Abstract

The aerial parts of Smilax canariensis Brouss. ex Willd., an endemic plant species of the Canary Islands and Madeira, were chemically investigated, resulting in the isolation of multiple known and novel compounds. These include known flavonol glycosides: quercetin-3-O-rutinoside, rutin (7), quercetin-3-O-rutinoside decaacetate (7a), kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside nonaacetate, nicotiflorin acetate (8), 2-O-p-coumaroylglycerol triacetate (10), and trans-resveratrol (9). Additionally, a new sterol, 24,24-dimethy-5α-cholesta-7,25-dien-3-one (1), and two novel dammarane-type triterpenes, 24-hydroxy-24-methyl-dammara-20,25-dien-3-one (2) and 3-acetyl-25-methyl-dammara-20,24-diene (3), were identified. In addition, stigmasterol, sitosterol, and stigmast-4-en-3-one (4) were obtained. The structural elucidation of these compounds was achieved via 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, and comparison with literature data. This study provides the first phytochemical profile of S. canariensis and highlights its potential as a source of bioactive compounds for pharmacological applications.

1. Introduction

The genus Smilax (Liliaceae) comprises over 350 species distributed widely across tropical and temperate regions, with notable applications in traditional medicine, particularly in East Asia and North America [1,2]. Many of them have long been used as medicinal herbs, especially as traditional Chinese medicines in China [3,4], for their diuretic, laxative, depurative, and hypoglycemic properties, whereas only four species are found in Europe: Smilax aspera, located in the Mediterranean basin; Smilax azorica, native to the Azores Islands; Smilax excelsa, in the Black Sea and Caspian Sea region, and Smilax canariensis Brouss. ex Willd., endemic to Madeira and the Canary Islands, which is the subject of our study.

Morphologically, S. canariensis is characterized by leaves with three to five nerves and a simple umbel inflorescence. It is an evergreen, lauriform plant that is narrower at the ends of the older branches, and there are few or no thorns on the older stems. Notably, when the fruit ripens, it acquires a dark color.

Traditional medicine in the Canary Islands has extensively utilized endemic plants, including S. canariensis, commonly known as “zarzaparrilla sin espinas” [5]. This plant is well regarded for its diuretic, laxative, depurative, and hypoglycemic properties [6]. Despite these traditional uses, the phytochemical composition of S. canariensis has not been extensively studied, presenting a significant opportunity to explore its chemical constituents and potential bioactivities [3,7]. This study aims to address this gap by isolating and characterizing the secondary metabolites present in the aerial parts of this species, thereby uncovering potential pharmacologically active compounds [8] and contributing to the understanding of their chemical diversity. As far as we are aware, this plant has not previously been the subject of phytochemical analysis.

2. Experimental

2.1. General

Melting points were measured on a Reichert Thermovar apparatus without correction. Optical rotations were recorded on a Perkin Elmer 2H polarimeter equipped with a 1 dm cell. NMR spectra (1H and 13C) were obtained via Bruker Advance II 500 and Bruker Advance III 600 spectrometers (Bruker Corp., Bremen, Germany) in CDCl3, C6D6, CD3COCD3, and C5D5N, with residual solvent signals serving as internal references, (δH 7.26; δC 76.7), (δH 7.16; δC 128.39), (δH 2.05, δC 29.92), and (δH 8.74, 7.58, 7.22; δC 150.35, 135.91, 123.87), respectively. The pulse conditions for 1D and 2D NMR were as follows [9]. Mass spectrometry (ESI-TOF and EI-MS) was performed using a Micromass LCT Premier XE and a Micromass Autospec instrument (Waters, Manchester, UK) at 70 eV, respectively. Column chromatography was performed on Amberlite XAD 2 (Supelco XAD-2-3019, Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany), Sephadex LH-20 Pharmacia (ref. 17-0090-01), silica gel (230-400 mesh, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), octadecyl-functionalized silica gel (377635-1006, Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany), and analytical TLC (Kieselget 60 F254, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). HPLC separations were carried out on a JASCO Pu-980 series pumping system equipped with a JASCO UV-975 detector (JASCO Corp., Tokyo, Japan) and a Waters Kromasil Si 5 mm (10 × 250 mm) column (Waters, Manchester, UK). A Macherey–Nagel VP 250/10 nucleodur Sphinx RP 5 µm column (Macherey-Nagel, Duren, Germany) was used for HPLC‒RP chromatography. Chromatograms were visualized under UV light at 255 and 366 nm and/or sprayed with oleum followed by heating. All the solvents were distilled before use. For acetylation, dry phenolic material was dissolved in the minimum volume of pyridine. Two times the amount of acetic anhydride was added, and the mixture was left to stand overnight at ambient temperature. The mixture was then diluted with H2O and extracted three times with ethyl acetate. The organic phase was evaporated at reduced pressure, and the residue was further purified by HPLC (SiO2 column) using EtOAc-hexane as the eluent. NMR spectra are given in the Supplementary Materials (Figures S1–S19).

2.2. Plant Material

The aerial parts of Smilax canariensis Brouss. ex Willd. were collected in April 2011 from Las Nieves (Velhoco) and Santa Cruz de La Palma (UTM coordinates: 228115/3177048). The plant was identified by Prof. Pedro Luis Pérez de Paz from the Department of Botany, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of La Laguna, where a voucher specimen (TFC: 49.941) has been deposited.

2.3. Extraction and Isolation of the Constituents

The fresh aerial parts of Smilax canariensis (7.5 kg) were finely divided and subjected to exhaustive extraction with ethanol at ambient temperature for two weeks. The resulting extract was filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure, yielding 240 g of brown residue. This residue was dissolved in two liters of distilled water and extracted with dichloromethane to yield 30.4 g of residue, followed by n-butanol extraction, which yielded 11 g of residue. The remaining aqueous layer was concentrated to yield 125 g of residue.

The dichloromethane extract (30.4 g) of S. canariensis was adsorbed onto silica gel and subjected to column chromatography on silica gel (230–400 mesh, 300 g, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The column was eluted with stepwise gradients of n-hexane and ethyl acetate, yielding 109 fractions (600 mL each). The evolution of this chromatography system was followed by the addition of CCF. Fractions SH1–15 (1.5 g) were eluted with pure n-hexane, which consists of a complex mixture of essential oils, and were not investigated further. Fractions SH16–17 were purified by precipitation in MeOH, resulting in a white solid, which was identified as 24,24-dimethy-5α-cholesta-7,25-dien-3-one (1; 85 mg). Fractions SH39–41 (152 mg) were purified via column chromatography over Sephadex LH-20 (hex:CH2Cl2:MeOH, 2:1:1) and an SHT column. Subfraction SHT5–6 was re-chromatographed over a SiO2 column and used as an eluent mixture of benzene–EtOAc, totaling 18 fractions of 10 mL each. Subfractions 8–9 yielded 17 mg of Stigmast-4-en-3-one (4), which showed significant hypoglycemic activity [10].

Subfraction SHT8–9 (28 mg) was further purified on Sephadex LH-20 (hex:CH2Cl2:MeOH, 2:1:1) to yield 12 mg of 25-methyldammara-20, 24-diene-3-β-yl-acetate. Fractions SH51–55 were eluted with a 7:3 hexane–EtOAc mixture, yielding 218 mg of colorless crystals with a melting point of 125 °C in acetone (lit. mp 130 °C) [11], identified as a 3:1 mixture (for the integral) of β-sitosterol (5) and stigmasterol (6), respectively.

Fractions SH58–67 (235 mg) were chromatographed on Sephadex LH-20 (hex:CH2Cl2:MeOH, 2:1:1) columns, and fractions of 15 mL each were collected. A total of 35 fractions were collected, which, according to their behavior in the CCF, were regrouped into SHS11–12 (25 mg) and SHS20–22 (14 mg). Subsequent purification of SHS20–22 by HPLC (hexane:ethyl acetate, 9:1) allowed us to obtain the majority of the products (Tr = 40 min, flow rate of 2 mL min−1), identified as ethyl p-hydroxybenzoate (11; 8 mg). Subfractions SHS11–12 were obtained after chromatography via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; SiO2, EtOAc–Hex 8:2, flow ratio of 2 mL min−1, Tr 22 min), with 12 mg of 24-hydroxy-24-methyl-dammara-20, 25-dien-3-one (2).

Fractions SH89–97 (337 mg) were chromatographed on Sephadex LH-20 (hex:CH2Cl2:MeOH, 2:1:1, SHY column), and subfractions SHY20–23 yielded 34 mg of a substance with strong UV absorption (Rf = 0.32, hexane:ethyl acetate 20%) at the melting point (114–116 °C, MeOH). This compound was identified from its physical and spectroscopic data as p-hydroxybenzaldehyde (12) [6].

A 5.5 g portion of the n-butanol extract was subjected to low-pressure chromatography on an RP C-18 column (7 × 40 cm) with a linear gradient of 40, with 500 mL H2O–MeOH mixtures beginning with H2O and ending with MeOH and an SM column. Fractions SM20–24 (740 mg) were re-chromatographed on Sephadex LH-20 (CH2Cl2:MeOH, 1:1, SpH column). Fractions SpH8–9, after precipitation in methanol/dichloromethane, yielded 16.5 mg of trans-resveratrol (9) [12]. Fraction SpH (22.5 mg) was purified by precipitation in a methanol‒ethyl acetate mixture to yield rutin (7; 7.1 mg), and the mother liquor, which was composed of a complex mixture of flavonoids, was acetylated with acetic anhydride in pyridine for 12 h. After elimination of the solvent in vacuo, 12.5 mg of the crude product, which was re-chromatographed via HPLC (SiO2, EtOAc‒Hex 7:3, flow 2 mL min−1), was obtained. Three pure products were obtained: quercetin-3-O-rutinose decaacetate (rutin acetate (7a), 3.7 mg, Tr: 20.2 min), kaempferol-3-O-rutinose nonaacetate (nicotiflorin acetate (8), 3.4 mg, Tr: 17.6 min), and 2-O-p-coumaroylglycerol triacetate (10; 2.8 mg, Tr: 9.76 min).

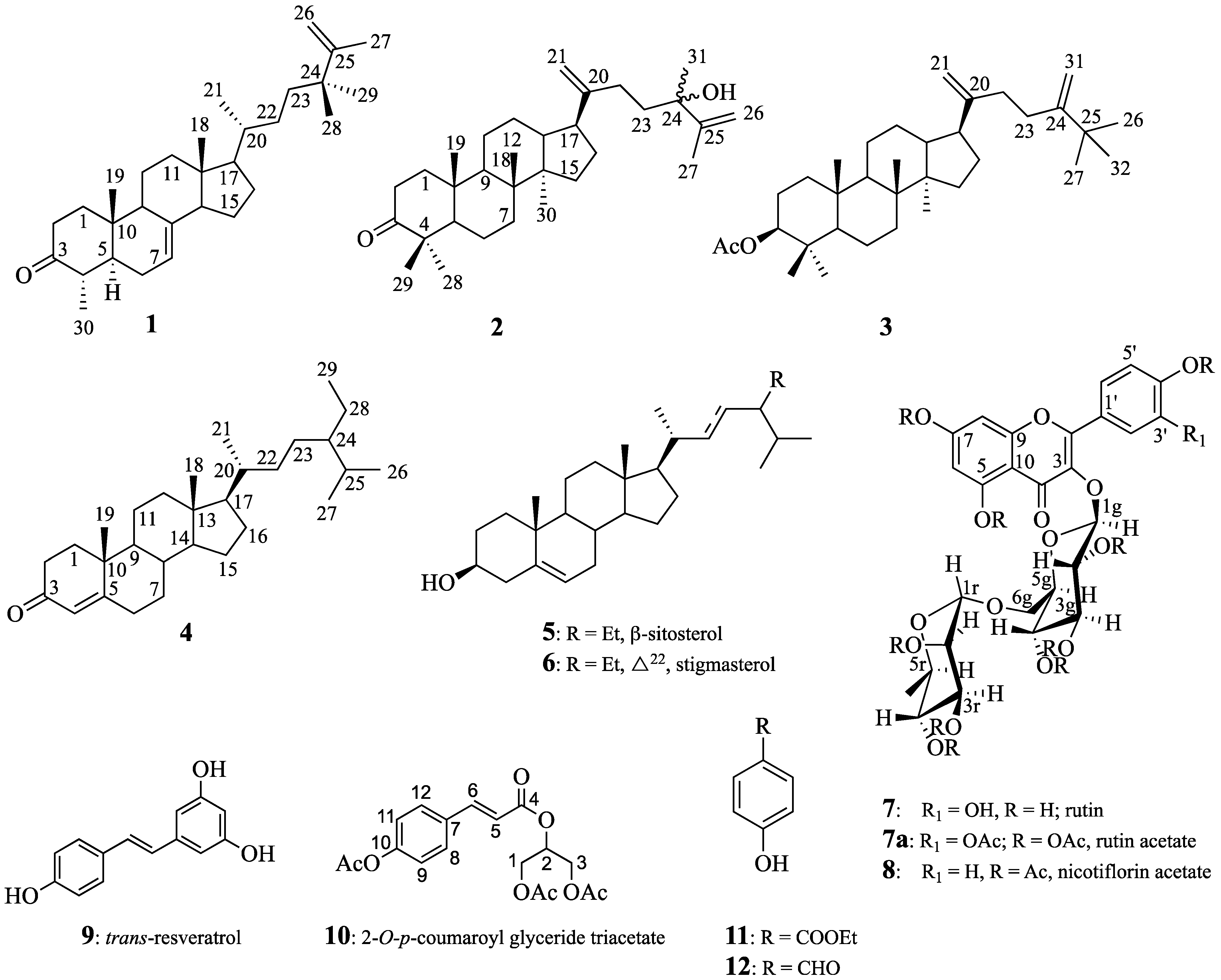

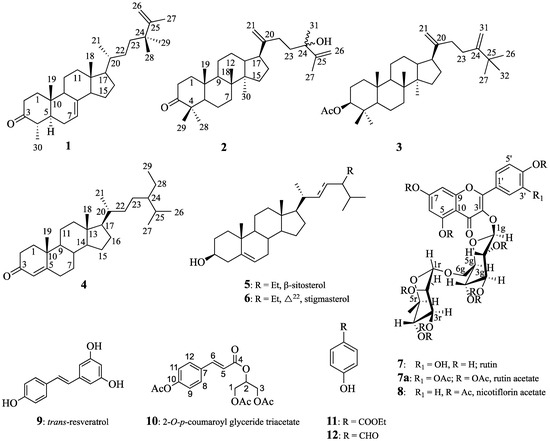

Chemical structures of all identified products are provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structures of compounds 1–12.

2.3.1. 24,24-Dimethyl-5α-cholesta-7,25-dien-3-one (1)

Colorless needles, mp 138–140 °C, MeOH. 1H 13C NMR (see Table 1), HREI-MS, m/z 447.3610 (calcd. for C30H48O, 447.3603) [M+Na]+ (100%).

2.3.2. 24-Hydroxy-24-methyl-dammara-20,25-dien-3-one (2)

Viscous oil, 1H 13C NMR (see Table 2), HRESIMS, m/z 477.3706 (calcd. for C31H50O2, 477.3709) [M+Na]+.

2.3.3. 25-Methyldammara-20,24-diene-3-β-yl-acetate (3)

Amorphous white solid, mp 120–122 °C, hexanes. 1H 13C NMR (see Table 2), HRESIMS, m/z 519.4174 (calcd. for C34H56O2, 519.4178) [M+Na]+.

2.3.4. Stigmast-4-en-3-one (4)

Amorphous solid, mp 77–80 °C (lit. mp 87–88 °C) [10], and for the 1H 13C NMR data, see Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials. HREIMS mass spectrometry showed the molecular ion peak at m/z 435.3592 (calcd. for C29H48O, 435.3603) [M+Na]+.

2.3.5. Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside, Rutin (7)

Compound 7 was isolated as a yellow solid with a melting point of 240 °C and presented a molecular formula of C27H30O16, which was determined by high-resolution electron ionization mass spectrometry (HREIMS) and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), with a molecular ion peak at m/z 609.1460 (calcd. for C27H29O16, 609.1456) [M−H]+. Peracetylation of 7 afforded the known rutin decaacetate 7a, and both were identified by MS and 1H and 13C NMR spectrometry [13,14].

2.3.6. Kaempherol-3-O-rutinosidenonaacetate, Nicotiflorin Acetate (8)

The molecular formula of C45H48O24 was determined by HREIMS, which revealed a molecular ion peak at m/z 995.2460 (calcd. for C45H48O24+Na, 995.2433) [M+Na]+. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were obtained [15].

2.3.7. trans-Resveratrol (3,4′,5-Trihydroxystilbene) (9).

Compound 9 was isolated as a yellow solid with a melting point of 254 °C (lit. mp 265–268 °C) [12]. The molecular formula C14H12O3 was determined by HREIMS, which revealed a molecular ion peak at m/z 227.0711 (100%; calcd. for C14H11O3, 227.0708) [M-H]+. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were obtained [12].

2.3.8. 2-O-p-Coumaroylglycerol Triacetate (Juncusyl Ester B Triacetate) (10)

The molecular formula C18H20O8 was determined by HREIMS, which revealed a molecular ion peak at m/z 387.1061 (100%; calcd. for C18H20O8+Na, 387.1056) [M+Na]+. 1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ: 4.33 (1H, dd, J = 12.06, 4.02 Hz, H1a), 4.25 (1H, dd, J = 12.06, 4.16 Hz, H1b), 5.38 (1H, dddd, J = 6.03, 5.89, 4.16 and 4.02 Hz, H2), 4.20 (1H, dd, J = 11.92, 6.03 Hz, H3a), 4.05 (1H, dd, J = 11.92, 5.89 Hz, H3b), 6.39 (2H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, H8,12), 6.11 (2H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, H9,11), 1.70, 1.68, 1.62 (each 3H, s, Ac). 13C NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ: 62.97 C-1, 69.97 C-2, 62.82 C-3, 166.4 C-4, 118.11 C-5, 144.96 C-6, 132.29 C-7, 129.82 C-8, 12, 122.64 C-9, 11, 152.9 C-10 (20.81, 168.41; 20.81, 170.15; 20.49, 169.99), 3Ac. The signal assignments of H-1 and C-1 can be interchanged with those of H-3 and C-3.

2.3.9. Ethyl p-Hydroxybenzoate (11)

The molecular formula C9H9O3 was determined by HREIMS, which revealed a molecular ion peak at m/z 165.0548 (100%; calcd. for C9H9O3, 165.0552) [M]+. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were obtained [16].

2.3.10. p-Hydroxybenzaldehyde (12)

Compound 12 was isolated as an amorphous solid with a melting point of 114–116 °C in MeOH (lit. mp 115–116 °C (from ethanol)) [17]. The molecular formula C7H5O2 was determined by HREIMS, which revealed a molecular ion peak at m/z 121.0293 (100%; calcd. for C7H5O2, 121.0290) [M-H]+. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were obtained [17].

3. Results and Discussion

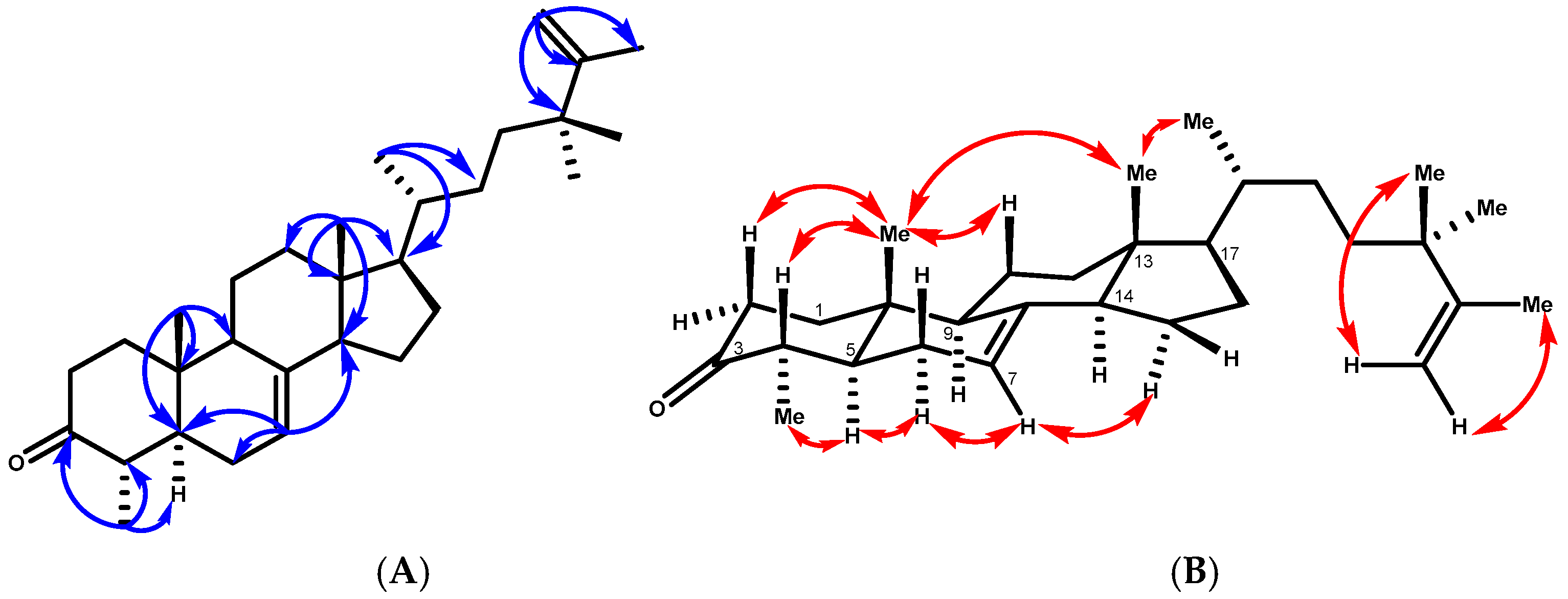

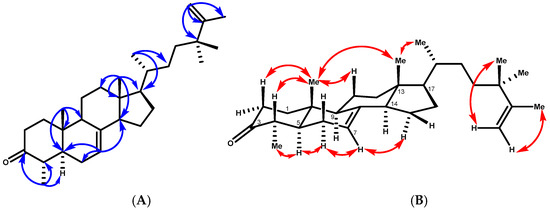

Compound 1 was obtained as colorless needles, mp 138–140 °C. Its molecular formula was determined to be C30H48O by HREIMS at m/z 447.3609 (calcd. for [C30H48O+Na]+, 447.3603), together with its 13C NMR data, indicating seven degrees of unsaturation. Three of the implied seven degrees of unsaturation were explained by multiple bonds, two by carbon–carbon double bonds and one by a carbon–oxygen double bond; consequently, 1 was a tetracyclic triterpene. The 1H NMR spectrum in benzene of 1 indicated two tertiary methyl protons at δH 0.59 and 0.80 ppm, one secondary methyl proton at δH 1.06 (d, J = 6.5 Hz), and an olefinic proton at δH 5.16 (br dd, J = 5.6 and 2.0 Hz), which are characteristic signals of 18-H3, 19-H3, 30-H3, and H-7 of 1 having a lophenol ring system [18]. The carbon signals (Table 1) due to the ring systems of 1 were almost identical to those of 4 obtained after ketonization of 24(R)-ethyllophenol [19]. The presence of the ketone at C-3 was evident in the 13C NMR spectrum since it showed a carbonyl signal at δC 210.5, which presented cross-peaks between the protons at C-1, C-2, and C-4 and the methyl group at C-4 in the HMBC spectrum. The structure of 1 was further elucidated by analysis of its HMBC spectrum (Figure 2). The C-18 and C-19 methyl groups were positioned at the ring junctions C-13 and C-10 on the basis of the HMBC correlations of 18-H3/C-12, C-13, C-14, and C-17 and 19-H3/C-1, C-5, C-9, and C-10, respectively.

Figure 2.

(A) Key HMBC correlations of compound 1. (B) T-ROESY correlations (C6D6) of compound 1.

Table 1.

1H and 13C NMR data of 24,24-dimethyl-5α-cholesta-7,25-dien-3-one (1).

Table 1.

1H and 13C NMR data of 24,24-dimethyl-5α-cholesta-7,25-dien-3-one (1).

| Position | 1H a | 1H b | 13C a | 13C b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 2.05 m | 1.99 dt (12.4, 3.12) | 39.8 | 40.18 |

| 1b | 1.25 m | 1.73 m | ||

| 2a | 2.48 td (14.3, 5.7) | 2.21 ddd (13.6, 3.9, 2.6) | 38.3 | 38.3 |

| 2b | 2.30 m | 2.09 td (13.6, 5.6) | ||

| 3 | 213.4 | 210.5 | ||

| 4 | 2.13 m | 1.88 m | 45.8 | 45.9 |

| 5 | 1.20 m | 1.73 m | 50.5 | 50.5 |

| 6a | 2.15 m | 1.92 m | 28.1 | 28.5 |

| 6b | 1.90 m | 1.54 m | ||

| 7 | 5.21 brs | 5.16 br dd (5.6, 2.0) | 117.4 | 118.4 |

| 8 | 139.4 | 139.3 | ||

| 9 | 1.75 m | 1.48 m | 49.5 | 49.8 |

| 10 | 35.4 | 35.5 | ||

| 11a | 1.61 m | 1.49 m | 22.1 | 22.1 |

| 11b | 1.55 m | 1.38 m | ||

| 12a | 2.16 m | 1.73 m | 40.1 | 39.8 |

| 12b | 1.48 m | 1.13 m | ||

| 13 | 43.6 | 43.9 | ||

| 14 | 1.80 m | 1.73 m | 55.1 | 55.5 |

| 15a | 1.53 m | 1.55 m | 23.7 | 23.7 |

| 15b | 1.42 m | 1.43 m | ||

| 16a | 1.79 m | 1.90 m | 29.8 | 28.6 |

| 16b | 1.27 m | 1.28 m | ||

| 17 | 1.25 m | 1.20 m | 56.1 | 56.6 |

| 18 | 0.56 m | 0.59 s | 12.07 | 12.4 |

| 19 | 1.08 s | 0.80 s | 13.9 | 13.8 |

| 20 | 1.33 m | 1.33 m | 36.8 | 37.5 |

| 21 | 0.92 d (6.4) | 0.99 d (6.5) | 19.2 | 19.6 |

| 22a | 1.24 m | 1.33 m | 30.6 | 31.3 |

| 22b | 0.88 m | 0.98 m | ||

| 23a | 1.40 m | 1.45 m | 37.5 | 38.0 |

| 23b | 1.20 m | 1.23 m | ||

| 24 | 28.9 | 39.3 | ||

| 25 | 152.5 | 152.4 | ||

| 26a | 4.73 brs | 4.88 brs | 109.5 | 110.6 |

| 26b | 4.66 brs | 4.85brs | ||

| 27 | 1.69 brs | 1.71 brs | 19.6 | 20.0 |

| 28 | 1.01 c | 1.06 d (6.5) | 11.6 | 12.5 |

| 29 | 1.01 s | 1.08 s | 27.7 | 27.8 |

| 30 | 1.02 s | 1.08 s | 27.4 | 28.1 |

a CDCl3, 600, 150 MHz. b C6D6, 600, 150 MHz. c Partially hidden.

The HMBC correlations placed the side chain at C-17 of the lophenol skeleton (Figure 2). This was evidenced by the methine proton (δH 1.20, m, H-17) correlating with carbons at δC 28.6 (C-16), 31.3 (C-22), 43.9 (C-13), and 55.5 (C-14), along with δC 19.6 (C-21). Furthermore, the methyl protons 21-H3 (δH 0.99, d, J = 6.5 Hz) were strongly correlated with δC 56.6 (C-17), 37.5 (C-20), and 31.3 (C-22), confirming the structure of the side chain. In addition, the 1H-NMR spectrum of 1 showed a vinyl methyl signal at δH 1.71 (3H, brs) and a terminal methylene proton at δH 4.85 and 4.88 (1H, each, brs, H-26a, b) due to an isopropenyl group and two tertiary methyl protons at δH 1.08 (6H, s, 28-H3, 29-H3). The cross-peaks observed between the vinylic protons H-26 a, b and the carbon signals at δC 152.4 (C-25) and 20.0 (C-27), and with the methyl protons at δH 1.08 (6H, s, 28-H3, 29-H3) and C-25, C-26, and C-23, were consistent with the placement of the extra two methyl groups at C-24. The relative configurations of compound 1 were determined by the T-ROESY spectrum. The T-ROESY correlations (Figure 2B) from 19-H3 to 18-H3 and H-4 indicated that they were co-facial, assigned as β-orientation. Consequently, the T-ROESY correlations from H-5 to 28-H3 and H-6a revealed that they were α-oriented. The NMR spectroscopic features of compound 1 were analogous to those of 4α,24,24-trimethyl-5α-cholesta-7,25-dien-3β-ol (24,24-dimethyl-25-dehydrolophenol; 1a), which was isolated as the acetyl derivative from the unsaponifiable lipid of Clerodendrum inerme [20], except that 1 had a keto carbon at δC 210.5, where 1a had 3β-acetate; hence, 1 was considered to have the structure 24,24-dimethy-5α-cholesta-7,25-dien-3-one.

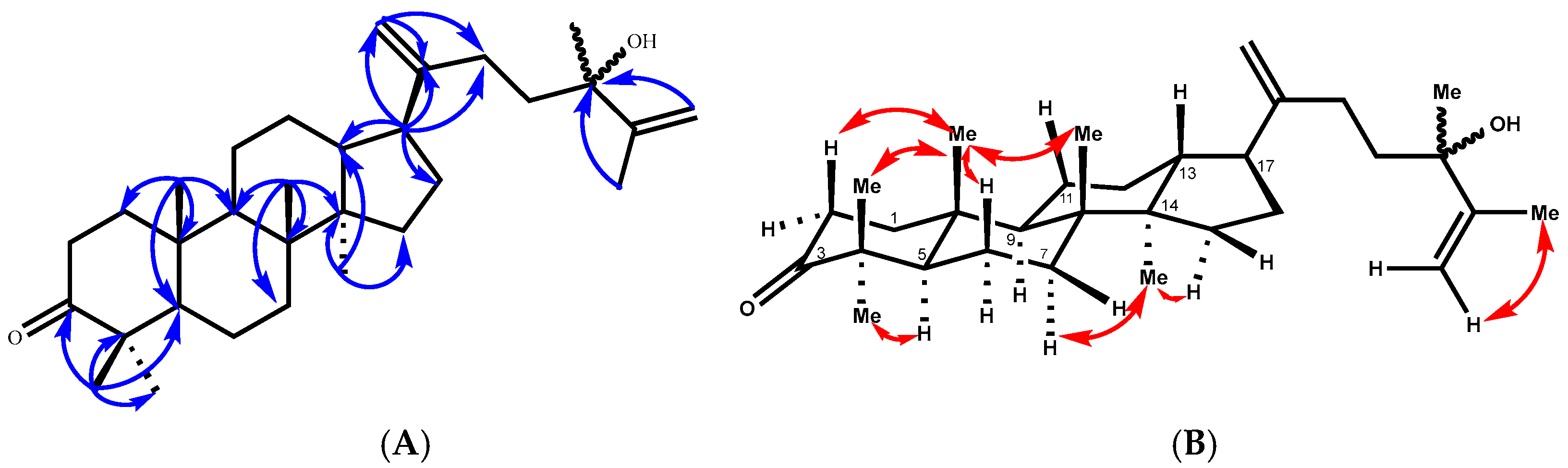

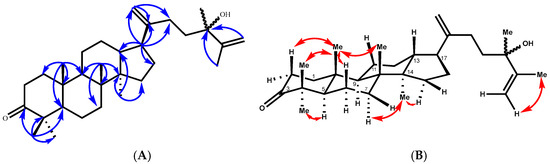

Compound 2 was isolated as a viscous oil, and its molecular formula is C31H50O2, as deduced from its positive HREIMS (found [M+Na]+ m/z 477.3706, calcd. 477.3709) and 13C NMR data, which are indicative of seven indices of hydrogen deficiency. The 13C NMR (Table 2) data revealed 31 carbon resonances, which were classified by the HSQC spectrum as 7 methyl, 12 methylene (2 of them as terminal double bonds), 4 methine, and 8 quaternary carbons, including 2 olefinic carbons at δC 153.8 (C-20) and 150.9 (C-25) and 1 carbonyl at δC 215.5 (C-3). Three of the implied six degrees of unsaturation were explained by multiple bonds, two by carbon‒carbon double bonds and one by a carbon‒oxygen double bond; consequently, 2 was a tetracyclic triterpene. Detailed analysis of the 13C NMR data confirmed that compound 2 belongs to the dammarane-type triterpene class, characterized by the presence of an additional methyl group. The 1H NMR spectrum exhibited seven distinct tertiary methyl signals at δH 0.70, 0.80, 1.64, 1.16, 0.99, 1.09, and 0.87 ppm (each integrating for three protons, singlets), which is consistent with this classification. These data corresponded to a dammarane triterpene skeleton similar to that of 24-methyldammara-20,25-dien-3-one isolated from Copernicia prunifera [21] and from Cissus quadrangularis [22]. The structure of 2 was deduced from its HMBC spectrum (Figure 3). The HMBC correlations between the tertiary methyl protons and their neighboring carbons were employed to establish the dammarane backbone.

Figure 3.

(A) Key HMBC correlations of compound 2. (B) T-ROESY correlations (C6D6) of compound 2.

Table 2.

1H (600 MHz) and 13C (150 MHz) NMR data of 24-hydroxy-24-methyl-dammara-20,25-dien-3-one (2) and 3-acetyl-25-methyl-dammara-20,24-diene (3) in C6D6.

Table 2.

1H (600 MHz) and 13C (150 MHz) NMR data of 24-hydroxy-24-methyl-dammara-20,25-dien-3-one (2) and 3-acetyl-25-methyl-dammara-20,24-diene (3) in C6D6.

| δH (J Values are Given in Hz) | δC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atom/Position | (2) | (3) | (2) | (3) |

| H-1a | 1.87 m | 1.41 m | 40.1 | 39.1 |

| H-1b | 0.95 m | 0.71 m | ||

| H-2a | 2.27 m | 1.71 m | 34.4 | 24.5 |

| H-2b | 2.23 m | 1.58 m | ||

| H-3 | C-3 | 4.69 d d (11.8, 4.5) | 215.5 | 80.8 |

| C-4 | 47.6 | 38.4 | ||

| H-5 | 1.10 m | 0.69 d d (11.9, 2.7) | 55.6 | 56.5 |

| H-6a | 1.31 m | 1.41 m | 20.1 | 18.8 |

| H-6b | 1.22 m | 1.32 m | ||

| H-7a | 1.40 m | 1.49 t d (12.9, 4.1) | 35.3 | 35.9 |

| H-7b | 1.14 m | 1.20 m | ||

| C-8 | 40.7 | 41.1 | ||

| H-9 | 1.15 m | 1.18 m | 50.7 | 51.4 |

| C-10 | 37.2 | 37.7 | ||

| H-11a | 1.17 m | 1.74 m | 22.35, 22.33 | 25.8 |

| H-11b | 1.05 m | 1.11 m | ||

| H-12a | 1.56 (2H, m) | 1.36 m | 25.6 | 22.0 |

| H-12b | 1.56 (2H, m) | 1.11 m | ||

| H-13 | 1.79 m | 1.80 d d (11.7, 3.5) | 46.26, 46.07 | 46.2 |

| C-14 | 49.9 | 49.4 | ||

| H15a | 1.60 m | 1.62 m | 31.96, 31.94 31.96, 31.94 | 32.1 |

| H-15b | 1.08 m | 1.11 m | ||

| H-16a | 1.99 m | 1.34 m | 29.9, 29.8 | 30.5 |

| H16b | 1.57 m | 1.34 m | ||

| H-17 | 2.31 m | 2.37 m | 48.58, 48.47 | 48.7 |

| Me 18 | 0.80 brs | 0.92 s | 16.3 | 15.5 |

| Me-19 | 0.70 s | 0.75 s | 16.4 | 16.8 |

| C-20 | 153.86, 153.81 | 153.4 | ||

| H-21a | 4.97 brs | 5.00 brs | 108.12, 108.05 | 108.5 |

| H-21b | 4.93 m | 4.91 brs | ||

| H-22a | 2.23 m | 2.32 m | 29.56, 29.55 | 35.17 |

| H-22b | 2.07 m | 2.32 m | ||

| H-23a | 1.77 (2H, m) | 2.33 m | 39.7, 40.0 | 31.26 |

| H-23b | 1.77 (2H, m) | 2.33 m | ||

| C-24 | 75.38, 75.32 | 158.19 | ||

| C-25 | 150.9 | 36.7 | ||

| H-26a | 5.04 brs | 1.09 s (Me-26) | 110.4 | 29.5 |

| H-26b | 4.91 brs | |||

| Me-27 | 1.64 brs | 1.09 s | 19.95 | 29.5 |

| Me-28 | 1.09 s | 0.89 s | 27.15 | 28.5 |

| Me-29 | 0.99 s | 0.90 s | 21.5 | 17.2 |

| Me-30 | 0.87 s | 0.86 s | 15.7 | 16.5 |

| H-31a | 1.16 s (Me-31) | 5.04 br s H31a | 28.71, 28.68 | 106.14 |

| H-31a | 4.91 brs H31b | |||

| Me-32 | 1.08 s | 29.5 | ||

| Ac | 1.75 (3H, s) | 21.3, 170.3 | ||

Values in italic correspond to the minor isomer.

All expected correlations (Me-18 → C-8, 7, 9, 14; Me-19 → C-10, 1, 5, 9; Me-30 → C-14, 8, 13, 15) displayed strong cross-peaks. Additionally, the HMBC spectrum placed the keto carbon at C-3 (Figure 3), from which the methyl proton at δH 0.99 (Me-29) correlated with the carbon at δC 28.7 (C-28), 47.6 (C-4), 55.5 (C-5), and 215.3 (C-3). The side chain was placed at C-17 of the main skeleton from the HMBC correlation of the methine proton at δH 2.31 (m, H-17), with the carbons at δC 29.9 (C-16), 29.5 (C-22), 46.2 (C-13), 40.9 (C-14), 108.1 (C-21), and 153.8 (C-20), and the terminal olefinic methylene protons at δH 4.97 brs and 4.93 brs (2H, H-21a, b), with the carbons at δC 29.5 (C-22), 48.5 (C-17), and 153.8 (C-20). The HMBC experiments also confirmed the presence of a methyl group at δH 1.16 s, HSQC 28.7/28.68, and a methyl group on an oxygen-bearing carbon atom at C-24 (δC 75.38/75.32), since long-range couplings were observed between C-24 and the protons of the vinyl methyl group (H-27 at δH 1.651/1.639 brs), the terminal methylene (H-26a, δH 5.12 brd, 1.3 Hz), and H-26b at δH 4.86 dd (2.7 and 1.3 Hz). The relative configurations of compound 2 were determined by the T-ROESY spectrum. The T-ROESY correlations (Figure 3B) from 19-H3 to 18-H3, 29-H3, H-2a, and H-6a indicated that they were co-facial, assigned as β-orientation. Consequently, the T-ROESY correlations from H-5 to 28-H3 and H-6b revealed that they were α-oriented.

The 13C NMR spectrum of compound 2 showed splitting of the signals of certain carbons (Table 2). The splitting of these carbon signals is in agreement with the presence of a mixture of C-24 epimers [23]. On the basis of this combined evidence, the structure of 2 is defined as a 24-epimer mixture of 24-hydroxy-24-methyldammara-20,25-dien-3-one.

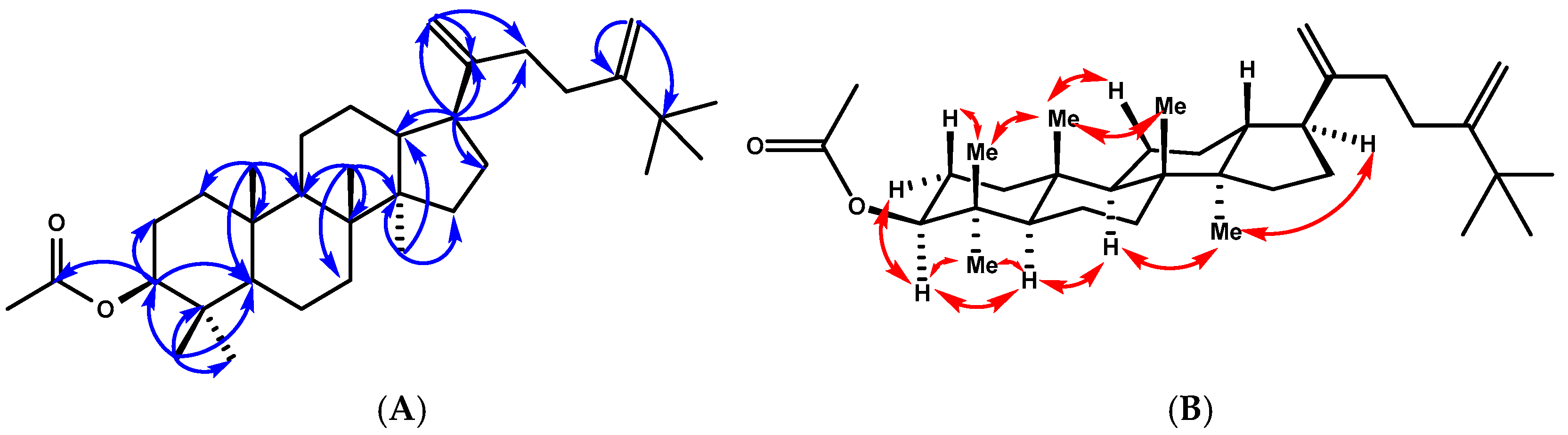

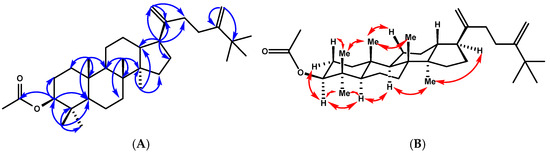

Compound 3 was obtained as a white amorphous solid, mp (120–122 °C, hexanes). Its molecular formula was determined to be C34H56O2 on the basis of its HREIMS peak at m/z 519.4174 [M+Na]+ (calcd. for C34H56O2, 519.4178), which is indicative of seven indices of hydrogen deficiency. Three of the implied seven degrees of unsaturation were explained by multiple bonds, two by carbon–carbon double bonds and one by a carbon–oxygen double bond; consequently, 3 was a tetracyclic triterpene. Its 1H and 13C NMR in benzene (Table 2) were very similar to those of 2. The structural difference between 3 and 2 was the functional group at C-3. Specifically, the C-3 ketone in 2 was replaced by an acetoxy group in 3, which was evidenced by the lack of a carbonyl signal, while acetoxy group signals at δH 1.76 (3H, s) and δC 21.3 and 170.8 were present in the NMR spectrum of 3. The 1H-1H COSY correlations between H-2 and H-3 (δH 4.69), the HMBC correlations from H-3 to C-4 (δC 38.1), and the acetoxy carbonyl (δC 171.12) from 28-H3/29-H3 to C-3 (δC 80.9), C-4 (δC 38.4), and C-5 (δC 56.5) confirmed the above assignment (Figure 4). The large coupling constant of H-3 (dd, J = 11.8, 4.5 Hz) suggested that the acetoxyl group at C-3 was β-oriented. The 1H NMR spectrum of 3 also showed side chain signals at δH 1.09 (9H, s, H-26, H-27, and H-32) and at δH 5.04 and 4.91 (each 1H, brs, H-31a, b). The side chain structure was corroborated through HMBC correlations, including signals from H-21a (δH 5.00, brs) and H-21b (δH 4.91, brs) with carbons at δC 48.7, C-17 and δC 153.4, C-20. The de-shielded t-butyl singlet at δH 1.09 ppm further indicated the presence of an additional methyl group attached to C-25 and linked to the double bond [24]. These signals were consistent with a 24-methylene-25-methyl side chain [24]. The relative configurations of compound 3 were determined by T-ROESY spectroscopy. The T-ROESY correlations (Figure 4B) from 19-H3 to 18-H3, 29-H3, and H-11b indicated that they were co-facial, assigned as β-orientation. Consequently, the T-ROESY correlations from H-3 to 28-H3 and H-5 and H-5 to H-3, H-9, and 18-H3 revealed that they were α-oriented. The combined data suggested that compound 3 was 25-methyldammara-20,24-diene-3-β-yl-acetate.

Figure 4.

(A) Key HMBC correlations of compound 3. (B) T-ROESY correlations (C6D6) of compound 3.

4. Conclusions

This study represents the first comprehensive phytochemical investigation of Smilax canariensis, leading to the identification of both novel and known bioactive compounds, including triterpenes, sterols, flavonol glycosides, and other secondary metabolites. The isolation and structural elucidation of the newly discovered compounds—24,24-dimethyl-5α-cholesta-7,25-dien-3-one (1), 24-hydroxy-24-methyl-dammara-20,25-dien-3-one (2), and 3-acetyl-25-methyl-dammara-20,24-diene (3)—significantly expanded the known chemical diversity of this endemic species. These findings not only provide valuable insights into the metabolic pathways of S. canariensis but also highlight its potential as a source of bioactive molecules for pharmacological applications.

The presence of structurally diverse triterpenes and flavonol glycosides suggested that S. canariensis may possess significant bioactive properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and potential therapeutic effects, which merit further biological evaluation. In addition, the successful application of advanced spectroscopic techniques, such as 1D and 2D NMR, mass spectrometry, and chromatographic fractionation, highlighted the robustness of modern phytochemical analysis in uncovering novel natural products.

Future research should focus on evaluating the pharmacological potential of the identified compounds through in vitro and in vivo assays to determine their biological activities and possible medicinal applications. Furthermore, exploring the biosynthetic pathways of these secondary metabolites could provide a deeper understanding of the chemical ecology of S. canariensis and its adaptation to its unique island environment. This study underscores the importance of phytochemical investigations of endemic plant species as a means to discover new bioactive compounds with potential applications in medicine and biotechnology.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/separations12040074/s1, Figure S1: 1H NMR of 24, 24- dimethy-5α-cholesta-7, 25-dien-3-one (1); Figure S2: 13C NMR of 24, 24- dimethy-5α-cholesta-7, 25-dien-3-one (1); Figure S3: 13C-RMN DEPT of 24, 24- dimethy-5α-cholesta-7, 25-dien-3-one (1); Figure S4: HSQC RMN of 24, 24- dimethy-5α-cholesta-7, 25-dien-3-one (1); Figure S5: HMBC-RMN of 24, 24- dimethy-5α-cholesta-7, 25-dien-3-one (1); Figure S6: T-ROESY-RMN of 24, 24- dimethy-5α-cholesta-7, 25-dien-3-one (1); Figure S7: HR-ESI-MS of 24, 24- dimethy-5α-cholesta-7, 25-dien-3-one (1); Figure S8: HR-ESI-MS of 24, 24- dimethy-5α-cholesta-7, 25-dien-3-one (1); Figure S9: 1H NMR of 24-hydroxy-24-methyl-dammara-20, 25-dien-3-one (2); Figure S10: 13C RMN in C6D6 of 24-hydroxy-24-methyl-dammara-20, 25-dien-3-one (2); Figure S11: HSQC RMN of 24-hydroxy-24-methyl-dammara-20, 25-dien-3-one (2); Figure S12: HMBC RMN of 24-hydroxy-24-methyl-dammara-20, 25-dien-3-one (2); Figure S13: ROESY RMN of 24-hydroxy-24-methyl-dammara-20, 25-dien-3-one (2); Figure S14: HR-ESI-MS of 24-hydroxy-24-methyl-dammara-20, 25-dien-3-one (2); Figure S15: HR-ESI-MS of 24-hydroxy-24-methyl-dammara-20, 25-dien-3-one (2); Figure S16: 1H NMR in C6D6 of 3-acetyl-25-methyl-dammara-20,24-diene (3); Figure S17: 13C NMR in C6D6 of 3-acetyl-25-methyl-dammara-20, 24-diene (3); Figure S18: HSQC of 3-acetyl-25-methyl-dammara-20, 24-diene (3); Figure S19: HMBC of 3-acetyl-25-methyl-dammara-20, 24-diene (3); Figure S20: T-ROESY-RMN of 3-acetyl-25-methyl-dammara-20, 24-diene (3); Figure S21: HR-ESI-MS of 3-acetyl-25-methyl-dammara-20, 24-diene (3); Figure S22: HR-ESI-MS of 3-acetyl-25-methyl-dammara-20, 24-diene (3); Table S1: 1H (600 MHz), 13C (150 MHz), HSQC and HMBC NMR data of stigmast-4-en-3-one (4), in CDCl3.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G.D.; methodology, J.G.D.; formal analysis, J.G.D., S.V., D.G., P.P.d.P., D.D.D.; investigation, S.V., D.G.; resources, J.G.D. and D.D.D.; data curation, S.V., D.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G.D.; writing—review and editing, J.G.D. and D.D.D.; visualization, J.G.D.; supervision, J.G.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

D.D.D. acknowledges Cátedra Fundación CEPSA of the ULL, Cátedra de Medioambiente y Sostenibilidad (Cabildo de Tenerife-ULL), Fundación Ramón Areces, and the Ministry of Science and Innovation (project PID2022-142118OB-I00/AE/10.13039/501100011033/UE) for financial support, and Nanotec, INTech, Cabildo de Tenerife, and ULL for laboratory facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shao, B.; Guo, H.Z.; Cui, Y.J.; Ye, M.; Han, J.; Guo, D.A. Steroidal saponins from Smilax China and their anti-inflammatory activities. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.-W.; Zhang, H.; Guo, H.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J. Steroidal saponins from the genus Smilax and their biological activities. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2017, 7, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdala, S.; Martin-Herrera, D.; Benjumea, D.; Pérez-Paz, P. Diuretic activity of Smilax canariensis, an endemic Canary Island species. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 119, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, X. Phytochemical constituents and pharmacological activities of Smilax species: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 217, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdala, S.; Martin-Herrera, D.; Benjumea, D.; Pérez-Paz, P. Peripheral analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of Smilax canariensis in an animal model. Pharmacol. Pharm. 2015, 6, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, X. Recent advances in pharmacological research on Smilax species. Fitoterapia 2020, 146, 104697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Li, L.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Dai, Y.; Zhao, Y. Chemical constituents from the rhizomes of Smilax glabra and their antimicrobial activity. Molecules 2013, 18, 5265–5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, L.; Wang, J.; Tang, Y. Steroidal saponins with anti-inflammatory activity from Smilax china. Phytochemistry 2015, 109, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, J.G. Chemical composition of Hypericum Coadunatum Chr. from the Canary Islands. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1248, 131447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaluddin, F.; Mohameda, S.; Lajis, M.N. Hypoglycemic effect of Stigmast-4-en-3-one, from Parkia speciosa empty pods. Food Chem. 1995, 54, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiprono, P.C.; Kaberia, F.; Keriko, J.M.; Karanja, J.N. The in vitro anti-fungal and antibacterial activities of beta-sitosterol from Senecio lyratus (Asteraceae). Z. Naturforsch. 2000, 55c, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šmidrkal, J.; Harmatha, J.; Buděšínský, M.; Vokáč, K.; Zídek, Z.; Kmoníčková, E.; Merkl, R.; Filip, V. Modified approach for preparing (E)-stilbenes related to resveratrol and evaluating their potential immunobiological effects. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 2010, 75, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazuma, K.; Noda, N.; Suzuki, M. Malonylated flavonol glycosides from the petals of Clitoria Ternatea. Phytochemistry 2003, 62, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Alcantara Pinto, D.C.; Pitasse-Santos, P.; de Souza, G.A.; Castro, R.N.; de Lima, M.E.F. Peracetylation of polyphenols under rapid and mild reaction conditions. Nat. Prod. Res. 2023, 37, 2279–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayasinghe, U.L.B.; Balasooriya, B.A.I.S.; Bandara, A.G.D.; Fujimoto, Y. Glycosides from Grewia damine and Filicium decipiens. Nat. Prod. Res. Former. Nat. Prod. Lett. 2004, 18, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fier, P.S.; Maloney, K.M. Direct conversion of haloarenes to phenols under mild, transition-metal-free conditions. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 2244–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashparova, V.P.; Klushin, V.A.; Zhukova, I.Y.; Kashparov, I.S.; Chernysheva, D.V.; Il’Chibaeva, I.B.; Smirnova, N.V.; Kagan, E.S.; Chernyshev, V.M. A TEMPO-like nitroxide combined with an alkyl-substituted pyridine: An efficient catalytic system for the selective oxidation of alcohols with iodine. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 3517–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, T.; Tamura, T.; Sagawa, M.; Tamura, T.; Matsumoto, T. 4α-Methyl-5α-cholest-8(14)-en-3β-ol from the seeds of Capsicum annuum. Phytochemistry 1983, 22, 2621–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, T.; Tamura, T.; Sagawa, M.; Tamura, T.; Matsumoto, T. 4(R)-ethyllophenol from Solanum melongena seeds. Phytochemistry 1980, 19, 2491–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akihisa, T.; Ghosh, P.; Thakur, S.; Nagata, H.; Tamura, T.; Matsumoto, T. 24,24-Dimethyl-25-dehydrolophenol, a 4α-methylsterol from Clerodendrum inerme. Phytochemistry 1990, 29, 1639–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, B.C.; Araújo, B.Q.; Barros, E.D.S.; Freitas, S.D.M.; Maciel, D.S.A.; Ferreira, A.J.S.; Guadagnin, R.C.; Júnior, G.M.V.; Lago, J.H.G.; Chaves, M.H. Dammarane Triterpenoids from Carnauba, Copernicia prunifera (Miller) H. E. Moore (Arecaceae), Wax. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2017, 28, 1371–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathomwichaiwat, T.; Ochareon, P.; Soonthornchareonnon, N.; Ali, Z.; Khan, I.A.; Prathanturarug, S. Alkaline phosphatase activity-guided isolation of active compounds and new dammarane-type triterpenes from Cissus quadrangularis hexane extract. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 160, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjaneyulu, V.; Rao, G.S.; Connolly, J.D. Occurrence of 24-epimers of cycloart-25-ene-3-β, 24-diols in the stems of Euphorbia trigona. Phytochemistry 1985, 24, 1610–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Akihisa, T.; Tamura, T.; Matsumoto, T.; Yokota, T.; Nomura, T. 24-Methylene-25-methylcholesterol in Phaseolus vulgaris seed: Structural relation to brassinosteroids. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 629–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).