“Vegan Teachers Make Students Feel Really Bad”: Is Teaching Sustainable Nutrition Indoctrinating?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Teaching Sustainable Nutrition versus Risk of Indoctrinating

1.2. Aims of the Present Study

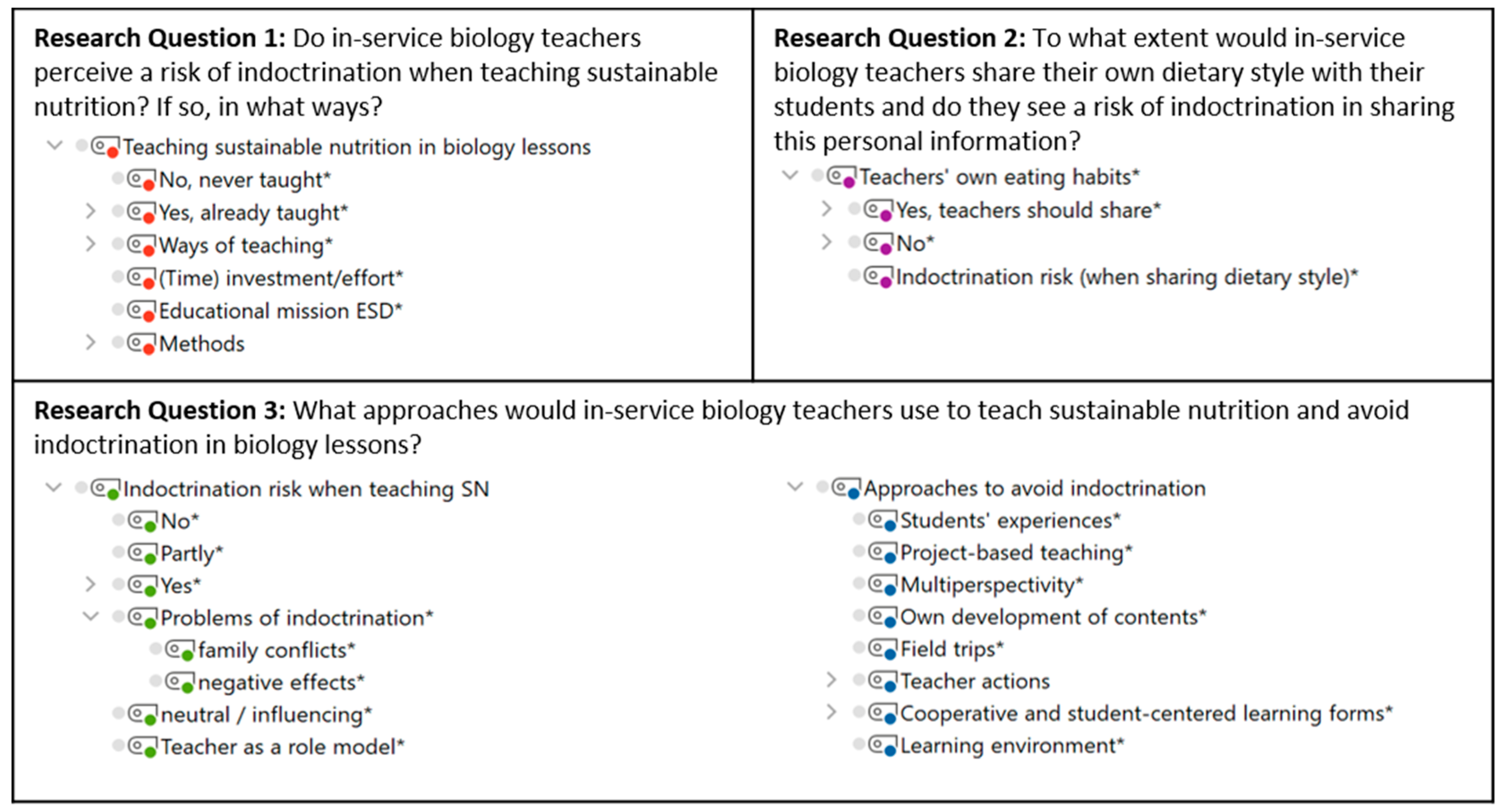

- Research Question 1: Do in-service biology teachers perceive a risk of indoctrination when teaching sustainable nutrition? If so, in what ways?

- Research Question 2: To what extent would in-service biology teachers share their own dietary style with their students, and do they see a risk of indoctrination in sharing this personal information?

- Research Question 3: What approaches would in-service biology teachers use to teach sustainable nutrition and avoid indoctrination in biology lessons?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Interview Procedure and Study Design

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

“[It is our mission as teachers] to educate with ESD in mind—[…] how we can deal with our future […] in order to shape it sustainably. And, in the end, an essential part is sustainable nutrition. […] Nutrition plays a major role in ESD, because it is something we can always do on our own as individuals.”(Mrs. Williams, 9)

3.1. Risk of Indoctrination When Teaching Sustainable Nutrition

“It depends a lot on how you deal with [sustainable nutrition] as a teacher. I think that indoctrination can be prevented by […] promoting the students’ ability to evaluate [certain contexts and situations]. […] That means that indoctrination can indeed take place through teachers, but I think that they are often aware of that risk and should pay attention to their pedagogical principles.”(Mr. Wood, 37)

“[Many] students do not have the ability to go shopping for themselves. […] There is, of course, a great risk that you could make the students look very bad through […] your teaching and your statements, and you could also give them a very bad conscience.”(Mr. Evans, 61)

“I think it is difficult when […] a teacher tries to live environmentally consciously and to eat as regionally and seasonally as possible or without meat. […] [As a vegan or vegetarian teacher] I think it is sometimes difficult […] to hold back [in the classroom] when it comes to animal husbandry or something like that. But I think it’s ok if you consciously decide to shed light on different perspectives and always integrate this [into your teaching].”(Mrs. Williams, 35)

“Over the years, […] [biology teachers] have been supplied with materials […] free of charge. For example, from the dairy industry or from agricultural interest groups. […] There is already filtered information. [The materials] do not show the whole range of a sustainable food economy and there are opportunities for indoctrination. […] But you don’t have to be subject to that. […] It is a question of the individual teacher to deal with it […] consciously and to say, ‘No I do not use the materials that way, I prepare them differently or I use my own materials.’”(Mr. Smith, 37)

“I think [whether you indoctrinate or not] always depends on the teacher, because you […] [automatically] serve as a role model for the younger students, especially in the fifth grade.”(Mrs. Robinson, 37)

“I think that somehow a teacher probably always influences students. […] Of course, it may be that I influence a student with my opinion, but that is not intentional […] and as long as you hold back, I think it is okay.”(Mrs. Williams, 39)

“As a teacher, I would be careful to present [sustainable nutrition] as objectively and neutrally as possible, […] just as in sex education […] or contraceptives, which is also similar, as this really affects the private sphere [of the students]. [Teachers] should […] respect the natural right of education of the parents and [be careful] that the parents do not feel attacked somehow.”(Mrs. Robinson, 37)

3.2. Revealing Teachers’ Own Dietary Style to Students

“If [the students] ask me, sure. If they don’t ask me, I wouldn’t say anything [about my own dietary style]. I would also explain why [I am vegetarian]; you are also a [role model for the students]. […] [As a teacher you] should build up a personal relationship [with your students]. Accordingly, [revealing the own dietary style to students] […] is completely legitimate in my eyes. It’s just like when you ask about political positions, you can also disclose them and explain them, and the student can still have a different opinion.”(Mr. Evans, 67)

“I personally would have no problem in sharing [my own dietary style to students], […] because for me it is also part of [teachers’] authenticity. But I can understand every teacher who doesn’t [reveal the own dietary style to students]. But then [the teachers] do not have to complain if it’s harder for the students to go their own way [in terms of a self-determined diet].”(Mr. Evans, 67)

“I am vegan and very convinced of my way of life. I really have to make sure that I remain objective and don’t dictate my opinion to the students.”(Mrs. Taylor, 53)

“I think [revealing my own dietary style to students] is a double-edged sword. Of course, as a teacher you are a role model in a certain way and if I […] tell the students that I consciously eat less meat for [different] reasons, and the other students all have their sausage as their lunch and then they say at the end ‘Oh, but Mrs. [Wilson] said that you are not really allowed to do that,’ then we are already back in the area of indoctrination, where I, of course, have a little more power of speech […] than the individual student. […] That would probably depend on the class in which you [reveal your own dietary style]. […] For example, if you stimulate a discussion about how […] [to] implement sustainable nutrition in our everyday lives, and […] the teacher is just one of many. But I would not stand there as […] a single example that has a normative character.”(Mrs. Wilson, 45)

3.3. Methodological Implementation of Sustainable Nutrition and Avoiding Indoctrination

“[It is important] that one chooses rather cooperative forms of teaching [sustainable nutrition]. Then, of course, one will again escape one’s own indoctrination tendency a little bit.”(Mrs. Wilson, 39)

“It must […] become clear to the students that you can’t just look at [sustainable nutrition] one-dimensionally [in the sense that we all have to eat sustainably]. Thus, looking at [sustainable nutrition] from different perspectives is important, because it is not always black and white. And we [as teachers] are required to illuminate different perspectives [for our students]. […] In the sense of good teaching, […] you [should] create diversity and then students should form their own opinion based on what we have worked out.”(Mrs. Williams, 27)

“I think it is very important that you […] [teach sustainable nutrition] with a large variety of methods, so that you don’t just give texts, but also look at videos and so on. So that you also see that it is all very diverse, and so that you look at the different perspectives. I would avoid doing exclusively frontal teaching, individual work or partner work. I think it is very important to […] interact with each other.”(Mrs. Williams, 27)

“One could […] have a debate at the end of a lesson [on sustainable nutrition]. [One of the following topics could be the basis for such a debate:] Should a veggie day be introduced in Germany? […] If you have such a debate, pro and contra arguments are elaborated and […] if the teacher chooses balanced teaching material, [the pro and contra arguments] […] have to be [roughly equally distributed]. […] [When pro and contra arguments are roughly equally distributed], […] it is given that there is no indoctrination. Because […] [the students and the teacher] capture [the topic of the debate] completely.”(Mrs. Williams, 27)

“I would first take a back seat as a teacher, so that the students can work it out for themselves with materials that are balanced and not one-sided. […] In the end, everyone is free to eat what he or she would like to eat. [The teacher should explicitly] point this out. There may be students who are already vegetarian. Teachers should also make sure that it is a well-mannered learning environment.”(Mrs. Williams, 27)

“[My] experience is that [teaching sustainable nutrition] is very time-consuming. […] There are a lot of organizational reasons that counteract […] [teaching sustainable nutrition]. But it is of course the case that you can also give students a lot to take with them on their way [to a more sustainable way of living].”(Mrs. Williams, 27)

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Question 1: Perceived Risk of Indoctrination When Teaching Sustainable Nutrition

4.2. Research Question 2: Revealing One’s Own Dietary Style to Students

4.3. Research Question 3: Approaches for Teaching Sustainable Nutrition and Avoiding Indoctrination

4.4. Limitations of the Study

5. Implications for Practice and Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Notarnicola, B.; Tassielli, G.; Renzulli, P.A.; Castellani, V.; Sala, S. Environmental impacts of food consumption in Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclaren, S.J. Sustainable diets: Eating within planetary boundaries. In New Zealand Land & Food Annual; Massey, C., Ed.; Massey University Press: Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2017; pp. 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- The EAT-Lancet Commission. Summary Report of the EAT-Lancet Commission: Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems—Food, Health, Planet; EAT: Oslo, Norway, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020: Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Healthy Diets; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; ISBN 9789251329016.

- Arias, P.A.; Bellouin, N.; Coppola, E.; Jones, R.G.; Krinner, G.; Marotzke, J.; Naik, V.; Palmer, M.D.; Plattner, G.-K.; Rogelj, J.; et al. Climate Change 2021. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zha, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Woolston, C. Healthy people, healthy planet: The search for a sustainable global diet. Nature 2020, 588, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renner, B.; Arens-Azevêdo, U.; Watzl, B.; Richter, M.; Virmani, K.; Linseisen, J. DGE position statement on a more sustainable diet. Ernährungs Umsch. 2021, 68, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- Eggert, S.; Barfod-Werner, I.; Bögeholz, S. Aufgaben zur Förderung der Bewertungskompetenz. In Biologie Methodik: Handbuch für die Sekundarstufe I und II; Spörhase, U., Ruppert, W., Eds.; Cornelsen: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 260–264. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche UNESCO-Kommission (DUK). Lehr- und Lernmaterialien zum Jahresthema Ernährung: UN-Dekade “Bildung für Nachhaltige Entwicklung”; DUK: Bonn, Germany, 2012; pp. 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann, D. Bildung für Nachhaltige Entwicklung in Schulen verankern; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017; ISBN 9783658169121. [Google Scholar]

- von Koerber, K.; Cartsburg, M. Potenziale der “Grundsätze für eine Nachhaltige Ernährung” zur Unterstützung der SDGs. In Ökologische Landwirtschaft und die UN-Ziele für Nachhaltige Entwicklung—Bio ist Teil der Lösung; de Schaetzen, S., Ed.; Nature & More: Waddinxveen, Netherlands, 2020; pp. 50–100. [Google Scholar]

- Rieckmann, M.; Holz, V. Verankerung von Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung in der Lehrerbildung. Z. Int. Bild. Entwickl. 2017, 3, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017; pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Blazar, D.; Kraft, M.A. Teacher and teaching effects on students’ attitudes and behaviors. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2017, 39, 146–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Büssing, A.G.; Schleper, M.; Menzel, S. Do pre-service teachers dance with wolves? Subject-specific teacher professional development in a recent biodiversity conservation issue. Sustainability 2018, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qablan, A.M.; Al-Ruz, J.A.; Khasawneh, S.; Al-Omari, A. Education for sustainable development: Liberation or indoctrination? An assessment of faculty members’ attitudes and classroom practices. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2009, 4, 401–417. [Google Scholar]

- Niedersächsisches Kultusministerium. Runderlass—Bildung für Nachhaltige Entwicklung (BNE) an Öffentlichen Allgemein Bildenden und Berufsbildenden Schulen Sowie Schulen in Freier Trägerschaft. 2021, pp. 1–6. Available online: https://www.mk.niedersachsen.de/download/166879/BNE-Erlass_Niedersachsen.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- KMK (Kultusministerkonferenz). Bildungsstandards im Fach Biologie für den Mittleren Schulabschluss; Sekretariat der Ständigen Konferenz der Kultusminister der Länder in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Bonn, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Niedersächsisches Kultusministerium. Kerncurriculum für das Gymnasium Schuljahrgänge 5–10: Naturwissenschaften—Biologie; Unidruck: Hannover, Germany, 2015; pp. 69–98. [Google Scholar]

- Fiebelkorn, F.; Kuckuck, M. Insekten oder In-vitro-Fleisch—Was ist nachhaltiger? Eine Beurteilung mithilfe der Methode des “Expliziten Bewertens.”. Prax. Geogr. 2019, 6, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberg, R. Values education as the daily fostering of school rules. Res. Educ. 2008, 80, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.; Fiebelkorn, F. Nachhaltige Ernährung, Naturverbundenheit und Umweltbetroffenheit von angehenden Biologielehrkräften—Eine Anwendung der Theorie des geplanten Verhaltens. Z. Didakt. Nat. 2019, 25, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.; Büssing, A.G.; Jarzyna, R.; Fiebelkorn, F. Do German student biology teachers intend to eat sustainably? Extending the theory of planned behavior with nature relatedness and environmental concern. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.; Hahn, S.C.; Fiebelkorn, F. Teach what you eat: Student biology teachers’ intention to teach sustainable nutrition. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 1018–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, M.M. How does professional development improve teaching? Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 945–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson, A. Indoctrination or education? Intention of unqualified teachers to transfer consumption norms in home economics teaching. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 682–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudenredaktion Indoktrination. Available online: https://www.duden.de/rechtschreibung/Indoktrination (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Arthur, J. Education with Character: The Moral Economy of Schooling; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 9780415277792. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, K.; Klein, M. Indoktrination. In Das Politiklexikon; Schubert, K., Klein, M., Eds.; Dietz: Bonn, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wehling, H.-G. Konsens à la Beutelsbach? Nachlese zu einem Expertengespräch. In Das Konsensproblem in der Politischen Bildung; Schiele, S., Schneider, H., Eds.; Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Mecklenburg-Vorpommern: Stuttgart, Germany, 1977; pp. 173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Däuble, H. Der fruchtbare Dissens um den Beutelsbacher Konsens. GWP-Ges. Wirtsch. Polit. 2016, 65, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiebelkorn, F.; Puchert, N.; Dossey, A.T. An exercise on data-based decision-making: Comparing the sustainability of meat and edible insects. Am. Biol. Teach. 2020, 82, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development; Leicht, A., Heiss, J., Byun, W.J., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018; ISBN 978-92-3-100244-1. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, F. Nachhaltige Ernährung im Kontext des Fleischkonsums im Biologieunterricht—Ein Spannungsfeld zwischen Authentizität und Indoktrination? Bachelor’s Thesis, Osnabrück University, Osnabrück, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Loose, K. Should Biology Teachers Practice What They Preach? Schülervorstellungen zur Authentizität und Indoktrination von Lehrkräften im Kontext “Nachhaltige Ernährung”. Master’s Thesis, Osnabrück University, Osnabrück, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- BigBlueButton Inc. BigBlueButton; Open Source Virtual Classroom Software; BigBlueButton Inc.: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Linkemeyer, L. Welche Vorstellungen haben angehende Biologielehrkräfte über “Nachhaltige Ernährung” und wie schätzen sie das Spannungsfeld zwischen dem Unterrichten von nachhaltiger Ernährung und einer möglichen Indoktrination ein? Bachelor’s Thesis, Osnabrück University, Osnabrück, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung, 4th ed.; Kuckartz, U., Ed.; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2018; ISBN 9783779936824. [Google Scholar]

- Dresing, T.; Pehl, T. Praxisbuch Interview, Transkription & Analyse. Anleitungen und Regelsysteme für Qualitativ Forschende, 8th ed.; dr dresing & pehl GmbH: Marburg, Germany, 2018; ISBN 9783818504892. [Google Scholar]

- VERBI Software MAXQDA; Software für Qualitative Datenanalyse; VERBI Software: Berlin, Germany, 2020.

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken; Beltz Verlag: Weinheim, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 9783407257307. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, R.L.; Prediger, D.J. Coefficient kappa: Some uses, misuses and alternatives. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1981, 41, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Jha, M. Values influencing sustainable consumption behaviour: Exploring the contextual relationship. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 76, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude-behavioral intention” gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornhoff-Grewe, M. Learning Prerequisites for Education for Sustainable Nutrition. Ph.D. Thesis, Osnabrück University, Osnabrück, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bellina, L.; Tegeler, M.K.; Müller-Christ, G.; Potthast, T. Bildung für Nachhaltige Entwicklung (BNE) in der Hochschullehre. In Nachhaltigkeit an Hochschulen: Entwickeln—Vernetzen—Berichten; Universität Bremen: Bremen, Germany; Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen: Tübingen, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–94. [Google Scholar]

- Höijer, K.; Hjälmeskog, K.; Fjellström, C. “Food with a purpose”—Home economics teachers’ construction of food and home. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzel, H. Fishbowl. In Biologie Methodik: Handbuch für die Sekundarstufe I und II; Spörhase, U., Ruppert, W., Eds.; Cornelsen: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 225–228. [Google Scholar]

- Kultusministerkonferenz (KMK). Bildungsstandards im Fach Biologie für die Allgemeine Hochschulreife; Kultusministerkonferenz (KMK), Ed.; Wolters Kluwe: Bonn, Germany; Berlin, Germany, 2020; ISBN 978-3-556-09043-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kemnitzer, K.; Damerau, K.; Wilde, M. Mehrperspektivität im Biologieunterricht. In Biologie Methodik: Handbuch für die Sekundarstufe I und II; Spörhase, U., Ruppert, W., Eds.; Cornelsen: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfgang, R.; Spörhase-Eichmann, U. Biologie-Didaktik: Praxishandbuch für die Sekundarstufe I und II; Spörhase-Eichmann, U., Ruppert, W., Eds.; Cornelsen: Berlin, Germany, 2004; ISBN 978-3589232048. [Google Scholar]

- Niebert, K.; Gropengießer, H. Leitfadengestützte Interviews. In Methoden in der Naturwissenschaftsdidaktischen Forschung; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 121–132. ISBN 978-3-642-37826-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Nature and operation of attitudes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Blake, J. Overcoming the “value-action gap” in environmental policy: Tensions between national policy and local experience. Int. J. Justice Sustain. 1999, 4, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Mr. Smith | Mrs. Robinson | Mrs. Williams | Mrs. Wilson | Mr. Evans | Mrs. Taylor | Mr. Wood |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | male | female | female | female | male | female | male |

| Age | 53 years | 44 years | 25 years | 27 years | 28 years | 33 years | 42 years |

| Teaching experience | 21 years | 20 years | 2 years | 1 year | 2 years | 7 years | 14 years |

| Diet | omnivorous | pescatarian | vegetarian | omnivorous | vegetarian | vegan | flexitarian |

| ESD in school 1 | + | + | ++ | + | + | ++ | ++ |

| SN in school 1 | + | ++ | + | + | + | ++ | + |

| 2nd/3rd subject | sports | German | sports | Latin | socialsciences | geography | geography/chemistry |

| School 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| Federal state 3 | LS | LS | NRW | LS | NRW | NRW | NRW |

| Teacher | Research Question 1 | Research Question 2 | Research Question 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of Indoctrination | Sharing Own Dietary Style with Students | Approaches to Teaching Sustainable Nutrition | |

| Mr. Smith | Yes; primarily due to learning materials; teachers are responsible for avoiding indoctrination | No, only fact-based and neutral, thus no risk of indoctrination | Project-based, primarily knowledge transfer |

| Mrs. Robinson | Yes; depending on teachers’ actions and beliefs; primarily due to teachers’ role model function—especially for younger students | Yes, as students are interested | Project-based, basic terms and concepts, field trips, multi-perspectivity |

| Mrs. Williams | Partly; depending on teachers’ actions and beliefs; withholding own opinions may be difficult for teachers—especially for environmentally conscious teachers | Only on students’ demand, no risk of indoctrination | Project-based, multi-perspectivity |

| Mrs. Wilson | Yes; depending on teachers’ actions and beliefs | Generally yes, but depending on the group of students; potential conflict between role model function and indoctrination | Evaluation competencies, project-based, discussions |

| Mr. Evans | Yes; depending on teachers’ actions; especially when teaching younger students | Only on students’ demand, but if students ask then of course, as it is part of an open and personal relationship with the students | Group work, multi-perspectivity |

| Mrs. Taylor | Yes; depending on teachers’ actions and beliefs; withholding own opinion may be difficult for teachers—especially when being vegan; experienced risk of indoctrination herself | Only on students’ demand; students are interested, potential risk of indoctrination, especially due to her own vegan dietary style | Multi-perspectivity |

| Mr. Wood | Generally yes; depending on teachers’ actions | Yes, as it is part of teachers’ authenticity; at risk of indoctrination | Multi-perspectivity, field trips, evaluation competencies, student-centered |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weber, A.; Linkemeyer, L.; Szczepanski, L.; Fiebelkorn, F. “Vegan Teachers Make Students Feel Really Bad”: Is Teaching Sustainable Nutrition Indoctrinating? Foods 2022, 11, 887. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11060887

Weber A, Linkemeyer L, Szczepanski L, Fiebelkorn F. “Vegan Teachers Make Students Feel Really Bad”: Is Teaching Sustainable Nutrition Indoctrinating? Foods. 2022; 11(6):887. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11060887

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeber, Alina, Laura Linkemeyer, Lena Szczepanski, and Florian Fiebelkorn. 2022. "“Vegan Teachers Make Students Feel Really Bad”: Is Teaching Sustainable Nutrition Indoctrinating?" Foods 11, no. 6: 887. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11060887

APA StyleWeber, A., Linkemeyer, L., Szczepanski, L., & Fiebelkorn, F. (2022). “Vegan Teachers Make Students Feel Really Bad”: Is Teaching Sustainable Nutrition Indoctrinating? Foods, 11(6), 887. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11060887