Participatory Methods in Food Behaviour Research: A Framework Showing Advantages and Disadvantages of Various Methods

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Participatory Research Methods and Applications in Food Behaviour Research

2.1. A Structured Verview

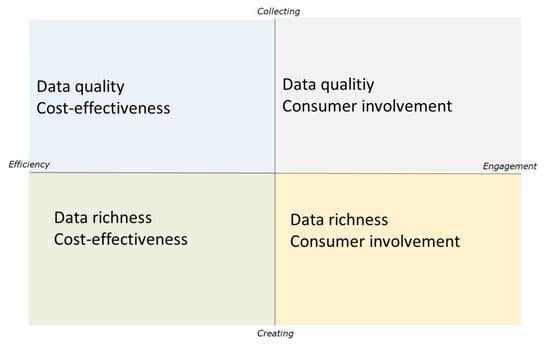

2.2. Dimensions of Participation in Food Behaviour Research

2.2.1. Quadrant 1: Efficiency and Collecting

2.2.2. Quadrant II: Efficiency and Creating

2.2.3. Quadrant III: Engagement and Collecting

2.2.4. Quadrant IV: Engagement and Creating

3. Applying Participation in Food Behaviour Research: Advantages and Disadvantages

3.1. An Overview of Advantages and Disadvantages from the General Literature

3.1.1. Category 1: Cost-Effectiveness

3.1.2. Category 2: Involvement

3.1.3. Category 3: Data Richness

3.1.4. Category 4: Data Quality

3.2. An Overview of Specific Advantages and Disadvantages Mentioned in the Food Behaviour Research, for Each of the Quadrants

3.2.1. Efficiency and Collecting (Citizen Science)

3.2.2. Efficiency and Creating (Crowd Science)

3.2.3. Engagement and Collecting (Photovoice)

3.2.4. Engagement and Creating (PAR)

3.2.5. Overview of Advantages and Disadvantages Relating to Method, Quadrant and Area

4. Discussion

4.1. Making a Balanced Choice

4.2. Current Use of Participatory Methods in Food Behaviour Research

4.3. Participatory Methods in Future Research: A Research Agenda

4.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dimension | Participation Strategy | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efficiency and collecting | Citizen science | Cost-effectiveness ⮚ Combining real world context, time series and socio-psychological insights in one application [1,2,24] Data quality ⮚ A low burden for citizens [24] ⮚ A low recall bias [24] ⮚ An aggregated view of food consumption trends [24] | Cost-effectiveness ⮚ Managing large amounts of data [24] Data quality ⮚ Wrongful app-use, reducing data quality [14] Data richness ⮚ Reduced representativeness due to attracting highly motivated citizens [14] Involvement ⮚ Citizens need to be motivated to use the tool (correctly) [14] |

| Efficiency and creating | Crowd science | Cost-effectiveness ⮚ A larger quantity of labour inputs [45] ⮚ The opportunity for future scientists to build upon prior work [45] Data richness ⮚ Access to rare and specialized skills [45] ⮚ A diversity in knowledge [45] Involvement ⮚ Being part of a community and the opportunity to contribute to science [45] Data quality ⮚ Internal verification of the results [45] | Cost-effectiveness ⮚ Integrating contributions is challenging [45] Data richness ⮚ Dealing with different motivations contributors might have [45] Involvement ⮚ The need for organizational methods to match projects and contributors and dividing tasks ⮚ Motivating contributors to increase the work they put in [45] |

| Engagement and collecting | Photovoice | Involvement ⮚ Involves citizens leading to a partnership [10] Data quality ⮚ High quality dataset revealing the real and experienced environment where dietary behaviours are enacted [30] Data richness ⮚ Gaining first-hand knowledge with interpretations that represent community perspectives [10] Cost-effectiveness ⮚ Gaining a partnership that can facilitate the development of future interventions [10] | Involvement ⮚ Establishing community connections and recruiting volunteers is difficult [10] Data quality ⮚ The data might not cover all aspects of interest [30] Data richness ⮚ Potentially small sample sizes with unequal representation [10] ⮚ Limited transferability of findings, due to localized data collection, purposive sampling and participant self-selection [30] Cost-effectiveness ⮚ Not all the data collected can always be included in the data analysis [10] |

| Engagement and creating | Participatory action research and CBPR* | Participatory action research Involvement ⮚ Equal power relations between researcher and researched [9] ⮚ Ethical form of research [9] Data richness ⮚ Addressing problems, generating knowledge and finding solutions together [9] ⮚ Citizens open up more, resulting in in depth and rich data that are substantial and emotionally nuanced [9] CBPR* Involvement ⮚ Applicable research findings can be put into practice in specific communities directly [13] Data richness ⮚ A deep understanding of a community’s unique circumstances [25,33,34] ⮚ The unique perspective of citizens on the research problem and process [13] | Participatory action research Involvement ⮚ Difficulty establishing a genuinely collaborative project [9] ⮚ Lack of common ground between research and practice [9] ⮚ Unrealistic citizen expectations about the research [9] ⮚ Time-consuming and expensive [9] ⮚ Receiving funding can be difficult [9] Data richness ⮚ Potentially unrepresentative samples [9] CBPR Involvement ⮚ Inconsistent attendance by citizens [25] ⮚ Long recruitment periods [25] Data richness ⮚ Small sample sizes [25] ⮚ Participants experiencing fatigue [25] Data quality ⮚ Lower research validity and reliability [13] ⮚ Less elaborate survey instruments [13] ⮚ Changes in program components [25] ⮚ Less control over data collection [13] |

References

- Kimura, A.H.; Kinchy, A. Citizen Science: Probing the Virtues and Contexts of Participatory Research. Engag. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2016, 2, 331–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scheliga, K.; Friesike, S.; Puschmann, C.; Fecher, B. Setting up crowd science projects. Public Underst. Sci. 2018, 27, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voorberg, W.; Bekkers, V.; Tummers, L. A Systematic Review of Co-Creation and Co-Production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 1333–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Florin, P.; Wandersman, A. An introduction to citizen participation, voluntary organizations, and community development: Insights for empowerment through research. Am J. community Psychol. 1990, 18, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, F. Social Constructivism and Action Research: Transforming teaching and learning though collaborative practice. In Action Research for Inclusive Education: Participation and Democracy in Teaching and Learning; Armstrong, F., Tsokova, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.S. Doing social constructivist research means making empathic and aesthetic connections with participants. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2014, 22, 538–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.D. Customer Orientation and Market Action; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Witell, L.; Kristensson, P.O.; Gustafsson, A.; Löfgren, M. Idea generation: Customer co-creation versus traditional market research techniques. J. Serv. Manag. 2011, 22, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aiken, G.T.; Du Luxembourg, U. Social Innovation and Participatory Action Research: A way to research community? Eur. Public Soc. Innov. Rev. 2017, 2, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Díez, J.; Conde, P.; Sandin, M.; Urtasun, M.; López, R.; Carrero, J.L.; Franco, M. Understanding the local food envi-ronment: A participatory photovoice project in a low-income area in Madrid, Spain. Health Place 2017, 43, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.C.; Hilchey, K.G. A review of citizen science and community-based environmental monitoring: Issues and opportunities. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2010, 176, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kujala, S. User involvement: A review of the benefits and challenges. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2003, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloane, D.C.; the REACH Coalition of the African American Building a Legacy of Health Project; Diamant, A.L.; Lewis, L.B.; Yancey, A.K.; Flynn, G.; Nascimento, L.M.; McCarthy, W.J.; Guinyard, J.J.; Cousineau, M.R. Improving the nutritional resource environment for healthy living through community-based participatory research. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2003, 18, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Coughlin, S.S.; Smith, S.A. Community-based participatory research to promote healthy diet and nutrition and pre-vent and control obesity among African-Americans: A literature review. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2017, 4, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rahl, G.M. Risk Reduction Through Public Participation in Environmental Decisions. Nav. Eng. J. 1996, 108, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Frewer, L.J. Public Participation Methods: A Framework for Evaluation. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2000, 25, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, A.; Jewkes, R. What is participatory research? Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindon, S.; Pain, R.; Kesby, M. (Eds.) Participatory Action Research Approaches and Methods: Connecting People, Participation and Place; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, J.L.; Zuckerberg, B.; Bonter, D.N. Citizen Science as an Ecological Research Tool: Challenges and Benefits. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2010, 41, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McNiff, J.; Whitehead, J. All You Need to Know About Action Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-opting customer competence. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2000, 78, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sijtsema, S.J.; Fogliano, V.; Hageman, M. Tool to support citizen participation and multidisciplinarity in food innova-tion: Circular Food Design. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amilien, V.; Tocco, B.; Strandbakken, P. At the heart of controversies: Hybrid forums as an experimental multi-actor tool to enhance sustainable practices in localized agro-food systems. Br. Food J. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Puttelaar, J.; Verain, M.C.; Onwezen, M.C. The potential of enriching food consumption data by use of con-sumer generated data: A case from RICHFIELDS. In Proceedings of the Measuring Behaviour, Dublin, Ireland, 25–27 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, C.A.; Carbone, E.T. “Just Say It Like It Is!” Use of a Community-Based Participatory Approach to Develop a Technology-Driven Food Literacy Program for Adolescents. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 2017, 38, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitz, R.; Queiroz, F.; Pereira, C.; Leite, L.C.; Ferranti, M.P.; Dam, P. Do You Eat This? Changing Behaviour Through Gamification, Crowdsourcing and Civic Engagement. In International Conference of Design, User Experience, and Usability; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Nov, O.; Arazy, O.; Anderson, D. Scientists@ Home: What drives the quantity and quality of online citizen science participation? PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dickel, S.; Franzen, M. The “Problem of Extension” revisited: New modes of digital participation in science. J. Sci. Commun. 2016, 15, A06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment. Health Educ. Behav. 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Belon, A.P.; Nieuwendyk, L.M.; Vallianatos, H.; Nykiforuk, C.I. Perceived community environmental influences on eating behaviors: A Photovoice analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 171, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenwood, D.J.; Levin, M. Introduction to Action Research: Social Research for Social Change; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Swords, A. Action research on organizational change with the Food Bank of the Southern Tier: A regional food bank’s efforts to move beyond charity. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 36, 849–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, M.; Ammerman, A.; Eng, E.; Garlehner, G.; Lohr, K.N.; Griffith, D.; Webb, L. Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence: Summary. In AHRQ Evidence Report Summaries; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, S.M.; Kay, J.S.; Lin, G.C. Nourishing a partnership to improve middle school lunch options: A community-based participatory research project. Fam. Community Health 2015, 38, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C. Including context in consumer segmentation: A literature overview shows the what, why, and how. Methods Consum. Res. 2018, 1, 383–400. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson, E. The power of self-persuasion. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bem, D.J. Self-Perception Theory. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1972, 6, 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepitone, A.; Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Am. J. Psychol. 1959, 72, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wildschut, D. The need for citizen science in the transition to a sustainable peer-to-peer-society. Futures 2017, 91, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menozzi, D.; Kostov, K.; Sogari, G.; Arpaia, S.; Moyankova, D.; Mora, C. A stakeholder engagement approach for identi-fying future research directions in the evaluation of current and emerging applications of GMOs. Biobased Appl. Econ. 2017, 6, 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, B.K.; Jones, R.E. Citizen Participation in Natural Resource Management: Does Representativeness Matter? Sociol. Spectr. 2005, 25, 715–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braver, S.L.; Bay, R.C. Assessing and compensating for self-selection bias (non-representativeness) of the family re-search sample. J. Marriage Fam. 1992, 54, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Mortel, T.F. Faking it: Social desirability response bias in self-report research. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 25, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, S.; Stratton, R. An integrated regional approach to risk management of industrial systems. Nucl. Saf. 1993, 34, 7108106. [Google Scholar]

- Franzoni, C.; Sauermann, H. Crowd science: The organization of scientific research in open collaborative projects. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blackstock, K.; Kelly, G.; Horsey, B. Developing and applying a framework to evaluate participatory research for sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 60, 726–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Taylor, S.A. The Effectiveness of Customer Participation in New Product Development: A Meta-Analysis. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Farioli, F.; Fukushi, K.; Yarime, M. Sustainability science: Bridging the gap between science and society. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandstetter, S.; Rüter, J.; Curbach, J.; Loss, J. A systematic review on empowerment for healthy nutrition in health promotion. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 3146–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. The four service marketing myths: Remnants of a goods-based, manufacturing model. J. Serv. Res. 2004, 6, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- May, J. Ladders, Stars and Triangles: Old and New Theory for the Practice of Public Participation. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 48, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Van den Puttelaar, J.; Verain, M.C.D.; Veldkamp, T. Consumer acceptance of insects as food and feed: The relevance of affective factors. Food Qual. Pref. 2019, 77, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Selected Forms of Participatory Research | Definition | Main Methods Used in Food Behaviour Research | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citizen science | A process in which citizens (i.e., amateurs or non-professionals) are actively involved in science as data collectors, often as volunteers | - Smartphone application - (Online) survey | The “food profiler” is a smartphone application in which citizens can track what they eat [24]. It provides a platform through which citizens can track their own consumption patterns, thereby contributing to research. |

| Crowd science | Collaborative contributions of a large group of people to the different steps of the research process. | - Internet - Online communication - Self-trackers - Crowd sourcing (e.g., all means to receive valuable input on research tasks, leaving space for creative input) | The Quantified Self movement (http://quantifiedself.com), which motivates citizens to participate in science by tracking themselves, asking questions and sharing knowledge. |

| Photovoice | A process by which people can identify, represent, and enhance their community through a specific photographic technique | - Taking photos - Focus groups (discussing the photos) - Interviews (sharing stories with photos) | Diez and colleagues [10] conducted a photovoice project with adult residents of a low-income urban area to understand the characteristics of the local food environment influencing residents’ diets. The method involved citizens taking pictures of all the features related to the food environment in the neighborhood. |

| Community-based participatory research | A method in which researchers co-conduct research with citizens from a community and in which community members are involved in the entire research process. | - Advisory boards (e.g., defining the problem, designing the methods to collect data, collecting and analysing the data, and presenting the findings) | Wickham and Carbone [25] formed an advisory group (Kid Council) to direct the design of a food literacy program and to implement a pilot version of the program to assess participants’ attitudes to participate. Adolescents from the community sat in an advisory group and provided feedback on the program’s design and development. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Onwezen, M.C.; Bouwman, E.P.; van Trijp, H.C.M. Participatory Methods in Food Behaviour Research: A Framework Showing Advantages and Disadvantages of Various Methods. Foods 2021, 10, 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10020470

Onwezen MC, Bouwman EP, van Trijp HCM. Participatory Methods in Food Behaviour Research: A Framework Showing Advantages and Disadvantages of Various Methods. Foods. 2021; 10(2):470. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10020470

Chicago/Turabian StyleOnwezen, Marleen C., Emily P. Bouwman, and Hans C. M. van Trijp. 2021. "Participatory Methods in Food Behaviour Research: A Framework Showing Advantages and Disadvantages of Various Methods" Foods 10, no. 2: 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10020470

APA StyleOnwezen, M. C., Bouwman, E. P., & van Trijp, H. C. M. (2021). Participatory Methods in Food Behaviour Research: A Framework Showing Advantages and Disadvantages of Various Methods. Foods, 10(2), 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10020470