Social Norms Support the Protein Transition: The Relevance of Social Norms to Explain Increased Acceptance of Alternative Protein Burgers over 5 Years

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

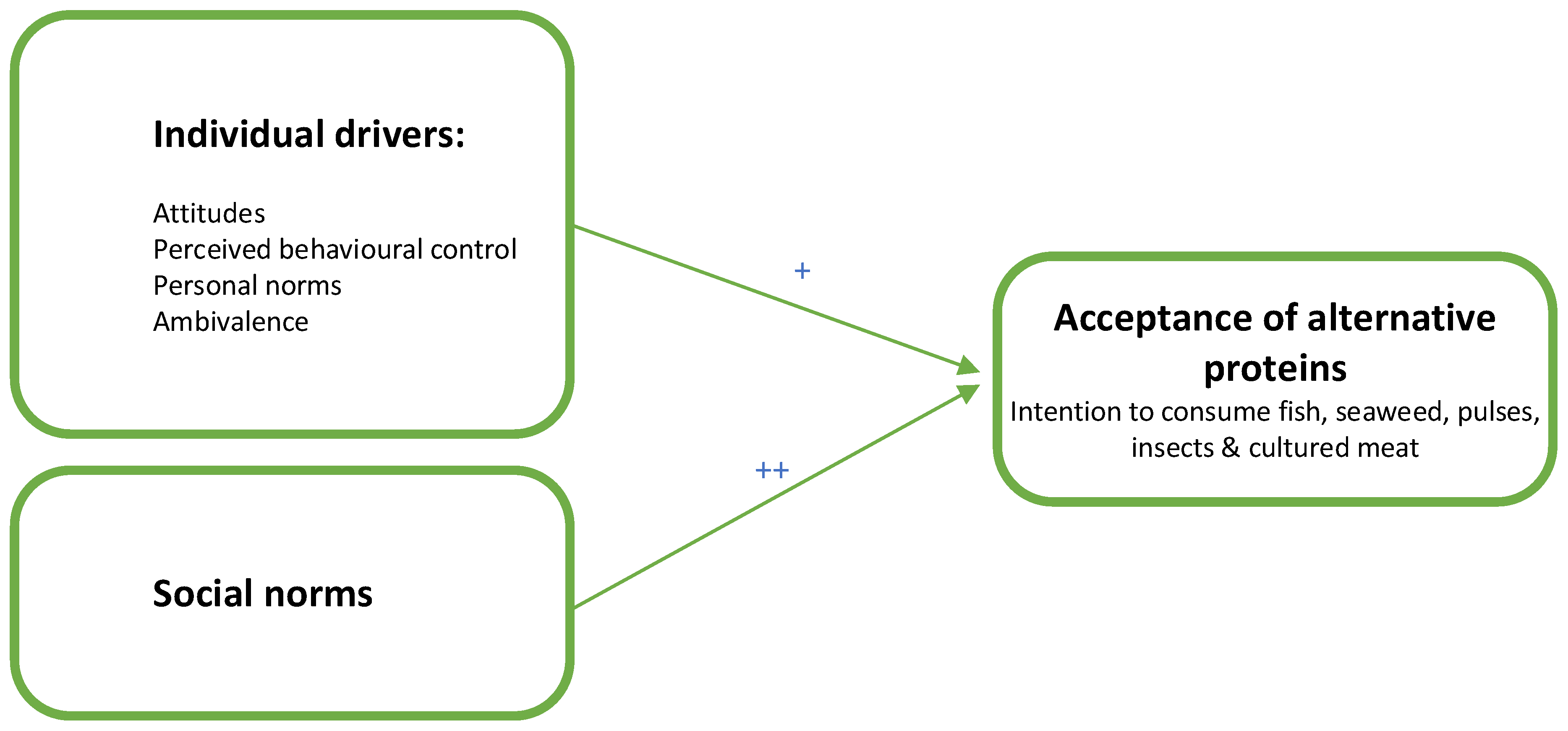

2.1. Explanatory Value of Social Norms beyond Individual Drivers in Accepting Alternative Proteins

2.2. Social Norms and Their Predictive Value Regarding Accepting Alternative Proteins over Time

2.3. Social Norms across Consumer Groups Varying in Dietary Consumption of Meat

3. Method

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Data

3.3. Participants

3.4. Measurements

4. Results

4.1. Sample Description: Perceptions and Intentions over Time

4.2. Explanatory Value of Social Norms beyond a Set of Individual Drivers on Intention to Consume Alternative Protein Burgers (Cross-Sectional Data)

4.3. Relevant Drivers to Explain Variation in Intentions over the Years (2019–2015)

4.4. Variation across Groups: Meat Lovers, Flexitarians, Meat Abstainers

5. General Discussion

5.1. The Strength of Social Norms

5.2. Social Norms Accelerate the Protein Transition over Time

5.3. Social Bubbles: Variations in Explanatory Value of Social Norms across Dietary Groups

5.4. Limitations Resulting in Directions for Future Research

5.5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Fish | Seaweed | Pulses | Insects | In Vitro | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Year | 0.032 | 0.686 | 0.010 | 0.213 | −0.071 | −1.376 | 0.001 | 0.014 | 0.026 | 0.580 |

| Social norm | 0.573 *** | 11.805 | 0.588 *** | 11.748 | 0.518 *** | 9.444 | 0.477 *** | 7.363 | 0.465 *** | 8.546 |

| Attitude | 0.315 *** | 4.747 | 0.084 | 1.024 | 0.286 *** | 3.724 | 0.215 * | 2.451 | 0.176 * | 2.286 |

| PBC | 0.121 * | 2.373 | 0.088 | 1.681 | 0.059 | 1.007 | 0.193 ** | 2.903 | 0.228 *** | 3.932 |

| PN health | −0.056 | −0.976 | 0.020 | 0.312 | 0.187 ** | 2.840 | −0.019 | −0.244 | −0.055 | −0.785 |

| PN environment | −0.002 | −0.037 | −0.043 | −0.631 | −0.177 ** | −2.635 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.046 | 0.657 |

| Ambivalence | 0.016 | 0.237 | 0.189 * | 2.509 | 0.005 | 0.062 | 0.004 | 0.052 | 0.084 | 1.211 |

| F = (df1, df2); R2 | F(7, 213) = 37.652 ***; R2 = 0.561 *** | F(7, 213) = 41.239 ***; R2 = 0.584 *** | F(7, 204) = 25.734 ***; R2 = 0.478 *** | F(7, 164) = 2.183 ***; R2 = 0.474 *** | F(7, 199) = 46.423 ***; R2 = 0.615 *** | |||||

- Year showed no significant association with intention beyond the range of drivers.

- Social norms were again shown to be the most prominent driver of intentions beyond all individual drivers and years.

- Attitudes were also shown to be relevant to the intention to buy fish, pulses, insects, and in vitro meat.

- Perceived behavioural control was associated with fish, insects, and cultured meat.

- Personal norms were associated with pulses.

References

- Cocking, C.; Walton, J.; Kehoe, L.; Cashman, K.D.; Flynn, A. The role of meat in the European diet: Current state of knowledge on dietary recommendations, intakes and contribution to energy and nutrient intakes and status. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2020, 33, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagevos, H.; Verbeke, W. Meat consumption and flexitarianism in the Low Countries. Meat Sci. 2022, 192, 108894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RIVM. Dutch National Food Consumption Survey. 2022. Available online: https://www.rivm.nl/voedselconsumptiepeiling (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Verain, M.C.D.; Dagevos, H.; Jaspers, P. Flexitarianism in the Netherlands in the 2010 decade: Shifts, consumer segments and motives. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 96, 104445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlasca, M.C.; Qaim, M. Meat consumption and sustainability. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2022, 14, 6.1–6.25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiking, H.; de Boer, J. The next protein transition. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 105, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Consumer perception and behaviour regarding sustainable protein consumption: A systematic review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 61, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Weele, C.; Feindt, P.; van der Goot, A.J.; van Mierlo, B.; van Boekel, M. Meat alternatives: An integrative comparison. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoppa, V. Social pressure in the stadiums: Do agents change behavior without crowd support? J. Econ. Psychol. 2021, 82, 102344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, S. Social norms and their influence on eating behaviours. Appetite 2015, 86, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, I.; Shimul, A.S.; Liang, J.; Phau, I. Drivers and barriers toward reducing meat consumption. Appetite 2020, 149, 104636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Buckland, N.J. Perceptions about meat reducers: Results from two UK studies exploring personality impressions and perceived group membership. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 93, 104289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Bouwman, E.P.; Reinders, M.J.; Dagevos, H. A systematic review on consumer acceptance of alternative proteins: Pulses, algae, insects, plant-based meat alternatives, and cultured meat. Appetite 2021, 159, 105058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Verain, M.C.D.; Dagevos, H. Positive emotions explain increased intention to consume five types of alternative proteins. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 96, 104446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüttel, S.; Leuchten, M.T.; Leyer, M. The importance of social norm on adopting sustainable digital fertilisation methods. Organ. Environ. 2020, 35, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronteltap, A.; Van Trijp, J.C.M.; Renes, R.J.; Frewer, L.J. Consumer acceptance of technology-based food innovations: Lessons for the future of nutrigenomics. Appetite 2007, 49, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menozzi, D.; Sogari, G.; Veneziani, M.; Simoni, E.; Mora, C. Eating novel foods: An application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to predict the consumption of an insect-based product. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 59, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Van den Puttelaar, J.; Verain, M.C.D.; Veldkamp, T. Consumer acceptance of insects as food and feed: The relevance of affective factors. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 77, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piha, S.; Pohjanheimo, T.; Lähteenmäki-Uutela, A.; Křečková, Z.; Otterbring, T. The effects of consumer knowledge on the willingness to buy insect food: An exploratory cross-regional study in Northern and Central Europe. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 70, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, S.; Sogari, G.; Menozzi, D.; Nuvoloni, R.; Torracca, B.; Moruzzo, R.; Paci, G. Factors predicting the intention of eating an insect-based product. Foods 2019, 8, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pambo, K.O.; Mbeche, R.M.; Okello, J.J.; Kinyuru, J.N. Modelling cognitive determinants of the intentions to consume foods from edible insects: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. In Proceedings of the Seventh European Conference on Sensory and Consumer Research, Dijon, France, 11–14 September 2016. No. 138-2016-2047. [Google Scholar]

- Bredahl, L.; Grunert, K.G. Determinants of the consumption of fish and shellfish in Denmark: An application of the theory of planned behavior. In International Seafood Conference: Seafood from Producer to Consumer, Integrated Approach to Quality; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke, W.; Vackier, I. Individual determinants of fish consumption: Application of the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite 2005, 44, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamberg, S.; Hunecke, M.; Blöbaum, A. Social context, personal norms and the use of public transportation: Two field studies. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G.; Bartels, J. The Norm Activation Model: An exploration of the functions of anticipated pride and guilt in pro-environmental behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 39, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Joireman, J.A.; Lasane, T.P.; Bennett, J.; Richards, D.; Solaimani, S. Integrating social value orientation and the consideration of future consequences within the extended norm activation model of proenvironmental behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, J.J.; Hwang, J. The environmentally friendly role of edible insect restaurants in the tourism industry: Applying an extended theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3581–3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.; Manstead, A.S.; Stradling, S.G. Extending the theory of planned behaviour: The role of personal norm. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 34, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priester, J.R.; Petty, R.E. The gradual threshold model of ambivalence: Relating the positive and negative bases of attitudes to subjective ambivalence. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.M.; Zanna, M.P.; Griffin, D.W. Let’s not be indifferent about (attitudinal) ambivalence. Attitude Strength Antecedents Conseq. 1995, 4, 361–386. [Google Scholar]

- Dagevos, H. Finding flexitarians: Current studies on meat eaters and meat reducers. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart Protein Project. What Consumers Want: A Survey on European Consumer Attitudes Towards Plant-Based Foods. Country Specific Insights; Report by Smart Protein Project compiled by ProVeg International; University of Copenhagen & Ghent University: København, Denmark; Ghent, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Agrifoodmonitor. 2021. Available online: https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/edepot/555097 (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Dagevos, H. Vegetarianism in the Dutch polder. In To Eat or Not to Eat Meat: How Vegetarian Dietary Choices Influence our Social Lives; De Backer, C.J., Fisher, M.L., Dare, J., Costello, L., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2019; pp. 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet, C.; Bouamra-Mechemache, Z.; Réquillart, V.; Treich, N. Regulating meat consumption to improve health, the environment and animal welfare. Food Policy 2020, 97, 101847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkman, G.; Walton, G.M. Dynamic norms promote sustainable behavior, even if it is counternormative. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 28, 1663–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolderdijk, J.W.; Jans, L. Minority influence in climate change mitigation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 42, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kincaid, D.L. From innovation to social norm: Bounded normative influence. J. Health Commun. 2004, 9 (Suppl. S1), 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M. Including context in consumer segmentation: A literature overview shows the what, why, and how. Methods Consum. Res. 2018, 1, 383–400. [Google Scholar]

- Verain, M.C.D.; Bartels, J.; Dagevos, H.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G. Segments of sustainable food consumers: A literature review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, L.; Umberger, W.J. Distinguishing meat reducers from unrestricted omnivores, vegetarians and vegans: A comprehensive comparison of Australian consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 88, 104081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, N.; Marquès, M.; Nadal, M.; Domingo, J.L. Meat consumption: Which are the current global risks? A review of recent (2010–2020) evidences. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.R.; Onwezen, M.C.; van der Meer, M. Consumer perceptions of different protein alternatives. In Meat and Meat Replacements; Woodhead Publishing: Thorston, UK, 2022; pp. 333–362. [Google Scholar]

- Kusch, S.; Fiebelkorn, F. Environmental impact judgments of meat, vegetarian, and insect burgers: Unifying the negative footprint illusion and quantity insensitivity. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 78, 103731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, F.; Knaapila, A.; Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. A multi-national comparison of meat eaters’ attitudes and expectations for burgers containing beef, pea or algae protein. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 91, 104195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, P. If you build it, will they eat it?: Consumer preferences for plant-based and cultured meat burgers. Appetite 2018, 125, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Schilo, L.; Grimm, K.J. Using residualized change versus difference scores for longitudinal research. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2018, 35, 32–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollwitzer, M.; Christ, O.; Lemmer, G. Individual differences make a difference: On the use and the psychometric properties of difference scores in social psychology. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 44, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzmaurice, G.; Davidian, M.; Verbeke, G.; Molenberghs, G. (Eds.) Longitudinal Data Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kisbu-Sakarya, Y.; MacKinnon, D.P.; Aiken, L.S. A Monte Carlo comparison study of the power of the analysis of covariance, simple difference, and residual change scores in testing two-wave data. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2013, 73, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. Consumer attitudes and behavior: The theory of planned behavior applied to food consumption decisions. Ital. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2015, 70, 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Han, T.I.; Stoel, L. Explaining socially responsible consumer behavior: A meta-analytic review of theory of planned behavior. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2017, 29, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, D.J.; Hogg, M.A.; White, K.M. The theory of planned behaviour: Self-identity, social identity and group norms. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 38, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herpen, E.; Pieters, R.; Zeelenberg, M. When demand accelerates demand: Trailing the bandwagon. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandstra, E.H.; Carvalho, Á.H.; Van Herpen, E. Effects of front-of-pack social norm messages on food choice and liking. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 58, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stok, F.M.; Hoffmann, S.; Volkert, D.; Boeing, H.; Ensenauer, R.; Stelmach-Mardas, M.; Kiesswetter, E.; Weber, A.; Rohm, H.; Lien, N.; et al. The DONE framework: Creation, evaluation, and updating of an interdisciplinary, dynamic framework 2.0 of determinants of nutrition and eating. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiselman, H.L. The role of context in food choice, food acceptance and food consumption. Front. Nutr. 2006, 3, 179. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, J.I.; Schuitema, G. How to make the unpopular popular? Policy characteristics, social norms and the acceptability of environmental policies. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 19, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Jacobson, R.P. Influences of social norms on climate change-related behaviors. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2021, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardikiotis, A. Minority influence. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2011, 5, 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O. Strong and weak principles for progressing from precontemplation to action on the basis of twelve problem behaviors. Health Psychol. 1994, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C. The application of systematic steps for interventions towards meat-reduced diets. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 119, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufik, D.; Bouwman, E.P.; Reinders, M.J.; Dagevos, H. A reversal of defaults: Implementing a menu-based default nudge to promote out-of-home consumer adoption of plant-based meat alternatives. Appetite 2022, 175, 106049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, S.; Reese, G.; Obersteiner, M. Modelling the drivers of a widespread shift to sustainable diets. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, G.W.; Scalco, A.; Craig, T.; Whybrow, S.; Macdiarmid, J.L. Social, temporal and situational influences on meat consumption in the UK population. Appetite 2019, 138, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacroix, K.; Gifford, R. Reducing meat consumption: Identifying group-specific inhibitors using latent profile analysis. Appetite 2019, 138, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hielkema, M.H.; Onwezen, M.C.; Reinders, M.J. Veg on the menu? Differences in menu design interventions to increase vegetarian food choice between meat-reducers and non-reducers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 102, 104675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Raaij, W.F.; Verhallen, T.M. Domain-specific market segmentation. Eur. J. Mark. 1994, 28, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Trijp, H.C.; Fischer, A.R. Mobilizing consumer demand for sustainable development. In The TransForum Model: Transforming Agro Innovation Toward Sustainable Development; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 73–96. [Google Scholar]

| Cross-Sectional Datasets | Longitudinal Dataset | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2019 | 2015 | 2019 | |

| α | α | α | α | |

| Social norms | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| Attitude | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| Perceived behavioral control | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.76 |

| Personal norm health | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.89 |

| Personal norm environment | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.90 |

| Ambivalence | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| Intention to buy | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 |

| Fish | Seaweed | Pulses | Insects | Cultured Meat | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2019 | 2015 | 2019 | 2015 | 2019 | 2015 | 2019 | 2015 | 2019 | |

| Social norms | 1.90 | 2.29 *** | 2.06 | 2.30 * | 1.98 | 2.45 *** | 1.69 | 1.96 ** | 2.43 | 2.99 ** |

| Attitude | 4.15 | 4.33 | 4.54 | 4.61 | 4.23 | 4.63 *** | 3.55 | 3.52 | 4.19 | 4.48 * |

| Perceived behavioral control | 4.70 | 4.70 | 4.04 | 4.17 | 4.08 | 4.41 ** | 3.50 | 3.71 * | 4.16 | 4.43 * |

| Personal norm health | 5.04 | 5.00 | 4.99 | 4.96 | 5.03 | 5.22 * | 4.99 | 4.98 | 5.06 | 5.07 |

| Personal norm environment | 4.86 | 4.95 | 4.87 | 4.98 | 4.94 | 5.07 | 4.89 | 5.03 | 4.93 | 5.02 |

| Ambivalence | 4.70 | 4.69 | 4.43 | 4.42 | 4.31 | 4.67 ** | 2.95 | 3.03 | 3.84 | 4.10 * |

| Intention | 1.99 | 2.31 * | 2.30 | 2.65 ** | 2.29 | 2.69 ** | 1.69 | 2.07 ** | 3.00 | 3.41 ** |

| Fish | Seaweed | Pulses | Insects | Cultured Meat | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Social norm | 0.62 *** | 19.47 | 0.60 *** | 19.13 | 0.58 *** | 17.83 | 0.58 *** | 16.69 | 0.39 *** | 11.59 |

| Attitude | 0.19 *** | 4.68 | 0.11 * | 2.43 | 0.25 *** | 5.05 | 0.09 * | 1.97 | 0.16 ** | 3.04 |

| PBC | 0.09 ** | 2.84 | 0.15 *** | 4.39 | 0.06 | 1.85 | 0.12 ** | 3.17 | 0.31 ** | 7.52 |

| PN health | −0.04 | −1.09 | 0.06 | 1.89 | 0.04 | 1.02 | 0.01 | 0.36 | 0.02 | 0.56 |

| PN environment | 0.05 | 1.57 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.99 | −0.02 | −0.45 | −0.05 | −1.35 |

| Ambivalence | 0.07 | 1.75 | 0.09 * | 1.99 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.10 * | 2.17 | 0.09 * | 2.08 |

| F = (df1, df2); R2 | F(6, 499) = 107.914 ***; R2 = 0.566 *** | F(6, 500) = 134.525 ***; R2 = 0.620 *** | F(6, 499) = 105.014 ***; R2 = 0.556 *** | F(6, 498) = 103.647 ***; R2 = 0.558 *** | F(6, 499) = 123.843 ***; R2 = 0.602 *** | |||||

| Fish | Seaweed | Pulses | Insects | In Vitro | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Social norm | 0.33 *** | 4.08 | 0.57 *** | 7.23 | 0.28 ** | 3.01 | 0.17 | 1.60 | 0.45 *** | 5.58 |

| Attitude | 0.30 ** | 3.01 | −0.14 | −1.43 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.22 * | 2.07 | 0.32 ** | 3.43 |

| PBC | 0.13 | 1.64 | 0.17 * | 2.23 | 0.17 | 1.68 | 0.24 * | 2.31 | 0.20 * | 2.43 |

| PN health | 0.02 | 0.26 | −0.02 | −0.17 | −0.12 | −1.09 | 0.17 | 1.54 | −0.10 | −1.12 |

| PN environment | 0.18 * | 2.19 | −0.08 | −0.93 | 0.09 | 0.88 | 0.12 | 1.03 | −0.09 | −0.98 |

| Ambivalence | 0.09 | 0.88 | 0.25 * | 2.62 | 0.22 | 1.81 | 0.09 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| F = (df1, df2); R2 | F(6, 106) = 10.574 ***; R2 = 0.388 *** | F(6, 106) = 17.154 ***; R2 = 0.507 *** | F(6, 101) = 5.164 ***; R2 = 0.246 *** | F(6, 81) = 6.602 ***; R2 = 0.346 *** | F(6, 99) = 20.002 ***; R2 = 0.567 *** | |||||

| Meat Lovers (n = 1230) | Flexitarians (n = 685) | Meat Abstainers (n = 73) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Social norm | 0.60 | 29.43 | 0.60 *** | 21.61 | 0.21 * | 2.27 |

| Attitude | 0.18 *** | 6.22 | 0.17 *** | 4.35 | 0.34 * | 2.57 |

| PBC | 0.11 *** | 4.98 | 0.14 *** | 4.68 | 0.32 ** | 3.26 |

| PN health | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.16 | 1.68 |

| PN environment | 0.00 | 0.22 | −0.03 | −1.02 | 0.02 | 0.24 |

| Ambivalence | 0.03 | 1.19 | 0.02 | 0.59 | 0.02 | 0.17 |

| Model 1 F = (df1, df2); R2 | F(6, 1223) = 278.613 ***; R2 = 578 *** | F(6, 678) = 156.068 ***; R2 = 0.576 *** | F(6, 66) = 18.786 ***; R2 = 0.631 *** | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Onwezen, M.C.; Verain, M.C.D.; Dagevos, H. Social Norms Support the Protein Transition: The Relevance of Social Norms to Explain Increased Acceptance of Alternative Protein Burgers over 5 Years. Foods 2022, 11, 3413. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11213413

Onwezen MC, Verain MCD, Dagevos H. Social Norms Support the Protein Transition: The Relevance of Social Norms to Explain Increased Acceptance of Alternative Protein Burgers over 5 Years. Foods. 2022; 11(21):3413. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11213413

Chicago/Turabian StyleOnwezen, Marleen C., Muriel C. D. Verain, and Hans Dagevos. 2022. "Social Norms Support the Protein Transition: The Relevance of Social Norms to Explain Increased Acceptance of Alternative Protein Burgers over 5 Years" Foods 11, no. 21: 3413. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11213413

APA StyleOnwezen, M. C., Verain, M. C. D., & Dagevos, H. (2022). Social Norms Support the Protein Transition: The Relevance of Social Norms to Explain Increased Acceptance of Alternative Protein Burgers over 5 Years. Foods, 11(21), 3413. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11213413