Abstract

In this paper, we consider a bilevel optimization problem as a task of finding the optimum of the upper-level problem subject to the solution set of the split feasibility problem of fixed point problems and optimization problems. Based on proximal and gradient methods, we propose a strongly convergent iterative algorithm with an inertia effect solving the bilevel optimization problem under our consideration. Furthermore, we present a numerical example of our algorithm to illustrate its applicability.

1. Introduction

Let H be a real Hilbert space and consider the constrained minimization problem:

where C is a nonempty closed convex subset of H and is a convex and continuously differentiable function. The gradient–projection algorithm (GPA, for short) is usually applied to solve the minimization problem (1) and has been studied extensively by many authors; see, for instance, [1,2,3] and references therein. This algorithm generates a sequence through the recursion:

where is the gradient of h, is the initial guess chosen arbitrarily from C, is a stepsize which may be chosen in different ways, and is the metric projection from H onto C. By the optimality condition on problem (1), it follows that

If is Lipschitz continuous and strongly monotone, i.e., there exists and such that for all ,

then the operator is a contraction provided that . Therefore, for , we can apply Banach’s contraction principle to get that the sequence defined by (2) converges strongly to the unique fixed point of (or the unique solution of the minimization (1)). Moreover, if you set in (1), then we have an unconstrained optimization problem, and hence the gradient algorithm

generates a sequence strongly convergent to the global minimizer point of h.

Consider the other most well-known problem called unconstrained minimization problem:

where H is a real Hilbert space and is a proper, convex, lower semicontinuous function. An analogous method for solving (3) with better properties is based on the notion of proximal mapping introduced by Moreau [4], i.e., the proximal operator of the function g with scaling parameter is a mapping given by

Proximal operators are firmly nonexpansive and the optimality condition of (3) is

Many properties of proximal operator can be found in [5] and the references therein. We know that the so called proximal point algorithm, i.e., is the most popular method solving optimization problem (3) (introduced by Martinet [6,7] and later by Rockafellar [8]).

The split inverse problem (SIP) [9] is formulated by linking problems installed in two different places X and Y connected by a linear transformations, i.e., SIP is a problem of finding a point in space X solving a problem IP1 installed in X and its image under linear transformation solves a problem IP2 installed in another space Y. The presence of step size choice dependent on operator norm is not quite recommended in the iterative method of solving SIPs, as it is not always easy to estimate the norm of an operator; see, for example, the Theorem of Hendrickx and Olshevsky in [10]. For example, in the early study of the iterative method of solving the split feasibility problem [11,12,13], the determination of the step-size depends on the operator norm (or at least estimate value of the operator norm) and this is not as easy of a task. To overcome this difficulty, Lopez et al. [14] introduced a new way of selecting the step sizes that the information of operator norm is not necessary for solving a split feasibility problem (SFP):

where C and Q are closed convex subsets of real Hilbert spaces and , respectively. To be precise, Lopez et al. [14] introduced an iterative algorithm that generates a sequence by

The parameter appeared in (4) by where , and .

A bilevel problem is a two-level hierarchical problem such that the solution of the lower level problem determines the feasible space of the upper level problem. In general, Yimer et al. [15] presented a bilevel problem as an archetypal model given by

where S is the solution set of the problem

According to [16], the bilevel problem (problem (5) and (6)) is a hierarchical game of two players as decision makers who make their decisions according to a hierarchical order. The problem is also called the leader’s and follower’s problem where the problem (5) is called the leader’s problem and (6) is called the follower’s problem, meaning, the first player (which is called the leader) makes his selection first and communicates it to the second player (the so-called follower). There are many studies for several type bilevel problems, see, for example, [15,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. The bilevel optimization problem is a bilevel problem when the hierarchical structure involves the optimization problem. Bilevel optimization problems have become an increasingly important class of optimization problems during the last few years and decades due their to vast application of solving the real life problems. For example, in toll-setting problem [25], in chemical engineering [26], in electricity markets [27], and in supply chain problems [28].

Motivated by the above theoretical results and inspired by the applicability of the bilevel problem, we consider the following bilevel optimization problem given by

where is a linear transformation, is convex function, is convex nonsmooth function, and for , is demimetric mapping and for , and and are two real Hilbert spaces.

For a real Hilbert space H, the mapping with is called -demimetric if and

The demimetric mapping is introduced by Takahashi [29] in a smooth, strictly convex and reflexive Banach space. For a real Hilbert space H, (8) is equivalent to the following:

and is a closed and convex subset of H [29]. The class of demimetric mappings contains the classes of strict pseudocontractions, firmly quasi-nonexpansive mappings, and quasi-nonexpansive mappings, see [29,30] and the references therein.

Assume that is the set of solutions of lower level problems of the bilevel optimization problem (7), that is,

Therefore, the bilevel optimization problem (7) is simply

where is given by (9). If , (identity operator), for all , the problem (7) is reduced to the bilevel optimization problem:

Bilevel problems like (10) have already been considered in the literature, for example, [23,31,32] for the case .

Note that, to the best of our knowledge, the bilevel optimization problem (7), with a finite intersection of fixed point sets of the broadest class of nonlinear mappings and finite intersection of minimize point sets of non-smooth functions as a lower level, has not been addressed before.

An inertial term is a two-step iterative method, and the next iterate is defined by making use of the previous two iterates. It is firstly introduced by Polyak [33] as an acceleration process in solving a smooth convex minimization problem. It is well known that combining algorithms with an inertial term speeds up or accelerates the rate of convergence of the sequence generated by the algorithm. In this paper, we introduce a proximal gradient inertial algorithm with a strong convergence result for approximating a bilevel optimization problem (7), where our algorithm is designed to address a way of selecting the step-sizes such that its implementation does not need any prior information about the operator norm.

2. Preliminary

Let C be a nonempty closed convex subset of a real Hilbert space H. The metric projection on C is a mapping defined by

For and , then if and only if

Let . Then,

- (a)

- T is L-Lipschitz if there exists such thatIf , then we call T a contraction with constant L. If , then T is called a nonexpansive mapping.

- (b)

- T is strongly monotone if there exists such thatIn this case, T is called -strongly monotone.

- (c)

- T is firmly nonexpansive ifwhich is equivalent toIf T is firmly nonexpansive, is also firmly nonexpansive.

Let H be a real Hilbert space. If is maximal monotone set-valued mapping, then we define the resolvent operator associated with G and as follows:

It is well known that is single-valued, nonexpansive, and 1-inverse strongly monotone (firmly nonexpansive). Moreover, if and only if is a fixed point of for all ; see more about maximal monotone and its associated resolvent operator and examples of maximal monotone operators in [34].

The subdifferential of a convex function at , denoted by , is defined by

If , f is said to be subdifferentiable at x. If the function f is continuously differentiable, then ; this is the gradient of f. If f is a proper, lower semicontinuous function, the subdifferential operator is a maximal monotone operator, and the proximal operator is the resolvent of the subdifferential operator (see, for example, in [5]), i.e.,

Thus, this results in proximal operators being firmly nonexpansive, and a point minimizes f if and only if

Definition 1.

Let H be a real Hilbert space. A mapping is called demiclosed if, for a sequence in H such that converges weakly to and , holds.

Lemma 1.

For a real Hilbert space H, we have

- (i)

- (ii)

- (iii)

Lemma 2.

[35] Let and be a sequences of nonnegative real numbers, be a sequences of real numbers such that

where and .

- (i)

- If for some , then is a bounded sequence.

- (ii)

- If and , then as .

Definition 2.

Let be a real sequence. Then, decreases at infinity if there exists such that for . In other words, the sequence does not decrease at infinity, if there exists a subsequence of such that for all .

Lemma 3.

[36] Let be a sequence of real numbers that does not decrease at infinity. In addition, consider the sequence of integers defined by

Then, is a nondecreasing sequence verifying , and, for all , the following two estimates hold:

Let D be a closed, convex subset of a real Hilbert space H and be a bifunction. Then, we say that g satisfies condition on D if the following four assumptions are satisfied:

- (a)

- , for all ;

- (b)

- g is monotone on D, i.e., , for all ;

- (c)

- for each ,

- (d)

- is convex and lower semicontinuous on D for each .

Lemma 4.

[37] (Lemma 2.12) Let g satisfy condition CO on D. Then, for each and , define a mapping (called resolvant of g), given by

Then, the following holds:

- (i)

- is single-valued;

- (ii)

- is a firmly nonexpansive, i.e., for all ,

- (iii)

- Fix, where Fix is the fixed point set of ;

- (iv)

- SEP is closed and convex.

3. Main Results

Our approach here is based on taking an existing algorithm on (1), (3), and the fixed point problem of nonlinear mapping, and determining how it can be used in the setting of bilevel optimization problem (7) considered in this paper. We present a self-adaptive proximal gradient algorithm with an inertial effect for generating a sequence that converges to the unique solution of the bilevel optimization problem (7) under the the following basic assumptions.

Assumption 1.

Assume that A, h, () and () in a bilevel optimization problem (7) satisfies

- A1.

- Each A is nonzero bounded linear operator;

- A2.

- h is proper, convex, continuously differentiable, and the gradient is a σ-strongly monotone operator and -Lipschitz continuous;

- A3.

- Each is -demimetric and demiclosed mapping for all ;

- A4.

- Each is a proper, convex, lower semicontinuous function for all .

Assumption 2.

Let and γ be a real number, and the real sequences (), (), , , satisfy the following conditions:

- (C1)

- (C2)

- , and .

- (C3)

- , and .

- (C4)

- (C5)

- , and .

- (C6)

- and .

- (C7)

- and .

Assuming that the Assumption 1 is satisfied, the solution set of the lower level problem of (7) is nonempty, and, for each , define by

Note that, from Aubin [38], if is indicator function, then is convex, w-lsc and differentiable for each , and is given by

Next, we present and analyze the strong convergence of Algorithm 1 using and by assuming that is differentiable.

| Algorithm 1: Self-adaptive proximal gradient algorithm with inertial effect. | |

| Initialization: Let the real number and the real sequences (), (), , , and satisfy the conditions in Assumption 2 (C1)–(C7). Choose arbitrarily and proceed with the following computations:

| |

Remark 1.

From Condition (C7) and Step 1 of Algorithm 1, we have that

Since is bounded, we also have Note that Step 1 of Algorithm 1 is easily implemented in numerical computation since the value of is a priori known before choosing .

Note that: Let , where . Then, we have

where for . Therefore, for , the mapping is a contraction mapping with constant . Consequently, the mapping is also a contraction mapping with constant , i.e., Hence, by the Banach contraction principle, there exists a unique element such that . Clearly, and we have

Lemma 5.

For the sequences , and generated by Algorithm 1 and for , we have

- (i)

- (ii)

Proof.

Theorem 1.

The sequence generated by Algorithm 1 converges strongly to the solution of problem (7).

Proof.

Claim 1: The sequences , and are bounded.

Let . Now, from the definition of , we get

Using (16) and the definition of , we get

Observe that, by (C6) and Remark 1, we see that

Let

Then, (17) becomes

Thus, by Lemma 2, the sequence is bounded. As a consequence, , and are also bounded.

Claim 2: The sequence converges strongly to , where .

Now,

From Lemma 1 , we have

From (18) and (19) and since , we get

Using the definition of and Lemma 1, we have

Lemma 5 together with (20) and (21) give

Since the sequence and are bounded, there exists such that for all . Thus, from (22), we obtain

Let us distinguish the following two cases related to the behavior of the sequence where .

Case 1. Suppose the sequence decreases at infinity. Thus, there exists such that for . Then, converges and as .

From (23), we have

and

Since () and using (C5), (C6), and Remark 1 (noting , , is bounded and ); we have, from (24) and (25),

In view of (26) and conditions (C2)–(C6), we have

for all and for all .

Using (26), we have

Similarly, from (26), we have

Using the definition of and Remark 1, we have

Moreover, using the definiton of and boundedness of and together with condition (C5), we have

Therefore, from (28)–(31), we have

For each , are Lipschitz continuous with constant . Therefore, the sequence is bounded sequence for each , and hence, using (27), we have for all .

Let p be a weak cluster point of ; there exists a subsequence of such that as . Since as (from (30)), we have as . Hence, using , (27) and demiclosedness of , we have for all .

Moreover, since as (from (29) and (30)), we have as . Hence, the weak lower-semicontinuity of implies that

for all . That is, for all . Thus, .

We now show that . Indeed, since and, from above, p is a weak cluster point of , i.e., , and , we obtain that

Since from (32), from (33), we obtain

Now, using Lemma 5 (ii), we get

Therefore, from (35), we have

Combining (36) and

it holds that

Since is bounded, there exists such that for all . Thus, in view of (37), we have

where and

From (C5), Remark 1 and (34), we have and . Thus, using Lemma 2 and (38), we get as . Hence, as .

Case 2. Assume that does not decrease at infinity. Let be a mapping for all (for some large enough) defined by

By Lemma 3, is a nondecreasing sequence, as and

In view of for all and (23), we have for all

Similarly, from (23), we have for all

Thus, for (40) and (41) together with (C3)–(C6) and Remark 1, we have for each and ,

Using a similar procedure as above in Case 1, we have

By the similar argument as above in Case 1, since is bounded, there exists a subsequence of which converges weakly to and this gives . Thus, from (38), we have

where and

Using for all and , the last inequality gives

Since , we obtain Moreover, since , we have Thus, together with , gives . Therefore, from (39), we obtain , that is, as . □

For , we have the following results solving the bilevel problem (10):

Corollary 1.

If , the sequence generated by

converges strongly to the solution the bilevel problem (10) if , and are real sequences such that

- (C1)

- , and .

- (C2)

- and .

- (C3)

- where for .

4. Applications

4.1. Application to the Bilevel Variational Inequality Problem

Let and be two real Hilbert spaces. Assume that is -Lipschitz continuous and -strongly monotone on , is a bounded linear operator, is a proper, convex, lower semicontinuous function for all , and is -demimetric and demiclosed mapping for all . Then, replacing by F in Algorithm 1, we obtain strong convergence for an approximation of a solution of the bilevel variational inequality problem

where is the solution set of

4.2. Application to a Bilevel Optimization Problem with a Feasibility Set Constraint, Inclusion Constraint, and Equilibrium Constraint

Let and be two real Hilbert spaces, be a linear transformation and be proper, convex, continuously differentiable, and the gradient is -strongly monotone operator and -Lipschitz continuous.

Now, consider the bilevel optimization problem with a feasibility set constraint

where each is a closed convex subset of for . Replacing for all and by projection mapping in Algorithm 1, we obtain strong convergence for an approximation of the solution of the bilevel problem (44).

Consider the bilevel optimization problem with inclusion constraint

where is maximal monotone mapping for . Setting for all and, replacing the proximal mapping in Algorithm 1 by the resolvent operators (for ), and following the method of proof in theorems, we obtain a strong convergence result for approximation of the solution of the bilevel problem (45).

Consider the bilevel optimization problem with equilibrium constraint

where is a bifunction and each satisfies condition on . We have strong convergence results solving (46) by setting for all and replacing the proximal mappings by the resolvent operators in Algorithm 1 (see (11) and properties of it in Lemma 4 (i)–(iv)).

5. Numerical Example

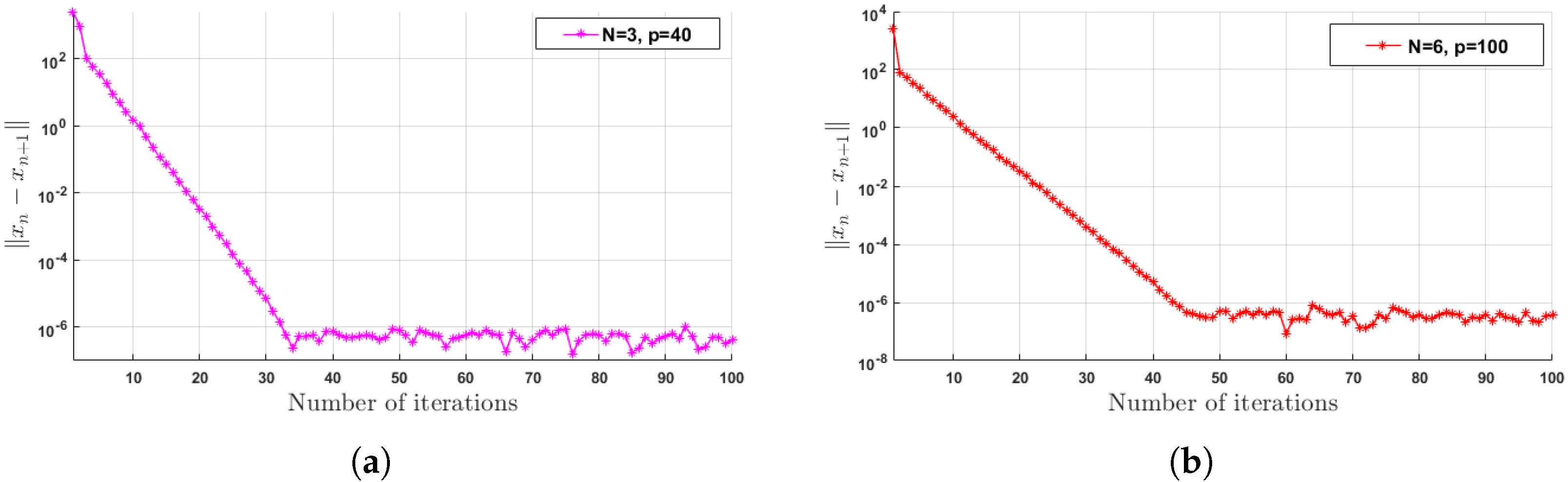

Taking the bilevel optimization problem (7) for , , the linear transformations are given by , where is matrix, and for , , we have

where D and B are invertible symmetric positive semidefinite and matrix, respectively, , , is the Euclidean norm in , is the Euclidean norm in , and for .

Here, where and hence the gradient is -Lipschitz. Thus, the gradient is 1-strongly monotone and ()-Lipschitz. We choose .

Now, for , the proximal , and is given by

and where

We consider for , for and , where is identity matrix. The parameters are chosen are for , for , , , and .

For the purpose of testing our algorithm, we took the following data:

- D and B are randomly generated invertible symmetric positive semidefinite matrices, respectively.

- and are randomly generated starting points.

- The stopping criteria .

Table 1 and Table 2 and Figure 1 illustrate the numerical results of our algorithms for this example under the parameters and data given above and for . The number of iterations (Iter(n)), CPU time in seconds (CPU(s)), and the error , where is the solution set of the bilevel optimization problem ( here in this example), are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Performance of Algorithm 1 for different N and different dimensions with .

Table 2.

Performance of Algorithm 1 for and different with .

Figure 1.

Algorithm 1 for different N and different dimensions .

We now compare our algorithm for different , i.e., for non-inertial accelerated case () and for inertial accelerated case (). For the non-inertial accelerated case, we just simply take , and, for the inertial accelerated case, we take a very small with so that . Numerical comparisons of our proposed algorithm with inertial version () and its non-inertial version () are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Performance of Algorithm 1 for for different dimensions , with .

Remark 2.

Table 1 and Table 2 show that the CPU time and number of iterations of the algorithm increase linearly with the size or complexity of the problem (with the size of dimension p and q, number of mappings R and N, and number of functions M). From Table 3, we can see that our algorithm has a better performance for the stepsize choice . This implies that the inertial version of our algorithm has a better convergence analysis.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have proposed the problem of minimizing a convex function over the solution set of the split feasiblity problem of fixed point problems of demimetric mappings and constrained minimization problems of nonsmooth convex functions. We have showed that this problem can be solved by proximal and gradient methods where the gradient method is used for an upper level problem and the proximal method is used for a lower level problem. Most of the standard bilevel problems are particular cases of our framework.

Author Contributions

S.E.Y., P.K. and A.G.G. contributed equally in this research paper particularly on the conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, resource, and writing and preparing the original draft of the manuscript; however, P.K. fundamentally plays a great role in supervision and funding acquisition as well. Moreover, A.G.G. particularly wrote the code and run the algorithm in the MATLAB program. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was received from the Petchra Pra Jom Klao Ph.D. Research Scholarship from King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi (KMUTT) and Theoretical and Computational Science (TaCS) Center. Moreover, Poom Kumam was supported by the Thailand Research Fund and the King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi under the TRF Research Scholar Grant No.RSA6080047. The Rajamangala University of Technology Thanyaburi (RMUTTT) (Grant No. NSF62D0604).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support provided by the Center of Excellence in Theoretical and Computational Science (TaCS-CoE), KMUTT. Seifu Endris Yimer is supported by the Petchra Pra Jom Klao Ph.D. Research Scholarship from King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi (Grant No.9/2561).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Su, M.; Xu, H.K. Remarks on the gradient-projection algorithm. J. Nonlinear Anal. Optim. 2010, 1, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.K. Averaged mappings and the gradient-projection algorithm. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2011, 150, 360–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceng, L.C.; Ansari, Q.H.; Yao, J.C. Some iterative methods for finding fixed points and for solving constrained convex minimization problems. Nonlinear Anal. Theor. 2011, 74, 5286–5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockafellar, R.T.; Wets, R.J. Variational Analysis; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bauschke, H.H.; Combettes, P.L. Convex Analysis and Monotone Operator Theory in Hilbert Spaces; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Martinet, B. Brève communication. Régularisation d’inéquations variationnelles par approximations successives. Revue Française d’Informatique et de Recherche Opérationnelle Série Rouge 1970, 4, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinet, B. Détermination approchée d’un point fixe d’une application pseudo-contractante. CR Acad. Sci. Paris 1972, 274, 163–165. [Google Scholar]

- Rockafellar, R.T. Monotone operators and the proximal point algorithm. SIAM J. Control Optim. 1976, 14, 877–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Censor, Y.; Gibali, A.; Reich, S. Algorithms for the split variational inequality problem. Numer. Algorithms 2012, 59, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickx, J.M.; Olshevsky, A. Matrix p-Norms Are NP-Hard to Approximate If p ≠ 1,2,∞. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. A 2010, 31, 2802–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Censor, Y.; Elfving, T. A multiprojection algorithm using Bregman projections in a product space. Numer. Algorithms 1994, 8, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, B.; Xiu, N. A note on the CQ algorithm for the split feasibility problem. Inverse Probl. 2005, 21, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C. Iterative oblique projection onto convex sets and the split feasibility problem. Inverse Probl. 2002, 18, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, G.; Martín-Márquez, V.; Wang, F.; Xu, H.K. Solving the split feasibility problem without prior knowledge of matrix norms. Inverse Probl. 2012, 28, 085004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimer, S.E.; Kumam, P.; Gebrie, A.G.; Wangkeeree, R. Inertial Method for Bilevel Variational Inequality Problems with Fixed Point and Minimizer Point Constraints. Mathematics 2019, 7, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempe, S.; Kalashnikov, V.; Pérez-Valdés, G.A.; Kalashnykova, N. Bilevel programming problems. In Energy Systems; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Anh, T.V. Linesearch methods for bilevel split pseudomonotone variational inequality problems. Numer. Algorithms 2019, 81, 1067–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, T.V.; Muu, L.D. A projection-fixed point method for a class of bilevel variational inequalities with split fixed point constraints. Optimization 2016, 65, 1229–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuying, T.; Van Dinh, B.; Plubtieng, S. Extragradient subgradient methods for solving bilevel equilibrium problems. J. Inequal. Appl. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehu, Y.; Vuong, P.T.; Zemkoho, A. An inertial extrapolation method for convex simple bilevel optimization. Optim. Method Softw. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabach, S.; Shtern, S. A first order method for solving convex bilevel optimization problems. SIAM J. Optimiz. 2017, 27, 640–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boţ, R.I.; Csetnek, E.R.; Nimana, N. An inertial proximal-gradient penalization scheme for constrained convex optimization problems. Vietnam J. Math. 2018, 46, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solodov, M. An explicit descent method for bilevel convex optimization. J. Convex Anal. 2007, 14, 227. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.S.; Quan, J.; Liu, J. Feasible iterative algorithms and strong convergence theorems for bi-level fixed point problems. J. Nonlinear Sci. Appl. 2016, 9, 1515–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Didi-Biha, M.; Marcotte, P.; Savard, G. Path-based formulations of a bilevel toll setting problem. In Optimization with Multivalued Mappings; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mohideen, M.J.; Perkins, J.D.; Pistikopoulos, E.N. Optimal design of dynamic systems under uncertainty. AIChE J. 1996, 42, 2251–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fampa, M.; Barroso, L.A.; Candal, D.; Simonetti, L. Bilevel optimization applied to strategic pricing in competitive electricity markets. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2008, 39, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, H.I.; Galé, C.; Oliveros, M.J. Bilevel model for production–distribution planning solved by using ant colony optimization. Comput. Oper. Res. 2011, 38, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Takahashi, W. The split common null point problem and the shrinking projection method in Banach spaces. Optimization 2016, 65, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y. Iterative methods for fixed point problems and generalized split feasibility problems in Banach spaces. J. Nonlinear Sci. Appl. 2018, 11, 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabot, A. Proximal point algorithm controlled by a slowly vanishing term: Applications to hierarchical minimization. SIAM J. Optim. 2005, 15, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helou, E.S.; Simões, L.E. ϵ-subgradient algorithms for bilevel convex optimization. Inverse Probl. 2017, 33, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyak, B.T. Some methods of speeding up the convergence of iteration methods. USSR Comput. Math. Math. Phys. 1964, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, B. Which fixed point does the iteration method select? In Recent Advances in Optimization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 154–167. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.K. Iterative algorithms for nonlinear operators. J. Lond. Math. Soc. 2002, 66, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maingé, P.E. Strong convergence of projected subgradient methods for nonsmooth and nonstrictly convex minimization. Set Valued Anal. 2008, 16, 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combettes, P.L.; Hirstoaga, S.A. Equilibrium programming in Hilbert spaces. J. Nonlinear Convex Anal. 2005, 6, 117–136. [Google Scholar]

- Aubin, J.P. Optima and Equilibria: An Introduction to Nonlinear Analysis; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).