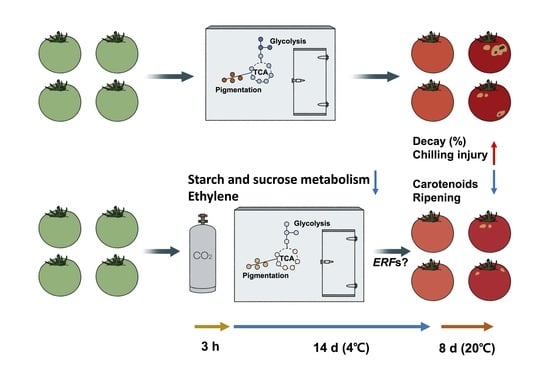

Carbon Dioxide Pretreatment and Cold Storage Synergistically Delay Tomato Ripening through Transcriptional Change in Ethylene-Related Genes and Respiration-Related Metabolism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

2.2. Gas Chromatography Analysis

2.3. Fruit Quality Evaluation

2.4. Carotenoid Analysis

2.5. Transcriptome Analysis

2.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.7. Water-Soluble Primary Metabolite Profiling Using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Respiration and Ethylene Production

3.2. Effect of CO2 on Fruit Quality and Ripening of Tomatoes

3.3. Effect of CO2 on Chilling Injury and Decay of Tomatoes

3.4. RNA-Seq and Functional Categorization of CO2-Responsive Genes

3.5. Primary Metabolite Profiling for Pathway Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Role of CO2 Treatment in the Response of Tomato Fruit to Low Temperature

4.2. CO2-Induced Global Transcriptional Changes

4.3. Effect of CO2 Treatment on Tomato Metabolites and Quality

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cruz-Mendívil, A.; Lopez-Valenzuela, J.A.; Calderón-Vázquez, C.L.; Vega-García, M.O.; Reyes-Moreno, C.; Valdez-Ortiz, A. Transcriptional changes associated with chilling tolerance and susceptibility in ‘Micro-Tom’ tomato fruit using RNA-Seq. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2015, 99, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltveit, E.M.; Morris, L.L. Overview on Chilling Injury of Horticultural Crops. Chill. Inj. Hortic. Crop. 1990, 1, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- García, V.O.M.; López-Espinoza, G.; Ontiveros, J.C.; Caro-Corrales, J.J.; Vargas, F.D.; López-Valenzuela, J.A. Changes in Protein Expression Associated with Chilling Injury in Tomato Fruit. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2010, 135, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauxmann, A.M.; Brun, B.; Borsani, J.; Bustamante, C.A.; Budde, C.O.; Lara, M.V.; Drincovich, M.F. Transcriptomic Profiling During the Post-Harvest of Heat-Treated Dixiland Prunus Persica Fruits: Common and Distinct Response to Heat and Cold. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnal, L.; del Río, M.A. Removing Astringency by Carbon Dioxide and Nitrogen-Enriched Atmospheres in Per-simmon Fruit Cv. “Rojo Brillante”. J. Food Sci. 2003, 68, 1516–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanch, M.; Rosales, R.; Mateos, R.; Perez-Gago, M.B.; Sanchez-Ballesta, M.T.; Escribano, M.I.; Merodio, C.; Sanchez-Ballesta, M.T. Effects of High CO2 Levels on Fermentation, Peroxidation, and Cellular Water Stress inFragaria vescaStored at Low Temperature in Conditions of Unlimited O. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Shi, J.; Jiang, C.-Z.; Feng, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Q. A short-term carbon dioxide treatment inhibits the browning of fresh-cut burdock. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2015, 110, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.; Watkins, C.B. Firmness and Aroma Composition of Strawberries following Short-term High Carbon Dioxide Treatments. Hortic. Sci. 1995, 30, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.G.; Sanz, C. Effect of high-oxygen and high-carbon-dioxide atmospheres on strawberry flavor and other quality traits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 2370–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, J.; Lim, S.; Yi, G.; Lee, J.G.; Lee, E.J. Integrated transcriptomic-metabolomic analysis reveals cellular responses of harvested strawberry fruit subjected to short-term exposure to high levels of carbon dioxide. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 148, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, T.; Yin, X.-R.; Shi, Y.-N.; Luo, Z.-R.; Yao, Y.-C.; Grierson, D.; Ferguson, I.B.; Chen, K.-S. Ethylene-responsive transcription factors interact with promoters of ADH and PDC involved in persimmon (Diospyros kaki) fruit de-astringency. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 6393–6405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, E.-H.; Lee, J.-S.; Kim, J.-G. Cell wall degrading enzymes activity is altered by high carbon dioxide treatment in postharvest ‘Mihong’ peach fruit. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 225, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangwanangkul, P.; Bae, Y.-S.; Lee, J.-S.; Choi, H.-J.; Choi, J.-W.; Park, M.-H. Short-term pretreatment with high CO2 alters organic acids and improves cherry tomato quality during storage. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2017, 58, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezz, M.T.; Ritenour, M.A.; Brecht, J.K. Hot Water and Elevated Co2 Effects on Proline and Other Compositional Changes in Relation to Postharvest Chilling Injury Ofmarsh’grapefruit. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2004, 129, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, P.; Lanza, G.; Tonini, G. Effects of pre-storage carbon dioxide treatments and storage temperatures on membranosis of ‘Femminello comune’ lemons. Sci. Hortic. 1991, 46, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, M.; Pretel, M.T.; Martínez-Madrid, M.C.; Romojaro, F.; Riquelme, F. CO2Treatment of Zucchini Squash Reduces Chilling-Induced Physiological Changes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 2465–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, R.; Romero, I.; Fernandez-Caballero, C.; Escribano, M.I.; Merodio, C.; Sanchez-Ballesta, M.T. Low Temperature and Short-Term High-CO2 Treatment in Postharvest Storage of Table Grapes at Two Maturity Stages: Effects on Transcriptome Profiling. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.L.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, L.; Huang, W.; Wang, R.D. Effect of Ultrasonic and Ball-Milling Treatment on Cell Wall, Nutrients, and Antioxidant Capacity of Rose (Rosa Rugosa) Bee Pollen, and Identification of Bioactive Com-ponents. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 5350–5357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.-F.; Gong, Z.-H.; Wu, M.-B.; Chan, H.; Yuan, Y.-J.; Tang, N.; Zhang, Q.; Miao, M.-J.; Chang, W.; Li, Z.; et al. Integrative comparative analyses of metabolite and transcript profiles uncovers complex regulatory network in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) fruit undergoing chilling injury. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albornoz, K.; Cantwell, M.I.; Zhang, L.; Beckles, D.M. Integrative analysis of postharvest chilling injury in cherry tomato fruit reveals contrapuntal spatio-temporal responses to ripening and cold stress. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.-H.; Sangwanangkul, P.; Choi, J.-W. Reduced chilling injury and delayed fruit ripening in tomatoes with modified atmosphere and humidity packaging. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 231, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, G.; Davis, J.; Dezman, D. Rapid Extraction of Lycopene and Β-Carotene from Reconstituted Tomato Paste and Pink Grapefruit Homogenates. J. Food Sci. 1990, 55, 1460–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, A.; Zamani, Z.; Mousavi, A.; Fatahi, R.; Alavijeh, M.K.; Dehsara, B.; Salami, S.A. An Effective Protocol for Isolation of High-Quality Rna from Pomegranate Seeds. Asian Aust. J. Plant Sci. Biotechnol. 2012, 6, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Pertea, M.; Kim, D.; Pertea, G.M.; Leek, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1650–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caraux, G.; Pinloche, S. PermutMatrix: A graphical environment to arrange gene expression profiles in optimal linear order. Bioinformatics 2004, 21, 1280–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisec, J.; Schauer, N.; Kopka, J.; Willmitzer, L.; Fernie, A.R. Gas Chromatography Mass Spec-trometry–Based Metabolite Profiling in Plants. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Ku, K.M.; Choi, S.; Cardarelli, M. Vegetal-Derived Biostimulant Enhances Ad-ventitious Rooting in Cuttings of Basil, Tomato, and Chrysanthemum Via Brassinosteroid-Mediated Processes. Agronomy 2019, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, E.S.; Stushnoff, C.; Sampson, D.A. Relationship of Fruit Color and Light Exposure to Lycopene Content and Anti-oxidant Properties of Tomato. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2003, 83, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suslow, V.T.; Cantwell, M. Tomato: Recommendations for Maintaining Postharvest Quality. In Produce Facts; Kader, A.A., Ed.; Postharvest Technology Research & Information Center: Davis, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rothan, C.; Duret, S.; Chevalier, C.; Raymond, P. Suppression of Ripening-Associated Gene Expression in Tomato Fruits Subjected to a High CO2 Concentration. Plant Physiol. 1997, 114, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugkong, A.; McQuinn, R.; Giovannoni, J.J.; Rose, J.K.; Watkins, C.B. Expression of ripening-related genes in cold-stored tomato fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2011, 61, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.H.; Kim, J.G.; Ahn, S.E.; Lee, A.Y.; Bae, T.M.; Kim, D.R.; Hwang, Y.S. Potential Role of Pectate Lyase and Ca2+in the Increase in Strawberry Fruit Firmness Induced by Short-Term Treatment with High-Pressure CO. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, S685–S692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.S.; Min, J.H.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, J.G.; Huber, D.J. Potential mechanisms associated with strawberry fruit firmness increases mediated by elevated pCO. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2012, 53, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Chaudhuri, S.; Yang, L.; Du, L.; Poovaiah, B.W. A Calcium/Calmodulin-regulated Member of the Receptor-like Kinase Family Confers Cold Tolerance in Plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 7119–7126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.-R.; Allan, A.C.; Xu, Q.; Burdon, J.; Dejnoprat, S.; Chen, K.; Ferguson, I.B. Differential Expression of Kiwifruit Erf Genes in Response to Postharvest Abiotic Stress. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2012, 66, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Pirrello, J.; Kesari, R.; Mila, I.; Roustan, J.; Li, Z.; Latché, A.; Pech, J.; Bouzayen, M.; Regad, F. A Dominant Repressor Version of the Tomato S L-Erf. B 3 Gene Confers Ethylene Hypersensitivity Via Feedback Regulation of Ethylene Signaling and Response Components. Plant J. 2013, 76, 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, R. Enhanced Tolerance to Freezing in Tobacco and Tomato Overexpressing Tran-scription Factor Terf2/Leerf2 Is Modulated by Ethylene Biosynthesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2010, 73, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Gomes, B.L.; Mila, I.; Purgatto, E.; Peres, L.E.; Frasse, P.; Maza, E.; Zouine, M.; Roustan, J.-P.; Bouzayen, M.; et al. Comprehensive Profiling of Ethylene Response Factor Expression Identifies Ripening-Associated ERF Genes and Their Link to Key Regulators of Fruit Ripening in Tomato. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 1732–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Hu, Z.; Grierson, D. Differential regulation of tomato ethylene responsive factor LeERF3b, a putative repressor, and the activator Pti4 in ripening mutants and in response to environmental stresses. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.K.; Kumar, R.; Solanke, A.U.; Sharma, R.; Tyagi, A.K.; Sharma, A.K. Identification, phylogeny, and transcript profiling of ERF family genes during development and abiotic stress treatments in tomato. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2010, 284, 455–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, I.; Vazquez-Hernandez, M.; Escribano, M.I.; Merodio, C.; Sanchez-Ballesta, M.T. Expression Profiles and DNA-Binding Affinity of Five Erf Genes in Bunches of Vitis Vinifera Cv. Cardinal Treated with High Levels of CO2 at Low Temperature. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.-Y.; Park, M.-H.; Choi, J.-W.; Kim, J.-G. Gene network underlying the response of harvested pepper to chilling stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2017, 219, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, C.S.; Llop-Tous, M.I.; Grierson, D. The Regulation of 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylic Acid Synthase Gene Expression during the Transition from System-1 to System-2 Ethylene Synthesis in Tomato. Plant Physiol. 2000, 123, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klann, E.M.; Chetelat, R.T.; Bennett, A.B. Expression of Acid Invertase Gene Controls Sugar Composition in Tomato (Lycopersicon) Fruit. Plant Physiol. 1993, 103, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centeno, D.C.; Osorio, S.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Bertolo, A.L.; Carneiro, R.T.; Araújo, W.L.; Steinhauser, M.-C.; Michalska, J.; Rohrmann, J.; Geigenberger, P.; et al. Malate Plays a Crucial Role in Starch Metabolism, Ripening, and Soluble Solid Content of Tomato Fruit and Affects Postharvest Softening. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 162–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Sun, P.; Lu, M.; Hu, J. Physiological and metabolic responses of Salix sinopurpurea and Salix suchowensis to drought stress. Trees 2019, 34, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barickman, T.C.; Ku, K.-M.; Sams, C.E. Differing precision irrigation thresholds for kale (Brassica oleracea L. var. acephala) induces changes in physiological performance, metabolites, and yield. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 180, 104253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.R.; Lee, J.G. Ripening-Dependent Changes in Antioxidants, Color Attributes, and Antioxidant Activity of Seven Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Cultivars. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2016, 2016, 5498618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | 0 d | 7 d | 14 d | 14 + 8 d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firmness (N) | ||||

| Control | 19.83 ± 0.41 Aa 1 | 16.56 ± 0.18 Ab | 13.67 ± 0.34 Ac | 6.54 ± 0.38 Bd |

| 30% CO2 | 19.94 ± 0.47 Aa | 15.88 ± 1.23 Ab | 13.53 ± 0.28 Ac | 8.07 ± 0.50 Ad |

| 60% CO2 | 20.42 ± 0.67 Aa | 17.84 ± 0.70 Ab | 13.19 ± 0.57 Ac | 7.94 ± 0.51 Ad |

| SSC (%) | ||||

| Control | 4.28 ± 0.08 Aa | 4.46 ± 0.04 Aa | 4.48 ± 0.02 Aa | 4.48 ± 0.07 Aa |

| 30% CO2 | 4.42 ± 0.10 Aa | 4.44 ± 0.07 Aa | 4.46 ± 0.07 Aa | 4.50 ± 0.06 Aa |

| 60% CO2 | 4.26 ± 0.07 Ab | 4.50 ± 0.03 Aa | 4.38 ± 0.04 Aab | 4.40 ± 0.04 Aa |

| TA (%) | ||||

| Control | 1.07 ± 0.01 Aa | 1.05 ± 0.02 Aa | 0.79 ± 0.05 Ab | 0.66 ± 0.01 Ac |

| 30% CO2 | 0.94 ± 0.02 Aa | 0.99 ± 0.02 ABa | 0.85 ± 0.03 Ab | 0.68 ± 0.01 Ac |

| 60% CO2 | 1.08 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.98 ± 0.02 Ab | 0.83 ± 0.02 Ac | 0.65 ± 0.02 Ad |

| pH | ||||

| Control | 3.99 ± 0.02 Ab | 3.97 ± 0.01 Bb | 3.95 ± 0.03 Ab | 4.32 ± 0.04 Aa |

| 30% CO2 | 3.99 ± 0.02 Ac | 4.01 ± 0.02 ABbc | 4.07 ± 0.04 Ab | 4.34 ± 0.02 Aa |

| 60% CO2 | 3.93 ± 0.02 Ac | 4.05 ± 0.02 Ab | 4.05 ± 0.04 Ab | 4.40 ± 0.02 Aa |

| Treatment | 0 d | 7 d | 14 d | 14 + 8 d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lutein (mg kg−1) | ||||

| Control | 27.84 ± 4.16 Aa 1 | 24.45 ± 2.95 Ba | 10.94 ± 1.32 Ab | 8.85 ± 0.36 Ab |

| 30% CO2 | 32.45 ± 1.95 Aa | 34.94 ± 4.55 ABa | 11.88 ± 2.06 Ab | 8.55 ± 0.32 Ab |

| 60% CO2 | 33.80 ± 1.85 Aa | 36.25 ± 0.01 Aa | 11.60 ± 0.63 Ab | 8.61 ± 0.64 Ab |

| Lycopene (mg kg−1) | ||||

| Control | 5.05 ± 0.43 Ab | 4.82 ± 0.69 Ab | 10.64 ± 1.79 Ab | 39.56 ± 3.87 Aa |

| 30% CO2 | 6.64 ± 1.54 Ab | 4.74 ± 0.72 Ab | 6.45 ± 1.48 ABb | 26.88 ± 0.73 Ba |

| 60% CO2 | 6.21 ± 0.12 Ab | 3.37 ± 0.44 Ab | 4.72 ± 0.18 Bb | 26.57 ± 2.21 Ba |

| Beta-Carotene (mg kg−1) | ||||

| Control | 15.06 ± 2.84 Aa | 9.64 ± 1.88 Bab | 7.38 ± 0.80 Ab | 10.24 ± 0.18 Aab |

| 30% CO2 | 14.67 ± 0.79 Aab | 15.92 ± 2.28 Aa | 9.73 ± 2.54 Abc | 8.36 ± 0.29 Ac |

| 60% CO2 | 17.02 ± 2.30 Aa | 16.26 ± 0.64 Aa | 7.51 ± 0.97 Ab | 9.33 ± 0.91 Ab |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, M.-H.; Kim, S.-J.; Lee, J.-S.; Hong, Y.-P.; Chae, S.-H.; Ku, K.-M. Carbon Dioxide Pretreatment and Cold Storage Synergistically Delay Tomato Ripening through Transcriptional Change in Ethylene-Related Genes and Respiration-Related Metabolism. Foods 2021, 10, 744. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040744

Park M-H, Kim S-J, Lee J-S, Hong Y-P, Chae S-H, Ku K-M. Carbon Dioxide Pretreatment and Cold Storage Synergistically Delay Tomato Ripening through Transcriptional Change in Ethylene-Related Genes and Respiration-Related Metabolism. Foods. 2021; 10(4):744. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040744

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Me-Hea, Sun-Ju Kim, Jung-Soo Lee, Yoon-Pyo Hong, Seung-Hun Chae, and Kang-Mo Ku. 2021. "Carbon Dioxide Pretreatment and Cold Storage Synergistically Delay Tomato Ripening through Transcriptional Change in Ethylene-Related Genes and Respiration-Related Metabolism" Foods 10, no. 4: 744. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040744

APA StylePark, M.-H., Kim, S.-J., Lee, J.-S., Hong, Y.-P., Chae, S.-H., & Ku, K.-M. (2021). Carbon Dioxide Pretreatment and Cold Storage Synergistically Delay Tomato Ripening through Transcriptional Change in Ethylene-Related Genes and Respiration-Related Metabolism. Foods, 10(4), 744. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040744