Enterprise-Based Participatory Action Research in the Development of a Basic Occupational Health Service Model in Thailand

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Occupational Health Service Model

2.2. Development of Occupational Health Services at the National Level

2.3. Development of Occupational Health Services in Thailand

2.4. Occupational Health Professionals

- Occupational health physicians: management activities for employees, including preplacement medical examination, medical surveillance, medical removal, return to work, follow-up, investigation of occupational poisoning or occupational disease, health promotion, post-employment medical examination, and implementation of an occupational health program in the workplace such as periodic education, providing advice on workplace health and safety issues, helping with audit/evaluation of the occupational health program in the workplace, and maintaining the medical records of employees. Table 2 compares the responsibilities of occupational physicians in the US, Malaysia, and Thailand [21,25,26,27].

- Occupational health nurses: manage cases and provide treatment, follow-up, referrals, and emergency care for occupational injuries and illnesses; counsel workers regarding occupational injuries and illnesses, emotional problems, and substance abuse; promote health and health education; and advise the employer on legal and regulatory compliance, assist in risk management such as collecting health and hazard data, and use the data to prevent injuries and illnesses. According to the Thai Ministry of Health, doctors and nurses must be provided when there are 200 employees or more. For 200 or more employees, one or more nurses (not specific to occupational nurses) are employed during all working hours, and one or more general practitioners (not specific to occupational physicians) are used twice or more per week and 6 h or more per week. For 1000 or more employees, two or more nurses (not specific to occupational nurses) are employed throughout the work period, and one or more general practitioners (not specific to occupational physicians) are used three times or more per week and 12 h or more per week [28]. Table 3 compares the responsibilities of occupational health nurses in the US, Malaysia, and Thailand [21,25,26,27].

- Safety officers: advising the employer on the safety and health measures in the workplace, inspecting the machinery, plant, and equipment, substance, appliances, and processes used in the workplace that may impact employees’ health, and investigating occupational injuries and illnesses. According to the Thai Ministry of Health, safety officers are regulated, whereas other occupational health professionals are not. The number, types, and responsibilities of safety officers vary depending on the type of enterprise and the number of employees. Furthermore, in addition to the duties of the safety officers mentioned above, the safety officers have responsibilities for hazard identification, risk assessment, advice on safety policies, education, and training of employees for safe work, data collection, and analysis to report occupational health injuries and illnesses [29,30]. Table 4 compares the responsibilities of safety officers in the US, Malaysia, and Thailand [21,25,26,27].

2.5. Participatory Action Research

- Technical/scientific/collaborative action research;

- Practical/mutual collaborative/deliberative action research;

- Emancipating/enhancing/critical science/participatory action research.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Participants and Recruitment

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

3.4.1. Situation Analysis

3.4.2. Problem and Cause Analysis and Development of Action Plans

3.5. Participatory Action Research

3.5.1. Phase 1: Preparation Phase

3.5.2. Phase 2: Planning Phase

3.5.3. Phase 3: Action and Observation Phase

3.5.4. Phase 4: Reflection Phase

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Participants’ Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Situational Analysis

4.2.1. Policy

4.2.2. Functions

4.2.3. Organization

4.2.4. Conditions of Operation

4.2.5. General Provisions

4.3. PAR Process to Develop Basic Occupational Health Services

4.3.1. PAR Process of Loop 1

4.3.2. PAR Process of Loop 2

4.4. Four Basic Occupational Health Service Activities Developments

4.4.1. Fit-for-Work Model Development

4.4.2. Return to Work Model Development

4.4.3. Medical Surveillance Model Development

4.4.4. First Aid Room Model Development

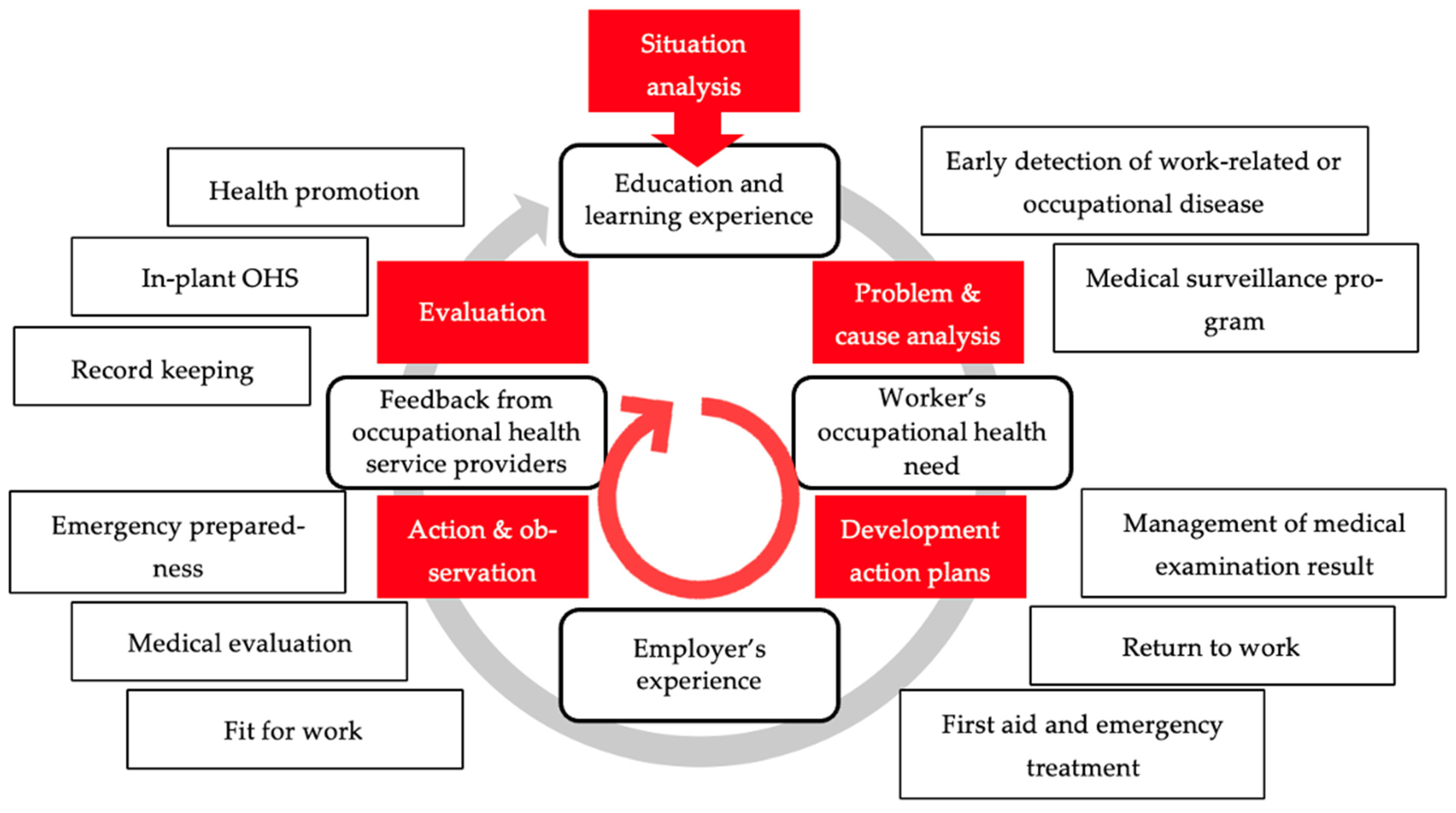

4.5. The in-Plant Basic Occupational Health Service Model

4.6. Multidisciplinary Staff

4.6.1. Occupational Physicians

4.6.2. Occupational Health Nurses

4.6.3. Safety Officers

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Papandrea, D. Enhancing Social Dialogue towards a Culture of Safety and Health: What Have We Learned from the COVID-19 Crisis? International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Workmen’s Compensation Fund, Social Security Office. Occupational Injuries and Illnesses Situation 2017–2021; The Office: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Masekameni, M.D.; Moyo, D.; Khoza, N.; Chamdimba, C. Accessing occupational health services in the Southern African Development Community Region. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Hassard, J.; Leka, S.; Di Tecco, C.; Iavicoli, S. The role of occupational health services in psychosocial risk management and the promotion of mental health and well-being at work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Labour Organization. C161—Occupational Health Services Convention, 1985 (No. 161). Available online: https://kku.world/a3z81 (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Guidotti, T.L. The Occupational health care system. In Occupational Health Services: A Practical Approach; Guidotti, T.L., Arnold, M.S., Lukcso, D.G., Green-McKenzie, J., Bender, J., Rothstein, M.A., Leone, F.H., Hara, K.O., Stecklow, M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen, J. New Concept in Occupational Health Services—BOHS. Available online: https://kku.world/9ydpq (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Good Practice in Occupational Health Services: A Contribution to Workplace Health; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tabibi, R.; Tarahomi, S.; Ebrahimi, S.M.; Valipour, A.-A.; Ghorbani-Kalkhajeh, S.; Tajzadeh, S.; Panahi, D.; Soltani, S.; Dzhsupov, K.O.; Sokooti, M. Basic occupational health services for agricultural workers in the South of Iran. Ann. Glob. Health 2018, 84, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Labour Organization. R171—Occupational Health Services Recommendation, 1985 (No. 171). Available online: https://kku.world/fsijg (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Coppée, G.H. Occupational Health Services and Practice. Available online: https://kku.world/enk1k (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Zodpey, S.; Negandhi, H. Revitalizing basic occupational health services provision for accelerating universal health coverage in 21st century India. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 24, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rantanen, J.; Lehtinen, S.; Valenti, A.; Iavicoli, S. A global survey on occupational health services in selected international commission on occupational health (ICOH) member countries. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siriruttanapruk, S. Integrating Occupational Health Services into Public Health Systems: A Model Developed with Thailand’s Primary Care Units; International Labour Office: Bangkok, Thailand, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Division of Occupational and Environmental Diseases, Department of Disease Control. Audit Criteria and Guidelines: Occupational Health and Environmental Medicine Service Standards for Sub-District Health Promotion Hospitals. Available online: https://kku.world/g1x12 (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- International Labour Organization. Up-to-Date Conventions Not Ratified by Thailand. Available online: https://kku.world/qljf2 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Rantanen, J. Basic Occupational Health Services. Available online: https://kku.world/njusi (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Rantanen, J. Basic Occupational Health Services—Their Structure, Content and Objectives. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2005, 1 (Suppl. S1), 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtinen, S. National Profile of Occupational Health System in Finland; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, D. Asean Occupational Safety and Health: 8th June 2010 Asean National Advocacy Workshop. Available online: https://kku.world/vpa1m (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Ministerial regulations set the standard for employee health checks relating to risk factors B.E. 2563 (A.D. 2020). R. Thai Gov. Gaz. 2020, 137, 30–33.

- Samsuddin, N.; Razali, A.; Rahman, N.A.A.; Yusof, M.Z.; Mahmood, N.A.K.N.; Hair, A.F.A. The proposed future infrastructure model for basic occupational health services in Malaysia. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 26, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dithisawatwe, S.; Yates, J.; Hansittiporn, K.; Khonhan, S.; Choteklang, D.; Srichoom, T.; Polpila, P.; Chomchalo, P.; Pimchainoi, S. Model development of occupational health service in community hospitals. J. Off. DPC 7 Khon Kaen 2018, 25, 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Untimanon, O.; Boonmeephong, K.; Saipang, T.; Laplue, A.; Sukanun, K.; Thongsim, T.; Sirirat, C.; Kanamee, P. Development of friendly occupational health services model for migrant workers using modified Delphi techniques. Dis. Control J. 2022, 48, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. The Occupational Health Professional’s Services and Qualifications: Questions and Answers; U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hartenbaum, N.P.; Baker, B.A.; Levin, J.L.; Saito, K.; Sayeed, Y.; Green-McKenzie, J. ACOEM OEM core competencies: 2021. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, e445–e461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Occupational Safety and Health, Ministry of Human Resource of Malaysia. Guidelines on Occupational Health Services; The Department: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerial regulations on arranging welfare in workplace B.E. 2548 (A.D. 2005). R. Thai Gov. Gaz. 2005, 122, 14–18.

- Ministerial regulation on the prescribing of standard for administration and management of occupational safety, health and environment B.E. 2549 (A.D. 2006). R. Thai Gov. Gaz. 2006, 123, 4–20.

- Ministerial regulations on the provision of safety officers for personnel, agencies or personnel to carry out safety operations B.E. 2565 (A.D. 2022). R. Thai Gov. Gaz. 2022, 139, 9–24.

- Kemmis, S.; McTaggart, R.; Nixon, R. Introducing critical participatory action research. In The Action Research Planner; Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., Eds.; Deakin University: Burwood, VIC, Australia, 1988; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Holter, I.M.; Schwartz-Barcott, D. Action research: What is it? how has it been used and how can it be used in nursing? J. Adv. Nurs. 1993, 18, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhães, L.M.C.A.; da Silva Costa, K.T.; Capistrano, G.N.; Leal, M.D.; de Andrade, F.B. A study on occupational health and safety. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trout, D.B. General principles of medical surveillance: Implications for workers potentially exposed to nanomaterials. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2011, 53 (Suppl. S6), S22–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, D.; Aw, T.-C. Surveillance in occupational health. Occup. Environ. Med. 2003, 60, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jilcha, K.; Kitaw, D. A literature review on global occupational safety and health practice & accidents severity. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2016, 10, 279–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrington, S.; Carr, E.; Stevelink, S.A.M.; Dregan, A.; Woodhead, C.; Das-Munshi, J.; Ashworth, M.; Broadbent, M.; Madan, I.; Hatch, S.L.; et al. Multimorbidity and fit note receipt in working-age adults with long-term health conditions. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 1156–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmage, J.B.; Melhorn, J.M.; Hyman, M.H. How to think about work ability and work restrictions: Risk, capacity, and tolerance. In AMA Guides to the Evaluation of Work Ability and Return to Work; Talmage, J.B., Melhorn, J.M., Hyman, M.H., American Medical Association, Eds.; American Medical Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011; pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Black, C.; Shanmugam, S.; Gray, H. Primary care first contact practitioner’s (FCP) challenges and learning and development needs in providing fitness for work and sickness absence certification: Consensus development. Physiotherapy 2022, 116, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbière, M.; Mazaniello-Chézol, M.; Bastien, M.-F.; Wathieu, E.; Bouchard, R.; Panaccio, A.; Guay, S.; Lecomte, T. Stakeholders’ role and actions in the return-to-work process of workers on sick-leave due to common mental disorders: A scoping review. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2020, 30, 381–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, S.; Dorrington, S.; Parsons, V.; Shah, S.G.S.; Madan, I. The quality of e-fit notes issued in secondary care. Occup. Med. 2020, 70, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Los, F.S.; de Boer, A.G.E.M.; van der Molen, H.F.; Hulshof, C.T.J. The implementation of workers’ health surveil lance by occupational physicians: A survey study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 61, e497–e502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Los, F.S.; van der Molen, H.F.; Hulshof, C.T.J.; de Boer, A.G.E.M. Supporting occupational physicians in the implementation of workers’ health surveillance: Development of an intervention using the behavior change wheel framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safe Work Australia. Code of Practice First Aid in the Workplace; SafeWork NSW: Lisarow, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- A Guide to First Aid in the Workplace; AGPS Publications: Canberra, Australia, 2007.

- United States. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Best Practices Guide: Fundamentals of a Workplace First-Aid Program; U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Health and Safety Executive. First Aid at Work the Health and Safety (First-Aid) Regulations 1981, 3rd ed.; HSE: Norwich, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Occupational Safety and Health (Malaysia). Guidelines on First-Aid in the Workplace; The Department: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, E.S.; Chimedza, I.T.; Mabhele, S.; Romao, P.; Spiegel, J.M.; Zungu, M.; Yassi, A. Empowering health workers to protect their own health: A study of enabling factors and barriers to implementing healthWISE in Mozambique, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, D.; Zungu, M.; Kgalamono, S.; Mwila, C.D. Review of occupational health and safety organization in expanding economies: The case of Southern Africa. Ann. Glob. Health 2015, 81, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, M.A.; Encina, V.; Solis-Soto, M.T.; Parra, M.; Bauleo, M.F.; Meneses, C.; Radon, K. Courses on basic occupational safety and health: A train-the-trainer educational program for rural areas of Latin America. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnavita, N. Medical surveillance, continuous health promotion and a participatory intervention in a small company. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braeckman, L.; Venema, A.; Van Zoelen, S.A.; Hermans, L.; De Ridder, M.; Ergör, A.; Özlü, A.; Van Der Laan, G.; Van Dijk, F. Development and evaluation of a training program on occupational health research and surveillance in Turkey. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 61, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, J.; Carruth, A.; Bui, T.; Perkins, R.; Gilmore, K.; Wickman, A. Experiences in the gulf of mexico: Overcoming obstacles for commercial fishing occupational safety and health research. J. Agromed. 2019, 24, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Tong, R. Development of occupational health culture scale: A study based on miners and construction workers. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 992515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Huang, Y.; Wu, F.; Liu, D.; Wei, C.; Qin, Y. Improving occupational health for health workers in a pilot hospital by application of the HealthWISE international tool: An interview and observation study in China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1010059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, M.; Wolf, A.M.A.; López-Gálvez, N.I.; Griffin, S.C.; Beamer, P.I. Proposing a social ecological approach to address disparities in occupational exposures and health for low-wage and minority workers employed in small businesses. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2021, 31, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbière, M.; Charette-Dussault, É.; Larivière, N. Recognition during the return-to-work process in workers with common mental disorde. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2022, 32, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmlund, L.; Sandman, L.; Hellman, T.; Kwak, L.; Björk Brämberg, E. Ethical aspects of the coordination of return-to-work among employees on sick leave due to common mental disorders: A qualitative study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, T.; Punpeng, T.; Maiyapakdee, C.; Ketsakorn, A.; Fujino, Y.; Hara, K. Survey of the necessary competencies and proficiency of safety officers in Thailand. Ind. Health 2020, 58, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level | Responsible Organizations | Responsible Duties |

|---|---|---|

| National level | MOH/MOL DOH&S DOH | Regulation and policy |

| Intermediate level | Institute of occupational health, Occupational medicine clinic (university/hospital) | Support service, e.g., training, consultation, certification, research, and development |

| Local level | Tertiary referral center In-plant/in-house OHS SOCSO occupational health clinic Public occupational health clinic OHS group practice center Private occupational health clinic Private clinics | Providing occupational health service |

| US | Malaysia | Vietnam |

|---|---|---|

| - Clinical, occupational, and environmental medicine - Law and regulations - Environmental health - Work fitness and disability management - Toxicology - Hazard recognition, evaluation, and control - Disaster preparedness and emergency management - Health and human performance - Public health, surveillance, and disease prevention - Management and administration | - Preplacement examination and medical surveillance - Analysis of occupational diseases and poisoning co-related with risk assessment - Interpretation and explanation of the results of investigations and recommendation of further action - Notification of occupational diseases and poisoning to DOSH and the employer - Conducting occupational health programs - Providing education and advice on health and safety issues - Audit/evaluation of occupational health programs - Maintaining medical records | - Performing preplacement examinations such as fitness for work within 30 days - Performing periodic examinations such as medical surveillance at least yearly - Performing physical examinations during other periods such as the early detection of occupational disease - Performing return-to-work medical assessments when an employee stops working for three days or more |

| US | Malaysia | Thailand |

|---|---|---|

| - Identifying potential hazards and finding ways to prevent, eliminate, minimize, or reduce hazards - Training programs to promote workplace health and safety - Enhancing the accuracy of OSHA record keeping. - Providing screening related to specific chemicals or exposure, including preplacement physical examinations, job placement assessments, periodic inspections, and maintenance of confidential employee health records - Managing work-related illnesses and injuries, emphasizing early recognition and intervention; making recommendations about work restrictions or removal; and following up and monitoring workers as they return - Health promotion programs - Guiding case management of employees with prolonged or complex illnesses and injuries | - Managing cases—treatment, follow-up, referrals, and emergency care for job-related injuries and illnesses - Counseling and intervening in crisis; counseling workers about related illnesses and injuries, substance abuse, and emotional problems - Promoting education programs that encourage workers to take responsibility for their health - Advising employers on legal and regulatory compliance - Assisting in risk management, e.g., gathering and using health and hazard data to prevent injury and illness | - No identification in laws, regulations, or standards |

| US | Malaysia | Thailand |

|---|---|---|

| - Focusing on developing procedures, standards, or systems to control or reduce hazards and exposure detrimental to people, property, and/or the environment | - Advising employers on measures in the interests of the safety and health of persons employed - Inspecting the machinery, plant, equipment, substances, appliances, or process or any description of manual labor used in place of work, that is of such nature liable to cause bodily injury to any person working - Investigating any accident, near-miss accident, dangerous occurrence, occupational poisoning, or occupational diseases | - Following laws, regulations, and guidance - Analyzing possible dangers - Assessing safety risks - Analyzing work plans and projects on safety measures - Inspecting and assessing workplace operations - Training on work safely - Examining and appraising working conditions - Management of occupational safety - Analyzing and investigating causes of accidents, illness, or annoyance at work - Compiling statistical data and analyzing and writing reports on accidents, illness, or annoyance - Education about occupational and environmental disease for employees - Conducting other occupational and safety activities |

| Loops | Phases | Description | Sessions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loop 1 | Preparation |

| 3 |

| Planning |

| 6 | |

| Action and observation |

| 3 | |

| Reflection |

| 3 | |

| Loop 2 | Re-planning |

| 2 |

| Action and observation |

| 3 | |

| Reflection |

| 3 |

| Job/Disease Criteria | Job Title | Disease | ID | Age (Year) | Year of Service (Year) | Sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job | Manager | - | 1 | 45 | 20 | Male |

| Occupational physician | - | 2 | 41 | 7 | Female | |

| Occupational health nurse | - | 3 | 58 | 35 | Female | |

| Occupational health nurse | - | 4 | 56 | 33 | Female | |

| Occupational health nurse | - | 5 | 43 | 20 | Female | |

| Safety officer | - | 6 | 41 | 18 | Male | |

| Safety officer | - | 7 | 35 | 12 | Female | |

| Safety officer | - | 8 | 25 | 2 | Female | |

| Disease | Employee | Accident | 9 | 33 | 10 | Male |

| Employee | Accident | 10 | 49 | 28 | Female | |

| Employee | Anemia | 11 | 46 | 11 | Male | |

| Employee | Anemia | 12 | 49 | 13 | Male | |

| Employee | Asthma | 13 | 39 | 12 | Female | |

| Employee | Clavicle fracture | 14 | 38 | 18 | Male | |

| Employee | Diabetes mellitus | 15 | 45 | 13 | Female | |

| Employee | Diabetes mellitus | 16 | 42 | 14 | Male | |

| Employee | Foot fracture | 17 | 32 | 6 | Male | |

| Employee | Hypertension | 18 | 39 | 8 | Female | |

| Employee | Hypertension | 19 | 44 | 13 | Female | |

| Employee | Hypertension | 20 | 48 | 28 | Female | |

| Employee | Hypertension | 21 | 45 | 28 | Female | |

| Employee | Hypertension | 23 | 41 | 13 | Male | |

| Employee | Kidney disease | 25 | 46 | 13 | Female | |

| Employee | Low back pain | 26 | 34 | 12 | Female | |

| Employee | Low back pain | 27 | 48 | 27 | Female | |

| Employee | Migraine | 28 | 41 | 13 | Male | |

| Employee | Myofascial pain syndrome | 29 | 35 | 7 | Male | |

| Employee | Thyroid disease | 30 | 43 | 18 | Male |

| Problems | Participants | FGDs |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Association between hazards and health effects | Manager |

|

| Employees |

| |

| Employees |

| |

| 2. Indications of OHS | Safety officer |

|

| 3. Lists of medical examination | Sector heads |

|

| Employees |

| |

| Employees |

| |

| 4. Management of medical examination result | Employees |

|

| Employees |

| |

| 5. Attitude to occupational health professionals | Sector heads |

|

| Employees |

| |

| Employees |

| |

| 6. Facilities and documents | Employees |

|

| Employees |

|

| Problems | Participants | FGDs |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Defining the association between work and illnesses | Safety officer |

|

| 2. Identifying the indications of OHS | Safety officer |

|

| Safety officer |

| |

| 3. Completeness of lists of medical examination | Manager |

|

| 4. Clarifying the working process to provide occupational health | Occupational physician |

|

| 5. Identifying duties of occupational health providers | Manager |

|

| Safety officer |

| |

| Safety officer |

| |

| Safety officer |

| |

| 6. Identification of essential facilities and documents | Safety officer |

|

| Problems | Action Plans | Implementation | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Association between hazards and health effects | Defining the association between work and illnesses | 1. OHP walk-through survey. 2. OHP identifies health hazards, significant exposure assessment, health risk assessment, and lists of preplacement and periodic medical examinations in the walk-through survey report. 3. OHP provides a manual of each department’s hazards and health effects. 4. FGDs to improve and assess the completeness of the manual of hazards and health effects in each department. | Components of the manual of the hazards and health effects in each department: 1. Hazards and health effects 2. Health risks assessment 3. Health conditions may be worsened or aggravated 4. Lists of preplacement medical examination 5. Lists of periodic medical examination 6. FFW certificate in each department |

| 2. Indications of OHS | Identifying the indications of OHS | 1. Preparation of related documents before FGDs. 2. FGDs on the objectives of what indications there are in each BOHS. | 1. Indications of fit-for-work 2. Indications of return-to-work 3. Indications of medical surveillance 4. Indications of first aid room |

| 3. Lists of medical examination | Completeness of lists of medical examination | 1. OHP walk-through survey. 2. OHP identifies health hazards, health risk assessments, and lists of preplacement and periodic medical examinations. 3. The researcher prepared the objectives and the interpretation in each list of medical examinations. 4. FGDs to assess the appropriate list of preplacement and periodic medical examinations. | 1. Lists of preplacement medical examination 2. Lists of periodic medical examination |

| 4. Management of medical examination results | Clarifying the working process to provide occupational health | 1. FGDs on the objectives of the working process in each BOHS. | Components of the flowchart: 1. Methods 2. Description 3. Related documents 4. Responsible person 5. Duration |

| 5. Attitude to occupational health professionals | Identifying duties of occupational health providers | 1. Identification duties of occupational health providers in the flowchart and table in each BOHS. | Duties of occupational health professionals |

| 6. Facilities and documents | Identification of essential facilities and documents | 1. The enterprise provided data on the medical unit providing services. 2. Preparation of related documents before FGDs. 3. FGDs on the objectives of essential facilities and documents. | 1. Lists of medication 2. Lists of medical equipment 3. Lists of documents |

| Problems | Action Plans | Implementation | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limitation of the sub-branch | Approval lists of medical examinations by the main branch | 1. The sub-branch enterprise provided a comparison price per person between current and new medical examinations. 2. The sub-branch enterprise provided information on reasons for changing to the new medical examination. 3. The sub-branch enterprise offered the main branch enterprise new medical examinations. | The main branch enterprise approved lists of medical examinations |

| Inconvenience of the facility | Return to work in the enterprise | 1. The safety officers offered the occupational physicians the opportunity to assess RTW in the enterprise. 2. The occupational physician accepted the offer to complete the assessment of RTW in the enterprise. 3. Safety officers grouped the indicated workers and appointed occupational physicians to assess RTW in the enterprise. | The occupational physician assessed RTW in the enterprise |

| Incompleteness of documents | Completeness of referral forms | 1. Safety officers consulted occupational physicians to suggest additional patient data before going to the occupational physician for an improvement referral form. 2. The occupational physicians suggested additional patient data. 3. The safety officers improved the referral form following the suggestions of the occupational physician. | Development of referral forms |

| Component | Old Activities | PAR | Justifications | New Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | New workers | Problem analysis | Worker’s occupational health need The workers did not undergo medical examinations after work adaptations | 1. New worker 2. Job transfer |

| Medical evaluation | Same medical examination despite the different department | Problem analysis | Employer’s experience The managers want to know contraindicated medical conditions in each department, particularly for highly sensitive jobs | 1. New preplacement evaluation, specifically each department, by the occupational physician 2. Preplacement medical evaluation for heat and hot environments form |

| Medical certificate | General medical certificate | Development of action plans | Support procedure Providing additional documents for the medical evaluation | Fit-for-work certificate form in each department |

| Occupational physician | Not-fit-for-work assessment by the occupational physician before working | Problem analysis | Employer’s experience In high-risk jobs, the managers experienced workers being ill while working | The occupational physician assesses the fitness to work |

| Result | No results after medical assessment | Problem analysis | Employer’s experience In high-risk jobs, the managers experienced workers being ill while working | The results of the medical evaluation were divided into fit and unfit |

| Component | Old Activities | PAR | Justifications | New Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | Employees on sick leave ≥ 3 days | Problem analysis | Education and learning experience Awareness of conditions should be assessed by RTW | 1. Chronic disease with medical restrictions such as heart disease, lung disease, and brain disease 2. Hospital admission or after surgery 3. Frequent sick leave 4. Sick leave ≥ 3 days |

| Occupational physician | No return-to-work assessment | Problem analysis | Worker’s occupational health needs No RTW assessment after illness. The workers desired reassurance from doctors or nurses that their health, fit-for-work status, and their work would not affect their health | The occupational physician assesses the return-to-work employee who has identified an indication |

| Return to work form | No return-to-work form | Development of action plans | Worker’s occupational health needs Providing additional documents convenient for medical evaluation | Return-to-work form |

| Result | No management after the return-to-work assessment | Problem analysis | Worker’s occupational health needs No RTW assessment after illness. The workers desired reassurance from doctors or nurses that their health, fit-for-work status, and their work would not affect their health | Result: fit, unfit, fit with restriction, and fit with limitation |

| Place | The occupational physician assessed the return-to-work status in the hospital | Problem analysis II | Feedback from occupational health service providers The safety officers offered the occupational physicians the opportunity to assess RTW in the enterprise | The occupational physician assessed the return-to-work status in the enterprise |

| Referral form | Incompleteness of the referral form | Problem analysis II | Feedback from occupational health service providers The occupational physicians explained that the RTW problem was due to the incompleteness of the referral form. | The safety officers improved the referral form following the suggestions of the occupational physician |

| Component | Old Activities | PAR | Justifications | New Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design a medical surveillance program | No improvement in periodic medical evaluation | Problem analysis | Worker’s occupational health needs The periodic medical evaluation was not appropriate for their jobs | Occupational physician 1. Walk-through survey (1) 2. Identify hazard (2) 3. Bring measurements (3) 4. Significant exposure and health risk assessment (4) 5. Design a medical surveillance program (5) |

| Medical surveillance program (6) | Medical surveillance program | Problem analysis | Education and learning experience Workers suspected their illnesses were caused by work or not and how hazards in their work affect their health and aggravate their illnesses | 1. New medical surveillance program: - History taking - Physical examination - BEI of exposure - BEI of effect 2. Manual of the hazards and health effects in each department: - Hazards and health effects- Health conditions may be worsened or aggravated |

| Medical examinations | No preplacement and more frequent examination | Problem analysis | Employer’s experience The managers would like to know the contraindications of medical conditions in each department, specifically highly sensitive jobs | - New preplacement evaluation including baseline specifically for each department by the occupational physician |

| Provide test results to employees (7) | Provide in information in medical record books | Problem analysis | Worker’s occupational health needs 1. The workers suspected an association between their abnormal medical examination results and their jobs 2. The workers did not know the meaning of my medical examination results | Occupational physicians and nurses inform workers of their medical examination results with interpretation and management |

| Management of the results of medical surveillance (9) | Re-evaluate the work environment following the medical examination results | Problem analysis | Worker’s occupational health needs The workers did not know how to manage their medical examination results | 1. The occupational physician is responsible for reconfirming, diagnosing, and treating workers with abnormal results. 2. Safety officers re-evaluate the work environment (11) |

| Component | Old Activities | PAR | Justifications | New Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment of emergency condition | -No assessment severity in the first aid room -No identified conditions for referral to hospital | Problem analysis | Worker’s occupational health needs What conditions should you go to hospital? | -Assess the emergency condition -Triage system in the first aid room -Conditions for referral to hospital |

| Assessment of clinical improvement | No clinical assessment after treatment | Problem analysis | Worker’s occupational health needs Workers came back to work despite no clinical improvement after receiving medical treatment | After the workers suffered illnesses, the nurse was responsible for assessing their clinical improvement after treatment |

| Emergency plans | No emergency plans | Development of action plans | Employer’s experience Managers need workers who can provide life support in emergencies | Basic life support training program |

| Health promotion | No health promotion program | Problem analysis | Worker’s occupational health needs Management of abnormal medical examination results | Health promotion program for hypertension |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Passaranon, K.; Chaiear, N.; Duangjumphol, N.; Siviroj, P. Enterprise-Based Participatory Action Research in the Development of a Basic Occupational Health Service Model in Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085538

Passaranon K, Chaiear N, Duangjumphol N, Siviroj P. Enterprise-Based Participatory Action Research in the Development of a Basic Occupational Health Service Model in Thailand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(8):5538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085538

Chicago/Turabian StylePassaranon, Kankamol, Naesinee Chaiear, Napak Duangjumphol, and Penprapa Siviroj. 2023. "Enterprise-Based Participatory Action Research in the Development of a Basic Occupational Health Service Model in Thailand" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 8: 5538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085538

APA StylePassaranon, K., Chaiear, N., Duangjumphol, N., & Siviroj, P. (2023). Enterprise-Based Participatory Action Research in the Development of a Basic Occupational Health Service Model in Thailand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(8), 5538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085538