Recent Applications of Mixture Designs in Beverages, Foods, and Pharmaceutical Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Focus Questions

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.4. Data Analysis

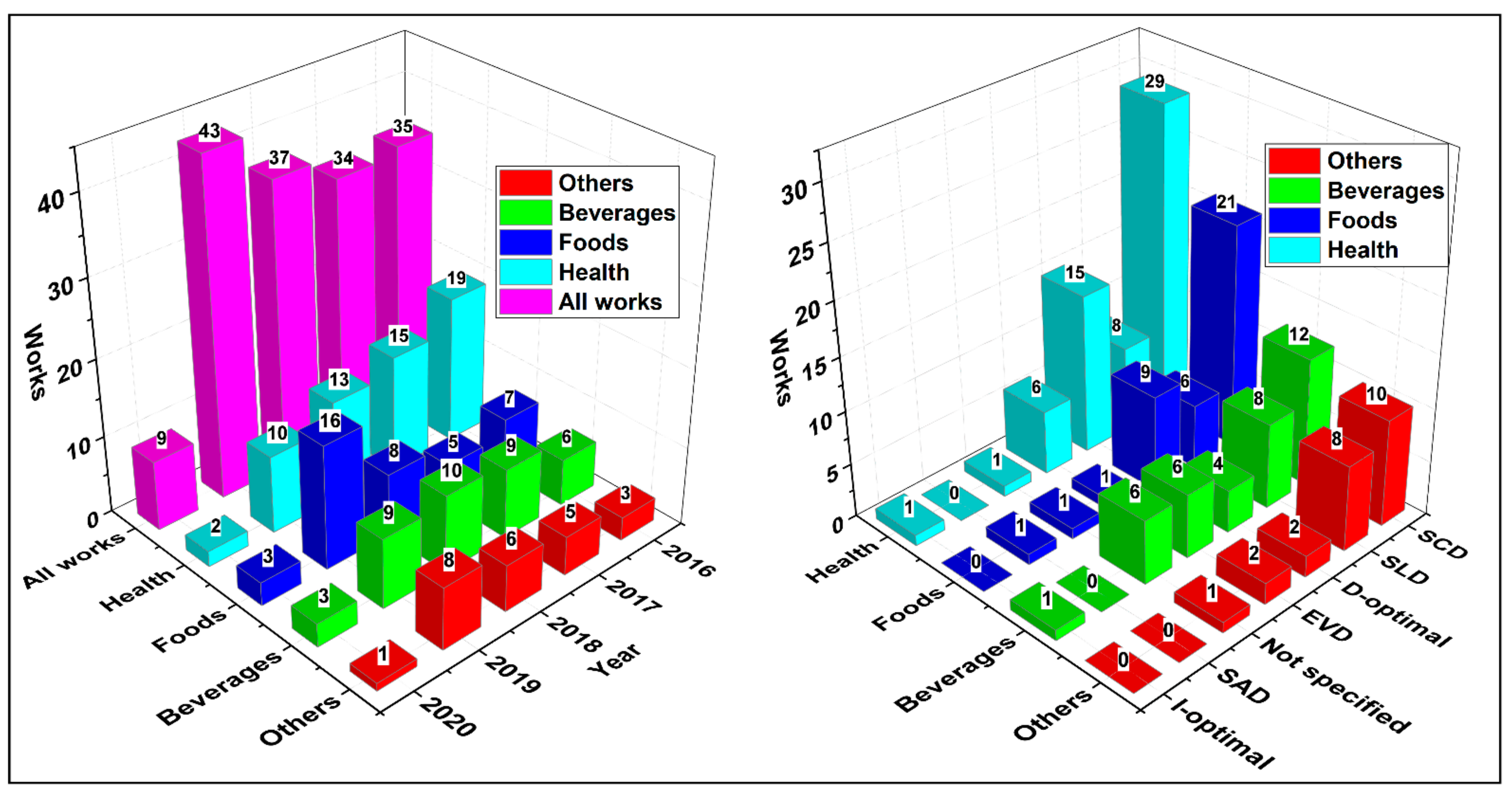

3. Mixture Designs Applications

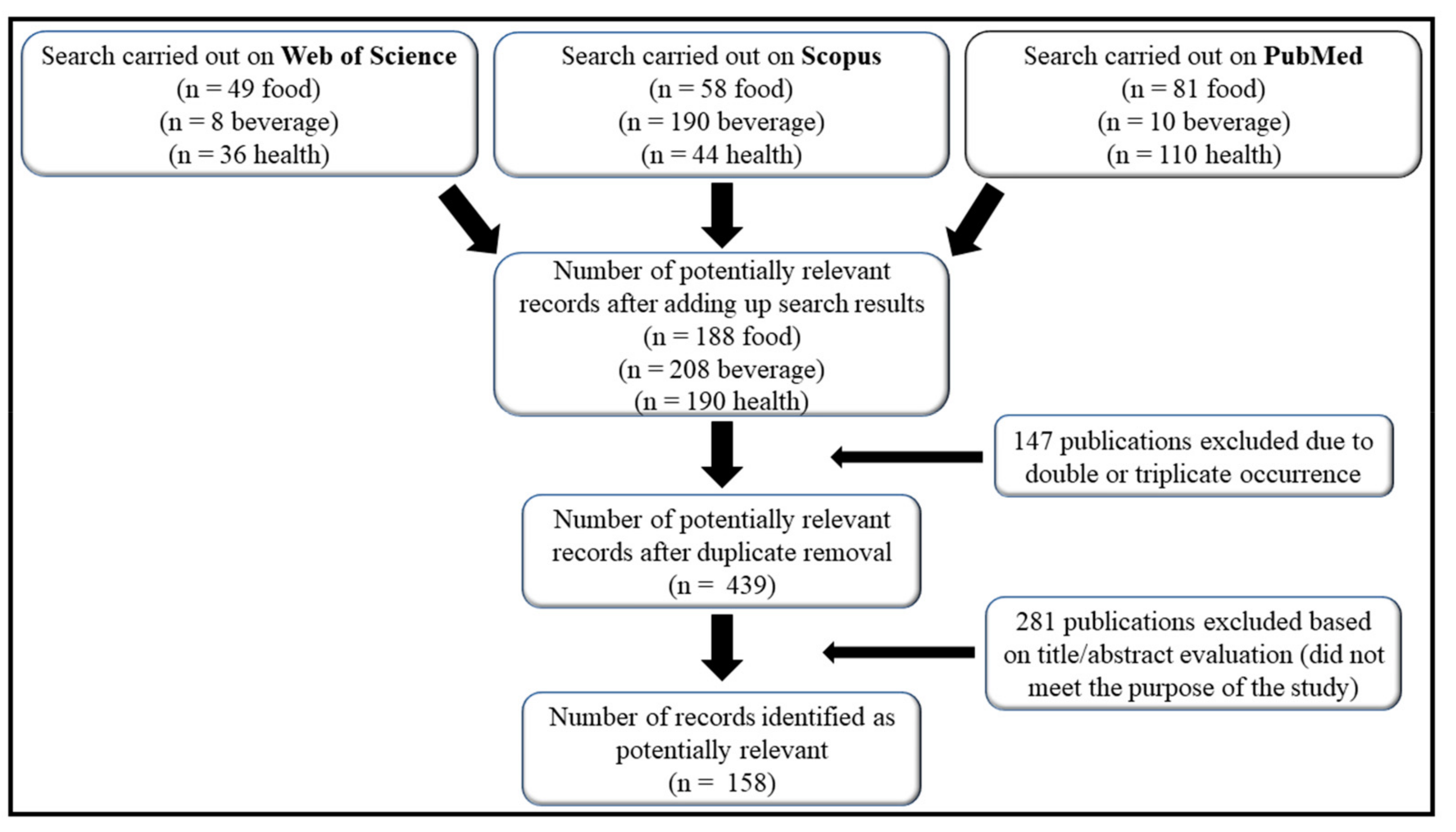

3.1. Literature Search

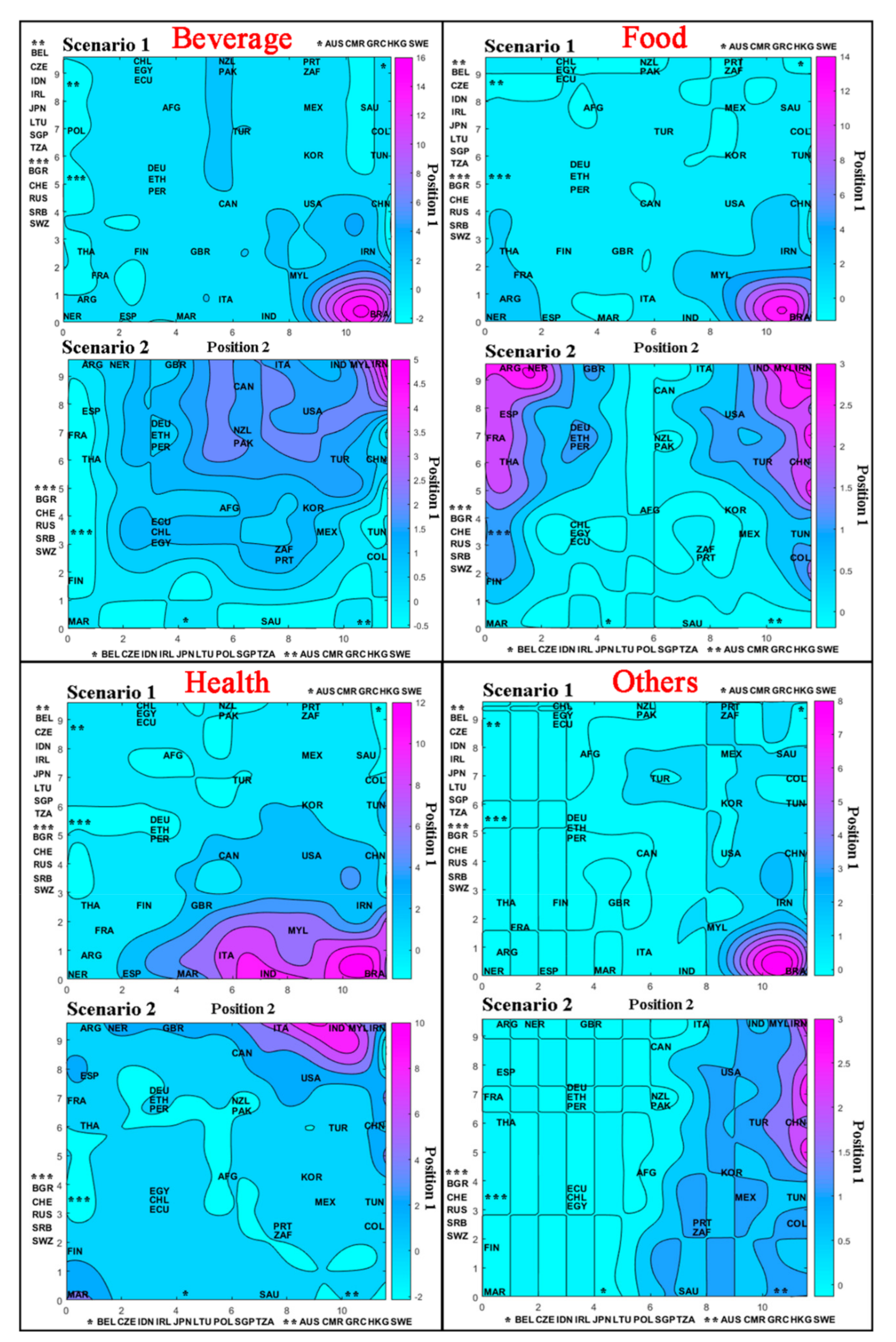

3.2. Application of Mixture Design around the World

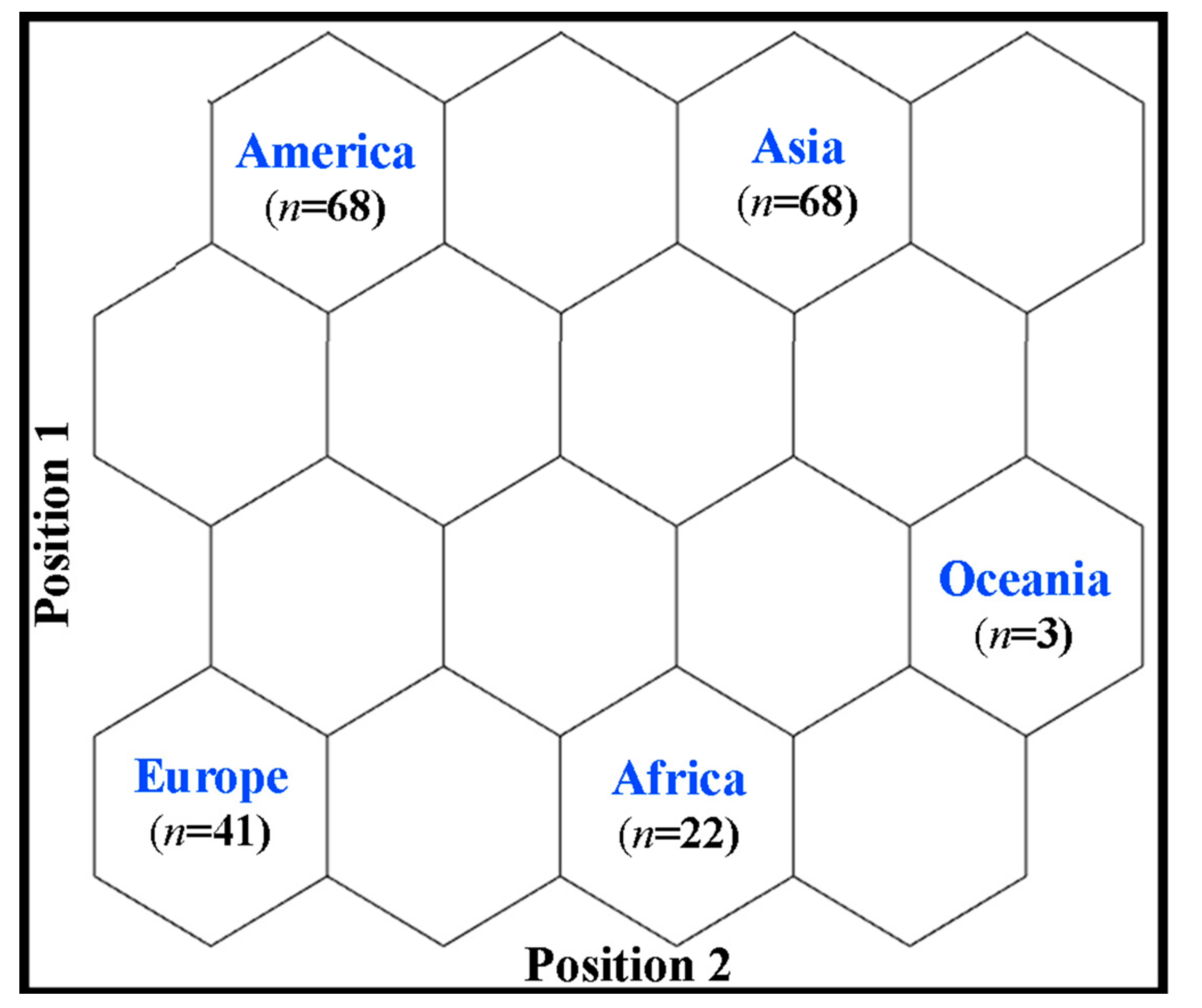

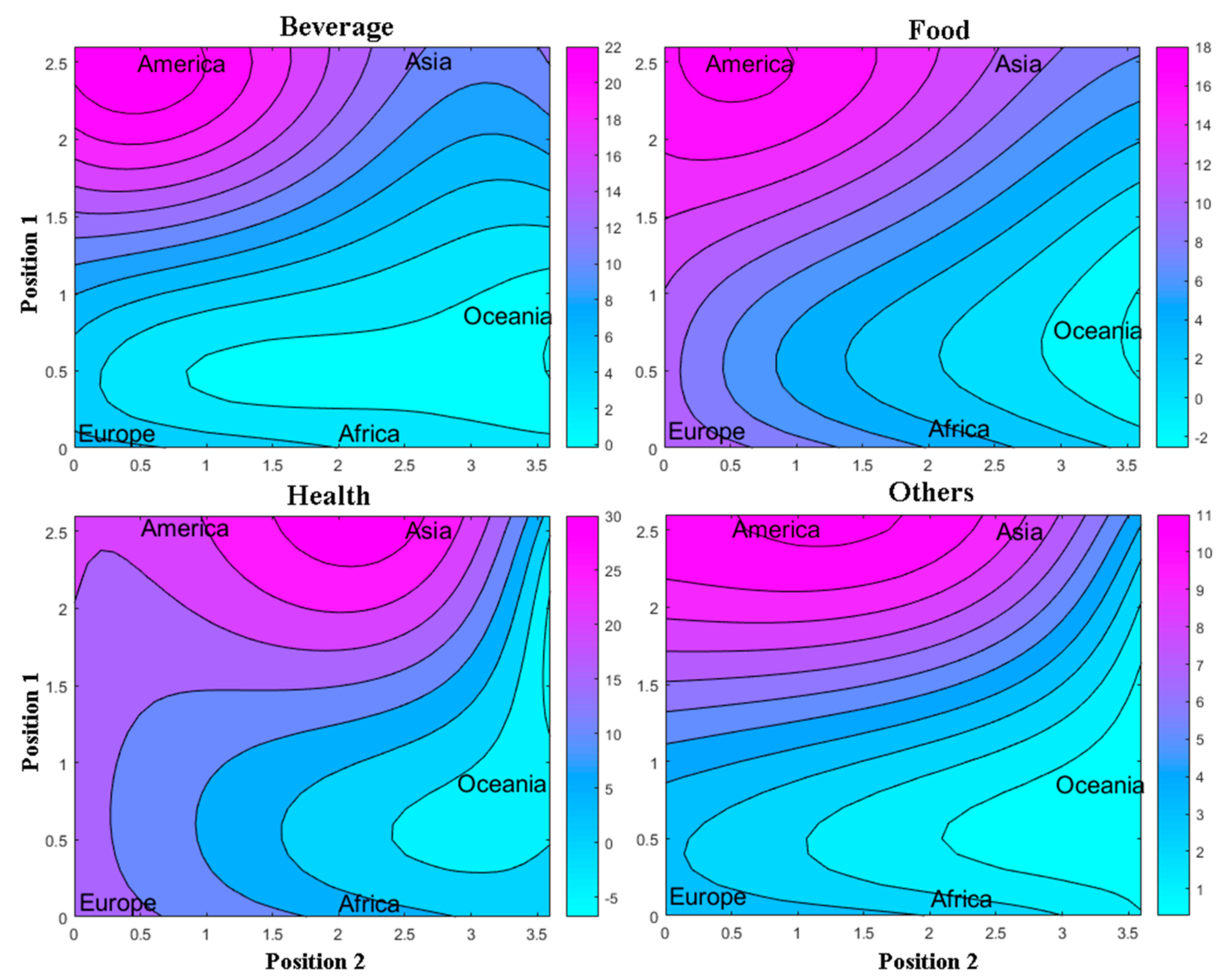

3.3. Application of Mixture Design by Continent

3.4. Application of Mixture Design by Area

3.5. Application of Mixture Design in Beverage

3.6. Application of Mixture Design in Food

3.7. Application of Mixture Design in Pharmaceutical Health

3.8. Application of Mixture Design in Other Areas

3.9. Behaviors, Trends, and Perspectives of Mixture Design Applications

3.10. Statistical Packages Used for Mixture Design Applications

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guizellini, F.C.; Marcheafave, G.G.; Rakocevic, M.; Bruns, R.E.; Scarminio, I.S.; Soares, P.K. PARAFAC HPLC-DAD metabolomic fingerprint investigation of reference and crossed coffees. Food Res. Int. 2018, 113, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros Neto, B.; Scarminio, I.S.; Bruns, R.E. Como Fazer Experimentos: Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento na Ciência e na Indústria, 4th ed.; Bookman: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2010; ISBN 8577807134. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, S.L.C. Introdução às Técnicas de Planejamento de Experimentos, 1st ed.; Vento Leste: Salvador, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Galvan, D.; Aquino, A.; Effting, L.; Mantovani, A.C.G.; Bona, E.; Conte-Junior, C.A. E-sensing and nanoscale-sensing devices associated with data processing algorithms applied to food quality control: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orives, J.R.; Galvan, D.; Coppo, R.L.; Rodrigues, C.H.F.; Angilelli, K.G.; Borsato, D. Multiresponse optimisation on biodiesel obtained through a ternary mixture of vegetable oil and animal fat: Simplex-centroid mixture design application. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 79, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orives, J.R.; Galvan, D.; Pereira, J.L.; Coppo, R.L.; Borsato, D. Experimental design applied for cost and efficiency of antioxidants in biodiesel. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2014, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Hurkat, P.; Jain, S.K. Development of liposomes using formulation by design: Basics to recent advances. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2019, 224, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado, V.; Montgomery, D.C. Planejamento de Experimentos Usando o Statistica; Editora E-Papers: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2003; ISBN 8587922831. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments, 6th ed.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Galvan, D.; Orives, J.R.; Coppo, R.L.; Rodrigues, C.H.F.; Spacino, K.R.; Pinto, J.P.; Borsato, D.D. Study of oxidation kinetics of B100 biodiesel from soybean and pig fat: Activation energy determination. Quim. Nova 2014, 37, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffé, H. Experiments with Mixtures. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1958, 20, 344–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, T.; Lewicki, P. Statistics: Methods and Applications: A Comprehensive Reference for Science, Industry, and Data Mining, 1st ed.; StatSoft, Inc.: Tusla, OK, USA, 2006; ISBN 1884233597. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell, J.A. Experiments with Mixtures: Designs, Models and the Analysis of Mixture Data, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 9780471393672. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffé, H. The Simplex-Centroid design for experiments with mixtures. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1963, 25, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, J.A. Some comments on designs for cox’s mixture polynomial. Technometrics 1975, 17, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, R.A.; Anderson, V.L. Extreme vertices design of mixture experiments. Technometrics 1966, 8, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepel, G.F. Defining consistent constraint regions in mixture experiments. Technometrics 1983, 25, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, R.H.; Montgomery, D.C.; Anderson-Cook, C.M. Response Surface Methodology: Process and Product Optimization Using Designed Experiments, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0-471-58100-0. [Google Scholar]

- Coppo, R.L.; Pereira, J.L.; Silva, H.C.; Angilelli, K.G.; Rodrigues, P.R.P.; Galvan, D.; Borsato, D. Effect of natural antioxidants on oxidative stability of biodiesel from soybean oil. Applying simplex-centroid design. J. Biobased Mater. Bioenergy 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepel, G.F.; Szychowski, J.M.; Loeppky, J.L. Augmenting scheffé linear mixture models with squared and/or crossproduct terms. J. Qual. Technol. 2002, 34, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsato, D.; Galvan, D.; Pereira, J.L.; Orives, J.R.; Angilelli, K.G.; Coppo, R.L. Kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of biodiesel oxidation with synthetic antioxidants: Simplex centroid mixture design. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2014, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes Filho, R.C.; Galvan, D.; Effting, L.; Terhaag, M.M.; Yamashita, F.; de Toledo Benassi, M.; Spinosa, W.A. Effects of adding spices with antioxidants compounds in red ale style craft beer: A simplex-centroid mixture design approach. Food Chem. 2021, 365, 130478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.K.; Khanam, J.; Nanda, A. Optimization of preparation method for ketoprofen-loaded microspheres consisting polymeric blends using simplex lattice mixture design. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 69, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundele, O.M.A.; Awolu, O.O.; Badejo, A.A.; Nwachukwu, I.D.; Fagbemi, T.N. Development of functional beverages from blends of Hibiscus sabdariffa extract and selected fruit juices for optimal antioxidant properties. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 4, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastácio, A.; de Carvalho, I.S. Development of a beverage benchtop prototype based on sweet potato peels: Optimization of antioxidant activity by a mixture design. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 67, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo-Molina, D.A.; Arroyave-Maya, W.; González-Rodríguez, D.M.; Sepúlveda-Valencia, J.U.; Ciro-Velásquez, H.J. Design of a sodium-reduced preservative mixture for use in standard frankfurter sausages. DYNA 2019, 86, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonda, A.F.; Rinaldi, M.; Segale, L.; Palugan, L.; Cerea, M.; Vecchio, C.; Pattarino, F. Nanonized itraconazole powders for extemporary oral suspensions: Role of formulation components studied by a mixture design. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 83, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Nunes, R.; Gratieri, T.; Gelfuso, G.M.; Cunha-Filho, M. Mixture design applied in compatibility studies of catechin and lipid compounds. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 149, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, C.S.; Samaranayake, V.A.; Mohammadkhah, A.; Day, T.E.; Day, D.E. Iron phosphate glass waste forms for vitrifying Hanford AZ102 low activity waste (LAW), part I: Glass formation model. J. Non Cryst. Solids 2017, 458, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, P.; Zhang, B.; Lu, J.X.; Poon, C.S. A ternary optimization of alkali-activated cement mortars incorporating glass powder, slag and calcium aluminate cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 240, 117983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepel, G.F. 50 years of mixture experiment research: 1955–2004. In Response Surface Methodology and Related Topics; World Scientific: Singapore, 2006; pp. 283–327. [Google Scholar]

- Buruk Sahin, Y.; Aktar Demirtaş, E.; Burnak, N. Mixture design: A review of recent applications in the food industry. Pamukkale Univ. J. Eng. Sci. 2016, 22, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galvan, D.; Effting, L.; Torres Neto, L.; Conte-Junior, C.A. An overview of research of essential oils by self-organizing maps: A novel approach for meta-analysis study. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 3136–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohonen, T. Self-Organizing Maps; Springer Series in Information Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; Volume 30, ISBN 978-3-540-62017-4. [Google Scholar]

- Galvan, D.; Cremasco, H.; Carolina, A.; Mantovani, G.; Bona, E. Kinetic study of the transesterification reaction by artificial neural networks and parametric particle swarm optimization. Fuel 2020, 267, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haykin, S. Neural Networks: A Comprehensive Foundation; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-02-352761-6. [Google Scholar]

- Cremasco, H.; Borsato, D.; Angilelli, K.G.; Galão, O.F.; Bona, E.; Valle, M.E. Application of self-organising maps towards segmentation of soybean samples by determination of inorganic compounds content. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvan, D.; Effting, L.; Cremasco, H.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Can socioeconomic, health, and safety data explain the spread of covid-19 outbreak on Brazilian Federative Units? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvan, D.; Effting, L.; Cremasco, H.; Conte-Junior, C.A. The Spread of the COVID-19 Outbreak in Brazil: An overview by kohonen self-organizing map networks. Medicina 2021, 57, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra, M.A.; Santelli, R.E.; Oliveira, E.P.; Villar, L.S.; Escaleira, L.A. Response surface methodology (RSM) as a tool for optimization in analytical chemistry. Talanta 2008, 76, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, M.A.; Ferreira, S.L.C.; Novaes, C.G.; dos Santos, A.M.P.; Valasques, G.S.; da Mata Cerqueira, U.M.F.; dos Santos Alves, J.P. Simultaneous optimization of multiple responses and its application in Analytical Chemistry—A review. Talanta 2019, 194, 941–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafontaine, S.R.; Shellhammer, T.H. Sensory Directed mixture study of beers dry-hopped with cascade, centennial, and chinook. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2018, 76, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashaninejad, M.; Razavi, S.M.A. The effects of different gums and their interactions on the rheological properties of instant camel yogurt: A mixture design approach. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 13, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayouni Rad, A.; Pirouzian, H.R.; Toker, O.S.; Konar, N. Application of simplex lattice mixture design for optimization of sucrose-free milk chocolate produced in a ball mill. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 115, 108435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnopp, A.R.; Oliveira, K.G.; de Andrade, E.F.; Postingher, B.M.; Granato, D. Optimization of an organic yogurt based on sensorial, nutritional, and functional perspectives. Food Chem. 2017, 233, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.F.; Granato, D.; Barana, A.C. Development and optimization of a mixed beverage made of whey and water-soluble soybean extract flavored with chocolate using a simplex-centroid design. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 38, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghasempour, Z.; Moghaddas Kia, E.; Golbandi, S.; Ehsani, A. Effects of mixed starters on quality attributes of probiotic yogurt using statistical design approach. Nutr. Food Sci. 2019, 49, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Speranza, B.; Campaniello, D.; Sinigaglia, M.; Corbo, M.R.; Lamacchia, C. A preliminary report on the use of the design of experiments for the production of a synbiotic yogurt supplemented with gluten Friendly™ flour and bifidobacterium infantis. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Carranza, P.; Jattar-Santiago, K.Y.; Avila-Sosa, R.; Pérez-Xochipa, I.; Guerrero-Beltrán, J.A.; Ochoa-Velasco, C.E.; Ruiz-López, I.I. Antioxidant fortification of yogurt with red cactus pear peel and its mucilage. CYTA J. Food 2019, 17, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Speranza, B.; Bevilacqua, A.; Campaniello, D.; Sinigaglia, M.; Musaico, D.; Corbo, M.R.; Lamacchia, C. The impact of Gluten Friendly flour on the functionality of an active drink: Viability of Lactobacillus acidophilus in a fermented milk. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, T.N.; Junqueira, L.A.; Prado, M.E.T.; Cirillo, M.A.; de Abreu, L.R.; Costa, F.F.; de Resende, J.V. Blends of Pereskia aculeata Miller mucilage, guar gum, and gum Arabic added to fermented milk beverages. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 79, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.A.; Valente, G.D.F.S.; Assumpção, G.M.P. External preference map to evaluate the acceptance of light and diet yogurt preparedusingnatural sweeteners. Cienc. Rural 2018, 48, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Getu, R.; Tola, Y.B.; Neela, S. Optimization of soy milk, mango nectar and sucrose solution mixes for a better quality soy milk-based beverage. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 2017, 16, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dahlan, H.A.; Sani, N.A. The interaction effect of mixing starter cultures on homemade natural yogurt’s pH and viscosity. Int. J. Food Stud. 2017, 6, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudha, A.; Priyenka Devi, K.S.; Sangeetha, V.; Sangeetha, A. Development of fermented millet sprout milk beverage based on physicochemical property studies and consumer acceptability data. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2016, 75, 239–243. [Google Scholar]

- Quijano-Aviles, M.F.; Franco-Agurto, G.L.; Suárez-Quirumbay, K.B.; Barragán-Lucas, A.D.; Manzano-Santana, P.I. Linear programming formulation of a dairy drink made of cocoa, coffee and orange by-products. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2016, 28, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gama, A.P.; Hung, Y.C.; Adhikari, K. Optimization of emulsifier and stabilizer concentrations in a model peanut-based beverage system: A mixture design approach. Foods 2019, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zendeboodi, F.; Yeganehzad, S.; Sadeghian, A. Optimizing the formulation of a natural soft drink based on biophysical properties using mixture design methodology. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 12, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcheafave, G.G.; Pauli, E.D.; Tormena, C.D.; Mattos, L.E.; de Almeida, A.G.; Rakocevic, M.; Bruns, R.E.; Scarminio, I.S. Irrigated and CO2 level effects on metabolism in Coffea arabica beans from mixture design—Near infrared fingerprints. Microchem. J. 2020, 152, 104276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, W.; Capitaine, C.; Rodríguez, R.; Araya-Durán, I.; González-Nilo, F.; Pérez-Correa, J.R.; Agosin, E. Selecting optimal mixtures of natural sweeteners for carbonated soft drinks through multi-objective decision modeling and sensory validation. J. Sens. Stud. 2018, 33, e12466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.D.O.; Dos Santos, J.G.C.; Gomes, F.D.S.; Cabral, L.M.C.; Sá, D.D.G.C.F.; da Matta, V.M.; Freitas, S.P. Sensory evaluation and antioxidant capacity as quality parameters in the development of a banana, strawberry and juçara smoothie. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 38, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salamanca-Neto, C.A.R.; Marcheafave, G.G.; Scremin, J.; Barbosa, E.C.M.; Camargo, P.H.C.; Dekker, R.F.H.; Scarmínio, I.S.; Barbosa-Dekker, A.M.; Sartori, E.R. Chemometric-assisted construction of a biosensing device to measure chlorogenic acid content in brewed coffee beverages to discriminate quality. Food Chem. 2020, 315, 126306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.S.; Deolindo, C.T.P.; Hoffmann, J.F.; Chaves, F.C.; do Prado-Silva, L.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Azevedo, L.; do Carmo, M.A.V.; Granato, D. Optimized Camellia sinensis var. sinensis, Ilex paraguariensis, and Aspalathus linearis blend presents high antioxidant and antiproliferative activities in a beverage model. Food Chem. 2018, 254, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, K.W.; Mirhosseini, H.; Tabatabaee Amid, B.; Sheikh Abdul Hamid, N.; Tan, C.P. The influence of main emulsion components on the physicochemical properties of soursop beverage emulsions: A mixture design approach. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2018, 39, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.B.; Ko, J.Y.; Lim, S. Bin formulation optimization of antioxidant-rich juice powders based on experimental mixture design. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curi, P.N.; de Almeida, A.B.; Tavares, B.D.S.; Nunes, C.A.; Pio, R.; Pasqual, M.; de Souza, V.R. Optimization of tropical fruit juice based on sensory and nutritional characteristics. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 37, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siche, R.; Ávalos, C.; Arteaga, H.; Saldaña, E.; Vieira, T.M.F.S. Antioxidant capacity of binary and ternary mixtures of orange, grape, and starfruit juices. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2015, 12, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntsoane, M.L.; Sivakumar, D.; Mahajan, P.V. Optimisation of O2 and CO2 concentrations to retain quality and prolong shelf life of ‘shelly’ mango fruit using a simplex lattice mixture design. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 192, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, I.; Li, M.; Mamet, T.; Li, C. Maltodextrin or gum Arabic with whey proteins as wall-material blends increased the stability and physiochemical characteristics of mulberry microparticles. Food Biosci. 2019, 31, 100445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, S.; Ahmad, T.; Nisa, M.U.; Imran, M.; Holmes, M.; Maycock, J.; Nadeem, M.; Khan, M.K. Microwave processing impact on physicochemical and bioactive attributes of optimized peach functional beverage. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e13952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Hamid, N.; Gutierrez-Maddox, N.; Kantono, K.; Kitundu, E. Development of a probiotic beverage using breadfruit flour as a substrate. Foods 2019, 8, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Lima, N.D.; Afonso, M.R.A.; da Costa, J.M.C.; Carvalho, J.D.G. Powdered beverage mix with acerola pulp, whey and maltodextrin. Rev. Cienc. Agron. 2019, 50, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.K.; Asif, M.N.; Ahmad, M.H.; Imran, M.; Arshad, M.S.; Hassan, S.; Khan, M.I.; Nisa, M.U.; Iqbal, M.M.; Muhammad, N. Ultrasound-assisted optimal development and characterization of stevia-sweetened functional beverage. J. Food Qual. 2019, 2019, 5916097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schiassi, M.C.E.V.; Lago, A.M.T.; de Souza, V.R.; dos Santos Meles, J.; de Resende, J.V.; Queiroz, F. Mixed fruit juices from Cerrado: Optimization based on sensory properties, bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2334–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, P.P.L.; Kitts, D.D.; Pratap Singh, A. Natural acidification with low-pH Fruits and incorporation of essential oil constituents for organic preservation of unpasteurized juices. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 2039–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, D.F.; Guedes, W.N.; Pereira, F.M.V. Detection of chemical elements related to impurities leached from raw sugarcane: Use of laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) and chemometrics. Microchem. J. 2018, 137, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, L.; Argel, N.; Andrés, S.C.; Califano, A.N. Sodium-reduced lean sausages with fish oil optimized by a mixture design approach. Meat Sci. 2015, 104, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurain, A.; Noriham, A.; Zainon, M.N. Optimisation of mechanically deboned chicken meat (MDCM) aromatic herbal sausage formulations using simplex-lattice mixture design. Int. Food Res. J. 2018, 25, 1799–1807. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, E.; Siche, R.; da Silva Pinto, J.S.; de Almeida, M.A.; Selani, M.M.; Rios-Mera, J.; Contreras-Castillo, C.J. Optimization of lipid profile and hardness of low-fat mortadella following a sequential strategy of experimental design. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momchilova, M.; Gradinarska, D.; Petrova, T.; Zsivanovits, G.; Bakalov, I.; Penov, N.; Yordanov, D. Inulin and lentil flour as fat replacers in meat-vegetable pâté—A mixture design approach. Carpathian J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 11, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkaew, P.; Naivikul, O. Development of gluten-free batter from three Thai rice cultivars and its utilization for frozen battered chicken nugget. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 3620–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepahpour, S.; Selamat, J.; Khatib, A.; Manap, M.Y.A.; Abdull Razis, A.F.; Hajeb, P. Inhibitory effect of mixture herbs/spices on formation of heterocyclic amines and mutagenic activity of grilled beef. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control. Expo. Risk Assess. 2018, 35, 1911–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Safaei, F.; Abhari, K.; Khosroshahi, N.K.; Hosseini, H.; Jafari, M. Optimisation of functional sausage formulation with konjac and inulin: Using D-Optimal mixture design. Foods Raw Mater. 2019, 7, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velioglu, H.M. Low-fat beef patties with cold-pressed oils optimized by mixture design. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2016, 55, 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, B.; Valdomiro Gonzaga, L.; Fett, R.; Oliveira Costa, A.C. Simplex-centroid design and Derringer’s desirability function approach for simultaneous separation of phenolic compounds from Mimosa scabrella Bentham honeydew honeys by HPLC/DAD. J. Chromatogr. A 2019, 1585, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarbad, H.R.; Mazaheri Tehrani, M.; Rashidi, H. Optimization of gluten-free bread formulation using sorghum, rice, and millet flour by D-optimal mixture design approach. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2019, 21, 101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo-Núñez, Á.; Sahagún, M.; Bravo-Núñez, A.; Gómez, M. Optimisation of protein-enriched gluten-free layer cakes using a mixture design. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtarami, F. Effect of carrot pomace powder and dushab (traditional grape juice concentrate) on the physical and sensory properties of cakes: A combined mixtures design approach. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2019, 15, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduntan, A.O.; Arueya, G.L. Design, formulation, and characterization of a potential ‘whole food’ using fibre rich orange (Citrus sinensis Lin) pomace as base. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre 2019, 17, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohizua, E.R.; Adeola, A.A.; Idowu, M.A.; Sobukola, O.P.; Afolabi, T.A.; Ishola, R.O.; Ayansina, S.O.; Oyekale, T.O.; Falomo, A. Nutrient composition, functional, and pasting properties of unripe cooking banana, pigeon pea, and sweetpotato flour blends. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 5, 750–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rytz, A.; Moser, M.; Lepage, M.; Mokdad, C.; Perrot, M.; Antille, N.; Pineau, N. Using fractional factorial designs with mixture constraints to improve nutritional value and sensory properties of processed food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 58, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.G.; Fratelli, C.; Muniz, D.G.; Capriles, V.D. Mixture design applied to the development of chickpea-based gluten-free bread with attractive technological, sensory, and nutritional quality. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tormena, M.M.L.; de Medeiros, L.T.; de Lima, P.C.; Possebon, G.; Fuchs, R.H.B.; Bona, E. Application of multi-block analysis and mixture design with process variable for development of chocolate cake containing yacon (Smallanthus sonchifolius) and maca (Lepidium meyenii). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 3559–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherie, Z.; Ziegler, G.R.; Fekadu Gemede, H.; Zewdu Woldegiorgis, A. Optimization and modeling of teff-maize-rice based formulation by simplex lattice mixture design for the preparation of brighter and acceptable injera. Cogent Food Agric. 2018, 4, 1443381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, O.J.; Sobukola, O.P.; Sanni, L.O.; Bakare, H.A.; Kajihausa, O.E.; Adebowale, A.R.A.; Tomlins, K. Quality attributes of cassava-fish crackers enriched with different flours: An optimization study by a simplex centroid mixture design. J. Food Process Eng. 2017, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, M.E.E.; Pushpadass, H.A.; Kamaraj, M.; Muthurayappa, M.; Battula, S.N. Application of D-optimal mixture design and fuzzy logic approach in the preparation of chhana podo (baked milk cake). J. Food Process Eng. 2019, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, H.; Bolourian, S.; Shahidi, F. Extending the shelf-life of sponge cake by an optimized level of jujube fruit flour determined using custom mixture design. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 3208–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, J.E.C.; González, L.C.; Loubes, M.A.; Tolaba, M.P. Optimization of rice bread formulation by mixture design and relationship of bread quality to flour and dough attributes. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 113, 108299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loubes, M.A.; Flores, S.K.; Tolaba, M.P. Effect of formulation on rice noodle quality: Selection of functional ingredients and optimization by mixture design. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 69, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, L.G.; Ribeiro, F.L.; Teixeira, G.L.; Molognoni, L.; Nascimento dos Santos, J.; Larroza Nunes, I.; Mara Block, J. The potential of the pecan nut cake as an ingredient for the food industry. Food Res. Int. 2020, 127, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, L.G.; Teixeira, G.L.; Block, J.M. Dataset on the phytochemicals, antioxidants, and minerals contents of pecan nut cake extracts obtained by ultrasound-assisted extraction coupled to a simplex-centroid design. Data Br. 2020, 28, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, A.; Rahman, A.; Amin, M.; Johari, M.; Parid, M. Optimisation of stabiliser combinations in instant ice cream mix powder formulation via mixture design methodology. Int. Food Res. J. 2019, 26, 1689–1698. [Google Scholar]

- Gremski, L.A.; Coelho, A.L.K.; Santos, J.S.; Daguer, H.; Molognoni, L.; do Prado-Silva, L.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; da Silva Rocha, R.; da Silva, M.C.; Cruz, A.G.; et al. Antioxidants-rich ice cream containing herbal extracts and fructooligossaccharides: Manufacture, functional and sensory properties. Food Chem. 2019, 298, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BahramParvar, M.; Tehrani, M.M.; Razavi, S.M.A.; Koocheki, A. Application of simplex-centroid mixture design to optimize stabilizer combinations for ice cream manufacture. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 1480–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Curi, P.N.; de Almeida, A.B.; Pio, R.; Lima, L.C.D.O.; Nunes, C.A.; de Souza, V.R. Optimization of native Brazilian fruit jelly through desirability-based mixture design. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 39, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dlamini, N.P.; Solomon, W.K. Optimization of blending ratios of jam from swazi indigenous fruits tincozi (syzygium cordatum), tineyi (phyllogeiton zeyheri) and umfomfo (cephalanthus natalensis oliv.) using mixture design. Cogent Food Agric. 2019, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magomedov, G.O.; Zhuravlev, A.A.; Lobosova, L.A.; Zhurakhova, S.N. Optimization of prescription composition of jelly masses using the Scheffe’s symplex plan. Foods Raw Mater. 2018, 6, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiassi, M.C.E.V.; Salgado, D.L.; Meirelles, B.S.; Lago, A.M.T.; Queiroz, F.; Curi, P.N.; Pio, R.; de Souza, V.R. Berry Jelly: Optimization through desirability-based mixture design. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 1522–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tontul, I.; Topuz, A. Production of pomegranate fruit leather (pestil) using different hydrocolloid mixtures: An optimization study by mixture design. J. Food Process Eng. 2018, 41, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, S.M.; Diako, C.; Ross, C.F. Identification of a Salt Blend: Application of the electronic tongue, consumer evaluation, and mixture design methodology. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes Filho, M.L.; Busanello, M.; Prudencio, S.H.; Garcia, S. Soymilk with okara flour fermented by Lactobacillus acidophilus: Simplex-centroid mixture design applied in the elaboration of probiotic creamy sauce and storage stability. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 93, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhart, A.D.; Ferreira da Silveira, T.F.; Rosa de Moraes, M.; Petrarca, M.H.; Silva, L.H.; Oliveira, W.S.; Wagner, R.; André Bolini, H.M.; Bruns, R.E.; Filho, J.T.; et al. Optimization of frying oil composition rich in essential fatty acids by mixture design. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 84, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saoudi, S.; Chammem, N.; Sifaoui, I.; Jiménez, I.A.; Lorenzo-Morales, J.; Piñero, J.E.; Bouassida-Beji, M.; Hamdi, M.; LBazzocchi, I. Combined effect of carnosol, rosmarinic acid and thymol on the oxidative stability of soybean oil using a simplex centroid mixture design. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 3300–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Gleize, B.; Zhang, L.; Caris-Veyrat, C.; Renard, C.M.G.C. A D-optimal mixture design of tomato-based sauce formulations: Effects of onion and EVOO on lycopene isomerization and bioaccessibility. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 3589–3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, B.; Katare, O.P.; Beg, S.; Lohan, S.; Singh, B. Systematic development of solid self-nanoemulsifying oily formulations (S-SNEOFs) for enhancing the oral bioavailability and intestinal lymphatic uptake of lopinavir. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2016, 141, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, B.; Beg, S.; Kaur, R.; Kumar, R.; Katare, O.P.; Singh, B. Long-chain triglycerides-based self-nanoemulsifying oily formulations (SNEOFs) of darunavir with improved lymphatic targeting potential. J. Drug Target. 2018, 26, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Godoi, K.R.R.; Basso, R.C.; Ming, C.C.; da Silva, V.M.; da Cunha, R.L.; Barrera-Arellano, D.; Ribeiro, A.P.B. Physicochemical and rheological properties of soybean organogels: Interactions between different structuring agents. Food Res. Int. 2019, 124, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granillo-Guerrero, V.G.; Villalobos-Espinosa, J.C.; Alamilla-Beltrán, L.; Téllez-Medina, D.I.; Hernández-Sánchez, H.; Dorantes-Álvarez, L.; Gutiérrez-López, G.F. Optimization of the formulation of emulsions prepared with a mixture of vitamins d and e by means of an experimental design simplex centroid and analysis of colocalization of its components. Rev. Mex. Ing. Química 2017, 16, 861–872. [Google Scholar]

- Al Hagbani, T.; Altomare, C.; Salawi, A.; Nazzal, S. D-optimal mixture design: Formulation development, mechanical characterization, and optimization of curcumin chewing gums using oppanol® B 12 elastomer as a gum-base. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 553, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasa, D.; Perissutti, B.; Campisi, B.; Grassi, M.; Grabnar, I.; Golob, S.; Mian, M.; Voinovich, D. Quality improvement of melt extruded laminar systems using mixture design. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 75, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isailović, T.; Dordević, S.; Marković, B.; Randelovic, D.; Cekić, N.; Lukić, M.; Pantelić, I.; Daniels, R.; Savić, S. Biocompatible nanoemulsions for improved aceclofenac skin delivery: Formulation Approach using combined mixture-process experimental design. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 105, 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamboj, S.; Sharma, R.; Singh, K.; Rana, V. Aprepitant loaded solid preconcentrated microemulsion for enhanced bioavailability: A comparison with micronized Aprepitant. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 78, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamboj, S.; Rana, V. Quality-by-design based development of a self-microemulsifying drug delivery system to reduce the effect of food on Nelfinavir mesylate. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 501, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, R.K.; Beg, S.; Burrow, A.J.; Vashishta, R.K.; Katare, O.P.; Kaur, S.; Kesharwani, P.; Singh, K.K.; Singh, B. Enhancing biopharmaceutical performance of an anticancer drug by long chain PUFA based self-nanoemulsifying lipidic nanomicellar systems. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017, 121, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lima, S.G.B.; Pinho, L.A.G.; Pereira, M.N.; Gratieri, T.; Sa-Barreto, L.L.; Gelfuso, G.M.; Cunha-Filho, M. Preformulation studies of finasteride to design matrix systems for topical delivery. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 161, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaquias, L.F.B.; Schulte, H.L.; Chaker, J.A.; Karan, K.; Durig, T.; Marreto, R.N.; Gratieri, T.; Gelfuso, G.M.; Cunha-Filho, M. Hot melt extrudates formulated using design space: One Simple process for both palatability and dissolution rate improvement. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 107, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mori, M.; Rossi, S.; Ferrari, F.; Bonferoni, M.C.; Sandri, G.; Chlapanidas, T.; Torre, M.L.; Caramella, C. Sponge-like dressings based on the association of chitosan and sericin for the treatment of chronic skin ulcers. I. design of experiments-assisted development. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 105, 1180–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, R.; Sen, K.; Fontana, L.; Mao, C.; Chaudhuri, B. Quantification of moisture-induced cohesion in pharmaceutical mixtures. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Patel, M.B.; Shaikh, F.; Patel, V.; Surti, N.I. Application of simplex centroid design in formulation and optimization of floating matrix tablets of metformin. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 7, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, F.Q.; Angelo, T.; Silva, J.K.R.; Sá-Barreto, L.C.L.; Lima, E.M.; Gelfuso, G.M.; Gratieri, T.; Cunha-Filho, M.S.S. Use of mixture design in drug-excipient compatibility determinations: Thymol nanoparticles case study. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2017, 137, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Barot, T.; Rajesh, K.S.; Jha, L.L. Formulation, optimization and evaluation of microemulsion based gel of Butenafine Hydrochloride for topical delivery by using simplex lattice mixture design. J. Pharm. Investig. 2016, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, N.; Sepúlveda, C.; Arancibia, C. Influence of ternary emulsifier mixtures on oxidative stability of nanoemulsions based on avocado oil. Foods 2020, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rossi, S.; Vigani, B.; Puccio, A.; Bonferoni, M.C.; Sandri, G.; Ferrari, F. Chitosan ascorbate nanoparticles for the vaginal delivery of antibiotic drugs in atrophic vaginitis. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shah, N.; Seth, A.; Balaraman, R.; Sailor, G.; Javia, A.; Gohil, D. Oral bioavailability enhancement of raloxifene by developing microemulsion using D-optimal mixture design: Optimization and in-vivo pharmacokinetic study. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2018, 44, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apeji, Y.E.; Oyi, A.R.; Isah, A.B.; Allagh, T.S.; Modi, S.R.; Bansal, A.K. Development and optimization of a starch-based co-processed excipient for direct compression using mixture design. AAPS PharmSciTech 2018, 19, 866–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisinthy, S.P.; Lynn Sarah, C.Y.; Rao, N.K. Optimization of coconut oil based self micro emulsifying drug delivery systems of olmesartan medoxomil by simplex centroid design. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. 2016, 8, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.Y.; Chae, B.R.; Choi, J.Y.; Shin, D.J.; Goo, Y.T.; Lee, E.S.; Kang, T.H.; Kim, C.H.; Yoon, H.Y.; Choi, Y.W. Optimization of self-microemulsifying drug delivery system for phospholipid complex of telmisartan using D-optimal mixture design. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tibalinda, P.; Sempombe, J.; Shedafa, R.; Masota, N.; Pius, D.; Temu, M.; Kaale, E. Formulation development and optimization of Lamivudine 300 mg and Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (TDF) 300 mg FDC tablets by D-optimal mixture design. Heliyon 2016, 2, e00207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Visetvichaporn, V.; Kim, K.H.; Jung, K.; Cho, Y.S.; Kim, D.D. Formulation of self-microemulsifying drug delivery system (SMEDDS) by D-optimal mixture design to enhance the oral bioavailability of a new cathepsin K inhibitor (HL235). Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 573, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winarti, L.; Martien, R.; Suwaldi; Hakim, L. An experimental design of SNEDDS template loaded with bovine serum albumin and optimization using D-optimal. Int. J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2016, 8, 425–432. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Dunn, C.; Khadra, I.; Wilson, C.G.; Halbert, G.W. Influence of physiological gastrointestinal surfactant ratio on the equilibrium solubility of BCS class II drugs investigated using a four component mixture design. Mol. Pharm. 2017, 14, 4132–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ashara, K.C.; Shah, K.V. Nuts and bolts of oil and temperature in topical preparations of salicylic acid. Folia Med. 2017, 59, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bennani, I.; Yachi, L.; Bennis, S.; Mefetah, H.; Cheikh, A.; Bouatia, M.; Rahali, Y. Oleogels based on vegetable oil and synthetic oil: Evaluation of the effect of the bentone on gelling using a mixture design. Asian J. Pharm. 2018, 12, 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Bennis, S.; Yachi, L.; Elalaoui, Y.; Bouatia, M.; Cherkaoui, N.; Laatiris, A.; Rahali, Y. Evaluation of the effect of the Organo-bentonite on gelification of Almond oil using a mixture design. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2017, 8, 2506–2512. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, S.I.; Nathwani, S.V.; Soniwala, M.M.; Chavda, J.R. Development and characterization of multifunctional directly compressible Co-processed excipient by spray drying method. AAPS PharmSciTech 2017, 18, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, A.M.; Tan, K.W.; Tan, C.P.; Nyam, K.L. Improvement of physical stability properties of kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.) seed oil-in-water nanoemulsions. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016, 80, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkomy, M.H.; El Menshawe, S.F.; Abou-Taleb, H.A.; Elkarmalawy, M.H. Loratadine bioavailability via buccal transferosomal gel: Formulation, statistical optimization, in vitro/in vivo characterization, and pharmacokinetics in human volunteers. Drug Deliv. 2017, 24, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noghabi, M.S.; Molaveisi, M. Microencapsulation optimization of cinnamon essential oil in the matrices of gum Arabic, maltodextrin, and inulin by spray-drying using mixture design. J. Food Process Eng. 2019, 43, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Araujo Santiago, M.C.P.; Nogueira, R.I.; Paim, D.R.S.F.; Gouvêa, A.C.M.S.; Godoy, R.L.D.O.; Peixoto, F.M.; Pacheco, S.; Freitas, S.P. Effects of encapsulating agents on anthocyanin retention in pomegranate powder obtained by the spray drying process. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 73, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorasani, A.C.; Shojaosadati, S.A. Bacterial nanocellulose-pectin bionanocomposites as prebiotics against drying and gastrointestinal condition. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 83, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranauskaite, J.; Ivanauskas, L.; Masteikova, R.; Kopustinskiene, D.; Baranauskas, A.; Bernatoniene, J. Formulation and characterization of Turkish oregano microcapsules prepared by spray-drying technology. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2017, 22, 792–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosli, N.A.; Hasham, R.; Aziz, A. Design and physicochemical evaluation of nanostructured lipid carrier encapsulated zingiber zerumbet oil by d- optimal mixture design. J. Teknol. 2018, 3, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Othman, N.Z.; Shadan, N.H.; Ramli, S.; Sarmidi, M.R. Study on the effects of carbohydrate-protein-coconut oil on the viability of lactobacillus bulgaricus during spray drying, simulated gastrointestinal conditions and unrefrigerated storage by simplex-lattice mixture design. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2018, 63, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paludo, M.C.; Colombo, R.C.; Filho, J.T.; Hermosín-Gutiérrez, I.; Ballus, C.A.; Godoy, H.T. Optimizing the extraction of anthocyanins from the skin and phenolic compounds from the seed of jabuticaba fruits (Myrciaria jabuticaba o (Vell.) O. Berg) with ternary mixture experimental designs. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2019, 30, 1506–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araromi, D.O.; Alade, A.O.; Bello, M.O.; Bakare, T.; Akinwande, B.A.; Jameel, A.T.; Adegbola, S.A. Optimization of oil extraction from Pitanga (Eugenia uniflora L.) leaves using simplex centroid design. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.A.; Abu Bakar, M.F.; Kormin, F.; Linatoc, A.C.; Mohamed, M. Application of statistically simplex-centroid mixture design to optimize the TPC and TFC on the proportion of polyherbal formulation used by jakun women. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2018, 13, 6996–7002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Archivio, A.A.; Maggi, M.A.; Ruggieri, F. Extraction of curcuminoids by using ethyl lactate and its optimisation by response surface methodology. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 149, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidelis, M.; do Carmo, M.A.V.; da Cruz, T.M.; Azevedo, L.; Myoda, T.; Miranda Furtado, M.; Boscacci Marques, M.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Inês Genovese, M.; Young Oh, W.; et al. Camu-camu seed (Myrciaria dubia)—From side stream to an antioxidant, antihyperglycemic, antiproliferative, antimicrobial, antihemolytic, anti-inflammatory, and antihypertensive ingredient. Food Chem. 2020, 310, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, P.R.N.; de Freitas, F.A.; Angolini, C.F.F.; Vasconcelos, L.S.F.; da Silva, A.L.B.; Costa, E.V.; da Silva, F.M.A.; Eberlin, M.N.; Bataglion, G.A.; Soares, P.K.; et al. Statistical mixture design investigation for extraction and quantitation of aporphine alkaloids from the leaves of Unonopsis duckei R.E. Fr. by HPLC–MS/MS. Phytochem. Anal. 2018, 29, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falleh, H.; Ben Jemaa, M.; Djebali, K.; Abid, S.; Saada, M.; Ksouri, R. Application of the mixture design for optimum antimicrobial activity: Combined treatment of Syzygium aromaticum, Cinnamomum zeylanicum, Myrtus communis, and Lavandula stoechas essential oils against Escherichia coli. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, Y.A.; Bravo Sánchez, L.R.; Quintana, Y.G.; Cabrera, A.S.T.; Bermúdez del Sol, A.; Mayancha, D.M.G. Evaluation of the synergistic effects of antioxidant activity on mixtures of the essential oil from Apium graveolens L., Thymus vulgaris L. and Coriandrum sativum L. using simplex-lattice design. Heliyon 2019, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baj, T.; Baryluk, A.; Sieniawska, E. Application of mixture design for optimum antioxidant activity of mixtures of essential oils from Ocimum basilicum L., Origanum majorana L. and Rosmarinus officinalis L. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2018, 115, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadil, M.; Fikri-Benbrahim, K.; Rachiq, S.; Ihssane, B.; Lebrazi, S.; Chraibi, M.; Haloui, T.; Farah, A. Combined treatment of Thymus vulgaris L., Rosmarinus officinalis L. and Myrtus communis L. essential oils against Salmonella typhimurium: Optimization of antibacterial activity by mixture design methodology. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 126, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouedrhiri, W.; Balouiri, M.; Bouhdid, S.; Moja, S.; Chahdi, F.O.; Taleb, M.; Greche, H. Mixture design of Origanum compactum, Origanum majorana and Thymus serpyllum essential oils: Optimization of their antibacterial effect. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016, 89, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolmeh, M.; Khomeiri, M.; Ahmadi, Z. Application of mixture design to introduce an optimum cell-free supernatant of multiple-strain mixture (MSM) for Lactobacillus against food-borne pathogens. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 83, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Roman, I.; Garcia-Rodriguez, J.J.; Kiekens, F.; Cordoba-Diaz, D.; Cordoba-Diaz, M. Enhanced nematocidal activity of a novel Artemisia extract formulated as a microemulsion. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenci, M.; Rossi, S.; Giannino, V.; Vigani, B.; Sandri, G.; Bonferoni, M.C.; Daglia, M.; Longo, L.M.; Macelloni, C.; Ferrari, F. An in situ gelling system for the local treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). the loading of maqui (aristotelia chilensis) berry extract as an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agent. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castro, R.J.S.; Inacio, R.F.; de Oliveira, A.L.R.; Sato, H.H. Statistical optimization of protein hydrolysis using mixture design: Development of efficient systems for suppression of lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2016, 5, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C.M.; Benelli, P.; Tessaro, I.C. Constrained mixture design to optimize formulation and performance of foams based on cassava starch and peanut skin. J. Polym. Environ. 2019, 27, 2224–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravartula, S.S.N.; Soccio, M.; Lotti, N.; Balestra, F.; Dalla Rosa, M.; Siracusa, V. Characterization of composite edible films based on pectin/alginate/whey protein concentrate. Materials 2019, 12, 2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Díaz, E.L.; Padilla Camberos, E.; Castillo Herrera, G.A.; Estarrón Espinosa, M.; Espinosa Andrews, H.; Paniagua Buelnas, N.A.; Gutiérrez Ortega, A.; Martínez Velázquez, M. Development of essential oil-based phyto-formulations to control the cattle tick Rhipicephalus microplus using a mixture design approach. Exp. Parasitol. 2019, 201, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Hong, H.; Kim, J.C.; Lim, T.G.; Song, Y.R.; Cho, C.W.; Jang, M. Mixing ratio optimization for functional complex extracts of Rhodiola crenulata, Panax quinquefolius, and Astragalus membranaceus using mixture design and verification of immune functional efficacy in animal models. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 40, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teglia, C.M.; Peltzer, P.M.; Seib, S.N.; Lajmanovich, R.C.; Culzoni, M.J.; Goicoechea, H.C. Simultaneous multi-residue determination of twenty one veterinary drugs in poultry litter by modeling three-way liquid chromatography with fluorescence and absorption detection data. Talanta 2017, 167, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arous, F.; Frikha, F.; Triantaphyllidou, I.E.; Aggelis, G.; Nasri, M.; Mechichi, T. Potential utilization of agro-industrial wastewaters for lipid production by the oleaginous yeast Debaryomyces etchellsii. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredda, E.H.; Da Silva, A.F.; Silva, M.B.; Da Rós, P.C.M. Mixture design as a potential tool in modeling the effect of light wavelength on Dunaliella salina cultivation: An alternative solution to increase microalgae lipid productivity for biodiesel production. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2019, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Cai, Y.; Li, X.; Jiao, L.; Xia, J.; Deng, X. Effects of the cellulose, xylan and lignin constituents on biomass pyrolysis characteristics and bio-oil composition using the Simplex Lattice Mixture Design method. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 138, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, A.C.S.; Alvarez, L.D.G.; Santana, R.A.; Valasques, G.L., Jr.; Bezerra, M.A.; de Oliveira Neto, N.M.; de Oliveira Lima, E.; de Oliveira Filho, A.A.; Franco, M.; do Nascimento, B.B., Jr. Application of experimental designs to evaluate the total phenolics content and antioxidant activity of cashew apple bagasse. Rev. Mex. Ing. Quim. 2018, 17, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashi, S.; Satari, B.; Lundin, M.; Horváth, I.S.; Othman, M. Application of a mixture design to identify the effects of substrates ratios and interactions on anaerobic co-digestion of municipal sludge, grease trap waste, and meat processing waste. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 6156–6164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat, S.C.; Idroas, M.Y.; Teoh, Y.H.; Hamid, M.F. Optimisation of viscosity and density of refined palm Oil-Melaleuca Cajuputi oil binary blends using mixture design method. Renew. Energy 2019, 133, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouadjep, N.S.; Nso, E.; Gueguim Kana, E.B.; Kapseu, C. Simplex lattice mixture design application for biodiesel production: Formulation and characterization of hybrid oil as feedstock. Fuel 2019, 252, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valasques, G.S.; Dos Santos, A.M.P.; Da Silva, D.G.; Alves, J.P.S.; Bezerra, M.A. Use of constrained mixture design in the optimization of a method based on extraction induced by emulsion breaking for the determination of Ca, Mg, Mn, Fe and Zn from palm oil by flame atomic absorption spectrometry. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2018, 29, 2189–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Cao, H.; Yuan, Q.; Luoa, S.; Liu, Z. Component optimization of dairy manure vermicompost, straw, and peat in seedling compressed substrates using simplex-centroid design. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2018, 68, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Cardozo, J.; Quintanilla-Carvajal, M.X.; Ruiz-Pardo, R.; Acosta-González, A. Evaluating gelling-agent mixtures as potential substitutes for bacteriological agar: An approach by mixture design. DYNA 2019, 86, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passari, L.M.Z.G.; Scarminio, I.S.; Marcheafave, G.G.; Bruns, R.E. Seasonal changes and solvent effects on fractionated functional food component yields from Mikania laevigata leaves. Food Chem. 2019, 273, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, A.L.B.; dos Santos, M.K.; Limberger, R.P. Development and validation of a method using dried oral fluid spot to determine drugs of abuse. J. Forensic Sci. 2019, 64, 1906–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annamalai, M.; Ramasubbu, R. Optimizing the formulation of E-glass fiber and cotton shell particles hybrid composites for their mechanical behavior by mixture design analysis. Mater. Tehnol. 2018, 52, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varanda, C.; Portugal, I.; Ribeiro, J.; Silva, A.M.S.; Silva, C.M. Optimization of bitumen formulations using mixture design of experiments (MDOE). Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 156, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilian, H.; Semnani, A.; Haddadi, H.; Nekoeinia, M. Multiresponse optimization of a hydraulic oil formulation by mixture design and response surface methods. J. Tribol. 2016, 138, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, Y.B.; Celik, O.N.; Burnak, N.; Demirtas, E.A. Modeling and analysis of the effects of nano-oil additives on wear properties of AISI 4140 steel material using mixture design. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2016, 230, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.C.; Fontes, M.P.F.; Reis, C.; Bellato, C.R.; Fendorf, S. Simplex-Centroid mixture design applied to arsenic (V) removal from waters using synthetic minerals. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 238, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derringer, G.; Suich, R. Simultaneous optimization of several response variables. J. Qual. Technol. 1980, 12, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Countries | UN | Countries | UN | Countries | UN | Countries | UN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | AFG | Ecuador | ECU | Japan | JPN | Serbia | SRB |

| Argentina | ARG | Eswatini | SWZ | Lithuania | LTU | Singapore | SGP |

| Australia | AUS | Ethiopia | ETH | Malaysia | MYL | South Africa | ZAF |

| Belgium | BEL | Finland | FIN | Morocco | MAR | South Korea | KOR |

| Brazil | BRA | France | FRA | Mexico | MEX | Spain | ESP |

| Bulgaria | BGR | Germany | DEU | New Zealand | NZL | Sweden | SWE |

| Cameroon | CMR | Greece | GRC | Nigeria | NER | Switzerland | CHE |

| Canada | CAN | Hong Kong | HKG | Pakistan | PAK | Tanzania | TZA |

| Chile | CHL | India | IND | Peru | PER | Thailand | THA |

| China | CHN | Indonesia | IDN | Poland | POL | Tunisia | TUN |

| Colombia | COL | Iran | IRN | Portugal | PRT | Turkey | TUR |

| Czech Republic | CZE | Ireland | IRL | Russian | RUS | United Kingdom | GBR |

| Egypt | EGY | Italy | ITA | Saudi Arabia | SAU | United States | USA |

| Papers | nref | References for Data Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Application in Beverage | 37 | Refs. |

| Alcoholic beverage | 1 | [43] |

| Milk-based beverages | 14 | [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57] |

| Several beverages | 9 | [25,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65] |

| Several juices | 13 | [24,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77] |

| Papers | nref | References for Data Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Application in Food | 39 | Refs. |

| Animal origin | 10 | [26,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86] |

| Bakery product | 16 | [87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102] |

| Dairy frozen | 3 | [103,104,105] |

| Fruit jelly | 5 | [106,107,108,109,110] |

| Vegetable origin | 5 | [111,112,113,114,115] |

| Papers | nref | References for Data Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Application in Pharmaceutical Health | 59 | Refs. |

| Drug formulation | 36 | [23,27,28,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148] |

| Encapsulation | 6 | [149,150,151,152,153,154] |

| Extraction compounds | 6 | [155,156,157,158,159,160] |

| Functional activity | 9 | [161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169] |

| Foams/films-based | 2 | [170,171] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galvan, D.; Effting, L.; Cremasco, H.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Recent Applications of Mixture Designs in Beverages, Foods, and Pharmaceutical Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Foods 2021, 10, 1941. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10081941

Galvan D, Effting L, Cremasco H, Conte-Junior CA. Recent Applications of Mixture Designs in Beverages, Foods, and Pharmaceutical Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Foods. 2021; 10(8):1941. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10081941

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalvan, Diego, Luciane Effting, Hágata Cremasco, and Carlos Adam Conte-Junior. 2021. "Recent Applications of Mixture Designs in Beverages, Foods, and Pharmaceutical Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Foods 10, no. 8: 1941. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10081941