Abstract

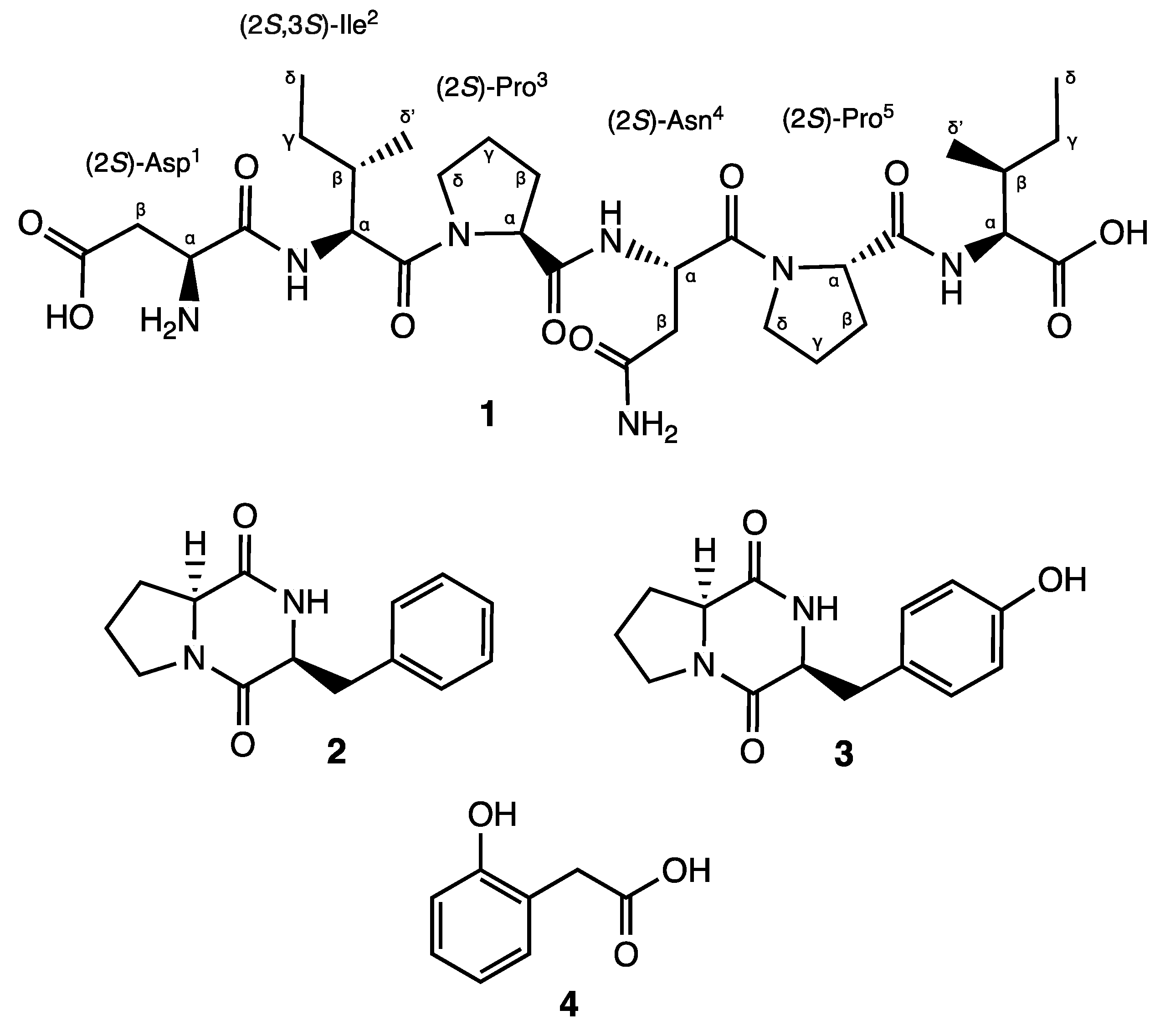

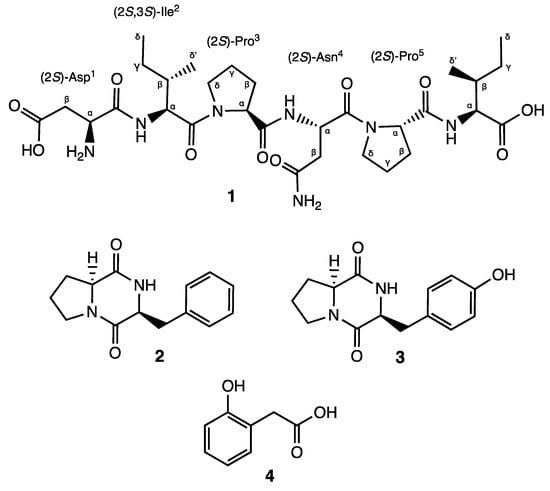

A high proteolytic-resistant hexapeptide (αs1-CN 181–186) (1) along with two known 2,5-diketopiperazines, namely cyclo-(L-Pro-L-Phe) (2) and cyclo-(L-Pro-L-Tyr) (3), as well as the carboxylic acid 2-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (4), were isolated from the actinomycete strain CA287887. The morphological 16S rRNA gene sequence and phylogenetic data of the strain exhibited high similarity with members of the genus Actinomycetospora. The structure of 1 was thoroughly investigated for the first time through the extensive use of 1D and 2D NMR experiments while its absolute configuration was determined by Marfey’s analysis. The anti-tyrosinase effects of the aforementioned compounds were investigated in vitro using kojic acid as the positive control (IC50 14.07 μΜ). Compound 3 exhibited the highest activity (IC50 28.69 μΜ), followed by compound 4 (IC50 98.29 μΜ). Compound 1 was further evaluated for cytotoxicity against HepG2, A2058, A549, and MiaPaca-2 cell lines. At all the tested concentrations (0.01–200 μg/mL), no cytotoxic effect was observed.

1. Introduction

The genus Actinomycetospora, belonging to the family Pseudonocardiacae, was first proposed in 2008 by Jiang et al. [1]. Most of the Actinomycetospora species have been isolated from soil or marine environments, while a few of them have been reported from lichen samples or as endophytes [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Although many different species have been described, their chemical content remains practically unknown. In fact, three thiazole derivatives are the only reported metabolites isolated from Actinomycetospora spp. [6]. In recent years, in-depth research has focused on the diversity of endophytic actinomycetes and their ability to produce a wide range of bioactive secondary metabolites, characterized mainly as alkaloids, flavonoids, steroids, terpenoids, phenolics, quinones, and peptides, as well as on their applications in medicine, agriculture, and industry [3,5,7,8]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have been conducted yet regarding the potential of endophytic actinomycetes to produce metabolites that could be used as skin-whitening agents by inhibiting tyrosinase, the key enzyme of melanin synthesis [9]. Within our screening program aimed at discovering bioactive natural products from microorganisms of global biodiversity with potential cosmeceutical applications, the fermentation extract of Actinomycetospora sp. CA-287887 strain cultivated in the medium M016 was selected for further investigation, due to its major impact on tyrosinase enzyme. The tyrosinase inhibition was observed both in cell-free (34.72 ± 8.46% tested at 0.02 × WBE (whole broth equivalent)) and cell-based assays (70 ± 3.51% tested at 0.02 × WBE, with statistical significance of p < 0.01 vs. cells treated with the vehicle). Herein, we report for the first time the NMR assignments and the absolute configuration of the high proteolytic-resistant hexapeptide, αs1-CN 181–186 (1) (Figure 1), along with the isolation of three known compounds (2–4) (Figure 1) that demonstrated moderate-to-strong tyrosinase inhibitory activity.

Figure 1.

Structures of compounds 1–4.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Experimental Procedures

IR spectra were recorded using a JASCO FT/IR-4100 spectrometer (JASCO Corporation) equipped with a PIKE MIRacleTM single-reflection ATR accessory. One-dimensional (1H and 13C) and two-dimensional (HSQC, COSY, HMBC, NOESY, TOCSY, 1H-15N HMBC, and 1H-15N HSQC) NMR spectra were obtained at 500 MHz, using a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz spectrometer equipped with a low-volume 1.7 mm inverse detection microcryoprobe (Bruker Biospin, Fällanden, Switzerland). Standard pulse sequences and phase cycling from Bruker catalogue were used for all 1D and 2D NMR experiments and the data points, number of scans, and number of increments were adjusted based on sample concentrations. NMR chemical shifts were listed in δ-scale and referenced by the residual signal of the solvent (DMSO-d6, 99.80%, δH 2.5 ppm, δC 39.52 ppm for 1; CD3OD, δH 3.31 and δC 49.0 ppm for 2–4). HRESIMS and LC-UV-MS data were measured using a Bruker maXis QTOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics GmbH, Bremen, Germany) coupled to an Agilent 1200 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) and on an Agilent 1100 single-quadrupole LC-MS system (Santa Clara, CA, USA), as previously described [10]. Preparative HPLC was carried out using a Gilson 322 System (Gilson Technologies, Middleton WI, USA) with an Xbridge™ C18 column (19 × 250 mm, 5 μm) at a flow rate of 20 mL/min. The same system was used for semipreparative HPLC employing an Xbridge™ C18 column (10 × 150 mm, 5 μm) at a flow rate of 2 mL/min. Solvent evaporation was conducted using a vacuum rotatory evaporator (Rotavapor R-3000r, Buchi, Postfach, Switzerland). The acetone used for extraction and the solvents used for isolation were of analytical and HPLC grade, respectively.

2.2. Isolation and Identification of the Strain CA-287887

2.2.1. Microbial Source

The producing strain CA-287887 is an endophyte isolated from the aerial part of a specimen of the plant Genista umbellata, collected in Almerimar (Almería, Spain). The original colony was isolated from YECD agar medium (yeast extract-casein hydrolysate agar) [11], with the addition of nalidixic acid (20 µg/mL) and purified on yeast Extract Malt Extract Glucose medium (ISP2) prior to being stored as frozen agar plugs in 10% glycerol in MEDINA’s culture collection.

2.2.2. DNA Extraction and 16S rDNA Sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted and purified as described previously [12] from the strain cultured in ATCC-2 liquid medium, which contained 0.5% yeast extract (Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), 0.3% beef extract (Difco), 0.5% peptone (Difco), 0.1% dextrose (Difco), 0.2% potato starch (Panreac, Barcelona, Spain), 0.1% CaCO3 (E. Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and 0.5% NZ amine E (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). DNA samples were used as templates for Taq polymerase in PCR reactions. The primers fD1 and 1100r were employed to amplify the 16S ribosomal RNA gene of the strain [12]. The reactions were carried out in a 50 µL final volume containing 0.4 µM of each primer, 0.2 mM of each of the four deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA), 5 µL of extracted DNA, and 1U of Taq polymerase (Appligene, Watford, UK) with its recommended reaction buffer. PCR amplifications were performed in a Peltier Thermal Cycler PTC-200 using the following cycling conditions: 5 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 52 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C, with a final extension of 10 min at 72 °C. The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 2% (w/v) pre-cast agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide (E-gel 2%, 48 wells, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The PCR products were sent to Secugen (http://www.secugen.es/, accessed on 15 March 2017) for sequencing, purified, and used as templates for sequencing reactions with primers fD1 and 1100r [12]. Sequencing was performed using the ABI PRISM DYE Terminator Cycle sequencing kit, and the fragments were resolved on an ABI3130 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The partial sequences were assembled and edited using the Assembler contig editor of Bionumerics (ver 6.6) software (Applied Maths NV, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium).

2.2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

The almost-complete 16S rRNA gene sequence (1361 nucleotides) of strain CA-287887 was compared with sequences available in public databases and on the EzBiocloud server [13,14]. The strain showed the highest similarity (99.56%) with Actinomycetospora atypica NEAU-st4T (KC412867) by performing sequence similarity searches and homology analysis using EzBiocloud and GenBank.

Phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analyses were performed using MEGA version X [15]. Multiple alignment was carried out using CLUSTALX [16], integrated in the software. The phylogenetic analysis, based on the Neighbour-Joining method [17] using matrix pairwise comparisons of sequences corrected with the Jukes and Cantor algorithm [18], demonstrates that the strain is highly related to the type strain Actinomycetospora atypica NEAU-st4T and this relatedness is further reinforced in the analysis by the bootstrap value (76) (Figure S17).

The morphological characteristics, 16S rRNA gene sequence, and phylogenetic data suggested that strain CA-287887 was representative of members of the genus Actinomycetospora and the strain was referred to as Actinomycetospora sp. CA-287887.

2.3. Scale-Up Fermentation, Extraction, and Isolation of Compounds

To scale-up the microfermentation to 2 L, 0.5 mL of the frozen inoculum stocks was added into a sterile colony tube (150 × 24 mm with a cover slip inside) filled with 10 mL of ATCC-2 seed medium (starch 20 g, dextrose 10 g, NZ Amine type E 5 g, Difco Beef extract 3 g, Bacto Peptone 5 g, yeast extract 5 g, CaCO3 1 g, distilled H2O 1 L) and incubated in an orbital Kühner shaker for 5 days at 28 °C, 70% humidity, for 225 rpm. After the end of the incubation, 2.5 mL was transferred into two 250 mL baffled-flasks filled with 50 mL of seed medium and were incubated following the same conditions. A total of 7.5 mL of the second seed medium was transferred to twenty 500 mL flasks containing 150 mL of the fermentation medium M016 [19] and incubated for 7 days, under the same conditions.

The extraction of the scale-up fermentation broth (2 L) was performed with acetone (2 L) under continuous shaking at 220 rpm for 1 h, followed by centrifugation. The remaining mixture (ca. 4 L) was concentrated to ca. 2 L under a nitrogen flow. The solution was loaded, keeping the flow-through (aqueous fraction, AQ) on a column packed with SP-207ss reversed-phase resin (brominated styrenic polymer, 65 g) previously equilibrated with water, with continuous 1:1 water dilution. The loaded column was additionally washed with water (2 L) and eluted at 10 mL min−1 on an automatic flash-chromatography system (CombiFlash Rf400, Teledyne ISCO Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) using a linear gradient from 5% to 100% acetone in water (in 30 min) with a final 100% acetone step (for 20 min) collecting 32 fractions of 20 mL. A centrifugal evaporator was used to concentrate the fractions to dryness, and afterwards all of them were tested for their tyrosinase inhibitory activity and analyzed by HRMS. Fractions 12, 13, 14, and AQ exhibited tyrosinase inhibitory effect and thus they were forwarded to a detailed chemical investigation.

The purification of fraction 12, containing mainly compound 1, was performed by preparative HPLC (UV detection at 210 nm) using a linear gradient of H2O−CH3CN from 5% to 35% CH3CN over 36 min, followed by a gradient to 100% CH3CN in 2 min to obtain 86 fractions that were collected every 0.5 min. Fraction 44 (13.2 mg, eluted at 22.2 min), that contained compound 1, was further purified by semipreparative HPLC (UV detection at 210 nm) using a linear gradient of H2O−CH3CN from 5% to 60% CH3CN over 20 min, followed by a gradient to 100% CH3CN in 2 min, to yield compound 1 (1.7 mg) with a retention time of 10.4 min.

Compounds 2, 3, and 4 were obtained from fractions 13, 14, and AQ, respectively. Compound 2 (2.6 mg) was obtained by using semipreparative HPLC (UV detection at 210 nm), using isocratic elution with H2O−CH3CN: 25–75% for 20 min, followed by a gradient to 100% CH3CN in 15 min (retention time of 2: 2.6 min).

Compound 3 (5.6 mg) was obtained by first using a preparative HPLC (UV detection at 210 nm), using a linear gradient from H2O−CH3CN: 95–5% to H2O−CH3CN: 30–70% over 36 min, followed by a gradient to 100% CH3CN in 2 min (elution time of fraction containing 3: 10.1 min). Further purification of the fraction containing 3 was performed by semipreparative HPLC using a linear gradient system from H2O−CH3CN: 95–5% to H2O−CH3CN: 78–22% over 18 min, followed by a gradient to 100% CH3CN in 2 min (retention time of 3: 9.9 min).

Compound 4 (1.2 mg) was eluted at 4.7 min from the AQ fraction, using an isocratic method with H2O−CH3CN: 98–2% for 10 min, followed by a gradient to 100% CH3CN in 6 min (retention time of 4: 4.7 min).

2.4. Marfey’s Analysis

Compound 1 (0.5 mg, 0.5 mg/mL) was treated with 6 N HCl in a sealed vial at 110 °C for 16 h. After concentration of the hydrolyzed sample to dryness, it was reconstituted in H2O (100 μL) and 50 μL of the sample was treated with 150 μL of 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl-5-L-valinamide (L-FDVA) (1% in acetone) and 20 μL of 1 M NaHCO3 in a sealed vial at 40 °C for 1 h. The neutralization of the reaction mixture was performed with 30 μL of 1 N HCl [20]. For the LC-MS analysis, a 10 μL aliquot was diluted with 40 μL of CH3CN. For each standard amino acid, the same process was followed starting with a stock solution of 50 mM. The resulting solutions were analyzed by LC-MS using a Zorbax SB-C8 column (21 × 300 mm, 3.5 μm) and the solvents used were A (10% CH3CN, 90% H2O, 1.3 mM TFA, 1.3 mM ammonium formiate) and B (90% CH3CN, 10% H2O, 1.3 mM TFA, 1.3 mM ammonium formiate)/90%). For the hydrolysate of 1 and amino acids Ile and allo-Ile, an isocratic system of 10% B for 2 min, followed by a linear gradient to 60% B in 33 min at a flow of 1 mL/min, was used. For the hydrolysate of 1 and amino acids Pro and Asp, an isocratic system of 10% B for 2 min, followed by a linear gradient to 20% B in 33 min at a flow of 1 mL/min, was used. The hydrolysate of 1 contained L-Ile (12.76 min), L-Pro (13.27 min) and L-Asp (6.75 min). The retention time of the L-FDVA derivatives of the authentic amino acids were as follows: L-Ile (12.77 min), D-Ile (17.83 min), L-Allo-Ile (12.55 min), D-Allo-Ile (17.66 min), L-Pro (13.21 min), D-Pro (18.94 min), L-Asp (6.52 min) and D-Asp (9.08 min).

2.5. Biological Evaluation

2.5.1. Tyrosinase Inhibitory Assay

Enzymatic Assay

The inhibitory effect of the tested extracts and compounds on tyrosinase-catalyzed oxidation of L-DOPA to dopachrome was assessed using mushroom tyrosinase, a lyophilized powder with an activity of ≥1000 units/mg solid (EC number: 1.14.18.1) [21].

Cell-Based Assays

Cell lines and cell culture conditions

Mouse skin melanoma cells (B16-F10) were sourced from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC). These cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS and 2 mM glutamine. They were kept in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Subculturing was performed using a trypsin/EDTA solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Tyrosinase activity

Mouse melanocytes B16F10 were planted in 60 mm dishes. After 24 h of treatment with 1 μg/mL or 10 μg/mL for each extract, cells were lysed with 0.2% Nonidet P-40 buffer. L-DOPA (Sigma Chemical) was used as a substrate for the tyrosinase activity assay. A total of 20 μg of proteins from each sample (diluted in 100 μL of phosphate buffer) was placed in a 96-well micro plate. L-DOPA (final concentration 5 mM) was added to each sample. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. The absorbance was measured at 475 nm. Each sample was prepared in triplicate. The percentage of relative tyrosinase activity was calculated as follows: % Activity = [(A1 − Bl)/ (A0 − Bl)] × 100, where A0 = control absorbance, Bl = blank absorbance (L-DOPA only), and A1 = sample absorbance.

2.5.2. Cytotoxicity

Cytotoxicity was evaluated using the MTT assay on HepG2, A2058, A549, MCF-7, and MIA PaCa-2 cell lines, while the HOECHST assay was employed for the CCD25sk cell line, following a previously established procedure [12].

3. Results and Discussion

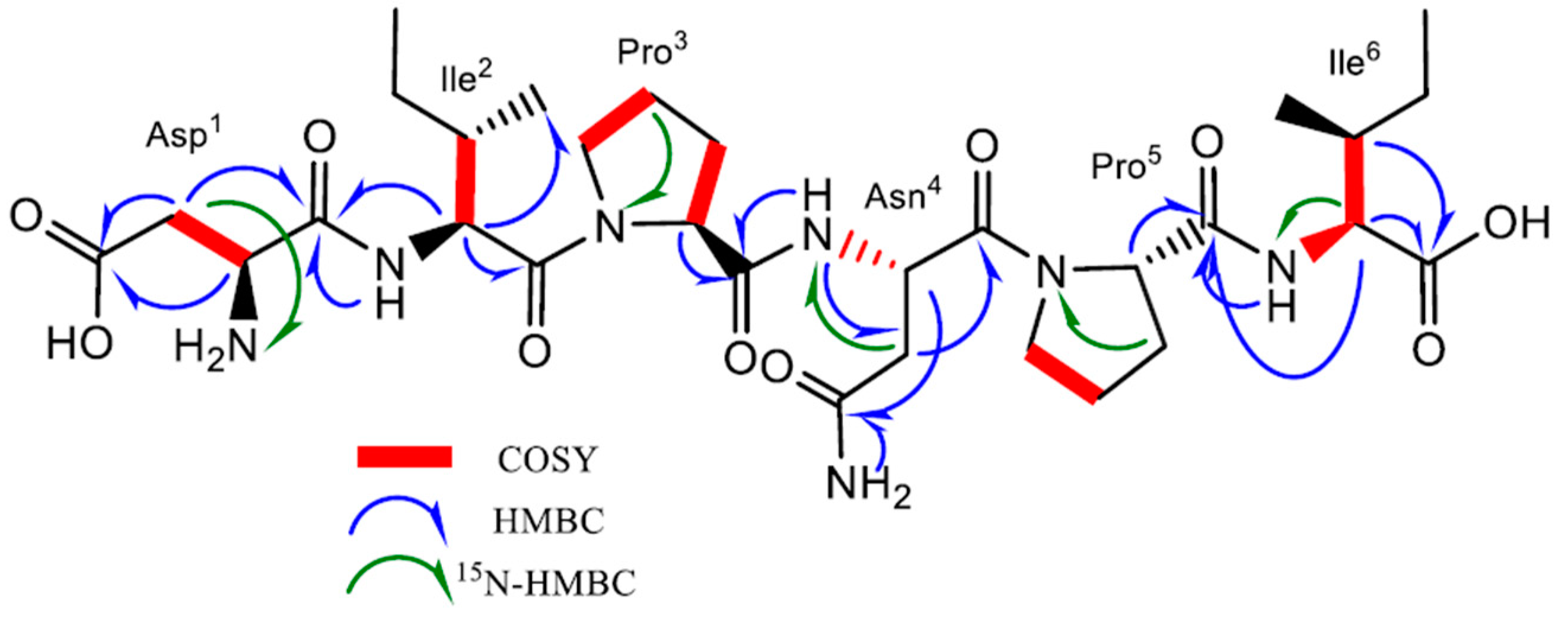

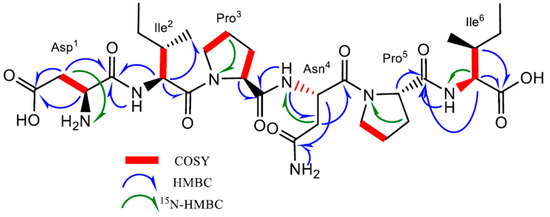

Compound 1 was obtained as a brownish solid. On the basis of 1D- and 2D-Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) experiments, along with High-Resolution Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectroscopy (HRESIMS) data, its molecular formula, implying ten degrees of unsaturation, was deduced to be C30H49N7O10 (m/z 666.3454 [M-H]−, m/z 668.3585 [M + H]+). The infrared spectroscopy (IR) spectrum of compound 1 showed characteristic absorption bands for secondary amines (3286 cm−1) and amide carbonyls (1632 cm−1), while the absence of any ultraviolet (UV) absorption above 201 nm excluded the presence of conjugated π (pi) bond systems. Analysis of the 13C NMR spectrum revealed 30 signals. On the basis of a Distortionless Enhancement by Polarization Transfer (DEPT) and of a Heteronuclear Single-Quantum Correlation Spectroscopy (HSQC)-DEPT experiment, the aforementioned signals were assigned to eight methine, ten methylene, four methyl, and eight quaternary carbons, while the analysis of the 15N-HSQC and 15N-Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation (15N-HMBC) spectra revealed additional nitrogen signals relative to one primary, three secondary, and two tertiary amide groups (Figure 2). In the ¹H-¹H Correlation Spectroscopy (COSY) experiment, NH signals of each secondary amide showed cross-peaks with proton resonances at δH 4.07, 4.34, and 4.74 in the 1H NMR spectrum (Table 1), which are characteristic of the α-methine protons of amino acidic residues. The analysis of the different spin systems by 2D-Total Correlation Spectroscopy (2D-TOCSY) resolved and assigned the α-methine protons at δH 4.07 and 4.34 to two isoleucine residues (Ile2 and Ile6), while the HMBC correlation of the α-methine proton at δH 4.74 with the carbonyl of a primary amide group at δC 171.8 suggested the presence of Asparagine (Asn4). In addition, the HMBC correlations of Ile2 and Ile6 Hα protons with their respective Cγ, Cδ’ protons, as well as the hetero-correlations between the primary amide protons at δH 7.40 and 6.88 and the carbonyl carbon at δC 171.8 of the side chain of Asn4, further confirmed the above hypothesis.

Figure 2.

Key 1H-1H COSY, HMBC, and 15N-HMBC correlations of compound 1.

Table 1.

NMR spectroscopic data of compound 1 (in DMSO-d6).

Three additional α-methine protons at δH 3.75, 4.31, and 4.38 were identified in the 1HNMR spectrum. However, unlike the Hα protons of Ile2, Ile6, and of Asn4, they did not show any COSY correlation with amino carbonyl protons. Regarding the downshifted α-protons at δH 4.31 and 4.38, this was clear evidence of an adjacent tertiary amide group instead of a primary amine. Analysis of the HMBC spectrum evidenced the correlation of the α-proton at δH 4.31 and 4.38 with methylene carbons at δC 29.1, 24.2, 47.2, 28.9, 24.4, and 46.6, respectively. The aforementioned chemical shifts in combination with the presence of tertiary amide groups suggested the presence of two proline residues in the molecule (Pro3 and Pro5). Further analysis of COSY and TOCSY spectra confirmed the above findings.

Finally, the upfield shift in the α-methine proton at δH 3.75 in combination with its COSY correlation with methylene β-protons at δH 2.45 and 2.27, which in turn showed 15N HMBC correlations with an aliphatic ammine at δC 32.9, suggested the presence of a N-terminal aminoacidic residue. Further analysis of the HMBC spectrum showed a 2J and 3J long-range correlation between the α- and β-protons and the quaternary carbon at δC 172.6, suggesting an acetyl side chain relative to aspartic acid (Asp1).

The exact sequence was established on the basis of HMBC and Nuclear Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy (NOESY) experiments (Figure S1). The HMBC correlation between the Hα of Ile2 and the carbonyl amide at δC 170.9 of Asp1 confirmed the first two amino acids of the hexapeptide molecule, while the NOESY correlations Hα, Hδ′ (Ile2)/Hδ (Pro3), Hα (Pro3)/NH(Asn4), and Hα (Pro3)/NH(Asn4) in combination with the HMBC correlation Hα(Pro3), NH(Asn4)/CO(Pro3) unambiguously assigned the position of the residues Pro3 and Asn4. Finally, the positions of Pro5 and of Ile6 were defined on the basis of the NOESY correlations between Hα (Asn4)/Hδ (Pro5) and Hα (Pro5)/NH(Ile6) and of the HMBC correlations between Hα, NH (Ile6)/CO(Pro5). Consequently, the presence of the linear peptide N-Asp-Ile-Pro-Asn-Pro-Ile was assumed. Further ESI-MS/MS analysis confirmed our hypothesis. Indeed, it showed characteristic ions at m/z 551.3, 438.2, 324.1, 341.1, 227.1, and 130.9 corresponding to the fragmentation of the five peptide bonds composing the hexapeptide (Figure S2).

The absolute configuration of the amino acid residues was identified through performing Marfey’s analysis [20]. The complete hydrolysis of compound 1 was performed with hydrochloric acid (HCl) 6N followed by the derivatization of the hydrolysate and the D- and L-amino acid standards with L-FDVA, a chiral derivatizing agent that converts amino acid enantiomers into diastereomeric pairs, allowing their separation by reversed-phase HPLC. The absolute configuration of all residues was achieved by comparison of the retention times of the L-FDVA hydrolysate with the L-FDVA derivatized D- and L-amino acid standards. The results from the HPLC comparative analysis indicated an L configuration for Asp, Ile, and Pro. Accordingly, the absolute configuration of compound 1 was elucidated as L-Asp-L-Ile-L-Pro-L-Asn-L-Pro-L-Ile (Figures S17–S19).

Regarding the cis-trans interconversion of proline residues, neither the ¹H-¹⁵N HSQC nor the ¹³C-NMR spectra revealed more than one conformation. In particular, the ¹³C-NMR spectra, where cis and trans forms of proline peptide bonds can be clearly distinguished based on the chemical shifts in the ring-carbon resonances, showed no detectable alternative conformations. This may suggest the presence of a predominant form. Considering that NMR studies of model peptides typically indicate a cis-trans ratio of 1:10 for random-coil polypeptide chains, we may infer that the trans form is predominant. However, it is important to note that the cis-trans interconversion of proline residues is highly sensitive to minor variations in experimental conditions, including temperature, solvent, pH, and other triggering factors [22,23,24].

Compound 1 corresponds to amino acid residues 181–186 of bovine αs1-Casein and it has been reported as a strong growth-stimulating agent for lactic acid bacteria (LAB) with a high resistance to proteolysis, able to survive in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. Growth-promoting activity primarily requires the presence of Glu, His, and Met, along with Leu, Cys, Val, Ile, Trp, Arg, and Tyr. Notably, Compound 1 contains Ile residues, and its supplementation resulted in a 166.7% increase in LAB biomass yield. Furthermore, peptides ranging from four to eight residues have demonstrated stronger growth-stimulating activity for LAB compared to their parent native proteins, larger polypeptides, or even free amino acids. These findings on structure–function relationships suggest that both peptide length and specific amino acid sequences play a crucial role in growth-promoting activity. Beyond this function, casein-derived peptides containing six to seven amino acid residues have been shown to exhibit antihypertensive, antiviral, ACE-inhibitory, antioxidant, opioid agonist, and immunomodulatory activities [25,26,27].

In addition to compound 1, bioassay-guided fractionation led to the isolation of three known compounds, namely cyclo-(L-Pro-L-Phe) (2) [28], cyclo-(L-Pro-L-Tyr) (3) [29], and 2-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (4) [30]. Their structures were established on the basis of NMR and HRMS data and through a comparison of their spectroscopic and physical data with the literature.

All isolated compounds were tested for their ability to inhibit tyrosinase, the key enzyme involved in melanogenesis in both plants and animals. Tyrosinase inhibitors, commonly known as skin-whitening agents, have cosmetic and clinical applications, including brightening skin complexion and treating hyperpigmentary disorders. Over the years, various classes of skin-whitening agents have been identified, primarily including pyrones (e.g., kojic acid), phenolic lactones (e.g., ellagic acid), carboxylic acids (e.g., azelaic acid), teichoic acids (e.g., lipoteichoic acid), and quinones (e.g., arbutin undecylenic acid ester). Kojic acid is currently one of the most potent tyrosinase inhibitors on the market and has been widely used as a skin-depigmenting agent in cosmetics, demonstrating excellent lightening/whitening effects [31]. Among the isolated compounds, compound 3 (IC50 = 28.69 μΜ) exhibited the highest inhibitory activity with an IC50 value comparable to that of the positive control kojic acid (IC50 = 14.07 μΜ). Its potential use as a tyrosinase inhibitor was further supported by its lack of any cytotoxic effect [32,33,34]. Moderate activity was also found for compound 4 (IC50 = 98.29 μΜ) while no inhibitory effect was confirmed for compounds 1 and 2 (IC50 > 300 μM). The inhibitory capacity of compounds 3 and 4 was statistically significant (p < 0.01) vs. control samples. To our knowledge, this is the first report on investigating the anti-tyrosinase effect of compounds 3 and 4 using L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA) as a substrate [35].

During our analysis, we screened compound 1 against a panel of cancer cell lines. No cytotoxic effect against the cancer cell lines HepG2, A2058, A549, and MiaPaca-2 was detected at the highest concentration used. Considering that compound 1 belongs to a class of peptides that are capable of surviving gastrointestinal digestion, the lack of cytotoxicity can be interpreted as a positive outcome in view of its potential therapeutic activities.

Compound ()

Brownish solid; soluble in H2O, MeOH, and DMSO; UV (MeOH) λmax only end absorption detected; IR vmax 3293, 3286, 2965, 1722, 1644, 1632, 1537, 1448, 1314, 1254, 1220, 1024, 953 cm−1; 1H (500 MHz) and 13C (125 MHz) NMR spectral data in DMSO-d6, see Table 1; NMR homo- and hetero-correlations in DMSO-d6, see Table S1; HRESIMS m/z: 668.3605 [M + H]+ (calcd for C30H50N7O10, 668.3619).

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, the strain CA-287887, identified as Actinomycetospora sp., demonstrated the most significant tyrosinase inhibitory activity among other extracts of endophytic actinomycetes. The bio-guided fractionation led to isolation and the proteolytic-resistant hexapeptide αs1-CN 181–186 (1), described for the first time in microbial cultures, along with three known compounds, namely cyclo-(L-Pro-L-Phe) (2), cyclo-(L-Pro-L-Tyr), (3) and 2-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (4). Complete structural elucidation was carried out for compound 1, including NMR and HRMS/MS analyses, along with the establishment of the absolute configuration. A wide cytotoxic screening against a panel of cancer cell lines was also carried out. Regarding the skin-whitening activity, compounds 3 and 4 exhibited the highest inhibitory activity against tyrosinase enzyme with IC50 values of 28.69 and 98.29 μΜ, respectively, explaining the significant whitening effect that the extract demonstrated during the high-throughput screening.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/separations12030057/s1, Figure S1. Key NOESY correlations of compound 1. 3D structure based on MM2 calculations with minimized energy. Figure S2. ESI-MS/MS analysis of compound 1 (negative ion mode). Table S1. Homo and hetero-correlations of compound 1 (in DMSO-d6). Figure S4. 1H-NMR of compound 1 in DMSO-d6. Figure S5. 13C-NMR of compound 1 in DMSO-d6. Figure S6. COSY of compound 1 in DMSO-d6. Figure S7. HSQC of compound 1 in DMSO-d6. Figure S8. HMBC of compound 1 in DMSO-d6. Figure S9. NOESY of compound 1 in DMSO-d6. Figure S10. TOCSY of compound 1 in DMSO-d6. Figure S11. 15N-HMBC of compound 1 in DMSO-d6. Figure S12. 15N-HSQC of compound 1 in DMSO-d6. Figure S13. HRMS-ESI+ of compound 1. Figure S14. MS-MS of compound 1. Figure S15. IR of compound 1. Figure S16. UV of compound 1. Figure S17. ESI+ chromatograms of the hydrolysate of 1 and amino acid Pro. Figure S18. ESI+ chromatograms of the hydrolysate of 1 and amino acid Asp. Figure S19. ESI+ chromatograms of the hydrolysate of 1 and amino acid Ile. Figure S20. Phylogenetic neighbor-joining tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Figure S21. 1H-NMR of compound 2 in MeOD. Figure S22. 1H-NMR of compound 3 in MeOD. Figure S23. 1H-NMR of compound 4 in MeOD.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, K.G., N.T., I.G., J.M., T.A.M. and S.G.; Investigation, K.G., I.G. and F.R.; Methodology, K.G., T.A.M. and F.R.; Writing—original draft, K.G. and N.T.; Writing—review and editing, N.T., I.P.T., O.G. and N.F. Supervision, O.G. and N.F.; Conceptualization, I.P.T., O.G. and N.F.; Funding acquisition, N.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been financially supported by the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (HFRI) and the General Secretariat for Research and Technology (GSRT), under the HFRI PhD Fellowship grant (GA. no. 2369). Part of this work has been supported by the EU in the framework of the MICROSMETICS project (FP7-PEOPLE Industry–Academia Partnerships and Pathways), grant agreement no. 612276.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jiang, Y.; Wiese, J.; Tang, S.-K.; Xu, L.-H.; Imhoff, J.F.; Jiang, C.-L. Actinomycetospora chiangmaiensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a New Member of the Family Pseudonocardiaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamura, H.; Ashizawa, H.; Nakagawa, Y.; Hamada, M.; Ishida, Y.; Otoguro, M.; Tamura, T.; Hayakawa, M. Actinomycetospora iriomotensis sp. nov., a Novel Actinomycete Isolated from a Lichen Sample. J. Antibiot. 2011, 64, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T.; Ishida, Y.; Hamada, M.; Otoguro, M.; Yamamura, H.; Hayakawa, M.; Suzuki, K.-I. Description of Actinomycetospora chibensis sp. nov., Actinomycetospora chlora sp. nov., Actinomycetospora cinnamomea sp. nov., Actinomycetospora corticicola sp. nov., Actinomycetospora lutea sp. nov., Actinomycetospora straminea sp. nov., and Actinomycetospora succinea sp. nov. and Emended Description of the Genus Actinomycetospora. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 61, 1275–1280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Shen, Y.; Li, C.; He, H.; Wang, X.; Xiang, W. Actinomycetospora atypica sp. nov., a Novel Soil Actinomycete and Emended Description of the Genus Actinomycetospora. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2014, 105, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Li, C.; Liu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Xiang, W. Actinomycetospora rhizophila sp. nov., an Actinomycete Isolated from Rhizosphere Soil of a Peace Lily (Spathiphyllum Kochii). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 1520–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, P.; MacMillan, J.B. Thiasporines A–C, Thiazine and Thiazole Derivatives from a Marine-Derived Actinomycetospora chlora. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 548–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakdapetsiri, C.; Ngaemthao, W.; Suriyachadkun, C.; Duangmal, K.; Kitpreechavanich, V. Actinomycetospora endophytica sp. nov., Isolated from Wild Orchid (Podochilus microphyllus Lindl.) in Thailand. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 3017–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewkla, O.; Franco, C.M.M. Actinomycetospora callitridis sp. nov., an Endophytic Actinobacterium Isolated from the Surface-Sterilized Root of an Australian Native Pine Tree. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2019, 112, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillaiyar, T.; Manickam, M.; Namasivayam, V. Skin Whitening Agents: Medicinal Chemistry Perspective of Tyrosinase Inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2017, 32, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, J.; Crespo, G.; González-Menéndez, V.; Pérez-Moreno, G.; Sánchez-Carrasco, P.; Pérez-Victoria, I.; Ruiz-Pérez, L.M.; González-Pacanowska, D.; Vicente, F.; Genilloud, O.; et al. MDN-0104, an Antiplasmodial Betaine Lipid from Heterospora chenopodii. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 2118–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombs, J.T.; Franco, C.M.M. Isolation and Identification of Actinobacteria from Surface-Sterilized Wheat Roots. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 5603–5608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgousaki, K.; Tsafantakis, N.; Gumeni, S.; Gonzalez, I.; Mackenzie, T.A.; Reyes, F.; Lambert, C.; Trougakos, I.P.; Genilloud, O.; Fokialakis, N. Screening for Tyrosinase Inhibitors from Actinomycetes; Identification of Trichostatin Derivatives from Streptomyces sp. CA-129531 and Scale Up Production in Bioreactor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 126952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.-H.; Ha, S.-M.; Kwon, S.; Lim, J.; Kim, Y.; Seo, H.; Chun, J. Introducing EzBioCloud: A Taxonomically United Database of 16S rRNA Gene Sequences and Whole-Genome Assemblies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 1613–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EzBioCloud. Available online: https://www.ezbiocloud.net/ (accessed on 1 June 2019).

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, J.D.; Gibson, T.J.; Plewniak, F.; Jeanmougin, F.; Higgins, D.G. The CLUSTAL_X Windows Interface: Flexible Strategies for Multiple Sequence Alignment Aided by Quality Analysis Tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 4876–4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The Neighbor-Joining Method: A New Method for Reconstructing Phylogenetic Trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar]

- Jukes, T.H.; Cantor, C.R. Evolution of Protein Molecules. In Mammalian Protein Metabolism (Vol. III); Munro, H.N., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1969; pp. 21–132. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, J.D.; Vitorino, I.; De la Cruz, M.; Díaz, C.; Cautain, B.; Annang, F.; Pérez-Moreno, G.; Gonzalez Martinez, I.; Tormo, J.R.; Martín, J.M.; et al. Bioactivities and Extract Dereplication of Actinomycetales Isolated from Marine Sponges. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfey, P. Determination of D-Amino Acids. II. Use of a Bifunctional Reagent, 1,5-Difluoro-2,4-Dinitrobenzene. Carlsberg Res. Commun. 1984, 49, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaita, E.; Lambrinidis, G.; Cheimonidi, C.; Agalou, A.; Beis, D.; Trougakos, I.; Mikros, E.; Skaltsounis, A.-L.; Aligiannis, N. Anti-Melanogenic Properties of Greek Plants. A Novel Depigmenting Agent from Morus alba Wood. Molecules 2017, 22, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grathwohl, C.; Wüthrich, K. NMR Studies of the Rates of Proline Cis–Trans Isomerization in Oligopeptides. Biopolymers 1981, 20, 2623–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreotti, A.H. Native State Proline Isomerization: An Intrinsic Molecular Switch. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 9515–9524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, D.; Danielson, J.A.; Tasnim, A.; Zhang, J.T.; Zou, Y.; Liu, J.Y. Proline Isomerization: From the Chemistry and Biology to Therapeutic Opportunities. Biology 2023, 12, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidelman, Z. Casein Derived Peptides and Therapeutic Uses Thereof. U.S. Patent US20070203060A1, 30 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Picariello, G.; Ferranti, P.; Fierro, O.; Mamone, G.; Caira, S.; Di Luccia, A.; Monica, S.; Addeo, F. Peptides Surviving the Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion of Milk Proteins: Biological and Toxicological Implications. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2010, 878, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Ren, J.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, H.; Regenstein, J.M.; Li, Y.; Wu, J. Isolation and Characterization of Three Novel Peptides from Casein Hydrolysates that Stimulate the Growth of Mixed Cultures of Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 7045–7053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, F.; Cai, M.-H.; Chen, B.; Xiao, W.; Li, X.-W.; Guo, Y.-W. Absolute Configuration of (2R,3R,6S,8R)-Methyl Homononactate, a Polyketide from Actinomycetes Streptomyces sp. R-527F of the Arctic Region. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2018, 54, 821–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayatilake, G.S.; Thornton, M.P.; Leonard, A.C.; Grimwade, J.E.; Baker, B.J. Metabolites from an Antarctic Sponge-Associated Bacterium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Nat. Prod. 1996, 59, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Khan, A.L.; Ali, L.; Rizvi, T.S.; Khan, S.A.; Hussain, J.; Hamayun, M.; Al-Harrasi, A. Enzyme Inhibitory Metabolites from Endophytic Penicillium citrinum Isolated from Boswellia sacra. Arch. Microbiol. 2017, 199, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyrat, L.A.; Tsafantakis, N.; Georgousaki, K.; Ouazzani, J.; Genilloud, O.; Trougakos, I.P.; Fokialakis, N. Terrestrial Microorganisms: Cell Factories of Bioactive Molecules with Skin Protecting Applications. Molecules 2019, 24, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.; Ku, S.-K.; Choi, H.; Bae, J.-S. Three Diketopiperazines from Marine-Derived Bacteria Inhibit LPS-Induced Endothelial Inflammatory Responses. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 1873–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buedenbender, L.; Robertson, L.P.; Lucantoni, L.; Avery, V.M.; Kurtböke, D.İ.; Carroll, A.R. HSQC-TOCSY Fingerprinting-Directed Discovery of Antiplasmodial Polyketides from the Marine Ascidian-Derived Streptomyces sp. (USC-16018). Marine Drugs 2018, 16, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solecka, J.; Rajnisz-Mateusiak, A.; Guspiel, A.; Jakubiec-Krzesniak, K.; Ziemska, J.; Kawęcki, R.; Kaczorek, D.; Gudanis, D.; Jarosz, J.; Wietrzyk, J. Cyclo(Pro-DOPA), a Third Identified Bioactive Metabolite Produced by Streptomyces sp. 8812. J. Antibiot. 2018, 71, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Hwang, I.H.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, M.-A.; Hwang, J.S.; Kim, Y.H.; Na, M. Quinoxaline-, Dopamine-, and Amino Acid-Derived Metabolites from the Edible Insect Protaetia brevitarsis seulensis. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2017, 40, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).