Antimicrobial Resistance, Biocide Tolerance, and Bacterial Diversity of a Dressing Made from Coriander and Parsley after Application of Treatments Using High Hydrostatic Pressure Alone or in Combination with Moderate Heat

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Dressing Samples

2.2. High-Hydrostatic Pressure Treatments

2.3. Microbiological Analysis

2.4. Identification of Bacterial Isolates

2.5. Determination of Biocide Tolerance

2.6. Antimicrobial Resistance Testing

2.7. DNA Extraction from Samples

2.8. DNA Sequencing and Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Influence of Pressure Treatments and Storage Time on pH, Microbial Load, and Antimicrobial-Resistant Populations

3.2. Identification of Bacterial Isolates

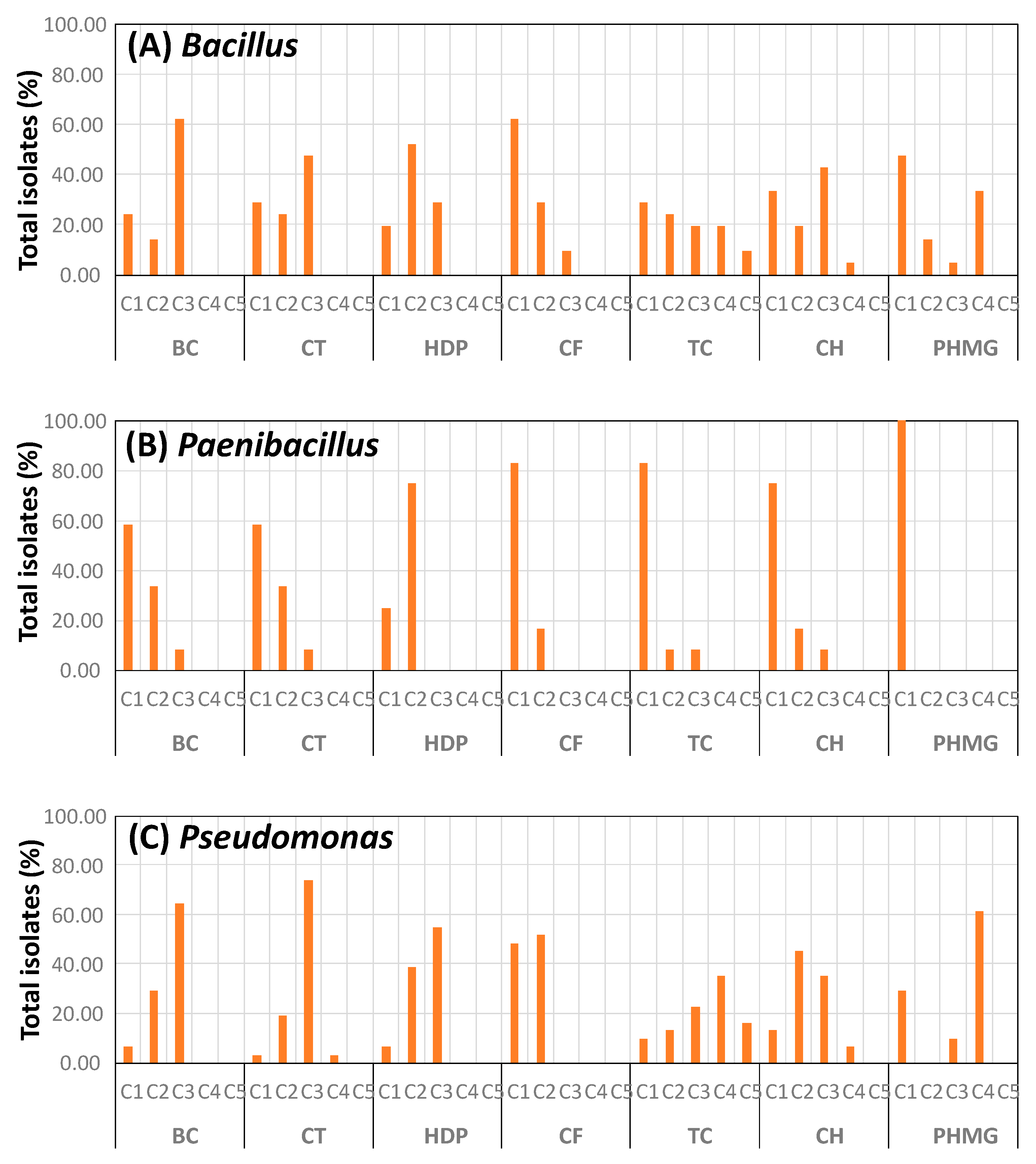

3.3. Biocide Tolerance of Isolates

3.4. Antimicrobial Resistance of Pseudomonas Isolates

3.5. Effect of Treatments on the Bacterial Diversity of Samples

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Slavin, J.L.; Lloyd, B. Health benefits of fruits and vegetables. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blekkenhorst, L.; Sim, M.; Bondonno, C.; Bondonno, N.; Ward, N.; Prince, R.; Devine, A.; Lewis, J.; Hodgson, J. Cardiovascular health benefits of specific vegetable types: A narrative review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeing, H.; Bechthold, A.; Bub, A.; Ellinger, S.; Haller, D.; Kroke, A.; Leschik-Bonnet, E.; Müller, M.J.; Oberritter, H.; Schulze, M.; et al. Critical review: Vegetables and fruit in the prevention of chronic diseases. Eur. J. Nutr. 2012, 51, 637–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadjilouka, A.; Tsaltas, D. Cyclospora cayetanensis—Major outbreaks from ready to eat fresh fruits and vegetables. Foods 2020, 9, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.T.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wan, S.W.; Hao, J.J.; Jiang, R.D.; Song, F.J. Characteristics of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in ready-to-eat vegetables in China. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Jang, H.; Matthews, K.R. Effect of the food production chain from farm practices to vegetable processing on outbreak incidence. Microb. Biotechnol. 2014, 7, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuchat, L.R. Ecological factors influencing survival and growth of human pathogens on raw fruits and vegetables. Microbes Infect. 2002, 4, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critzer, F.J.; Doyle, M.P. Microbial ecology of foodborne pathogens associated with produce. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2010, 21, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplitski, M.; Warriner, K.; Bartz, J.; Schneider, K.R. Untangling metabolic and communication networks: Interactions of enterics with phytobacteria and their implications in produce safety. Trends Microbiol. 2011, 19, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelzer, K.; Pouillot, R.; Egan, K.; Dennis, S. Produce consumption in the United States: An analysis of consumption frequencies, serving sizes, processing forms, and high-consuming population subgroups for microbial risk assessments. J. Food. Prot. 2012, 75, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschape, H.; Prager, R.; Streckel, W.; Fruth, A.; Tietze, E.; Böhme, G. Verotoxinogenic Citrobacter freundii associated with severe gastroenteritis and cases of haemolytic uraemic syndrome in a nursery school: Green butter as the infection source. Epidemiol. Infect. 1995, 114, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naimi, T.S.; Wicklund, J.H.; Olsen, S.J.; Krause, G.; Wells, J.G.; Bartkus, J.M.; Boxrud, D.J.; Sullivan, M.; Kassenborg, H.; Besser, J.M.; et al. Concurrent outbreaks of Shigella sonnei and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infections associated with parsley: Implications for surveillance and control of foodborne illness. J. Food. Prot. 2003, 66, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreaks of Shigella sonnei infection associated with eating fresh parsley—United States and Canada, July–August 1998. 1999. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00056895.htm (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Chan, Y.C.; Blaschek, H.P. Comparative analysis of Shigella boydii 18 foodborne outbreak isolate and related enteric bacteria: Role of rpoS and adiA in acid stress response. J. Food. Prot. 2005, 68, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA, Food and Drug Administration. Microbiological Surveillance Sampling: FY18-21 Fresh Herbs (Cilantro, Basil & Parsley) Assignment. 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/sampling-protect-food-supply/microbiological-surveillance-sampling-fy18-21-fresh-herbs-cilantro-basil-parsley-assignment (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Beach, C.; Cilantro Identified as Possible Source Behind Mystery Salmonella Oranienburg Outbreak. Food Safety News 2021. Available online: https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2021/09/cilantro-identified-as-possible-source-behind-mystery-salmonella-oranienburg-outbreak/ (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- FDA, Food and Drug Administration. FDA Sampling Fresh Herbs, Guacamole and Processed Avocado. 2021. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/cfsan-constituent-updates/fda-sampling-fresh-herbs-guacamole-and-processed-avocado (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Finger, J.A.F.F.; Maffei, D.F.; Dias, M.; Mendes, M.A.; Pinto, U.M. Microbiological quality and safety of minimally processed parsley (Petroselinum crispum) sold in food markets, southeastern Brazil. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 131, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbowska, M.; Berthold-Pluta, A.; Stasiak-Różańska, L. Microbiological quality of selected spices and herbs including the presence of Cronobacter spp. Food Microbiol. 2015, 49, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande Burgos, M.J.; López Aguayo, M.; Pérez Pulido, R.; Galvez, A.; Lucas, R. Analysis of the microbiota of refrigerated chopped parsley after treatments with a coating containing enterocin AS-48 or by high-hydrostatic pressure. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99 Pt 1, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Feng, H.; Luo, Y. Microbial reduction and storage quality of fresh-cut cilantro washed with acidic electrolyzed water and aqueous ozone. Food Res. Int. 2004, 37, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allende, A.; McEvoy, J.; Tao, Y.; Luo, Y. Antimicrobial effect of acidified sodium chlorite, sodium chlorite, sodium hypochlorite, and citric acid on Escherichia coli O157:H7 and natural microflora of fresh-cut cilantro. Food Control 2009, 20, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Fang, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Q.F.; Jin, T.Z. Effect of alternatives to chlorine washing for sanitizing fresh coriander. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Hsu, W.Y.; Huang, T.S.; Simonne, A. Evaluation of the microbiological quality of fresh cilantro, green onions, and hot peppers from different types of markets in three U.S. States. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, K.; Bettermann, A.; Jechalke, S.; Fornefeld, E.; Vanrobaeys, Y.; Stalder, T.; Top, E.M.; Smalla, K. The transferable resistome of produce. mBio 2018, 9, e01300-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramaniam, V.B.; Martínez-Monteagudo, S.I.; Gupta, R. Principles and application of high pressure–based technologies in the food industry. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 6, 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Considine, K.M.; Kelly, A.L.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Hill, C.; Sleator, R.D. High-pressure processing and effects on microbial food safety and food quality. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 281, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbo, M.R.; Bevilacqua, A.; Campaniello, D.; D’Amato, D.; Speranza, B.; Sinigaglia, M. Prolonging microbial shelf life of foods through the use of natural compounds and non-thermal approaches—A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 44, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendueles, E.; Omer, M.; Alvseike, O.; Alonso-Calleja, C.; Capita, R.; Prieto, M. Microbiological food safety assessment of high hydrostatic pressure processing: A review. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georget, E.; Sevenich, R.; Reineke, K.; Mathys, A.; Heinz, V.; Callanan, M.; Rauh, C.; Knorr, D. Inactivation of microorganisms by high isostatic pressure processing in complex matrices: A review. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2015, 27, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aganovic, K.; Hertel, C.; Vogel, R.F.; Johne, R.; Schlüter, O.; Schwarzenbolz, U.; Jäger, H.; Holzhauser, T.; Bergmair, J.; Roth, A.; et al. Aspects of high hydrostatic pressure food processing: Perspectives on technology and food safety. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 3225–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evelyn; Silva, F.V. Heat assisted HPP for the inactivation of bacteria, moulds and yeasts spores in foods: Log reductions and mathematical models. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzecka, U.; Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W.; Zakrzewski, A.; Zadernowska, A.; Fraqueza, M.J. High pressure processing, acidic and osmotic stress increased resistance to aminoglycosides and tetracyclines and the frequency of gene transfer among strains from commercial starter and protective cultures. Food Microbiol. 2022, 107, 104090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez López, J.; Grande, M.J.; Pérez-Pulido, R.; Gálvez, A.; Lucas, R. Impact of high-hydrostatic pressure treatments applied singly or in combination with moderate heat on the microbial load, antimicrobial resistance, and bacterial diversity of guacamole. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics; Stackebrandt, E., Goodfellow, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 115–148. [Google Scholar]

- Grande Burgos, M.J.; Fernández Márquez, M.L.; Pérez Pulido, R.; Gálvez, A.; Lucas López, R. Virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli strains isolated from hen egg shells. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 238, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 30th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nocker, A.; Sossa-Fernandez, P.; Burr, M.D.; Camper, A.K. Use of propidium monoazide for live/dead distinction in microbial ecology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 5111–5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elizaquível, P.; Sánchez, G.; Aznar, R. Quantitative detection of viable foodborne E. coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella in fresh-cut vegetables combining propidium monoazide and real-time PCR. Food Control 2012, 25, 704–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glöckner, F.O. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmieder, R.; Edwards, R. Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 863–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Lozupone, C.A.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Fierer, N.; Knight, R. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108 (Suppl. 1), 4516–4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reva, O.N.; Smirnov, V.V.; Pettersson, B.; Priest, F.G. Bacillus endophyticus sp. nov., isolated from the inner tissues of cotton plants (Gossypium sp.). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.J. An β-1,4-Xylanase with exo-enzyme activity produced by Paenibacillus xylanilyticus KJ-03 and its cloning and characterization. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 23, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martín, M.F.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V.; Swanson, B.G. Food processing by high hydrostatic pressure. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2002, 42, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsetti, A.; Settanni, L.; Chaves López, C.; Felis, G.E.; Mastrangelo, M.; Suzzi, G. A taxonomic survey of lactic acid bacteria isolated from wheat (Triticum durum) kernels and non-conventional flours. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 30, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Neubeck, M.; Baur, C.; Krewinkel, M.; Stoeckel, M.; Kranz, B.; Stressler, T.; Fischer, L.; Hinrichs, J.; Scherer, S.; Wenning, M. Biodiversity of refrigerated raw milk microbiota and their enzymatic spoilage potential. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 211, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez Pulido, R.; Toledo, J.; Grande, M.J.; Gálvez, A.; Lucas, R. Analysis of the effect of high hydrostatic pressure treatment and enterocin AS-48 addition on the bacterial communities of cherimoya pulp. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 196, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total Aerobic Mesophiles | T0 | T2 | T5 | T10 | T20 |

| Controls | 5.49 ± 0.15 | 6.13 ± 0.12 a | 6.49 ± 0.04 a | 6.57 ± 0.15 a | 6.50 ± 0.16 a |

| Treatment A | 1.30 ± 0.14 b | 1.65 ± 0.21 b,d | 1.30 ± 0.04 b | 1.84 ± 0.43 b | 1.54 ± 0.10 b |

| Treatment B | 1.02 ± 0.07 b | 1.39 ± 0.13 b | 1.30 ± 0.15 b | 1.30 ± 0.11 b | < 1.00 |

| Treatment C | 1.02 ± 0.02 b | 1.17 ± 0.03 b | 1.17 ± 0.15 b | 1.74± 0.24 b,c,d | 1.77 ± 0.20 b,c,d |

| Treatment D | 1.30 ± 0.22 b | 1.54 ± 0.14 b | <1.00 | 1.17 ± 0.17 b | <1.00 |

| Enterobacteriaceae | T0 | T2 | T5 | T10 | T20 |

| Controls | 5.50 ± 0.07 e | 5.78 ± 0.23 e | 5.55 ± 0.22 e | 6.25 ± 0.19 f | 6.04 ± 0.11 |

| Treatment A | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 |

| Treatment B | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 |

| Treatment C | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 |

| Treatment D | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 |

| Yeasts and Molds | T0 | T2 | T5 | T10 | T20 |

| Controls | 5.19 ± 0.27 | 5.54 ± 0.10 h | 5.17 ± 0.13 h | 4.32 ± 0.20 g,h | 5.49 ± 0.05 h |

| Treatment A | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 |

| Treatment B | 1.01 ± 0.02 b | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 |

| Treatment C | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 |

| Treatment D | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 | <1.00 |

| pH | T0 | T2 | T5 | T10 | T20 |

| Controls | 5.06 ± 0.05 | 4.89 ± 0.05 | 4.85 ± 0.07 | 4.66 ± 0.05 i | 5.53 ± 0.11 j |

| Treatment A | 5.09 ± 0.08 | 4.94 ± 0.04 | 5.00 ± 0.07 | 4.94 ± 0.08 | 5.01 ± 0.05 |

| Treatment B | 4.98 ± 0.02 | 5.11 ± 0.08 | 4.95 ± 0.07 | 4.96 ± 0.05 | 4.95 ± 0.08 |

| Treatment C | 5.02 ±0. 02 | 5.03 ± 0.05 | 5.01 ± 0.04 | 5.02 ± 0.01 | 5.01 ± 0.00 |

| Treatment D | 4.99 ± 0.01 | 4.97 ± 0.05 | 4.98 ± 0.01 | 4.98 ± 0.02 | 4.94 ± 0.02 |

| Antimicrobial | T0 | T2 | T5 | T10 | T20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cefotaxime | 2.57 ± 0.18 a | 3.76 ± 0.33 a | 3.26 ± 0.09 a | 3.70 ± 0.25 a | <1.00 |

| Imipenem | 4.47 ± 0.09 a,c | 5.15 ± 0.15 b,c | 5.17 ± 0.19 b,c | 5.12 ± 0.11 b,c | 3.07 ± 0.12 a |

| KPC aerobiosis | 5.11 ± 0.10 c | 5.20 ± 0.05 c | 5.05 ± 0.12 c | 4.81 ± 0.22 c | 2.88 ± 0.06 |

| KPC anaerobiosis | <1.00 | 2.39 ± 0.13 d | 2.34 ± 0.03 d | 3.56 ± 0.18 d | <1.00 |

| Benzalkonium chloride | <1.00 | 1.02 ± 0.02 | 2.32 ± 0.21 | <1.00 | <1.00 |

| Genera (nº Isolates; %) | Species | Nº Isolates |

|---|---|---|

| Aerococcus (n = 1; 1.25%) | A. viridans | 1 |

| Bacillus (n = 21; 26.25%) | B. endophyticus | 14 |

| B. filamentosus | 1 | |

| B. oceanisediminis | 2 | |

| B. safensis | 1 | |

| B. simplex | 2 | |

| B. zhangzhouensis | 1 | |

| Lactobacillus (n = 10; 12.50%) | L. curvatus | 1 |

| L. graminis | 9 | |

| Obesumbacterium (n = 2; 2.50%) | O. proteus | 2 |

| Paenibacillus (n = 12; 15.00%) | P. illinoiensis | 1 |

| P. taichungensis | 1 | |

| P. tundrae | 1 | |

| P. xylanexedens | 1 | |

| P. xylanilyticus | 8 | |

| Pseudomonas (n = 31; 38.75%) | P. koreensis | 1 |

| P. lactis | 10 | |

| P. lurida | 1 | |

| P. paralactis | 18 | |

| P. trivialis | 1 | |

| Rahnella (n = 1; 1.25%) | R. aquatilis | 1 |

| Siccibacter (n = 1; 1.25%) | S. turicensis | 1 |

| Staphylococcus (n = 1; 1.25%) | S. capitis | 1 |

| Isolate | Day | Species | Antimicrobial Resistance * |

|---|---|---|---|

| CI21 | 5 | P. koreensis | AMC, FOX, CTX, C, K, E |

| K25 | 10 | P. lactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, MEM, E |

| CF3 | 0 | P. lactis | AMC, CAZ, FOX, CTX, S3, E |

| CF19 | 5 | P. lactis | FOX, CTX, E |

| CF24 | 5 | P. lactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, C, E |

| CF28 | 10 | P. lactis | AMC, CAZ, FOX, CTX, C, E |

| CF30 | 10 | P. lactis | AMC, CAZ, FOX, CTX, C, E |

| CF34 | 10 | P. lactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, C |

| CI19 | 5 | P. lactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, S3 |

| CI25 | 10 | P. lactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, C, E |

| CI26 | 10 | P. lactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, MEM, K, E |

| CI33 | 10 | P. lurida | AMC, CAZ, FOX, CTX |

| CBA3 | 5 | P. paralactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, K, E |

| K9 | 2 | P. paralactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, MEM, K, E |

| K14 | 2 | P. paralactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, K, E |

| K19 | 5 | P. paralactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, K, E |

| K36 | 20 | P. paralactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, K, E |

| K44 | 20 | P. paralactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, MEM, C, E |

| CF9 | 2 | P. paralactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, MEM, E |

| CF11 | 2 | P. paralactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, E |

| CF13 | 2 | P. paralactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, MEM, C, E |

| CF15 | 2 | P. paralactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, MEM, E |

| CF20 | 5 | P. paralactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, MEM, E |

| CI2 | 0 | P. paralactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, MEM, K, E |

| CI6 | 0 | P. paralactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, K |

| CI10 | 2 | P. paralactis | AMC, CAZ, FOX, CTX, K, S3, E |

| CI15 | 2 | P. paralactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, K, E |

| CI18 | 5 | P. paralactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, K, E |

| CI20 | 5 | P. paralactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, K, E |

| CI28 | 10 | P. paralactis | AMC, FOX, CTX, MEM, E |

| CI5 | 0 | P. trivialis | AMC, CAZ, FOX, CTX, E |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez López, J.; Grande Burgos, M.J.; Pérez Pulido, R.; Iglesias Valenzuela, B.; Gálvez, A.; Lucas, R. Antimicrobial Resistance, Biocide Tolerance, and Bacterial Diversity of a Dressing Made from Coriander and Parsley after Application of Treatments Using High Hydrostatic Pressure Alone or in Combination with Moderate Heat. Foods 2022, 11, 2603. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11172603

Rodríguez López J, Grande Burgos MJ, Pérez Pulido R, Iglesias Valenzuela B, Gálvez A, Lucas R. Antimicrobial Resistance, Biocide Tolerance, and Bacterial Diversity of a Dressing Made from Coriander and Parsley after Application of Treatments Using High Hydrostatic Pressure Alone or in Combination with Moderate Heat. Foods. 2022; 11(17):2603. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11172603

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez López, Javier, Maria José Grande Burgos, Rubén Pérez Pulido, Belén Iglesias Valenzuela, Antonio Gálvez, and Rosario Lucas. 2022. "Antimicrobial Resistance, Biocide Tolerance, and Bacterial Diversity of a Dressing Made from Coriander and Parsley after Application of Treatments Using High Hydrostatic Pressure Alone or in Combination with Moderate Heat" Foods 11, no. 17: 2603. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11172603

APA StyleRodríguez López, J., Grande Burgos, M. J., Pérez Pulido, R., Iglesias Valenzuela, B., Gálvez, A., & Lucas, R. (2022). Antimicrobial Resistance, Biocide Tolerance, and Bacterial Diversity of a Dressing Made from Coriander and Parsley after Application of Treatments Using High Hydrostatic Pressure Alone or in Combination with Moderate Heat. Foods, 11(17), 2603. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11172603