Consumer Behavior Concerning Meat Consumption: Evidence from Brazil

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire Development

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Content Analysis

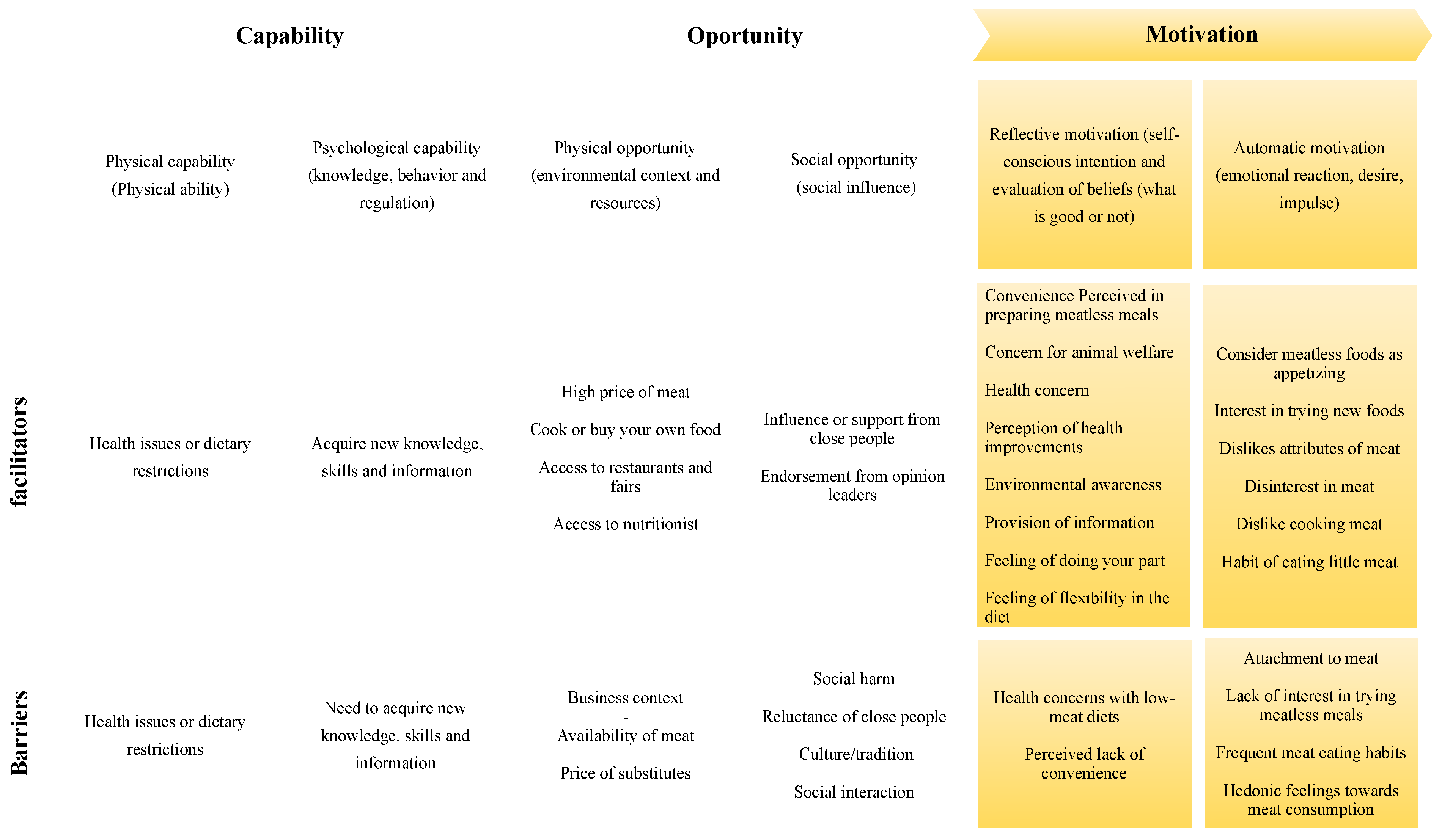

3. Results

3.1. Facilitators

3.1.1. Physical Capability

3.1.2. Psychological Capability

“I think what worked for me and helped me, and might help other people, is getting familiar with recipes. Who knows, on social media, social media profiles, YouTube channels that promote vegan and vegetarian recipes. Because there you can find recipes and you can make cool food that doesn’t have any meat in it, and I think that is what helped me most”.

“I went to a nutritionist, questioned him and asked things […] he then helped me a lot to understand how to put a menu together, replacing a certain spice and why it’s important to do that, and other kinds of food that have proteins similar to meat”.

3.1.3. Physical Opportunity

“meat these days is really, really expensive! So, whether you like it or not, a diet based on plants, on grains, ends up being a little bit… cheaper”.

“One really cool thing that I saw at my university is that, for instance, the canteen, the university restaurant there, has a vegetarian option that varies a lot every day of the week and is regulated by a nutritionist… So, having that option available at universities, in schools, makes it easier”.

“You know, I think the fruit and veg market helped me a lot. Doing the shopping there. I mean, I said to myself ‘today, I want to get this at the market… I want to get something that I don’t usually eat’, and then I’d get it”.

3.1.4. Social Opportunity

“I think that influence has something to do with it… I have friends who also do this with their food or meals, I mean, with less meat, and I think that this ended up making me a bit more of a vegetarian and vegan, so that helps as well”.

“I go rock climbing and the person that I think was the best climber at the time is a vegetarian. So, I started to look for high performance people who are vegetarians”.

3.1.5. Reflexive Motivation

“I feel like doing more exercise, I feel better eating less meat, and I feel healthier in general. So, it’s good for… for everything, for your self-esteem, for… I feel less tired and I digest food more quickly”.

“I began to rethink my diet a lot, not only regarding meat but also things that I eat that don’t have any meat in them. Mainly cutting out, reducing, eliminating ready-made processed food, things that have a lot of processed spices and a lot of preservatives in them, a lot of artificial flavoring. So, I cut down on these things a lot and as a result I also cut down on my meat consumption”.

“I learned quite a few things through courses, documentaries, and classes at university that made me see that I wanted to reduce [meat] consumption in my diet”.

3.1.6. Automatic Motivation

“I think I started experimenting more, you know? So, every now and then I go to order food on iFood, then I like to order different things that I think I might like, you know? So, instead of ordering the usual, I take more risks, because I’m trying to identify new kinds of food, right?”

3.2. Barriers

3.2.1. Physical Capability

“I find it hard to digest grains, no matter how I cook them I just can’t”. Thus, “no matter how much people want to make this change in their eating habits, some health issue prevents it”.(Carolina, age 19)

3.2.2. Psychological Capability

“I think it’s about a lack of information on how to keep the same nutrients because a lot of people think ‘ah, protein is only found in meat’. So, there is a lack of information on how you can keep the same level of proteins but with a different diet”.

3.2.3. Physical Opportunity

3.2.4. Social Opportunity

“There are only the two of us at home. Am I going to make food and force him to do without meat when he wants to eat it? I end up eating it with him”. Another barrier identified in the interviews is related to the culture and tradition of meat consumption. After all, it is a central component of the meals of many Brazilians, and the social norm determines the consumption of meat as a standard. Leonardo, 21, for example, said that “It’s already kind of established in society that we need to eat meat and eat it in large quantities since childhood”. He thinks that “this could be a latent difficulty”. Other consumers also commented on the barbecue culture: “you see it in commercials, you see it in Brazilian culture, people having barbecues and all that”.(Ricardo, age 27)

“Sometimes there was an event at the company when I was still working and I had to go, I had to go because everyone went and there was only meat, there was nothing that a vegetarian could eat […]. And when you didn’t eat anything, you still felt bad, because people sometimes either made a joke or didn’t say anything, but they thought you were… you know? It’s a bit of a bad feeling like that, on both sides. People are not prepared to deal with it and so are you sometimes… you don’t want to go through this, so sometimes you prefer to avoid this situation […]. I don’t go to that kind of event anymore. Especially if it’s a barbecue, for example”.

“She thinks it’s ridiculous to eat less meat or cut out meat altogether. So, this year, the meat I’ve consumed wasn’t bought by me. I haven’t bought any meat this year. It was all meat that my mother bought”.

3.2.5. Reflexive Motivation

3.2.6. Automatic Motivation

“Baloney was something we ate a lot of when we were kids, because it was cheap. So, I eat this stuff from time to time, but I eat it with a guilty conscience, knowing that I’m eating something that’s not good for me, you know? But for the taste itself, just to satisfy that urge. Maybe I’ll be on my deathbed and I’ll be like, ‘Oh, I want to eat a sandwich’ just because I miss that sandwich, you know?”.

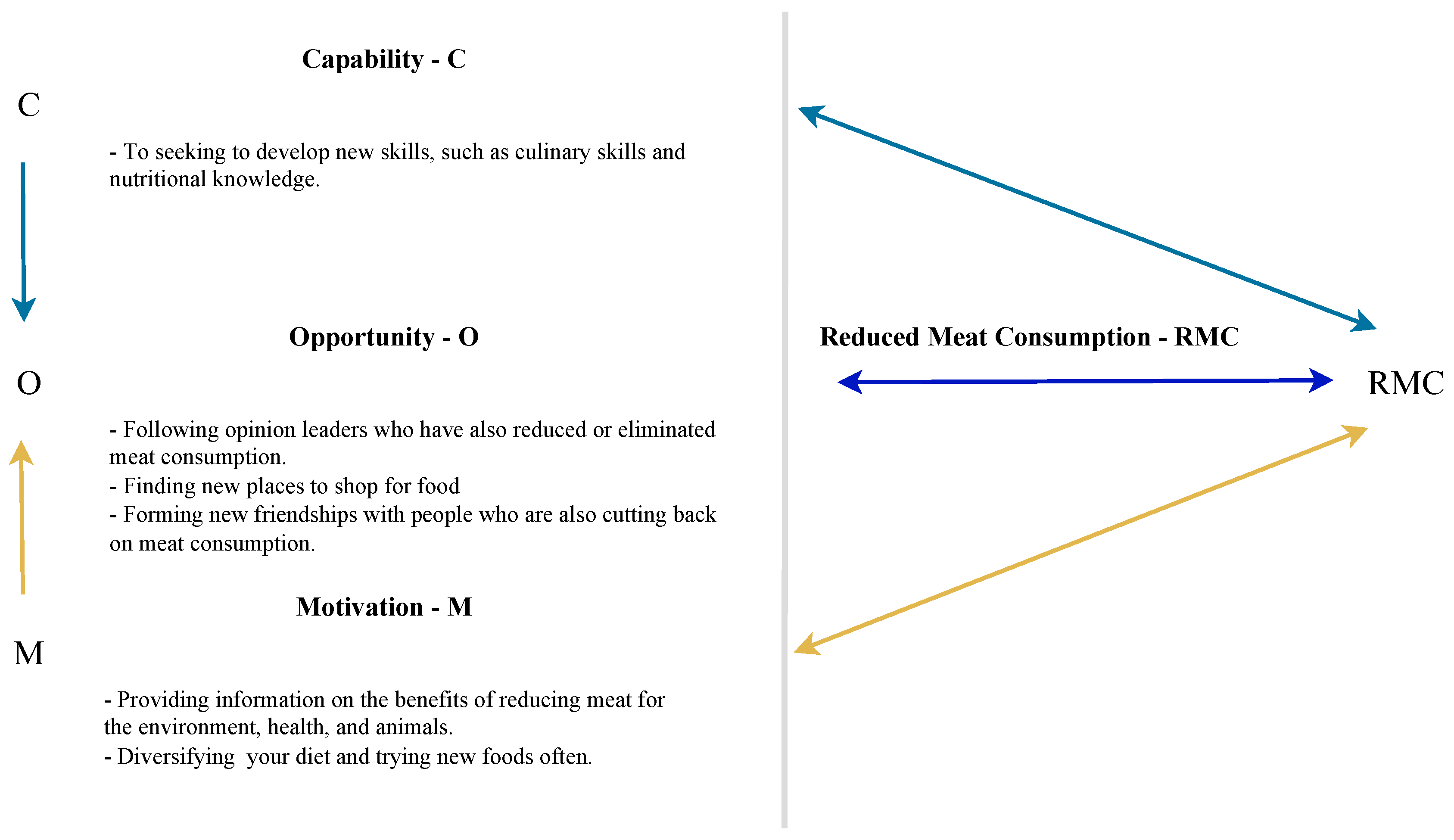

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Managerial Contributions

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Majeed, O.H.; Farhan, M.N.; Salloum, T.M. The Impact of Dumping Policy on the Food Gap of Chicken Meat in Iraq For the Period (2004–2019)—Turkish Imports Of Chicken Meat a Case Study. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2022, 7, e0575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, I.; Lindblom, C.; Åbacka, G.; Bengs, C.; Hörnell, A. “He just has to like ham”—The centrality of meat in home and consumer studies. Appetite 2015, 95, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemper, J.A. Motivations, barriers, and strategies for meat reduction at different family lifecycle stages. Appetite 2020, 150, 104644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinfeld, H.; Gerber, P.; Wassenaar, T.; Castel, V.; Rosales, M.; de Haan, C. Livestock’s Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a0701e/a0701e00.htm (accessed on 23 July 2021).

- Grandin, T. Animal welfare and society concerns finding the missing link. Meat Sci. 2014, 98, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirbiš, A.; Lamot, M.; Javornik, M. The Role of Education in Sustainable Dietary Patterns in Slovenia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gere, A.; Harizi, A.; Bellissimo, N.; Roberts, D.; Moskowitz, H. Creating a Mind Genomics Wiki for Non-Meat Analogs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, J.; Calheiros, M.M.; Oliveira, A. Moral Disengagement in Harmful but Cherished Food Practices? An Exploration into the Case of Meat. J. Agric. Environ. Ethic. 2014, 27, 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo-Vélez, G.; Tybur, J.M.; van Vugt, M. Unsustainable, unhealthy, or disgusting? Comparing different persuasive messages against meat consumption. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 58, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einhorn, L. Meat consumption, classed? The socioeconomic underpinnings of dietary change. Osterr. Z. Für Soziologie 2021, 46, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, M.N.B.; da Veiga, C.P.; da Veiga, C.R.P.; Reis, G.G.; Pascuci, L.M. Reducing meat consumption: Insights from a bibliometric analysis and future scopes. Futur. Foods 2022, 5, 100120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, F.; Heuer, T.; Krems, C.; Claupein, E. Meat consumers and non-meat consumers in Germany: A characterisation based on results of the German National Nutrition Survey II. J. Nutr. Sci. 2019, 8, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tobler, C.; Visschers, V.H.; Siegrist, M. Eating green. Consumers’ willingness to adopt ecological food consumption behaviors. Appetite 2011, 57, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zur, I.; Klöckner, C.A. Individual motivations for limiting meat consumption. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagevos, H. Finding flexitarians: Current studies on meat eaters and meat reducers. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagevos, H.; Voordouw, J. Sustainability and meat consumption: Is reduction realistic? Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2013, 9, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gavelle, E.; Davidenko, O.; Fouillet, H.; Delarue, J.; Darcel, N.; Huneau, J.-F.; Mariotti, F. Self-declared attitudes and beliefs regarding protein sources are a good prediction of the degree of transition to a low-meat diet in France. Appetite 2019, 142, 104345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagevos, H.; Verbeke, W. Meat consumption and flexitarianism in the Low Countries. Meat Sci. 2022, 192, 108894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malek, L.; Umberger, W.J.; Goddard, E. Committed vs. uncommitted meat eaters: Understanding willingness to change protein consumption. Appetite 2019, 138, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.A. The significance of sensory appeal for reduced meat consumption. Appetite 2014, 81, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C.; Van Nek, L.; Rolland, N.C.M. European Markets for Cultured Meat: A Comparison of Germany and France. Foods 2020, 9, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borusiak, B.; Szymkowiak, A.; Kucharska, B.; Gálová, J.; Mravcová, A. Predictors of intention to reduce meat consumption due to environmental reasons—Results from Poland and Slovakia. Meat Sci. 2021, 184, 108674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Meat Consumption (Indicator); Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Graça, J.; Godinho, C.A.; Truninger, M. Reducing meat consumption and following plant-based diets: Current evidence and future directions to inform integrated transitions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collier, E.S.; Oberrauter, L.-M.; Normann, A.; Norman, C.; Svensson, M.; Niimi, J.; Bergman, P. Identifying barriers to decreasing meat consumption and increasing acceptance of meat substitutes among Swedish consumers. Appetite 2021, 167, 105643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khara, T.; Riedy, C.; Ruby, M.B. A cross cultural meat paradox: A qualitative study of Australia and India. Appetite 2021, 164, 105227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijtsema, S.J.; Dagevos, H.; Nassar, G.; van Haaster de Winter, M.; Snoek, H.M. Capabilities and Opportunities of Flexitarians to Become Food Innovators for a Healthy Planet: Two Explorative Studies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.K.; Ballantine, P.W.; Ozanne, L.K. Consumer adoption of plant-based meat substitutes: A network of social practices. Appetite 2022, 175, 106037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hötzel, M.J.; Vandresen, B. Brazilians’ attitudes to meat consumption and production: Present and future challenges to the sustainability of the meat industry. Meat Sci. 2022, 192, 108893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, R.A.; Edwards, D.; Palmer, A.; Ramsing, R.; Righter, A.; Wolfson, J. Reducing meat consumption in the USA: A nationally representative survey of attitudes and behaviours. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1835–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taufik, D. Prospective “warm-glow” of reducing meat consumption in China: Emotional associations with intentions for meat consumption curtailment and consumption of meat substitutes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 60, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordts, A.; Nitzko, S.; Spiller, A. Consumer response to negative information on meat consumption in Germany. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 83–106. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84920688499&partnerID=40&md5=e42ff1d985e5af48f5c3f72daab1d223 (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Stoll-Kleemann, S.; Schmidt, U.J. Reducing meat consumption in developed and transition countries to counter climate change and biodiversity loss: A review of influence factors. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2016, 17, 1261–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jalil, A.J.; Tasoff, J.; Bustamante, A.V. Eating to save the planet: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial using individual-level food purchase data. Food Policy 2020, 95, 101950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; van der Weele, C.N. When indifference is ambivalence: Strategic ignorance about meat consumption. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 52, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutkowska, K.; Czarnecki, J.; Głąbska, D.; Guzek, D.; Batóg, A. Consumer perception of health properties and of other attributes of beef as determinants of consumption and purchase decisions. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2018, 69, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austgulen, M.H.; Skuland, S.E.; Schjøll, A.; Alfnes, F. Consumer Readiness to Reduce Meat Consumption for the Purpose of Environmental Sustainability: Insights from Norway. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SVB—Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira. Available online: https://www.svb.org.br/pages/segundasemcarne/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Weinrich, R. Cross-Cultural Comparison between German, French and Dutch Consumer Preferences for Meat Substitutes. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michel, F.; Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Consumers’ associations, perceptions and acceptance of meat and plant-based meat alternatives. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 87, 104063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, J.; Calheiros, M.M.; Oliveira, A. Attached to meat? (Un)Willingness and intentions to adopt a more plant-based diet. Appetite 2015, 95, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, J.; Oliveira, A.; Calheiros, M.M. Meat, beyond the plate. Data-driven hypotheses for understanding consumer willingness to adopt a more plant-based diet. Appetite 2015, 90, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, M.N.B.; da Veiga, C.R.P.; Su, Z.; Reis, G.G.; Pascuci, L.M.; da Veiga, C.P. Social Media Analysis to Understand the Expected Benefits by Plant-Based Meat Alternatives Consumers. Foods 2021, 10, 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Veiga, C.P.d.; Moreira, M.N.B.; Veiga, C.R.P.d.; Souza, A.; Su, Z. Consumer Behavior Concerning Meat Consumption: Evidence from Brazil. Foods 2023, 12, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12010188

Veiga CPd, Moreira MNB, Veiga CRPd, Souza A, Su Z. Consumer Behavior Concerning Meat Consumption: Evidence from Brazil. Foods. 2023; 12(1):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12010188

Chicago/Turabian StyleVeiga, Claudimar Pereira da, Mirian Natali Blézins Moreira, Cássia Rita Pereira da Veiga, Alceu Souza, and Zhaohui Su. 2023. "Consumer Behavior Concerning Meat Consumption: Evidence from Brazil" Foods 12, no. 1: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12010188

APA StyleVeiga, C. P. d., Moreira, M. N. B., Veiga, C. R. P. d., Souza, A., & Su, Z. (2023). Consumer Behavior Concerning Meat Consumption: Evidence from Brazil. Foods, 12(1), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12010188