A Bibliometric Analysis on the Early Works of Dental Anxiety

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

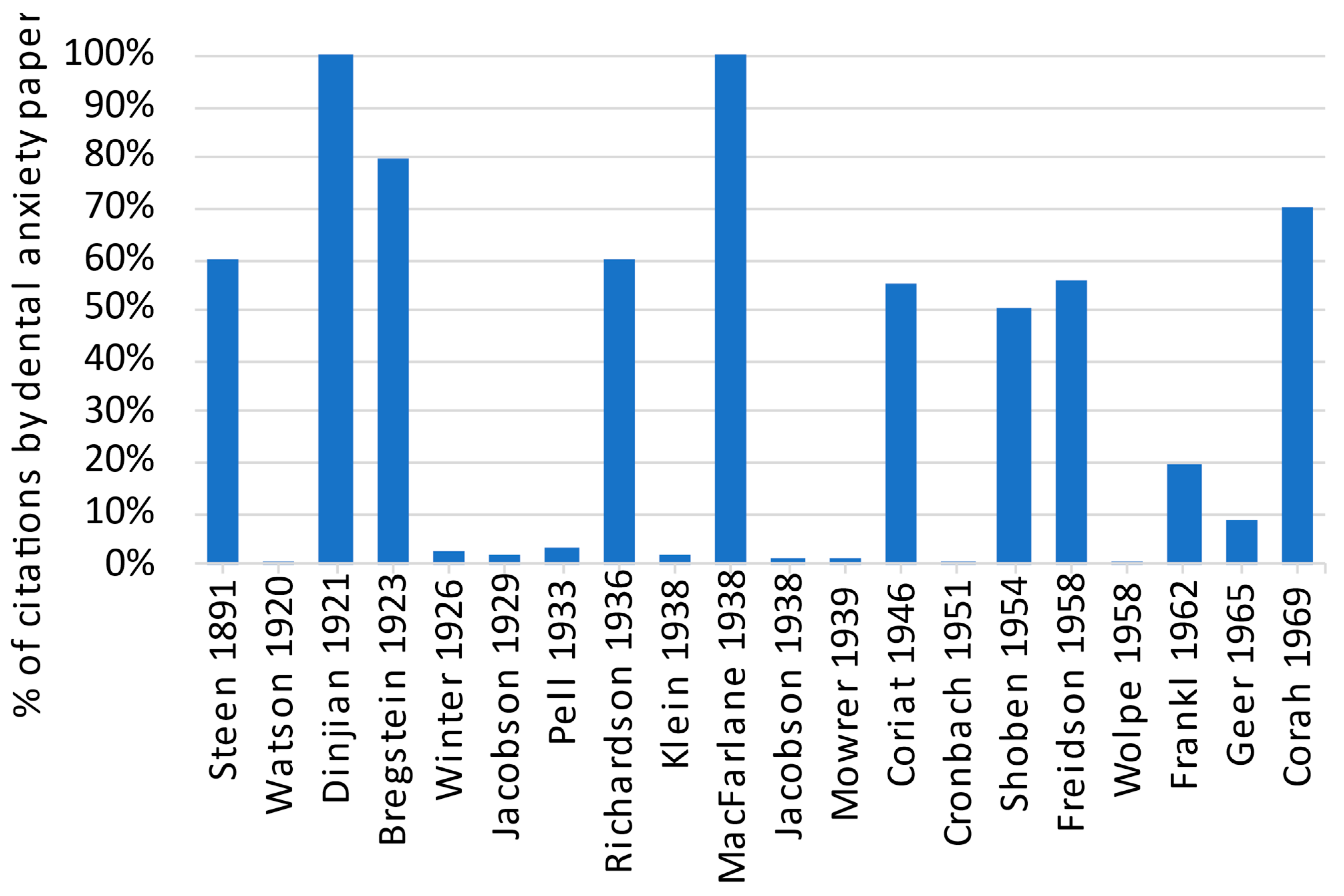

| Year | Reference Number | Title | Number of Citations within the Dataset | Percentage of Citations Made to References of That Year | Relevance (V, Relevant; X, Irrelevant; ?, Unclear) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1891 | [26] | Our relation to children | 3 | 100.0% | (?) Potentially relevant to child dental anxiety (no access to the publication). |

| 1920 | [35] | Conditioned emotional reactions | 3 | 75.0% | (X) Reported experimental findings of conditioned fear responses in a male infant. Conditions were not related to dental anxiety (e.g., confronted him suddenly with a white rat, rabbit, dog, etc.). |

| 1921 | [24] | The psychic factor in dental practice | 3 | 100.0% | (?) Potentially relevant to dental anxiety (no access to the publication). |

| 1923 | [20] | Psychology in dentistry | 4 | 57.1% | (V) Briefly commented that dental fear could be unexplainable, anticipatory of pain and serious problems, and related to confidence towards the dentist. |

| 1926 | [19] | The principles of exodontia as applied to the impacted third molar (Book) | 6 | 75.0% | (X) Introduced a classification for impacted third molars. |

| 1929 | [36] | Progressive relaxation (1st ed; Book) | 5 | 50.0% | (X) Discussed progressive muscle relaxation, a strategy that may be adopted to manage anxiety. |

| 1933 | [18] | Impacted mandibular third molars: classification and modified techniques for removal | 12 | 100.0% | (X) Introduced a classification for impacted third molars. |

| 1936 | [25] | Fear—a dental problem | 3 | 50.0% | (?) Potentially relevant to dental anxiety (no access to the publication). |

| 1938 | [37] | Progressive relaxation (2nd ed; Book) | 8 | 44.4% | (X) Discussed progressive muscle relaxation, a strategy that may be adopted to manage anxiety. |

| [38] | Studies on dental caries: I. Dental status and dental needs of elementary school children | 4 | 22.2% | (X) Investigated dental caries and dental needs of elementary school children. | |

| [21] | The psychology of fear in dentistry | 3 | 16.7% | (V) Explained in detail that dental fear could be attributable to eight aspects, from prior unpleasant dental experience to symbolic associations. | |

| 1939 | [39] | A stimulus-response analysis of anxiety and its role as a reinforcing agent | 5 | 50.0% | (X) Reviewed the literature and argued that anxiety should be a learned (conditioned) response anticipatory of injury or pain. Moreover, anxiety could be irrationally disproportionate to the extent of danger. |

| 1946 | [7] | Dental anxiety; fear of going to the dentist | 11 | 73.3% | (V) Articulated dental anxiety from a psychoanalysis view. It could be anticipatory of pain and danger. It could also be neurotic, meaning unconsciously perceiving the treatment or removal of a tooth as symbolic castration. |

| 1951 | [40] | Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests | 16 | 64.0% | (X) Introduced a test score reliability coefficient known as Cronbach’s alpha. |

| 1954 | [23] | An empirical study of the etiology of dental fears | 51 | 75.0% | (V) Performed semi-structured interviews on 30 adults. Half of them displayed intense emotional patterns in the dental office and formed the fearful group, and the other half formed the control group. Results showed that the fearful group had a significantly higher ratio of unfavorable family dental experience and attitude toward dentistry. No significant differences were found for pain tolerance, traumatic healthcare experience, general anxiety level, trouble with authority, appearance, and psychoanalytic factors (orality and dependency). |

| 1958 | [41] | The public looks at dental care | 32 | 44.4% | (X) Reported a public health survey. Fear of dentists and pain were among the commonest reasons for both not seeing a dentist more often and not having needed dental care. |

| [42] | Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition (Book) | 16 | 22.2% | (X) Introduced reciprocal inhibition. By teaching patients to relax and confront the fear via imagery manipulations in behavioral treatment, the new behavior could replace the old one. | |

| 1962 | [22] | Should the parent remain with the child in the dental operatory? | 71 | 53.8% | (V) Introduced Frankl’s behavior rating scale to assess child dental anxiety. |

| 1965 | [43] | The development of a scale to measure fear | 48 | 49.5% | (X) Introduced a fear scale, Fear Survey Schedule-II, to measure fear in general. |

| 1966 | NA | ||||

| 1969 | [15] | Development of a Dental Anxiety Scale | 547 | 71.0% | (V) Introduced the well-known Corah’s Dental Anxiety Scale. |

4. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Armfield, J.M. How do we measure dental fear and what are we measuring anyway? Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2010, 8, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Silveira, E.R.; Cademartori, M.G.; Schuch, H.S.; Armfield, J.A.; Demarco, F.F. Estimated prevalence of dental fear in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. 2021, 108, 103632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perazzo, M.F.; Otoni, A.L.C.; Costa, M.S.; Granville-Granville, A.F.; Paiva, S.M.; Martins-Júnior, P.A. The top 100 most-cited papers in Paediatric Dentistry journals: A bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2019, 29, 692–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, L.; Freeman, R.; Humphris, G. Why are people afraid of the dentist? Observations and explanations. Med. Princ. Pract. 2014, 23, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabé, E.; Humphris, G.; Freeman, R. The social gradient in oral health: Is there a role for dental anxiety? Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2017, 45, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facco, E.; Zanette, G. The odyssey of dental anxiety: From prehistory to the present. A narrative review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coriat, I.H. Dental anxiety: Fear of going to the dentist. Psychoanal. Rev. 1946, 33, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Corah, N.L.; Gale, E.N.; Illig, S.J. Assessment of a dental anxiety scale. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1978, 97, 816–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thor, A.; Marx, W.; Leydesdorff, L.; Bornmann, L. Introducing CitedReferencesExplorer (CRExplorer): A program for reference publication year spectroscopy with cited references standardization. J. Informetr. 2016, 10, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, W.; Bornmann, L. Tracing the origin of a scientific legend by reference publication year spectroscopy (RPYS): The legend of the Darwin finches. Scientometrics 2014, 99, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, W.; Bornmann, L.; Barth, A.; Leydesdorff, L. Detecting the historical roots of research fields by reference publication year spectroscopy (RPYS). J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2014, 65, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, K.B.; Bornmann, L. Philosophy of science viewed through the lense of “Referenced Publication Years Spectroscopy”(RPYS). Scientometrics 2015, 102, 1987–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, A.W.K. Identification of seminal works that built the foundation for functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of taste and food. Curr. Sci. 2017, 113, 1225–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, A.W.K.; Wong, N.S.M.; Leung, Y.Y. Are coronectomy studies being cited? A bibliometric study. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2018, 10, e12366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corah, N.L. Development of a dental anxiety scale. J. Dent. Res. 1969, 48, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornmann, L.; Haunschild, R.; Leydesdorff, L. Reference publication year spectroscopy (RPYS) of Eugene Garfield’s publications. Scientometrics 2018, 114, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, A.W.K.; Wong, N.S.M. The historical roots of visual analog scale in psychology as revealed by reference publication year spectroscopy. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pell, G.J.; Gregory, B.T. Impacted mandibular third molars: Classification and modified techniques for removal. Dent. Dig. 1933, 39, 330–338. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, G. The Principles of Exodontia as Applied to the Impacted Third Molars: A Complete Treatise on the Operative Technic with Clinical Diagnoses and Radiographic Interpretations; American Medical Book Co.: St. Louis, MI, USA, 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Bregstein, S. Psychology in dentistry. Dent. Dig. 1923, 29, 387–389. [Google Scholar]

- MacFarlane, D.W. The psychology of fear in dentistry. Br. Dent. J. 1938, 65, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Frankl, S.N. Should the parent remain with the child in the dental operatory? J. Dent. Child. 1962, 29, 150–163. [Google Scholar]

- Shoben, E.J.; Borland, L. An empirical study of the etiology of dental fears. J. Clin. Psychol. 1954, 10, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinjian, M. The psychic factor in dental practice. Dent. Surg. 1921, 17, 471–475. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, F. Fear-a dental problem. Oral Hyg. 1936, 26, 344–349. [Google Scholar]

- Steen, W. Our relation to children. Dent. Rev. 1891, 5, 534–537. [Google Scholar]

- Kuscu, O.; Caglar, E.; Kayabasoglu, N.; Sandalli, N. Preferences of dentist’s attire in a group of Istanbul school children related with dental anxiety. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2009, 10, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themessl-Huber, M.; Freeman, R.; Humphris, G.; Macgillivray, S.; Terzi, N. Empirical evidence of the relationship between parental and child dental fear: A structured review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2010, 20, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townend, E.; Dimigen, G.; Fung, D. A clinical study of child dental anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 2000, 38, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. Dental anxiety: A multifactorial aetiology. Br. Dent. J. 1985, 159, 406–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M.O. Dental anxiety: Detection and management. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2010, 18, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, E.; Karacay, S. Evaluation of anxiety level changes during the first three months of orthodontic treatment. Korean J. Orthod. 2012, 42, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, R. A psychodynamic theory for dental phobia. Br. Dent. J. 1998, 184, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson III, W. A cognitive-behavioral treatment for disproportionate dental anxiety and pain: A case study. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 1981, 10, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.B.; Rayner, R. Conditioned emotional reactions. J. Exp. Psychol. 1920, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, E. Progressive Relaxation, 1st ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, E. Progressive Relaxation, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, H.; Palmer, C.E.; Knutson, J.W. Studies on dental caries: I. Dental status and dental needs of elementary school children. Public Health Rep. (1896–1970) 1938, 53, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowrer, O.H. A stimulus-response analysis of anxiety and its role as a reinforcing agent. Psychol. Rev. 1939, 46, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freidson, E.; Feldman, J.J. The public looks at dental care. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1958, 57, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolpe, J. Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Geer, J.H. The development of a scale to measure fear. Behav. Res. Ther. 1965, 3, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.; Maguire, A.; Ryan, V.; Wilson, N.; Innes, N.P.; Clarkson, J.E.; McColl, E.; Marshman, Z.; Robertson, M.; Abouhajar, A. The FICTION trial: Child oral health-related quality of life and dental anxiety across three treatment strategies for managing caries in young children. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2020, 48, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, N.S.M.; Yeung, A.W.K.; McGrath, C.P.; Leung, Y.Y. Qualitative Evaluation of YouTube Videos on Dental Fear, Anxiety and Phobia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, N.S.M.; Yeung, A.W.K.; Li, K.Y.; Mcgrath, C.P.; Leung, Y.Y. Non-pharmacological interventions for reducing fear and anxiety in patients undergoing third molar extraction under local anesthesia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lal, A.; Saeed, S.; Ahmed, N.; Alam, M.K.; Maqsood, A.; Zaman, M.U.; Abutayyem, H. Comparison of Dental Anxiety While Visiting Dental Clinics before and after Getting Vaccinated in Midst of COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines 2022, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, L.D.; Hovey, J.D.; Chacon, K.; Ollendick, T.H. Dental anxiety: An understudied problem in youth. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 55, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stouthard, M.E.; Mellenbergh, G.J.; Hoogstraten, J. Assessment of dental anxiety: A facet approach. Anxiety Stress Coping 1993, 6, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freud, S. The Interpretation of Dreams; Franz Deuticke, Leipzig & Vienna: Vienna, Austria, 1900. [Google Scholar]

- Coriat, I.H. A note on symbolic castration in prehistoric man. Int. J. Psychoanal. 1931, 12, 492–495. [Google Scholar]

- Capps, D.; Carlin, N. Sublimation and symbolization: The case of dental anxiety and the symbolic meaning of teeth. Pastor. Psychol. 2011, 60, 773–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capps, D.; Carlin, N. The tooth fairy: Psychological issues related to baby tooth loss and mythological working through. Pastor. Psychol. 2014, 63, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, A.W.K. Is the influence of Freud declining in psychology and psychiatry? A bibliometric analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.K. On the Shoulders of Giants: A Shandean Postscript; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, A.W.K. The Diagnostic Relevance and Interfaces Covered by Mach Band Effect in Dentistry: An Analysis of the Literature. Healthcare 2022, 10, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yeung, A.W.K. A Bibliometric Analysis on the Early Works of Dental Anxiety. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11020036

Yeung AWK. A Bibliometric Analysis on the Early Works of Dental Anxiety. Dentistry Journal. 2023; 11(2):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11020036

Chicago/Turabian StyleYeung, Andy Wai Kan. 2023. "A Bibliometric Analysis on the Early Works of Dental Anxiety" Dentistry Journal 11, no. 2: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11020036