Adsorption of cadmium ions from aqueous solutions using sesame as a low-cost biosorbent: Kinetics and equilibrium studies. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 12, 2579–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.S.; Anand, S.; Venkateswarlu, P. Adsorption of cadmium from aqueous solution by Ficus religiosa leaf powder and characterization of loaded biosorbent. Clean Soil Air Water 2011, 39, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppusamy, S.; Thavamani, P.; Megharaj, M.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Lee, Y.B.; Naidu, R. Potential of Melaleuca diosmifolia leaf as a low-cost adsorbent for hexavalent chromium removal from contaminated water bodies. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2016, 100, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangabhashiyam, S.; Nakkeeran, E.; Anu, N.; Selvaraju, N. Biosorption potential of a novel powder, prepared from Ficus auriculata leaves, for sequestration of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solutions. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2015, 41, 8405–8424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez-Cid, A.; Velázquez-Ugalde, I.; Herrera-González, A.; García-Serrano, J. Textile dyes removal from aqueous solution using Opuntia ficus-indica fruit waste as adsorbent and its characterization. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 130, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Barakat, M. Decolourization of hazardous brilliant green from aqueous solution using binary oxidized cactus fruit peel. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 226, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Qi, Y.; Gao, C. Chemical regeneration of spent powdered activated carbon used in decolorization of sodium salicylate for the pharmaceutical industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 86, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El maguana, Y.; Elhadiri, N.; Benchanaa, M.; Chikri, R. Adsorption Thermodynamic and Kinetic Studies of Methyl Orange onto Sugar Scum Powder as a Low-Cost Inorganic Adsorbent. J. Chem. 2020, 2020, 9165874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, F.; Alahiane, S.; Sennaoui, A.; Dinne, M.; Bakas, I.; Assabbane, A. Removal of cationic dye (Methylene Blue) from aqueous solution by adsorption on two type of biomaterial of South Morocco. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 22, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkarim, S.; Mohammed, H.; Nouredine, B. Sorption of methylene blue dye from aqueous solution using an agricultural waste. Trends Green Chem. 2017, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana, J.M.R.R.; Mazzoco, R.R. Adsorption studies of methylene blue and phenol onto black stone cherries prepared by chemical activation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 180, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Qiu, K. Preparation of activated carbons from walnut shells via vacuum chemical activation and their application for methylene blue removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 165, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, C.; Imamoglu, M.; Turhan, Y.; Boysan, F. Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solutions using phosphoric acid activated carbon produced from hazelnut husks. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2012, 94, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malarvizhi, R.; Ho, Y.-S. The influence of pH and the structure of the dye molecules on adsorption isotherm modeling using activated carbon. Desalination 2010, 264, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadhil, O.H.; Eisa, M.Y. Removal of Methyl Orange from Aqueous Solutions by Adsorption Using Corn Leaves as Adsorbent Material. J. Eng. 2019, 25, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krika, F.; Benlahbib, O.E.F. Removal of methyl orange from aqueous solution via adsorption on cork as a natural and low-coast adsorbent: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic study of removal process. Desalin. Water Treat. 2015, 53, 3711–3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaouadi, T.; Hajji, M.; Kasmi, M.; Kallel, A.; Chatti, A.; Hamzaoui, H.; Mnif, A.; Tizaoui, C.; Trabelsi, I. Aloe sp. leaf gel and water glass for municipal wastewater sludge treatment and odour removal. Water Sci. Technol. 2020, 81, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rai, M.S.; Bhat, P.R.; Prajna, P.; Jayadev, K.; Rao, P.V. Degradation of malachite green and congo red using Aloe barabadensis mill extract. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 330–340. [Google Scholar]

- Devis, P.; Robson, M. Anti-inflammatory and wound healing of growth substances in Aloe vera. J. Am. Pediatr. Med. Assoc. 1999, 84, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oturkar, C.C.; Nemade, H.N.; Mulik, P.M.; Patole, M.S.; Hawaldar, R.R.; Gawai, K.R. Mechanistic investigation of decolorization and degradation of Reactive Red 120 by Bacillus lentus BI377. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebresamuel, N.; Gebre-Mariam, T. Comparative physico-chemical characterization of the mucilages of two cactus pears (Opuntia spp.) obtained from Mekelle, Northern Ethiopia. J. Biom. Nanobiotechnol. 2012, 3, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adki, V.S.; Jadhav, J.P.; Bapat, V.A. Exploring the phytoremediation potential of cactus (Nopalea cochenillifera Salm. Dyck.) cell cultures for textile dye degradation. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2012, 14, 554–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooh, M.R.; Lim, L.B.; Lim, L.H.; Dhari, M.K. Phytoremediation capability of Azolla pinnata for the removal of malachite green from aqueous solution. J. Environ. Biotechnol. Res. 2016, 5, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Torbati, S. Feasibility and assessment of the phytoremediation potential of duckweed for triarylmethane dye degradation with the emphasis on some physiological responses and effect of operational parameters. Turk. J. Biol. 2015, 39, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torbati, S. Artificial neural network modeling of biotreatment of malachite green by Spirodela polyrhiza: Study of plant physiological responses and the dye biodegradation pathway. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2016, 99, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, A.; Bordoloi, M.; Baruah, H.P.D. Aloe vera: A multipurpose industrial crop. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016, 94, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanizadeh, N.; Ghiasi-Esfahani, H. Qualitative improvement of low meat beef burger using Aloe vera. Meat Sci. 2015, 99, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.Z.; Chang, H.-L.; Kilbane, J.J., II. Removal and recovery of metal ions from wastewater using biosorbents and chemically modified biosorbents. Bioresour. Technol. 1996, 57, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maan, A.A.; Nazir, A.; Khan, M.K.I.; Ahmad, T.; Zia, R.; Murid, M.; Abrar, M. The therapeutic properties and applications of Aloe vera: A review. J. Herb. Med. 2018, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. Chemical Constitution, Health Benefits and Side Effects of Aloe Vera. Indian J. Res. 2015, 4, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayaraghavan, G.; Sivakumar, T.; Kumar, A.V. Application of plant based coagulants for waste water treatment. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Res. Stud. 2011, 1, 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sepúlveda, E.; Sáenz, C.; Aliaga, E.; Aceituno, C. Extraction and characterization of mucilage in Opuntia spp. J. Arid Environ. 2007, 68, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamman, J.H. Composition and applications of Aloe vera leaf gel. Molecules 2008, 13, 1599–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nidiry, E.S.J.; Ganeshan, G.; Lokesha, A. Antifungal activity of some extractives and constituents of Aloe vera. Res. J. Med. Plant 2011, 5, 196–200. [Google Scholar]

- Radha, M.H.; Laxmipriya, N.P. Evaluation of biological properties and clinical effectiveness of Aloe vera: A systematic review. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2015, 5, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Effluents | Preparation | Operating Conditions | Removal Efficiencies | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| River water 7 NTU | AV gel blended and mixed with H2O (1% v/v) | AV as coagulant aid (10 mg/L) with Moringa oleifera (10 mg/L) | Turbidity: 42.85% | [23] |

| 21 NTU | AV gel blended and mixed with H2O (1% v/v) | AV as coagulant aid (10 mg/L) with Moringa oleifera (50 mg/L) | Turbidity: 85.71% | [23] |

| 35 NTU | AV gel blended and mixed with H2O (1% v/v) | AV gel as coagulant aid (10 mg/L) with Moringa oleifera (100 mg/L) | Turbidity: 91.42% | [23] |

| Drinking raw water Turbidity: 44,5 NTU Color: 375 UPt-Co, pH 7 | Sun dried AV | 25 mg/L as flocculant | Turbidity: 92.74% Color: 95.73% | [24] |

| Textile wastewater Turbidity: 190 NTU COD: 410 mg/L BOD5: 335 mg/L TSS: 380 mg/L Pb: mg/L pH 5.1, 37 °C | AV gel mixed H2O, stirred 30 min, strained (25 mm sieve) and filtrate recuperation | Flocculant dose: 33 mL/L, mixing time 20 min, pH 7.3, 61 rpm | Turbidity: 92.3% COD: 76.8% BOD5: 83.5% TSS: 57.9% Pb: 77% | [25] |

| Methylene blue | AV blended with magnesium sulphate (10:90%) at room temperature, 24 h | Dosage: 3000 mg/L as coagulant, pH 12.5 | 60–70% | [27] |

| Methylene blue | AV blended with magnesium sulphate (10:90%) at room temperature, 24 h | Dosage: 3000 mg/L as coagulant, pH 12.5 | 50–55% | [27] |

| As(V) aqueous solution (Na2HAsO4.7H2O) 0.2–1 mg/L | AV leaves washed with deionized water, cut into small pieces, dried (333 K), ground and sieved (100 mesh) | Dose of AV as coagulant: 2.0 mg/L, dose of polyaluminum chloride: 3 mg/L, pH 5 | 92.63% | [28] |

| As(V) aqueous solution: 0.2–1 mg/L | AV leaves washed with H2O, cut into small pieces, dried (333 K), ground and sieved (100 mesh) | 0.1 mg/L AV ascoagulant versus 3 mg/L polyaluminum chloridepH 5 | 21–93.1%. | [28] |

| River water Cu: 2000 mg/L | AV powder | Coagulant dose: 1200 mg/L; settling time: 40 min, pH 8, 313 K | 30.59% | [29] |

| Indrayani stream water: Turbidity: 45.5 NTU Alkalinity: 70 mg/L, pH 7.78 | 56 mg/L of alum with 5 mg/L of liquid AV as coagulation aid | Turbidity: 96.5% | [31] | |

| Indrayani stream water: Turbidity: 101 NTU Alkalinity: 65 mg/L. pH 7.1 | 24 mg/L of alum with 14 mg/L of AV as coagulation aid | Turbidity: 98.5% | [31] | |

| Indrayani stream water: Turbidity: 45.5 NTU Alkalinity: 70 mg/L, pH 7.78 | AV blend | 56 mg/L of alum with 10 mg/L of liquid AV as flocculation aid | Turbidity: 96.2% | [31] |

| Indrayani stream water: stream: Turbidity: 101 NTU Alkalinity: 65 mg/L pH 7.1 | AV blend | 56 mg/L of alum with 10 mg/L of liquid AV as flocculation aid | Turbidity: 96.2% | [31] |

| Surface water Turbidity: 40–100 NTU | AV gel blended and mixed with H2O | 4 mL/L, 308 K, pH 4–8 | Turbidity: 50–65% | [32] |

| Surface water Turbidity: 12 NTU TDS: 1472 mg/L Color: 137 TCU | AV gel | 1 mL/L, pH 4.1, 303 K | Turbidity: 58.33% TDS: 77.51% Color: 50.36% | [33] |

| Surface water Turbidity: 186.8 NTU SS: 163 mg/L Color: 278 (Pt/Co) pH 7.37 | AV gel mixed with H2O, stirred and strained (25 mm mesh) and filtrate recuperation | Dose: 10 mL/L as flocculant | Turbidity: 72% SS: 91% Color: 15% | [34] |

| Textile wastewater COD: 1215 mg/L BOD: 593.33 mg/L TSS: 3768 mg/L TDS: 3754 mg/L | Powdered bioflocculant extracted from dehydrated pieces of AV leaves (313 K) | Dosage: 60 mg/L, pH 5, contact time: 180 min | FA: 82% COD: 90.53% TSS: 98.19% TDS: 98.80% | [35] |

| Municipal wastewater Turbidity: 54.1–66.1 NTU TDS: 734.12–784.09 mg/L TSS: 218.22 to 239.10 mg/LpH 7.2–8.4 | AV gel blended and mixed with H2O | 150 mL of AV gel, 10 mL of alum as coagulant, pH 8 | Turbidity: 67.72% | [35] |

| Electroplating industrial wastewater: BOD5: 32.5 mg/L COD: 220 mg/L DS: 9.4 mg/L SS: 3540 mg/L Cr(VI): 785 mg/L, pH 2.6 | Frozen AV gel (277 K), extracted and lyophilized | AV polymer: 0.50–2.5 g/L, Aluminum sulphate: 500–1000 mg/L, pH: 2.5–5.5 | Cr(VI): 6.37–37.74% DS: 89.80–94.13% SS: 71.06–90.00% | [36] |

| Dye industry effluent TDS: 6389 mg/L COD: 415.7 mg/L BOD: 150 mg/L | AV gel | 100 g of AV gel (20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100%) added to water at boiling temperature | TDS: 1.8–3.5% COD: 3.23–33.05% BOD: 15.78–53.33% | [37] |

| River water Cu: 2000 mg/L | AV powder | Coagulant dose: 1200 mg/L; settling time: 40 min, pH 8, 313 K | 30.59% | [29] |

| River water Cu: 2 g/L | AV powder | Coagulant dose:1200 mg/L; settling time: 40 min, pH 8, 313 K | 30.59% | [29] |

| Municipal wastewater Turbidity: 176 NTU. TSS: 3.4635 mg/L | AV pulp blended, 1000 mg was mixed with 100 mL of H2O | Dosage of 3 mL (30% AV pulp), pH 6–7 | Turbidity: 77.05% TSS: 74%. | [38] |

| Synthetic water: Turbidity: 55.0 NTU COD: 376.23 mg/L pH 7.4 | AV leaves gel | 1%, 2% and 5% of AV gel | Turbidity: 51.72% COD: 59.20% | [39] |

| Tannery Wastewater Turbidity: 74.43 NTU COD: 502.6 mg/L pH 7.8 | AV leaves gel | 5% of AV gel | Turbidity: 46.76% COD: 52.60% | [39] |

| Artificial turbid water Turbidity: 70–90 NTU | AV gel blended and mixed with H2O (1% v/v) | AV as coagulant aid (7%) with alum (10 mg/L) | Turbidity: 76–81% | [40] |

| Artificial turbid water Turbidity: 20–30 NTU | AV gel blended and mixed with H2O (1% v/v) | AV as coagulant aid (7%) with alum (10 mg/L) | Turbidity: 60–65%. | [40] |

| Effluents | Aloe vera Preparation | Removal Efficiency (R in %)/Biosorption Capacity (q in mg/g)/Used Conditions/Isotherm | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cd(II) aqueous solution (20–50 mg/L) | AV leaves crushed, powdered and sieved (200 mesh) and modified with carboxylated carbon nanotubes | R: 98%, q: 46.95 mg/g, dosage: 0.02 g, contact time: 30.45 min, pH 6.37 and initial cadmium concentration: 10.69 mg/L, Langmuir | [50] |

| Ni(II) aqueous solution (20–200 mg/L) | AV leaf residue: steam-heated (40–50 Ka, 20–30 min), washed with H2O, dried (353 K, 24 h), grinded, sieved (100 mesh). The obtained powder mixed with Na2CO3 solution (250 rpm, 12 h), filtered, washed with H2O | q: 28.98 mg/g, 303 K, dosage: 600 mg/L, contact time: 90 min, pH 7. Pseudo-first-order, Langmuir | [51] |

| Th and Ba aqueous solutions (5–200 mg/L) | AV gel dried (333 K), grounded, sieved (<125 μm), treated with H3PO4 (1.5 M), filtered, rinsed with H2O and dried (333 K). | Th: q: 96.2 mg/g, Langmuir Ba: q: 47.62 mg/g, Freundlich | [52] |

| Aqueous solutions (Th and Ba: 5–200 mg/L) | AV gel dried (333 K), grounded, sieved (<125 μm), treated with H3PO4 (1.5 M), filtered, rinsed with H2O and dried (333 K). | Th: q: 170 mg/g, Langmuir Ba: q: 107.5 mg/g, Freundlich | [52] |

| As aqueous solution (43,000 mg/L) | AV leaves | R: 100%, dosage: 30,000 mg/L, contact time: 4 h | [53] |

| Cr(VI) aqueous solution (50 mg/L) | AV treated with H2SO4 | R: 98.66%, q: 58.83 mg/g, dosage 2000 mg/L, pH 1.23, 150 min, 150 rpm, 298 K, Langmuir | [54] |

| Cr(VI) aqueous solution (50 mg/L) | AV HNO3 activated carbon | R: 98.89%, q: 59.88 mg/g, dosage 2000 mg/L, pH 1.21, 90 min, 150 rpm and 298 K, Langmuir | [54] |

| Pb(II) aqueous solution (400–2000 mg/L) | AV leaves dust and cut into small pieces, dried at room temperature (2 weeks), re-dried (323–333 K, 3 h), powdered, sieved (53–74 μm) and treated with H3PO4 (1 M), filtered and washed with distilled water | R: 96.2% when the adsorbent amount was increased from 2000 to 6000 mg/L for an agitation time of 30 min. Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms | [55] |

| Cu(II) aqueous solutions (20,000–70,000 mg/L) | Leaves dried, grinded and sieved (0.2–0.3 μm) | q: 2.27 mg/g, dosage 2 g/L, contact time: 2 h, initial concentration 20,000 mg/L, pH 5, 318 K. Langmuir | [56] |

| Hg(II) aqueous solution (5–15 mg/L) | Ethanolic AV extract reduced using AgNO3 (12 mM) at pH 7, in presence of air (stirred, 330 K, 3 h), then heated (353 K, 2 h) and filtered (0.45 µm). | R: 95% | [57] |

| Pd(II) aqueous solution (5–600 mg/L) | AV shell ash magnetic nanoparticles | q: 47.2 mg/g, dosage: 2000 mg/L, contact time: 15 min, pH 5, 298 K, Freundlich | [58] |

| Textile wastewater (Pb: 0.11 mg/L) | AV gel dried (353 K for 24 h), redried using muffle furnace (673 K for 30 min) | R: 78%, dosage: 20 mg/L, contact time: 60–90 min | [59] |

| Cu (II) aqueous solutions (40–120 mg/L) | Zinc oxide AV nanoparticles: AV gel broth extracts (90%) mixed with zinc nitrate (94,000 mg/L), stirred (120 min) and left at rest (12 h), then dried (1023 K, 1 h) | R > 95%, q: 20.425 mg/L, 298 K, pH 4, 150 min, Langmuir | [60] |

| U(VI) and Cd(II) aqueous solution (1000 mg/L) | Outer layer AV leaves was dried (333 K), grounded, sieved (<125 μm), treated with H3PO4 (1.5) and NaOH (1.5) (24 h at room temperature), filtered, rinsed (H2O) and dried (353 K) | U (VI): q: 370.4 mg/g, dosage: 1.5 g/L, 6 h, pH 4 Cd(II): q: 104.2 mg/g, mg/g, dosage: 1.5 g/L, 6 h, pH 5–6, Langmuir and Freundlich | [61] |

| Aqueous solutions: Ag (I) | AV shell ash supported Ni0.5Zn0.5Fe2O4 magnetic nanoparticles: AV shells were washed, dried (air oven, 353 K, 24 h), ground, sieved, then carbonized (973 K, 2 h), mixed with metal nitrates and dissolved in H2O. The extract mixed with the previous solution and stirring (30 min), evaporated (353 K), ground and calcined (823 K, 2 h). | R: 98.3%, q: 243.90 mg/g, dosage: 4000 mg/L, 30 min, pH 5, initial concentration: 100 mg/L Langmuir and Freundlich | [62] |

| Aqueous solution of malachite green (50–250 mg/L) | Activated AV stems carbon: carbonized with concentrated sulphuric acid, washed with water and activated around (1273 K, 6 h) | q: 334.61 mg/g, 303 K, 50 min, pH 6.5, Langmuir | [63] |

| Aqueous solution of methylene blue (4000 mg/L) | Reduced graphene oxide using AV | R: 98%, dosage 20 mg, 298 K,150 rpm, pseudo second order | [64] |

| Aqueous solution of methylene blue (1000 mg/L) | Outer layer of AV leaves dried (353 K, overnight), crushed, and sieved (<180 μm) | q: 356 mg/g, 300 K Langmuir | [65] |

| Aqueous solution of reactive red RR198 and reactive blue RB19 (10–160 mg/L) | AV leaves dried (378 K, 10 h), ash preparation (573 K, 2 h), sieved (149–74 μm) | RR-198: R: 80%, q: 80.152 mg/g RB-19: R: 90%, q: 88.452 mg/g pH 3, 20 min, 308 K Freundlich | [66] |

| Aqueous solution of Aqueous solution of reactive violet (RV8) and congo red (CR) (5.0–40 mg/L) | AV leaves washed (H2O and ethanol), dried (1 h), powdered, sieved (200 mesh), mixed with CuCl2 and Mg powder (stirred 60 min), filtered, washed (H2O and ethanol), dried (323 K, 1 h), grounded and sieved (200 mesh) | CR: q: 36.90 mg/g RV8: q: 25.19 mg/g dosage: 100 mg/L, pH 5.5, 30 min, initial concentration: 10 mg/L. Langmuir and Freundlich | [67] |

| Aqueous solution of congo red (1000 mg/L) | AV leaves dried, boiled (in H2O), extract mixed with copper sulphate and separation of CuO nanoparticles | Q: 1.1 mg/g, dosage: 5 mg/g, contact time: 10 min, pH 2, Langmuir | [68] |

| Synthesized wastewater (Titan Yellow: 10,000–100,000 mg/L) | Air-dried AV: AV leaves washed, cut into small pieces, air dried, dried in (323–325 K for 2 h), ground, and sieved (1 mm mesh) | R: 79.44%, q: 55.25 mg/g, dosage: 200 mg/50 mL, pH 9, contact time: 30 min, and initial concentration: 100,000 mg/L, Langmuir | [69] |

| Synthesized wastewater (Titan Yellow: 10,000–100,000 mg/L) | Thermally treated AV: air-dried AV treated at 573–773 K (1 h) | R: 31.08–70.85%, q: 4.662–10.63 mg/g, dosage: 4000 mg/L, pH 9, contact time: 30 min, and initial concentration: 100,000 mg/L | [69] |

| Synthesized wastewater: aniline and methyl orange (MO) (20–100 mg/L) | AV leaves wastes-based sulfuric acid modified activated carbon: AV gel washed (H2O), dried (423 K, 24 h), crushed (30–60 μm), carbonization (823 K, 20 min), H2SO4 (0.1) treatment (12 h), filtered, washed (H2O), dried (423 K, 12 h), crushed and sieved (40-mesh) | aniline: q: 185.18 mg/g MO: q: 196.07 mg/g, dosage: 1000 mg/L, contact time: 60 min, pH 3, 300 K Freundlich | [70] |

| Solution of phenol (0.1–64 mg/L) | AV leaves dried (378 K, 3h), burned (973 K, 1 h), milled, converted to nanoscale (stearic acid 3%) | R > 96%, q: 71.73 mg/g, dosage: 80 mg/L, initial concentration: 32 mg/L, contact time: 60 min, 328 K), pH 7, Freundlich and Langmuir | [71] |

| Adsorbents | Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Ni(II) | ||

| Steam-heated AV leaves (Na2CO3 treatment) | 28.98 | [51] |

| Imerata cylindrical (H2SO4 treatment) | 19.13 | [72] |

| Oak sawdust (HCl treatment) | 3.37 | [73] |

| Dalbergia sissoo (NaOH treatment) | 10.47 | [74] |

| Cu(II) | ||

| Dried AV leaves | 2.27 | [56] |

| Tobacco leaves | 17.182 | [75] |

| Tectona grandis L.f. leaves | 15.43 | [76] |

| Ricinus communis leaves | 127.27 | [77] |

| Cd(II) | ||

| Outer layer of AV leaves (treatment with H3PO4 and NaOH) | 104.2 | [61] |

| Sesame waste | 84.74 | [78] |

| Ficus religiosa leaves | 27.14 | [79] |

| Cr(VI) | ||

| AV leaves (treatment with HNO3 activated carbon) | 59.88 | [54] |

| Melaleuca diosmifolia leaves | 62.5 | [80] |

| Ficus auriculata leaves | 6.8 | [81] |

| Adsorbent Based Materials | Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Methylene blue | ||

| Dried outer layer of AV leaves | 356 | [65] |

| Cactus (fruit peels treated with H3PO4) | 416 | [82] |

| Cactus (pear seed cake treated with H3PO4) | 260 | [85] |

| Cactus cladodes | 3.44 | [86] |

| Cactus fruit peel | 222 | [87] |

| Black stone cherries | 321.75 | [88] |

| Walnut shell | 315 | [89] |

| Hazelnut husks | 204 | [90] |

| Wood apple rind | 40 | [91] |

| Methyl orange | ||

| AV gel (dried and treated with H2SO4) | 196.07 | [70] |

| Untreated corn leaves | 675.6 | [92] |

| Corn leaves (treated with HCl) | 4.54 | [92] |

| Sugar scum | 15.24 | [85] |

| Cork powder | 16.66 | [93] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Katubi, K.M.; Amari, A.; Harharah, H.N.; Eldirderi, M.M.; Tahoon, M.A.; Ben Rebah, F. Aloe vera as Promising Material for Water Treatment: A Review. Processes 2021, 9, 782. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9050782

Katubi KM, Amari A, Harharah HN, Eldirderi MM, Tahoon MA, Ben Rebah F. Aloe vera as Promising Material for Water Treatment: A Review. Processes. 2021; 9(5):782. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9050782

Chicago/Turabian StyleKatubi, Khadijah Mohammedsaleh, Abdelfattah Amari, Hamed N. Harharah, Moutaz M. Eldirderi, Mohamed A. Tahoon, and Faouzi Ben Rebah. 2021. "Aloe vera as Promising Material for Water Treatment: A Review" Processes 9, no. 5: 782. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9050782

APA StyleKatubi, K. M., Amari, A., Harharah, H. N., Eldirderi, M. M., Tahoon, M. A., & Ben Rebah, F. (2021). Aloe vera as Promising Material for Water Treatment: A Review. Processes, 9(5), 782. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9050782