Food Emulsifiers and Metabolic Syndrome: The Role of the Gut Microbiota

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

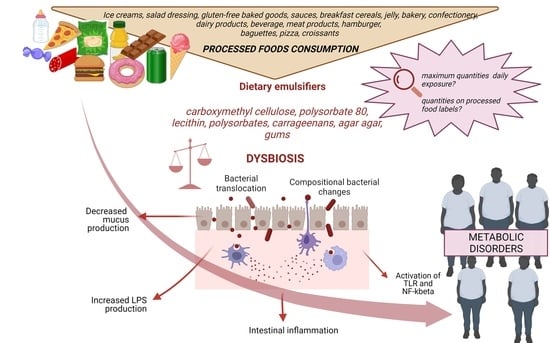

3. Emulsifiers in Processed Foods

3.1. Emulsifiers Classification, Safety Legislation, and Labeling: State-of-the-Art and Limitations

3.2. Common Emulsifiers Used in the Food Supply

3.2.1. Carboxymethylcellulose (CMC)

3.2.2. Polysorbate 80 (P80)

3.2.3. Lecithins

3.2.4. Propylene Glycol Alginate

3.2.5. Carrageenans

3.2.6. Gums (Acacia, Arabic, Xanthan, Guar)

3.2.7. Maltodextrin

3.2.8. Agar Agar

3.2.9. Glycerol Monolaurate

3.2.10. Rhamnolipids and Sophorolipids

4. Gut Microbiota and Metabolic Syndrome

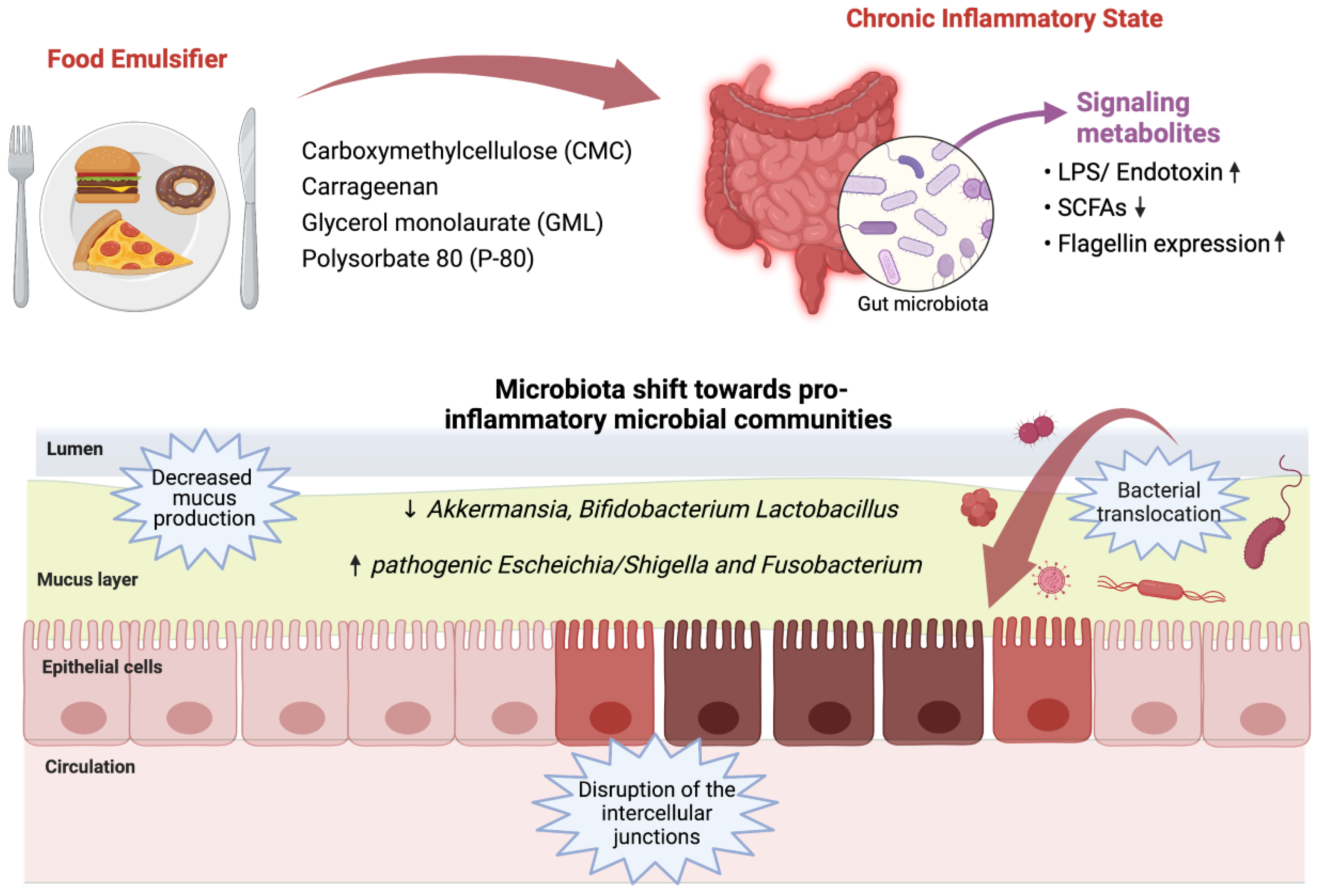

5. Relationship between Emulsifiers and Metabolic Syndrome through Gut Microbiota

5.1. In Vitro Studies

5.2. Animal Studies

5.3. Human Studies

6. Not All So Bad: Emulsifiers to Date Considered Safe

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lawrence, M.A.; Baker, P.I. Ultra-processed food and adverse health outcomes. BMJ 2019, 365, l2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahed, G.; Aoun, L.; Bou Zerdan, M.; Allam, S.; Bou Zerdan, M.; Bouferraa, Y.; Assi, H.I. Metabolic Syndrome: Updates on Pathophysiology and Management in 2021. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saklayen, M.G. The Global Epidemic of the Metabolic Syndrome. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2018, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guembe, M.J.; Fernandez-Lazaro, C.I.; Sayon-Orea, C.; Toledo, E.; Moreno-Iribas, C.; for the RIVANA Study Investigators; Cosials, J.B.; Reyero, J.B.; Martínez, J.D.; Diego, P.G.; et al. Risk for Cardiovascular Disease Associated with Metabolic Syndrome and Its Components: A 13-Year Prospective Study in the RIVANA Cohort. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.-A.; Lee, J.-H.; Lim, S.-Y.; Ha, H.-S.; Kwon, H.-S.; Park, Y.-M.; Lee, W.-C.; Kang, M.-I.; Yim, H.-W.; Yoon, K.-H.; et al. Metabolic Syndrome as a Predictor of Type 2 Diabetes, and Its Clinical Interpretations and Usefulness. J. Diabetes Investig. 2013, 4, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaGuardia, H.A.; Hamm, L.L.; Chen, J. The Metabolic Syndrome and Risk of Chronic Kidney Disease: Pathophysiology and Intervention Strategies. J. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 2012, 652608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esposito, K.; Chiodini, P.; Colao, A.; Lenzi, A.; Giugliano, D. Metabolic Syndrome and Risk of Cancer. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 2402–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cao, C.; Zhu, H.; Yao, Y.; Zeng, R. Gut Dysbiosis and Kidney Diseases. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 829349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldeamlak, B.; Yirdaw, K.; Biadgo, B. Role of Gut Microbiota in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications: Novel Insights and Potential Intervention Strategies. Korean J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 74, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.R.; Singh, M.; Kumar, V.; Yadav, M.; Sehrawat, N.; Sharma, D.K.; Sharma, A.K. Microbiome Dysbiosis in Cancer: Exploring Therapeutic Strategies to Counter the Disease. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 70, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazelas, E.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Esseddik, Y.; de Edelenyi, F.S.; Agaesse, C.; De Sa, A.; Lutchia, R.; Rebouillat, P.; Srour, B.; Debras, C.; et al. Exposure to Food Additive Mixtures in 106,000 French Adults from the NutriNet-Santé Cohort. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, D.; Lloyd, K.A.; Rhodes, J.M.; Walker, A.W.; Johnstone, A.M.; Campbell, B.J. Food Additives: Assessing the Impact of Exposure to Permitted Emulsifiers on Bowel and Metabolic Health—Introducing the FADiets Study. Nutr. Bull. 2019, 44, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fao.Org. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/en/ (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Food.Gov.Uk. Available online: https://www.food.gov.uk/business-guidance/approved-additives-and-e-numbers#emulsifiers-stabilisers-thickeners-and-gelling-agents (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Flavourings (FAF); Younes, M.; Aquilina, G.; Castle, L.; Engel, K.; Fowler, P.; Frutos Fernandez, M.J.; Fürst, P.; Gürtler, R.; Husøy, T.; et al. Opinion on the Re-evaluation of Lecithins (E 322) as a Food Additive in Foods for Infants below 16 Weeks of Age and Follow-up of Its Re-evaluation as Food Additive for Uses in Foods for All Population Groups. EFS2 2020, 18, e06266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mog, S.R.; Zang, Y.J. Safety Assessment of Food Additives: Case Example With Myrcene, a Synthetic Flavoring Agent. Toxicol. Pathol. 2019, 47, 1035–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alger, H.M.; Maffini, M.V.; Kulkarni, N.R.; Bongard, E.D.; Neltner, T. Perspectives on How FDA Assesses Exposure to Food Additives When Evaluating Their Safety: Workshop Proceedings: Food Additives Exposure Proceedings. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2013, 12, 90–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemrah, N.; Leblanc, J.-C.; Volatier, J.-L. Assessment of Dietary Exposure in the French Population to 13 Selected Food Colours, Preservatives, Antioxidants, Stabilizers, Emulsifiers and Sweeteners. Food Addit. Contam. Part B 2008, 1, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, C.; Molinaro, M.G.; Piccinelli, R.; Baldini, M.; Arcella, D.; Stacchini, P. Dietary Intake Exposure to Sulphites in Italy—Analytical Determination of Sulphite-Containing Foods and Their Combination into Standard Meals for Adults and Children. Food Addit. Contam. 2000, 17, 979–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.; Sandall, A.; Smith, L.; Rossi, M.; Whelan, K. Food Additive Emulsifiers: A Review of Their Role in Foods, Legislation and Classifications, Presence in Food Supply, Dietary Exposure, and Safety Assessment. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 726–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arancibia, C.; Navarro-Lisboa, R.; Zúñiga, R.N.; Matiacevich, S. Application of CMC as Thickener on Nanoemulsions Based on Olive Oil: Physical Properties and Stability. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2016, 2016, 6280581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fda.gov. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/generally-recognized-safe-gras/gras-substances-scogs-database (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Inchem.org. Available online: https://inchem.org/documents/jecfa/jecmono/v042je10.htm (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS); Younes, M.; Aggett, P.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; Di Domenico, A.; Dusemund, B.; Filipič, M.; Frutos, M.J.; Galtier, P.; et al. Re-evaluation of Celluloses E 460(i), E 460(Ii), E 461, E 462, E 463, E 464, E 465, E 466, E 468 and E 469 as Food Additives. EFS2 2018, 16, e05047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Accessdata.fda.gov. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/cfrsearch.cfm?fr=172.840 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Yang, N.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, F.-Y.; Gao, H.-T.; Rong, W.-T.; Yu, S.-Q.; Xu, Q. Food Emulsifier Polysorbate 80 Increases Intestinal Absorption of Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate in Rats. Toxicol. Sci. 2014, 139, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS). Scientific Opinion on the Re-evaluation of Polyoxyethylene Sorbitan Monolaurate (E 432), Polyoxyethylene Sorbitan Monooleate (E 433), Polyoxyethylene Sorbitan Monopalmitate (E 434), Polyoxyethylene Sorbitan Monostearate (E 435) and Polyoxyethylene Sorbitan Tristearate (E 436) as Food Additives. EFS2 2015, 13, 4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoogevest, P.; Wendel, A. The Use of Natural and Synthetic Phospholipids as Pharmaceutical Excipients. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2014, 116, 1088–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cabezas, D.M.; Diehl, B.W.K.; Tomás, M.C. Sunflower Lecithin: Application of a Fractionation Process with Absolute Ethanol. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2009, 86, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lončarević, I.; Pajin, B.; Petrović, J.; Zarić, D.; Sakač, M.; Torbica, A.; Lloyd, D.M.; Omorjan, R. The Impact of Sunflower and Rapeseed Lecithin on the Rheological Properties of Spreadable Cocoa Cream. J. Food Eng. 2016, 171, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L. Current Progress in the Utilization of Soy-Based Emulsifiers in Food Applications—A Review. Foods 2021, 10, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Flavourings (FAF); Younes, M.; Aquilina, G.; Castle, L.; Engel, K.; Fowler, P.; Frutos Fernandez, M.J.; Fürst, P.; Gürtler, R.; Gundert-Remy, U.; et al. Safety of Use of Oat Lecithin as a Food Additive. EFS2 2020, 18, 5969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Propylene Glycol Alginate; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1995; Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/jecfa_additives/docs/Monograph1/Additive-360.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS); Younes, M.; Aggett, P.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; Filipič, M.; Frutos, M.J.; Galtier, P.; Gott, D.; Gundert-Remy, U.; et al. Re-evaluation of Propane-1,2-diol Alginate (E 405) as a Food Additive. EFS2 2018, 16, e05371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tobacman, J.K. Review of Harmful Gastrointestinal Effects of Carrageenan in Animal Experiments. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001, 109, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Dudeja, P.K.; Tobacman, J.K. Tumor Necrosis Factor α-Induced Inflammation Is Increased but Apoptosis Is Inhibited by Common Food Additive Carrageenan. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 39511–39522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borthakur, A.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Dudeja, P.K.; Tobacman, J.K. Carrageenan Induces Interleukin-8 Production through Distinct Bcl10 Pathway in Normal Human Colonic Epithelial Cells. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2007, 292, G829–G838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Evaluation of Certain Food Additives and Contaminants: Fifty-Seventh Report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives; World Health Organization: Genewa, Switzerland; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42578 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS); Younes, M.; Aggett, P.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; Filipič, M.; Frutos, M.J.; Galtier, P.; Gott, D.; Gundert-Remy, U.; et al. Re-evaluation of Carrageenan (E 407) and Processed Eucheuma Seaweed (E 407a) as Food Additives. EFS2 2018, 16, e05238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.H.; Ziada, A.; Blunden, G. Biological Effects of Gum Arabic: A Review of Some Recent Research. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.M.W. Evidence for the Safety of Gum Arabic (Acacia Senegal (L.) Willd.) as a Food Additive—A Brief Review. Food Addit. Contam. 1986, 3, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinsky, G.; Halpin, L. The Pastry Chef’s Companion: A Comprehensive Resource Guide for the Baking and Pastry Professional; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2008; Volume 134, p. 1. ISBN 978–0-470–00955–0. OCLC 173182689. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, G.O. Acacia Gum (Gum Arabic): A Nutritional Fibre; Metabolism and Calorific Value. Food Addit. Contam. 1998, 15, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS); Mortensen, A.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; Di Domenico, A.; Frutos, M.J.; Galtier, P.; Gott, D.; Gundert-Remy, U.; Lambré, C.; et al. Re-evaluation of Acacia Gum (E 414) as a Food Additive. EFS2 2017, 15, e04741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, L. Handbook of Water-Soluble Gums and Resins; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980; ISBN 978–0-07–015471–1. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS); Mortensen, A.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; Di Domenico, A.; Frutos, M.J.; Galtier, P.; Gott, D.; Gundert-Remy, U.; Lambré, C.; et al. Re-evaluation of Xanthan Gum (E 415) as a Food Additive. EFS2 2017, 15, e04909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mudgil, D.; Barak, S.; Khatkar, B.S. Guar Gum: Processing, Properties and Food Applications—A Review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goldstein, A.M. Industrial Gums, Polysaccharides and Their Derivatives; Whistler, R., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1959; pp. 343–360. [Google Scholar]

- Gujral, H.S.; Sharma, A.; Singh, N. Effect of hydrocolloids, storage temperature, and duration on the consistency of tomato ketchup. Int. J. Food Prop. 2002, 5, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS); Mortensen, A.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; Di Domenico, A.; Frutos, M.J.; Galtier, P.; Gott, D.; Gundert-Remy, U.; Lambré, C.; et al. Re-evaluation of Guar Gum (E 412) as a Food Additive. EFS2 2017, 15, e04669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hofman, D.L.; van Buul, V.J.; Brouns, F.J.P.H. Nutrition, Health, and Regulatory Aspects of Digestible Maltodextrins. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 2091–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accessdata.fda.gov. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/cfrsearch.cfm?fr=184.1444 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Accessdata.fda.gov. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=184.1115 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Zhang, M.S.; Sandouk, A.; Houtman, J.C.D. Glycerol Monolaurate (GML) Inhibits Human T Cell Signaling and Function by Disrupting Lipid Dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Díaz De Rienzo, M.A.; Banat, I.M.; Dolman, B.; Winterburn, J.; Martin, P.J. Sophorolipid Biosurfactants: Possible Uses as Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Agent. New Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anestopoulos, I.; Kiousi, D.E.; Klavaris, A.; Galanis, A.; Salek, K.; Euston, S.R.; Pappa, A.; Panayiotidis, M.I. Surface Active Agents and Their Health-Promoting Properties: Molecules of Multifunctional Significance. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, M.; Silva, S.S.E. Recent Food Applications of Microbial Surfactants. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.; Ruiz, A.; Lanza, F.; Haange, S.-B.; Oberbach, A.; Till, H.; Bargiela, R.; Campoy, C.; Segura, M.T.; Richter, M.; et al. Microbiota from the Distal Guts of Lean and Obese Adolescents Exhibit Partial Functional Redundancy besides Clear Differences in Community Structure: Metaproteomic Insights Associated to Human Obesity. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Anzawa, D.; Takami, K.; Ishizuka, A.; Mawatari, T.; Kamikado, K.; Sugimura, H.; Nishijima, T. Effect of Bifidobacterium Animalis ssp. Lactis GCL2505 on Visceral Fat Accumulation in Healthy Japanese Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 2016, 35, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cerdó, T.; García-Santos, J.; Bermúdez, M.G.; Campoy, C. The Role of Probiotics and Prebiotics in the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity. Nutrients 2019, 11, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luoto, R.; Kalliomäki, M.; Laitinen, K.; Isolauri, E. The Impact of Perinatal Probiotic Intervention on the Development of Overweight and Obesity: Follow-up Study from Birth to 10 Years. Int. J. Obes. 2010, 34, 1531–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Takiishi, T.; Fenero, C.I.M.; Câmara, N.O.S. Intestinal Barrier and Gut Microbiota: Shaping Our Immune Responses throughout Life. Tissue Barriers 2017, 5, e1373208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.B.; Moubarac, J.-C.; Louzada, M.L.; Rauber, F.; Khandpur, N.; Cediel, G.; Neri, D.; Martinez-Steele, E.; et al. Ultra-Processed Foods: What They Are and How to Identify Them. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chassaing, B.; Koren, O.; Goodrich, J.K.; Poole, A.C.; Srinivasan, S.; Ley, R.E.; Gewirtz, A.T. Dietary Emulsifiers Impact the Mouse Gut Microbiota Promoting Colitis and Metabolic Syndrome. Nature 2015, 519, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Naimi, S.; Viennois, E.; Gewirtz, A.T.; Chassaing, B. Direct Impact of Commonly Used Dietary Emulsifiers on Human Gut Microbiota. Microbiome 2021, 9, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lock, J.Y.; Carlson, T.L.; Wang, C.-M.; Chen, A.; Carrier, R.L. Acute Exposure to Commonly Ingested Emulsifiers Alters Intestinal Mucus Structure and Transport Properties. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickerson, K.P.; Chanin, R.; McDonald, C. Deregulation of Intestinal Anti-Microbial Defense by the Dietary Additive, Maltodextrin. Gut Microbes 2015, 6, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miclotte, L.; De Paepe, K.; Rymenans, L.; Callewaert, C.; Raes, J.; Rajkovic, A.; Van Camp, J.; Van de Wiele, T. Dietary Emulsifiers Alter Composition and Activity of the Human Gut Microbiota in Vitro, Irrespective of Chemical or Natural Emulsifier Origin. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 577474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swidsinski, A.; Ung, V.; Sydora, B.C.; Loening-Baucke, V.; Doerffel, Y.; Verstraelen, H.; Fedorak, R.N. Bacterial Overgrowth and Inflammation of Small Intestine After Carboxymethylcellulose Ingestion in Genetically Susceptible Mice. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, S.; Shani Levi, C.; Fahoum, L.; Ungar, Y.; Meyron-Holtz, E.G.; Shpigelman, A.; Lesmes, U. Revisiting the Carrageenan Controversy: Do We Really Understand the Digestive Fate and Safety of Carrageenan in Our Foods? Food Funct. 2018, 9, 1344–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.-Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, H.-M.; Yan, X.-J. κ-Carrageenan Induces the Disruption of Intestinal Epithelial Caco-2 Monolayers by Promoting the Interaction between Intestinal Epithelial Cells and Immune Cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2013, 8, 1635–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chassaing, B.; Van de Wiele, T.; De Bodt, J.; Marzorati, M.; Gewirtz, A.T. Dietary Emulsifiers Directly Alter Human Microbiota Composition and Gene Expression Ex Vivo Potentiating Intestinal Inflammation. Gut 2017, 66, 1414–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-T.; Yuan, Y.-Z.; Feng, Q.-P.; Hu, M.-Y.; Li, W.-J.; Wu, X.; Xiang, S.-Y.; Yu, S.-Q. Food Emulsifier Polysorbate 80 Promotes the Intestinal Absorption of Mono-2-Ethylhexyl Phthalate by Disturbing Intestinal Barrier. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2021, 414, 115411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zangara, M.; Sangwan, N.; McDonald, C. Common food additives accelerate onset of inflammatory bowel disease in mice by altering microbiome composition and host-microbe interaction. Microbiome 2021, 160, s53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K. Food Additive P-80 Impacts Mouse Gut Microbiota Promoting Intestinal Inflammation, Obesity and Liver Dysfunction. SOJMID 2016, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Feng, F. Antimicrobial Emulsifier-Glycerol Monolaurate Induces Metabolic Syndrome, Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis, and Systemic Low-Grade Inflammation in Low-Fat Diet Fed Mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, 1700547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Q.; Fu, A.; Deng, L.; Zhao, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Feng, F. High-Dose Glycerol Monolaurate Up-Regulated Beneficial Indigenous Microbiota without Inducing Metabolic Dysfunction and Systemic Inflammation: New Insights into Its Antimicrobial Potential. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fortuoso, B.F.; dos Reis, J.H.; Gebert, R.R.; Barreta, M.; Griss, L.G.; Casagrande, R.A.; de Cristo, T.G.; Santiani, F.; Campigotto, G.; Rampazzo, L.; et al. Glycerol Monolaurate in the Diet of Broiler Chickens Replacing Conventional Antimicrobials: Impact on Health, Performance and Meat Quality. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 129, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Chen, G.; Cao, G.; Tang, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, B.; Yang, C. Effects of α-Glyceryl Monolaurate on Growth, Immune Function, Volatile Fatty Acids, and Gut Microbiota in Broiler Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 100875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, A.E.; Crawford, M.; Jasbi, P.; Fessler, S.; Sweazea, K.L. Lipopolysaccharide and the Gut Microbiota: Considering Structural Variation. FEBS Lett. 2022, 596, 849–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Lai, H.; Zou, L.; Yin, S.; Wang, C.; Han, X.; Xia, X.; Hu, K.; He, L.; Zhou, K.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance and Resistance Genes in Salmonella Strains Isolated from Broiler Chickens along the Slaughtering Process in China. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 259, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassaing, B.; Compher, C.; Bonhomme, B.; Liu, Q.; Tian, Y.; Walters, W.; Nessel, L.; Delaroque, C.; Hao, F.; Gershuni, V.; et al. Randomized Controlled-Feeding Study of Dietary Emulsifier Carboxymethylcellulose Reveals Detrimental Impacts on the Gut Microbiota and Metabolome. Gastroenterology 2021, 162, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vors, C.; Drai, J.; Pineau, G.; Laville, M.; Vidal, H.; Laugerette, F.; Michalski, M.-C. Emulsifying Dietary Fat Modulates Postprandial Endotoxemia Associated with Chylomicronemia in Obese Men: A Pilot Randomized Crossover Study. Lipids Health Dis. 2017, 16, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pussinen, P.J.; Havulinna, A.S.; Lehto, M.; Sundvall, J.; Salomaa, V. Endotoxemia Is Associated With an Increased Risk of Incident Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ivancovsky-Wajcman, D.; Fliss-Isakov, N.; Webb, M.; Bentov, I.; Shibolet, O.; Kariv, R.; Zelber-Sagi, S. Ultra-processed Food Is Associated with Features of Metabolic Syndrome and Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Liver Int. 2021, 41, 2635–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Cai, H.; Jiang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhong, H.; Zhang, H.; Feng, F. Glycerol-Monolaurate-Mediated Attenuation of Metabolic Syndrome Is Associated with the Modulation of Gut Microbiota in High-Fat-Diet-Fed Mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, 1801417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, J.; Da Silva, A.S.; Fortuoso, B.F.; Reis, J.H.; Gebert, R.R.; Griss, L.G.; Boiago, M.M.; Lopes, L.Q.S.; Santos, R.C.V.; Wagner, R.; et al. Chemical Composition, Lipid Peroxidation, and Fatty Acid Profile in Meat of Broilers Fed with Glycerol Monolaurate Additive. Food Chem. 2020, 330, 127187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Yang, K.; Wang, Y.; Dai, X. Anti-Aging Effect of Agar Oligosaccharide on Male Drosophila Melanogaster and Its Preliminary Mechanism. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Dai, X. Agar Oligosaccharides Ameliorate the Intestinal Inflammation of Male Drosophila Melanogaster via Modulating the Microbiota, and Immune and Cell Autophagy. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 1202–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawi, M.H.; Abdullah, A.; Ismail, A.; Sarbini, S.R. Manipulation of Gut Microbiota Using Acacia Gum Polysaccharide. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 17782–17797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimidis, K.; Bryden, K.; Chen, X.; Papachristou, E.; Verney, A.; Roig, M.; Hansen, R.; Nichols, B.; Papadopoulou, R.; Parrett, A. The Impact of Food Additives, Artificial Sweeteners and Domestic Hygiene Products on the Human Gut Microbiome and Its Fibre Fermentation Capacity. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 3213–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robert, C.; Buisson, C.; Laugerette, F.; Abrous, H.; Rainteau, D.; Humbert, L.; Vande Weghe, J.; Meugnier, E.; Loizon, E.; Caillet, F.; et al. Impact of Rapeseed and Soy Lecithin on Postprandial Lipid Metabolism, Bile Acid Profile, and Gut Bacteria in Mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2021, 65, 2001068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caenepeel, C.; Sadat Seyed Tabib, N.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Vermeire, S. Review Article: How the Intestinal Microbiota May Reflect Disease Activity and Influence Therapeutic Outcome in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Acc. Perspect 2020, 52, 1453–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, E.M.; Juul, F.; Neri, D.; Rauber, F.; Monteiro, C.A. Dietary share of ultra-processed foods and metabolic syndrome in the US adult population. Prev. Med. 2019, 125, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Emulsifier Name | E-Number | Origin | Foods | ADI (per kg of Body Weight per Day) | Effects on Gut Microbiota and Metabolic Health | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Studies | Animal Studies | Human Studies | |||||

| Agar Agar | E406 | Natural | Jelly, bakery, confectionery, dairy products, beverage, meat products | No ADI | ↓ Clostridiales (Faecalibacterium genus) ↓ Verrucomicrobiales [65] | ↓ Klebsiella [90] ↑ Gluconobacter [89] -antiaging -anti-inflammatory [89] | |

| Carboxymethylcellulose | E466 | Artificial | Desserts, snacks, edible ices, chewing gums, vegetable oil, breakfast cereals, food supplements, creams, milk products, dried fruit, nut butter, chocolate products, bread and rolls, processed cheese, sauces, soups, meat products | No ADI Maximum use levels (per kg body weight per day): 660−900 mg | ↓ Microbiota diversity indices [68] Changes in mucus barrier [68] Altered microbiota gene expression with increased bioactive flagellin levels [64] | Modify microbiota diversity ↑ Proteobacteria ↑ Escherichia coli ↓ Bacteroides ↓ Clostridia ↑ LPS levels ↑ flagellin expression ↑ Increased pro-inflammatory potential | ↓ Microbiota richness ↓ Microbiota diversity ↓ Faecalibacterium prausnitzii [82] ↓ Ruminococcus spp. ↑ Roseburia spp. and Lachnospiraceae [82] No variations in fecal levels of LPS and flagellin [82] |

| Carrageenan | E407 | Natural | Dairy products, chocolate milk, ice cream, cottage cheese, sour cream, processed meats, mayonnaise, infant formulas, almond milk, processed meats, soy-based products, vegan and vegetarian products | 75 mg | ↑ LPS levels [66] ↑ flagellin expression [65] | ↓ Clostridiales (Faecalibacterium genus) ↓ Verrucomicrobiales [66] | Disrupt the intercellular junctions acting on actin filament and the zonula occludens-1 [Z0-1] proteins between intestinal cells [71] |

| Glycerol monolaurate | E471 | Natural | Processed cakes, bread, and ice creams | No ADI | Induced body weight gain [76] Impact lipid metabolism improving metabolic syndrome in HFD [94] ↓ LPS in high-fat mice [78] Worsen lipid metabolism in LFD [78] ↓ Akkermansia, Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus [76] ↑ Escherichia coli, Lactococcus, and Flexispira [76] | ||

| Gums | E414 acacia gum E412 guar gum E415 xanthan gum | Natural | Ice creams, yogurt, salad dressing, gluten-free baked goods, sauces, and breakfast cereals | No ADI | Acacia gum: -significantly promotes Bifidobacteria proliferation—inhibits the Clostridium histolyticum group [90] -decrease gut dysbiosis, -↑ SCFA production, especially butyrate [90] | ||

| Lecithins | E322 | Natural | Cocoa and chocolate products, margarine, biscuits and pastries, confectionery, baby food | No ADI | ↑ Clostridium leptum (butyrate production bacteria) Anti-inflammatory effects [92] | ||

| Maltodextrin | - | Artificial | Cooked cereals, rice, meat substitutes, bakery foods, salad dressings, frozen meals, soups, sweets, energy, and sports drinks | No ADI | ↑ Bifidobacterium [91] | ||

| Polysorbate 80 | E433 | Artificial | Ice creams, whipped toppings, and other frozen desserts | 25 mg | ↓ Clostridiales (Faecalibacterium genus) ↓ Verrucomicrobiales ↓ Microbiota diversity indices [68] Changes in mucus barrier [68] | ↓ microbiota diversity, increasing Proteobacteria and Escherichia coli levels and reducing Bacteroides and Clostridia [64] ↑ LPS levels ↑ flagellin expression [64] Microbiota encroachment, altered species composition, increased pro-inflammatory potential [69] | Altered glycemic tolerance, hyperinsulinemia, increased levels of liver enzymes as alkaline phosphatase (ALP), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) [75] ↑ body weight [75] ↑ adipose tissue [75] |

| Propylene glycol alginate | E405 | Artificial | Dried soups, salad dressings, cakes, muffins, biscuits, cupcakes, powdered drink mixes, soft and alcoholic drinks | 55 mg | |||

| Rhamnolipids and Sophorolipids | - | Natural | Bread, hamburgers, baguettes, pizza, croissants, salad dressing, bread, cakes, biscuits, and ice creams | No ADI | ↑ pathogenic Escherichia/Shigella and Fusobacterium ↓ Bacteroidetes [68] ↑ flagellar assembly and general motility [68] ↓ SFCAs production (especially butyrate and propionate) [68] | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Siena, M.; Raoul, P.; Costantini, L.; Scarpellini, E.; Cintoni, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Rinninella, E.; Mele, M.C. Food Emulsifiers and Metabolic Syndrome: The Role of the Gut Microbiota. Foods 2022, 11, 2205. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11152205

De Siena M, Raoul P, Costantini L, Scarpellini E, Cintoni M, Gasbarrini A, Rinninella E, Mele MC. Food Emulsifiers and Metabolic Syndrome: The Role of the Gut Microbiota. Foods. 2022; 11(15):2205. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11152205

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Siena, Martina, Pauline Raoul, Lara Costantini, Emidio Scarpellini, Marco Cintoni, Antonio Gasbarrini, Emanuele Rinninella, and Maria Cristina Mele. 2022. "Food Emulsifiers and Metabolic Syndrome: The Role of the Gut Microbiota" Foods 11, no. 15: 2205. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11152205

APA StyleDe Siena, M., Raoul, P., Costantini, L., Scarpellini, E., Cintoni, M., Gasbarrini, A., Rinninella, E., & Mele, M. C. (2022). Food Emulsifiers and Metabolic Syndrome: The Role of the Gut Microbiota. Foods, 11(15), 2205. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11152205